Measuring Law Enforcement Suicide: Challenges and Opportunities: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 3 Additional Data Sources for Measuring Suicide

3

Additional Data Sources for Measuring Suicide

In addition to the primary data sources that measure suicide or law enforcement suicide specifically, many other sources of data measure suicidal behaviors—suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicides—and their correlates through secondary data analysis. These sources of data are discussed in this chapter, following an introduction to the data pipeline developed for this workshop. The chapter closes with lessons learned from the military that can help inform measurement of suicidal behaviors and identify risk and protective factors, using studies from the Army.

DATA PIPELINE

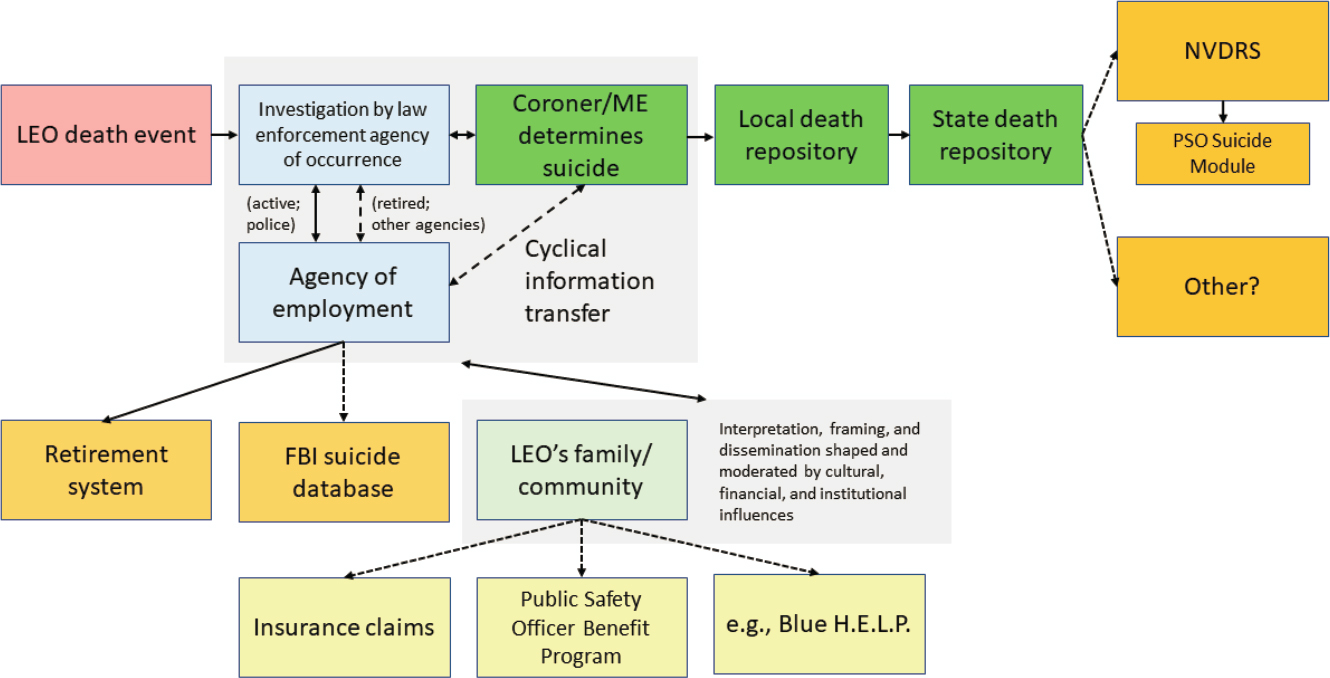

Planning committee member Brandon del Pozo (Brown University) presented original work on a model data pipeline to measure law enforcement suicide (Figure 3-1). Most of these data reside in the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) and now its new Public Safety Officer Suicide module. del Pozo described this model as an ecosystem, with many places where information (e.g., demographics, circumstances) about a deceased law enforcement officer will be funneled or extracted. The pipeline also identifies where bias and error can be introduced, a topic discussed in greater depth in Chapter 4.

The event that triggers inquiry into whether a law enforcement officer suicide occurred begins with the death event, followed by an investigation by the jurisdiction of the law enforcement agency where the death occurred. If it is in a different jurisdiction from where the decedent was employed or retired, the investigating agency will also serve as a source of information.

NOTES: FBI = Federal Bureau of Investigation; LEO = law enforcement officer; ME = medical examiner; NVDRS = National Violent Death Reporting System; PSO = public safety officer.

SOURCE: Taken from Brandon del Pozo presentation, April 26, 2023.

Ultimately, a coroner or medical examiner decides whether the death was a suicide. These data are collected at the local level and aggregated to the state repository level, after which they are reported and funneled into the NVDRS, ideally. An additional pathway now exists whereby information from the death investigation is also reported to the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI’s) Law Enforcement Suicide Data Collection. A law enforcement agency’s retirement system is another path where data flows as a matter of auditing to know whether the deceased officer’s benefits are legitimately going to survivor beneficiaries.

Other sources of information include the law enforcement officer’s family, friends, coworkers, and community. del Pozo questioned how data from these sources—often people who know whether the death was a suicide (but who may not want it to be regarded as a suicide because of stigma)—can be captured in data sets. Other sources that can provide more insight, del Pozo said, are insurance claims; the Public Safety Officer Benefits (PSOB) program; and nongovernmental organizations, such as Blue H.E.L.P.1 He concluded by acknowledging that this schema is far from complete; however, it can provide a framework for where data currently reside.

ADDITIONAL STUDIES

Planning committee member Jennifer Rineer (RTI International) provided an overview of additional data sources on suicide by stating that this discussion would focus on the key characteristics to consider in other data sources, highlight the breadth of relevant data sources and collections, identify differences between these data sets, and discuss the potential for these data sources to improve measurement of law enforcement suicide. Appendix C provides a snapshot of some of the data sets, highlighting how much information exists. Rineer outlined questions to consider when using other data sources:

- Who is the organization or funder?

- Are the data specific to law enforcement?

- Are occupational codes or categories captured and which types?

- What is the scope, sample size, and coverage?

- What is the data collection mechanism and process?

- In what year did the data collection begin (i.e., how many years of data are available)?

- What is the cadence of the data collection?

___________________

1 According to its website, Blue H.E.L.P. (“Honor. Educate. Lead. Prevent.”) honors the service of law enforcement officers who died by suicide (see https://bluehelp.org; see also the section on Nongovernmental Sources below).

- What types of measures are included: completed suicides, suicide attempts, predictors, correlates?

Relevant National Survey Data

Kathy Batts (RTI International) discussed other sources of existing national survey data that include a collective measure of suicidality with subcategories of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), Batts explained, is an annual survey conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration that collects information about substance use and misuse, as well as mental health indicators that include suicidality. For respondents age 18 or older, the NSDUH interview includes specific questions about suicidal ideation, having made a suicide plan, and/or suicide attempts within a past 12-month reference period. Secondly, Batts discussed the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), sponsored by most divisions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as well as other federal agencies. BRFSS is a system of telephone surveys conducted at the state level that reports data at state and local levels. The BRFSS includes a set of optional modules; Batts stated that 2010 was the most recent year for which she could find suicidality measures in BRFSS, and those were limited to a single question about suicide attempts that was asked in five states of respondents who were active servicemembers and veterans. Thirdly, Batts discussed the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), designed by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The NESARC last fielded questions on measuring lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in 2012 and 2013, in a module about major depressive disorder. Batts contends that NSDUH is the only data collection currently measuring suicidality of adults in the United States, although all three data sources can be used to develop better measures of law enforcement suicide.

When self-report information can be collected, Batts explained, it is preferable to use structured questions, which are less likely to be impacted by bias from the interviewer’s beliefs or understanding of the respondent’s experience. The questions in NSDUH, BRFSS, and NESARC have already been studied extensively—using cognitive testing, reliability, and validity—to measure constructs such as suicide attempts. While these questions may need additional testing to apply to the law enforcement population, they would be an excellent starting point for a new data collection. Batts cautioned that it is important for researchers to be mindful of the burden associated with any data collection. She noted that respondents may quickly learn that positive responses to screening questions may result in additional questions, which can lead to response attrition.

A final consideration for surveys is what level of confidentiality and privacy is necessary to support cooperation with a data collection about suicidality, which applies to both individuals and institutions. Batts conveyed that a limitation of using survey data is that not every respondent is cognitively capable of responding to a questionnaire, given the complexity of some of the constructs being measured. Other informants—surviving spouses, friends, coworkers—may also have limitations in the information they can provide because they may not know or be motivated to provide such information.

Nonsurvey Data Sources

Batts also described nonsurvey data sources that can provide contextual information about death by suicide. The CDC maintains the Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System, which includes the NVDRS (see Chapter 2). Another source is the National Death Index (NDI), which is a national-level data set maintained by the National Center for Health Statistics that uses death certificate records, as mentioned by Christopher Jones (CDC). Batts explained that the NDI data have been linked with data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and the National Health Interview Survey. Batts asserted that NDI linkages can serve as a model for integrating survey data with other data, because a linked file can provide information about context, limitations, and biases present when measuring suicidality. Similarly, survey participation could be incentivized by providing resources to participants or participating institutions that are specific to suicide prevention and response.

Nongovernmental Sources

One example of nongovernmental sources that collect information about law enforcement suicide is Blue H.E.L.P. (“Honor. Educate. Lead. Prevent.”), which also provides support to families. Blue H.E.L.P. is a component of a larger nonprofit called First H.E.L.P. Karen Solomon (Blue H.E.L.P.) cofounded this organization, which, on January 1, 2016, began to provide information about law enforcement suicide year-over-year in an effort to raise public awareness. While First H.E.L.P. collects data for all first responders, Solomon’s presentation was limited to law enforcement.

Blue H.E.L.P. gathers data from multiple sources (see Table 3-1), which improves understanding of what is known about the suicide. The types of data collected include demographics, relationship issues, and traumatic brain injury or concussion (recently added). Qualitative data are also provided through narratives.

TABLE 3-1 Data Collected by Blue H.E.L.P.

| Sources | Typesa |

|---|---|

| Departmentsb | Demographic information |

| Other LE organizations | On/off duty |

| Family and friends | Under investigation at time of death |

| Peer-support networks | Abnormal work issues |

| Internet searches | Recent loss of a LE career |

| Alcoholism and/or drug addiction | |

| Prior suicide attempt | |

| Childhood trauma | |

| Depression, diagnosed mental illness, and/or PTSD | |

| Recent loss of a loved one | |

| Relationship issues or domestic violence | |

| Financial issues | |

| Medical issues (work and nonwork related) | |

| TBI or concussion |

aNarratives are also collected.

bCoworkers, chiefs, etc.

NOTES: LE = law enforcement; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; TBI = traumatic brain injury.

SOURCE: Taken from Karen Solomon presentation, April 26, 2023.

Solomon stated that while Blue H.E.L.P. currently does not conduct psychological autopsies, greater than 50 percent of their families indicated in a poll that they would be willing to participate in this method. Because Blue H.E.L.P. is run by volunteers, its primary challenge with data collection is monetary. Solomon emphasized that the law enforcement population is different because “there is a culture and stigma against seeking help, having their gun removed, and the fear of their losing job.”

Investigator-Led Studies

Researchers (i.e., investigators) conduct targeted studies through grants or other funding mechanisms often published in peer-reviewed journals. Planning committee member Natasha Frost (Northeastern University) observed that most studies in the literature use surveillance data, are focused on policing, and are limited to suicidal ideation. Studies that examine completed suicides use different methodologies and often combine data sources. Methods for studying police suicide include retrospective cohorts, web surveillance, case studies, and systematic reviews (Chae & Boyle, 2013; Stanley et al., 2016; Violanti et al., 2019).

These studies can provide unique insights that large surveillance studies cannot, such as comparisons of active officers with those who are retired

or whose employment was terminated, and they highlight the potential for misclassification of suicide. It is also important to recognize the limitation of mortality surveillance databases that lack comparisons. Echoing a comment by Anthony Arita (Department of Homeland Security [DHS]) earlier in the workshop, Frost said, “It is important to consider the peers of those law enforcement officers who do not die by suicide. To sample those peers, health behaviors, and risk factors we need to study culture, stigma, and distrust as things we can address in the community.”

Frost is currently conducting a longitudinal study of correctional officer cohorts, following them for 4 years starting with their academy training, with funding from the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) for the first five years of the study. In another NIJ-funded study, Frost found that a random sample of corrections officers had more mental health symptoms than were found among a random sample of new recruits (Frost & Monteiro, 2020). As a result of this finding, the current longitudinal study uses in-person interviews every 12–18 months to collect data on various stressors—occupational, operational, organizational, workplace culture, bullying, perceived danger, violence exposure, suicides in the institution, and critical incidents. Additional data are collected on behavioral and psychological outcomes, such as alcohol use and insomnia, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and suicidality. Officers in the study have also consented to the researchers studying their personnel data, which includes demographics, work history, preemployment psychological testing, academy performance, job performance, and absenteeism. Administrative data include incident reports, grievances, and facility-level characteristics. Describing the strength of these investigator-led studies, Frost stated, “Although they cannot match the scale of data in the surveillance studies from the CDC, DHS, and FBI, they can provide a depth of data that are not present in the national data collection efforts. They can also serve to remind us that behind every suicide is a family and a community.”

DISCUSSION OF ADDITIONAL DATA SOURCES

In response to a discussion on compassion fatigue, Solomon stated that not all law enforcement officers will have compassion fatigue or suffer from PTSD. This results in a limitation for families, she continued, because “the PSOB Act is written narrowly, and one must prove the suicide was tied to the job due to a ‘harrowing incident or multi-casualty event.’ As these claims come in, and some are denied, we will have a better understanding of moral injury.” Batts noted that suicidal behavior is not homogeneous, and different pathways lead to suicide. She cited sleep patterns, mentioning that lack of sleep lowers impulse control, which could explain why some officers attempt a suicide on a given day.

In response to Batts’ presentation on BRFSS, Hope Tiesman (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [NIOSH]) shared that, since 2013, NIOSH has sponsored an optional module of BRFSS that pertains to industry and occupation injury, which uses Standard Occupational Classification codes in a computerized program. Thus, BRFSS is a promising data set with strong industry and occupational data for studying correlates of nonfatal suicidal outcomes.

Arita asked what else should be measured. Rineer responded that, as a workplace mental health researcher, she is curious about what types of services are being offered by employers and which are being accessed by employees? Similarly, Frost added that she is interested in what types of services officers would use. For example, peer counseling has not been found to be effective for serious mental health issues.

Planning committee member John Violanti (University at Buffalo) stressed the need for evaluation of suicide prevention in police work and offered an example that worked in Montreal. He also described an example from the Air Force, arguing that the community—airmen, commanders, chaplains, families—should be involved in prevention efforts and trained to recognize signs of suicide. An evaluation of this Air Force approach found that the rate of suicide dropped significantly.

LESSONS LEARNED FROM MILITARY DATA SOURCES

The military and law enforcement professions share many similarities in their populations. Law enforcement officers often have prior or concurrent (i.e., Reserves) military service; there is a strong nexus of service and duty to protect others; and both are male-dominated workforces. Despite this overlap, the military does not have the same level of heterogeneity in the number and size of their units as is present in law enforcement (a point highlighted in Chapter 2 by Jeffrey L. Sedgwick [Justice Research and Statistics Association]). While Servicemembers’ job duties may vary, the military is a closed system in which unique identifiers about a person can be easily linked to an array of administrative records and many will receive care with military or Veteran benefits, including the Veterans Health Administration. Measurement of law enforcement suicide will need to surmount barriers in access to data that are not present in the military; however, many lessons can be gleaned from what the military has learned about measuring suicidality in its population, especially about correlates.

Robert Ursano (Uniformed Services University) discussed several studies funded by the National Institute of Mental Health in 2006 and later by the

Department of Defense (DOD), that he and his colleagues2 designed and conducted: the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS)—including the longitudinal study (Army STARRS-LS). Ursano explained that the Army needed research that was sufficiently large, given that suicide is a rare event; creative, using state-of-the-art methodologies; and comprehensive, attacking the problem from multiple angles. These studies include eight component studies with several types of data—occupation, service history, promotion and demotion, health conditions, arrest history, family, violence, and surveys—as well as biospecimens. The aims of the Army STARRS-LS were to:

- identify risk and protective factors for suicide and suicide-related behavior for the Army to use for revising existing risk-reduction programs and efforts, and/or developing new risk-reduction programs;

- deliver actionable findings to the Army rapidly (i.e., during the course of the research, not waiting until the end); and

- establish Army cohorts for future follow-up studies and continued benefit to the Army and DOD.

Ursano noted that a unique feature of these studies was that the military health system has nearly total capture of health events and many life changes and stressors. This enables access to continuous health records, including inpatient or outpatient mental health treatment. For example, the Army STARRS Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS) component compiles these large data sets. There is also a New Soldier Study (NSS) that begins on the first day of Army entry. In this study, new soldiers complete a standardized survey and are asked for permission to link their administrative data, which becomes deidentified.

Case control designs were also used to compare specific Army soldier cohorts. The Soldier Health Outcome Study (SHOS) had two components: SHOS-A collected data on suicide attempts; SHOS-B collected data on completed suicides. SHOS-B was essentially a psychological autopsy for completed suicides and a matched control sample, but with important differences. Army supervisors and next of kin of soldiers who completed suicide or had demonstrated risk for suicide were interviewed. This resulted in 603 interviews for 150 cases (Army) and 276 controls (non-Army).

Ursano underscored that predictive analytics is a valuable new tool for identifying who is at risk and what interventions will be right for each person. Big data enable this analysis across a wide range of issues. The Army STARRS uses DOD’s Military Occupational Specialty codes to examine risk by occupation. In an analysis using these occupational codes,

___________________

2 Coauthors are Steve Heeringa, Ronald C. Kessler, Murray B. Stein, and James Wagener.

suicide attempts were noted among combat medics, with the highest number of attempts peaking at about 6 months after entering service.

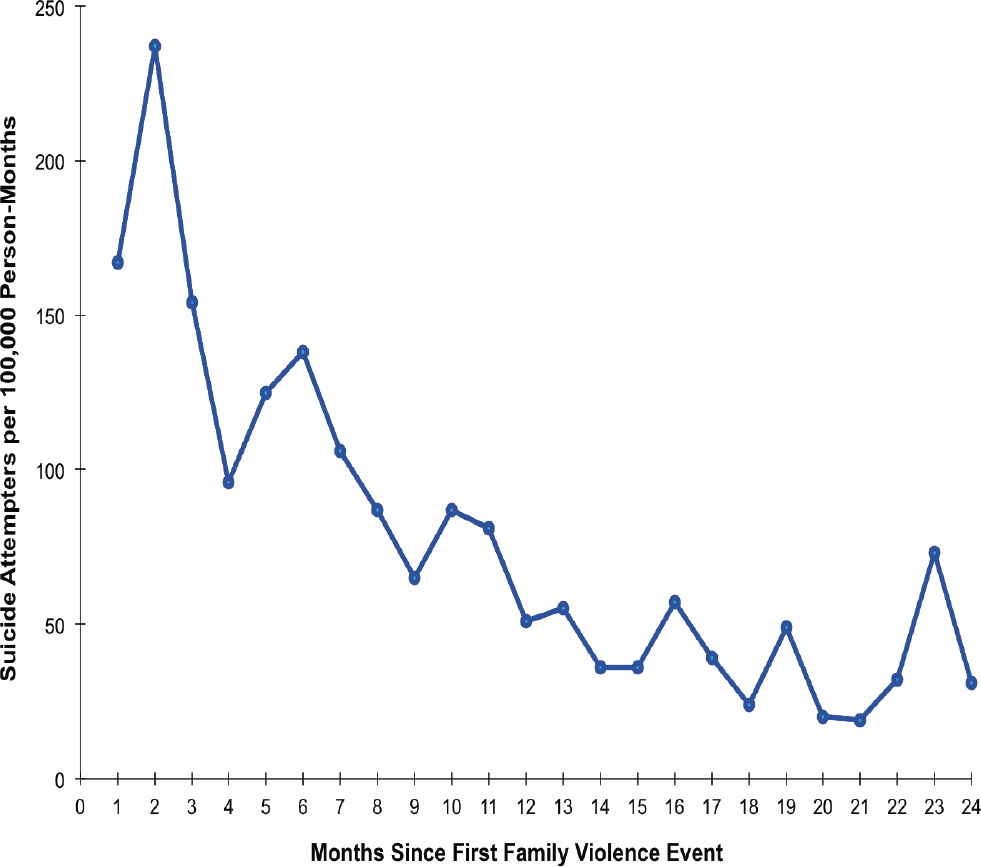

Ursano emphasized that “if you want to understand suicide, you have to study attempts as well as completed suicides. Suicide attempts are 10 to 20 times more frequent. There are differences to learn about as well.” In addition to a small (1–40 soldiers) unit size increasing the odds of previous suicide attempts (Ursano et al., 2017), documented family violence is an important risk factor. The HADS analyses found that the odds of suicide attempts were significantly higher for both perpetrators and victims of family violence, compared with families without documented violence. The highest risk was in the initial months following the first family violence event (Figure 3-2).

In response to a question posed by Frost about family violence, Ursano responded that childhood exposure to violence—and adverse events broadly (i.e., adverse childhood events)—is correlated with suicide risk. He noted

SOURCES: Taken from Robert Ursano presentation, April 25, 2023; Ursano et al., 2018.

that STARRS research shows that attachment style and how we relate to others predicts suicide. However, these attachment styles have different risks at different times (e.g., suicide risk prior to entering the Army versus after joining the service). He explained that STARRS-LS survey data can be used to answer more questions about predictors and correlates.

del Pozo was interested in hearing about when people in military studies seek help, noting his personal experience in law enforcement and that help-seeking is viewed as a detriment to an officer’s career trajectory. Ursano concurred with this observation and explained that he uses the term barriers to care because it captures both stigma and obstacles, such as “having enough money to ride the bus [to receive support].” Learning how to ask for help is an important skill.

Violanti asked Ursano whether he had any insight about what is driving the clusters of suicide attempts in small units. Ursano explained that the term cluster was used because it is unknown whether these clusters have a contagion element or whether they might derive from unit stressors, such as intense operations, isolation, poor leadership, and individuals exposed to the same negative stressor. Ursano also mentioned a study in the Air Force with positive results. This study looks at entry to service during basic training. The teams identified a peer as “someone who they would listen to”; these peers then received special training on assisting others and recognizing when someone may need additional help, thereby seeding support, essentially.

Planning committee co-chair Joel Greenhouse (Carnegie Mellon University) asked Ursano to expand upon the data available at entry in the longitudinal NSS. Ursano responded that the NSS was a model that could be used for law enforcement. This survey asks about suicide ideation or attempt in the past, “what things you do well” versus “what things do you do poorly,” personality traits such as optimism and sociability, and degree of social support, as well as providing baseline data on mental health. All those individuals are followed longitudinally using their administrative data, including medical data. Any suicides or suicide attempts are identified prospectively. Other questions such as “do you like rollercoasters” and “do you wear your seat belt?” measure emotional reactivity and risk behavior, which have also been shown to have predictive power.

Planning committee co-chair Vickie M. Mays (University of California, Los Angeles) noted that many law enforcement officers have a military background; she questioned whether a deidentified data set could be created for studying these overlapping populations. Ursano noted that this has been done with sleep disorders in hospitals, in order to understand mental disorders; however, this was all conducted within DOD. Ursano suggested that in any survey of law enforcement officers, asking permission to link with a respondents’ Department of Veteran Affairs and DOD data would

be key. Although it would require many approvals and specific language to meet multiple institutional review boards’ requirements, the latest survey language could be adopted.

In response to a question posed by Greenhouse regarding pessimism, Ursano explained that there is some debate whether optimism is a construct or a continuum. No stigma is present with “building the muscle of optimism,” so this can may be possible to use as an intervention via direct or internet-based learning modules. Ursano explained that areas for personal improvement could be identified using personnel assessments, such as the NSS, before an individual enters military service or law enforcement. Using these response data, classes could be presented as skill-building for improving resilience; specific classes for different groups would be aimed at, for example, increasing optimism or sociability (i.e., low and high degrees of sociability predict suicide). Similarly, Mays asked whether the point at which a psychological profile is created for a person entering service would be a natural place to collect data. Ursano stated that servicemembers complete the Tailored Adaptive Personality Assessment System upon entry, which identifies 12 personality facets. However, Ursano urged caution with how data at entry are used for a workforce, citing as an example that 70 percent of those who reported a suicide attempt prior to service completed their service and did not have later attempts.