Measuring Law Enforcement Suicide: Challenges and Opportunities: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 4 Complexities of Death Classification and Sources of Bias

4

Complexities of Death Classification and Sources of Bias

This workshop was devoted to approaches to measuring law enforcement suicide. However, several factors may influence reporting or detecting suicide events. This chapter focuses on the complexity of death classification itself and some of the ways in which bias can be present.

PERSPECTIVE OF A PSYCHOLOGIST

Thomas Joiner (Florida State University) discussed why people die by suicide and why classification of suicide is complex. He explained that the intent to die is not always obvious. He walked the audience though four examples of real cases.

- Anorexia nervosa: A young person was hospitalized for this condition, and it was explained to them that death would occur by lack of eating. Upon discharge, the patient resumed restriction of their diet and died. While in the hospital, the young person was asked about suicide and genuinely expressed having no intent to die. Joiner argues this was not a suicide because the young person was not intending to die.

- Substance abuse disorder: Joiner next shared an example of a person who abused alcohol. It was explained to the person that he was consuming alcohol at a level that would be lethal if he did not stop. Indeed, the person did not stop drinking and died from an alcohol-related cause. Joiner argues this was not a suicide because the person was not intending to die.

- Psychosis: A man in an inpatient psychiatric unit was psychotic and believed he could fashion objects with his mind. His delusion was similar to what could be done with a 3D printer, and he explained that he could create an object like a bridge between two tall buildings. The man later walked outside a building and fell to his death. Joiner argues this was not a suicide because the man was not intending to die.

- Subclinical major depressive disorder: This example involved a man who (a) could not sleep; (b) was riddled with self-hatred; and (c) had been thinking and obsessing about death. Joiner explained that these are three symptoms of major depressive disorder, but at least five are required to meet diagnostic criteria. The man died by a self-inflicted gunshot wound by himself while in his home. Joiner stated this was absolutely a suicide because the man was intent on dying.

He contends that if mental disorder is viewed broadly to include subclinical conditions and symptoms, then everyone who dies by suicide has some form of a mental disorder.

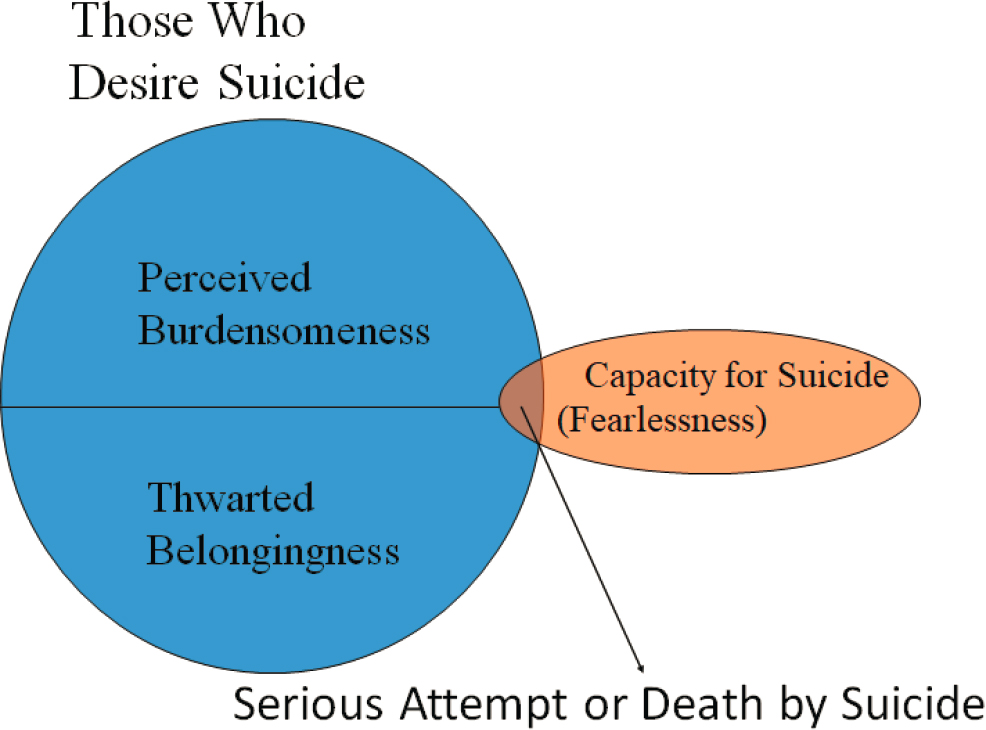

Joiner also discussed patterns of suicide that show variation over time by gender, but he noted that a lot of data that show trends use gender as a binary construct, thereby excluding persons who identify as transgender or nonbinary. Joiner then turned to a theory he has developed over the course of his career that he uses to conceptualize suicide and guide classification (Figure 4-1). He explained the logic involves a perception of being a burden on others and having a thwarted sense of belonging, which is synonymous with loneliness. Joiner posits that when these two states become severe and intractable, a desire for suicide develops. However, most people do not translate suicidal desire into any kind of suicidal action, including a fatal behavior. As other presenters in the workshop indicated, most suicidal actions are nonfatal. Joiner’s theory argues that people who translate suicidal ideation into action are those who have a capability for suicide or fearlessness, which Robert Ursano (Uniformed Services University) also discussed in the context of the measures for emotion reactivity and risk behaviors that are used in the Army. Joiner stated that this fearlessness is above average in some occupations, including law enforcement.

CHALLENGES OF DETERMINING MANNER OF DEATH

A panel of three death investigators discussed factors that influence similarities and differences for determining manner of death: Kelly Keyes is a forensic research scientist (RTI International) and a former coroner’s investigator in the Orange County [California] Sheriff-Coroner’s Office;

SOURCE: Taken from Thomas Joiner presentation, April 26, 2023; adapted from Van Orden et al., 2010.

Bobbi Jo O’Neal is a registered nurse, board-certified medicolegal death investigator, and elected coroner (Charleston County [South Carolina] Coroner’s Office); and Michelle Aurelius is North Carolina’s chief medical examiner and a clinical professor of pathology.

O’Neal explained that state statutes determining whether a death is investigated and an autopsy is required vary. The manner of death is a determination of a homicide, suicide, accident, natural death, or undetermined cause of death. O’Neal and Keyes are on the board of directors for the International Association of Coroners & Medical Examiners; an issue they see that could be perceived as bias is lack of training and resources. O’Neal underscored that many jurisdictions in the United States do not have the resources to pay for an autopsy or toxicology testing.

Keyes previously worked as a medicolegal death investigator in a very large jurisdiction—three million people—and it often had two suicides a day. She explained that a medical examiner or coroner should be a neutral representative to investigate deaths when they receive different narratives from family, friends, and coworkers. However, neutrality will not always

be possible; in some places the coroner is part of a law enforcement agency, and in other places it is a job that pays poorly. Keyes shared that there are stories of it being a secondary job with “people working for $3 per hour.” She raised another complication that could result in error: death investigators will often know law enforcement officers. “We are on the scenes with these law enforcement officers every day, so we either know the officer or we know people on the scene,” said Keyes. She noted that California is a public record state, so any information a death investigator receives may be impacted by stigma (e.g., a spouse may not want to divulge information because it will become public record).

Aurelius concurred that death investigations vary by each state in the United States, and she emphasized that they can sometimes vary even within a state. As a forensic pathologist, together with her death investigator colleagues, she is looking for a preponderance of evidence that someone died by their own hands. However, each of these cases can be very complicated. When a death investigator arrives on the scene, the loved one often cannot talk to an investigator. Aurelius stated, “They are in a state of grief that is so extreme—the worse moment of their life—and it is not the point or appropriate to have a conversation.”

Keyes raised factors such as timeliness, the nature of the process, and accreditation. She stated, “There are not a lot of accredited offices in this country—out of 2,200 coroner and ME [medical examiner] offices, maybe 200 are accredited.” The goal of an accredited office is to have 90 percent of cases completed in 90 days, but investigations can take a while, especially for toxicology.

O’Neal explained that even when the cause of death might be obvious, the manner of death can be very difficult to identify. She provided an example of an officer purposely driving into a tree, which was a frequent example offered throughout the workshop. She explained, “It can be very difficult to determine if there was an intent to take their own life, especially if there was not a suicide note.” She underscored that this determination is an opinion, and that different investigators might reach a different determination with the same case. She noted that bias against determining the manner of death a suicide can certainly be present with line-of-duty deaths, when an officer is in their uniform, at work, and used a service weapon.

Keyes raised the complexity that these investigators are often elected officials, so a high-profile case could result in a call from the County Commissioner’s Office to whom they report exerting undue influence over the investigation. Aurelius stated her office is not within law enforcement; it is a statewide office that covers 10.6 million people. As result, different resources are available, even for their many rural areas. She noted that her system includes an additional layer of review, which helps mitigate bias.

Keyes explained that there is a lot of variability by jurisdiction. While one area may have a forensic pathologist trained as a physician, another jurisdiction may have no requirement other than being age 18 (with no high school diploma required); this person may also be the local mortician. Many trainings are offered, but the cost or time (even when they are online) in a small jurisdiction comes from the same funds that pay for gloves and body bags.

RESEARCH ON THE ROLE OF SYSTEMIC AND UNCONSCIOUS BIAS

Melanie-Angela Neuilly (Washington State University) characterized her perspectives as pertaining to what qualitative research methods can yield. She argued that mortality statistics are the aggregation of individual decisions—cultural, legal, and institutional—in the U.S. death certification system that result in unconscious bias and errors.

Neuilly’s research indicates that unconscious error stems from who can pronounce, classify, and certify death, as well as factors such as the qualifications of coroners, minimum age and education for a death certifier, and selection process for certifiers (Ruiz et al., 2018). Factors such as the dearth of forensic pathologists in the United States and high caseloads also contribute to classification errors (Neuilly, 2022). Among expert populations, a forensic pathologist’s gender can influence classification: male death certifiers are more likely than female certifiers to classify deaths as homicides than suicides or accidents (Hsieh & Neuilly, 2019). She also discussed research still in development about the role of bias in the general population for decedent characteristics (e.g., age, race, sex, social class) and case characteristics (e.g., context clues on substance use, mental health, conflict, or instrument of death). Neuilly identified possible ways to reduce these forms of unconscious bias:

- streamlining systems and training;

- building redundancies and checks and balances—including mortality review teams and psychological autopsies; and

- artificial intelligence (which could be a threat or promise), as long as human bias can be mitigated in the training algorithm.

THE IMPACT OF STIGMA ON REPORTING AND BIAS

The topic of stigma was addressed at various points throughout the workshop, including in Chapter 2. It is important to understand the impact of stigma on bias in measuring law enforcement suicide. Planning committee member Brandon del Pozo (Brown University) explained that law

enforcement agencies may want to downplay suicides because of stigma; they may report a suicide by a firearm instead as an “accidental discharge while cleaning a weapon”; the purposeful ingestion of narcotics might be described as “fentanyl [getting] through their skin while processing evidence.” Hope Tiesman (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [NIOSH]) asked about injury events that might actually be suicides; del Pozo affirmed this occurrence and stated that one of the most vexing investigations he conducted while in Internal Affairs involved a single-vehicle crash by a police officer in another jurisdiction. Additionally, stigmas may stem from cultures (e.g., racial and religious) that may resist calling intentional accidents suicides, thereby influencing the accuracy of the detection of suicides.

Anthony Arita (Department of Homeland Security [DHS]) acknowledged that a number of factors impact the reliability of the data in the Suicide Mitigation and Risk Reduction Tracking System. He commented that, as with law enforcement in general, “there is a general guardedness about mental health issues that is exacerbated by security clearance risks if an officer reports suicidal ideation or behavior.” Stigma around seeking help or engaging in treatment is pervasive in DHS and other agencies, and it is compounded by distrust, confidentiality concerns, privacy matters, and lack of psychological safety. As a result, all of these occupational culture factors impact what is reported, as well as the quality of what gets reported. Arita cautioned that reporting on suicide attempts will be unreliable.