Measuring Law Enforcement Suicide: Challenges and Opportunities: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 5 Methods for Measuring Suicide

5

Methods for Measuring Suicide

Joel Greenhouse (Carnegie Mellon University) introduced the methods discussed in this chapter as approaches that do not necessarily have specific examples using suicide data, but that offer examples, or case studies, of how these methods could apply to measurement of law enforcement suicide. These methods offer ways of enhancing existing data sources by using modern techniques, such as data integration.

DATA LINKAGE

Lisa Mirel (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics) explained that she wanted to plant some seeds about how to think about ways of integrating data, stating that data linkage is a methodology being considered for use in evidence-based policymaking. She noted that data linkage is a powerful and efficient mechanism for producing policy-relevant information by bringing together information to create a new, richer data source and allowing the construction of longitudinal events with passive follow-up. Much of the work she described came from her time as director of the Data Linkage Program at the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Examples of self-report data in health include surveys that collect information from a targeted group to measure factors such as health status, well-being, and access to benefits. This is in contrast to other data that are collected about health for programmatic purposes, which could be from administrative data. Survey and administrative data can be linked; for example, an NCHS health survey data was linked to administrative data

from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development for recipients of federal housing assistance. This linkage has supported informing key policy-relevant questions that could not have been answered with either source alone.

Mirel emphasized that prior to embarking on a linkage process it is important to define what the question is and why it requires data linkage. She explained that while the linkage process itself can be somewhat time intensive, the process to have data-use agreements in place can be very lengthy. The lifecycle for data linkage ends with disclosure protection because there is much more information about a person available once data are linked. The linkage lifecycle consists of the following steps:

- Determine feasibility of linking: coverage, data quality of linking variables, questions to be answered.

- Determine data ownership and data-sharing agreements, requirements, and limitations on use.

- Link the data, manage data security, perform data-quality checks, document processes, create curated linked files.

- Make the linked data accessible while ensuring disclosure protections.

Figure 5-1 illustrates how data linkage could work. It is important to note that because of coverage issues, all records may not be linked. Mirel explained that, while a match rate of 30 percent may seem low, it represents the degree of overlap between the files being linked. Because of this issue, she reminded researchers that a limitation of linked data is the potential for a limited number of analyses for certain subpopulations.

Mirel explained that one approach to linking data is to include two phases: (1) a deterministic match that uses Social Security numbers (SSNs), and (2) probabilistic matching techniques to identify likely pairs using identifiers other than SSNs. A deterministic match could use identifier fields such as names, state of residence, and date of birth to compare for validation. This data set becomes the “truth deck” used later to estimate Type I and Type II errors. Probabilistic matching techniques identify likely pairs using identifiers other than the SSN, which is not used to score pairs; instead, it is used to measure linkage accuracy when the SSN is available.

Factors to consider when linking data are linkage eligibility, linkage error, and analytic considerations. Linkage eligibility could include consent and whether there is sufficient personal identifiable information to conduct the linkage. Analytic considerations include data quality, coverage, data limitations and inference, and timeliness. Guidance from the Federal Committee on Statistical Methodology emphasizes that transparency is essential for proper inference across three main domains of quality: (1) utility, (2) objectivity, and (3) integrity (Federal Committee on Statistical Methodology, 2020).

*To be considered eligible for data linkage, linkage consent must be granted, and participants must provide at least two of the following identifiers: valid Social Security number (SSN), valid data of birth (month, day, and year), or valid name (first and last).

NOTE: PII = personal identifiable information.

SOURCE: Taken from Lisa Mirel presentation, April 26, 2023.

Mirel identified issues and opportunities with data linkage for researchers to consider: (a) agreements and data sharing, (b) linkage methods, (c) quality of linked data, and (d) data accessibility. Ultimately, successful linkages rely on several factors:

- support and adequate resources for both entities;

- consensus on data management responsibilities;

- agreement on secure access;

- commitment to high-quality data standards;

- mutual understanding on why sources are being integrated; and

- investigation of the strengths and limitations of the data and documentation of potential bias and error.

Using health data linked to the National Death Index (NDI), she provided examples of past research that examined suicide risk by such factors such as place, sex, marital status, family size, chronic disease, and psychological distress (Denney, 2010; Denney et al., 2009, 2015; Hockey et al., 2022). Mirel concluded by encouraging researchers to continue to identify and integrate data needed to answer policy questions, utilize innovative technologies, and explore alternative data sources for linkages.

Greenhouse asked what could be put in place to make this easier in the future for government databases. Mirel responded that the Standard Application Process established by the Office of Management and Budget could serve as a model for establishing model data use agreements. Another area of opportunity is privacy-preserving record linkage as a way share data without sharing the direct identifiers.

CAPTURE-RECAPTURE

Capture-recapture—sometimes referred to “mark and release,” derived from the practice of measuring phenomena in the wilderness—is a sampling technique used to estimate population size. Planning committee member Brandon del Pozo (Brown University) explained that this technique collects sample data at one location at different points in time by marking individuals in a closed system. An advantage of this technique is that it enables researchers to track population changes over time; a disadvantage is that individuals must remain in the area of research with definite boundaries.

del Pozo illustrated this method using fish and a pond. Given that a pond is a closed system and one assumes fish are not being removed and are evenly circulating, they can be counted and tagged at the initial capture and released back into the pond. The next stage, recapture, divides the tagged fish by the percent of marked fish in the sample. This method can be used to impute the population in the pond and is improved with repeated capture-recapture samples, which can be averaged to arrive at the estimated total.

In two separate studies in Massachusetts and Kentucky, the capture-recapture method was used to estimate the prevalence of opioid use disorder using administrative data (i.e., “ponds”), with data sets from sources such as emergency departments, death registries, and benefits claims. These were then used to estimate the prevalence of the disorder in each state (Barocas et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2023). Del Pozo also discussed a study estimating the number of homeless deaths in France, which also used the capture-recapture method (Vuillermoz et al., 2014). The corollaries from this study to measuring law enforcement suicide in the United States include (a) population (homeless = law enforcement), (b) outcome (deaths = suicides), and (c) pond (France = United States).

It is important to note that this method does not rely on the first capture and recapture; rather, it uses repeated capture-recapture samples to account for measurement error. In summary, these studies were offered for a proof of concept; their use of administrative data can be translated from wildlife research as follows:

- Capture-recapture in the case of law enforcement suicide consists of detecting appropriate cases in various administrative data sets.

- The unit of analysis is the bounded areas (e.g., the lake or forest); in this case it would be the United States or individual states.

- The different parts of the “lake” or “forest” are the different bodies of administrative data present within the bounded area.

- In wildlife research, the recaptures are prospective, but administrative data set recaptures are retrospective.

Success of this application depends on accurately linking data at the individual level in a national setting.

COMBINING MULTIPLE DATA SOURCES

Greenhouse noted that many previous speakers characterized their data collection systems as surveillance systems, using a term from public health, where surveillance is the ongoing, systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data. Greenhouse concurred that the public health perspective is a useful framework for assessing and understanding law enforcement suicide. This framework includes the following steps:

- Surveillance: What is the problem?

- Identify risk and protective factors: What are the causes?

- Develop and evaluate interventions: What works and for whom?

- Implementation: Scaling up effective policy and programs.

This approach will not only help establish a baseline for assessing the magnitude and trends in law enforcement suicide, but also provide a framework for evaluating the effectiveness of intervention policies and programs.

Individual data sources—such as federal collections (e.g., Law Enforcement Suicide Data Collection [LESDC], National Violent Death Reporting System [NVDRS]), surveys, nongovernmental systems, and investigator-led studies—are unlikely to provide answers for many questions-of-interest, such as identifying risk factors, about law enforcement suicide. However, combining information from multiple data sources has great promise. Greenhouse observed that there is long history in science that demonstrates combining information from multiple data sources can enhance a data set by adding additional subjects or variables. Greenhouse explained that this approach is known across different disciplines by various names, including data integration, data blending, data fusion, and research synthesis. These approaches were identified more than 30 years ago in independent reports from the Government Accountability Office (1992) and from the National Research Council:

TABLE 5-1 Data Integration Examples to Study Law Enforcement Suicide

| Research Questions | Linked Data Source | Publication |

|---|---|---|

| How do risk factors for suicide compare among correction officers and police officers? | NVDRS + ACS | Zimmerman et al. (2023) |

| How do Army suicide rates compare to suicide rates in the general population? | NVDRS + CPS | Griffin et al. (2021) |

| What is the relationship between suicide mortality, family structure, and SES? | NHIS + LMF | Denney et al. (2009) |

NOTES: ACS = American Community Survey; CPS = Current Population Survey; LMF = Linked Mortality File; NHIS = National Health Interview Survey; NVDRS = National Violent Death Reporting System; SES = socioeconomic status.

SOURCE: Taken from Joel Greenhouse presentation, April 26, 2023.

Combining information from disparate sources is a fundamental activity in both scientific research and policy decision making. The process of learning is one of combining information: we are constantly called upon to update our beliefs in the light of new evidence, which may come in various forms.

—National Research Council (1992)

Combining Information: Statistical Issues and Opportunities for Research

Committee on Applied and Theoretical Statistics

Examples of this approach have been incorporated into statutes such as the 21st Century Cures Act (2016) allowing the Food and Drug Administration (2023) to use “real-world data,” including electronic health records, claims data, disease and device registries, and mobile health devices to inform regulatory decisions. Greenhouse provided an overview of a study that combined multiple data sources (e.g., claims data with results from multiple randomized controlled trials) to investigate the potential selection effect of exclusion criteria for participation in clinical trials for depressed youths on the generalizability of the trial results. The specific illustrative case study was an investigation of the relationship between antidepressant drug therapy and the risk of suicidal behavior in depressed youth (Greenhouse et al., 2017). The applications of data integration to study research questions about law enforcement suicide are provided in Table 5-1.

VISION FOR A 21ST-CENTURY DATA INFRASTUCTURE

Robert Groves (Georgetown University) provided an overview of the vision articulated in a consensus study by the Committee on National Statistics (CNSTAT) titled Toward a 21st Century National Data Infrastructure: Mobilizing Information for the Common Good (National Academies

of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [National Academies], 2023). As chair of CNSTAT at the time of that consensus study, Groves explained that its goal was to support agencies whose mission is to produce and monitor the welfare of the country using empirical data. He commented that, as the panel for this report has learned, the way the United States monitors the country (using surveys with probability samples, censuses, and related statistical tools) is “fraying on the edges.” These changes, which risk inaccuracies in the statistics, are linked with increasing costs to the agencies conducting data collections.

During a CNSTAT Big Data Day in 2018,1 it was discovered that many research and development projects throughout federal agencies involve combining survey data with administrative data and other sources to address weaknesses in survey methodology. Groves explained that the common good is served through deep respect for privacy and confidentiality concerns of those whose attributes are measured in these data and used solely for statistical purposes. The importance of these statistical uses, and other attributes of this vision, are explained in Box 5-1.

Groves noted that a bipartisan commission made recommendations leading to the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act (2018; hereafter,

___________________

1 https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/05-11-2018/cnstat-public-seminars-big-data-day-2018

Evidence Act). There is great potential in this legislation. “The Evidence Act granted statistical agencies the right to acquire federal program-agency administrative data for statistical purposes unless such use is prohibited by another law” (National Academies, 2023, p. 114). He concluded by offering key takeaways for this vision of this infrastructure (Box 5-2).

Greenhouse asked whether an individual statistical agency could move forward to blend data as envisioned in this data infrastructure. Groves responded that the Office of Management and Budget (OMB)—where the chief statistician sits—would need to issue the regulatory language that an agency director (e.g., Bureau of Justice Statistics [BJS]) would need to implement it. Meanwhile, BJS could identify programmatic data that could be blended once such guidance is issued by OMB. Groves noted that it

may likely take some time for legal counsels from operative agencies to implement the Evidence Act. Lastly, BJS would need to ensure that there is no other law that would explicitly prohibit an agency from sharing data.

NEW MEASUREMENTS IN THE NEW DATA INFRASTRUCTURE

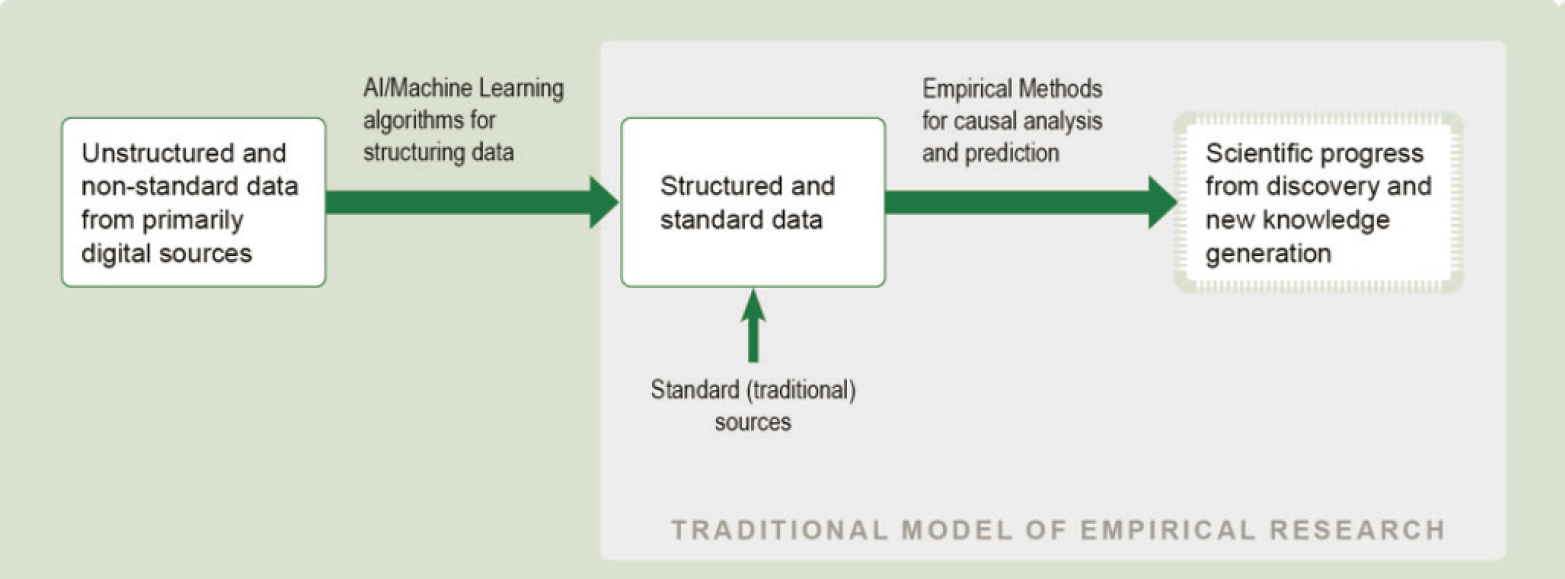

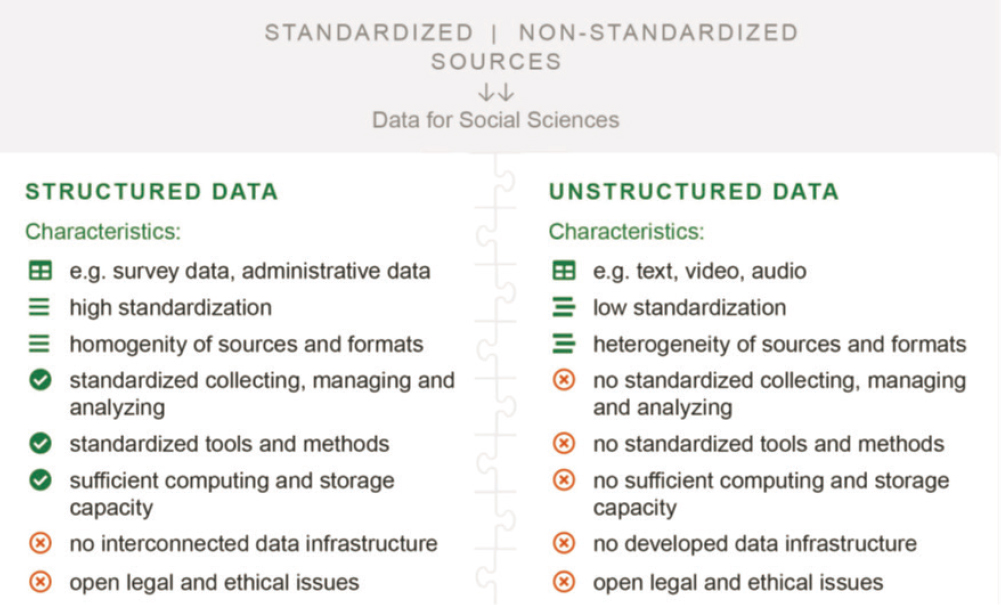

Frauke Kreuter (Joint Program in Survey Methodology) expanded on the vision Groves outlined and discussed her work with the Coleridge Initiative, a nonprofit organization that supports groups of state and local data holders working through the legal and ethical issues of sharing data and extracting information out of blended data projects. Kreuter explained that the traditional model of empirical evidence uses structured rather than unstructured data (Figure 5-2).

However, advancements with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning can now harness unstructured data from nonstandard—primarily digital—sources (Figure 5-3). The critical element often overlooked is the decision-making to move from an unstructured to a structured data source. Kreuter emphasized the importance of making this shift transparent, in that both types of data sources are being used to produce a statistic.

Kreuter referenced a data infrastructure initiative in Germany, with which she is involved, to enhance data sources and build environments in which these multiple sources can be used in economic contexts. She mentioned that there are ongoing efforts in Europe to unlock administrative data sources. Sometimes significant investments are made to set up administrative data research facilities, but they “sit like graveyards” if it is not determined in advance what type of data are to be generated in these data-linkage facilities. She also raised an inherent complexity in administrative data: state-maintained databases that contain data on an activity crossing state lines are difficult to merge and analyze.

She explained that the Coleridge Initiative trains government employees in the basics of statistical models and prediction and machine learning, but also in other crucial aspects—data, content, and results—that require different knowledge and skill sets (Kreuter et al., 2019). The goal is to give everyone a seat at the table, so they are at least proficient in these elements that feed into the end results of new metrics. Kreuter emphasized that data science should be viewed as a team sport (Japec et al., 2015):

- A domain expert is a user, analyst, or leader with deep subject matter expertise related to data, their appropriate use, and their limitations.

- A system administrator is a team member responsible for defining and maintaining a computation infrastructure that enables large-scale computation.

NOTE: AI = artificial intelligence.

SOURCE: Taken from Frauke Kreuter presentation, April 26, 2023.

SOURCE: Taken from Frauke Kreuter presentation, April 26, 2023.

- A methodologist is a team member with experience applying formal research methods, including survey methodology and statistics.

- A computer scientist is a technically skilled team member with education in computer programming and data processing technology.

Kreuter concluded by offering lessons learned in other applications that are useful with new projects to combine data: (a) creating new measures out of linked data is not enough—the effort has to be tied to a product; (b) research questions need to guide decisions on measurements and data sources; and (c) data science is a “team sport” and needs to be treated as such, as outlined above.

Anthony Arita (Department of Homeland Security) noted that suicide data studies are at different levels of “maturity” and various approaches have been discussed for data linkage and integration. He questioned how to move forward to improve the measurement of suicide in a way that reflects the understanding of the most relevant variables to answer the most pressing questions and help reduce stigma and suicide. Kreuter cautioned not to get “hung up” on solving all problems and encouraged moving forward with pilots. Greenhouse remarked that through the initiatives discussed by Robert Ursano (Uniformed Services University), the military has developed comprehensive research plans that could be a model strategy. Vickie M. Mays (University of California, Los Angeles) reminded the audience that

resources and funding are critical to the individual studies in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (STARRS) program. Jeffrey L. Sedgwick (Justice Research and Statistics Association) underscored this point, noting that funding sources would be needed to assist with implementation.

LINKING LAW ENFORCEMENT PERSONAL IDENTIFICABLE INFORMATION WITH THE NATIONAL DEATH INDEX

Rajeev Ramchand (RAND Corporation) framed his insights as drawn from two primary sources. First, he conducted a study with funding from the National Institute of Justice to examine what law enforcement agencies were doing to prevent suicide and how they aligned with best practices. Second, Ramchand was part of the response by the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which sought to get higher-quality data for improving surveillance efforts (Ramchand et al., 2021).

Ramchand advocated that, although his view is controversial, he believes that the best source of data on suicide among current and former members of law enforcement will be derived from personal identifiable information (PII; e.g., Social Security numbers or dates of birth) for law enforcement officers, linked with official death records. The next step would be to confirm who died by suicide and who died from other causes. It is paramount to obtain PII for law enforcement officers—PII for those who have not died is necessary for optimizing mortality surveillance efforts and constructing suicide death rates. Ramchand suggested that this approach should be the “North Star” in this effort.

Ramchand argued that methods reliant on data from interviews with family members should be viewed with healthy skepticism; some families do not want to contribute information about the loss of their loved one and researchers should respect their wishes. In his research with next of kin of those who died by suicide in New Orleans, 17 of 60 family members accepted an invitation to be interviewed (Ramchand et al., 2017). He implored, “We must allow these families agency and allow their contributions to our prevention efforts to be their choice.” Ramchand shared his experience when a surviving spouse told him she was horrified when her husband’s image was used in brochure materials to prevent suicide, which was published before she had a chance to tell her children how their father died.

While voluntary reporting of law enforcement suicides and details from family members about these deaths can yield important information, Ramchand contended that these sources will never be comprehensive. If the onus is on law enforcement agencies, Ramchand noted, one has to ask how the 18,000 agencies document and record deaths of officers and

retirees that do not occur in the line of duty. This is challenging because very few suicide deaths are classified as suicides immediately. In the United States, 50 percent of deaths that are officially classified as suicides are classified within two months, fewer than 75 percent are classified within three months, and 93 percent are classified at six months. Ramchand questioned whether it is reasonable to require law enforcement agencies to follow up with coroners and medical examiners a year after a death to record how the officer died.

Another challenge with existing approaches, according to Ramchand, are industry codes used in data sets, which are insufficient for identifying an occupational group and inadequate for this purpose. He cited past attempts with his colleagues to use NVDRS data, when they found that 13 percent of occupational codes and 17 percent of industry codes were missing (Griffin et al., 2021).

A variety of ways to link PII data with death data is available. Ideally, organizations with law enforcement officers as members (e.g., police unions) would submit their data on employees or members to local, state, or national agencies that track vital statistics. These offices would search their files to identify those who died and the manner of their death. If this could be done securely and systematically, Ramchand asserted, this would provide the most complete data under consideration of this workshop. When linked with a cohort of officers, including those who have not died, this approach would enable researchers to calculate death rates. This approach would also enable researchers to estimate risk and identify the specific groups of the law enforcement community that are at a greater risk of suicide than their counterparts.

There are trade-offs between linking data at the city or state level versus the national level. Local linkage may be advantageous in that it could be done quickly. However, this method would only catch deaths of law enforcement officers who died in the same city or state where they worked. Linkage with the CDC’s NDI solves this problem for deaths that occur in a different city or state. However, Ramchand posited, these data may be older; thus, there would be a lag between the year of death and the year in which the rates are available.

The linkage method Ramchand advocated has precedence, as it is used to estimate the suicide rate among veterans. Historically, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has relied on data if a decedent had used VA health services or benefits, or if veteran status was coded on death certificates. Beginning in 2010, the VA and Department of Defense (DOD) have compiled a list of all veterans annually and submits it to the NDI. There is more confidence in the accuracy of the veteran suicide rates since 2010. Claire Hoffmire and her team of epidemiologists at the VA found that the prior method overestimated the suicide death rate among veterans. Ramchand

speculated whether the barriers to securely linking personnel data with death data seem insurmountable or whether they are distracting researchers when this alternative method may yield more reliable data.

Ramchand noted that he recently served on the Suicide Prevention and Response Independent Review Committee for the DOD. He asserted that researchers should question the overreliance on mental health solutions and whether it has resulted in overlooking administrative and bureaucratic solutions. For example, when an officer is asked about stressors, while trauma often does not come up, bureaucracy and administrative challenges are cited. Other factors are having to work on the weekends and not being able to spend time with their families (especially for young officers). These structural changes, including rescheduling and addressing the main causes of stress, need to be considered seriously, rather than simply screening people, referring them to mental health resources, and applying “resiliency” training. Ramchand stated, “I think we should be looking at the structural and systemic issues.”

DISCUSSION

Greg Ridgeway (University of Pennsylvania) said that his career as a statistician largely draws on experience with data collections that are incomplete in some way (e.g., missing data, nonresponse, truncated, censored), and the methodological challenges discussed in the workshop could be avoided if the additional variables needed were known in advance. In his experience conducting policing research, law enforcement agencies are often the most willing to share their data within the criminal justice system; there is a longstanding tradition—almost 90 years—for law enforcement to share their crime data with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), even though it is voluntary.

Ridgeway reviewed the new LESDC, which in 2022 recorded 32 law enforcement suicides—but noted that Blue H.E.L.P. reported 159 suicides in the same year. Clearly, there is a lot of room for improvement. Along with methods for linking data, Ridgeway asserted that more effort could be placed on getting police departments on board to report deaths by suicide, given that only about 1 percent of law enforcement agencies have enrolled in the LESDC to submit data.

Ridgeway echoed ideas offered earlier in the workshop of providing support to encourage reporting. He explained that when agencies report crime data, federal assistance from agencies such as the Bureau of Justice Assistance and Office of Community Oriented Policing Services has often depended on formulas tied to their crime reporting to the FBI. Therefore, agencies that did not submit crime counts in any given year were at risk for being ineligible for the aforementioned types of federal funding. Ridgeway

commented that the federal government could be more aggressive about requiring LESDC reporting and tie it to federal grant eligibility.

Ridgeway commented that capture-recapture methodology discussed earlier is a useful approach that might be necessary in the short term for getting estimates of law enforcement suicide. However, a lot of rich information, such as circumstances and location, is lost when relying on this method alone. Ridgeway advanced the notion of “taxing the agencies until they line up.”

Ridgeway acknowledged Greenhouse’s earlier point regarding risk and protective factors. Ridgeway explained that for more than 80 years, law enforcement agencies were only reporting crime counts to the FBI, without any additional information such as location or victim–offender relationship. These crime counts have only recently begun a “rough, complicated, and tumultuous transition” to an incident-based reporting system. Despite not knowing currently how much crime there is currently in the United States, this is an important transition, moving beyond counts to understanding the risk and protective factors.

Ridgeway concurred with Kreuter’s discussion about the usefulness of artificial intelligence (AI) for this effort; he also emphasized that AI is good at reading and extracting text, which will only improve with time. This provides a lot of potential for more of these curated data sets to become better over time, with the ability of generative AI models to read items such as media reports and obituaries.

Ridgeway closed by pointing out the cost of privacy and commenting that our society is moving in a direction where privacy laws are becoming more restrictive. He capitalized on Groves’ discussion by underscoring that, if privacy concerns can be solved, there is value in promoting the benefits of sharing data. Ridgeway offered examples such as location-sharing with Google to avoid traffic and amassing health claims to identify adverse drug events. He acknowledged that it is understandable that many families may not want identifying information about their loved one who died by suicide to be shared, but this information could be used to help other families by learning about the circumstances that led up to this event and potential warning signs.

Ojmarrh Mitchell (University of California, Irvine) commented that measurement of law enforcement suicide is a salient and timely issue. He noted that there are measurement, statistics, and evaluation opportunities to consider that are possible with the 21st-century data infrastructure vision. He stated that his comments would be speculative because the proposal for integrating data sources to better measure law enforcement suicide has not been spelled out in great detail. Large data sets tend to have rigorous data validation protocols and tend to be of high quality. Mitchell also noted his interest in using these integrated data sets to evaluate prevention efforts. He

expects that these large integrated and blended data sets will be invaluable for measuring suicide as well as its correlates.

Mitchell cautioned, however, that these integrated data sets are not without challenges and limitations. The proposals thus far have not provided sources for granular data on individual psychological functioning. They also have not provided information on how to measure conflicts within data sources while maintaining the transparency of a data collection process. He also noted that challenges with data sharing and ownership, as well as proprietary issues, frequently arise with private data sources, systems, and software. Another matter to consider is that, while suicide among sworn law enforcement officers has been a concern for a long time, some of the newest data collection efforts have broadened the focus to include correctional officers, judges, prosecutors, probation officers, and others. Mitchell concluded by stating his understanding that, while the public data sets would have deidentified data made available to the public, the rarity of this event may mean that someone could be identified by unscrupulous researchers.