Summary

In May 2023, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) released its Equity and Environmental Justice Strategy (EEJS). This document guides NMFS staff in their efforts to address various equity issues under the agency’s purview. Three overarching goals are articulated in the EEJS: “(1) Prioritize identification, equitable treatment and meaningful involvement of underserved communities; (2) Provide equitable delivery of services; and (3) Prioritize equity and environmental justice in meeting its mandated mission.”1

As part of its effort to address the stated goals and advance equity, NMFS requested that the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine provide an independent, third-party review of the data and information needs and availability for assessing equity in the distribution of benefits derived from current fisheries management practices (Box S-1). This study precedes a proposed second study, which would build on this contribution by evaluating equity in select, illustrative fisheries using the information available.

The context and circumstances surrounding the study request made clear that advancing equity in the management of the nation’s commercial and for-hire fisheries was a key objective in requesting the committee’s input. Therefore, the committee’s intent has been to both address the statement of task and consider the broader context of equity. Doing so has required examination of the definition of equity, the relationship of equity to NOAA’s relevant mandates, and the degree to which filling particular information gaps contributes to NOAA achieving its equity-related objectives.

The committee also wrestled with the term primary benefits. In order to understand the questions of where and to whom the primary benefits of fisheries management accrue, which appear to be at the heart of the committee’s first task, the felt it was necessary to understand what primary benefits means. At one level, for example, this could mean a geographic and demographic description of who receives the permits and quotas that NMFS allocates. However, while potentially useful, that interpretation may not result in an adequate analysis for multiple reasons: (1) quotas and

___________________

1 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association Fisheries. 2023. Equity and environmental justice strategy. See https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/s3/2023-05/NOAA-Fisheries-EEJ-Strategy-Final.pdf. P. 2.

allocations vary widely in their nature; (2) a range of benefits may or may not stem from holding permits and quotas; (3) permit and quota holders are not the only potential beneficiaries impacted by allocative decisions; and (4) broader considerations of equity are not limited to distributional concerns. The committee recognized the importance of addressing its statement of task as it was originally interpreted, providing insights on data and information needs for assessing the distribution permits and quotas. As a result, the committee first provided input from this more focused perspective before incorporating discussion of other potential benefits or beneficiaries and the full suite of equity considerations.

WHAT IS EQUITY?

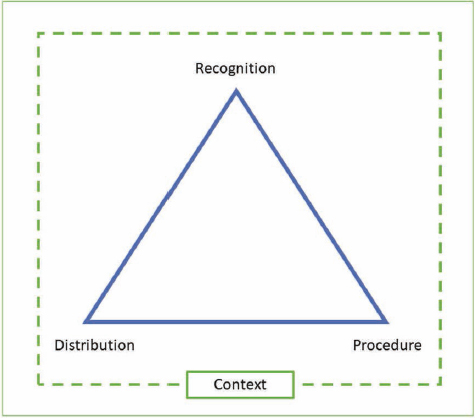

Equity can be thought of as consisting of multiple elements: distributional equity, procedural equity, recognitional equity, and a cross-cutting element referred to as contextual equity (Figure S-1).

SOURCES: Adapted from Franks and Schreckenberg (2016) and Schreckenberg et al. (2016). See McDermott et al. (2013) and Pascual et al. (2014) for alternative visualizations.

The first element, or dimension, of equity is distributional equity. In the context of natural resource management, this dimension considers the distribution of benefits and costs to individuals or groups at various scales. While it may seem straightforward, measuring distributional equity can be quite complex. A wide range of goals and criteria can be applied for assessing distributional equity, some of which may focus on equal distribution among all members, while others seek a distribution that maximizes benefits or minimizes costs to the most disadvantaged. Still others may try to account for potential future members or seek to distribute costs and benefits proportionally according to effort, investment, or other factors. In other words, what may be perceived as a “fair” or “equitable” distribution of cost and benefits to one party may not be viewed as such universally.

As originally interpreted, the committee’s statement of task calls for a focus on the distribution of the primary benefits of fisheries management. However, the committee acknowledges the importance of also considering the additional dimensions of equity (i.e., procedural, recognitional, and contextual), in part because the dimensions interrelate and influence one another.

Recognitional equity involves acknowledging the rights, knowledge, values, interests, and priorities of a diverse array of individuals and groups and incorporating them into management considerations. As an example, in the fisheries management context, this may involve recognition of Indigenous rights, including fulfilling the trust obligation to federally recognized Tribes, and the value of Indigenous Knowledge and Traditional Knowledge. As a second example, recognitional equity may involve both the recognition and potential management consequences of the imbalance in power among individuals and groups.

Procedural equity requires consideration of who is involved in the decision-making processes. It involves the inclusive and effective participation of all relevant individuals and groups. This can be difficult to achieve because of challenges associated with identifying those who once were or may in the future be affected by the outcomes of fishery management outcomes. Important goals of procedural equity are to overcome existing power dynamics, and account for the range of capacities and resources needed to enable the participation of all relevant groups in fishery management decision-making.

Cutting across the other elements of equity, contextual equity considers the social, economic, environmental, cultural, and political history and circumstances that affect other forms of equity. In part, consideration of context can shape which dimensions of equity are prioritized and how subjects of equity are characterized and identified. Contextual equity recognizes that efforts to achieve equity or mediate inequities do not occur against a blank slate.

No single dimension of equity can itself define an equitable system, instead, a complete assessment of the system that integrates elements from each dimension is necessary.

FINDING 2-1: Equity is multidimensional and is more likely to be realized through an approach that accounts for each of the dimensions: distributional, procedural, recognitional, and contextual. (Figure S-1).

NOAA’S MANDATE FOR EQUITY

The legal, regulatory, and policy context surrounding fisheries management in the United States includes multiple instruments and documents that either influence or mandate equity. The committee did not try to identify or enumerate all such instruments and documents, but rather identified select key examples to illustrate how they may map to the framework of equity described above. In many recent relevant executive orders and strategy documents equity and justice are considered deeply connected, so that a commitment to one presupposes a commitment to the other.

The Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (as amended; the Magnuson-Stevens Act or MSA) serves as the primary legislation governing federal fisheries management

in the United States. The MSA sets forth 10 principles, referred to as National Standards, that are required in fishery management plans. Each of the National Standards is accompanied by supporting guidance for their implementation. National Standard 4 is most obviously linked to equity, but National Standards 1, 2, and 8 (Box S-2), and their respective guidance documents, are also relevant.

National Standard 4 specifically requires fair and equitable allocation of fishing privileges, and the associated guidance2 expands on that stating that “An allocation of fishing privileges may impose a hardship on one group if it is outweighed by the total benefits received by another group or groups. An allocation need not preserve the status quo in the fishery to qualify as ‘fair and equitable,’ if a restructuring of fishing privileges would maximize overall benefits.”

National Standard 1 and 2 are also pertinent, as National Standard 1 guidance refers to the “greatest benefits to the nation,” calling for the consideration of who benefits and how. National Standard 1 is also the most directive of the National Standards, without the contingent elements that can be found in other National Standards. National Standard 2 guidelines require the inclusion of “pertinent economic, social, [and] community … information for assessing the success and impacts of measurement measures” in fisheries Stock Assessment and Fishery Evaluation reports. Finally, National Standard 8 calls for consideration of geographic communities and their participation in fisheries as well as evaluating economic impacts on fishing communities.

___________________

2 The committee recognizes that revisions to the guidance documents for some national standards, including National Standard 4, are underway. The committee is aware of the Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking that was issued in May 2023 (88 F.R. 30934), but for the purposes of this report relied on the existing guidance.

In addition to the MSA, the National Environmental Policy Act includes requirements for meaningful participation in decision-making along with consideration of any social impacts, including equity concerns, that may arise from agency decision-making.

Beyond these key pieces of legislation, a series of executive orders further demands consideration of equity, environmental justice, underserved communities, and Tribes and Indigenous Peoples. Some include definitions of equity with notable procedural, not merely distributional, components.

Finally, the NMFS EEJS released in May 2023, not only sets forth NMFS’s goals and objectives related to ensuring equity in their decision-making and management, but also describes the policy landscape in additional detail.

FINDING 2-3: Existing authority granted to NMFS by the MSA, the National Standards, NEPA, executive orders, and other instruments provides the agency with a clear mandate for a multidimensional and contextual approach to centering equity in its work.

RECOMMENDATION 2-1: The National Marine Fisheries Service should develop and implement a contextual, place-based, and participatory approach to identifying and integrating multi-dimensional equity considerations into decision-making processes in ways that balance previous and more recent mandates. Outcomes of these processes should include, among other things, clear identification of the criteria for, and appropriate subjects of, equity considerations.

DISTRIBUTIONAL EQUITY OF FISHERY PERMIT AND QUOTA BENEFITS

The committee provides a stylized model fishery, which is not intended to represent an ideal, equitable fishery, but rather a fishery for which there is substantial available information to assess distributional equity. This model requires several key assumptions, many of which are not met by the realities of U.S. federally managed commercial and for-hire fisheries. The committee uses these assumptions to demonstrate how difficult it can be to collect essential information even for the purpose of measuring the current distribution of permits and quota. In particular, the use of the model fishery illustrates the importance of having a full suite of demographic information to assess the extent and nature of fishery engagement among various groups, but notes this is necessary but not sufficient for assessing distributional equity. For instance, the assessment of equity will require a fair and equitable process for determining the appropriate counterfactual from which to compare and evaluate the distribution across fisheries, time, and regions.

FINDING 3-1: Comprehensive demographic data related to characteristics of permit and quota holders and their geographic locations are required if NMFS is to determine where and to whom the benefits of the issuance of permits and allocations of quota accrue and to meet the intent of Congress expressed in MSA for fair and equitable distribution of benefits as well as to meet commitments made in recent executive orders.

However, various barriers can limit the collection of all the necessary demographic data. Considerable differences exist between regions in their current practices of issuing permits and allocating quota, which can influence whether and how particular categories of information can be collected. For example, additional data collection efforts, beyond what is already being collected, may be subject to the Paperwork Reduction Act or Privacy Act requirements. In other cases, complex permit ownership, such as ownership by vessels, corporations, banks, or LLCs, can make collecting demographic information on “to whom” and “where” benefits accrue either complicated

or impossible. Voluntarily submitted data, despite its potential to provide useful information, creates challenges for assessment, particularly because of concerns regarding the representativeness of the sample provided. banks, or limited liability corporations, can make collecting demographic information on where and to whom benefits accrue either complicated or impossible. Despite their potential to provide useful information, data submitted voluntarily create challenges for assessment, particularly because of concerns regarding the representativeness of the sample provided.

Adding to the challenge, a common factor impacting data acquisition and analysis is the need for significant investments in capacity in the non-economic social sciences within NMFS. A needs assessment within each fishery management region and at the national offices would provide important direction as the agency looks to fill this capacity. Many approaches, from focusing on hiring entry-level staff social scientists to hiring at the senior scientist level, could be effective. Although the committee does not prescribe a solution, it sees value in ensuring that senior leadership (e.g., a lead social scientist position akin to the lead economist position in NMFS) is working on these issues.

Despite the aforementioned obstacles, important work is under way and additional progress is possible. During the committee’s open-session meetings, NMFS and its partners showcased high-quality social science work already being conducted. For example, scientists are expanding and advancing integration of data into dashboards, such those being developed by the Northeast Fisheries Science Center, that provide economic and social metrics for particular fisheries in the region, including supporting continual updates and developing necessary database structures. Others are expanding and enhancing collaborations and partnerships, including developing a community of practice in each region. Partnerships may also provide a solution for overcoming some of the constraints of collecting data within the federal system.

RECOMMENDATION 3-1: The National Marine Fisheries Service should take advantage of current opportunities both within the agency and in academia to expand work on equity by generating dashboards and data summaries that more fully express the distribution of permits and quota holdings in the nation’s fisheries. Progress on these activities need not await more comprehensive discussion of equity or wider availability of data.

RECOMMEDATION 3-2: The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) should develop a guidance document(s) to inform and establish principles that lead to definitions of equity (see, e.g., Recommendation 2-1), and processes for measuring and assessing equity over time by NMFS, regional science centers, and Council staff. This document(s) should parallel guidance documents related to the Magnuson-Stevens Act. For example, NMFS has issued technical guidance that provides national, operational definitions of abundance and exploitation thresholds. Accordingly, even though regional methods for evaluating these thresholds may differ, an integrated, national summary of the status of fish stocks is possible. The committee views the suggested equity guidance documents as working in a similar fashion.

RECOMMENDATION 3-3: The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) should undertake a needs assessment in each region and at the national level that can provide guidance on different investment strategies for developing social science capacity and leadership within the agency. These investments could include staffing focused on early-career scientists or a mix of scientists at different career stages with diverse disciplinary expertise and skill sets, including in research design and qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis. The committee recommends that increasing capacity needs to include, but not be limited to, the leadership level, such as a Senior Scientist for Social Sciences within the NMFS Directorate.

BENEFICIARIES OF FISHERY MANAGEMENT DECISIONS

After examining its task through a focused lens of distributional equity related to benefits that accrue to permit and quota holders, the committee broadened its focus to consider the flow of benefits that accrue from the issuance of permits and quota more comprehensively, recognizing important non-monetary benefits such as cultures, food security, and traditions at the individual, community, and societal scales.

The committee first considered three common categories of beneficiaries: crew, the processing and distributing sector, and communities. Subsequently, the committee considered potential beneficiaries who lost access, who might currently enjoy access and who society may wish to see benefiting were different management policies enacted.

Crew include nonowner captains, deckhands, mates, and those in specialized roles, who are essential fishery participants and who may be significantly impacted by fishery management decisions. While potential benefits associated with serving as a crew member include monetary benefits, studies have also demonstrated the value of job satisfaction, social capital, and identity associated with these roles. Crew positions may also serve as an entry point for new careers in fisheries. However, crew are often highly vulnerable to changes or declines within fisheries, including being only subject to informal employment and pay arrangements. In many regions, crew are generally characterized by lower social mobility, less formal education, and include many immigrant and temporary visa workers.

Beyond those engaged with or on fishing vessels, networks of shoreside facilities, such as processors and distributors, move caught fish to market. Processors and distributors may receive both monetary and nonmonetary benefits that may impacted by fisheries management decisions. For example, fish processing jobs depend on the status and management of supporting fisheries. Providing seafood to consumers also represents a nonmonetary benefit associated with these sectors. Very few studies focus on the social or demographic dimensions of fish processing and distribution. The studies that exist are generally ethnographic studies of specific cases. NOAA’s technical reports are available for some regions, although some are quite dated. NOAA social science reports have articulated several practical and logistical obstacles to characterizing seafood processors and other shoreside businesses.

Communities can also be impacted by fisheries management. According to the National Standard 8 guidelines, “A fishing community is a social or economic group whose members reside in a specific location and share a common dependency on commercial, recreational, or subsistence fishing or on directly related fisheries-dependent services and industries (for example, boatyards, ice suppliers, tackle shops).” Along with monetary benefits, diverse nonmonetary benefits to communities are associated with fisheries management. Fishing communities are diverse, spanning from small artisanal communities in the Western Pacific to large industrial ports in the Northeast—cultural identities across this spectrum are also important.

FINDING 4-1: The beneficiaries of commercial and for-hire fishery management go beyond current permit and quota holders to include others engaged directly in the fishery (e.g., non-permit holding vessel captains and crew), shoreside facilities involved in processing fishery products, the network that distributes fishery product, local and regional businesses that rely directly and indirectly on fishery activity, and local fishing communities.

Efforts to collect the data needed to assess the distribution of benefits among non-permit-holding participants and others have been fragmentary. Data on benefits that accrue to crew come primarily from regional surveys of crew members. Some data related to economic values that accrue in the processing and distribution sectors and in specific fishing communities are available, based

primarily on the value of fish and shellfish landed in particular ports. Fewer data are available pertaining to the processing and distribution network. Work has been conducted to establish indicators of coastal community social vulnerability (CSVI) to inform consideration of the impacts of fishery management on communities. Nevertheless, there are limitations associated with grounding the CSVI and similar analyses in U.S. census data. A primary challenge for NMFS going forward is the need to increase its capacity to design, conduct, and analyze social science data that assess the full flow of benefits from fishery management decisions.

RECOMMENDATION 4-1 The National Marine Fisheries Service should commit to regular collection, analyses, and interpretation of social and economic data to characterize the full flow of benefits and beneficiaries from the nation’s fisheries. The committee recommends collecting, and within the extent of the law, disseminating publicly this information at more regular intervals to adequately assess the impacts of management decisions and changes in fisheries.

RECOMMENDATION 4-2 The National Marine Fisheries Service should continue developing community-level indicators of fishing engagement, dependence, and reliance. However, the committee also recommends further developing products that are not geographically constrained or limited by the spatial resolution of census data, which may not always align with a holistic definition of equity.

CHALLENGES TO DEVELOPING A COMPREHENSIVE APPROACH TO EQUITY

Current NMFS processes generally do not adopt an all-inclusive approach to integrating equity in management. The committee explores the challenges associated with a broader approach to equity. These challenges relate to both structure and methodology. Subsequently, the committee outlines elements of several programs and efforts, both within and outside NMFS, that could inform (but would not by themselves constitute) a holistic approach to equity considerations.

Six principal challenges to implementing a comprehensive approach to equity considerations in fisheries management are identified in the NMFS EEJS and several recent EOs. The first barrier relates to NMFS’s acknowledgment that it has yet to fully identify underserved communities and account for impacts, including past injustices and exclusions, many of which stem from structural barriers within society as well as within the Agency’s approach to_underserved communities and in some cases fisheries science and management more broadly (see, e.g., White House 2022; Carothers et al., 2021; Silver et al., 2022). A second and somewhat related barrier relates to contextual equity. It recognizes historical processes including the long history of some fishery allocation programs, which will make identifying and obtaining demographic data on those excluded from participation and benefits difficult. Those who currently have access and are thereby empowered within the management regime may resist efforts to address prior inequities. The third barrier restricts engagement and access to services. This barrier relates to procedural equity issues related to costs, language, and other geographic and cultural barriers to meaningful participation in fishery management processes. The fourth barrier relates to the highly hierarchical and complex nature of the fishery management process. This complexity under-emphasizes the more nuanced, often qualitative data or Traditional and Indigenous Knowledge that might best inform implementation and assessment of multidimensional equity in fishery management. An unintended outcome is that social science data collection programs, such as the Fisheries Oral History Project, are difficult to integrate into routine management decisions and thus become lower priorities for funding, even though they may offer important insights. A fifth barrier acknowledges that ocean management policies beyond fisheries, such as area closures to protect biodiversity may become more pressing concerns in some

geographies, leading to an under-engagement in fisheries. The final barrier is that of social science capacity within NMFS (see Recommendation 3-3).

FINDING 5-3: A range of challenges is associated with moving toward comprehensively addressing and integrating equity concerns into fishery management decision-making processes, and their realized outcomes. These challenges include those related to diversity and capacity within NMFS and other management bodies, as well as those that are features of the communities (fishing, underserved, Indigenous), which NMFS impacts, those that are part of the larger social-ecological context, and those that stem from the unavoidably complicated nature of assessing equity.

MEASURING WHAT IS VALUED OR VALUING WHAT IS MEASURED?

Given the emphasis on methodological approaches in the statement of task, the committee also identified challenges associated with data and information and the assessment of equity concerns. For example, contemporary governance often emphasizes management goals and targets and identifying measurable indicators that can be monitored to assess progress. The attention is on outcomes or results, rather than administrative processes of policy delivery. Metrological practices to support outcome-based management—for example, setting and measuring standards, targets, criteria, baselines, benchmarks, and thresholds—are seen as key to good governance, allowing for monitoring, transparency, reporting, and evaluation.

However, this approach emphasizes that which is measurable in standardized, quantified, and comparable ways, thereby reinforcing the importance of the things it purports to measure. Governance action then becomes directed toward identified goals and preference is given to those that are more easily measured.

In contrast, multidimensional equity, embedded in context and with key terms subject to interpretation, fits uneasily within a governing logic of standardized, quantified, comparable, and easy to measure indicators. Efforts to ‘make equity fit’ by adopting universal definitions and measures risk perpetuating inequities, by imposing top-down and western conceptualizations of what constitutes fairness. The committee asks then, “if we leave equity out altogether, is it unlikely to be consistently or meaningfully prioritized?”

MOVING FORWARD: RECENT ADVANCES IN IMPROVING EQUITY IN MANAGEMENT

The committee reviewed five federal, state, and international efforts as examples that may offer lessons for NMFS in moving forward to adopt the broader, multidimensional approach to equity. This review supports Recommendation 3-2, which calls for a technical guidance document to support adoption of a holistic approach to equity. While the place-based approach envisioned in the NMFS EEJS is appropriate, it requires NMFS invest in capacity to support regional- and fishery-based approaches. The committee highlights the potential role of social impact assessments, required of fishery management actions, as a framework that could help inform NMFS work on equity in fisheries. The committee also recognizes the Socioeconomic Guidance for Implementing California’s Marine Life Management Act and the International Institute on Environment and Development’s (IIED’s) Site-Level Assessment of Governance and Equity (SAGE) as useful examples for NMFS in informing their thinking. For example, although designed to support efforts by the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity to ensure protected areas are managed equitably, the IIED’s SAGE tool explicitly addresses multiple dimensions of equity, and describes methods to prepare, assess and monitor of management actions.

LEARNING FROM RECENT WORK TO IMPROVE NMFS’S INTEGRATION OF EQUITY IN MANAGEMENT

Recent work on equity supports the development of a comprehensive strategy for incorporating equity into management, tailored within regions. Arguably, devolving management processes and decisions to the regional level positions NMFS ahead of other organizations that lack the power at lower scales.

A starting point would be an evaluation of current decision-making processes in both fisheries governance and NMFS operations. It would be useful to assess recognitional equity—meaning who is represented and what views are represented—in decision-making processes related to benefits, and procedural equity—how those processes are structured. A regional fishery management council and its related advisory and decision-making structures could serve as a helpful case study. Such a study would be both tractable and informative. Similarly, it could be useful to assess to what degree participatory (public and otherwise) processes consider and integrate questions of both recognitional and procedural equity, although this would expand substantially the scope of an initial case study.

A case study of a regional council would likely identify a lack of representation and inadequate processes, suggesting a need to make progress in procedural and recognitional equity. As discussed previously, NMFS’s limited capacity constrains its ability to engage in advancing equity considerations. There are also barriers to groups participating in more holistic processes, ranging from costs to histories and cultures of distrust. The latter issue points to the need for NMFS staff to (1) articulate clear plans early on to assure participants their voices will be considered and (2) adopt new forms of outreach that acknowledge these past experiences. These barriers—especially those of time and monetary costs—would be addressed in part by actions to increase NMFS capacity and resources, as described in Recommendation 3-3. This could include NMFS supporting staff to work with and in communities or funding for a more diverse range of participants to travel and engage in management processes. For example, the location of the June meetings of the North Pacific Fishery Management Council rotates to smaller geographic communities.

Technological advances may also provide new opportunities. For example, although the COVID-19 pandemic created short-run challenges for fisheries and fisheries management, it brought about a shift to remote council meetings, which have continued to be livestreamed in some cases. Continuing with or adding remote participation options has the potential to reduce costs of participation and therefore make participation easier. However, unreliable and/or non-existent Internet access, lack of facility with technology, a lack of proficiency with English, and other factors could continue to serve as barriers to inclusion in formal processes.

While a shift toward a more inclusive approach to equity will take time and resources shorter-term and lower-cost changes may help begin to “move the needle.” NMFS can help to indicate its commitment to improving equity by identifying points in the management process that are inconsistent with policy and could be rethought and modified within a more comprehensive approach to equity. For example, this report highlights Stock Assessment and Fishery Evaluation reports for tracking of fishery outcomes and social impact assessments for proposed rulemakings as potential on-ramps to improving equity in fisheries. The committee also suggests that NMFS consider its own structures, composition, collaborative opportunities, and approaches to improve the capacity of NMFS staff at all points in the management process.

RECOMMENDATION 5-1: The National Marine Fisheries Service should continue its work on equity in the nation’s fisheries, and it should move beyond a focus on distributional outcomes associated with permit and quota holdings to a more multidimensional assessment of equity. This will require addressing a range of complex challenges that can be informed by existing programs, projects, and frameworks, but will not likely be achieved by minor adjustments to existing efforts. Addressing these challenges will, among other things, demand a contextually based, multidimensional approach and a considerable expansion of the social science capacity within the agency as well as the development of partnerships across a range of governmental and non-governmental sectors.

This page intentionally left blank.