Assessing Equity in the Distribution of Fisheries Management Benefits: Data and Information Availability (2024)

Chapter: 2 The National Marine Fisheries Service Mandate for Equity

2

The National Marine Fisheries Service Mandate for Equity

This chapter draws on current literature to highlight the importance of considering the multiple dimensions of equity. It introduces concepts of recognitional, procedural, and contextual dimensions of equity that should be considered in parallel to the distributional questions of equity related to permits and quota. The chapter begins with the concepts of both the subjects of and criteria for equity considerations, and then presents an understanding of the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) mandate for, and understanding of, equity as contained within the Magnuson-Stevens Act (MSA) and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), as well as recent executive orders, strategy documents, and other instruments. Finally, the chapter provides some examples of how these concepts have been conceptualized and applied in fisheries management.

As a whole, this chapter serves as a foundation for the following chapters, providing both an explanation of terms and the committee’s rationale for the scope of the report. While the word equity does not appear in the statement of task, it is central to the context within which NMFS requested this study. The importance of centering equity in this report was made clear to the committee during the information-gathering meetings, including in presentations by the study sponsors.

WHAT IS EQUITY?

Equity (and the related term justice1) is a multidimensional concept concerned broadly with fairness (Campbell et al., 2021). Although the focus of this report is equity, recent executive orders and strategy documents often link equity and justice. Chiefly, equity concerns (1) the “distribution of costs, responsibilities, rights, and benefits,” including distribution of noneconomic costs and benefits; (2) “the procedure by which decisions are made and who has a voice” in them; and (3) “recognition—acknowledgement of and respect for the equal status of distinct identities, histories,

___________________

1 While the terms are often used interchangeably, equity and justice emerged in different contexts (Dawson et al., 2018). As reviewed in Campbell et al. (2021), equity emerged as a concern in policy circles as something to be resolved through policy design. Environmental justice emerged external to and in opposition to policymaking bodies that were seen as responsible for environmental harms to low-income communities and communities of color.

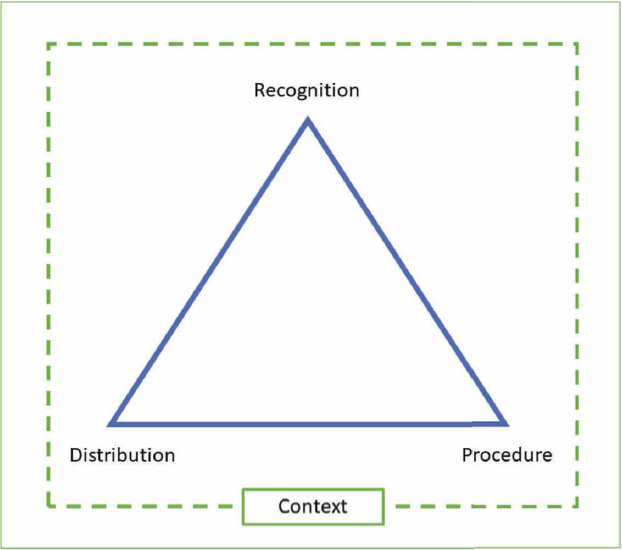

values, and interests of different actors” (Friedman et al., 2018, p. 2). Visualizing these dimensions in relation to one another, the equity “triangle” (shown in Figure 2-1) is embedded in a contextual framework. Indeed, context is increasingly recognized as a fourth dimension of equity (Campbell et al., 2021). Contextual equity accounts for social, economic, political, cultural, and historical contexts that influence one’s ability to participate in decision-making, receive a fair share of benefits, and gain recognition (Pascual et al., 2014; Wells et al., 2021). No single dimension is sufficient in itself to represent equity: each is a necessary but insufficient condition in an equitable system.

Distribution

In the context of resource management, distributional equity is primarily concerned with who enjoys the benefits or pay the costs of interventions (Shreckenberg et al., 2016). These concerns arise at different scales and within groups (e.g., by race, class, gender, caste, or ethnicity within local communities) that are subject to equity concerns. While no single measure of distributional equity exists, Box 2-1 summarizes some of the criteria and principles that can be used to assess distributional equity. The variety of criteria, all of which are “equally justifiable both in ethical and operative terms” (Pascual et al., 2010), highlights the challenges of achieving distributional equity; what is deemed “fair” by fisheries managers may not be perceived as fair to all or a subset of fishers or to others affected by fishery management decisions. Additionally, fisheries management often involves trade-offs among different kinds of benefits and costs as perceived among different groups according to different values (e.g., fish as food, versus a recreational resource, versus an income generator, versus carbon storage; Campbell et al., 2021). Within the environmental field, when equity has been assessed, distribution of benefits and costs has received most attention. The focus on distribution is challenged by many authors (e.g., Dawson et al., 2018), who argue that procedural

SOURCES: Adapted from Franks and Schreckenberg (2016) and Schreckenberg et al. (2016). See McDermott et al. (2013) and Pascual et al. (2014) for alternative visualizations.

and/or recognitional equity are a prerequisite to multiple, culturally informed understandings of distributional equity (Campbell et al., 2021).

Recognition

Recognitional equity aims to diversify and legitimize different inputs into decision-making, by recognizing the rights, knowledge, values, interests, and priorities of different groups. For example, recognition of Indigenous rights and knowledge systems, encompassing, Indigenous Knowledge and Traditional Knowledge, is receiving renewed attention in federal research, policy, and decision-making (see, e.g., White House [2022], and Executive Order 13175 [White House, 2000] on strengthening Tribal consultation processes). Indigenous Knowledge and diverse ways of knowing have been central to the concept and development of co-management regimes, even though this has seldom been framed as an equity issue (e.g., Hoefnagel et al., 2006; NPFMC, 2023). Indigenous Peoples have deep knowledge of ecosystems (Martin et al., 2016) and worldviews and cultural values that historically have been under-accounted for and marginalized in fishery management. Furthermore, Indigenous worldviews and livelihood practices may provide approaches for more sustainable and just ways of living in the world (Dawson et al., 2018, 2021). As another example, gendered knowledge of the environment or the local knowledge of particular resource users, such as active commercial, subsistence, or recreational fishermen who may be non-Indigenous are also recognized as legitimate and valuable forms of knowledge that should be taken into account in fishery management and decision-making (NPFMC, 2023; see also Belisle et al., 2018). Recognitional equity can also involve acknowledging existing structures that may favor particular types of information in decision-making—for example, the management process itself can prioritize certain forms of data while discounting others (e.g., quantitative versus qualitative; Martin et al., 2016; Schreckenberg et al., 2016). Thus, recognitional equity is intertwined with and has implications for procedural equity, which is discussed next.

Procedure

Procedural equity attends to processes of knowledge collection, decision-making, and management. It is concerned with who is involved in decision-making and how decisions are made. Who decides the criteria for assessing a “fair” distribution? How is the value of a given resource or a particular outcome assessed? What kinds of knowledge are most relevant? Procedural equity draws broadly on principles or best practices for the inclusive and effective participation of all relevant individuals and groups. These questions and principles make procedural equity challenging to implement and achieve in practice, given that the processes for identifying those who should be included, and for structuring engagement, are themselves power laden (Martin et al., 2016). Of particular concern has been the need to identify those who traditionally have not been involved in such processes, or who have been intentionally excluded from past management decisions. In our deliberations, the committee encountered challenges of identifying and considering “who is not in the room” in multiple ways and on multiple occasions.

Even where an inclusive and exhaustive list of individuals and groups is identified, each likely has unequal capacities and resources to participate. Participation is often influenced by broader cultural and social norms and is costly to participants (Cooke and Kothari, 2001; Cornwall, 2008). Participation is sometimes used to “convince” people of the value of particular activities rather than to recognize the legitimacy and value of their input. Thus, poorly designed or intended efforts to encourage participation can increase inequity (Campbell et al., 2021).

Context

Context is increasingly recognized as the fourth dimension of equity, shaping the possibilities for achieving distributional, recognitional, and procedural equity (Campbell et al., 2021). Efforts to realize equity or mediate inequities do not occur against a blank slate, but rather are shaped by both prior and current social, economic, environmental, cultural, and political conditions (e.g., Gurney et al., 2021; Lau et al., 2021; Martin et al., 2016; Sikor et al., 2014; Zafra-Calvo et al., 2017). Context can shape understandings of equity, including its definition, which dimensions are deemed most important, and how subjects of equity are imagined (e.g., individuals, fleets, communities, non-human entities).

Researchers disagree about which component of equity is most important, in the sense of being prerequisite to the others, but this too may be mediated by context. Indeed, the committee would argue that questions regarding the relative importance of the different dimensions of equity are ill-posed. It is abundantly clear from the literature that all four dimensions are important and linked. Single dimensions of equity are neither sufficient nor solely necessary for a complete assessment of equity.

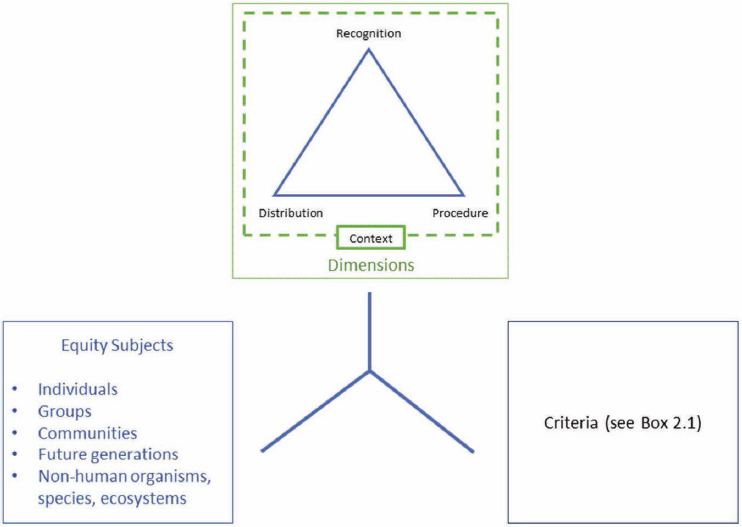

CRITERIA AND SUBJECTS

The four dimensions of equity identified above do not, in and of themselves, define an equitable system. Rather it is how these four dimensions of equity are integrated within a system that identifies both the criteria for how the dimensions of equity are defined and applied, and the “subjects” in the system that is important (Figure 2-2).

Equity is not a universally understood social good to be delivered through well-designed policy. Instead, equity is political and often emerges as a policy priority based on concerns about inequity. As noted by Campbell et al. (2021, emphasis in original), “Pursuing equity often involves mediating competing claims about distribution, recognition, and procedure, among diverse ‘subjects’ and according to varied ‘criteria.’” Recognizing diverse equity subjects in a given context

SOURCE: Modified from Sikor (2013).

acknowledges that the distribution of benefits or costs is often a redistribution of an existing pool of goods, rather than the distribution of additional or new goods. Identifying the subjects of equity can be complex. The sustainable development literature draws attention to equity concerns among intra- and inter-generational subjects (Baron, 2021). Intergenerational inequities have also been a focal area in the fisheries literature (Donkersloot and Carothers, 2016; Ringer et al., 2018; Sumaila, 2004: Sumaila and Walters, 2005). Sikor et al. (2014) identify subjects as individuals and groups of people who have rights or bear responsibilities, have a role in decision-making or are deserving of recognition and respect from others involved in the process (e.g., Tribal Nations). Some argue that equity should be extended to non-human organisms or nature more broadly (Hardin-Davies et al., 2020).

NMFS MANDATE FOR EQUITY

Several statutes, instruments, and documents related to environmental equity shape the policy and regulatory arena in which NMFS operates. The committee considered a range of authorities including legislation (such as the MSA); codified rules; and guidelines that flow from relevant statutes, regulations (e.g., Code of Federal Regulations), executive orders, and key departmental- and agency-level policy directives and strategies (from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and other relevant agencies, such as the Environmental Protection Agency). A partial list of authorities is provided in Box 2-2. In particular, the committee sought to ground its work, to the extent possible, in the MSA, as it carries legal weight and is supported by case law. It is increasingly common to align questions of equity and justice. This is particularly true in the most recent executive orders on strengthening Tribal consultation processes and racial equity, and in agency documents, such as the NMFS Equity and Environmental Justice Strategy (EEJS) (NMFS, 2023b).

This section maps the policy arena onto the conceptual framework for equity derived from the literature, with the goal of comparing NMFS’s stated conceptualization of, and perceived mandate

for, equity and environmental justice in the fisheries context with the conceptualizations and critical issues raised in the wider academic literature. The committee notes three caveats: First, this is not an attempt to evaluate what NMFS has done or currently does; rather, it provides a basis for the analysis in subsequent chapters. Second, the committee is not attempting to be comprehensive and map all possible instruments (or all aspects of each instrument) onto this conceptual framework. Rather, it provides examples from key instruments, often definitions, that illustrate a fit with the various components in the framework. Third, while we sometimes associate specific instruments with particular aspects of the conceptual framework, many instruments fit with more than one aspect.

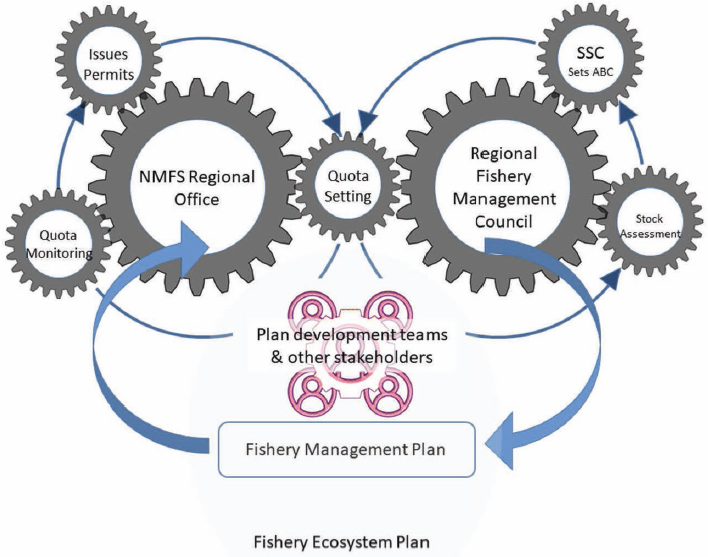

The MSA defines the framework for management of federal fisheries (Figure 2-3) and establishes a regional approach to fisheries management through eight regional fishery management councils. Each council is required to manage the fisheries within federal waters in its jurisdiction to meet the 10 principles that the MSA codifies as National Standards (Box 2-3). Each is accompanied by supporting guidance for its implementation. In general, the MSA requires that federal fisher-

ies are managed under an approved fishery management plan. Plans can be for single or multiple species and are overseen by regional fishery management councils. Each fishery management plan must comply with the National Standards. Four of the 8 Regional Fishery Management Councils have released Fishery Ecosystem Plans, which seek to ensure management across fisheries is coordinated to achieve sustainability goals for the ecosystem.

Each fishery management plan establishes the permit structure, what rights are associated with a permit, the nature of fishery reference points used to set the quota (e.g., allowable biological catch and annual catch limit, as defined in National Standard 1), and how the fishery will operate. Once established, permits are approved by NMFS regional fishery offices, and quota are set by the relevant regional fishery management council using the best scientific information available, as required in National Standard 2.

The MSA includes a number of requirements and references relevant to the study statement of task and equity in fisheries more generally. Several requirements relate to the “fair and equitable” distribution of benefits (e.g., National Standard 4), as well as the economics and social and cultural framework of a fishery. Collectively, these lay important groundwork for thinking about both fishery benefits broadly and the dimensions and subjects of equity (introduced above and elaborated on below) in the specific context of federal fisheries, and potential categories of information as identified in the statement of task.

National Standard 4 is perhaps the most obviously connected to equity and requires the fair and equitable allocation of fishing privileges, including limiting a particular individual, corporation, or other entity from acquiring an excessive share of such privileges.2 Equity considerations

NOTES: The upper half of the figure focuses the administration and setting of quota. The lower portion focuses on the establishment, allocation, and administration of permits via fishery management plans. ABC = allowable biological catch; NMFS = National Marine Fisheries Service; SSC = Science and Statistical Committee.

___________________

2 16 U.S.C. § 1851(a)(4).

outlined in this standard raise challenging questions, especially when the current conditions represent significant restrictions on participation compared with the past (Turner et al., 2008)—or when approaches to maximizing overall benefits further displace marginalized people or exclude local communities from pursuing future options (Adams et al., 2004; Sikor et al., 2014). This tension may be especially pronounced as NMFS works to better address inequities associated with underserved communities (see below), as the need to consider “present participants and coastal communities” in allocation decisions could affect considerations of equity and environmental justice if past allocations were inequitable. On the other hand, guidance3 associated with National Standard 4 states:

An allocation of fishing privileges may impose a hardship on one group if it is outweighed by the total benefits received by another group or groups. An allocation need not preserve the status quo in the fishery to qualify as “fair and equitable,” if a restructuring of fishing privileges would maximize overall benefits. The Council should make an initial estimate of the relative benefits and hardships imposed by the allocation, and compare its consequences with those of alternative allocation schemes, including the status quo. Where relevant, judicial guidance and government policy concerning the rights of treaty Indians and aboriginal Americans must be considered in determining whether an allocation is fair and equitable.4

The NMFS EEJS acknowledges the above tension, noting that “considerations [about resource allocations] could include assessment of impacts and benefits to underserved communities and prioritization of actions that benefit or correct a disparity among communities” (NMFS, 2023b).

National Standards 1, 2, and 8 are also pertinent to the committee’s work. National Standard 1 (Optimum Yield) requires managers to avoid overfishing. Technical guidance for National Standard 1 includes, for example, aims to achieve the “greatest benefits to the nation” and refers to myriad fishery benefits, including those that are difficult to quantify, such as enjoyment gained from recreational fishing, preservation of a way of life, and the cultural place of subsistence fishing. National Standard 1 also identifies several social factors relevant to an assessment of optimum yield including proportions of affected minority and low-income groups. NS1 objectives are stated simply, without any modification, whereas most of the other NSs have contingent elements.

National Standard 2 (Best Scientific Information Available) allows inclusion of “pertinent economic, social, community, and ecological information,” including evaluation of ethnographic and qualitative data, and local and Traditional Knowledge. Finally, National Standard 8 requires taking into account “the importance of fishery resources to fishing communities ... to (1) Provide for the sustained participation of such communities; and (2) To the extent practicable, minimize adverse economic impacts on such communities.”5 Stoll and Holliday (2014) note that direct allocations to communities were authorized under Section 303A “appear to have been driven by Congress’ interest in supporting small-scale and community-based operations.”

The committee notes that the assessment of social impacts, including equity concerns, is central to several executive orders, which are listed in Box 2-2, and required under the MSA as well as NEPA (Clay and Colburn, 2020). For example, Executive Order 12898 emphasizes that the NEPA review process can and should be used to promote environmental justice. Furthermore, two additional government guidance documents are relevant to the consideration of environmental justice: federal guidance from the White House Council on Environmental Quality on Indigenous Knowledge and the Department of Commerce Environmental Justice Strategy.

___________________

3 The committee recognizes that revisions to the guidance documents for some national standards, including National Standard 4, are underway. The committee is aware of the Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking that was issued in May 2023 (88 F.R. 30934), but for the purposes of this report relied on the existing guidance.

4 50 CFR § 600.325 (c)(3)(i)(B).

5 50 CFR § 600.345(a).

Both the MSA and NEPA require meaningful participation in decision-making. For example, the MSA directs councils to “conduct public hearings, at appropriate times and in appropriate locations in the geographical area concerned, so as to allow all interested persons an opportunity to be heard in the development of fishery management plans and amendments to such plans, and with respect to the administration and implementation of the provisions of this Act.”6 The MSA also requires that, with limited exceptions, council meetings are open to the public for participation.7

The NMFS EEJS describes a wide variety of benefits that NMFS delivers, including permits and resource allocations, as well as other benefits, such as direct investments, data and decision-making tools, disaster assistance, and grant opportunities. The document also states NMFS’s intention to make these benefits accessible to underserved communities and to advance racial equity and provide economic opportunities to these communities. The NMFS EEJS identifies underserved communities as a central subject of equity concerns, describing them as sharing either a geographic location or “characteristics, history, or identity.” Executive Orders 12898 and 14008 reference similar and overlapping terms such as minority and low-income communities and/or disadvantaged communities. With respect to underserved communities, the NMFS EEJS states (NMFS, 2023b):

Underserved communities refer to communities that have been systematically denied a full opportunity to participate in aspects of economic, social, and civic life. These include geographic communities as well as populations sharing a particular characteristic, history, or identity.... Specific to the fisheries context, underserved groups within fishing communities may include, for example, subsistence fishery participants and their dependents, fishing vessel crews, and fish processor and distribution workers. Finally, territorial and commonwealth communities in American Samoa, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands may also be categorized as underserved. Underserved communities vary by region, and by the barriers they face. Furthermore, many of these community categories intersect. Hence identification of and meaningful involvement with underserved communities will be regionally specific and an ongoing process that will require long-term commitment.

In addition to geography, the definition provided above focuses on “shared characteristics” of individuals in various groups, including demographic characteristics such as ethnic and racial categories, religion, sexual orientation, gender, and disabilities. conditions (e.g., low income, high or persistent poverty) in which individuals live and characteristics (e.g., urban, rural) of their location. Although they are included in this definition of underserved, Tribal Nations and citizens bear unique historical and contemporary harms related to colonization; they also have a unique political status as sovereign nations.

The NOAA EEJS further notes that (1) underserved communities may include not only fishery participants, but also their dependents, crew, and processing and distribution workers (this is consistent with requirements in National Standard 8); (2) underserved community characteristics vary regionally and the categories intersect; and (3) the phrase “have been systematically denied” is utilized and consistent with phrasing in other policy instruments that recognize “being underserved” as a historical process, and cannot be understood solely as a present condition.

Additionally, the NMFS EEJS notes that several executive orders point to the importance of both recognitional and procedural equity. This includes the “meaningful engagement” of underserved communities. For example, the NMFS EEJS notes, Executive Order 14096 seeks to advance environmental justice by calling for “meaningful engagement and collaboration with underserved and overburdened communities to address the adverse [environmental] conditions they experience and ensure they do not face additional disproportionate burdens or underinvestment.” Likewise,

___________________

6 16 U.S.C. § 1852(h)(3).

7 16 U.S.C. § 1852(i)(2)(a).

Executive Orders 13985 and 14091 both define equity in terms that clearly have procedural elements (italicized emphasis added), stating that equity is:

who belong to underserved communities that have been denied such treatment, such as Black, Latino, and Indigenous and Native American persons, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and other persons of color; members of religious minorities; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) persons; persons with disabilities; persons who live in rural areas; and persons otherwise adversely affected by persistent poverty or inequity.

The NMFS EEJS defines recognitional justice as “the acknowledgement of and respect for pre-existing governance arrangements as well as the distinct rights, worldviews, knowledge, needs, livelihoods, histories, and cultures of different groups in decisions” (NMFS, 2023b). However, the document does little to define which groups should be “acknowledged and respected” beyond those identified as members of “underserved communities.”

The one prominent exception is Tribal Nations and Indigenous Peoples—particularly, the importance of Traditional Knowledge and Indigenous Knowledge. For example, in 2022, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and Council on Environmental Quality issued its first-ever federal guidance on Indigenous Knowledge, recognizing it as distinct from local knowledge and encompassing more than Traditional Ecological Knowledge and noting that it is an “important body of knowledge that contributes to the scientific, technical, social, and economic advancements of the United States and to our collective understanding of the natural world” and relates this knowledge directly to federal research, policy, and decision-making.

Local knowledge and Traditional Knowledge are also included in National Standard 2, which requires that the “best scientific information available” (BSIA) be used in support of decision-making. Specifically, the Code of Federal Regulations guidelines state that “relevant local and Traditional Knowledge (e.g., fishermen’s empirical knowledge about the behavior and distribution of fish stocks) should be obtained, where appropriate, and considered when evaluating the BSIA.”8 Recent White House guidance cited above and work undertaken in the North Pacific is useful here to understanding important differences between local knowledge and Indigenous or Traditional Knowledge and how these knowledge systems can be meaningfully and appropriately included in fishery management and decision-making processes (NPFMC, 2023).

Tribal Nations and Indigenous Peoples

The importance of procedural equity vis-à-vis Indigenous Peoples is highlighted not only as members of underserved communities, but also as members of sovereign Tribal Nations with particular political status in the United States that have been greatly harmed by various historical and ongoing processes of assimilation and suppression. In addition to the NMFS EEJS, several recent executive orders, Presidential Memorandums, and related policy directives reaffirm the federal government’s trust responsibility to federally recognized Tribes, to address past harms, and make clear that the impacts of federal fisheries policy on Tribes requires additional and explicit consideration beyond NEPA social and environmental impact analyses and MSA requirements (see, e.g., example Executive Order 13175, Presidential Memorandum of November 5, 2009 [Tribal Consultation], Presidential Memorandum of January 26, 2021 [Tribal Consultation and Strengthening Nation-to-Nation Relationships]). This raises important issues related to recognitional equity, including the issue of Tribes that are not federally recognized but maintain deep ancestral ties to coastal lands and fishing livelihoods. The committee recognizes that disputes related to federal recognition are

___________________

8 50 C.F.R. § 600.315(a)(6)(ii)(C).

beyond the purview of NMFS. Furthermore, Tribal citizens and Indigenous Peoples in the United States have been historically harmed and underserved as racial and ethnic groups (Carothers, 2011; Langdon, 2018). Recognizing that much work remains to be done to address past harms, some of which is beyond the role of NMFS, in the specific context of the committee’s statement of task, it is clear that a key challenge in better accounting for and addressing the impacts and participation of Tribal Nations and Indigenous Peoples in federal fisheries is the lack of data and systematic data collection to identify, understand, and account for how Tribal Nations and Indigenous communities rely on, participate in, and are affected by federal fisheries decision-making.

EXAMPLES OF EQUITY CONSIDERATIONS IN FISHERIES

The global fisheries and marine policy literature provides many useful examples of how the equity dimensions, subjects, criteria, and contexts introduced above have been conceptualized and applied in fisheries management. Examples highlighted below from the United States and other countries evidence different ways equity has been defined and considered in fisheries. This brief summary lays the foundation for Chapters 3 and 4, which discuss relevant categories of information and data needs.

In many limited access fisheries, criteria for identifying who is eligible to receive a permit or quota in a fishery depends on the specific program objectives and definitions of equity. Catch history or landings thresholds (often based on a narrow set of qualifying years) are perhaps the most common criteria associated with initial allocations. Other examples include criteria for identifying and ranking hardship, designed to favor participation among those with limited economic alternatives (e.g., Alaska’s Limited Entry System) and/or adjacency to the resource, intended to support local communities with high poverty rates (e.g., Western Alaska Community Development Quota Program; see also Foley et al., 2013 and Foley et al., 2015).

Provisions to existing programs in and beyond the United States have also developed criteria intended to address equity objectives in fisheries. These include age requirements (e.g., Norway’s Recruitment Quota is available only to fishermen under the age of 35), as well as rural, small-scale, and Indigenous provisions intended to revitalize fleets, communities, and regions that have fared poorly under limited access management programs (Chambers, 2016; Cullenberg, 2016; Cullenberg et al., 2017; Eythórsson, 2016; Langdon, 2008; Stoll and Holliday, 2014).

Impacts documented among particular groups and communities have informed many of the federal fishery mandates and policy directives summarized above, which draw attention to particular equity “subjects,” including crew and future generations; rural, local, small-scale fishermen; and/or low-income communities, shoreside labor associated with processing and distribution; and Tribal Nations and Indigenous Peoples. The emphasis on underserved communities adds additional complexity to the analysis of impacts.

Questions related to who is eligible to receive fishery benefits and the criteria selected to determine and evaluate what constitutes a fair distribution of fishery benefits is beyond the scope of this report. Asking and answering these questions will involve confronting multiple forms of power and the uneven power relations that can shape resource management and access. Power dynamics in fisheries and fishery management processes often result in negative impacts to less powerful segments of a fishery (Olson, 2011). This includes not only the ways in which procedural and recognitional (in)equities can contribute to enduring distributional effects that are difficult to mitigate once implemented (Carothers, 2010, 2011; Cullenberg et al., 2017; Krupa et al., 2018, 2020; Langdon, 2008; Pinkerton and Edwards, 2009), but also the ways in which distributional inequities can lead to procedural inequities and concentration of power and other forms of control (e.g., Chambers et al., 2017; Silver and Stoll, 2022).

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATION

The committee offers the following five findings and one recommendation derived directly from the material in this chapter.

FINDING 2-1: Equity is multidimensional and is more likely to be realized through an approach that accounts for each of the dimensions: distributional, procedural, recognitional, and contextual.

FINDING 2-2: Criteria or principles for assessing distributional equity vary, and there “is no rational way to prefer, a priori, one fairness criterion over another” (Pascual et al., 2010, p. 1239). Ideas of equity vary and are often culturally embedded. Attention to procedural, recognitional, and contextual equity can support the identification of criteria that may be acceptable to a broader range of stakeholders.

FINDING 2-3: Existing authority granted to NMFS by the MSA, the National Standards, NEPA, executive orders, and other instruments provides the agency with a clear mandate for a multidimensional and contextual approach to centering equity in its work.

FINDING 2-4: The distribution of benefits (including those derived from permits and quota) currently appears focused on particular individuals and groups, including sectoral allocations; historic participation; fishing communities; and in some cases, Indigenous organizations. The equity considerations centered in the NMFS’s EEJS and recent executive orders, including the focus on “underserved communities,” can both complement and challenge current approaches.

FINDING 2-5: The fishery and marine policy literature provides numerous examples of how dimensions of equity interrelate and can inform future approaches to defining and accounting for equity in fisheries.

RECOMMENDATION 2-1: The National Marine Fisheries Service should develop and implement a contextual, place-based, and participatory approach to identifying and integrating multi-dimensional equity considerations into decision-making processes in ways that balance previous and more recent mandates. Outcomes of these processes should include, among other things, clear identification of the criteria for, and appropriate subjects of, equity considerations.

This page intentionally left blank.