Assessing Equity in the Distribution of Fisheries Management Benefits: Data and Information Availability (2024)

Chapter: 4 Beneficiaries of Fishery Management Decisions

4

Beneficiaries of Fishery Management Decisions

The previous chapter discussed the distribution of benefits of permit and quota holdings in commercial and for-hire fisheries, focusing most closely on the individuals who directly own or hold permits and quotas. Chapter 3 also explored the opportunities for and challenges to assessing the distribution of benefits in real-world fisheries for which data are less available.

Chapter 4 broadens the scope beyond permit and quota holders to consider the potential for benefits to flow to other groups. This more expansive view explores the current and potential flows of benefits. We define three common categories of beneficiaries. For each category, the chapter defines the beneficiaries, evaluates categories of benefits, assesses the data available, and reviews methods that may potentially expand the data available. First, the chapter considers traditional beneficiaries—those who do not hold permits or quotas but work on the water, namely crew and captains. Next, it considers shoreside businesses, and finally, it discusses how communities benefit from fishery management decisions.

The committee recognizes that this linear approach ignores contextual equity. It ignores the history of fisheries management. By focusing on these three well-defined, common groups of beneficiaries, this approach ignores others who might have once benefited or who could benefit in the future, or whom society might wish to see benefit were different fishery management decisions made. Therefore, the final section of this chapter introduces the notion of potential beneficiaries as an improved way of thinking about equity in fisheries management.

COMMON CATEGORIES OF BENEFICIARIES

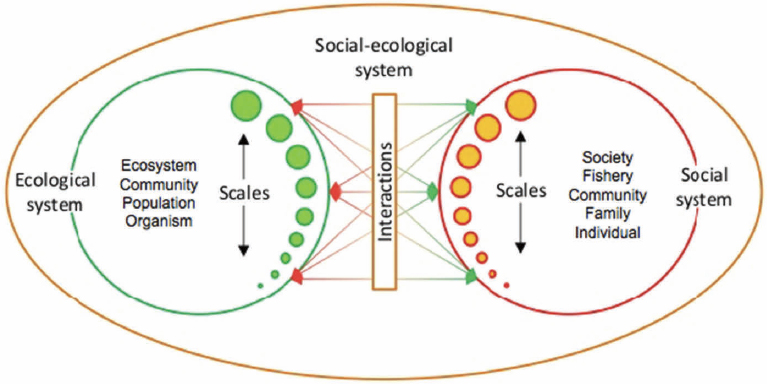

Fisheries directly support livelihoods, cultures, and economies. Many different groups of people are involved in and benefit from targeting, harvesting or catching-and-releasing, processing, selling, and consuming fish. Fisheries represent complex, interconnected social-ecological systems and it is important to recognize that benefits accrue at many scales from individuals to societies (Figure 4-1; Pomeroy et al., 2018). For individuals, fishing can represent identities and contribute to life and occupational satisfaction (Pollnac and Poggie, 2008; Pollnac et al., 2001). Scaling up to communities, fishing shapes local cultures, traditions, and livelihoods. At broader society levels,

SOURCES: Pomeroy et al. (2018), adapted from Martin et al. (2015).

fisheries contribute to both regional and national economies and food security. Likewise, while many facets of society are interested in fisheries, the level of engagement or reliance is highly variability and underpins the importance of understanding how and to whom benefits are distributed.

Beneficiaries are individuals or groups of people who do or may benefit directly from using, enjoying, consuming, or interacting with the environment and natural resources (Landers et al., 2013; Sharpe et al., 2020). The concept and terminology of beneficiaries provide a link between the language in the Magnuson-Stevens Act (MSA)—which is focused on benefits to the nation and is reflected in the Equity and Environmental Justice Strategy (EEJS) of the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS)—and other equity-based work focused on “populations sharing a particular characteristic, history, or identity” or are a subject of equity along another dimension (NMFS, 2023b).

Those beneficiaries in the fishery social-ecological system not holding permits or quota may be grouped in many ways, most commonly by sector (recreational, commercial, charter, subsistence), target species, gear type, or geography. For example, the “for-hire sector” means those beneficiaries who take paying clients fishing for sport or pleasure. Fisheries beneficiaries are often grouped by fishing characteristics, including their participation in specific fisheries (e.g., groundfish, shrimp, scallop) by areas and/or gear types (e.g., pelagic longline, trawler). The MSA is comprehensive and holistic in its view of fisheries. Included explicitly in the legislation and in the National Standards (see Box 2-3 in Chapter 2) are shore-based industries and subsistence fisheries. Fishing communities are another important and explicitly recognized group. National Standard 8 focuses explicitly on place-based fishing communities. However, as discussed extensively in Chapter 3, the place-based approach to fishing communities is limited, including the potential need to specific historically marginalized or underserved groups.

The following sections consider three broad and often overlapping groups of beneficiaries in fisheries, beyond permit and quota holders, that receive benefits stemming directly from fishery management decisions.

Crew

Definition

Crew are essential fishery beneficiaries and highly impacted by management decisions. Crew typically include non-owner captains, deckhands, and mates. Crew may also include other specialized roles (e.g., engineers, cooks).

Benefits

Crew receive both monetary and nonmonetary benefits from participating in fisheries. In many fisheries, crew often operate under a lay system in which they are paid a portion or share of net revenues when catches are sold (Acheson, 1981). Historically, working on fishing boats as crew has also provided an entry point for new careers in fisheries. However, the increasing start-up costs and capital required for fishing have severely impaired this apprenticeship-type model and impede upward mobility in fisheries (Ringer et al., 2018; Szymkowiak et al., 2022; see also Pinkerton, 2013, regarding the lay-up system in fisheries in British Columbia, Canada).

A number of studies have focused on how crew are impacted when fisheries transition to catch shares due to well-documented consolidation trends along with distributional and intergenerational inequities, and the subsequent creation of high barriers to entry (Carothers et al., 2015; Knapp, 2006; Knapp and Lowe, 2007; Olson, 2011; Pinkerton, 2014). While much of this literature characterizes the negative impacts on crew, including livelihoods, opportunities, and status, there are counter-examples where crew jobs remained constant and some measures of renumeration increased (Abbott et al., 2010). Some crew positions may be paid salaries or wages, in part due to the longer fishing seasons (Olson, 2011). Crew shares are not always equal splits, as individuals with greater experience or specialized skills (e.g., mechanic) or those are captains typically receive higher earnings (Olson, 2011). Instead of shares of landed fish, crew on for-hire vessels often supplement their wages in tips or gratuities from customers. Therefore, crew of for-hire vessels are most heavily impacted by the number of days, trips, and customers.

Crew also receive important non-monetary benefits as participants in fisheries. Holland et al. (2020) demonstrate the importance of job satisfaction, social capital, and identity as drivers of participation in West Coast fisheries (Holland et al., 2020). These factors often lead to individuals choosing to participate in fisheries, despite the higher income volatility and risk inherent in going to sea compared with other jobs (Holland et al., 2020). In some fisheries, crew are often relatives or children of vessel owners and captains providing a pathway to multigenerational participation. In other cases, crew positions can provide broad access to entry-level careers in fisheries, which is exemplified by the relative high proportion of crew with a high school diploma or less formal education (Henry and Olson, 2014). Crew positions can also include opportunities for individuals with limited employment options due to immigration or visa status. However, several recent studies have highlighted the major challenges facing crew and the fisheries businesses that rely on them. Along the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic coasts, recent surveys have revealed an aging fleet of crew with very few new entrants (Cutler et al., 2022). Studies of Vietnamese fishing fleets in the southeast have described the challenges of language isolation, including those between fishing crew and fisheries management and observers (Schewe and Dutton, 2018).

Data and Methodology

Data on crew in federal fisheries come mainly from surveys of crew conducted in different regions. In 2012–2013, in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions, the Northeast Fisheries Science Center (NEFSC) conducted a multiwave Socio-Economic Survey of Hired Captains and Crew

in New England and Mid-Atlantic Commercial Fisheries. In its first iteration, the survey sought a random sample of crew from ports from Maine to North Carolina. Participation in the surveys was voluntary. The survey interviewed 400 crew on the dock. Respondents provided data on basic demographic information, the principal fisheries in which the crew were engaged, and the principal ports at which catches were landed (Henry and Olson, 2014). The survey also collected data on well-being (including financial viability), social capital, and job satisfaction. This survey found that 60 percent of respondents had at least a high school diploma, and 85 percent identified as White. However, the number of self-identified ethnic groups reflected more diverse ethnic heritages (Henry and Olson, 2014). Crew member ages ranged from 16 to 75 years, with an average age that varied by fishery (Henry and Olson, 2014). The survey was repeated in 2018–2019, with a third wave ongoing in 2023. A further 377 crew members were interviewed in the 2018–2019 survey, responding to largely similar questions. In combination, these data begin to provide a time series of broad demographic patterns in crew and nonowner captains in the Northeast.

The State of Alaska offers one of the most comprehensive sources of which the committee is aware of information related to crew (see, e.g., Szymkowiak et al., 2022). Alaska requires a crew member license for any individual who directly or indirectly participates in a commercial fishing operation (e.g., engineers, cooks, vessel maintenance, gear work). The crew license, which can be purchased annually online and in person, collects information including full legal name, physical and mailing address, gender, date of birth, state residency (and length of residency), and state-issued driver’s license number (if applicable). A Social Security number (or temporary Social Security number for non-U.S. citizens) is also required for crew over 16 years of age. The State of Alaska annually publishes license statistics, but these are limited to quantity sold and cost data on Alaska resident versus nonresident crew license purchases. The main database provides only a measure of an intent to fish; detailed information on actual crew participation and behavior is generally unavailable. The exception is the Economic Development Reports (EDR) fleets in federal fisheries, which require crew permit reporting. Although an advantage of this database is that the coverage is complete, the information collected does not include information on most of the characteristics identified within NMFS’s EEJS.

Systematic knowledge of the monetary benefits of serving as crew in the harvesting sector is relatively limited. The Northeast survey discussed earlier asks questions about income levels by fishery, and data indicate substantial differences among fishery sectors in that region. By the end of 2023, NMFS will have data on trends in income in this region. In the North Pacific, the Crab EDR program is a mandatory data collection program. With the implementation of the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands (BSAI) Crab Rationalization Program, collection increased in frequency and requires participants to submit yearly information related to revenues and costs, including data on crew employment and earnings. This is another highly comprehensive data collection effort related to crew, as it is a complete census of a fishery and has longitudinal for following outcomes over time. Academic and NMFS researchers were able to link these data to other data, including landings, and used it to show that both the share and real value of vessel proceeds accruing to captains, crew, and vessel owners declined under the catch share regime (Abbott et al., 2022). Importantly in terms of relevance for assessing management outcomes, the program was in place prior to the management change to facilitate a before-and-after comparison.

Data on the benefits and costs of fishery management decisions on crew are important. The crew survey conducted in the Northeast region is a high-quality example of one possible approach to collecting data to characterize how the flow of benefits to crew is affected by management decisions related to permits and quotas. The committee recognizes the benefits of expanding this survey to other regions and applauds the use of power analysis in the design of the second and third Northeast crew surveys. However, the relatively small sample size, of approximately 400 sampled out of approximately 21,000 potential crew (~2 percent) may be insufficient to allow reliable inferences

on only the coarsest of patterns. The committee was intrigued with the potential power of a crew registry, such as that operated in the State of Alaska, to serve as a sampling frame for improving the design of crew surveys, even with the noted weakness that the registry is only an indication of intention to crew. Longitudinal crew panels may be another way of providing important information on patterns of participation and benefits. Future studies of crew may also be informed by recent studies on the agricultural, landscaping, and other “day laborer” scenarios, where informal employment arrangements are commonplace and often involve immigrant (e.g., Galemba, 2021; Valdez et al., 2019).

The committee recognizes that there has been recent progress toward addressing unique data collection challenges for crew, including tailoring surveys and information programs toward specific fisheries contexts. For instance, the shrimp fishing fleet in Gulf of Mexico includes many Vietnamese and Hispanic/Latino fishermen, and the ongoing NOAA Crew Survey is being implemented in three languages (English, Spanish, Vietnamese). However, the committee also recognizes the remaining challenges inherent in collecting such data, including privacy concerns, respondents risking future employment by being seen providing information and concerns over how data may be shared across the federal government. There are several questions for NMFS to consider in deciding how to continue and or expand these efforts. What are the key questions to be addressed with the collected data? What spatial and temporal scale of data is required to address the key questions? For example, the 5-year frequency of the NEFSC crew survey is likely to be sufficient for identifying long-term trends. It may not however, be sufficiently resolved temporally to support the development of models of how fishery participants may respond to or have responded to management changes. If this is the goal, surveys conducted before and after significant changes in management would be desirable.

Processing and Distributing Sector

Definition

Shoreside facilities include processing and distributional networks that take landed fish to market. Fish processing involves transforming landed fish into seafood products that are ready for distribution or sale to consumers. This includes cleaning, gutting, fileting, portioning, cooking (e.g., smoking, steaming), and packaging. Fish processors are sometimes permit or quota recipients, particularly in vertically integrated fisheries, such as surfclam and squid in the Northeast. Distribution of fisheries products occurs through complex networks and supply chains that move fish from the point of capture or harvest to consumers. Distribution ranges from small, local delivery to air, train, and other high-tech pathways to global markets.

Benefits

Similar to fishing crew, individuals involved with shoreside facilities receive both monetary and nonmonetary benefits. Most fish processing jobs offer low pay, require long hours, and can be dangerous (Matheson et al., 2001; Bonlokke et al., 2019; Syron et al., 2019; Jiaranai et al., 2022). While jobs such as fish cutters and processors typically offer the lowest pay, some related occupations, such as safety and quality control inspectors, machine operators, and supervisors, offer higher wages. Fish processing jobs are highly dependent on the current status and management of supporting fisheries. For instance, when fish and shellfish landings declined along the Atlantic coast in the 1970s and 1980s, Maryland’s fish processing plants shed more than 1,000 jobs (Stull et al., 1995). Another important dimension of the processing sector is its interdependence with the harvesting sector and its susceptibility to change with management change. For an important example,

the location of processors can influence harvesting behavior through selection of delivery location (Birkenbach et al., 2022). On the other hand, the product and delivery timing can influence processor profitability. Examination of the West Coast Groundfish Trawl Catch Share Program by Guldin et al. (2018) suggests that changes, including consolidation of buyers and price, can occur post-catch share. Additionally, in fisheries that involve catcher-processor vessels, it is not uncommon for individuals to work as both crew and processors. It is worth noting that typical compensation systems tend to remain where crew are typically paid in shares and processing in wages (Olson, 2011). There are also important links between the processing sector and communities. Processing facilities and the people they employ are central to many fishing communities (Hall-Arber, 1996). Recognition of this linkage has led to calculation of a processing engagement indicator and a measure of the distribution of processed catch amongst Alaskan communities in the Annual Community Engagement and Participation Overview (ACEPO). In the southeast United States, fish processing plants have long relied on immigrant and temporary (i.e., H-2B visa) labor to fill the typically low paying processing jobs.

After processing, fish distributors provide the pathway for connecting wild-caught fish products to fish markets, restaurants, and international seafood brokers. Ethnographic research by anthropologists has long suggested that individuals working in distributing (e.g., lumpers) may be less socially or culturally tied to fishing, compared with harvest-related occupations (Hall-Arber, 1996). However, this is highly variable across fisheries and regions. In some fisheries, distribution occurs through standard temperature-controlled distribution pathways that involve sophisticated logistics. However, in other fisheries, distribution follows a “catch to table” model in which each step of the supply chain is conducted directly by the fishermen. Very little information is available on salaries or demographics to characterize fish distribution. Entry-level and typically lower-paying jobs include warehouse workers and local delivery drivers, whereas sales, supply chain managers, logistics coordinators, and food safety specialists typically earn more. It is important to note that many of these higher-paying jobs may be located at central distribution offices and not within fishing communities. Nonmonetary benefits of the processing and distribution sector relate most to providing seafood that supports consumer welfare (Costello et al., 2020). Fishery management decisions, including issuance of permit and the allocation of quota directly affect this non-monetary good (Costello et al., 2020).

Data and Methods

Very few studies have focused on the social, economic, or demographic dimensions of fish processing and distribution. The studies that exist are generally ethnographic studies. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) technical reports are available for some regions, although most are quite outdated. For instance, Bayou la Batre, Alabama, is among the more extensively profiled fishing communities where processing and distributing has been described in peer-reviewed literature and NOAA reports. One study reported approximately 24 processing plants, each employing an average of 30 workers, in a town of slightly more than 2,000 people—illustrating the importance of fisheries to the community (Petterson et al., 2006). This study also described the demographics of Bayou la Batre from the 1990 and 2000 censuses, including high racial and ethnic diversity, with a population that is 33 percent Asian and 20 percent Black or African American. Bayou la Batre also represents a fishing community with higher-than-average levels of language isolation; 16 percent of residents speak English less than very well. Collectively, these characteristics illustrate the importance of understanding local context for assessing and measuring equity in small, diverse fishing communities.

Previous NOAA Social Science reports have described several practical and logistical challenges for characterizing seafood processors and other shore-side businesses including the “Rule

of Three,” which requires a sample size of at least three per community to promote confidentiality (Petterson et al., 2006). Many fishing communities may have one or two processing plants that are critical to individuals and communities, yet reporting landings, employment, and other statistics is typically not permissible. For instance, if less than three dealers purchased or sold a fish species during a given year, the data associated with those landings typically would be confidential. While confidential data may be accessible to researchers through non-disclosure agreements, they are not generally available for public dashboards or discussions.

Communities

Definition

The importance of communities as entities impacted by fisheries management and policy is identified explicitly in National Standard 8 of the MSA. This standard requires consideration of “sustained community participation” and “minimization of adverse economic impacts on fishing communities.” In defining fishing communities, National Standard 8 guidelines make a shared geographic location an explicit criterion and also provide a list of community members that extends beyond license holders and vessels owners. The term fishing community means a community that is substantially dependent on or substantially engaged in the harvest or processing of fishery resources to meet social and economic needs, and includes fishing vessel owners, operators and crew, as well as fish processors that are based in such communities. While there are many different definitions or ways of characterizing fishing communities, a unifying theme is the connectedness of fishing to many other aspects of the economy and culture leading to entities such as maritime museums, seafood markets, and service-related businesses tailored specifically to the needs of fisheries and other maritime businesses.

As noted in Chapter 2 there is a potential that a focus on current participants and fishing communities (see National Standards 4 and 8) could inhibit equity and environmental justice considerations when past decisions (including, presumably, allocations and licensing) serve to disadvantage underserved communities. On the other hand, National Standard 8 guidelines also state:

This standard does not constitute a basis for allocating resources to a specific fishing community nor for providing preferential treatment based on residence in a fishing community.1

Benefits

Communities obtain monetary and nonmonetary benefits that result from management decisions related to permit and quotas allocation. NMFS does not track well the flow of product once it leaves the dock, and thus connecting the economic benefits of permits and quotas to community benefits is a nontrivial problem. In addition to these monetary benefits, there are diverse nonmonetary benefits of permit and quota holdings in relation to fishing communities. Fishing communities are diverse, spanning from small artisanal communities in the Western Pacific to large industrial ports in the Northeast, and cultural identities are important across this spatial spectrum. The committee heard that in some communities, particularly in the Western Pacific, fishers achieve considerable standing and respect in the community by gifting fish either for others in the community as food security or for important community celebrations.

In some regions, communities can receive direct benefits from holding permits and/or quotas. Prominent examples of community-held quotas in Alaska include the Community Development

___________________

1 CFR § 600.345 (b)(2).

Quota (CDQ) Program in Western Alaska, discussed in Chapter 3, and the Community Quota Entity (CQE) Program. The CQE Program was implemented in 2005 to allow eligible communities in coastal Alaska to create entities authorized to purchase and hold halibut and sablefish quota shares. Direct allocations to fishing communities were also authorized in the 2007 MSA reauthorization, which includes language authorizing mechanisms for distributing fishing privileges to communities (see Sections 303A(c)(3) and (4) of the MSA, authorizing fishing community and regional fishery association entities). Beyond permit and quota holders, NMFS has a specific interest in (and obligation to consider) the effects of management actions on fishing communities more broadly.

Data and Methods

Considerable amounts of data are available related to monetary values that accrue in specific fishing communities (NMFS, 2023b). These estimates are based on the value of fish and shellfish landed in individual ports.

Earlier chapters highlight some of the substantial work that has been done to develop indicators of coastal community social vulnerability to better account for the community impacts of fishery management and policy (e.g., Colburn et al., 2016; Jepson and Colburn, 2013). These multivariate analyses integrate and synthesize data collected on thousands of communities from many coastal states. Fisheries data come from port-specific information, including number of permits and volume and sector distribution of landings, derived from vessel trip reports and port agents. These are combined with community-based data that rely heavily on data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. Additional community-level data on nonfederal sources were also included. A factor analysis was then used to derive indices related to measures of community reliance (i.e., dependence) on fishing (e.g., Colburn et al., 2016). NOAA’s Social Indicators website describes the indices as useful for both National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and MSA assessments, as well as the environmental justice concerns of Executive Order 12898 (NMFS, 2021). NOAA defines four key fisheries indicators (NMFS, 2021):

- Commercial fishing engagement measures the presence of commercial fishing through fishing activity as shown through permits, fish dealers, and vessel landings. A high rank indicates more engagement.

- Commercial fishing reliance measures the presence of commercial fishing in relation to the population size of a community through fishing activity. A high rank indicates more reliance.

- Recreational fishing engagement measures the presence of recreational fishing through fishing activity estimates. A high rank indicates more engagement.

- Recreational fishing reliance measures the presence of recreational fishing in relation to the population size of a community. A high rank indicates increased reliance.”

Beyond the fisheries focused indicators, NOAA’s Social Indicators include national-level indicators of social vulnerability. For instance, Personal Disruption is an index that reflects “the kinds of changes and circumstances that might affect a person’s ability to find work, propensity to be affected by crime, exposure to poverty, or personal circumstances affecting family life or educational level.” Population Composition is an index that “corresponds to the demographic makeup of a community including race, marital status, age, and ability to speak English”. These indicators have been used in environmental justice analyses and generally illustrate that fishing communities typically exhibit higher levels of poverty, vulnerable populations, and personal disruption (see Figure 3-2 in Chapter 3). While there are many potential management scenarios where such data could be useful, their direct consideration or influence on management decisions remains unclear.

Indicators of coastal community engagement have also been adapted for use in different regions. For example, the ACEPO presents “social and economic information for those communities substantially engaged in the commercial Fishery Management Plan (FMP) groundfish and crab fisheries in Alaska.”2 ACEPO reports are meant to support data needs related to National Standard 8 and respond to the North Pacific Fishery Management Council management objectives. The report is based on a mixed-method approach. The ACEPO includes an analysis of time-series data on landings to characterize community engagement and the concentration of catch in terms of harvesting and processing. It also contains qualitative deep dives into heavily engaged communities. Additionally, the ACEPO offers some information on the broader community context in which these fisheries exist. Specifically, it contains analysis of school enrollment and estimates of taxes collected. Although these community summaries provide some information beyond quota and permit holders, expanding updating these efforts could improve the responsiveness of these tools to support equity in fisheries management. First, this information needs to be available and current at the time of management decisions. Additionally, rather than characterizing a snapshot in time or a recent time series, which is typical, a richer understanding of equity requires presenting this information since fishery inception. Similar to the Southeast region, the North Pacific is moving in the direction of using webtools with its Human Dimensions Data Explorer,3 which could facilitate these types of extensions.

The committee appreciates the extensive analyses that the Agency has conducted to explore patterns of community dependence and resilience. The committee recognized specific limitations arise from grounding the Community Social Vulnerability Index (CSVI) and similar analyses in U.S. Census data. First is the issue of temporal granularity, as Census data are collected at 10-year intervals, which may or may not match important time scales for changes in fishing communities. This same issue would apply for any episodic data collection structure with a period that does not match well with the dynamics of social-ecological systems or the impacts of decision-making. Second, the data are aggregated and presented at the community level, reflecting an issue of spatial granularity. Census tract–level data can (arguably) be aggregated to identify, for example, levels of poverty, population composition, and personal disruption (the three indicators that comprise the environmental justice component in the CSVI toolkit) at the community level. However, it is not clear whether and how Census data can be disaggregated to assess differences (e.g., in the presence of underserved community members) within geographic communities (or within tracts, if those were made available). Third, the CSVI was not designed to assess the flow of benefits from fisheries, but rather to describe the composition of communities across various indicators. Thus, while the CSVI might indicate the sustained participation or vulnerability of a (geographic) fishing community over longer time scales, it is less able to describe the underserved communities within those fishing communities, or the fishing-related benefits they do or do not enjoy. Seeking alternative sources of community-specific information seems to be an important way of improving these indices to make them more responsive to potential patterns of change in fishing communities.

As NMFS seeks to expand its commitment to equity, one of its central challenges is the need to increase its capacity to design, conduct, and analyze structured or semistructured interview surveys to gain insights into important aspects of community identity, intergroup dynamics, and values. These surveys are complex instruments that vary in the amount of information that interviewees can introduce outside of the survey questions. In structured interviews, only information directly relevant to the questions is included, whereas in semistructured interviews, the interviewee can introduce other topics. These surveys have been used widely in social science research related to

___________________

2 See https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/alaska/socioeconomics/human-dimensions-fishing#community-information-for-annual-tac-determination:-acepo-and-social-indicators-for-coastal-communities.

3 See https://reports.psmfc.org/akfin/f?p=501:2000:12011482822315.

fisheries to capture and quantify fisher’s knowledge (e.g., Neis et al., 1999). Damiano et al. (2022) provides a recent example of the application of semistructured interviews in the for-hire fishery section in the South Atlantic region. Success in structured interviews requires development of trust between the interviewers and interviewees. This can often require a pattern of consistent engagement prior to the deployment of any survey instrument. Structured interview surveys also require considerable postsurvey analysis and synthesis to code the individual responses. This expertise can be developed either through increasing capacity within the agency (see Recommendation 3-3) or through partnerships with practitioners.

POTENTIAL BENEFICIARIES

The preceding sections consider common categories of beneficiaries, following a linear chain from seafood harvest to sale. This chain provides numerous monetary and nonmonetary benefits, although the specific benefits may vary along the chain. However, in considering the complete framework for equity described in Chapter 2, this simple linear chain of beneficiaries is clearly embedded within a contextual framework. Those who benefit today are but a portion of those who may have benefited from fisheries in the past, or who could benefit today, or even who society would wish to see benefit in the future from fish stocks as public trust resources. Thus, this section turns to potential beneficiaries—individuals, entities, or communities (geographic or sharing another common dimension) that have the potential to benefit from fisheries if the fisheries were managed differently.

Potential beneficiaries are not stakeholders. There are important differences between stakeholders and potential beneficiaries. Stakeholder is a general term for interested or affected individuals and groups. In fisheries, this may include group designations, such as recreational fisher, commercial fisher, environmental group, or fishery manager. In contrast, potential beneficiaries are groups of people who currently do or could receive benefits from fisheries management. While both stakeholder and potential beneficiary classifications provide a lens for considering how fisheries management affects people, the most important difference is how using the two terms may influence whether or not certain groups are considered. Crosman et al. (2022) state, “Equity comparisons framed around stakeholders are common, [but] can be problematic…. The term ‘stakeholders’ obscures differences in the basis and nature of claims between different groups. Specifically, the term diminishes customary, traditional, or treaty rights holders’ claims to a ‘stake’ rather than a sovereign right.” The term stakeholder has been increasingly criticized both for its impacts on Tribal citizens and Indigenous Peoples and for reinforcing hierarchal structures of management (Reed and Rudman, 2023). Connecting this back to the discussion in Chapter 2 on equity subjects, potential beneficiaries who lose access to or who are currently excluded from benefits of federal fisheries might then be considered subjects of inequities (e.g., federally recognized versus non-federally recognized tribes).

Although there are existing frameworks for characterizing potential beneficiaries in environmental management, there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Much more information is available to characterize stakeholders than beneficiaries. Importantly, this literature has a long history of emphasis on assessing equity among stakeholders, which makes transitioning toward information that characterizes potential beneficiaries straightforward. One of the earliest papers on stakeholder engagement described a “ladder of engagement” where each rung corresponds to an individual’s or groups’ potential power or influence (Arnstein, 1969). Mikalsen and Jentoft (2001) focus directly on fisheries, presenting both a potential framework and a Norwegian case study. Their work was originally framed with respect to stakeholders, and asked two key questions: (1) Who has a legitimate claim on the attention of managers? This question is largely framed to identify potential

beneficiaries. (2) Who is actually considered a beneficiary by managers? This question focuses on salience and recognition. Mikalsen and Jentoft’s framework identifies three criteria related to potential beneficiaries: urgency, power, and legitimacy. More recently, a paper by authors from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed a stakeholder prioritization framework (Sharpe et al., 2020), which was integrated in an EPA scoping tool for decision-making (Sharpe et al., 2021). The committee uses this framework to illustrate ten potential criteria, which are listed and defined in Table 4-1, with a key message being that a systematic approach to prioritize potential beneficiaries and their input is widely needed in fisheries decision-making. Notably, equity and environmental justice considerations are centrally positioned in the framework through three criteria. “Rights” accounts for individuals and groups who hold legal or other rights that might impact or be impacted by the decision. Fairness indicates whether or not excluding a group would lead to a perception of unfair decision-making. Lastly, and highly relevant for this report, Underrepresented / Underserved populations denotes whether or not a group includes such populations.

As described throughout this report, underrepresented or underserved populations can be characterized in many ways. For societal and federal workforce considerations, Executive Order 13985 directly provides many specific categories:

TABLE 4-1 An Example Scheme for Categorizing Potential Beneficiaries

| Stakeholder prioritization criteria | Definition |

|---|---|

| Level of interest | The amount of interest a stakeholder group has in the decision-making process or the decision outcome |

| Level of influence | The amount of influence a stakeholder group has over the decision-making process |

| Magnitude of impact | The degree of potential impact to the stakeholder group as a result of the decision |

| Probability of impact | The likelihood of potential impact to the stakeholder group as a result of the decision |

| Urgency/temporal immediacy | The degree to which a stakeholder group would like to see a decision made or an action taken |

| Proximity | How frequently a stakeholder group comes into contact with the environment for which a decision is being made |

| Economic interest | Whether a stakeholder group’s livelihoods or assets could be impacted by the decision outcome |

| Rights | Whether a stakeholder group has legal, property, consumer, or user rights associated with the decision-making process, the decision outcome, or the environment for which the decision is being made |

| Fairness | Whether the exclusion of a stakeholder group from the decision-making process would lead to the process being viewed as unfair by the community |

| Underrepresented/under-served populations | Whether a stakeholder group includes any underrepresented or underserved populations |

SOURCES: Sharpe et al. (2020, 2021).

In the context of the Federal workforce, this term includes individuals who belong to communities of color, such as Black and African American, Hispanic and Latino, Native American, Alaska Native and Indigenous, Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, and North African persons. It also includes individuals who belong to communities that face discrimination based on sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity (including lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, gender non-conforming, and non-binary (LGBTQ+) persons); persons who face discrimination based on pregnancy or pregnancy-related conditions; parents; and caregivers. It also includes individuals who belong to communities that face discrimination based on their religion or disability; first-generation professionals or first-generation college students; individuals with limited English proficiency; immigrants; individuals who belong to communities that may face employment barriers based on older age or former incarceration; persons who live in rural areas; veterans and military spouses; and persons otherwise adversely affected by persistent poverty, discrimination, or inequality. Individuals may belong to more than one underserved community and face intersecting barriers.

Additionally, other categories are necessary for assessing equity in the distribution of fisheries benefits. These include geographic communities that are dependent or highly engaged in fisheries. NOAA’s social indicator database uses census information coupled with publicly available aggregated permit and landings data to develop indicators of community engagement and reliance (Jepson and Colburn, 2013). This effort uses publicly available information on income and poverty levels at the community level. One potential shortcoming, however, is that the census data are at the community level and may not reflect the economic status of those engaged in or relying on fisheries, directly or indirectly. Data on intergenerational participation or family reliance on fisheries are important categories for individual and community assessments, including the full fisheries workforce and supply chain from captains and crew to processors and distributors.

The committee recognize two groups of potential beneficiaries of particular note: underserved communities as defined by NMFS and citizens of Tribal Nations or Indigenous Peoples.

Underserved Communities

NMFS’s EEJS identifies ‘underserved communities’ as a central subject of equity concerns and defines those communities as sharing either a geographic location or “shared characteristics, history, or identity” (NMFS, 2023b). The EEJS notes (1) underserved communities may include not only fishery participants, but also their dependents, crew, and processing and distribution workers (this is consistent with what is required under National Standard 8); (2) underserved community characteristics vary regionally, and the categories intersect; and (3) the phrase “have been systematically denied” is utilized and consistent with phrasing in other policy instruments that recognize “being underserved” as an historical process, rather than something that can be understood as a present condition (NMFS, 2023b).

Tribal Nations and Indigenous Communities

Citizens of Tribal Nations and Indigenous Peoples in the United States have been historically underserved as both citizens of sovereign nations and racial and ethnic groups and marginalized under past and current fishery management regimes (Carothers, 2011; Langdon, 2008). For example, a recent National Academies report (NASEM, 2021) on limited access privilege programs notes “the tendency for ITQs [individual transferable quotas] to exclude Indigenous peoples or those who are otherwise marginalized politically and economically due to structural factors, such as racism (Young et al., 2018).”

As part of the federal government’s effort to better serve and account for impacts to Tribes and Indigenous Peoples, there has been a growing interest in improving the federal trust responsibility,

Tribal Consultation processes, and recognizing and including Indigenous and Traditional Knowledge in federal decision-making, research, and policies (see Chapter 2). Despite this progress, a key challenge in accounting for the impacts and participation of Indigenous Peoples in federal fisheries (not just treaty fisheries) is lack of data and difficulty in systematic data collection to identify different social and demographic groups that rely on, participate in, and are affected by federal fisheries. Executive Order 13985, on Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government, signed in January 2021, aims to better meet the needs of Indigenous peoples and other people of color who are disproportionately and adversely affected by persistent poverty and inequality (White House, 2021a). Tribal citizens and Indigenous peoples are also uniquely and disproportionally affected by climate change (see Executive Order 14008 [White House, 2021b]; Reidmiller et al., 2017). Progress is also being made to better account for underserved communities, including tribal communities, in federal decision-making. As one example, NOAA’s Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool includes an interactive mapping tool that identifies underserved communities using eight categories of indicators (e.g., climate change, energy, health, housing, workforce development).4

Many examples in the social science literature can help inform NMFS’s approach to better accounting for the ways in which Indigenous and underserved communities may be included in assessments of benefits or impacts of fishery management decisions. For example, Carothers et al. (2010) analyzed data regularly collected by NMFS on halibut individual fishing quota transactions and participants in the North Pacific region to investigate the relationship between halibut quota share transfers and residency in small, rural coastal communities (characterized by populations of less than 1,500). The authors were able to assess the net flow of quota share into and from these communities from available data on quota sales transactions. In addition to residency in small, remote fishing communities, the authors also analyzed age as a variable of interest. The suite of available data drawn on in their analysis, including age and residency of individuals and quota market transactions, revealed that size of community and Alaska Native cultural affiliation are important factors in understanding quota share market behavior. In another example, Carothers (2013) assessed the relative importance of community of residence, cultural affiliation, and demographic variables (i.e., age, gender, ethnicity income and education levels, and fishing participation) in affecting market participation and whether an individual buys or sells quota. These studies are valuable in identifying and understanding potential community-level impacts (be they place-based communities or underserved communities) through analysis of available data collected at the individual level.

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

FINDING 4-1: The beneficiaries of commercial and for-hire fishery management go beyond current permit and quota holders to include others engaged directly in the fishery (e.g., non-permit-holding vessel captains and crew), shoreside facilities involved in processing fishery products, the network that distributes fishery product, local and regional businesses that rely directly and indirectly on fishery activity, and local fishing communities.

FINDING 4-2: While challenging to measure, many of these potential beneficiaries receive both monetary and nonmonetary benefits from participating in fisheries. Nonmonetary benefits include, among other things, meeting social and cultural obligations, prestige, food security and sovereignty, life and occupational satisfaction, and spiritual practices and sites.

___________________

FINDING 4-3: Crew are important potential beneficiaries of fishery management decisions. The committee applauds NMFS’s efforts in surveying this important group. Current challenges in obtaining data on crew include the lack of a sampling frame, which could be provided by a crew registry; infrequent and incomplete surveys of crew at the national level; and the often transitory and vagile nature of employment on fishing vessels. Information on crew at the individual, fishery, regional, and national levels would reflect the distribution of benefits of the issuance of permits and allocation of quota more fully and provide a foundation that would help understand linkages between crew, fisheries, and communities that would aid in the development of criteria for and measures of equity in fisheries.

FINDING 4-4: Shoreside facilities, distribution networks, fishery-dependent industries, and fishing communities are important potential beneficiaries of fishery management decisions. However, data on these important potential beneficiaries are sparse and inconsistently available. Improving the reliability and availability of such data is essential if the full flow of benefits that accrue from permit and quota allocation is to be understood.

FINDING 4-5: NOAA’s Social Indicators for Coastal Communities and Fishing Community Profiles provide useful indices related to the social characteristics of fishing communities. However, these data are often outdated, fragmentary at the national level, and not collected at a frequency to reveal changes in the full flow of fishery benefits to the nation.

RECOMMENDATION 4-1: The National Marine Fisheries Service should commit to regular collection, analyses, and interpretation of social and economic data to characterize the full flow of benefits and beneficiaries from the nation’s fisheries. The committee recommends collecting and, within the extent of the law, disseminating publicly this information at more regular intervals to adequately assess the impacts of management decisions and changes in fisheries.

RECOMMENDATION 4-2: The National Marine Fisheries Service should continue developing community-level indicators of fishing engagement, dependence, and reliance. However, the committee also recommends further developing products that are not geographically constrained or limited by the spatial resolution of census data, which may not always align with the more holistic definition of equity.