Creating an Integrated System of Data and Statistics on Household Income, Consumption, and Wealth: Time to Build (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction and Overview

1

Introduction and Overview

Income, consumption, and wealth (ICW) are the three major components of a household’s economic wellbeing. Their levels, trends, and distributions reflect the overall economic wellbeing of society. Often, researchers use only the levels, trends, and distribution of income to examine people’s economic circumstances, but what people spend (consumption) and their stock of savings (wealth) are equally important, both in assessing economic security and in evaluating economic policy, such as the impact of taxes or transfers on saving and spending. Moreover, analyses of the joint distribution of ICW for the same households—for example, how many households are income-poor but asset-rich and vice versa, or how households finance consumption that exceeds their income—are critical to understanding households’ varying abilities to support material living standards and have control over resources (see Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2013). Such analyses are needed, not only at a point in time but also over time, using longitudinal data to understand how trends in two and three dimensions impact the economic wellbeing and distribution of economic wellbeing of future generations in our society.

The federal statistical agencies provide a plethora of useful data and statistics on ICW. Yet what are policy makers and the public to make of estimates such as the following:

- Median household income, 2022: $74,580 (Guzman & Kollar, 2023) vs. $111,320 (Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2023)

- Mean household expenditures, 2020: $61,330 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023) vs. $103,600 (Garner et al., 2022)

- Share of wealth (assets minus liabilities) held by the top 1% of households, 2022: 34.7% (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2023) vs. 30.4% (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2024)

What are the reasons for these and many other differences in federal statistics for levels and trends in household ICW? They include differences in concepts and definitions, differences in underlying data and estimation methods, and differences in the quality of the underlying data. In many instances, different definitions (e.g., whether to include capital gains or health insurance benefits in income or the services of owning a home in consumption) are appropriate for research purposes, such as estimating the effects of policies on household economic wellbeing over time and across population groups and geographic areas. Yet often differences are not clearly justified or explained, which at best muddies the waters of policy debate and, at worst, enables advocates with different policy perspectives to cherry-pick their preferred set of estimates. Achieving an integrated system of relevant, high-quality, and transparent ICW data and statistics would provide not only a widely agreed-to set of facts about who has how much and from which sources, but also a valuable database for policy analysis and research on the nation’s economic wellbeing. Devoting federal resources to creating such an integrated set of data and statistics would allow tracking of inequality and other distributional concerns not only by ICW groups (e.g., households by decile groups of ICW), but also by age, sex, ethnicity, educational level, geographic location, and types of ICW.

This report is the work of a panel appointed by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Committee on National Statistics (CNSTAT) and sponsored by multiple foundations: the Speigel Family Fund (with help from the California Community Foundation), The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and Omidyar Network. The Panel on an Integrated System of U.S. Household Income, Wealth, and Consumption Data and Statistics to Inform Policy and Research was charged to (a) review the major ICW statistics currently produced by U.S. statistical agencies and (b) provide guidance for modernizing the information to better inform policy and research (such as understanding trends in inequality and mobility). The topics the panel could consider in its review included:

- Appropriate definitions of household, family, and individual ICW; variations in definitions that would be useful for particular

- purposes (e.g., market income before government taxes and transfers); inclusion of particular components (e.g., capital gains and wealth transfers); different reference periods (e.g., subannual vs. annual); and comparability with commonly used international concepts and methods;

- The treatment of and method(s) used to value in-kind benefits and services (e.g., health insurance or transfers of food or housing);

- The treatment of retirement income and plan contributions;

- The population groups (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, and gender groups) for which separate estimates are appropriate;

- The appropriate breakouts of ICW statistics (e.g., by decile groups, top and bottom 1% and 5%);

- The level of geographic granularity for which estimates are appropriate;

- The desired frequency and timeliness of updated estimates;

- Needed quality improvements for relevant data collection programs (including cross-sectional and longitudinal datasets);

- The cost and respondent burden for collecting the data;

- The potential for using multiple data sources, including surveys, state and federal administrative records, and commercial data, as well modeling, to produce integrated, highest-quality estimates; and

- Legal, administrative, and other barriers to creating an integrated system of household, family, and individual ICW statistics.

As part of its deliberations, the panel was charged to evaluate the need for and value of a fully integrated system of ICW statistics to provide consistent macro-level statistics (e.g., total household or family income) and micro-level statistics (e.g., income for households in each quintile group of the distribution). The panel was also charged to produce a final report with conclusions and recommendations regarding the relevance, accuracy, timeliness, geographic and population detail, and consistency of ICW statistics and the need for an integrated system of these statistics.

This introductory and overview chapter provides background for the reader on the need for and the many issues involved in creating an integrated system of ICW data and statistics. It then describes how the panel’s work dovetails with that of U.S. statistical agencies and international groups that focused on developing household distributions of ICW in response to the Great Recession. The chapter ends by reviewing how the panel conducted its work and how the remainder of the report is organized.

HOW (AND WHY) CURRENT MEASURES ARE CONFUSING

Recent headlines demonstrate the confusion created by current income distribution statistics, which is compounded by differences within and among wealth and consumption measures. Researchers also differ on what the data show about changing inequality and economic wellbeing. Strain (2020) and Gramm et al. (2022) argue that the American Dream is not dead, while Desmond (2023) and Mazumder (2018) suggest that it is in serious trouble. Piketty et al. (2018) estimate that income inequality has risen, using top income shares, while Auten and Splinter (forthcoming) show little increase. Meyer and Sullivan (2022) estimate that consumption inequality has fallen over the past 15 years, while Aguiar and Bils (2015) and Fisher et al. (2022) show inequality increasing. Even the available federal statistics show a variety of results: the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) shows income for the median household increasing in real terms, while the Census Bureau shows it as flat over the past 20 years (see also Burkhauser et al., 2023). These differences in findings are not simply a matter of the glass being half-full or half-empty, as the different views of researchers reflect the different data, definitions, assumptions, timing, and estimates that they are using. This confusion has generated the need to create guides to better interpret results, like the CPBB Guide to Statistics on Historical Trends in Income Inequality (see Stone et al., 2020), and before it the work of Johnson and Smeeding (2015). The differences in conclusions are even more apparent for the years surrounding the recent COVID-19 pandemic. For example, changes in median pre-tax income are much smaller than changes in post-tax income due to massive subsidies during the worst of the COVID period (see Creamer & Unrath, 2023).

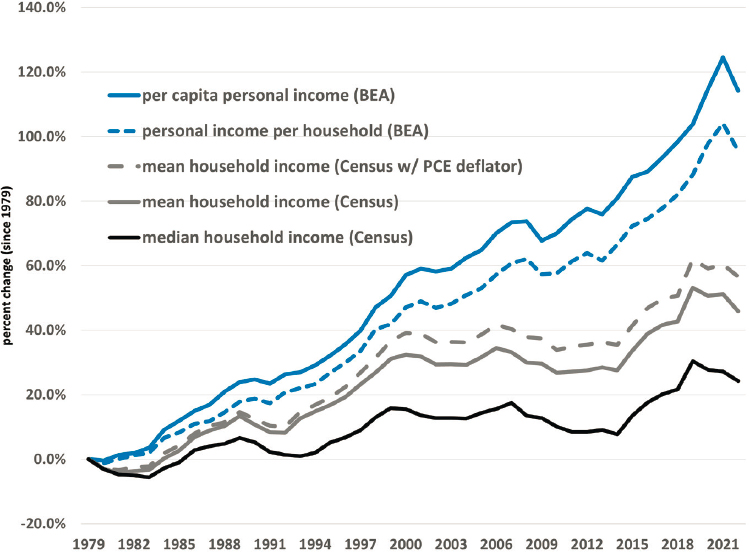

The most widely read national media sources are also confused. For example, the New York Times has displayed a figure comparing gross domestic product (GDP) growth with Census Bureau median income to indicate that GDP is not a good measure of economic wellbeing (see Irwin, 2014; and Figure 1-1). Irwin states, “Growth hasn’t translated into gains in middle class income” (Irwin, 2014, p. 2), illustrating this by showing that the growth in per capita GDP outpaced the change in median household income. However, such comparisons are misleading because they compare an average to a median and they use different definitions of income and different methods to adjust for inflation. As Deaton (2022) mentioned in his remarks to the panel, there is a great need to explain inconsistencies among measures and data sources and suggest ways to close the gaps. As the panel’s title suggests, one of the main needs for an integrated ICW is to improve the information base for research and policy analysis.

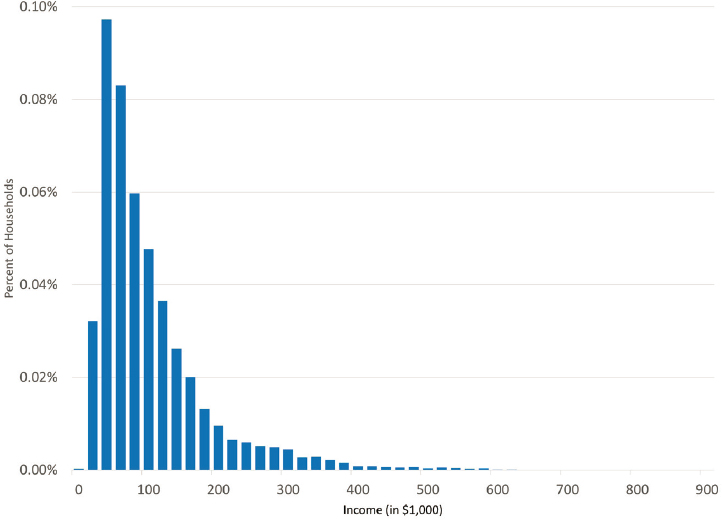

Figure 1-1 confirms the confusion about aggregate growth in per capita personal income, based on Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)

NOTE: BEA = Bureau of Economic Analysis; PCE = personal consumption expenditures.

SOURCES: Panel generated using Fixler et al. (2020), Guzman and Kollar (2023), Bureau of Economic Analysis (2023), and Census Bureau (2017) for smoothing the breaks in the median and mean income series.

data, increasing much more than median household income, based on Census Bureau data. As shown in the figure, real median household income increased only 24.3% (using the Consumer Price Index Research Series [CPI-U-RS] to deflate between 1979 and 2000 and the Chained Consumer Price Index Series [C-CPI-U] from 2000-2022) between 1979 and 2022, while real per capita personal income increased 114.3%, based on the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index.1 This comparison, however, mixes means and medians and different price indexes. Using consistent price indexes and comparing means can account for much of the difference; in fact, the difference in the increase using this method is 58 percentage points compared to 90 percentage points. In addition,

___________________

1 In prior years, Census adjusted incomes using the CPI-U-RS for the entire period, which yields a smaller increase. See tables in Guzman and Kollar (2023) for a comparison of deflators.

using similar units of analysis—mean household personal income (income divided by number of households instead of per capita)—further shrinks the difference to 39 percentage points (96% compared to 57%), a smaller yet still substantial difference. Using similar units and price indexes not only reduces the difference in trends, but also reduces the difference in levels, bringing the differences between Census Bureau money income and BEA personal income closer than those presented above (see also Rothbaum, 2015). The remaining difference is due to measurement errors in the survey data, such as nonresponse, underreporting, and underrepresentation of high-income households, and to different income concepts. BEA’s definition of personal income contains many more sources of income than does the Census Bureau definition of money income in its household surveys. Hence, comparable measures of mean and median household income are needed to assess the actual differences between measures and data sources (see Armour et al., 2014; Fixler & Johnson, 2014; and Fixler et al., 2020).2

The only way to solve these discrepancies is to use similar concepts and measures when comparing trends. With fairly similar income measures and deflators, measures of median household income from CBO and the Census Bureau both show a similar increase between 1979 and 2019 (see Congressional Budget Office, 2023; Guzman & Kollar, 2023). While there are legitimate reasons for the differences among many measures, these differences are not transparent, but rather are confusing to the public, to policy analysts, and to policy makers. Common, transparent, consistent, and accurate measures are needed.

Turning to the trends in inequality and disparity, policies and their evaluation depend on accurate data and consistent estimates. The different levels and trends in Figure 1-1 are due to different measurement choices; it is not that one of them is accurate and the others are not. It is that different measures may be needed for different purposes. How the economic pie is distributed is an increasingly key and divisive issue in public discourse (see Leonhardt, 2023; Szalai, 2023), public opinion, and even elections. Often the discourse simply focuses on one of the estimates in Figure 1-1 (or Figure 1-2), hence, cherry-picking. For example, people want to know what share of households are in the top 1% compared to poverty rates, and who benefits from income support programs vs. who pays net taxes. Public perception is also affected by differences in inflation rates and in income before and after taxes when determining how levels of economic resources have changed (see Galston, 2023). Here again, there is considerable confusion about the levels, trends, and inequities due to alternative data, estimates, and measures.

___________________

2 See also Leonhardt (2023), who finds that using more comparable measures of income, the increase in per capita GDP is similar to the increase in national income (a different concept than personal income, including government expenditures for education and other public goods) for the middle of the distribution.

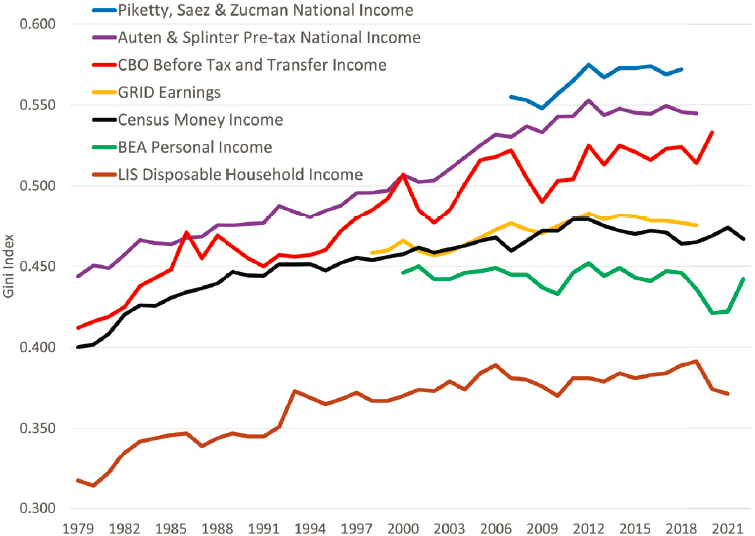

NOTE: BEA = Bureau of Economic Analysis; CBO = Congressional Budget Office; GRID = Global Repository of Income Dynamics; LIS = Luxembourg Income Study.

SOURCES: Panel generated using various sources. Auten and Splinter, forthcoming; Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2023; Congressional Budget Office, 2023; Fixler et al., 2020; Guzman and Kollar, 2023; Global Repository of Income Dynamics, 2023; Luxembourg Income Study, 2023; Piketty et al., 2018.

As shown in Figure 1-2, all income inequality measures3 show an increase in inequality during the past 45 years, but by how much? And who is experiencing these gaps? Again, three of these measures are produced by federal agencies—BEA, Census Bureau, and CBO. And the others use federal data. Attempts to create comparable data series demonstrate that the true differences between tax data and Census Bureau data are not as great as shown here, but still differences remain. And, at present, sorting out the differences requires Herculean research efforts.

Figure 1-2 shows inequality measures (Gini indexes) using seven data series with various starting dates from 1979 through the late 1990s up until 2021 (see Annex 1-1 for a description of alternative measures of

___________________

3 Figure 1-2 uses the Gini indexes, which is determined by examining the shares of income owned by each household, or group of households (such as percentiles or quintiles); see Annex 1-1.

inequality, including the Gini index). All available series indicate an increase in inequality since 1979, with most also showing a leveling off since the Great Recession (2007–2009). However, the levels differ and the actual increases do as well. Notable differences may be seen between the CBO and Census Bureau measures,4 which both use a measure of household income, and the BEA, World Income Database, and Auten and Splinter (forthcoming) measures, which use measures of income comparable to the national accounts. Also included are two measures from international comparison projects: disposable household income from the Luxembourg Income Study and household earnings from the Global Repository of Income Dynamics.5

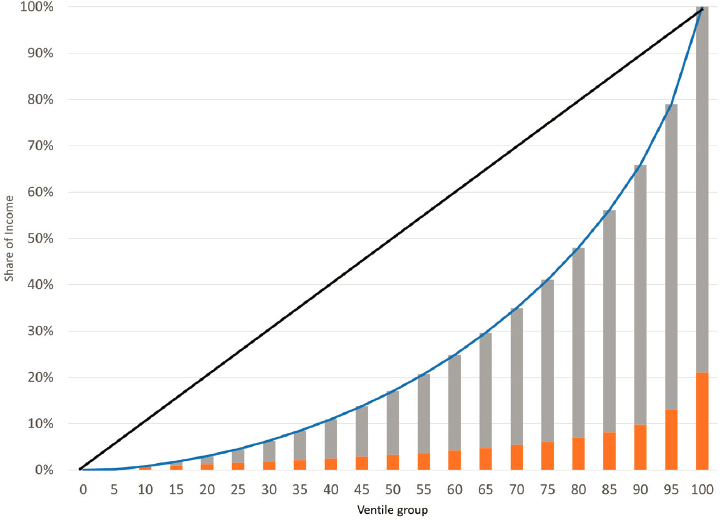

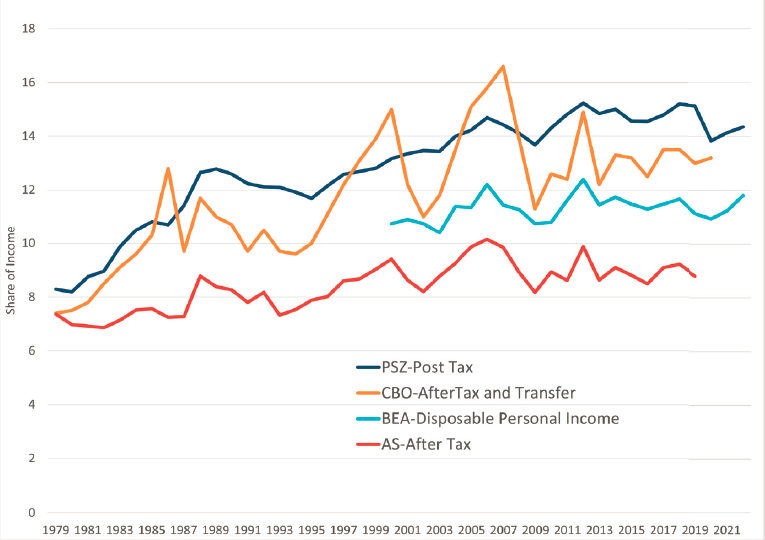

Another commonly used measure of inequality is the share of total income obtained by the top 1% of households (see Annex 1-1). The trend in the share of after-tax and transfer income for the top 1% since 2000 appears very differently depending on how this measure is obtained (see Figure 1-3 and Fixler et al., 2020). Since 2000, the top 1% owned an increasing share of income as measured by BEA and Piketty et al. (2018), but a decreasing share as measured by CBO and Auten and Splinter (forthcoming). Another income measure could include all capital gains (not just the realized gains as in the CBO measure). This measure (as presented in Burkhauser et al., 2023) is similar to the CBO measure showing large volatility and an increase over the period. Some researchers even suggest that there is no need to worry about increased income inequality, because consumption inequality is so much lower—and not rising as much (Meyer & Sullivan, 2023).6 In contrast, Figure 1-4 shows that wealth inequality is much higher than income inequality.

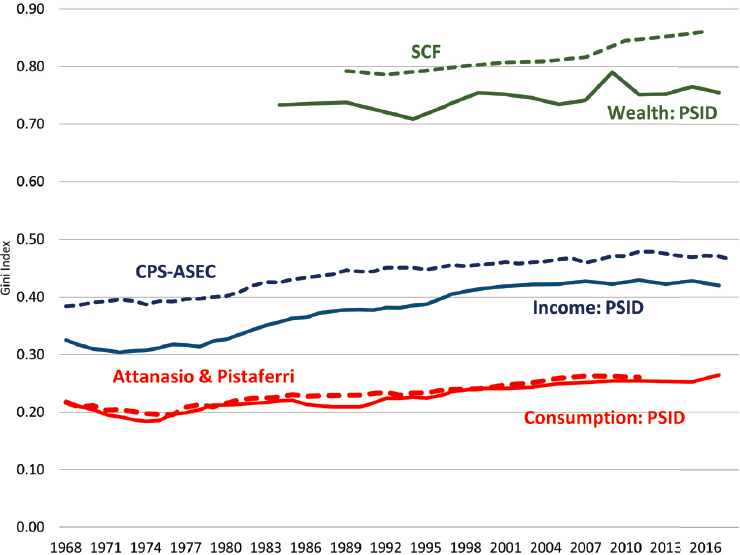

These different trends in inequality are also apparent in comparing the trends in inequality for ICW. Figure 1-4 (from Fisher & Johnson, 2021) shows Gini indexes for ICW from 1968 to 2017. While wealth inequality is greater than income inequality and income inequality is greater than consumption inequality, all show increases over this period. One therefore needs to discuss how the implied trends in economic wellbeing are different using consumption and wealth instead of income.

___________________

4 The Census Bureau’s money-income Gini index is produced by removing the series breaks shown in Census Bureau reports (see Guzman & Kollar, 2023) following suggestions by Armour et al. (2014) and Atkinson et al. (2011).

5 Note that the World Inequality Database measure is similar to Piketty et al. (2018); Fixler et al. (2020) shows a Gini index for the Piketty et al. (2018) measure that is almost identical to the World Inequality Database measure shown here. The Auten and Splinter (forthcoming) measure uses an income concept similar to that in Piketty et al. (2018) and the World Inequality Database, while making other decisions about the distribution; see Piketty et al. (2018) and Auten and Splinter (forthcoming) for a detailed comparison.

6 Meyer and Sullivan (2023) show a fall in consumption inequality since 1984.

NOTE: AS = Austen and Splinter; BEA = Bureau of Economic Analysis; CBO = Congressional Budget Office; PSZ = Piketty, Saez, and Zucman.

SOURCES: Panel generated using various sources. Auten and Splinter (forthcoming), Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2023b; Blanchet et al., 2022; Congressional Budget Office, 2023.

Further, it is important to heed Angus Deaton’s repeated comment that in evaluating inequality, one should be more concerned about horizontal differences than the vertical differences shown in Figure 1-4 (see Deaton, 2022). That is, the greater concern is the increasing disparity between groups, such as Black and White households, rather than the overall increase in inequality for all groups, regardless of using income, consumption, or wealth as the measure of economic wellbeing. For example, the 2022 Survey of Consumer Finances suggested major gains in wealth for most population groups, including Black and White people, compared to 2019, owing mainly to the increased value of owned housing (Aladangady et al., 2023). However, inequality in net wealth rose (Smialek & Casselman, 2023), and the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) data illustrated that differences in Black-White income and asset growth produced different conflicting conclusions.

Although the series differ, multiple measures of inequality may be useful for various purposes. The High-Level Expert Group report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; Stiglitz

NOTE: CPS-ASEC = Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey; PSID = Panel Study of Income Dynamics; SCF = Survey of Consumer Finances.

SOURCES: Panel constructed using data from Fisher and Johnson (2021).

et al., 2018) recommends using multiple metrics, and even a dashboard of various measures.7 In the end, the goal is to be able to determine the overall economic wellbeing of households in the United States. Income is the usual metric; however, wealth shows much more disparity, in the end, and consumption may be an even better measure of longer-term economic wellbeing than either income or wealth.

Moreover, data are needed on the distributions of each component of ICW, paying careful attention to the tails of each distribution and their relationship. While the income share of the top 1% is widely known, far less is known about the top shares of wealth and consumption. The

___________________

7 “No single metric will ever provide a good measure of the health of a country, even when the focus is limited to the functioning of the economic system. Policies need to be guided by a dashboard of indicators informing about people’s material conditions and the quality of their lives, inequalities thereof, and sustainability” (Stiglitz et al., 2018, p. 117).

sources of income within the top 1% are mainly income from wealth or owned businesses (Gale & Vignaux, 2023). In contrast, the lowest 25% of the wealth distribution has massive amounts of non-mortgage debt, more than two-thirds of all debt, with student loan debt being the largest source (Congressional Budget Office, 2023). The bottom 10% of the wealth distribution has negative net worth, meaning that these households are net debtors, that is, their debt exceeds their assets (see Kent & Ricketts, 2024). While consumption inequality is less than income or wealth inequality, there is still a remarkable correlation between its distribution and that of both income and wealth (see Fisher et al., 2022; Krueger et al., 2016).

In addition to looking at the distributions for each of the three measures separately, one can examine them jointly. EUROSTAT/OECD (2022) finds that the distributions of consumption and income are more closely linked than the distributions of consumption and wealth, with the association between wealth and income distributions lying between the previous two. The three distributions overlap more strongly at the tails than around the middle, meaning that households at the top (or bottom) of one distribution tend to belong to the top (or bottom) of the other two distributions as well. Further, the association across distributions is tighter at the top of the joint distribution than at the bottom. Gindelsky and Martin (2023) compare the joint distribution of personal income and PCE to that found in Fisher et al. (2022) and similarly find that a large share of households are at the top of both distributions. Examining the joint distribution of all three measures, Fisher et al. (2022) find that two-thirds of households in the top income and consumption quintiles, respectively, are also in the top wealth quintile—and thus jointly driving inequality.8 Finally, this same study shows that there are increasingly more households in the top 5% of ICW combined over time, suggesting that the rich are becoming more closely intertwined regardless of the measure of economic wellbeing employed.

These findings matter greatly for economic security or vulnerability. Being in debt without secured assets leads to borrowing at high credit card interest rates to support consumption, failing to repay student debt, and doubling up with parents. In contrast, among the wealthiest there is much more room to stabilize the incomes of the youngest offspring (including grandchildren), help them avoid debt, and even add to their secured assets (see Box 1-2 below).

___________________

8 OECD (2023, Figure 1-4) shows that the share of households at different points of the joint distribution of income and wealth, and income and consumption, is highly concentrated for all OECD countries.

THE WHO, WHAT, WHERE, WHEN, WHY, AND HOW OF MEASURING ICW DISTRIBUTIONS

Measuring the distribution of income, consumption, and wealth (whether to measure inequality through one or more indexes or to measure levels and trends) requires first deciding on the measurement yardstick. That is, whose standard of living is one measuring, how will it be measured, and how will it be updated over time? One must also determine what resources to measure, whose resources to measure, over what period and geographic area, and, for purposes of studying inequality and mobility, how to measure the disparities and for what specific purpose. Basically, it is necessary to first identify the who, what, where, when, and why, and then taking all those decisions together, one can arrive at the how.9

What: The Choice of Income, Consumption, and Wealth Concepts

Ever since one of the first National Bureau of Economic Research meetings of the Conference on Research in Income and Wealth (1943), researchers have discussed the many choices that need to be made in determining the appropriate components of income to include in a measure of income distribution (see Box 1-1 for a brief history of the measurement of ICW). A multitude of income measures are used by researchers and the government in examining inequality and other aspects of the distribution of economic wellbeing (see Congressional Budget Office, 2023; Guzman & Kollar, 2023).10

The most inclusive concept of income and consumption derives from the suggestions of Robert Murray Haig and Henry Calvert Simons. Haig (1921, p. 27) stated that income was “the money value of the net accretion to one’s economic power between two points of time,” and Simons (1938, p. 50) defined personal income as “the algebraic sum of (1) the market value of rights exercised in consumption and (2) the change in the value of the store of property rights between the beginning and end of the period in question.”

In a paper prepared for the panel, Levy (2023, p. 2) highlights reasons for measuring income: as an indicator of economic wellbeing and a measure of poverty, and “[…] for the purpose of taxing it.” Levy (2023, p. 3) continues in the examination of Haig-Simons for the inclusion of in-kind benefits, suggesting:

___________________

9 This sections follows the approach in Johnson and Smeeding (2015) and Fixler et al. (2020).

10 See also Brooks (2018), who defines 13 measures of income.

[between] the original authors of the Haig-Simons framework, Haig (1921) did not address the treatment of in-kind transfers, but Simons (1938) recognized them as a thorny problem in his treatise on income taxation.11

Recent work demonstrates how to construct a Haig-Simons income measure using current data (see Larrimore et al., 2021). Economists have used the Haig-Simons income definition to produce the equation (or budget identity) showing that income (I) equals consumption plus the change in net worth (W). In an attempt to relate all three components, the Canberra Group Handbook on Household Income Statistics (2011, p. 10) states: “Household income receipts are available for current consumption and do not reduce the net worth of the household through a reduction of its cash, the disposal of its other financial or non-financial assets, or an increase in its liabilities.”

BOX 1-1

Early Efforts to Measure Income, Consumption, and Wealth

Research on improving the measurement and distribution of ICW and their importance for measuring economic wellbeing has been undertaken for more than a century. The first National Bureau of Economic Research report, released in 1921, was entitled, “Income in the United States: Its Amount and Distribution, 1909–1919” (Mitchell et al., 1921). The report focused on measuring the distribution of income in a manner consistent with the national accounts, specifically how the “National Income is distributed among individuals.” Building on this report, Simon Kuznets led the way to build the national accounting system in the United States, with the comment in his report to Congress in 1929 that “the welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income,” arguing that its distribution is also important (Kuznets, 1934, p. 6).

The measurement of consumption has been continually improved at the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), and studies of family living conditions rank among the oldest data collected. The first nationwide expenditure survey was conducted during 1888–1891 to study workers’ spending patterns as elements of production costs (see Johnson et al., 2001).

The history of wealth measurement begins with an early evaluation of the distribution of income and wealth published by John Bates Clark in 1899 (Clark, 1899). King (1927) produced the first distribution of wealth in the United States for the early 1900s, using a capitalization method (see also Lampman, 1962). The first measures of household wealth occurred with the first wealth survey (precursor to the SCF) in 1948 (Income and Wealth Inequality in America, 1949–2016).

___________________

11 English versions are found in the references in Simons (1938) and Brooks (2018).

While most examinations of inequality and economic wellbeing use income, other research suggests that consumption may be a more appropriate indicator of permanent income and, hence, a better measure of inequality and economic wellbeing (see Cutler & Katz, 1991; Meyer & Sullivan, 2023; Slesnick, 1994). Johnson and Shipp (1997) show different trends in income and consumption inequality and demonstrate that consumption inequality was lower than income inequality and that the increases in both income inequality and consumption inequality were similar during the 1980s (see also Attanasio & Pistaferri, 2016).

Yet as a marker of social and economic status, wealth could arguably be a better measure of a household’s economic position in society. Wealth or net worth measures represent the accumulation of saving and economic success. It tells you what families can actually do to invest in their future, or to act as a family safety net. Wealth alone says the most about the long-term economic prospects of that family and its children and grandchildren. If so, wealth or net worth itself may be used as the ultimate measure of inequality and economic wellbeing. Here the evidence is sketchier and the answer is more dependent on valuing both private and public pensions as well as businesses and financial holdings. For recent studies of wealth inequality, see Aladangady et al. (2023), Saez and Zucman (2016), and Wolff (2021). Recently, Fisher et al. (2022) and Heathcote et al. (2023) show the trends in inequality for all three dimensions.

Who: Whose Resource?

To examine the distribution of resources (ICW), researchers need to determine whose resource to evaluate, that is, the unit of analysis. The focus in the national accounts has always been per capita personal income (or per capita GDP). Piketty et al. (2018), along with others who work with tax data, use a tax filing unit as the unit of analysis. This could be a married couple with two dependents, for example, or a single adult, which could be smaller than the household. Most distributional research uses the household as the unit of analysis (see Congressional Budget Office, 2023; Guzman & Kollar, 2023), and the Canberra Group (2011) treats the household as the international standard. The significant differences between these metrics can result in different effects on the distribution of income, consumption, or wealth.

Because households with more members may need additional income to be equally well off compared to smaller households, most studies also adjust household income by an “equivalence scale” to adjust for economies of scale within the household—for instance, equivalizing income using the

square root of household size or some other adjustor (see Buhmann et al., 1988).12

The family is also an important unit of analysis. Individuals share resources with family members. People who live together also share resources. Yet members of the same family may live in different households, and some people who live together are not members of the same family (see Fomby & Johnson, 2022, for a discussion of changing and complex families). While households are the preferred unit of analysis in this report, improved measures of the family—both within and across households—and measures of who lives together and shares resources are important for many data users and data uses, and they merit continued attention by statistical and other data collection agencies.

When: Adjusting Resource Over Time

To create measures of trends in income (or consumption or wealth) and the distribution of income, one must choose a reference period and methods to adjust for changes in the cost of living that occur during the time period. Most studies use annual measures of income. Monthly or quarterly measures of income are typically more volatile, without necessarily providing meaningful information on inequality or other distributional trends. Alternatively, if the goal is to measure permanent income or consumption, which requires more stability, averaging over longer periods (years) may be more appropriate (see Cooper et al., 2023).

As discussed in Fixler et al. (2020), when measuring the level of real income, a price index is necessary, such as the PCE deflator or the CPI to adjust for changes in prices over time. While different price indexes lead to a variety of changes in the level of the median and mean and to changes in the levels of various quintiles, they do not affect the trend in inequality measures (as shown in Figure 1-1). The Census Bureau currently uses both the CPI-U-RS and the C-CPI-U to deflate the trends in real mean and median income, while BEA uses the PCE price index, which rises more slowly.13 As shown in Figure

___________________

12 Constant scale elasticities, as described in Buhmann et al. (1988), adjust income by dividing by a scale defined as household size raised to the power, e. When e = 1, it is per capita, when e = 0, it means no adjustments, and e = 0.5 yields the square root scale used in international comparisons and recommended in Buhmann et al. (1988). For a systematic analysis of how poverty and inequality estimates vary with changes in e, see Coulter et al. (1992) and Jenkins and Cowell (1994).

13 The price indexes produced currently at BLS are the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U), Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers, and Chained CPI-U (C-CPI-U; www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm). CPI Research Series Using Current Methods (R-CPI-U-RS) and the C-CPI-U are the current price adjustment methods used by the Census Bureau in creating real income.

1-1, using the PCE price index, mean income increases more over a longer period.14 Fixler and Johnson (2014) and Nolan et al. (2018) show the impacts of price indexes on the changes in median income; however, inflation can affect inequality measures if price changes are different for those with high vs. low incomes or for different geographic areas.15

Where: How Are Measures Adjusted for Differences in Geographic Location?

Similar to adjusting for differences in family size, geographic location could present different living costs that require adjustment, especially in a large country or even in different countries. BEA has constructed a regional price parity index to adjust state-level personal income for differences in prices and living costs. But differences within regions may dominate differences across regions, thus hiding the true extent of household inequality. BEA shows that using regional price parity to adjust for state-level differences in inequality narrows the income differences across states, so inequality is lower across the country than when using unadjusted income (see van Duym & Awuku-Budu, 2022).16

In making comparisons across countries, the Canberra Group report (2011) suggests using national price indexes and adjusting for purchasing power parity differences between countries. OECD (2024) also provides guidance suggesting that inequality should be examined using income-specific indexes as well as geographic-specific indexes (see Fixler et al., 2020).

How: Which Dataset and Summary Statistic?

As discussed in Fixler et al. (2020), different datasets yield different levels of measurement error. In the case of income, research using the Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS-ASEC) has found a significant amount of underreporting of property income, pension income, and public transfers (Meyer et al., 2015; Rothbaum, 2015). Rothbaum (2015) shows that while aggregate wages as measured by the CPS-ASEC are fairly close to the national account totals, interest and dividends are substantially lower. Meyer et al. (2015) show that government transfers in the CPS-ASEC are underreported.17

___________________

14 Between 1979 and 2018 real mean household money income increased 35% (Semega et al., 2019); using the PCE price index to adjust for inflation would yield a 51% increase.

15 See Sherman and Van de Water (2019) and ITWG (2021) for a discussion about whether inflation is higher for those experiencing poverty.

16 Fixler et al. (2017) show how price differences could affect the level and trends in inequality across states.

Similar to Figures 1-2 and 1-4, research usually focuses on the levels and trends in the Gini index to evaluate inequality (Annex 1-1). There are, however, a variety of inequality measures, as in the annual Census Bureau income reports, Guzman and Kollar (2023; see also Atkinson, 1970; Sen, 1997; Theil, 1967). As mentioned earlier, the Gini index is determined by examining the shares of income owned by each household or group of households (e.g., percentile or quintile groups). Hence, the top 1% owning 20% compared to 15% of all income would lead to higher Gini indexes. As discussed in Annex 1-1, the Gini index satisfies a variety of properties that are valuable in evaluating inequality, such as being unaffected by a proportional increase in everyone’s income, but falling if income shifts from a higher income person to a lower income person.18 Another metric is the concentration of income measured by shares of total income owned by the top percentile groups of the distribution (as shown in Figure 1-3 and discussed in Annex 1-1). The latter measures are more volatile and can increase more than overall inequality measures that capture the entire distribution (Alvaredo, 2011).

Why: The Purpose of the Measure

Each of the choices—what, who, where, when, why, and how—has different implications for the levels and trends of ICW, and for measures of inequality. As a result, researchers need to decide on the purpose of their evaluation when making these choices, whether it is to answer questions about overall changes in inequality, the redistributive impacts of government taxes and transfers, or the differences between annual and permanent income. Answering each of these questions may require different data and inequality measures. For instance, calculations of annual vs. permanent income require a panel dataset or longitudinal administrative data that follows individuals, not just households, over a long time period.

In its production of data on the distribution of personal income, BEA’s purpose is to create a decomposition of income that can be related to growth, while CBO’s purpose in estimating household income is to assess the distribution of the tax base, and the Census Bureau’s purpose is to measure the distribution of money income (as used in the official poverty measure). As stated by David Ellwood and Lawrence Summers in their article for the 1985 Conference on the Measurement of Non-Cash Benefits: “It is clear that income distribution statistics have many uses in both formulating and evaluating policy, and in research. The appropriate income concept depends on the question being considered” (Census Bureau, 1986, p. 24). In addition, Gale (2023, p. 2), in his presentation to the panel, stressed that “[…]

___________________

18 See Sen (1997) for a discussion of these properties.

it may be more helpful to provide more information to researchers so they can develop their own measures than it would be to invest in trying to create the perfect measure.”

IMPORTANT RESEARCH QUESTIONS USING ICW

Given the importance of “why,” the panel considered various research and policy questions that require consistent estimates of the distributions of ICW. These research and policy questions include using inequality as a measure of changing disparities by both income groups (vertical) and demographic groups (horizontal), the impacts of life-cycle changes in ICW, evaluating how spending changes with new government cash transfers and tax policy changes, what impact changes in ICW have on family hardship, retirement, and debt, and what the differences are in intergenerational mobility. And of course, questions also include the period over which one wants to measure those changes: recessions and recoveries of all kinds, and business cycles. The list of topics discussed here is suggestive and not definitive, because space precludes a longer list of questions. The panel’s goal is to suggest a transparent and feasible set of measures to provide the evidence to address inevitable new and not yet foreseeable policy issues as they arise.

Measuring Disparities in Economic Wellbeing

One of the most important and most basic public policy questions is whether economic wellbeing is increasing and whether these improvements are equally shared across the population. Basic research on the economic wellbeing of the country requires the distributions of ICW, their joint distributions, and regular, consistent estimates of the distributions and disparities for ICW. These can be used to assess policy, such as the antipoverty impact of government transfers and how public and private transfers affect the income distribution (as with tax evaluation), and to determine which components of consumption and wealth affect trends in inequality. In the United Kingdom, for example, the Institute for Fiscal Studies conducted an extensive review of the importance of inequality and its impact on policy in what is known as the Deaton Review of Inequalities (see Bourquin et al., 2022, for measures of ICW inequalities).

As shown earlier in this chapter, simply understanding the levels and trends in resources and inequality requires consistent measures of ICW. Some suggest that little is known about consumption inequality relative to income inequality, simply because measurement issues are a big obstacle between the two (see Attanasio & Pistaferri, 2016; Krueger & Perri, 2006; Meyer & Sullivan, 2023). The persistent increase in wealth inequality and

the returns to wealth raise additional questions (e.g., see Aladangady et al., 2023; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2023; Jacobs et al., 2021; Sabelhaus & Thompson, 2022). The critical factor in comparing trends in inequality across all three dimensions in a balanced way is to use the Haig-Simons budget identity to ensure that the definitions are consistent (see Chapter 2 and Heathcote et al., 2023).

In his presentation to the panel, Deaton (2022) argued that saving, spending, and the accumulation of wealth cannot be reliably studied without consistent data across all three dimensions. He emphasized the importance of producing statistics that relate to people’s perceived reality, noting that the inclusion of banking services and the full value of health care cost in personal income is not always helpful in this regard; focusing on horizontal inequalities among population groups, defined by, say, education and race/ethnicity; accounting for billionaires; and giving full attention to the role of wealth inequalities. Boushey (2021) in her presentation to the planning committee for the panel study similarly stressed the importance for policy making of measures that take the economic wellbeing of the middle class of American workers into account. She emphasized the usefulness of more frequent statistics (i.e., more frequent than annual) and the need for distributional measures for published aggregates, such as personal income and personal consumption expenditures, which BLS and BEA have recently started to produce.

Blundell (2014, p. 316), in his address to the Royal Statistical Society, highlighted the importance of all three measures, stating that “[…] the results of the research presented here provide a strong motivation for collecting consumption data, along with asset and earnings data.” In fact, there is a need for consistent ICW statistics to be part of the standard toolkit of economic statistics produced by government agencies, in the United States and internationally.

Improving Other Policy-Relevant Measures and Analyses

Improving estimates of ICW will also impact other measures important for policy. In particular, evaluating macroeconomic policy over the business cycle requires household measures of ICW. Improved measures of household income will directly affect measures of poverty and analyses of the impacts of tax and transfer policy on labor supply, spending, and savings. Levy (2023) and Simon and Carpenter (2023), for example, highlight the impacts on income of accurately measuring in-kind health insurance benefits. Han et al. (2020) and Parolin et al. (2022) show how different data yield different results in examining monthly poverty rates. Improved estimates of consumption and spending can affect the CPI through the

market basket weights. And improved wealth estimates provide details on tax policy and its role in subsidizing or shrinking the growth of wealth. In turn, the shifts in demographics and household structure, coupled with the changing economic environment, have direct impacts on the dynamics of the economy. With better ICW data, researchers and policy makers can identify households’ financial needs possibly before they turn into big problems, and then design improved targeted government transfer programs to alleviate households’ financial stress. Some research projects require joint distributions—for example, research on retirement decisions requires data on income and wealth, and then on consumption change or stasis after retirement. Research on poverty requires data on income and consumption, and research on housing and debt financing requires data on consumption and wealth.

Better data on ICW, and the joint distribution of the individual measures for households, can help with developing estimates of the impacts of short-term cash transfers, such as the 2020-2021 Economic Impact Payments (EIPs), the 2021 monthly Child Tax Credit (see Fisher et al., 2024), and enhanced unemployment insurance. In estimating the impact of the EIPs (see Chetty et al., 2017; Ganong et al., 2020; Parker et al., 2022), the overall picture remains incomplete. As stated by Gelman and Stephens (2022, p. 119), “Our understanding of who received EIPs along with other benefits is poor because of a lack of public data.” Wheat (2022) highlights how the JP Morgan Chase Institute can use its bank account data to examine the interaction of assets, income, and consumption to evaluate policies such as the EIP, Earned Income Tax Credit, unemployment insurance, and the Child Tax Credit (see also Ganong et al., 2020). With all available data on receipt, spending, income, and bank accounts, it may be possible to assess how well EIPs and other temporary programs worked to provide relief during the pandemic, and even beyond. But without consistent data on the relationships between ICW, estimates of households’ marginal propensities to consume from these new transfers will continue to vary, which will in turn affect estimates of the impact of assets and debts on marginal propensities to consume (see Carroll et al., 2017; Ganong et al., 2022). In addition, complete data on other government programs would be needed to ascertain how these new transfers interacted with existing programs.

With joint distributions of ICW, macroeconomic models can better reflect the underlying dynamics and heterogeneity across households (see Fisher et al., 2022; Krueger et al., 2016). For example, families without a member holding a college degree experienced only a 4% increase in median income between 1970 and 2019, while families with at least one member holding a college degree experienced a 24% increase. But since 2018, the biggest gains in wages have accrued to the lowest paid and lowest skilled

workers (Aeppli & Wilmers, 2022) while unionization is also bolstering blue collar wages (Leonhardt, 2023).

Wealth gaps by education are also large, and growing; currently, three-quarters of net wealth is owned by college graduates (Case & Deaton, 2023, p. 38; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2023). The joint distributions of wealth and consumption are needed for Kaplan et al. (2014) to identify that households are more than just low wealth or high wealth, and for Krueger et al. (2016) to examine the changes in the distributions of income and consumption for the wealthy. Furthermore, improved, consistent ICW data can help calibrate macroeconomic models such as the ones found in Benhabib et al. (2011); Heathcote et al. (2010); Hintermeier and Koeniger (2011); Kaplan et al. (2014); Krueger et al. (2016); and Krusell and Smith (1998). For example, Mian et al. (2020a,b) use joint distributions (see Fisher et al., 2022) to examine the savings glut of high-income households, using a model whereby the higher share of consumption from high-income households leads to the increasing debt of lower-income households.

CBO, the Joint Committee on Taxation, and the Tax Policy Center (Rosenberg, 2013) use specific measures of income to evaluate tax policy, tax incidence, and the distributional impacts of taxes (see Congressional Budget Office, 2023; Gale & Vignaux, 2023). Questions such as what data are needed to enforce taxpayer compliance (see recent work by Hendren, et al., 2023), what data would be needed to implement a wealth tax, and what effects different kinds of taxes and transfers have on the distribution of ICW are all unanswered at present. Habib and Heller (2022) use the CBO income distribution measure to evaluate the impacts on inequality of various policy changes. Larrimore et al. (2021) demonstrate similar impacts using Internal Revenue Service tax data. But the two studies use different income measures for their purposes and end up with different results.

Policy makers are constantly trying to assess the extent of hardships and their severity among households and the effects of income support policies on these and other outcomes. With the pandemic, several papers used new data to try to capture the changes in hardship that U.S. families were facing (Blount & Minoff, 2022; Parolin, 2023). There also has been great interest in assessing changes in wellbeing over the Great Recession and how that recession differed from the pandemic recession. Many factors impact the ICW of families over business cycles, from the changing value of their homes, the interest on their debts and mortgages, their earnings, how they are consuming, and transfer policy impacts on emergency savings or consumption. Good ICW data are a bedrock need for these kinds of assessments.

Evaluating which safety net or public programs enable households to meet their needs or smooth consumption requires data on multiple

resources: income, consumption, assets, and debts. Understanding what resources people use to purchase food and necessities—earnings, government transfers, interhousehold transfers, dis-saving, or debt—is important for setting policy (see Gonzales et al., 2024; Hamilton et al., 2022; Hardy et al., 2023). Such questions as these, about how policy or life events impact individuals and households, are best answered by following units and individuals over their life course as assets and consumption change by accumulation or decumulation (see Fisher & Johnson, 2023; Shiro et al 2022).

Retirement Security and Wealth Transfers

Retirement security and how it varies by group is another key concern in assessing distributions of ICW. Questions abound about continuing consumption patterns once earnings cease (the retirement consumption paradox) and about planning for retirement. Debt and financial vulnerability, planned savings and bequests, as well as managing debt in old age, are all key policy questions. In his presentation to the panel, Poterba (2023) suggested that pension income is critical for constructing distributional balance sheets for older households, and that omitting Social Security creates a skewed picture of retirement security (see Rohwedder et al., 2022). Wealth helps support consumption over the lifetime, and wealth enables households to support their consumption even with unexpected changes in income. For a long time, it has been argued that such life-cycle impacts are critical in understanding changes in consumption due to changes in income and wealth (Ando & Modigliani, 1963; Friedman, 1957).

Wealth is also important in evaluating the effectiveness of Social Security in old age. Do households plan retirement taking future Social Security benefits into account, and hence, impacting current consumption, savings, and retirement decisions? Do people fall out of the top income decile group because they lack wealth when they retire? Complete and consistent data on income, assets, and debts are needed to examine these questions. Wealth is also a story of intragenerational accumulation and its ultimate intergenerational distribution among offspring, children and grandchildren alike. Debts, unlike assets, cannot be passed on to one’s children in the United States. But longer-term unsecured debts also preclude the ability to make transfers to children or other family members at times of need across the children’s life cycle and into young adulthood.

One key policy concern regarding wealth is that the bottom 25% of households have negative wealth (and hence debt), which leads to important self-sufficiency questions. Does high debt indicate issues independent of low income? How often are households categorized into higher income or consumption deciles with a lot of debt—and then, what types of debt?

Secured debt can help one increase consumption beyond income and this will show higher wellbeing if consumption and housing wealth are examined alone. Debt also contributes to horizontal inequities, because less advantaged and minority households tend to hold less debt, on average, than more advantaged households, but face higher debt/income ratios because much of that debt is not secured by an asset (Avtar et al., 2021; Dwyer, 2018; Houle, 2014; Kramer-Mills, 2024; Sullivan, 2012). And more information on debt is needed to evaluate subprime loans, such as payday loans, title loans, non-prime borrowing, and legal debt. In evaluating the responses to the EIP, Koşar et al. (2023) find that much of the money went to paying off debt. With credit card debt at an all-time high today, data are critically needed to examine whether debt improves wellbeing (as in the case of home ownership debt), contributes to keeping families in poverty, or contributes to bankruptcy (see also Ganong & Noel, 2020).

Following people over time and across generations provides key information about inequality dynamics and opportunity. Friedman (1962) suggests that even with high annual inequality, economic mobility could be “a sign of dynamic change, social mobility, equality of opportunity.” Renewed attention to social mobility is also compelled by an increase in immobility (persistence of economic position across generations) and inequality (see Box 1-2 for more details on mobility and interhousehold transfer). Krueger’s use of the “Great Gatsby Curve” to describe the negative cross-national correlations between income inequality and social mobility across nations (Krueger, 2012) demonstrates the importance of studying these intertwined phenomena. In his remarks to the panel, Chetty (2022) stressed the need for consistent data and measures of income mobility (see also Fisher & Johnson, 2023; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2023d; and Box 1-2 on the importance of longitudinal ICW data over time and across generations).

Stimulated by Krueger’s focus on the Great Gatsby Curve, there has been much research on various aspects of intergenerational mobility (see Corak, 2013, for income; Pfeffer & Killewald, 2018, for wealth; and Arellanoa et al., 2023, for consumption; as well as Deutscher & Mazumder, 2023; National Academies, 2023c). Mulligan (1997) uses the Panel Study of Income Dynamics to detail intergenerational mobility in ICW. Fisher and Johnson (2023) improve upon Mulligan (1997) by measuring children’s income and wealth as they age. Many have examined the differences in ICW mobility for various demographic groups as well (see Black et al., 2020; Bloome, 2014; Fisher & Johnson, 2023; Chetty et al., 2018; Jácome et al., 2021; Mazumder, 2018; Ward, 2021).

BOX 1-2

Intragenerational and Intergenerational Mobility: The Importance of Wealth Accumulation and the Capacity to Transfer Wealth Across and Within Generations

The impacts of policy changes that have been analyzed mainly through the lens of income merit an assessment of the ways they have influenced wealth, debt, asset accumulation, spending from assets, and asset transfer. For example, accumulated family wealth creates the ability to finance college, as well as new homes and businesses for the offspring of high-wealth families. The role of interhousehold transfers and their effects on social and economic mobility over young adults’ life cycle are important questions that require ICW data (see National Academies, 2023d, Ch. 11, for suggestions on improving data on measuring intergenerational effects).

The accumulation of assets over time by one generation is the precedent for transferring wealth across generations, while failure to accumulate such assets handicaps the ability of low- wealth families to aid their offspring. Today organizations from the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank to the Aspen Institute and the Pension Research Council are promoting ideas and ways for households to accumulate liquid and illiquid assets (e.g., see Aspen Institute, 2021). Recent work by Shiro et al. (2022) makes an important start on describing the accumulation of assets over time, but it could be expanded to look at the timing and patterns of emerging from a net unsecured-debt position to a net positive wealth (net worth) position as generations mature. For example, Bauluz and Meyer (2023) note a generational steepening of the age-wealth profile and increasing dis-saving among richer older generations, both facts consistent with the ability to make increased intergenerational transfers of assets across two or even three generations.

Recent research has shown that high family wealth begets higher child and grandchild wealth, but the exact mechanisms are not well identified. Timely additions to wealth, or the avoidance of debt, occur most likely through transfers at critical life stages to finance education, asset purchases such as homes and cars, and business start-ups across two or more generations (Pfeffer & Killewald, 2018; Toney, 2022). Inheritances or bequests at the death of the last member of a parental generation are

Finally, the lens of geography and segregation is critical in examining disparities in economic wellbeing and impact of government policy, such as housing market dynamics and access to financial services and the long-term consequences of redlining and other federal housing policy. While income flows and wealth holdings are an important gauge for assessing power relations within a community, a narrower economic view is that what really matters for people’s economic wellbeing is what they are potentially able to consume over time—including assistance across generations as consumption for the donor generation.

Neighborhood quality is also important for children’s economic mobility. Children whose parents locate in affluent areas enjoy better schools,

also important, but happen at much later ages (see Wolff, 2023). And grandparental transfers can accrue as windfalls to those of younger ages.

Private interhousehold transfers from person to person or as purchases on behalf of a person (e.g., payment of college tuition for a younger family member, or cosigning a mortgage for their home purchase), or as gifts to a person (e.g., an auto, or an inheritance from an older family member) can have longer-term effects on recipient generations’ social and economic growth (Blanden et al., 2023; Gilarine et al., 2023). Income and wealth levels, business and real estate holdings, and transfers across generations are important drivers of economic persistence and intergenerational immobility.

These outcomes can be contrasted with those for people whose families had low intragenerational wealth accumulations or extended debt and who were unable to help their offspring afford higher education financial assistance, obtain a first home, hold an unpaid internship leading to a long-term secure job, or finance a business start-up, among other mechanisms for strategic economic transfer assistance across generations (Haney, 2018; Toney, 2022; Zhong & Andre, 2021). These transfers also act as insurance for the next generation, which can impact both income and consumption. A recent paper examining the heterogeneity of consumption due to income shocks finds differential persistence of intergenerational consumption among children of higher-status households and suggests that “the heterogeneous responses that we find might in part reflect heterogeneity in access to other sources of insurance such as parental insurance” (Arellanoa et al., 2023, p. 4).

These monetary transfers can also occur within a generation, for instance through child support or alimony paid or received. They also include remittances, transfers made from U.S. immigrants or other relatives to families in their home country, which are quite large in some instances (Porter, 2023). Including interhousehold transfers in the measure of income and wealth has important impacts on measuring current economic wellbeing and how this economic status is transferred to future generations.

Assessing the effects of intragenerational mobility or wealth accumulation across the life course and addressing how intergenerational mobility is affected by transfers of money across generations requires longitudinal panel datasets that follow individuals, families, and offspring and their ICW across time.

safer neighborhoods, more affluent families, and better educated peers. Spillovers from higher housing prices have been shown to affect tax yields and the quality of education in such districts (Gilarine et al., 2023). With consistent ICW data, researchers could examine these and other characteristics of neighborhoods that impact mobility, and the differential patterns in income, wealth, poverty, and consumption across neighborhoods; the impact of education, house values, and patterns of wealth in a neighborhood; and how neighborhood attributes of wealth or poverty impact the mobility of children and the longer-term wellbeing of individuals. Recent work by Chetty and colleagues (Chetty et al., 2014) has identified the importance to lower-income children of growing up in neighborhoods with higher

educated peers, less crime, and adult role models. This follows the work of Gennetian et al. (2013) and Ludwig et al. (2013) on schooling, crime, and job outcomes for younger children who move from bad to better neighborhoods using housing vouchers or other housing supports.

U.S. AND INTERNATIONAL INITIATIVES TO IMPROVE INCOME, CONSUMPTION, AND WEALTH DATA AND STATISTICS

It seems clear that no single dataset or measure of ICW can answer all relevant questions, whether by the media and the public, policy makers, or researchers. For consistent, informative statistics on ICW, statistics-producing agencies will need to integrate multiple data sources (e.g., surveys and administrative records) to improve data quality and agree on preferred concepts, units of analysis, and other aspects of ICW measures. For research on disparities across groups and over time, integrated ICW datasets will be needed that enable analysts to apply their own definitions and other aspects as appropriate for their analyses. For the purposes of measuring wealth transfers across time or income or wealth changes over time, longitudinal panel surveys (such as the Panel Study of Income Dynamics and the Health and Retirement Survey) will be needed. Finally, while panel data approaches will help discover the dynamics of income and wealth use over a longer period, cross-sectional joint distributions are the more immediate goal.

The call for improved measurement of ICW was supported decades ago by Friedman (1957, p. 6) who stated: “Its essential idea is to combine the relation between consumption, wealth, and income suggested by purely theoretical considerations with a way of interpreting observed income data […]” Hall (1979) similarly examined the life-cycle-permanent income hypothesis and the relationships among household ICW. But it took the Great Recession to motivate statistical offices to develop improved distributional measures of ICW.

The Stiglitz Commission (Stiglitz et al., 2009, p. 33) called for improved measures of the distribution of ICW based on the national accounts, which OECD endorsed in its formation of expert groups by stating “[…] the most pertinent measures of the distribution of material living standards are probably based on jointly considering the income, consumption, and wealth position of households or individuals.” The OECD High Level Expert Group echoed that recommendation by encouraging international national statistical offices to develop “[…] measures of the joint distribution of household income, consumption and wealth” (Stiglitz et al., 2018, p. 117). These OECD groups motivated many national statistical offices to create household distributions of their national income accounts, following the System of National Accounts (SNA). OECD and Eurostat launched a first joint Expert Group on Disparities in a National Accounts Framework to

carry out a feasibility study on the compilation of distributional measures of income, consumption, and savings across household groups consistent with national accounts definitions and totals (Eurostat, 2020; Fesseau & Mattonetti, 2013) and produced an initial report, with the final report just released (OECD, 2024). While some international statistical offices have produced official estimates of the distribution of ICW, this enterprise is still in its infancy (see Annex 1-2 for details on the National Income and Product Accounts).

Another international effort to create consistent distributions of income and wealth is the World Inequality Database19 (see Chancel et al., 2022), which started in 2011 and has expanded to produce distributions of income, wealth, and labor income by gender for almost all countries in the world. A third international effort is the Luxembourg Income Study,20 which began in 1983 to provide harmonized estimates of the distribution of household income and expanded to a wealth component in 2005 (Luxembourg Wealth Study) and soon plans to add consumption to the mix (see Gornik, 2021). Finally, a recent international effort is the Global Repository of Income Dynamics, which focuses on using administrative data on earnings and includes micro statistics on income inequality and income dynamics at the individual level for 13 countries using administrative records data on earnings histories (see Guvenan et al., 2022).

In addition to the international efforts, the U.S. economic statistical agencies, including BEA, BLS, the Statistics of Income Division of the Internal Revenue Service, the Census Bureau, and the Federal Reserve Board’s Division of Research and Statistics, have under way or are planning important initiatives to improve their ICW data series (see StatsPolicy.gov for data initiatives). Examples include BEA with its distributional household personal income statistics; BLS with its planned improvements to the Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE), plans to develop consumption statistics in addition to expenditure statistics, and joint efforts with BEA to develop household distributions of PCE; the Federal Reserve Board’s Distributional Financial Accounts and a collaborative effort to tie personal income and wealth (via the Distributional Financial Accounts and the SCF; and the Census Bureau’s efforts to improve the quality of its household income data. These agency efforts also include comparisons across survey estimates—for example, CPS-ASEC to Personal Income at BEA (Rothbaum, 2015); PCE to CE consumption expenditures (Wilson, 2018); SCF to Survey of Income and Program Participation for wealth estimates (Eggleston & Klee, 2016); CPS-ASEC to CE income (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023); and an

___________________

19 See wid.world/

extensive study funded by the Department of Health and Human Services comparing income across eight surveys (Czajka & Denmead, 2008).

While some of these initiatives are cooperative endeavors among agencies, they are not generally being developed with full interagency coordination. Consequently, problems of inconsistent concepts and other features are likely to persist without a sustained effort to understand inconsistencies as well as the strengths and weaknesses of each data source, and without taking the necessary steps to facilitate transparency, harmonization, and integration. Steps are needed as well to address legal and regulatory barriers to cooperative efforts.

THE GOALS OF THIS REPORT

This panel and its work build on the efforts of U.S. statistical agencies and international organizations and are part of a larger effort of CNSTAT to expand the nation’s data infrastructure and use of blended data in federal statistics. The CNSTAT report, Toward a 21st Century National Data Infrastructure: Mobilizing Information for the Common Good, states (in National Academies, 2023a, Conclusion 2-1, p. 35):

The United States needs a new 21st century data infrastructure that blends data from multiple sources to improve the quality, timeliness, granularity, and usefulness of national statistics, facilitates more rigorous social and economic research, and supports evidence-based policymaking and program evaluations.

Two additional reports on 21st century data infrastructure both conclude that the current national data infrastructure, with its reliance on the federal statistical system and statistical surveys, cannot meet the data needs of the 21st century. They recommend evaluating options for producing blended data from multiple sources and studying issues of researcher access. To meet the demands for credible, trustworthy, and timely statistical information, a new data infrastructure is needed (see National Academies, 2023a,b).

This push for a 21st century infrastructure was also a theme in a recent National Bureau of Economic Research volume, in which Abraham et al. (2022, p. 4) state in their introduction: “Our hope is that, at the point when the American economy experiences any future crisis, the statistical agencies will be prepared to make use of the ongoing flow of Big Data to provide information that is both timely and comprehensive to help with guiding the important decisions that policy makers will confront.” This theme of needing a 21st century data infrastructure is forefront in many recent data infrastructure reports. For example, Abraham (2022), Abraham et al. (2022), Jarmin (2019), and others stress the importance of working

with federal agencies and the importance of blending data (also see Jarmin & O’Hara, 2019).

This report builds on those efforts to recommend and design a data infrastructure for the 21st century. As articulated in the charge to the panel provided at the beginning of the chapter, the goal of this report is to provide a comprehensive review of federal income, consumption, and wealth statistics and data sources and make recommendations on building a 21st century data infrastructure for ICW data that produces new consistent estimates and data that can be used for both research and policy. Examining the causes and policy options to address economic inequality and other aspects of economic wellbeing for households at different points in the distribution would be made much easier by the existence of an integrated data source on the changing levels and distribution of household income, consumption, and wealth, compiled from multiple data sources, including surveys, administrative records, commercial data, and the national accounts.

The path forward will be led by researchers and agency staff, who have the expertise to develop a new data infrastructure and improve the statistics released by the agencies on the distributions of income, consumption, wealth, and savings. This combination of integrated data and new statistics will inform the public, the media, and policy makers. Reflecting the broad interest in data and statistics for measuring inequality and policy impacts on inequality, this panel was funded by multiple foundations (i.e., California Community Foundation, The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Omidyar Network, the Spiegel Family Fund). Likewise, many agencies and other stakeholders participated in the panel’s open meeting discussion.

At the initial meetings, the panel recognized that the issues in its charge revolved around five key topics: defining consistent (and appropriate) measures of ICW, constructing new statistics and their distributions by population groups and geography, assessing data quality and determining the ideal ICW dataset, blending multiple datasets to construct a new ICW data infrastructure, and assessing the tradeoffs of confidentiality protection and access to the new data. As a result, the panel created five subgroups to separately address these topics, and structured public meetings to gather information on the current methods used (both in the United States and internationally) and possible new methods. While the expertise of panel members spanned all of these topics, members agreed they needed more information about the current data and methods used by federal agencies, researchers, and international statistical offices, alternative administrative and commercial data, and the challenges in blending multiple data sources.

During a planning meeting in May 2021, sponsored by the Omidyar Network, and during the panel’s open meetings, the panel heard from 35 experts, 18 agency representatives, and 6 international statistical

organizations, with discussion and public participation (see participants in open meetings in the Acknowledgements). In the first open meeting of the panel, three leaders in the measurement of inequality (and all National Academies members)—Raj Chetty, Angus Deaton, and Emmanuel Saez—were asked to provide initial suggestions of paths to follow based on their research and on the panel’s charge. Chetty called for improving mobility estimates, Deaton for consistency across measures, and Saez for using microdata to evaluate macro trends. While they mostly focused on income inequality, all three agreed that income measures alone were not sufficient. In fact, Chetty stated that a new data infrastructure is needed, with wealth and consumption in addition to income, in order to better understand changes in social and economic mobility. Deaton suggested that all three are needed to assess the inconsistencies in any one index. Saez, focusing on the distribution of national accounts, also endorsed a new data infrastructure, one that would support federal agencies in producing these new distributions (see Chetty, 2022; Deaton, 2022; Saez, 2022).

The public meetings focused on gathering information about current efforts at the federal agencies in constructing ICW statistics with the addition of an entire meeting on international efforts. Specific meeting sessions addressed the issues in measuring retirement income and health insurance benefits and methods for estimating wealth. Two meetings focused on the possibilities of using tax data blended with survey data, while another meeting examined how to use commercial data together with administrative and survey data. In a final set of sessions, the panel learned about creating synthetic data and approaches to managing access to complex data infrastructures.

Through these meetings, coupled with panel member expertise and discussions, in response to the charge, the panel agreed that an integrated dataset is needed that can support timely estimates released at least annually, microdata for research and policy analysis, joint distributions of ICW, and differences by groups. The federal statistical system can produce consistent measures and identify standard series that can provide frequent, timely estimates of household ICW with needed detail. While there is no single measure that can be used for all purposes, the report discusses a specific set of measures that would be useful for research and policy. In addition, the microdata need to be accessible by both agency staff and outside researchers for their use conducting research and evaluating policy options. The panel acknowledges that not everything can be included in one dataset; multiple datasets may be required, each for a different purpose, and therefore they need to be linked.

The panel heard about ongoing agency cooperation to improve estimates and the progress already made. Working within a set of constraints,