An Assessment of Selected Divisions of the National Institute of Standards and Technology Information Technology Laboratory: Fiscal Year 2024 (2025)

Chapter: 5 Computer Security Division

5

Computer Security Division

The Computer Security Division (CSD) concentrates on near-term issues. That is, it deals with existing problems or issues reasonably believed to be likely problems in the foreseeable future. This does not imply that the solutions are easy or obvious or even “mere” engineering. Not only are deep insight and creativity needed to solve these problems, but a fair amount of political and interpersonal skill is needed to get these solutions accepted and, in some cases, even developed.

The panel received presentations on CSD as a whole and on a number of different projects being carried out within the division. The latter include groups working on cryptographic technology, security test validation and measurement, security components and mechanisms, secure systems and applications, post-quantum cryptography (PQC), trustworthy artificial intelligence (AI), the National Vulnerability Database, cryptographic module validation, protection of unclassified information, lightweight cryptography (LWC), hardware security, security guidance for microservices-based architectures, and risk management frameworks.

Not every project presented to the panel is discussed in the report. Only those projects about which the panel had comments are discussed.

ASSESSMENT OF TECHNICAL PROGRAMS

Accomplishments

Cryptographic Technology Group

Over the past 10 or so years, cryptographic technology has been a growth area for CSD. Apart from the need for new standards, such as for post-quantum algorithms, in response to past situations where a lack of in-house cryptography expertise was a problem CSD has significantly strengthened the cryptography expertise resident on staff. CSD now has adequate cryptography expertise on staff, and the division has established its credibility in this area of expertise, most recently culminating in the hosting competitions in post-quantum cryptography and light-weight cryptography.

The Cryptographic Technology Group is doing work that is probably without peer in the world. Its algorithms, although technically required only for unclassified U.S. government systems, are more widely used than any competing national or international standards, including within the European Union, which often has its own equivalents. Many of the products of this group, such as the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) and the newest version of the Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA), have been products of open, worldwide competitions. It is notable that the winners of these competitions that have since been standardized—AES and SHA-3—were algorithms submitted to the competition by Europeans.

Other major work areas for the cryptography technology group include PQC, zero-knowledge proofs, and modes of operation. Foreign researchers often visit; this is good for establishing links to other national standards bodies.

About half of the staff of the Cryptographic Technology Group is working on PQC algorithms, algorithms that are designed to be resistant to attack by future quantum computers. The ongoing PQC program is a jewel in the Information Technology Laboratory’s (ITL’s) crown. The deliberate

establishment of in-house mathematical expertise; the open, transparent, and fair competition; the measured pace; the curation of community; and the professionalism of the project management have all combined to form a widely supported and successful cryptographic algorithm competition. All currently used public-key algorithms, including Rivest-Shamir-Adleman (RSA), Diffie-Hellman, and the elliptic curve equivalents, will be vulnerable to attack by quantum computers once powerful enough quantum computers—that is, ones with a sufficient quantity of quantum bit-equivalents (qbits)—are built. While it is not clear when such computers will become practical, a lot of existing data will need to be protected for many years, perhaps decades. Accordingly, there is an urgent need for new PQC algorithms now, to guard against forged signatures and decryptions of recorded traffic in the future.

CSD responded by hosting a competition to develop PQC algorithms. As with all CSD’s cryptographic competitions, this one started with a statement of requirements and an open call for public submissions. There followed a sequence of public workshops to discuss the various submissions, followed by an evaluation of each candidate algorithm in light of the research results attacking or supporting each remaining candidate PQC algorithms. At the conclusion of each round of the evaluation, some candidate algorithms were dropped and others were passed on to the next round for further consideration.

As of the panel’s review, the PQC competition had completed five rounds and was almost done. It is considered relatively high risk because the criteria for creating and attacking post-quantum cryptographic algorithms are not as well developed as for older, pre-quantum technologies. CSD has dealt with this by selecting backup PQC algorithms, in case an unforeseen attack should be developed later. The current surviving candidates all appear to have strong support worldwide.

This ongoing work, along with the unpredictable pace of adversarial technology and mathematical developments, means that ITL will have to remain capable in PQC matters for some time to come.

Traditional cryptographic algorithms like AES are often too resource-intensive for devices with limited computational power, memory, and energy resources. Despite these constraints, such devices still require strong security measures to protect sensitive data and ensure privacy and integrity.

LWC is intended for resource-constrained devices such as smart home devices, connected cars, smart cards, radio frequency identification tags, pacemakers, and Internet of Things (IoT) devices. CSD has initiated the LWC Standardization Process, an open competition, similar to the SHA-3 and the much older AES competitions, to address the growing need for cryptographic standards tailored to constrained environments.

CSD announced a LWC competition in 2018. The competition aimed to identify and standardize lightweight cryptographic algorithms that could provide adequate security and resource efficiency for resource-constrained environments and promote research and development in the field of LWC. It consisted of multiple rounds, each involving rigorous analysis by CSD and the cryptographic community, leading to a progressively narrower selection of candidates. Public workshops, conferences, and comment periods allowed for broad community involvement. The competition concluded with the selection of the Ascon family of algorithms as the standard for LWC applications and the decision was announced in February 2023. This competition represents a significant effort to address the unique security needs of resource-constrained environments by fostering innovation and rigorous evaluation. The competition’s outcomes have far-reaching implications for the security of IoT devices and other applications where traditional cryptographic algorithms are impractical.

Security Testing, Validation, and Measurement Group

The Security Testing, Validation, and Measurement Group focuses on developing, implementing, and promoting security standards and guidelines. This group is instrumental in ensuring the security and reliability of information systems through rigorous testing, validation, and measurement techniques. Its activities can be listed in the following five sub-categories:

- The Cryptographic Module Validation Program validates cryptographic modules to ensure they meet the Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) and other National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) standards. This program aims to ensure that cryptographic modules used in federal systems are secure and comply with standards such as FIPS 140-2 and FIPS 140-3, both titled “Security Requirements for Cryptographic Modules. These modules are validated by laboratories accredited by CSD and the National Voluntary Laboratory Accreditation Program.”1 ITL is resourced by the laboratories and the National Voluntary Laboratory Accreditation Program to support this activity.

- The Cryptographic Algorithm Validation Program provides validation testing for cryptographic algorithms to ensure they are implemented correctly. Its scope includes all NIST-approved algorithms including AES, SHA, RSA, Digital Signature Algorithm, and elliptic curve cryptography.

- The Security Content Automation Protocol is a suite of specifications used to automate vulnerability management, vulnerability measurement, and policy compliance evaluation. This protocol helps organizations manage security risks by automating the process of checking systems against security policies and configurations. Its components include standards such as Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures, Common Configuration Enumeration, and eXtensible Configuration Checklist Description Format.

The activities of the Security Testing, Validation, and Measurement Group are crucial for ensuring that cryptographic products and algorithms used in government and industry meet stringent security standards, providing a framework for continuous improvement in security practices through rigorous testing and validation, and promoting interoperability and reliability in security technologies across different sectors.

Security Engineering and Risk Management Group

Standards and guidelines developed and published by the Security Engineering and Risk Management Group help to improve the security of information systems. Examples are FIPS publications, NIST Special Publications such as SP 800-53, “Security and Privacy Controls for Federal Information Systems and Organizations,” and SP 800-57, “Recommendation for Key Management.”

Security Components and Mechanisms Group

The Security Components and Mechanisms Group is involved in several key initiatives aimed at system security, metrology, emerging technologies, and cybersecurity management. The key achievements listed in the group presentation are all in areas of AI—specifically,

- Trustworthy AI,

- Taxonomy of attacks and mitigations in AI,

- AI models used in autonomous vehicles, and

- Measuring and evaluating the efficacy of AI.

As part of its AI activities, the Security Components and Mechanisms Group has

___________________

1 The National Voluntary Laboratory Accreditation Program is part of the NIST Standards Coordination Office in the Associate Director for Laboratory Programs Office. It accredits laboratories to perform specific tests and calibrations, including those related to cryptographic module testing, ensuring that laboratories meet the necessary qualifications to conduct rigorous and accurate testing. For CSD, it accredits laboratories that support the Cryptographic Algorithm Validation Program.

- Developed the Secure Software Development Framework in support of Executive Order 14110, “Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence.”

- Developed the new NIST AI 100-2 E2023, “Adversarial Machine Learning: A Taxonomy and Terminology of Attacks and Mitigations,” which was widely adopted across industry, media, and governments and has been the basis for the upcoming standard AI 100-2A.

- Developed an “eye test” for computer vision models.

- Developed an AI measurement and evaluation platform.

In addition to AI-related activities, the Security Components and Mechanisms Group has also developed SP 800-223, “High-Performance Computing Security: Architecture, Threat Analysis, and Security Posture,” in support of Executive Order 13702, “Creating a National Strategic Computing Initiative.” Another important contribution of the Security Components and Mechanisms Group is the development of FIPS 201-3, “Personal Identity Verification (PIV) of Federal Employees and Contractors.”

Secure Systems and Applications Group

The Secure Systems and Applications Group has been focusing on attribute-based access control. This is a reasonable idea, but the concepts are at least 25 years old. Although attribute-based access control has been widely adopted by industry over the years, it is unclear where the market is today. This group has leveraged its strong past success in attribute-based access control to develop novel and advanced access control solutions. They have extended their expertise to support access control in zero-trust architecture: standards-based access control is not currently supported in existing products. It is a gap in industry because it requires integration across different components of zero-trust architectures, but different vendors have different strategies. Vendor lock-in is the strategy for large providers, so they have little incentive to build systems with open architectures where components can be replaced by those from other vendors, while acquisition by a larger vendor is the strategy of small ones. Government work in this zero-trust gap is directly applicable to Executive Order 14028, “Improving the Nation’s Cybersecurity,” and is not in competition with anything industry is pursuing. In addition, the Secure Systems and Applications Group has found a technology transition partner, which positions them well to be the leaders in standards of integration in this zero-trust gap area. However, owing to vendor strategies, it is not entirely clear how much impact the effort on the zero-trust initiatives will have nationally and internationally. The service mesh work presented did not include any metrics for success.

National Vulnerability Database

The National Vulnerability Database (NVD) is one of the key programs presented to the subpanel. From a technology development perspective, the NVD program has been a great success, in large part owing to the leadership provided by the federal employees assigned to the program. That said, it is a crucial security resource that is consuming a significant amount of resources, largely for Amazon Web Services fees for making the data available. These costs are likely unsupportable in light of the limited resources available to CSD.

Today, the NVD can be accessed by a legacy database download method and an application programming interface (API). The database download is an old and expensive method—users have to transfer everything, rather than just what they need. The API is less expensive to operate. CSD is trying to move away from the legacy database download method to using only API access but has been unsuccessful in doing so to date. It was reported to the panel that what is lacking seems to be a decision to finally make the change.

Recommendation 5-1: To increase security, automate as much of the workload as possible, and reduce operating costs, the Computer Security Division should migrate access to the

National Vulnerability Database to an application programming interface as rapidly as possible.

Security Guidance for Microservices-Based Architectures Group

The Security Guidance for Microservices-Based Architectures Group develops security architecture standards. It operates at a much lower functional level and so does not use the access control framework being developed by the Secure Systems and Applications Group. Companies regularly claim that their chips are resistant to hardware, or side-channel, attacks, but there are no common criteria for judging the resistance. The private sector is unlikely to achieve consensus on any common criteria or standards because they will develop and market product-specific security architecture standards to highlight their particular security features. ITL’s and CSD’s work in this area provides an independent and trusted security architecture standard to which industry can conform, increasing confidence in the security of hardware.

Opportunities and Challenges

The Security Components and Mechanisms Group is doing excellent work, but their scope may be too ambitious for the available resources.

It might be useful for the Security Guidance for Microservices-Based Architectures Group to use competitions, like those for PQC and LWC, to prompt the development of security architecture standards.

It is not entirely clear what criteria are used to define projects or how projects are prioritized. It is also not clear how CSD decides that a project has been successful and should be retired. CSD is overcommitted and, especially in light of the budget discussion below, does not have the resources to continue its current suite of projects at sufficient depth to lead to groundbreaking results. Also, some groups do not seem to understand the larger purpose of their work nor how it fits into the larger CSD vision, although CSD leadership does seem to understand this. More coordination, closer mentoring, and cross-group interaction would be helpful. There also appears to be a need for strategic planning of work to intentionally consider what projects should be pursued with CSD’s very limited resources, how they fit into CSD’s mission, and when projects ought to be retired in favor of new work.

Recommendation 5-2: The Computer Security Division (CSD) should engage in a strategic planning process to intentionally choose projects that align with its mission and make the best use of the division’s extremely limited resources. This plan should also consider when projects have been successful and what projects ought to be retired to free up resources for new work. This plan should be clearly communicated to all CSD staff so that they understand exactly how their work fits into the broader divisional mission.

The Cryptographic Module Validation Group publishes a list of validated modules, but not in a form that can be easily parsed by machine. This limits the impact of this list. CSD has a portfolio of programs that started at low volumes and were supported manually. Examples are the NVD and the Cryptographic Module Validation Program. Each of those programs has seen wide adoption. The volume of work has increased to outstrip the resources available, resulting in unacceptably long wait times for validation and compromising their value to users and the nation. The challenge is to operate at scale through advanced planning for success, timely development of automated processes, and resourcing the appropriate mix of staff skills. The skills necessary to conceive and create a program are generally different from the skills necessary to sustain it and operate it at scale. There is an opportunity to free the creators from a successful program so that they are available to create new things. In short, CSD excels at developing technologies, but ought not be an operational agency. Once a technology has been developed, it is advisable to hand it off to someone else to operate, such as contractors who specialize in operations versus research and creation. This has been done successfully with cryptographic module validation but not with the NVD.

SOURCE: Courtesy of NIST Information Technology Laboratory.

Recommendation 5-3: To free up staff and financial resources for new work, the Computer Security Division should hand off developed technologies to others such as contractors to operate. This will allow researchers to focus on what they are good at and put operations in the hands of those who are skilled at it.

CSD provides several free public goods whose provision might be monetized to create revenue streams and offset costs, reducing financial stresses (see the section “Budget,” below). These goods include patent licenses and access to online services, including the wildly successful NVD and the Cryptographic Module Validation Program. Much as other NIST laboratories charge for standard reference materials and reference data sets, perhaps CSD could charge commercial organizations that build commercial products on top of the NVD some fee for using the service, helping to offset some of the costs associated with maintaining this database. Individual and noncommercial access to the NVD, however, would need to remain free. It is advised that cost recovery for commercial use of such services be aggressively computed to include not only computing and storage but also the fully burdened staff costs of creating, automating, and providing these services.

ASSESSMENT OF SCIENTIFIC EXPERTISE

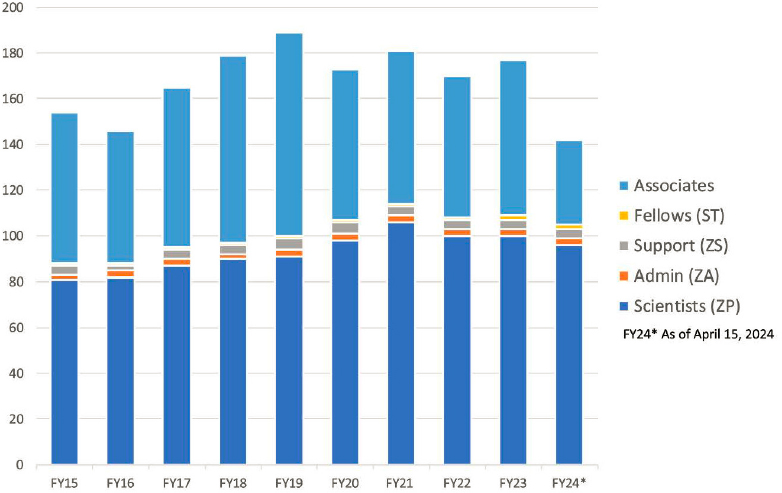

As of May 2024, CSD had 140 staff. There are 86 scientists, 44 associates, 2 fellows, 5 support staff, and 3 administrative staff.2 Figure 5-1 shows CSD staffing levels and composition from fiscal year (FY) 2015 through April 15, 2024.

___________________

2 Associates are not NIST employees. They are outside researchers, both foreign and domestic, who collaborate with NIST researchers.

Accomplishments

The quality of the CSD staff is reflected in the wide range of professional awards and honors they have received. A sampling includes

- Department of Commerce Gold Award

- Department of Commerce Silver Award

- Women in Technology Rising Star Award

- Washington Academy of Sciences Distinguished Career Award in Computer Science

- 2023 NIST George A. Uriano Award

- 2023 IEEE International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation Most Influential Paper Award

- Washington Academy of Sciences fellow

The CSD staff are generally world-class in their areas, leading cutting-edge work. For example, the Cryptographic Technology Group organizes and leads open competitions for cryptographic algorithms, including PQC. These competitions attract wide participation from academia and industry. The entrants present their solutions while critiquing the entries of others. The arguments on all sides are deeply technical and mathematical. CSD staff sort through all this using their organic expertise to reach sound and defensible decisions. These lead to standards that form the basis for secure communication worldwide in support of internet access, e-commerce, wireless infrastructure, and personal privacy. The staff are go-to experts in their areas.

The group working on access control issues is similarly well respected. Their work on biometrics, and in particular their measurements of accuracy and bias in various algorithms, plus their standard data set, are used worldwide. Their newer work on attribute-based access control holds great promise for the future: it is one of very few implementations of the concept, and their algorithm and programs for converting attribute graphs to industry-standard access control lists make the work extremely portable and valuable. Similarly, the extension of attribute-based access control to cloud and zero-trust architectures will be extremely valuable.

In general, CSD does not have any obvious gaps in the expertise represented by its staff. CSD generally hires staff to meet expertise needs. Any of them could easily find a job in industry and NIST is fortunate to have them.

Opportunities and Challenges

The CSD staff is expanding to meet the security needs of the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 (P.L. 117-167). There is an opportunity to expand the cryptography acceleration and side-channel analysis team with new expertise and staff.

BUDGET, FACILITIES, EQUIPMENT, AND HUMAN RESOURCES

Budget

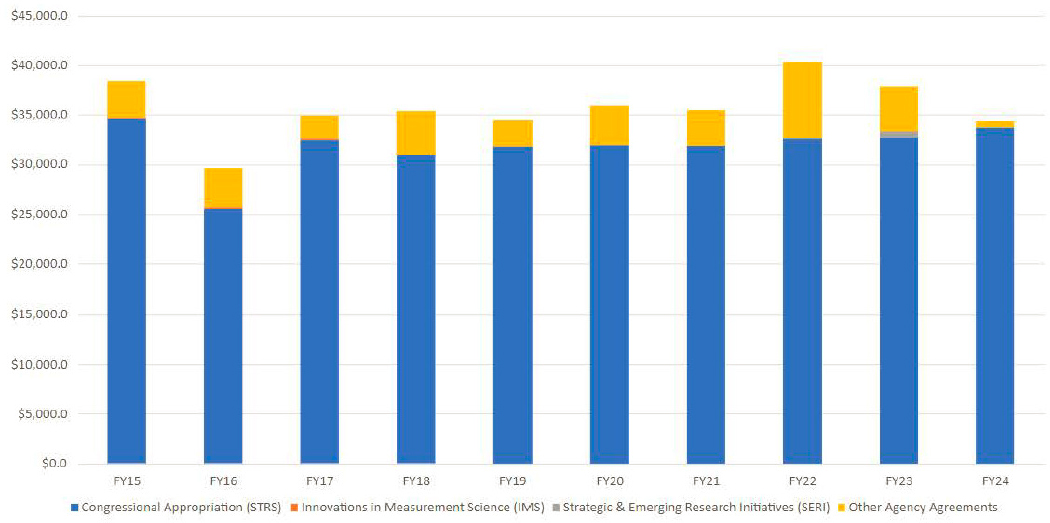

CSD’s budget from fiscal year (FY) 2015 through FY 2024 is shown in Figure 5-2. STRS is the scientific and technical research services appropriation that funds the laboratory’s technical work. Innovations in Measurement Science is an internal NIST grant program to fund work to advance metrology. The Strategic and Emerging Research Initiatives program is an internal NIST effort to fund work to perform research studies to identify issues and opportunities in measurement science, trustworthiness, and innovation. Other agency agreements represent reimbursable work done for other federal agencies.

NOTE: STRS, scientific and technical research services.

SOURCE: Courtesy of NIST Information Technology Laboratory.

SOURCE: Courtesy of NIST Information Technology Laboratory.

As can be seen, the budget has fluctuated holding largely at around the $35 million level for most years in this span. The budget for FY 2024 is $4 million less than that for FY 2015, so there has been a real decrease in the budget over this time. It is important to note that these numbers are not corrected for inflation, so it is very likely that CSD has lost ground in its budget over the past decade.

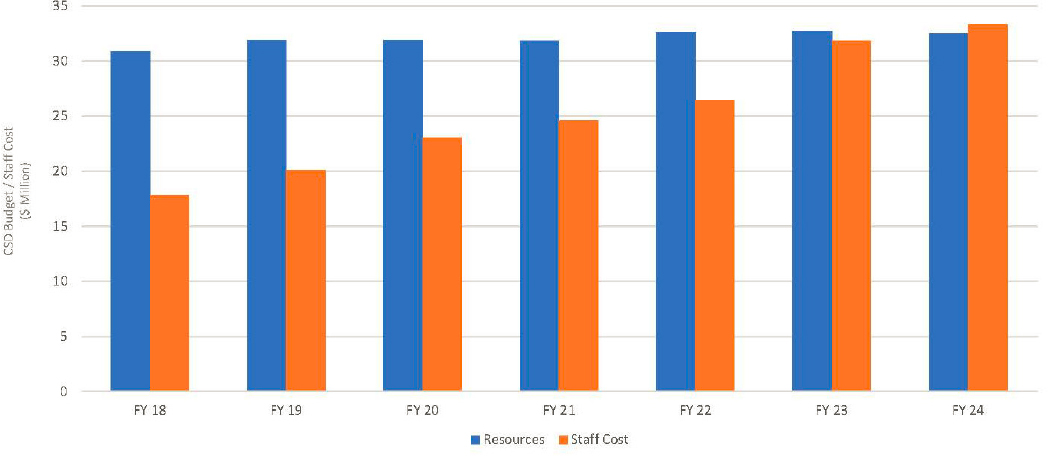

The budget picture, however, becomes bleaker when the CSD budget is compared with the salary growth of its staff. Staff members usually receive annual raises, and some NIST laboratories have adjusted salaries to make them more competitive with the private sector. Figure 5-3 shows how staff costs have grown compared with CSD’s baseline congressional appropriations between FY 2018 and FY 2024. The costs are for full-time equivalents only.

The relatively flat budgets over the past decade, inflation, and the growth in staff costs taken together mean that CSD faces a budget crisis. Its budget has been flat or declining in recent years, and as a consequence recruitment has been hard of late. Congressionally allocated funds no longer cover even the raw staff costs. Travel, which is necessary to establish and maintain relationships to influence standards, is no longer funded. Contractors, who are required to operate successful programs at scale, are no longer funded. Student intern programs, necessary to build the workforce, are no longer funded. CSD’s work is not sustainable at current levels of funding.

Facilities and Equipment

Unlike most other NIST laboratories, ITL does not require facilities with precise environmental controls or a wide range of expensive and sensitive equipment. ITL does need computers and server rooms with proper environmental controls. CSD has these. The panel noted no deficiencies in the facilities or equipment that CSD uses.

Human Resources

The main human resources challenge facing CSD is the aging workforce. Many people are retirement-eligible or will be soon. Morale is generally high, and many people stay well past retirement. But the problems caused by inadequate resources vis-à-vis hiring new staff as discussed earlier in the section “Budget” cannot be underestimated. A consequence of this is the lack of a deep bench; the senior staff are excellent but do not have adequate backup because of the inability to hire newer junior staff.

If, as CSD is contemplating, they institute a retirement incentive program to cut salary costs, this will result in a skill gap and a lack of mentoring for junior staffers. They have tried to compensate for the lack of senior people by bringing in external speakers, often via Zoom, and by having internal seminars, but this is unlikely to be enough: outsiders cannot provide sufficient mentoring. The situation calls for careful succession planning to balance costs and benefits in a workforce transition.

EFFECTIVENESS OF DISSEMINATION EFFORTS

CSD is getting its message out to its stakeholder communities. Between January 2018 and May 2024, the number of subscribers to its products grew, sometimes substantially. For example, the increase in the following subscribers was

- Draft publications: 31 percent

- Federal Information Processing Standards: 21 percent

- Federal Information Systems Management Act News: 192 percent

- Risk management–related publications: 190 percent

- NIST Cybersecurity Events: 115 percent

- NIST Internal Reports: 24 percent

- Special publications: 15 percent

Computer Security Resource Center use has seen the following growth between 2018 and 2023:

- Total sessions: 133 percent

- Total users: 193 percent

- Users per day: 193 percent

- Page views: 112 percent

- Publication details (page views): 90 percent

- Cryptographic Module Validation Program validations (certificate page views): 190 percent

CSD has published 93 new final reports since January 1, 2018. CSD has hosted 16 conferences and workshops since 2018, including 6 on PQC, 4 on LWC, 3 on threshold cryptography, and 2 on modes. They have ongoing seminars: the Crypto Reading Club, the PQC Seminar Series, and Privacy and Auditability. In addition, CSD participates in the Internet Engineering Task Force; the International Organization for Standardization and the International Electrotechnical Commission Subcommittee 27 on Information Security, Cybersecurity, and Privacy Protection; the Trusted Computing Group; and the Bluetooth Special Interest Group.

Also since 2018, CSD staff have authored

- 33 conference papers,

- 23 journal articles,

- 18 book chapters, and

- 23 preprint papers.

ITL groups state their accomplishments in terms of outputs (e.g., number of papers, number of patents, number of meetings convened) rather than in terms of outcomes (e.g., impacts on U.S. commerce, dollar size of the ecosystems they support, or number of times a standardized algorithm is used per minute). Outputs are easier to measure than outcomes, but they are not impressive to appropriators. ITL would be well served to quantify and describe its support of U.S. industry, and to collect and tell industry use case stories when dealing with legislative staff. Similarly, concerning ITL’s massive support of federal agencies, it would be advantageous to collect and tell use case stories rather than simply recite the number of publications produced.

As an example of measuring outcomes, NIST maintains a webpage titled Outputs and Outcomes of NIST Laboratory Research (created on July 20, 2009, and last updated on June 2, 2021, so this is only an example). It lists the economic impact of selected NIST research efforts. ITL has four listings on this webpage:

- 1995: Interoperability standards for Integrated Services Digital Network leading to lower transaction costs: social (internal) rate of return of 156 percent.

- 1995: Acceptance test methods for software conformance leading to lower transaction costs: social (internal) rate of return of 41 percent.

- 2001: Standard conformance test methods and services for data encryption standards: social (internal) rate of return of 267–272 percent; a benefit–cost ratio ranging from 58 to 145; and net present value ranging from $345 million to $1.2 billion.

- 2001: Generic technology reference models for role-based access control enabling new markets and increasing research and development efficiency: social (internal) rate of return of 44 percent; a benefit–cost ratio of 109; and net present value of $292 million. (NIST 2021)

Recommendation 5-4: The Computer Security Division should explore and develop metrics that measure the impact and outcomes resulting from its work rather than simply counting outputs.

REFERENCE

NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology). 2021. Outputs and Outcomes of NIST Laboratory Research. https://www.nist.gov/director/outputs-and-outcomes-nist-laboratory-research.