Exploring Linkages Between Soil Health and Human Health (2024)

Chapter: 2 The Connectivity of Health

2

The Connectivity of Health

The interdependence of the health of humans, other animals, and ecosystems has long been apparent. The written record includes observations by Hippocrates and Aristotle of the connections between human health and the health of the environment and between human disease and that of other animals, respectively (Evans and Leighton 2014). In the past three centuries, the recognition that maintaining health in humans, other animals, and ecosystems “constitute[s] a single objective, because to achieve all three at once is the only means of achieving any one of them” has steadily gained traction in academic, scientific, and political institutions (Evans and Leighton 2014, 414). Over the course of the 20th century, increasing awareness among scientists, conservationists, and policymakers of the need to address health collectively and holistically resulted in a series of meetings in the late 1990s and early 2000s that led to the coining of the term One Health in 2004 (Cook et al. 2004; Gibbs 2014).

One Health has been defined many ways in the subsequent years. In 2021, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH, founded as OIE), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the United National Environment Programme (UNEP) endorsed the following interpretation of the concept:

One Health is an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals, and ecosystems. It recognizes the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment (including ecosystems) are closely linked and interdependent.

The approach mobilizes multiple sectors, disciplines, and communities at varying levels of society to work together to foster well-being and tackle threats to health and ecosystems, while addressing the collective need for healthy food, water, energy, and air, taking action on climate change and contributing to sustainable development. (OHHLEP 2022, 2)

This definition captures the multitude of organisms whose health needs to be maintained. It also acknowledges the importance of the health of Earth itself, as functional Earth processes are fundamental to sustaining an environment that can support life with clean water and air and with an adequate food supply.

Attention to the health of Earth—to local, regional, and planetary environmental systems—within the pursuit of One Health is overdue (Barrett and Bouley 2015). In 2010, FAO, WOAH, and WHO came together to publish a Tripartite Concept Note that proposed “a long-term basis for international collaboration aimed at coordinating global activities to address health risks at the human-animal-ecosystems interfaces” (FAO, OIE, and WHO 2010). Although ecosystems were mentioned, the document and subsequent work of the three organizations focused heavily on the control of diseases, especially diseases that move from animals to people (Gibbs 2014). It was only in 2022 that UNEP joined the others to establish the Quadripartite Collaboration for One Health, “reaffirming the importance of the environmental dimension of the One Health collaboration” (FAO et al. 2022, 1). That year, the Quadripartite Organizations published a joint plan of action “to drive the change and transformation required to mitigate the impact of current and future health challenges at the human–animal–plant–environment interface at global, regional and country level” (FAO et al. 2022, x).

Integrating the environment into One Health is one of the six tracks within the action plan. In the plan, the Quadripartite Organizations acknowledge that:

The environmental sector, which consists of areas such as natural resource management, wildlife management and conservation, biodiversity conservation, management and sustainable use, pollution and waste management, is not always routinely incorporated into the One Health approach and there has been limited engagement in cross-sectoral initiatives. The role of the environmental determinants of health has not been well understood by other sectors and there is good potential to integrate environmental considerations more consistently. (FAO et al. 2022, 11)

Of the many poorly understood and unintegrated components of “the environmental sector,” perhaps the most neglected among them is soil (Singh et al. 2023). When it comes to the effect of soil on the health of other organisms, the joint plan of action only discusses the need to address chemical contamination of soil. Yet, the biological, chemical, and physical health of soil is integral to the balanced and optimized health of people, other animals, and ecosystems beyond just the mitigation of contaminants. Leonardo da Vinci is credited with saying “We know more about the movement of celestial bodies than the soil underfoot,” an observation that is still true five centuries later. This chapter briefly describes the fundamental role soil plays in the pursuit of One Health and the impact land use change has had on soil’s ability to contribute to One Health objectives. It then describes the properties of soil that define soil health. Components of the definition of human health are also reviewed. The importance of microbiomes as a conduit between soil health and human health are highlighted in the last section.

SOIL AND ONE HEALTH

Attention to the state of soils is essential to the objectives of One Health. Healthy ecosystems cannot exist without soils that successfully contribute to Earth’s

biogeochemical cycles, which move the atoms of key elements between living and nonliving things and make life possible. Many of these cycles are reliant on the organisms that live in soil. People, other animals, and plants depend on the products generated by these cycles and organisms (see Chapter 3 for further discussion). When these cycles are functioning properly, soil and the organisms that live in it contribute to the One Health objectives of optimizing the health of all organisms while supplying clean air and water and supporting the production of food.

However, the state of soils today suggests that their ability to contribute to One Health objectives is impaired. It is estimated that at least 15 percent of Earth’s land surface suffers from human-induced soil degradation, largely caused by erosion, nutrient loss, salinization, pollution, and compaction (Oldeman et al. 1991). Much of that degradation is due to the conversion of wildland from native ecosystems into managed agricultural systems (Box 2-1).

The global pattern of conversion holds true for the United States. Between the 1780s and 1980s, more than 50 percent of the wetlands in the conterminous United States were lost, mostly due to agricultural conversion (Dahl 1990). The loss of wetland soils’ contributions to One Health—for example, the cleaning of water through filtration—has been amplified by other degradations linked with agricultural production. The excess application of nitrogen to U.S. agricultural fields increases crop yields but directly works against the One Health objectives of clean air and clean water by contributing to air and water pollution (Ribaudo et al. 2011). Soil’s fertility—that is, its part in addressing the collective need for healthy food—as well as its ability to serve as a filter for contaminants can be altered by the accumulation of pesticides, metals, plastics, and other compounds (Wang et al. 2022; Rashid et al. 2023).

Although U.S. agriculture continues to provide abundant food, the degradation of U.S. agricultural soils due to erosion, compaction, biodiversity loss, mineralization of soil organic matter, and contamination has highlighted the urgent need to ensure that soil function is maintained for food production and other One Health objectives. The next section reviews the different properties of soil that contribute to soil function, which, when maintained, defines soil health.

SOIL HEALTH

Terms used to describe the state of soil have proliferated in the field of soil science as researchers and stakeholders have debated definitions that vary in the weight given to static properties versus dynamic ones (e.g., soil texture vs. organic matter content), reflect a point of view (e.g., soil scientist vs. farmer), or place a system of interest in context (e.g., agricultural vs. unmanaged) (Bünemann et al. 2018; Lehmann et al. 2020). The committee uses the term soil health as it is the term in current use by the study’s sponsor and the term used in the statement of task.

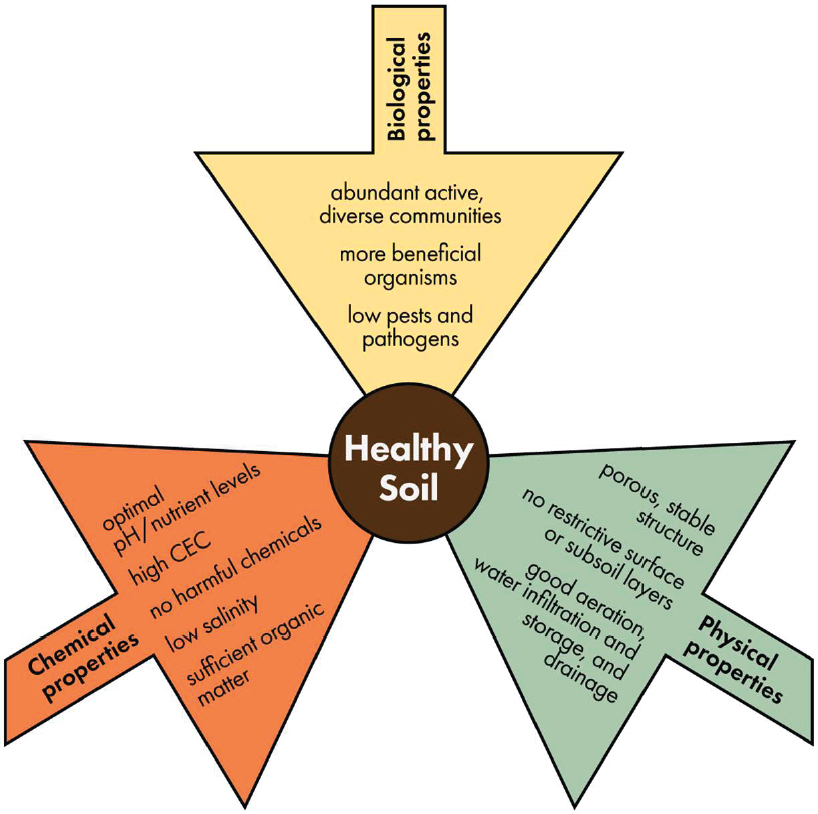

FAO defines soil health as “the ability of the soil to sustain the productivity, diversity, and environmental services of terrestrial ecosystems” (FAO 2020). To achieve this ability, healthy soil should possess important characteristics such as good structure, nutrient availability, water-holding capacity, and biological activity. These characteristics depend on the interaction of a soil’s physical, chemical, and biological properties (Figure 2-2). Soil properties are heavily influenced by the parent material from which the soil

BOX 2-1

Land Use Trends

Land use management regimes—from natural landscapes to managed forests, cropland, and rangeland to urban environments—profoundly influence soil health. On the one hand is the historical and ongoing degradation of soil quality, which threatens to undermine soil ecosystem services critical to One Health such as food production, habitat provisioning, contaminant remediation, climate regulation, and the cycling of nutrients, carbon, and water (see Chapter 3). On the other hand, changes from soil-degrading land uses to those that preserve and protect the soil have the potential to preserve or build soil health and sequester carbon (Guo and Gifford 2002; Lal 2004; Borrelli et al. 2017), holding significant potential to enhance agricultural sustainability and food security and contribute to climate change mitigation (IPCC 2022).

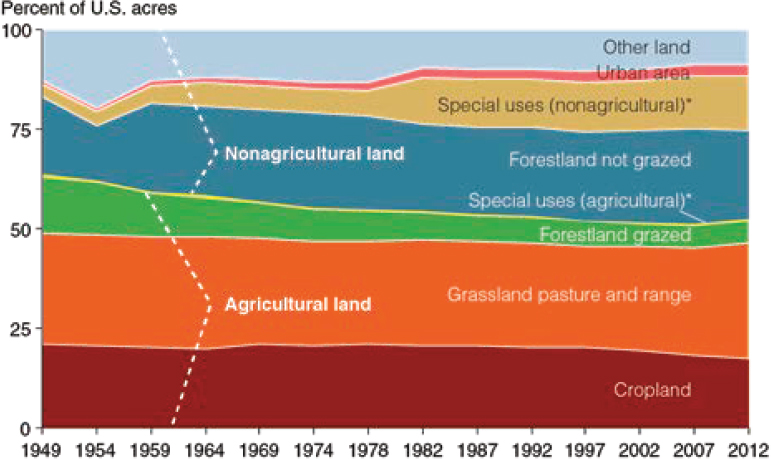

Agriculture is by far the most extensive form of human land management. Currently, over one third of global land area—roughly half of all habitable land on the planet—is used for agriculture (Ellis et al. 2010; Ritchie and Roser 2013; FAO, UNEP, WHO, and WOAH 2022). The same is true for the United States: agricultural use accounts for more than one half of the land (Figure 2-1; Bigelow and Borchers 2017). Conversion of wildland from native ecosystems into managed agricultural systems increased sharply during the 18th–20th centuries both globally and in the United States (Ellis et al. 2010; Klein et al. 2017). Although in recent decades this conversion has slowed or even reversed in some regions of the world (including in the United States), significant expansion of agricultural land continues in some places, notably parts of South America and Africa (Ritchie and Roser 2013; Klein et al. 2017).

NOTE: Special uses include rural parks and wilderness areas, rural transportation areas, defense/industrial lands (all nonagricultural uses), and farmsteads/farm roads (agricultural uses).

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Agriculture–Economic Research Service. “Major Land Uses in the United States, 1949–2012.” Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=58260.

Such historical and ongoing land use change has significant implications for soil health. In temperate regions, conversion from natural to agricultural systems has been observed to cause depletion of the soil organic carbon pool—an important indicator of soil health—by as much as 60 percent, with losses sometimes exceeding 75 percent in tropical regions (Guo and Gifford 2002; Lal 2004). Land use change is also associated with an acceleration in soil erosion and subsequent topsoil loss, with rates of loss from agricultural lands now frequently exceeding natural rates of soil formation, making this a major concern for global food security (Pimentel and Burgess 2013; Borrelli et al. 2017).

Within the broad classification of agricultural land use, management systems vary widely and include cropland, pasture, rangeland, and grazed forest uses. Approximately one third of U.S. agricultural land—392 million acres in 2012—is cropland (Figure 2-1; Bigelow and Borchers 2017). This category of land use is most frequently subjected to tillage, irrigation, and soil amendments, and the intensity of these management practices can vary greatly across cropping systems and have significant bearing on soil health (see Chapter 4). When land use is viewed through the lens of human health—specifically human dietary health—it is notable that the vast majority of U.S. cropland is currently devoted to growing crops such as corn and soybeans used principally for animal feed, yet projections for diets that are both sustainable and healthy indicate a need to reduce the proportion of animal-sourced foods in the American diet while increasing intake of nutrient-rich plant-based foods such as whole grains, pulses, fruits, nuts, and vegetables (Bigelow and Borchers 2017; Willett et al. 2019). Despite the importance of dietary diversity to human health, only 2 percent of U.S. cropland is currently used to grow fruits and vegetables (Bigelow and Borchers 2017; USDA–NASS 2019). Prevailing U.S. vegetable cropping systems are typically high intensity, receiving frequent tillage, irrigation, and relatively high levels of inputs, and managing soil health in such systems presents notable challenges. In combination with their relatively minor land use footprint, there has been a dearth of research and practical management strategies that promote soil health in vegetable cropping systems (Norris and Congreves 2018). Yet, as land used for vegetable cropping increases to support human health via dietary diversity, the soil health of these systems will be of increasing importance, underscoring the connectivity of soil health and human health via land use.

Urbanization is another form of land use change that is important when considering the links between soil health and human health. Urban area accounts for 3 percent of total U.S. land (Bigelow and Borchers 2017). According to the U.S. Census Bureau, as of 2020, 80 percent of the U.S. population now resides in urban areas, which they define as “densely developed residential, commercial, and other nonresidential areas” (U.S. Census Bureau 2022). Urban soils are intensively managed and used for recreation, gardening, and many other purposes, and they provide ecosystem services such as soil filtration (De Kimpe and Morel 2000). Urban soils have distinctive properties, such as higher levels of heavy metal contamination, even in soils within urban forest stands (Pouyat et al. 2008).

formed (e.g., mineral rock or organic matter), the organisms living in the soil, and the topography and climate of the soil’s location as well as the interaction of all these factors over a period of time. Therefore, soil health is highly context dependent.

Soil physical properties include its texture (the size of soil particles) and structure (how closely and in what shape soil particles are bound or aggregated) (Brady 1984). These features relate to a soil’s porosity (the volume of space within soil for air or water) or, conversely, its compaction. Porosity in turn affects the extent to which water can infiltrate and permeate the soil. Thus, physical properties influence the amount of water held within soil pores and a soil’s vulnerability to erosion. Of particular interest in terms of agriculture, soil physical properties affect the ease with which plant roots can grow and access soil water and the ease with which seedlings can emerge. Soil temperature also influences plant growth and soil respiration, that is, the release of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the soil.

Every soil has a pH, that is, a degree of acidity, alkalinity, or neutrality. The soil pH affects the amount and availability of plant nutrients, the solubility and motility of heavy metals, microbial growth and diversity, and the soil’s cation exchange capacity (CEC) (Brady 1984). CEC involves the smallest soil particles, colloids, which are formed from weathering and subsequent chemical processes. Colloids can be organic or inorganic and contain a mix of positively or negatively charged exchange sites that can attract negatively or positively charged particles, respectively. Generally, agricultural soils have an overall negative charge that allows them to mostly attract and hold on to positively charged particles, or cations, and mostly repel negatively charged ones, or anions. The degree to which a soil can attract and hold cations is its CEC, while a soil’s ability to attract and hold anions is its anion exchange capacity. Both are regulated by soil properties such as clay content and clay type, soil organic matter levels, and soil pH. Particles that are repelled into the soil solution are available for plant roots and microbes to access and readily take up. CEC and other soil properties such as mineral nutrients, organic matter content, and soil extracellular enzyme activities can offer insights into the biochemical properties of soil.

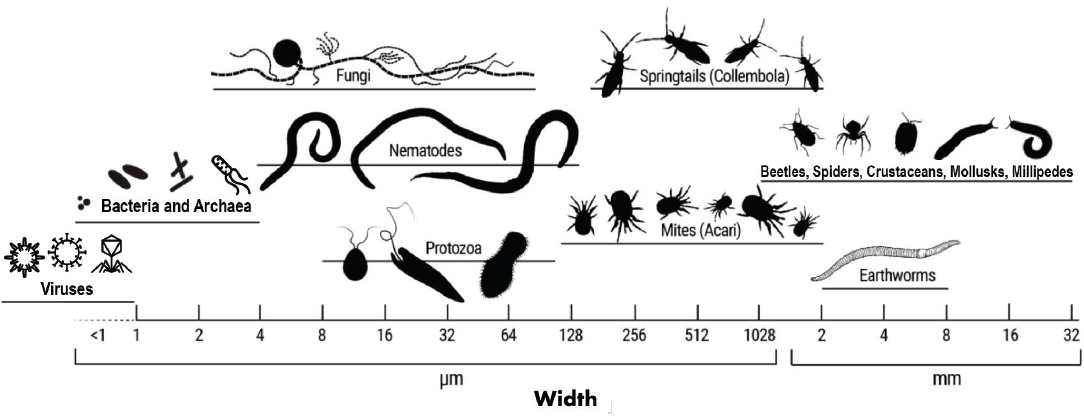

The biological properties of soil consist of the life found within it. Soil is one of the largest reservoirs of biodiversity on Earth and home to 59 ± 15 percent of all species (Fierer 2017; Anthony et al. 2023). Mammals, plants, and millions of much smaller organisms found in soil (Figure 2-3) all contribute to the biological properties.

Biological processes are responsible for most of the functions that are integral to soil health. Soil megafauna and macrofauna—for example, moles, earthworms, and arthropods—burrow through soil, creating pore space and decomposing and redistributing organic matter through bioturbation (Menta 2012). The cutaneous mucous of earthworms and mollusks adds stability and structure to soil (Menta 2012). Soil arthropods regulate biological populations, nutrient cycling, and decomposition (Setälä and McLean 2004). Certain soil arthropods and nematodes (a phylum of roundworms) prey on microbial populations and affect processes such as biogeochemical engineering (Bongers and Bongers 1998; Setälä and McLean 2004).

Plants, with approximately half their biomass belowground, also influence soil biodiversity and soil health by exuding carbon compounds for soil biota in the rhizosphere (Steinauer et al. 2016), providing litter for decomposers, and acting as hosts for symbionts, such as mycorrhizal fungi and rhizobia (Bartelt-Ryser et al. 2005).

NOTE: CEC=cation exchange capacity.

SOURCE: Adapted from Magdoff and van Es (2021).

Because different plant species often occupy unique niches and perform different functions, more diverse plant communities have been associated with higher nutrient uptake, soil carbon storage, and ecosystem resilience (Lange et al. 2015). In addition, plants offer a range of habitats to microorganisms in and above the soil. The complex interactions between plants and soil physical, chemical, and biological properties thus shape the soil habitat and biota in a way that affects subsequent plant growth cycles, which is known as plant–soil feedback.

Microorganisms living in the soil—bacteria, archaea, protists, and fungi—punch above their weight in terms of their size in relationship to the role they play in soil processes.1 Along with driving biogeochemical cycles, bacteria control soil redox, decompose organic matter, and help in disease suppression (Fierer et al. 2012). Knowl-

___________________

1 The committee considered soil microorganisms to consist of living microorganisms in the soil, per discussion found in Berg et al. (2020). Further discussion of this term in relation to the microbiome is found below in the section “Microbiomes and One Health.”

edge of the presence and diversity of archaea in soil has recently expanded with discovery of archaea engaged in nitrogen fixation, phosphorus solubilization, siderophore production, sulfur cycling, nitrification, and other processes in soil (Naitam and Kaushik 2021). Fungi, including mycorrhizal fungi, decomposers, and many other groups, are important for nutrient cycling (Veresoglou et al. 2012), causing and preventing plant disease, improving plant drought tolerance, and contributing to soil structure formation (Delavaux et al. 2017; Bahram et al. 2018). Protists (which include several groups of protozoa, unicellular algae, and fungi) participate in decomposition, nutrient cycling, soil structure formation, pest and disease control, and many other processes (Geisen et al. 2016). Additionally, the potential role of viruses in soils is just starting to be appreciated. Emerging evidence suggests that these obligate parasites can sustain soil biodiversity and influence a range of processes including nutrient cycling, carbon dynamics, and plant health (Liang et al. 2024).

Few species of soil biota act alone; instead, most are intimately interconnected in complex food webs. Their interactions—including predation and parasitism, cooperation and symbiosis, and competition (Scheu 2002; Thakur and Geisen 2019)—affect nutrient cycling, plant health, and overall ecosystem functioning.

Soil organisms’ distribution and access to nutrients is very much shaped by their physical environment, for example, aggregation and pore size (Erktan et al. 2020; Hartmann and Six 2023), and by soil pH (Crowther et al. 2019). Soil organisms, in turn, help construct their habitat by binding soil particles with extracellular polymeric substances and hyphae into stable aggregates (Rillig and Mummey 2006), creating pores and channels (Lavelle et al. 2016), and providing microenvironments for building soil organic matter (Figure 2-4; Six et al. 2004). Thus, all the properties of soil work together to complete the picture of soil health.

Soil health is not uniform. Because the physical, chemical, and biological properties of soil vary by geography, topography, and parent material, all soils can meet the definition of soil health to sustain productivity, diversity, and environmental services even if they are extremely different in composition from one to the next. Whether a soil meets the definition of soil health depends, in large part, on human activities at the local scale (e.g., management practices in agricultural systems, Chapter 4) and at the global scale (e.g., climate change, Box 2-2).

HUMAN HEALTH AND WELLNESS

The One Health concept posits that as the health of one system or organism suffers, the health of humans is also adversely affected. How the state of soil health affects human health is the question of interest in this report. However, as with soil, health and wellness in humans have many facets.

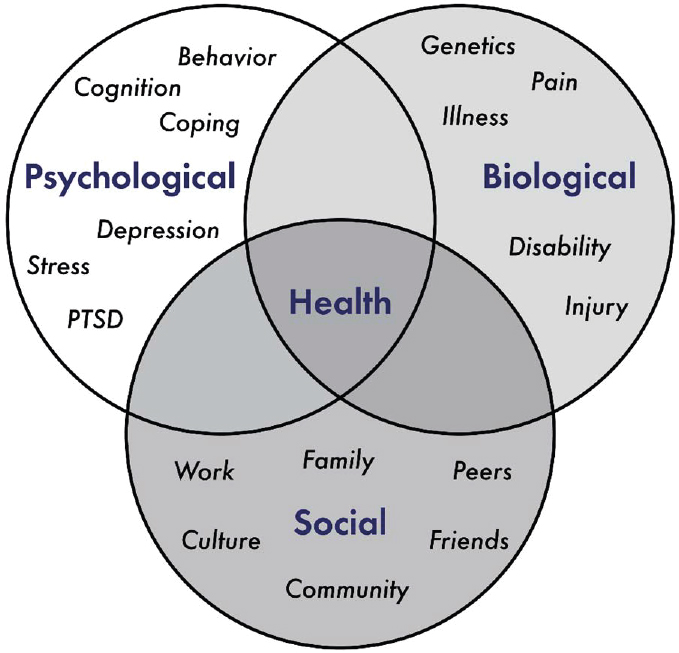

In 1948, WHO amended its constitution to define health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO 1992). This definition was groundbreaking at the time because it shifted the emphasis to a positive state of well-being that included physical, mental, and social domains (Figure 2-5). Although it is still in use today, this definition of health has been criticized because it is difficult to delineate and maintain a “complete” state of

NOTES: Green=various microbial processes. Yellow=soil chemical properties. Orange=physical properties. The color of the arrow indicates the affected soil properties. EPS=extracellular polymeric substance. MICP=microbially induced carbonate precipitation.

SOURCE: Used with permission of Springer Nature BV, from “The Interplay Between Microbial Communities and Soil Properties”, Philippot et al., Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2023; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

BOX 2-2

Climate Change and Soil Health

Climate affects the multiple and coupled physical, chemical, and biological processes involved in soil health through changes in atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2), temperature, and precipitation patterns (FAO 2015; Talukder et al. 2021). Higher CO2 levels enhance plant photosynthesis and carbohydrate production, leading to increased carbon deposition in the root zone, which in turn affects the biological processes that govern the soil carbon cycle (Preece and Peñuelas 2016; Toreti et al. 2020; Sun et al. 2021; Usyskin-Tonne et al. 2021). Consequences of these shifts include alterations in coupled biogeochemical cycles such as increases in rates of nitrogen mineralization and cycling (Wardle et al. 2004; Horwath and Kuzyakov 2018). Climate change is significantly intensifying the frequency and severity of droughts in soils, with rising global temperatures contributing to increased evaporation rates, decreased soil moisture, and altered precipitation patterns (Trenberth 2011). Extreme floods and droughts cause significant soil erosion and degradation, affecting the soil’s ability to store carbon and support plant growth (FAO 2015), and more generally, agricultural productivity and ecosystem health (Dai 2011; Cook et al. 2014). While droughts reduce soil moisture, affecting plant growth and soil microbial activity, excessive rainfall can result in soil erosion and nutrient leaching and degrade soil structure (Doran and Zeiss 2000; Lal 2020). Changes in weather patterns vary regionally, with some areas facing more intense and prolonged droughts, and others experiencing increased precipitation (Sheffield and Wood 2011), thus highlighting the complexity of climate change impacts on soil health.

Shifts in atmospheric CO2 levels, temperature, and precipitation patterns caused by climate change also affect the soil microbiome (Rillig et al. 2019; Zhou et al. 2020). Elevated CO2 can enhance plant growth, thus increasing and/ or changing root exudates and plant residues, which in turn influence microbial diversity and function (Cavicchioli et al. 2019). Temperature shifts directly affect rates of microbial metabolism; warmer temperatures typically accelerate microbial activity, decomposition, and potentially greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Classen et al. 2015; Jansson and Hofmockel 2020). Furthermore, precipitation determines soil moisture, crucial for microbial survival and activity (Classen et al. 2015). Changes in soil water—such as saturation during flooding or desiccation during droughts—profoundly shift microbial community structure and nutrient cycling dynamics, with cascading effects on carbon storage, GHG emissions, and soil food webs. Climate change−induced alterations in the soil microbiome directly translate into changes to soil health, nutrient availability, and overall ecosystem functioning, underscoring the importance of understanding these interactions in the context of global climate change (Cavicchioli et al. 2019; Jansson and Hofmockel 2020).

SOURCE: Bolton et al. (2018). Reprinted by Permission of SAGE Publications.

well-being (Huber et al. 2011). For example, with technology, thresholds for disease diagnosis and intervention have changed, making it easier to identify earlier stages of disease that may not have previously been identifiable or impactful. Moreover, patterns in the global burden of disease have shifted from acute infectious conditions to higher rates of noncommunicable chronic illnesses.

Some groups have therefore advocated for a shift toward a conceptual framework of health that emphasizes social and personal resources in addition to physical capacity that enables individuals to adapt and self-manage. The Ottawa Charter, an international agreement signed at the First International Conference on Health Promotion organized by WHO in 1986, states that health is “a resource for everyday life, not the objective of living” (WHO 1986). In this conceptualization, health promotion moves beyond the health sector to include fundamental conditions and resources for health—that is, peace, shelter, education, food, income, a stable ecosystem, sustainable resources, social justice, and equity. It is notable that multiple One Health objectives related to soil health, including food (see further discussion in Box 2-3), a stable ecosystem, and sustainable resources, are among the fundamental conditions and resources for health defined by the WHO Ottawa Charter.

BOX 2-3

Food as a Prerequisite for Health

Food is one of WHO’s prerequisites for health. Presumably, the charter authors intended food as a resource for health to be safe, available, affordable, and nutritious. Food security is a state of adequate and consistent access to foods that sustain health and well-being (Coleman-Jensen et al. 2021). While food quantity is a primary component of food security, other dimensions including nutritional quality, food safety, and suitability to dietary preferences are equally important. Further, a state of food security ensures that foods are accessed in socially acceptable ways, free from psychological burden. The dimensions of availability, access, and utilization are recognized.

Food security is deeply intertwined with nutrition access. Usher (2015) developed a framework for this concept that includes acceptability, accessibility, accommodation, affordability, and availability as dimensions of access. This model postulates that true access to healthy foods should account for acceptable interactions between consumers and retailers (acceptability); healthy foods being accessible in terms of location, mode of transportation, and distance (accessibility); compatible hours during which healthy foods can be purchased (accommodation); pricing that is compatible with household income level and food assistance resources (affordability); and healthy foods being available in sufficient quantity and variety (availability). It is important to account for potential discrepancies between observed metrics of nutrition access, such as food retailer density, and perceived nutrition access.

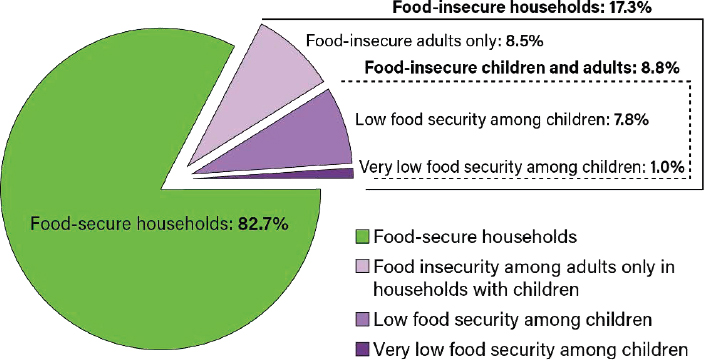

Food and nutrition insecurity lead to increases in infectious and cardiometabolic disease risk among adults (Seligman and Schillinger 2010; Seligman et al. 2010; Berkowitz et al. 2014; Seligman and Berkowitz 2019; Myers et al. 2020). The long-term health impacts of food insecurity in childhood later in life are not yet fully understood (Te Vazquez et al. 2021). In 2022, the prevalence of U.S. households with food insecurity (combining low and very low food security) was 17.3 percent (44.2 million people, including 7.3 million children) (Figure 2-6). This burden is not experienced equally across the whole population. Whereas poverty is the primary underlying cause of food insecurity (Laraia et al. 2017), other household and individual characteristics are strongly associated. The risk for food insecurity is higher among households with children and with women as the primary income earner, older adults, racial/ethnic minorities, Southern states, rural areas and inner cities, and individuals with mental disabilities.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Agriculture–Economic Research Service. “Food Security in the U.S., Key Statistics & Graphics.” Accessed April 29, 2024. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/key-statistics-graphics/.

Health Equity

The WHO constitution states that “the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.” Health equity means that everyone has an opportunity to be as healthy as possible. To achieve this, health disparities must be identified and addressed. A health disparity or inequity has been defined as a particular type of difference in health in which disadvantaged social groups—such as those living in poverty, racial or ethnic minorities, women, or other groups who have persistently experienced social disadvantage or discrimination—systematically experience worse health or greater health risks than more advantaged social groups (Braveman 2006). Measurement of health disparities therefore requires an indicator or modifiable determinant of health, an indicator of social position or way of categorizing people into different groups, and a method for comparing the health or health determinant indicator across groups.

Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health are the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes across the lifespan (Figure 2-7). They include the physical environment (see Box 2-4) but also the economic policies and systems, social norms, social policies, and political systems that shape daily life. Social determinants of health can be even more important than health care in ensuring a healthy population and contribute to a relatively large proportion of inequities in health (Bunker et al. 1994). There is often a tendency to focus on how individual behaviors, such as diet, smoking, and alcohol, lead to health inequities and ignore the upstream drivers of these behaviors—the causes of the causes. Healthy People 2030 groups social determinants of health into five domains: economic stability (which includes a focus on food security and healthy eating), education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and the social and community context (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services n.d.).

MICROBIOMES AND ONE HEALTH

As with soil, microorganisms are not explicitly identified in the definition of One Health. A growing recognition of their importance to the health of ecosystems and organisms and the connective role they play between organisms and between organisms and ecosystems has led to calls for greater visibility within the concept of One Health (Trinh et al. 2018; van Bruggen et al. 2019; Berg et al. 2020; Singh et al. 2023).

Microbiome

Microorganisms interact with each other to form communities, which occupy habitats with “distinct physico-chemical properties” (Whipps et al. 1988). However, microorganisms are not alone in these habitats. Along with the structure and conditions of the environment, microorganisms also affect and are affected by viruses, relic DNA, and metabolites. For example, soil viruses, both those targeting eukaryotic and single-celled microorganisms, are increasingly appreciated for their capacities to alter composition and functioning (Emerson et al. 2018; Albright et al. 2022; Jansson and Wu 2023). Therefore, microorganisms live in a microbiome, which consists of the microbial community, the environment, and microbial structural elements and metabolites with which they interact (Whipps et al. 1988; Berg et al. 2020).

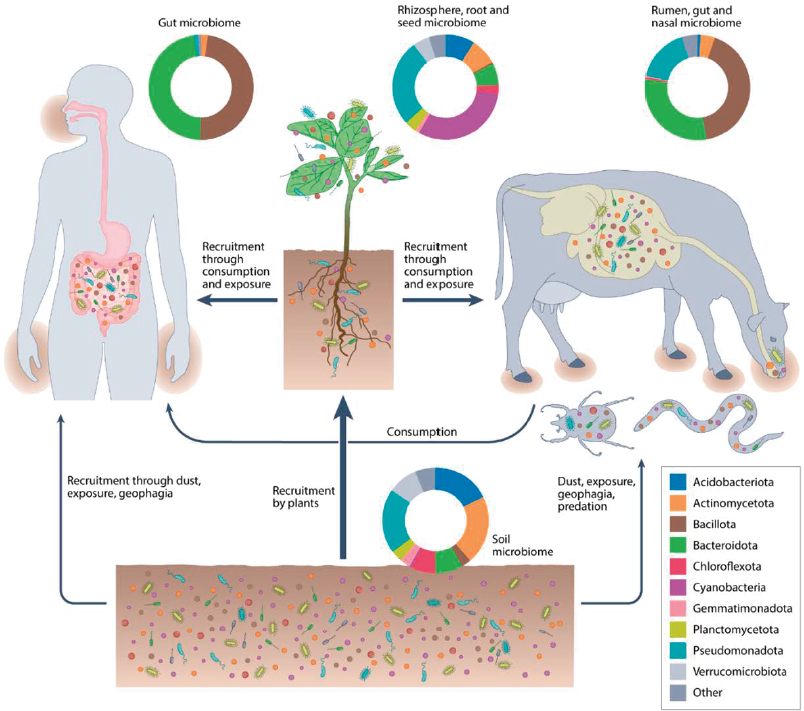

In addition to existing in a particular environment, studies in recent years suggested that different microbiomes are perhaps interconnected and form a circular loop (Figure 2-8; Singh et al. 2020; Banerjee and van der Heijden 2023; Sessitsch et al. 2023). Microbiomes exist in all eukaryotic organisms and in diverse ecosystems; the committee focused on the microbiomes and connectivity thereof for soil, plants, and humans, as per its charge.

SOURCE: Healthy People 2030, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Accessed November 8, 2023. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health.

Soil and Plant Microbiomes

Just as soil health does not look the same across soils, there is not one soil microbiome or a soil microbiome archetype (Fierer 2017). Spatial variability can create enough difference in the environment that two samples taken within a foot of each other have different microbiomes (Fierer 2017; Berg et al. 2020). It is estimated that there are, at a minimum, 6 million microbial species that live in soil (Anthony et al. 2023), an estimate that does even not include viruses. As is discussed in Chapter 3, these microorganisms are the workhorses of the biogeochemical cycles on Earth. It is likely that each step in a cycle is carried out by diverse soil taxa working together and that many taxa perform redundant functions. However, precisely which microorganisms do what, with which other microorganisms, and under what conditions is not yet known (Fierer 2017; Singh et al. 2023). What is known is that this abundant diversity in soil microbiomes is critical to optimal function (Singh et al. 2014; Wagg et al. 2021).

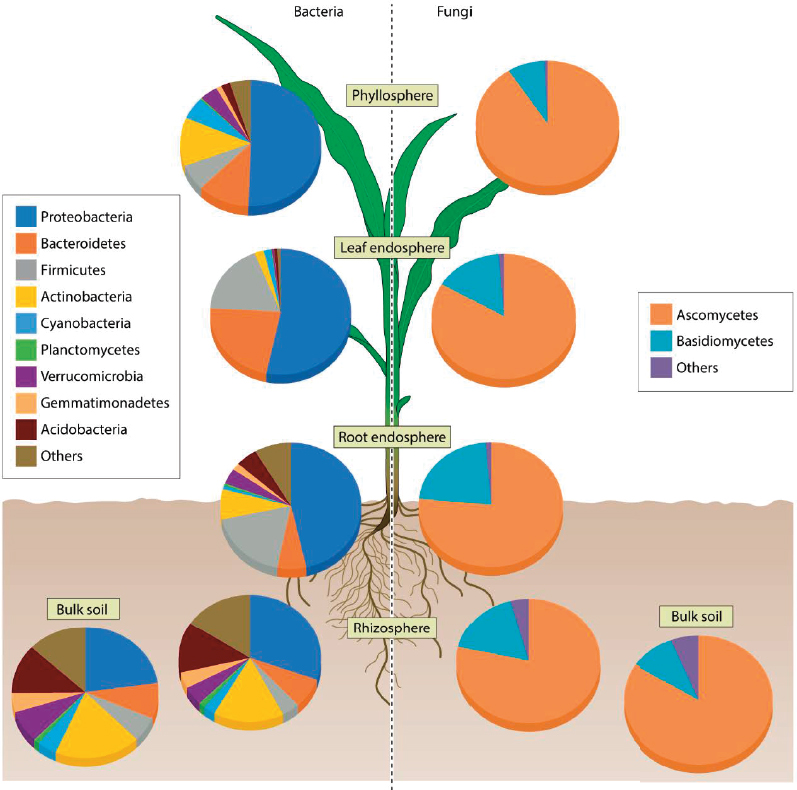

This diversity is also critical because soil supplies much of the microbiota to other organisms, including plants (Figure 2-9; van Bruggen et al. 2019; Banerjee and van der Heijden 2023). Plants have their own microbiomes, including the rhizosphere, the root endosphere, and the phyllosphere (van Bruggen et al. 2019; Trivedi et al. 2020). Each

BOX 2-4

Influence of the Environment on Human Health

Environmental health is the branch of public health focused on how the built and the natural environment influence human health. There are many indirect and direct ways in which the environment can influence human health (Barton and Grant 2006). Together, environmental influences can have a large impact on health. Large studies have attributed 15−23 percent of global deaths and 12−22 percent of global morbidity (measured as disability adjusted life years [DALYs]) to environmental risks (Global Burden of Disease Risk Factors Collaborators et al. 2015; Prüss-Ustün et al. 2017).

Most of the research on environmental factors and health has focused on the impacts of pollutants and chemicals, especially in the air and water. Federal laws in the United States, such as the Clean Air Act and Safe Drinking Water Act, that regulate air and water quality have helped to reduce the harmful health effects of pollutants (Weinmeyer et al. 2017; Nethery et al. 2020), but continued reduction of exposures remains a priority. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Service’s Healthy People 2030 initiative specifically lists reduction of exposure to harmful pollutants in soil, in addition to air, water, and materials in homes and workplaces, as a key objective (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services n.d.).

There are also data on the health benefits of the natural environment. Living in or near to greener and more biodiverse environments reduces mortality rates and improves mental well-being (Bowler et al. 2010; Haahtela 2019). Some of the effect appears to be related to increased activity levels and social cohesion, and exposure to soil microbes is also likely to play a role (Rook 2013). Microbes in soil, dust, and on foods impact immune system development, function, and even human behavior. For example, early exposure to microbes is likely to promote allergen tolerance (Rook 2013; Ottman et al. 2019).

sphere is home to a unique microbiome (Edwards et al. 2015; Trivedi et al. 2020; Figure 2-10). For example, the rhizosphere microbiome—the narrow zone of soil close to plant roots and influenced by root exudates—modulates immunity and nutrient acquisition. Rhizosphere communities and soil mutualists (e.g., mycorrhizal fungi) are in part responsible for a plant’s tolerance to drought, salinity, nutrient deficiencies, pathogens, and high temperatures (Delavaux et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2018).

Plant roots also harbor a diverse microbiota, including mycorrhizal fungi (fungi that live on or in plant roots) and rhizobia (nitrogen-fixing bacteria that live in legume root nodules). The root endosphere, that is, the microorganisms living within the plant roots, are recruited to the plant from the rhizosphere (Bulgarelli et al. 2015). The response of plant metabolism to stress changes the composition of the microbial community that is recruited (Pepper and Brooks 2021).

SOURCE: Adaptation used with permission of American Society of Microbiology–Journals, from “Microbiome Interconnectedness throughout Environments and with Major Consequences for Healthy People and a Healthy Planet”, Sessitsch et al., Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 87 (3), 2023; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

SOURCE: Used with permission of Springer Nature BV, from “Soil Microbiomes and One Health”, Banerjee and van der Heijden, Nature Reviews Microbiology 21 (1), 2023; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

The phyllosphere microbiome is found on leaf and stem surfaces. Despite the oligotrophic environment and harsh environmental factors such as high temperature, precipitation, and solar radiation, a thriving microbial community can be seen in the phyllosphere (Vorholt 2012). Studies have found that soil microbial communities are even a source of microbiota to this aboveground microbiome (Trivedi et al. 2020). Thus, soil microbial communities play a critical role in shaping the structure, composition, and functioning of plant-associated microbiota (Fierer 2017).

Human Microbiomes

Similar to plants, animals evolved symbiotic microorganisms, with different body parts comprising distinct assemblages of microbiota (Ley et al. 2008). Compared to

SOURCE: Used with permission of Springer Nature BV, from “Plant–Microbiome Interactions: From Community Assembly to Plant Health”, Trivedi et al., Nature Reviews Microbiology 18 (11), 2020; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

about 23,000 genes in the human genome, the number of microbial genes can be over 3 million, producing thousands of metabolites that shape human immunity, nutrition, growth, and health (Gilbert et al. 2018; Valdes et al. 2018). For example, as many as 100 trillion microorganisms reside in the human gastrointestinal tract (Lozupone et al. 2012). Gut microbes are known to confer fermentation capacities of nondigestible substrates such as dietary fibers and endogenous intestinal mucus, facilitating microbes able to produce short-chain fatty acids and gases. The gut microbiota also influences human health through modulating immune, metabolic, and behavioral traits (Valdes et al. 2018). The oral microbiome is also incredibly diverse and is the second largest micro-

bial community in the human body (Deo and Deshmukh 2019). Remarkably, each part of the human tongue has its distinct microbial community (Wilbert et al. 2020). Other human body parts, such as skin, nostrils, and genital organs, also comprise consistently abundant microbial communities.

Microbiomes as a Conduit Between Soil Health and Human Health

Making direct connections between soil health and human health can be challenging. Although similar characteristics can be measured in humans and soils, they also provide evidence of the difficulty in defining healthy soils as well as healthy humans, due to the lack of standards, detectable biomarkers, and comparable metrics in some cases (Table 2-1). One opportunity for solving this challenge is identifying connectivity between microbiomes; however, establishment of microbes in humans from soil and plant microbiomes is still underexplored. Although there seems to be little overlap between the microbiomes of soils and humans, there are compositional and functional similarities between the plant rhizosphere and the human gut microbiome (Blum et al. 2019). As discussed previously and in greater detail in Chapters 4 and 5, soil microorganisms heavily influence plants. How the relationship of soil microbiomes to plant microbiomes may in turn affect human microbiomes is less evident. This ambiguity includes the degree to which agricultural management practices have an effect on the nutrient density of foods.

As the One Health approach is predicated on interdependence, there could perhaps be no more obvious integrator across the health of all organisms than the soil microbiome. The activity (or lack thereof) that occurs within soil microbiomes—for example, nutrient cycling, soil structure, and carbon sequestration—has profound implications for the health of ecosystems and people, including the needs prioritized in the definition of One Health (i.e., healthy food, water, and air and action on climate change; Chapter 3). The ability of microorganisms to suppress plant disease or sorb or breakdown contami-

TABLE 2-1 Examples of Measurable Characteristics of Healthy Soils and Healthy Humans

| Soil | Human | |

| Biochemical compositional analysis | Nutrient composition (carbon, nitrogen, phosphorous, potassium), contaminants | Blood tests measuring metabolism, homeostasis, organ function, cell counts |

| Physical characteristics that can be measured | Depth of topsoil, physical structure of soil | Body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, autonomic tone, body weight, reflexes |

| Functional measures of systems and their performance | Water-holding capacity, mutualistic and pathogenic organisms, bioaccessibility of nutrients in soil | Mobility, disease, frailty/vigor, cognitive performance, physical strength/performance, cardiorespiratory fitness |

| Other | Microbiome composition including prospective pharmaceuticals | Microbiome, subjective well-being, pain |

nants affects the environmental hazards and soil-borne pathogens to which people may be exposed (Chapters 3–6), and the One Health Joint Plan of Action specifically recognizes pollution and waste management as an area in need of more attention (Chapters 4 and 6). Even though there is much more to learn about the connection between soil health and human health, there is mounting evidence that exposure to environmental microorganisms can have positive impacts on human health, as discussed in Chapter 7. Clearly, greater attention to the activity and health of soil microbiomes would be pragmatic in the pursuit of One Health.

REFERENCES

Albright, Michaeline B. N., La Verne Gallegos-Graves, Kelli L. Feeser, Kyana Montoya, Joanne B. Emerson, Migun Shakya, and John Dunbar. 2022. “Experimental Evidence for the Impact of Soil Viruses on Carbon Cycling During Surface Plant Litter Decomposition.” ISME Communications 2 (1): 24. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43705-022-00109-4.

Anthony, Mark A., S. Franz Bender, and Marcel G. A. van der Heijden. 2023. “Enumerating Soil Biodiversity.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120 (33): e2304663120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2304663120.

Bahram, Mohammad, Falk Hildebrand, Sofia K. Forslund, Jennifer L. Anderson, Nadejda A. Soudzilovskaia, Peter M. Bodegom, Johan Bengtsson-Palme, Sten Anslan, Luis Pedro Coelho, Helery Harend, Jaime Huerta-Cepas, Marnix H. Medema, Mia R. Maltz, Sunil Mundra, Pål Axel Olsson, Mari Pent, Sergei Põlme, Shinichi Sunagawa, Martin Ryberg, Leho Tedersoo, and Peer Bork. 2018. “Structure and Function of the Global Topsoil Microbiome.” Nature 560 (7717): 233−237. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0386-6.

Banerjee, Samiran, and Marcel G. A. van der Heijden. 2023. “Soil Microbiomes and One Health.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 21 (1): 6−20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-022-00779-w.

Barrett, Meredith A., and Timothy A. Bouley. 2015. “Need for Enhanced Environmental Representation in the Implementation of One Health.” EcoHealth 12 (2): 212−219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-014-0964-5.

Bartelt-Ryser, Janine, Jasmin Joshi, Bernhard Schmid, Helmut Brandl, and Teri Balser. 2005. “Soil Feedbacks of Plant Diversity on Soil Microbial Communities and Subsequent Plant Growth.” Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 7 (1): 27−49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppees.2004.11.002.

Barton, Hugh, and Marcus Grant. 2006. “A Health Map for the Local Human Habitat.” Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health 126 (6): 252−253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466424006070466.

Berg, Gabriele, Daria Rybakova, Doreen Fischer, Tomislav Cernava, Marie-Christine Champomier Vergès, Trevor Charles, Xiaoyulong Chen, Luca Cocolin, Kellye Eversole, Gema Herrero Corral, Maria Kazou, Linda Kinkel, Lene Lange, Nelson Lima, Alexander Loy, James A. Macklin, Emmanuelle Maguin, Tim Mauchline, Ryan McClure, Birgit Mitter, Matthew Ryan, Inga Sarand, Hauke Smidt, Bettina Schelkle, Hugo Roume, G. Seghal Kiran, Joseph Selvin, Rafael Soares Correa de Souza, Leo van Overbeek, Brajesh K. Singh, Michael Wagner, Aaron Walsh, Angela Sessitsch, and Michael Schloter. 2020. “Microbiome Definition Re-visited: Old Concepts and New Challenges.” Microbiome 8 (1): 103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-020-00875-0.

Berkowitz, Seth A., Hilary K. Seligman, and Niteesh K. Choudhry. 2014. “Treat or Eat: Food Insecurity, Cost-related Medication Underuse, and Unmet Needs.” The American Journal of Medicine 127 (4): 303-310.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.01.002.

Bigelow, Daniel P., and Allison Borchers. 2017. Major Uses of Land in the United States, 2012. EIB-178, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

Blum, Winfried E. H., Sophie Zechmeister-Boltenstern, and Katharina M. Keiblinger. 2019. “Does Soil Contribute to the Human Gut Microbiome?” Microorganisms 7 (9): 287. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fmicroorganisms7090287.

Bolton, Rendelle E., Gemmae M. Fix, Carol VanDeusen Lukas, A. Rani Elwy, and Barbara G. Bokhour. 2018. “Biopsychosocial Benefits of Movement-based Complementary and Integrative Health Therapies for Patients with Chronic Conditions.” Chronic Illness 16 (1): 41−54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395318782377.

Bongers, Tom, and Marina Bongers. 1998. “Functional Diversity of Nematodes.” Applied Soil Ecology 10 (3): 239−251. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-1393(98)00123-1.

Borrelli, Pasquale, David A. Robinson, Larissa R. Fleischer, Emanuele Lugato, Cristiano Ballabio, Christine Alewell, Katrin Meusburger, Sirio Modugno, Brigitta Schütt, Vito Ferro, Vincenzo Bagarello, Kristof Van Oost, Luca Montanarella, and Panos Panagos. 2017. “An Assessment of the Global Impact of 21st Century Land Use Change on Soil Erosion.” Nature Communications 8 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02142-7.

Bowler, Diana E., Lisette M. Buyung-Ali, Teri M. Knight, and Andrew S. Pullin. 2010. “A Systematic Review of Evidence for the Added Benefits to Health of Exposure to Natural Environments.” BMC Public Health 10 (1): 456. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-456.

Brackin, Richard, Susanne Schmidt, David Walter, Shamsul Bhuiyan, Scott Buckley, and Jay Anderson. 2017. “Soil Biological Health—What Is It and How Can We Improve It?” International Sugar Journal 119 (1426): 806−814.

Brady, Nyle C. 1984. The Nature and Properties of Soils. 9th edition. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Braveman, Paula. 2006. “Health Disparities and Health Equity: Concepts and Measurement.” Annual Review of Public Health 27 (1): 167−194. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102103.

Bulgarelli, Davide, Ruben Garrido-Oter, Philipp C. Münch, Aaron Weiman, Johannes Dröge, Yao Pan, Alice C. McHardy, and Paul Schulze-Lefert. 2015. “Structure and Function of the Bacterial Root Microbiota in Wild and Domesticated Barley.” Cell Host & Microbe 17 (3): 392−403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2015.01.011.

Bünemann, Else K., Giulia Bongiorno, Zhanguo Bai, Rachel E. Creamer, Gerlinde De Deyn, Ron de Goede, Luuk Fleskens, Violette Geissen, Thom W. Kuyper, Paul Mäder, Mirjam Pulleman, Wijnand Sukkel, Jan Willem van Groenigen, and Lijbert Brussaard. 2018. “Soil Quality—A Critical Review.” Soil Biology and Biochemistry 120: 105−125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.01.030.

Bunker, John P., Howard S. Frazier, and Frederick Mosteller. 1994. “Improving Health: Measuring Effects of Medical Care.” The Milbank Quarterly 72 (2): 225−258. https://doi.org/10.2307/3350295.

Cavicchioli, Ricardo, William J. Ripple, Kenneth N. Timmis, Farooq Azam, Lars R. Bakken, Matthew Baylis, Michael J. Behrenfeld, Antje Boetius, Philip W. Boyd, Aimée T. Classen, Thomas W. Crowther, Roberto Danovaro, Christine M. Foreman, Jef Huisman, David A. Hutchins, Janet K. Jansson, David M. Karl, Britt Koskella, David B. Mark Welch, Jennifer B. H. Martiny, Mary Ann Moran, Victoria J. Orphan, David S. Reay, Justin V. Remais, Virginia I. Rich, Brajesh K. Singh, Lisa Y. Stein, Frank J. Stewart, Matthew B. Sullivan, Madeleine J. H. van Oppen, Scott C. Weaver, Eric A. Webb, and Nicole S. Webster. 2019. “Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: Microorganisms and Climate Change.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 17 (9): 569−586. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-019-0222-5.

Classen, Aimée T., Maja K. Sundqvist, Jeremiah A. Henning, Gregory S. Newman, Jessica A. M. Moore, Melissa A. Cregger, Leigh C. Moorhead, and Courtney M. Patterson. 2015. “Direct and Indirect Effects of Climate Change on Soil Microbial and Soil Microbial-Plant Interactions: What Lies Ahead?” Ecosphere 6 (8): art130. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES15-00217.1.

Coleman-Jensen, Alicia, Matthew P. Rabbitt, Christian A. Gregory, and Anita Singh. 2021. Household Food Security in the United States in 2020, ERR-298. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

Cook, Benjamin I., Jason E. Smerdon, Richard Seager, and Sloan Coats. 2014. “Global Warming and 21st Century Drying.” Climate Dynamics 43 (9): 2607−2627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-014-2075-y.

Cook, Robert A., William B. Karesh, and Steven A. Osofsky. 2004. “The Manhattan Principles on ‘One World, One Health’.” One World, One Health: Building Interdisciplinary Bridges to Health in a Globalized World. Wildlife Conservation Society. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://oneworldonehealth.wcs.org/About-Us/Mission/The-Manhattan-Principles.aspx.

Crowther, T. W., J. van den Hoogen, J. Wan, M. A. Mayes, A. D. Keiser, L. Mo, C. Averill, and D. S. Maynard. 2019. “The Global Soil Community and Its Influence on Biogeochemistry.” Science 365 (6455): eeav0550. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aav0550.

Dahl, Thomas E. 1990. Wetland Losses in the United States 1780s to 1980s. Report to Congress. U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Wetlands-Losses-in-the-United-States-1780sto-1980s.pdf.

Dai, Aiguo. 2011. “Drought Under Global Warming: A Review.” WIREs Climate Change 2 (1): 45−65. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.81.

De Kimpe, Christian R., and Jean-Louis Morel. 2000. “Urban Soil Management: A Growing Concern.” Soil Science 165 (1): 31−40.

Delavaux, Camille S., Lauren M. Smith-Ramesh, and Sara E. Kuebbing. 2017. “Beyond Nutrients: A Meta-analysis of the Diverse Effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Plants and Soils.” Ecology 98 (8): 2111−2119. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.1892.

Deo, Priya, and Revati Deshmukh. 2019. “Oral Microbiome: Unveiling the Fundamentals.” Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology 23: 122−128. https://doi.org/10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_304_18.

Doran, John W., and Michael R. Zeiss. 2000. “Soil Health and Sustainability: Managing the Biotic Component of Soil Quality.” Applied Soil Ecology 15 (1): 3−11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-1393(00)00067-6.

Edwards, Joseph, Cameron Johnson, Christian Santos-Medellín, Eugene Lurie, Natraj Kumar Podishetty, Srijak Bhatnagar, Jonathan A. Eisen, and Venkatesan Sundaresan. 2015. “Structure, Variation, and Assembly of the Root-Associated Microbiomes of Rice.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (8): E911−E920. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1414592112.

Ellis, Erle, Kees Klein Goldewijk, Stefan Siebert, Deb Lightman, and Navin Ramankutty. 2010. “Anthropogenic Transformation of the Biomes, 1700 to 2000.” Global Ecology and Biogeography 19: 589−606. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00540.x.

Emerson, Joanne B., Simon Roux, Jennifer R. Brum, Benjamin Bolduc, Ben J. Woodcroft, Ho Bin Jang, Caitlin M. Singleton, Lindsey M. Solden, Adrian E. Naas, Joel A. Boyd, Suzanne B. Hodgkins, Rachel M. Wilson, Gareth Trubl, Changsheng Li, Steve Frolking, Phillip B. Pope, Kelly C. Wrighton, Patrick M. Crill, Jeffrey P. Chanton, Scott R. Saleska, Gene W. Tyson, Virginia I. Rich, and Matthew B. Sullivan. 2018. “Host-Linked Soil Viral Ecology Along a Permafrost Thaw Gradient.” Nature Microbiology 3 (8): 870−880. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0190-y.

Erktan, Amandine, Dani Or, and Stefan Scheu. 2020. “The Physical Structure of Soil: Determinant and Consequence of Trophic Interactions.” Soil Biology and Biochemistry 148: 107876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2020.107876.

Evans, B. R., and Frederick Leighton. 2014. “A History of One Health.” Revue Scientifique et Technique (International Office of Epizootics) 33: 413−420. https://doi.org/10.20506/rst.33.2.2298.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). 2015. The Status of the World’s Soil Resources (Main Report). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/3/i5199e/I5199E.pdf.

FAO. 2020. “Towards a Definition of Soil Health.” Intergovernmental Technical Panel on Soils. FAO. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://www.fao.org/3/cb1110en/cb1110en.pdf.

FAO, OIE, and WHO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Office of International des Epizooties, and World Health Organization). 2010. “The FAO-OIE-WHO Collaboration. Sharing Responsibilities and Coordinating Global Activities to Address Health Risks at the Animal-Human Ecosystems Interfaces.” A Tripartite Concept Note. WHO. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/the-fao-oiewho-collaboration.

FAO, UNEP, WHO, and WOAH (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, United Nations Environment Programme, World Health Organization, and World Organisation for Animal Health). 2022. One Health Joint Plan of Action (2022–2026). Working Together for the Health of Humans, Animals, Plants and the Environment. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc2289en.

Fierer, Noah. 2017. “Embracing the Unknown: Disentangling the Complexities of the Soil Microbiome.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 15 (10): 579−590. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.87.

Fierer, Noah, Jonathan W. Leff, Byron J. Adams, Uffe N. Nielsen, Scott Thomas Bates, Christian L. Lauber, Sarah Owens, Jack A. Gilbert, Diana H. Wall, and J. Gregory Caporaso. 2012. “Cross-Biome Metagenomic Analyses of Soil Microbial Communities and Their Functional Attributes.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (52): 21390−21395. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1215210110.

Geisen, Stefan, Robert Koller, Maike Hünninghaus, Kenneth Dumack, Tim Urich, and Michael Bonkowski. 2016. “The Soil Food Web Revisited: Diverse and Widespread Mycophagous Soil Protists.” Soil Biology and Biochemistry 94: 10−18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.11.010.

Gibbs, E. Paul J. 2014. “The Evolution of One Health: A Decade of Progress and Challenges for the Future.” Vet Record 174 (4): 85−91. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.g143.

Gilbert, Jack A., Martin J. Blaser, J. Gregory Caporaso, Janet K. Jansson, Susan V. Lynch, and Rob Knight. 2018. “Current Understanding of the Human Microbiome.” Nature Medicine 24 (4): 392−400. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4517.

Global Burden of Disease Risk Factors Collaborators, Mohammad H. Forouzanfar, Lily Alexander, H. Ross Anderson, Victoria F. Bachman, Stan Biryukov, Michael Brauer, Richard Burnett, Daniel Casey, Matthew M. Coates, Aaron Cohen, Kristen Delwiche, Kara Estep, Joseph J. Frostad, Astha KC, Hmwe H. Kyu et al. 2015. “Global, Regional, and National Comparative Risk Assessment of 79 Behavioural, Environmental and Occupational, and Metabolic Risks or Clusters of Risks in 188 Countries, 1990–2013: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.” The Lancet 386 (10010): 2287−2323. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00128-2.

Guo, L. B., and Roger M. Gifford. 2002. “Soil Carbon Stocks and Land Use Change: A Meta Analysis.” Global Change Biology 8 (4): 345-360. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.13541013.2002.00486.x.

Haahtela, Tari. 2019. “A Biodiversity Hypothesis.” Allergy 74 (8): 1445−1456. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13763.

Hartmann, Martin, and Johan Six. 2023. “Soil Structure and Microbiome Functions in Agroecosystems.” Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 4: 1−15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-022-00366-w.

Horwath, William, and Yakov Kuzyakov. 2018. “Chapter Three - The Potential for Soils to Mitigate Climate Change Through Carbon Sequestration.” In Climate Change Impacts on Soil Processes and Ecosystem Properties, edited by William R. Horwath and Yakov Kuzyakov, 61−92. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Huber, Machteld, J. André Knottnerus, Lawrence Green, Henriëtte van der Horst, Alejandro R. Jadad, Daan Kromhout, Brian Leonard, Kate Lorig, Maria Isabel Loureiro, Jos W. M. van der Meer, Paul Schnabel, Richard Smith, Chris van Weel, and Henk Smid. 2011. “How Should We Define Health?” BMJ 343: d4163. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4163.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). 2022. “Summary for Policymakers.” In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by P. R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, and J. Malley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157926.001.

Jansson, Janet K., and Kirsten S. Hofmockel. 2020. “Soil Microbiomes and Climate Change.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 18 (1): 35−46. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-019-0265-7.

Jansson, Janet K., and Ruonan Wu. 2023. “Soil Viral Diversity, Ecology and Climate Change.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 21 (5): 296−311. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-022-00811-z.

Klein Goldewijk, Kees, Arthur Beusen, Jonathan Doelman, and Elke Stehfest. 2017. “Anthropogenic Land Use Estimates for the Holocene – HYDE 3.2.” Earth System Science Data 9 (2): 927−953. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-9-927-2017.

Lal, Rattan. 2004. “Soil Carbon Sequestration Impacts on Global Climate Change and Food Security.” Science 304 (5677): 1623−1627. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1097396.

Lal, Rattan. 2020. “Conserving Soil and Water to Sequester Carbon and Mitigate Global Warming.” Soil and Water Conservation: A Celebration of 75 Years. Soil and Water Conservation Society. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://www.swcs.org/static/media/cms/75th_Book__Chapter_23_F9276AD04A4D8.pdf.

Lange, Markus, Nico Eisenhauer, Carlos A. Sierra, Holger Bessler, Christoph Engels, Robert I. Griffiths, Perla G. Mellado-Vázquez, Ashish A. Malik, Jacques Roy, Stefan Scheu, Sibylle Steinbeiss, Bruce C. Thomson, Susan E. Trumbore, and Gerd Gleixner. 2015. “Plant Diversity Increases Soil Microbial Activity and Soil Carbon Storage.” Nature Communications 6 (1): 6707. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7707.

Laraia, Barbara A., Tashara M. Leak, June M. Tester, and Cindy W. Leung. 2017. “Biobehavioral Factors That Shape Nutrition in Low-Income Populations: A Narrative Review.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 52 (Suppl 2): S118−S126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.08.003.

Lavelle, Patrick, Alister Spain, Manuel Blouin, George Brown, Thibaud Decaëns, Michel Grimaldi, Juan José Jiménez, Doyle McKey, Jérôme Mathieu, Elena Velasquez, and Anne Zangerlé. 2016. “Ecosystem Engineers in a Self-organized Soil: A Review of Concepts and Future Research Questions.” Soil Science 181(3/4): 91−109. https://doi.org/10.1097/SS.0000000000000155.

Lehmann, Johannes, Deborah A. Bossio, Ingrid Kögel-Knabner, and Matthias C. Rillig. 2020. “The Concept and Future Prospects of Soil Health.” Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 1 (10): 544−553. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0080-8.

Ley, Ruth E., Micah Hamady, Catherine Lozupone, Peter J. Turnbaugh, Rob Roy Ramey, J. Stephen Bircher, Michael L. Schlegel, Tammy A. Tucker, Mark D. Schrenzel, Rob Knight, and Jeffrey I. Gordon. 2008. “Evolution of Mammals and Their Gut Microbes.” Science 320 (5883): 1647−1651. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1155725.

Liang, Xiaolong, Mark Radosevich, Jennifer M. DeBruyn, Steven W. Wilhelm, Regan McDearis, and Jie Zhuang. 2024. “Incorporating Viruses into Soil Ecology: A New Dimension to Understand Biogeochemical Cycling.” Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 54 (2): 117−137. https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2023.2223123.

Lozupone, Catherine A., Jesse I. Stombaugh, Jeffrey I. Gordon, Janet K. Jansson, and Rob Knight. 2012. “Diversity, Stability and Resilience of the Human Gut Microbiota.” Nature 489 (7415): 220−230. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11550.

Magdoff, Fred, and Harold van Es. 2021. “Ch 8. Soil Health, Plant Health and Pests.” In Building Soils for Better Crops. Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE). Accessed April 29, 2024. https://www.sare.org/wp-content/uploads/Building-Soils-for-Better-Crops.pdf.

Menta, Cristina. 2012. “Soil Fauna Diversity - Function, Soil Degradation, Biological Indices, Soil Restoration.” In Biodiversity Conservation and Utilization in a Diverse World, edited by Lameed Gbolagade Akeem, Ch. 3. Rijeka: IntechOpen.

Myers, Candice A., Emily F. Mire, and Peter T. Katzmarzyk. 2020. “Trends in Adiposity and Food Insecurity Among US Adults.” JAMA Network Open 3 (8): e2012767−e2012767. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12767.

Naitam, Mayur G., and Rajeev Kaushik. 2021. “Archaea: An Agro-Ecological Perspective.” Current Microbiology 78 (7): 2510−2521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-021-02537-2.

Nethery, Rachel C., Fabrizia Mealli, Jason D. Sacks, and Francesca Dominici. 2021. “Evaluation of the Health Impacts of the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments Using Causal Inference and Machine Learning.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 116 (535): 1128−1139. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2020.1803883.

Norris, Charlotte E., and Katelyn A. Congreves. 2018. “Alternative Management Practices Improve Soil Health Indices in Intensive Vegetable Cropping Systems: A Review.” Frontiers in Environmental Science 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2018.00050.

OHHLEP (One Health High-Level Expert Panel), Wiku B. Adisasmito, Salama Almuhairi, Casey Barton Behravesh, Pépé Bilivogui, Salome A. Bukachi, Natalia Casas, Natalia Cediel Becerra, Dominique F. Charron, Abhishek Chaudhary, Janice R. Ciacci Zanella, Andrew A. Cunningham, Osman Dar, Nitish Debnath, Baptiste Dungu, Elmoubasher Farag, George F. Gao, David T. S. Hayman, Margaret Khaitsa, Marion P. G. Koopmans, Catherine Machalaba, John S. Mackenzie, Wanda Markotter, Thomas C. Mettenleiter, Serge Morand, Vyacheslav Smolenskiy, and Lei Zhou. 2022. “One Health: A New Definition for a Sustainable and Healthy Future.” PLOS Pathogens 18 (6): e1010537. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1010537.

Oldeman, L. R., R. T. A. Hakkeling, and W. G. Sombroek. 1991. ISRIC Report 1990/07: World Map of the Status of Human-induced Soil Degradation. An Explanatory Note. Global Assessment of Soil Degradation. ISRIC. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.isric.org/sites/default/files/isric_report_1990_07.pdf.

Ottman, Noora, Lasse Ruokolainen, Alina Suomalainen, Hanna Sinkko, Piia Karisola, Jenni Lehtimäki, Maili Lehto, Ilkka Hanski, Harri Alenius, and Nanna Fyhrquist. 2019. “Soil Exposure Modifies the Gut Microbiota and Supports Immune Tolerance in a Mouse Model.” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 143 (3): 1198−1206.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2018.06.024.

Pepper, Ian L., and John P. Brooks. 2021. “25 - Soil Microbial Influences on ‘One Health.’” In Principles and Applications of Soil Microbiology, 3rd edition, edited by Terry J. Gentry, Jeffry J. Fuhrmann, and David A. Zuberer, 681−700. Elsevier.

Philippot, Laurent, Claire Chenu, Andreas Kappler, Matthias C. Rillig, and Noah Fierer. 2023. “The Interplay Between Microbial Communities and Soil Properties.” Nature Reviews Microbiology. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00980-5.

Pimentel, David, and Michael Burgess. 2013. “Soil Erosion Threatens Food Production.” Agriculture 3 (3): 443−463. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0472/3/3/443.

Pouyat, Richard, Ian Yesilonis, Katalin Szlávecz, Csaba Csuzdi, Hornung Elisabeth, Zoltan Korsos, Jonathan Russell-Anelli, and Vincent Giorgio. 2008. “Response of Forest Soil Properties to Urbanization Gradients in Three Metropolitan Areas.” Landscape Ecology 23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-008-9288-6.

Preece, Catherine, and Josep Peñuelas. 2016. “Rhizodeposition Under Drought and Consequences for Soil Communities and Ecosystem Resilience.” Plant and Soil 409 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-016-3090-z.

Prüss-Ustün, A., J. Wolf, C. Corvalán, T. Neville, R. Bos, and M. Neira. 2017. “Diseases Due to Unhealthy Environments: An Updated Estimate of the Global Burden of Disease Attributable to Environmental Determinants of Health.” Journal of Public Health 39 (3): 464−475. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdw085.

Rashid, Abdur, Brian J. Schutte, April Ulery, Michael K. Deyholos, Soum Sanogo, Erik A. Lehnhoff, and Leslie Beck. 2023. “Heavy Metal Contamination in Agricultural Soil: Environmental Pollutants Affecting Crop Health.” Agronomy 13 (6): 1521. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4395/13/6/1521.

Ribaudo, Marc, Jorge Delgado, LeRoy Hansen, Michael Livingston, Roberto Mosheim, and James Williamson. 2011. Nitrogen in Agricultural Systems: Implications for Conservation Policy. ERR-127. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

Rillig, Matthias, and Daniel Mummey. 2006. “Mycorrhizas and Soil Structure.” New Phytologist 171: 41−53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01750.x.

Rillig, Matthias C., Masahiro Ryo, Anika Lehmann, Carlos A. Aguilar-Trigueros, Sabine Buchert, Anja Wulf, Aiko Iwasaki, Julien Roy, and Gaowen Yang. 2019. “The Role of Multiple Global Change Factors in Driving Soil Functions and Microbial Biodiversity.” Science 366 (6467): 886−890. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay2832.

Ritchie, Hannah, and Max Roser. 2013. Land Use. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://ourworldindata.org/land-use [Online Resource].

Rook, Graham A. 2013. “Regulation of the Immune System by Biodiversity from the Natural Environment: An Ecosystem Service Essential to Health.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110 (46): 18360–18367. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1313731110.

Scheu, Stefan. 2002. “The Soil Food Web: Structure and Perspectives.” European Journal of Soil Biology 38 (1): 11−20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1164-5563(01)01117-7.

Seligman, Hilary K., and Seth A. Berkowitz. 2019. “Aligning Programs and Policies to Support Food Security and Public Health Goals in the United States.” Annual Review of Public Health 40 (1): 319−337. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044132.

Seligman, Hilary K., Barbara A. Laraia, and Margot B. Kushel. 2010. “Food Insecurity Is Associated with Chronic Disease among Low-Income NHANES Participants.” Journal of Nutrition 140 (2): 304−310. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.109.112573.

Seligman, Hilary K., and Dean Schillinger. 2010. “Hunger and Socioeconomic Disparities in Chronic Disease.” New England Journal of Medicine 363 (1): 6−9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1000072.

Sessitsch, Angela, Steve Wakelin, Michael Schloter, Emmanuelle Maguin, Tomislav Cernava, Marie-Christine Champomier-Verges, Trevor C. Charles, Paul D. Cotter, Ilario Ferrocino, Aicha Kriaa, Pedro Lebre, Don Cowan, Lene Lange, Seghal Kiran, Lidia Markiewicz, Annelein Meisner, Marta Olivares, Inga Sarand, Bettina Schelkle, Joseph Selvin, Hauke Smidt, Leo van Overbeek, Gabriele Berg, Luca Cocolin, Yolanda Sanz, Wilson Lemos Fernandes, S. J. Liu, Matthew Ryan, Brajesh Singh, and Tanja Kostic. 2023. “Microbiome Interconnectedness throughout Environments with Major Consequences for Healthy People and a Healthy Planet.” Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 87 (3): e00212−22. https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.00212-22.

Setälä, Heikki, and Mary McLean. 2004. “Decomposition Rate of Organic Substrates in Relation to the Species Diversity of Soil Saprophytic Fungi.” Oecologia 139: 98−107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-003-1478-y.

Sheffield, Justin., and Eric F. Wood. 2011. Drought: Past Problems and Future Scenarios. 1st edition. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781849775250.

Singh, Brajesh K., Christopher Quince, Catriona A. Macdonald, Amit Khachane, Nadine Thomas, Waleed Abu Al-Soud, Søren J. Sørensen, Zhili He, Duncan White, Alex Sinclair, Bill Crooks, Jizhong Zhou, and Colin D. Campbell. 2014. “Loss of Microbial Diversity in Soils is Coincident with Reductions in Some Specialized Functions.” Environmental Microbiology 16 (8): 2408−2420. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.12353.

Singh, Brajesh K., Hongwei Liu, and Pankaj Trivedi. 2020. “Eco-holobiont: A New Concept to Identify Drivers of Host-Associated Microorganisms.” Environmental Microbiology 22 (2): 564−567. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.14900.

Singh, Brajesh K., Zhen-Zhen Yan, Maxine Whittaker, Ronald Vargas, and Ahmed Abdelfattah. 2023. “Soil Microbiomes Must Be Explicitly Included in One Health Policy.” Nature Microbiology 8 (8): 1367−1372. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-023-01386-y.

Six, J., H. Bossuyt, S. Degryze, and K. Denef. 2004. “A History of Research on the Link Between (Micro)aggregates, Soil Biota, and Soil Organic Matter Dynamics.” Soil and Tillage Research 79 (1): 7−31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2004.03.008.

Steinauer, Katja, Antonis Chatzinotas, and Nico Eisenhauer. 2016. “Root Exudate Cocktails: The Link Between Plant Diversity and Soil Microorganisms?” Ecology and Evolution 6 (20): 7387−7396. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.2454.

Sun, Haishu, Shanxue Jiang, Cancan Jiang, Chuanfu Wu, Ming Gao, and Qunhui Wang. 2021. “A Review of Root Exudates and Rhizosphere Microbiome for Crop Production.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 28 (39): 54497−54510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15838-7.

Talukder, Byomkesh, Nilanjana Ganguli, Richard Matthew, Gary W. vanLoon, Keith W. Hipel, and James Orbinski. 2021. “Climate Change-Triggered Land Degradation and Planetary Health: A Review.” Land Degradation & Development 32 (16): 4509−4522. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.4056.

Te Vazquez, Jennifer, Shi Nan Feng, Colin J. Orr, and Seth A. Berkowitz. 2021. “Food Insecurity and Cardiometabolic Conditions: A Review of Recent Research.” Current Nutrition Reports 10 (4): 243−254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-021-00364-2.

Thakur, Madhav P., and Stefan Geisen. 2019. “Trophic Regulations of the Soil Microbiome.” Trends in Microbiology 27 (9): 771−780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2019.04.008.

Toreti, Andrea, Delphine Deryng, Francesco N. Tubiello, Christoph Müller, Bruce A. Kimball, Gerald Moser, Kenneth Boote, Senthold Asseng, Thomas A. M. Pugh, Eline Vanuytrecht, Håkan Pleijel, Heidi Webber, Jean-Louis Durand, Frank Dentener, Andrej Ceglar, Xuhui Wang, Franz Badeck, Remi Lecerf, Gerard W. Wall, Maurits van den Berg, Petra Hoegy, Raul Lopez-Lozano, Matteo Zampieri, Stefano Galmarini, Garry J. O’Leary, Remy Manderscheid, Erik Mencos Contreras, and Cynthia Rosenzweig. 2020. “Narrowing Uncertainties in the Effects of Elevated CO2 on Crops.” Nature Food 1 (12): 775−782. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-020-00195-4.

Trenberth, Kevin E. 2011. “Changes in Precipitation with Climate Change.” Climate Research 47 (1−2): 123−138. https://doi.org/10.3354/cr00953.

Trinh, Pauline, Jesse R. Zaneveld, Sarah Safranek, and Peter M. Rabinowitz. 2018. “One Health Relationships Between Human, Animal, and Environmental Microbiomes: A Mini-Review.” Frontiers in Public Health 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00235.

Trivedi, Pankaj, Jan E. Leach, Susannah G. Tringe, Tongmin Sa, and Brajesh K. Singh. 2020. “Plant–Microbiome Interactions: From Community Assembly to Plant Health.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 18 (11): 607−621. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-0412-1.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2022. Nation’s Urban and Rural Populations Shift Following 2020 Census. U.S. Census Bureau. Last Modified March 21, 2023. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2022/urban-rural-populations.html.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. n.d. “Healthy People 2030.” Accessed April 29, 2024. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health.

USDA–NASS (U.S. Department of Agriculture–National Agricultural Statistics Service). 2019. 2017 Census of Agriculture: Specialty Crops. Volume 2, Subject Series, Part 8. USDA. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/Online_Resources/Specialty_Crops/SCROPS.pdf.

Usher, Kareem M. 2015. “Valuing All Knowledges Through an Expanded Definition of Access.” Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 5 (4): 109−114. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2015.054.018.

Usyskin-Tonne, Alla, Yitzhak Hadar, Uri Yermiyahu, and Dror Minz. 2021. “Elevated CO2 and Nitrate Levels Increase Wheat Root-Associated Bacterial Abundance and Impact Rhizosphere Microbial Community Composition and Function.” The ISME Journal 15 (4): 1073−1084. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-00831-8.

Valdes, Ana M., Jens Walter, Eran Segal, and Tim D. Spector. 2018. “Role of the Gut Microbiota in Nutrition and Health.” BMJ 361: k2179. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2179.

van Bruggen, Ariena H. C., Erica M. Goss, Arie Havelaar, Anne D. van Diepeningen, Maria R. Finckh, and J. Glenn Morris. 2019. “One Health - Cycling of Diverse Microbial Communities as a Connecting Force for Soil, Plant, Animal, Human and Ecosystem Health.” Science of the Total Environment 664: 927−937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.091.

Veresoglou, Stavros D., Baodong Chen, and Matthias C. Rillig. 2012. “Arbuscular Mycorrhiza and Soil Nitrogen Cycling.” Soil Biology and Biochemistry 46: 53−62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.11.018.

Vorholt, Julia A. 2012. “Microbial Life in the Phyllosphere.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 10 (12): 828−840. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2910.

Wagg, Cameron, Yann Hautier, Sarah Pellkofer, Samiran Banerjee, Bernhard Schmid, and Marcel G. A. van der Heijden. 2021. “Diversity and Asynchrony in Soil Microbial Communities Stabilizes Ecosystem Functioning.” eLife 10: e62813. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.62813.

Wang, Fayuan, Quanlong Wang, Catharine A. Adams, Yuhuan Sun, and Shuwu Zhang. 2022. “Effects of Microplastics on Soil Properties: Current Knowledge and Future Perspectives.” Journal of Hazardous Materials 424: 127531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127531.

Wardle, David A., Richard D. Bardgett, John N. Klironomos, Heikki Setälä, Wim H. van der Putten, and Diana H. Wall. 2004. “Ecological Linkages Between Aboveground and Belowground Biota.” Science 304 (5677): 1629-1633. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1094875.