Exploring Linkages Between Soil Health and Human Health (2024)

Chapter: 4 Impacts of Agricultural Management Practices on Soil Health

4

Impacts of Agricultural Management Practices on Soil Health

Understanding how common management practices influence physical, chemical, and biological attributes of soil health is key to fostering sustainable agricultural production systems that balance the need to produce food with the provision of other non-food related services. In this chapter, the committee reviews indicators used to measure soil health and major categories of agricultural management practices and their effects on soil health. However, it should be noted that a practice that is appropriate in one region and cropping system may not be appropriate in another. Also, it is unlikely that a practice is universally good or universally bad. A good example is reduced tillage, where residues are often retained on the surface that reduce erosion and promote microbial biomass and soil organic matter but may also stimulate plant pathogens that reside in those residues (Kibblewhite et al. 2008).

There is great diversity in the kinds of farms and the types of farming practices implemented in the United States. To some extent, the variety is determined by factors outside the farm manager’s control, such as climate, landform, hydrology, soil type, population density of the area, distance to market, and length of growing period. Factors such as farm size and resource endowments also influence the farm enterprise undertaken. In addition, a range of management approaches differentiate U.S. farms. Common distinctions include management complexity and philosophy (e.g., conventional, organic, or regenerative; Box 4-1). Many studies have used these contrasts—particularly organic production versus conventional production—to assess effects on crop yield and soil health (e.g., de Ponti et al. 2012; Tahat et al. 2020; Wittwer et al. 2021). The problem with this approach for the committee’s task, however, is that there is overlap among these approaches. For example, an organic farm can employ frequent tillage to combat weeds, whereas a conventional farm may use conservation tillage combined with synthetic herbicide applications. As such, evaluating the effects of these production systems on soil health is not necessarily straight-forward as tillage may

reduce soil organic matter, a key variable associated with soil health. For this reason, the committee focused on effects of specific management practices, such as tillage and cover cropping, on key variables of soil health irrespective of management system.

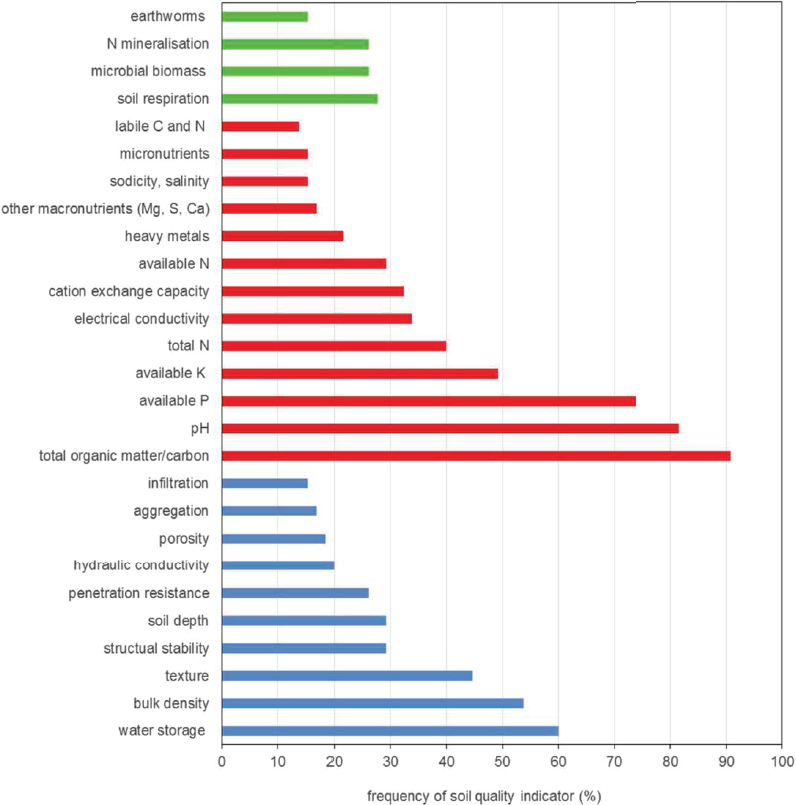

INDICATORS OF SOIL HEALTH

The health of the soil can play a major role in how resilient or resistant an ecosystem will be when challenged with disturbances due to climate change, land use change, and other pressures. A healthy soil suppresses pathogens, sustains biological activities, decomposes organic matter, inactivates toxic materials, and recycles nutrients, water, and energy (Tahat et al. 2020). However, assessing a soil as “healthy” is complex, site-specific, and hotly debated (Letey et al. 2003; Ritz et al. 2009). There are numerous soil variables that can be measured (Figure 4-1), and it is not always clear which ones best correspond to the concept of soil health and how they should be compiled and compared (Karlen et al. 2019). Indicators need to be sensitive to variations in management, correlate with soil functions that allow assessments of specific ecological processes in different land uses or ecosystems, be accessible to many users, and allow for comparisons among soils. For example, frequently measured variables, such as microbial biomass and soil respiration, clearly relate to pool sizes and carbon cycling but may be less informative in context outside these gross measurements (Ritz et al. 2009; Bünemann et al. 2018). Additional considerations for indicators relate to sample collection and handling, as well as analytical cost and reproducibility. Lastly, recognizing that each specific soil has inherent characteristics determined by climate, topography, living organisms and parent material, setting universal target values for soil health indicators in absolute terms is likely unproductive (Lehman et al. 2015). Instead, values need to be compared to appropriate reference communities and preferably measured over time to assess responses to shifts in management.

Of all indicators used, the most common is soil organic matter (Karlen et al. 2019). This fact is not surprising because small increases in soil organic matter can have cascading effects and promote aggregate stability, increase water- and nutrient-holding capacity, and boost soil fertility and microbial biomass (Lehman et al. 2015). It is clear, however, that no single measurement could evaluate all aspects of soil health, and assessments frequently include multiple variables, such as microbial biomass, mineralizable nitrogen, aggregate stability, electrical conductivity, pH, water-holding capacity, bulk density, infiltration rate, and inorganic nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (Figure 4-1). Bagnall et al. (2023) argued recently for a minimum suite of indicators for use in North American agricultural systems—soil organic C concentration, aggregate stability, and 24 h C mineralization potential—based on the breadth of information they provide about the effect of soil health management practices as well as their scalability and affordability. Efforts such as this to pare down the suite of indicators used in large-scale or producer-focused soil health assessments are valuable to reduce the cost and increase the scope of monitoring, although researchers continue to select indicators for studies based on the measurements that are most appropriate to address specific research questions.

BOX 4-1

Terminology Characterizing Farming Systems

Farming systemsa are often broadly categorized based on the types of crops grown, the spatial and temporal patterns of cultivation, and the philosophy informing agricultural management practices. There is a high degree of overlap and variety of management practices between and within systems, and farmers often use a combination based on local conditions and specific needs. Below is a nonexhaustive list that briefly describes terms discussed in this report.

Spatial Patterns of Cultivation

Cropping systems vary based on the spatial distribution of crops. Common distributions include:

- Monoculture: This strategy represents the simplest cropping system where a single crop is grown in a field within a cropping cycle. It is probably also the most used method in the United States as conditions can be optimized for a single species. However, because a single species is grown, this system is more susceptible to pests and diseases than other cultivation patterns.

- Polyculture: Multiple crops are grown simultaneously, which promotes biodiversity and reduces risk of pest and disease outbreaks. Yield per acre may increase due to complementary interactions among crops, and weed pressure may be reduced due to less open space. However, management and harvest may be complicated due to crop-specific requirements. Intercropping, strip cropping, agroforestry, and integrated crop-livestock systems are all examples of polycultures.

Temporal Patterns of Cultivation

The timing or sequence of planting decisions is also variable. Common patterns include:

- Double cropping: This cultivation practice refers to the harvesting of multiple crops from one piece of land in the same year, typically via sequential monocropping, such as winter wheat followed by soybeans (Borchers et al. 2014). Relay cropping is a type of double cropping where a second crop is planted directly into an established crop prior to harvest to allow the second crop more time to establish instead of waiting until the first crop is harvested.

- Crop rotation: This system involves rotating crop species across seasons. If crops are not closely related, rotation can help break pest and disease cycles, reduce soil erosion, and maintain and build soil fertility by varying nutrient demands among crops and by including nitrogen-fixing legumes.

- Cover cropping/green manure: Crops are planted to cover the soil between periods where main crops are grown. The aim is to keep the soil covered by a living plant to prevent erosion, build soil structure, and provide resources to soil biota. Also, if the cover crop is a nitrogen-fixing legume, soil fertility will increase, especially if residues are incorporated into the soil. If the cover crop forms mycorrhiza, it can also maintain viability and build the abundance of mutualistic fungi that may benefit the next crop. In more arid systems, however, cover crops may use water that could adversely affect yield of the subsequent main crop (or “cash crop”).

Principles and Philosophy of Management Systems

Cropping systems may also be distinguished by the principles and philosophy of management and inputs applied. These terms are often difficult to quantitatively define, and their meanings and use are highly context dependent. For example, what is considered a “sustainable” alternative system in one region may be the conventional norm in another, and sustainable practices may become the conventional norm with time and increased adoption by farmers. This categorization of farming systems typically relies on comparing the relative intensity of inputs and the degree to which management decisions, intent, and priorities are focused on agricultural outputs or on other factors such as environmental conservation or restoration. Common categories include:

- Conventional farming: This term describes farming practices such as the application of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides and the intensive use of tillage. In many cases, this term is used to denote “business-as-usual” farming practices in contrast to sustainable or regenerative alternatives (such as conventional tillage practices broadly encompassing those that frequently or heavily disturb the soil compared to conservation tillage practices that significantly reduce or remove tillage entirely). It can produce high yields and is the most common production system in the United States. However, it may be associated with environmental degradation and low sustainability. It also frequently involves monoculture cropping where single crops are grown in a year, although usually with a rotation of other single crops in subsequent years. This type of farming can reduce biodiversity and increase susceptibility to pests and disease, which would necessitate the use of pesticides.

- Sustainable farming: This term describes systems that implement agricultural management practices intended to mitigate environmental degradation and depletion of natural resources, with a focus on sustaining agricul-

- tural productivity. “Sustainable” and “conservation” systems or practices are often used interchangeably. These terms are frequently and broadly used to contrast with conventional farming practices, such as the addition of cover crops meant to protect soil from erosion and prevent nutrient losses between cash crop seasons in contrast to the conventional absence of cover between cash crops.

- Organic farming: This way of farming avoids synthetic fertilizers and pesticides and aims to build and maintain soil health by practicing crop rotation, cover cropping, and composting. It also aims to minimize environmental degradation, promote biodiversity, and produce food in a sustainable way. While yield is often lower than in conventional farming systems, the price for produce tends to be higher, resulting in similar profit. In the United States, organic farmers can opt to complete legal requirements governed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to have their farms certified as organic. Certified farms are allowed to use the USDA organic seal to market their crops. The certification system prohibits the use of genetically modified organisms and the application of synthetic fertilizer and pesticides and sewage sludge. Some organic farmers choose to follow the USDA rules for organic production but forego certification and the use of the organic label because of the minimum 3-year time commitment to convert to USDA-certified organic production.

- Regenerative farming: This is a term coined in the 1980s to describe a holistic approach that seeks to promote agroecosystem health and resilience by focusing on practices that restore soil health, such as no-till or reduced-till, cover cropping, and rotational grazing. This farming system aims to increase carbon sequestration to build soil health, mitigate climate change, and improve the sustainability of farming by promoting nutrient cycling and water retention. While sustainable farming describes management efforts to maintain or improve agricultural productivity while conserving natural resources, regenerative farming revises this concept to draw more heavily on principles of soil health management and more explicitly prioritize restoring and enhancing natural resources and ecosystem functioning while sustaining or improving agricultural productivity (Schreefel et al. 2020). Regenerative farming currently does not have a formal USDA definition or certification system, but several third-party certification systems with differing criteria exist.b

__________________

a The farming systems described here mainly apply to crop agriculture.

b See, for example, https://www.regenerativefarmersofamerica.com/regenerative-agriculture-certifications (accessed January 31, 2024).

NOTE: N=nitrogen; C=carbon; Mg=magnesium; S=sulfur; Ca=calcium; K=potassium; P=phosphorus.

SOURCE: Used with permission of Elsevier Science & Technology Journals, from “Soil Quality—A Critical Review”, Bünemann et al., Soil Biology & Biochemistry 120, 2018; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

Soil monitoring in the United States is not yet required by law, but soil surveys are conducted by U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) agencies, specifically the Natural Resources Conservation Service and the Forest Service (Kimsey et al. 2020). However, indicators used often differ depending on agency and land use type. Outside these monitoring programs, there are two major soil health assessment approaches: (1) the Soil Management Assessment Framework (SMAF), which selects biological, physical, and chemical indicators based on ecosystem services and management objectives (Andrews et al. 2004), and (2) the Comprehensive Assessment of Soil Health (CASH), formerly known as the Cornell Soil Health Test, which is more standardized (Bünemann et al. 2018). Elements of both the SMAF and CASH frameworks were recently revised and expanded to create the Soil Health Assessment Protocol and Evaluation (SHAPE) tool that better accounts for soil and climate contexts and produces more regionally applicable soil health assessments (Nunes et al. 2021). Additional methods that consolidate variables to compare soil health in organic and conventional production systems or in response to anthropogenic pressures have also been proposed (Klimkowicz-Pawlas et al. 2019; Wittwer et al. 2021). Finally, not all tests are based on laboratory-based techniques, and visual soil evaluation methods are also available for scientists, extension specialists, and farmers (Emmet-Booth et al. 2016).

Interpretable, affordable, and accessible data are needed to establish soil health baselines and evaluate changes to soil health in response to different management practices and climate conditions. The lack of harmonized approaches within and among U.S. agencies, researchers, farmers, and analytical laboratories complicates comparisons. An inspiring approach used in the European Union is the recently developed Soil Health Dashboard,1 which allows for broad assessments of the extent of unhealthy soils and the degradation processes behind them. It consolidates measures from 15 indicators, including aspects of erosion, compaction, salinization, sealing, pollution, and nutrients, as well as loss of soil organic matter and biodiversity.

The focus on physical, chemical, and biological indicators has changed over time (Karlen et al. 2019; Yang et al. 2020). In the 1930s, soil structure was primarily measured in the United States, most likely prompted by the erosion associated with the Dust Bowl. Post−World War II, a greater emphasis was placed on physical and chemical indicators due to the increased usage and availability of tillage and synthetic fertilizers in agriculture (Lehman et al. 2015). Soil biological properties were largely omitted during most of the 20th century (Lehmann et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2023), likely to the detriment of soil health and long-term sustainability. Most of the processes essential for the functioning of healthy soils—nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, disease suppression, soil structure—are governed by the extraordinary biological diversity of bacteria, fungi, archaea, viruses, protozoa, and fauna found in soil (Delgado-Baquerizo et al. 2019). These organisms thereby play an essential role in the productivity and sustainability of agroecosystems. Recent studies, for example, have shown that increasing soil microbial diversity can promote crop yields and the ability

___________________

1 European Commission Joint Research Centre. “EUSO Dashboard.” Accessed April 29, 2024. https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/esdacviewer/euso-dashboard/.

of soils to provide multiple ecosystem functions and services (Wagg et al. 2014; Lankau et al. 2022). Therefore, microbial indicators related to biomass, activity, and diversity are increasingly used due to their ecological relevance, sensitivity, and quick response to changes in environmental conditions (Bünemann et al. 2018). Some drawbacks of biological assessments include technical constraints, requirement of specific knowledge and skills, and lack of standardized information and reference values that hinders the interpretation (Bünemann et al. 2018; Yang et al. 2020). A recent effort in California to address current practices and future directions for integrating soil biodiversity into soil health analysis for agricultural producers, policymakers, governing agencies, and stakeholders recommended soil biodiversity as a principal measure in soil health evaluation and proposed a selection framework for how to choose biodiversity indicators relevant to different contexts (CDFA 2023). Wageningen University in the Netherlands has similarly developed the web platform Biological Soil Information System (BIOSIS) to map the relationships between soil organisms and nutrient cycling, climate regulation, water regulation, and disease and pest management.2

The development of advanced molecular methods has opened what was once a black box further and has facilitated the study of nonculturable soil microbes. Using compositional or functional aspects of soil microbes as health indicators has potential (Sahu et al. 2019) as these methods can perform faster, cheaper, and possibly more informative measurements of soil biota and soil processes than many other methods. Further, network analyses, structural equation modeling, and machine learning may at some point elucidate clear links between indicators and function, although this is not yet possible (Fierer 2017). There may be three main reasons for this: (1) there is great functional overlap among taxa, (2) an unknown proportion of DNA could come from dormant microorganisms (Fierer 2017), and (3) a large proportion of soil microbes still needs to be characterized taxonomically and functionally. For example, less than 20 percent of molecular taxa found in a survey from 230 locations matched known bacterial species (Nannipieri 2020), indicating that the majority of microbial diversity is still unknown. The diversity and functionality of viruses is even more opaque; the roles phages may play in soil ecosystems is just beginning to be understood (Martins et al. 2022). As such, molecular methods that more directly target functions and link to ecosystem processes irrespective of taxon ID may be more informative than those that describe composition. Such methods, including stable isotope probing transcriptomics, metabolomics, and metaproteomics, continue to advance and could be assessed against other measures of function. They are further discussed in Chapter 7.

Technology is also changing the ease and affordability of collecting data on soil health indicators. As reviewed in the National Academies’ report Science Breakthroughs to Advance Food and Agricultural Research by 2030, a network of sensors to measure biological, chemical, and physical reactions in soil over time is not science fiction (NASEM 2019). Unfortunately, there are still challenges to solve when it comes to deploying sensors that transmit reliably and indefinitely under field conditions (NASEM 2019).

___________________

2 BIOSIS. “BIOSIS Platform.” Accessed April 29, 2024. https://biosisplatform.eu/.

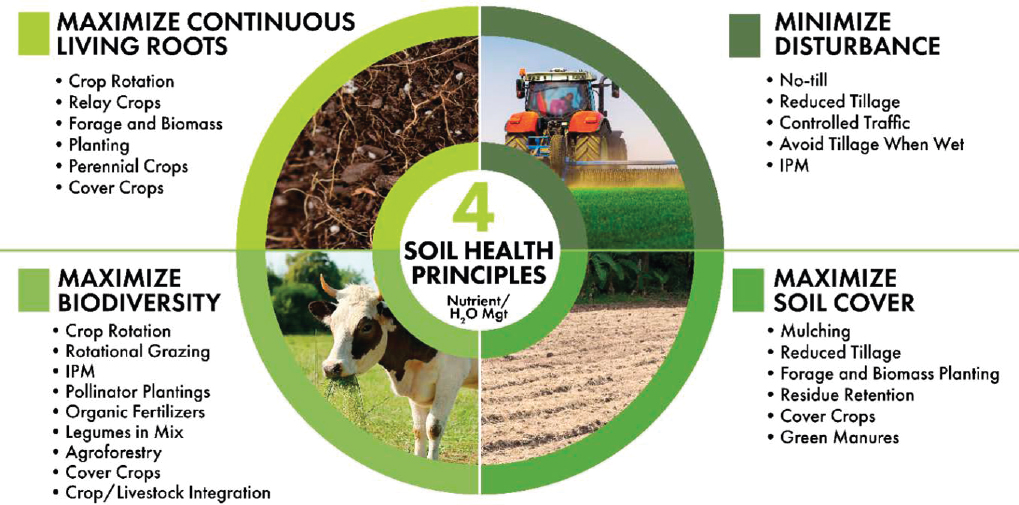

AGRICULTURAL MANAGEMENT PRACTICES

Lehman et al. (2015, 998) argued that “soil and crop management practices must: (1) maintain soil carbon, (2) control erosion, (3) maintain soil structure, (4) maintain soil fertility, (5) increase nutrient cycling efficiency, (6) reduce export of nutrients and thus the need for increased inputs, and (7) reduce pesticide input requirements and potential export of either their materials or their residuals.” These requirements broadly align with four approaches often highlighted to promote soil health, which includes maximizing continuous living roots, biodiversity, and soil cover while minimizing disturbance (Figure 4-2).

Recognizing that effects of management practices and their applicability are region and crop specific, the committee reviewed how common practices may affect key variables associated with soil health. Most research has been conducted on row crops, but the committee cites examples from other cropping systems when possible (Box 4-2).

Tillage

The practice of physically cultivating, or tilling, the soil serves many purposes. It is used to control weeds, incorporate crop residue or fertilizer into the soil, and prepare the soil for seeding. Tillage practices range widely in equipment used (from hand-hoeing to tractor-mounted equipment), frequency (never, annually, or multiple times per year), and depth (from shallow scratching for seedbed preparation or soil crust disturbance to deep plowing greater than 20 inches). These practices vary widely by location as topography, weather, soil type, and precipitation affect the timing and type of tillage used.

Conventional tillage and conservation tillage are two broad groups of practices, with a great deal of variation within each category (Claassen et al. 2018). “Conventional tillage” typically refers to practices that invert the surface layers of the soil, such as through use of a moldboard plow, that may be followed by secondary tillage to smooth or shape the soil surface. “Conservation tillage” applies to various strategies that either remove tillage entirely (i.e., “no-till”) or reduce the frequency and intensity of soil tillage (e.g., “reduced tillage,” “minimum tillage,” or “strip tillage3”) compared to conventional practices for a given cropping system (Blevins and Frye 1993).

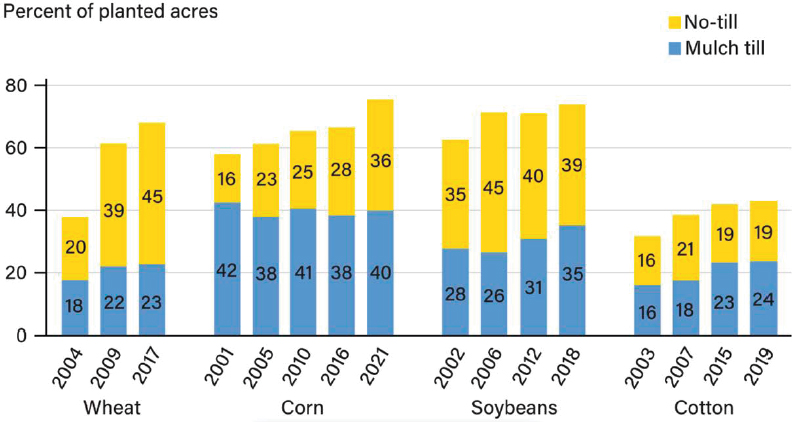

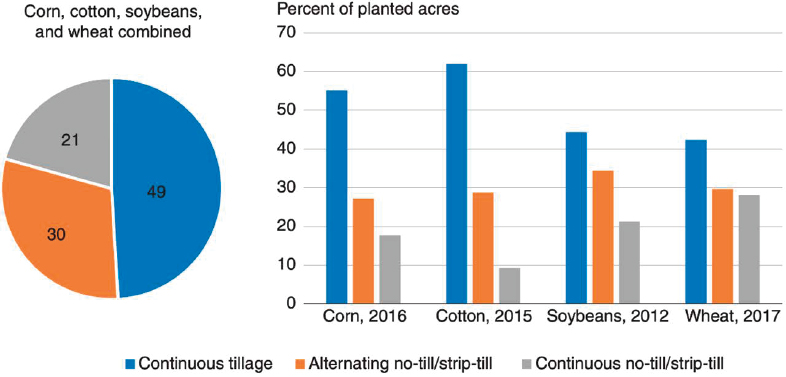

Research on conservation tillage practices began in the United States in the 1940s (Allmaras and Dowdy 1985), and such practices are used widely in the production of wheat, corn, soybean, and, to a lesser extent, cotton today (Figure 4-3). Nevertheless, survey data from USDA found that almost half of U.S. land in these crops is conventionally tilled each year (Figure 4-4). Geography and soil conditions matter, but the frequent use of conventional tillage is also partly because choices about tillage practices are closely tied with the crop that is planted and with the longer-term plan for crop rotations and land-cover management on the farm (Claassen et al. 2018).

Tillage can positively affect soil health when used judiciously in certain management systems, soil types, and climates to incorporate plant or animal residues into the soil,

___________________

3 Strip till is a type of conservation tillage practice that minimizes soil disturbance by tilling only in narrow strips of soil in which the seeds will be planted. See Claassen et al. (2018).

BOX 4-2

Urban Agriculture

While not explicitly in its statement of task, the committee felt it was important to draw attention to urban agriculture as a small but growing food production setting in the United States. Urban food production has long been important during times of distress. For example, more than 23 million U.S. families participated in subsistence garden programs during the Great Depression, and during World War II, many households grew produce for home consumption, recreation, and morale as part of the victory garden campaign (Lawson 2005). Gardening in urban and suburban areas blossomed during the Covid-19 pandemic, with noted benefits for food security and well-being (Falkowski et al. 2022).

In recent decades, there has been a resurgence in urban gardening and farming due to an increased appreciation of local food production, community-building, and a desire to increase food security (Yuan et al. 2022). In addition to produce, urban gardening has shown clear benefits to human health and well-being by providing access to nature, enjoyable physical activity, reduced air and noise pollution, and stress relief (Schram-Bijerk et al. 2018). Personal gardens also offer habitat for many plant, animal, and microbial species and have the potential to be islands of biodiversity (Goddard et al. 2010). Urban food production may also provide many regulating services, including carbon sequestration, nutrient cycling, water storage for flood control, and a reduction of heat islands (Artmann and Sartison 2018; Schram-Bijerk et al. 2018). Recognizing these many potential benefits, the 2018 Farm Bill authorized a new Office of Urban Agriculture and Innovative Production to promote urban, indoor, and other emerging agricultural practices; new pilot projects in U.S. counties with a high number of urban and suburban farms; and a competitive grants program for research and extension activities related to urban, indoor, and other emerging agricultural practices (CRS 2019).

In general, the same principles used for building soil health in rural agricultural soils (see Figure 4-2) apply in urban soils. However, food grown in urban settings may need specific strategies guided by soil tests to assess the level of potential heavy metal contamination, nutrient availability, soil organic matter, and pH, and interventions or trainings can be helpful in raising awareness of possible contamination issues to those working the soil (Hunter et al. 2019). Heavily contaminated soils would need to be either replaced—often a cost-prohibitive strategy—or capped by landscape fabric or clay that prevents mixing with noncontaminated media added on top. Soils with low levels of contamination may be amended with compost so long as compost additions do not reduce soil pH as this could exacerbate the bioavailablity of heavy metals (Murray et al. 2011; Attanayake et al. 2014). To enhance soil functions, biodiversity, and Nature’s Contribution to People, gardeners should promote plant diversity, lower management intensity, apply mulch, and avoid soil tilling as much as possible (Tresch et al. 2019). Increased collaboration between urban planners, soil biologists, and farmers is also crucial to ensure soil health is part of the urban planning policies (Guilland et al. 2018).

NOTES: In no-till production, farmers plant directly into remaining crop residue without tilling. Mulch tilling involves using instruments such as a chisel or a disk with low soil disturbance. Conservation tillage is the sum of no-till and mulch till acreage. Data reflects the year in which each crop was included in the survey.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Agriculture–Economic Research Service. “Adoption of Conservation Tillage Has Increased Over the Past Two Decades on Acreage Planted to Major U.S. Cash Crops.” Accessed April 27, 2024. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=105042.

reduce weed or pest pressure, or temporarily alleviate compacted surface or subsoil layers and increase aeration (Çelik et al. 2019; Li et al. 2019; Peixoto et al. 2020). However, the body of literature to date has shown that conventional tillage, often in combination with monoculture cropping systems, results in lower soil health through physical disturbance of soil aggregates that influences soil nutrient and carbon flow and the physical soil habitat for microorganisms and other soil fauna compared to reduced tillage or no-till systems (Nunes et al. 2020a,b; Liu et al. 2021). Lower soil organic carbon (SOC) and microbial biomass are generally observed in conventionally tilled systems compared to conservation tillage or no-till systems or undisturbed perennial systems (Nunes et al. 2020b). Long-term studies have reported lower size and stability of soil aggregates under conventional tillage compared to reduced tillage or no-till systems (Beare et al. 1994). Destroying large, stable soil aggregates through tillage has also been shown to release previously protected carbon and nitrogen into the easily available fraction, which may temporarily improve short-term plant and microbial growth but significantly depletes soil carbon and nitrogen stocks with time (Cambardella and Elliott 1993; Mikha and Rice 2004). Lower SOC combined with degraded soil structure are both linked to lower soil water-holding capacity (Bagnall et al. 2022), although a few long-term field studies have found mixed or neutral effects of tillage on soil water-holding capacity (Blanco-Canqui et al. 2017).

NOTES: Continuous tillage is continuous full-width tillage for 4 years. Survey fields grew wheat in 2017, soybeans in 2012, cotton in 2015, or corn in 2016 but could have been planted in other crops during any of the 3 years preceding the survey year.

SOURCE: Claassen et al. (2018).

Elucidating the effect of tillage on soil biota is sometimes complicated by confounding effects of other treatments. For example, no-till experiments are often combined with cover cropping where beneficial effects on soil microbiome diversity (Kim et al. 2020) may result primarily from the presence of multiple plant species and not necessarily from a lack of disturbance. Likewise, the higher bacterial diversity in no-till systems found in a recent meta-analysis (Y. Li et al. 2020) was mainly attributed to the remaining stubble, not the absence of tillage. Some decreases in bacterial diversity have been observed in response to no-till despite higher microbial biomass and activities (Tyler 2019). Nonetheless, there may be some general patterns related to soil biota effects of tillage. First, larger organisms, such as earthworms and beetles, are often more negatively affected than smaller organisms, although microbial biomass and activities are typically significantly lower under tillage as well. This decrease in microbial biomass may be driven more by fungi than bacteria because tillage disrupts fungal hyphae, especially at shallow depths (Frey et al. 1999). Not all fungi respond the same, however, and tillage may favor saprotrophic fungi that decompose residues that are incorporated, while suppressing symbiotic mycorrhizal fungi (Kabir 2005; Helgason et al. 2010; Sharma-Poudyal et al. 2017; Schmidt et al. 2019). For mycorrhizal fungi, tillage is especially damaging if done in the fall and combined with fallow, as hyphal fragments may not survive the winter to colonize emerging plant roots in the spring. This loss, in turn, may negatively influence both soil and plant health because these fungi promote aggregate stability (and thus infiltration and water-holding capacity) in soils and aid in plant nutrient uptake, drought tolerance, and pathogen protection (Kabir 2005; Delavaux et al. 2017).

Furthermore, mixing the upper soil horizons4 through tillage can reduce the stratification of carbon, microbial activities, and certain nutrients near the surface that naturally develops in undisturbed ecosystems (Prescott et al. 1995; Van Lear et al. 1995; Schnabel et al. 2000; Franzluebbers 2002) and no-till agricultural soils (Dick 1983; Melero et al. 2009; Blanco-Canqui and Ruis 2018; Blanco-Canqui and Wortmann 2020). Stratification of soil layers in previously tilled agricultural soils with poor structure that have been converted to no-till may also lead to surface or subsoil compaction in some systems (Blanco-Canqui and Ruis 2018), but this can be alleviated either in the short term with occasional tillage or in the long term by allowing soil structure and porosity to recover and develop naturally with time in no-till systems (Voorhees and Lindstrom 1984; Sidhu and Duiker 2006). Soil compaction more frequently results from heavy machinery traffic and tilling when the soil is wet in conventional tillage systems (Kirby and Kirchhof 1990).

Reduced soil structural stability from tillage can also make soils more vulnerable to wind and water erosion (Baumhardt et al. 2015). Given that the physical loss of soil by erosion is a significant ongoing threat to the soil’s ability to sustain productivity alongside negative human health outcomes of sediment inhalation from dust storms caused by erosion (see Chapter 3), slowing the rate of erosion through adoption of conservation tillage or no-till practices combined with cover cropping is a critical step in ensuring sustainable and resilient long-term agricultural production.

However, implementation of no-till practices has also been accompanied by sustainability trade-offs such as greater reliance on synthetic pesticides to combat weed and pest pressure in the absence of tillage. Increased adoption of conservation tillage and no-till has been noted as a contributing factor to the rising use of the herbicide glyphosate in agricultural systems (Benbrook 2016). Tillage is an effective strategy for controlling weeds and incorporating crop residues, whereas herbicides such as glyphosate play a key role in weed management in no-till systems. The effects of tillage and of no-till systems on animal pests (e.g., insects, birds, and nematodes) vary according to the influence of tillage on the pest species and on its natural enemies (Murrell 2020). Lower insecticide runoff in no-till systems was observed in one study (Mamo et al. 2006), presumably because the larger pore sizes in no-tilled soil allow the insecticide to enter the soil and be bound to soil minerals or organic matter or degraded by soil microbes (Shipitalo et al. 2000). This soil infiltration does not occur in no-till vegetable systems that use plastic mulch, so pesticide runoff can be extremely high in such systems (Arnold et al. 2004; Rice et al. 2007). Increased loads of herbicides and insecticides have been detected in runoff from no-till fields compared to conventionally plowed fields according to a global meta-analysis (Elias et al. 2018).

While no-till and diverse cover cropping are effective strategies for increasing soil health and stability of agroecosystems, it will be challenging to develop no-till

___________________

4 Soil forms in layers called horizons. The surface horizon is labeled A (to a depth of ~10 inches), the subsoil is B (10−30 inches deep), and the substratum is C (30−48 inches deep). Some soils may have an O or organic horizon on the surface, which may be 1−2 inches in depth. Every soil has unique combinations of horizons due to the influence of soil-forming factors and processes and may not contain all of the primary horizons described above. For more information about soil horizons, see Soil Science Division Staff (2017).

systems that are free from the use of herbicides (Colbach and Cordeau 2022; Ferrante et al. 2023). However, increased research in conservation tillage and no-till systems with novel management strategies hold potential for addressing these issues, such as implementing diverse cover crop mixes that include species with allelopathic effects on weeds (Sharma et al. 2021). Collaborative research is also underway in California to reduce tillage in organic cropping systems (Filmer 2020).

Water Management

Irrigating to provide sufficient water for crop production influences soil health. Irrigation practices range widely based on the mechanism (equipment types and gravity vs. pressure driven), location (above or belowground, localized vs. distributed irrigation), and the frequency, amount, and timing of water delivered to crops. The use of irrigation, its efficiency, and the type of crops irrigated has also varied over time in the United States (Hrozencik and Aillery 2021).

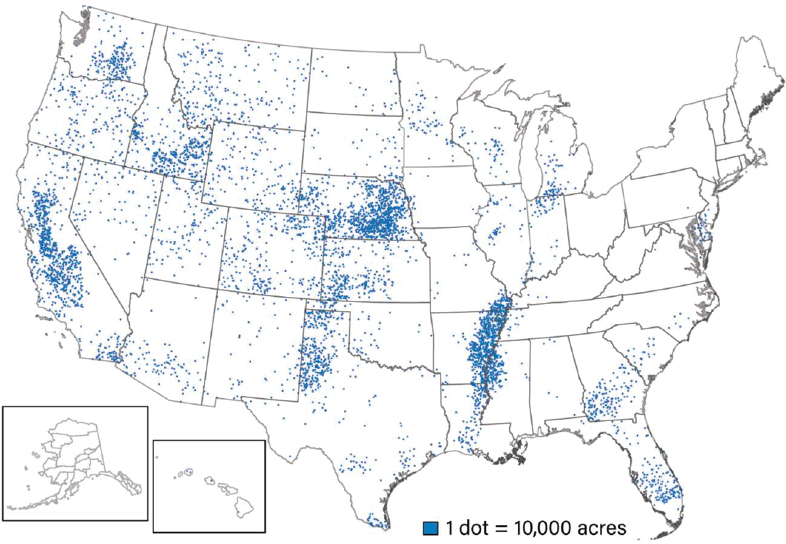

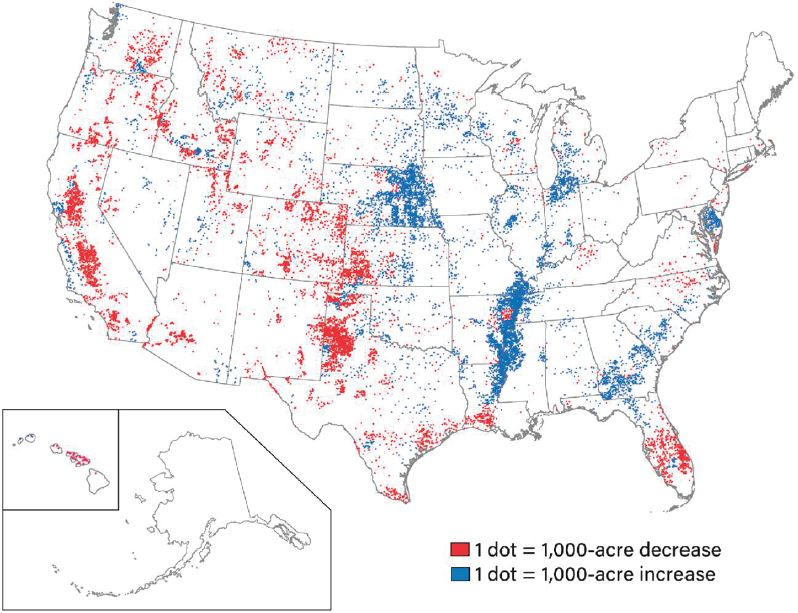

More than 54 million acres of U.S. cropland was irrigated in 2017, and irrigated harvested cropland was about 17 percent of all harvested cropland that year (Hrozencik and Aillery 2021; Figure 4-5). The impetus to irrigate depends on location and the crop being grown. For example, irrigation in the western United States is used to supplement insufficient precipitation to support crop production whereas, in the Mississippi Delta, flood irrigation supports rice production (Hrozencik and Aillery 2021). Over the past 25 years, irrigation has been moving from the West to the East as water resources for agriculture become more constrained in the West due to declining surface and groundwater resources for irrigation, reduced precipitation, and competition from nonagricultural uses while the pull to mitigate against drought in traditionally rain-fed systems has grown in the East (Figure 4-6).

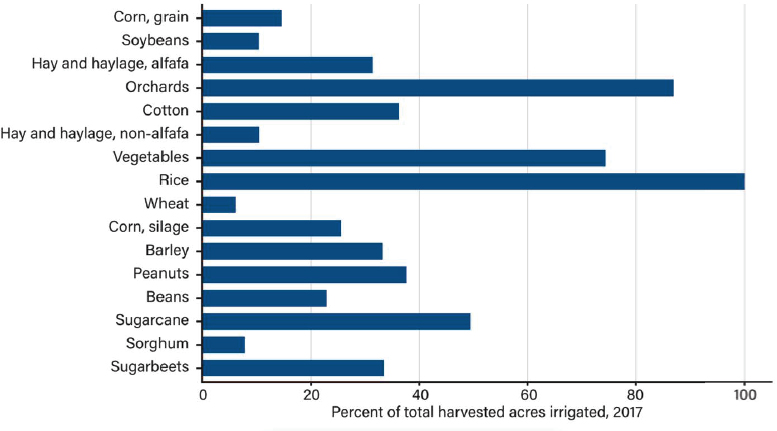

As of 2017, the crop with the most acres irrigated was corn. The 14 million acres of irrigated corn accounted for 25 percent of all irrigated acres, although that acreage was less than 15 percent of the total numbers of acres of harvested corn (Hrozencik and Aillery 2021; Figure 4-7). By contrast, 70 percent or more of the acres planted to vegetables, rice, and orchard crops are irrigated.

Researchers and land managers are continuing to develop and implement different irrigation strategies in an effort to increase crop water use efficiency, conserve diminishing water supplies, and leverage recycled water sources to sustain or increase agricultural productivity under future climate conditions. Strategies such as subsurface drip irrigation, which applies water below the soil surface using perforated flexible tubing installed along the rows, or deficit irrigation, where water is judiciously applied only during the plant growth stages where they would be most damaged by drought (e.g., during early vegetative growth or fruit ripening) can significantly increase crop yields with less water loss compared to surface irrigation or flooding (Ayars et al. 1999; Geerts and Raes 2009).

Increased plant productivity and water conservation under subsurface drip or deficit irrigation could benefit soil health and microbial communities, especially in dry climates where these resources are highly limited, but little research has focused on soil health

NOTE: Fifty-four million acres of cropland and 4 million acres of pastureland were irrigated in 2017.

SOURCE: Hrozencik and Aillery (2021).

outcomes of different irrigation methods. Studies comparing subsurface drip irrigation (which is more common in reduced tillage or no-till systems than in frequently tilled systems due to risk of damaging the drip tape during cultivation activities, unless it is buried well beneath the tillage depth) to furrow irrigation in organic tomato systems in California have revealed that subsurface drip can increase plant productivity and water savings, but at the same time may lower microbial biomass and carbon sequestration potential due to microbial responses to altered wet-dry cycles and lower macroaggregate formation (Griffin 2018; Schmidt et al. 2018; M. Li et al. 2020). While irrigated cropping systems in dry environments can potentially contribute to increased greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Sainju et al. 2008), studies have also shown significantly decreased emissions of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide under subsurface drip irrigation (Wei et al. 2018; Guardia et al. 2023). These decreases are highly beneficial in terms of reducing the GHG footprint of irrigation and crop production, but if paired with lower microbial biomass and carbon cycling in some cases as referenced above, it may also be indicative of trade-offs in microbial activities and soil health compared to more heavily irrigated agricultural systems. Some studies have shown that different inputs such as biochar or other organic amendments may be able to improve or sustain soil microbial abundance and activities under drip irrigation in arid systems (Liao et al. 2016), which shows the potential for combining certain agricultural management

NOTES: Net increase of 1,724,735 acres between 1997 and 2017. Dots represent county-level changes in irrigated acreage.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Agriculture–Economic Research Service. “Irrigated Agricultural Acreage Has Grown, Shifted Eastward, While Western Irrigated Acreage Has Declined.” Accessed April 27, 2024. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=107509.

practices with efficient irrigation strategies to alleviate potential trade-offs. Developing strategies that balance both water savings and productivity with improved soil health and carbon sequestration potential compared to systems with inefficient or higher irrigation inputs is therefore critical to achieving complimentary goals of increasing soil health and long-term agroecosystem productivity.

Irrigation-induced change in the natural water input patterns and seasonality of plant and microbial activities when natural drylands are converted to agriculture or urban systems disrupts ecosystem processes that had been adapted to, or even dependent on, water-limited conditions (Hoover et al. 2020). Biological activity and nutrient cycling in drylands typically operate in a system of pulse dynamics, where plant and microbial activities may be reduced or dormant during long dry periods, then a flush of activity occurs during rainfall events (Collins et al. 2014). In arid and semi-arid agricultural systems, irrigation to alleviate water deficits can theoretically improve soil health by sustaining plant growth and soil microbial activities through otherwise

SOURCE: Hrozencik and Aillery (2021).

dry periods because plant growth and soil biological activities rely on adequate soil moisture (Manzoni et al. 2012). Although added water in otherwise dry ecosystems can potentially increase both plant growth and microbial incorporation of residues into soil organic matter (Gillabel et al. 2007; Apesteguía et al. 2015), the outcome is not always increased SOC, especially when considering deeper soil depths (Denef et al. 2008). In addition, land use change from unirrigated natural drylands to irrigated agricultural systems are typically accompanied by tillage-induced disturbance and removal of plant residues through harvest that can lead to reduced microbial activities and carbon sequestration compared to undisturbed drylands such as native rangeland or grasslands enrolled in USDA’s Conservation Reserve Program (Acosta-Martinez et al. 2003).

The source and quality of water used for irrigation can significantly influence the relative benefits of added moisture for soil health. Accumulation of salts and water-soluble nutrients such as NO3-N in soils and groundwater resources from irrigation is of significant concern in semi-arid agricultural regions (Scanlon et al. 2010), and increased salinity or sodicity from irrigation can inhibit soil microbial activities (Rietz and Haynes 2003; Yuan et al. 2007). In an effort to conserve increasingly scarce potable water for human consumption, researchers and land managers are exploring ways to use reclaimed water (from industrial, municipal, and off-farm and on-farm animal operations) and recycled water (captured effluent from soil drainage systems) for irrigation. Recycled water was used on approximately 1 million acres, while water from reclaimed sources was used to irrigate 520,000 acres in the United States in 2018. Combined, this acreage accounted for less than 2 percent of total U.S. irrigated acreage (Hrozencik and Aillery 2021). While reusing water holds potential for improved water-use efficiency, there are also concerns with these sources. Reclaimed industrial or municipal water leveraged as a novel irrigation source frequently contains high salinity and contaminants that

potentially harm certain plants or beneficial soil microorganisms. It remains to be seen how these resources can be used sustainably or what their impacts on human health or soil health will be (Becerra-Castro et al. 2015; Miller et al. 2020).

Excessive levels of salts in even treated irrigation water are also of particular concern, especially in arid or semi-arid environments that have high soil pH and experience less frequent flushing of water through the soil profile and are thus more susceptible to salt accumulation in soils (Corwin 2021; Díaz et al. 2021). Excess salts and nutrient loads from recycled water are also a concern for sustainable water reclamation in soils that have been managed with tile drainage to prevent flooding and anaerobic conditions, as effluent tends to include high levels of salts, phosphorus, and NO3-N (Skaggs et al. 1994). However, little research has focused on the soil health outcomes of reusing tile drainage water in irrigated systems, and a recent study found no negative long-term effects of drainage water recycling on soil health (Kaur et al. 2023).

In some areas, a primary challenge to soil management is too much water rather than too little. Historically, draining soils in areas that received too much rainfall or in low-lying areas with rich soil but high water tables allowed agricultural production to flourish, including in many states across the midwestern United States. In addition to direct management of surface or subsurface drainage, other agricultural practices to improve drainage and alleviate waterlogging stress on plants include strategic deep tillage to loosen compacted subsoil layers, planting companion crops with high water demand and tolerance to waterlogged conditions, and planting earlier for some crops (such as small grains) so that they are less susceptible to early-growth damage (Manik et al. 2019). Alleviating waterlogged or poorly drained agricultural soils remains critical in many regions of the United States to improve soil aeration and nutrient cycling and to increase plant root growth and leaf photosynthetic activity to improve crop yields (Manik et al. 2019). However, drainage and conversion of wetlands to agricultural land incurs significant costs to water quality, wildlife communities, and soil health (Fausey et al. 1987). Tile draining soils for agricultural use, even in soils that are not formally classified as wetlands, can cause issues due to increased salt and nutrient loads in drainage effluent, although this also helps to prevent salt and nutrient accumulation in the soil that is being drained (Skaggs et al. 1994). Overall, extensive agricultural drainage systems that alter the natural hydrology and connections between watersheds has significantly increased nutrient loads and pollutant runoff to aquatic systems and disrupted water and nutrient cycles, which causes further issues not only for the supply and quality of water for human use but also for the health and functioning of human and natural ecosystems (Blann et al. 2009; see also the section “Nutrient Cycling and Climate Regulation” in Chapter 3).

One of the well-documented impacts of wetland drainage for agricultural production is the potential for acid-sulphate soils to form when previously reduced forms of iron and sulfur are exposed to air during drainage. After drainage, the soil pH is severely reduced, which damages both agricultural production and groundwater resources for human and agricultural use (Dent and Pons 1995). Water runoff from areas that have been subjected to wetland drainage tend to have higher salinity and nutrient loads than runoff from areas where wetlands remain intact or are restored (Fisher and Acreman

2004; Westbrook et al. 2011). Exposing wetland soils that had previously served as a sink for carbon and organic residues to air also significantly increases GHG emissions (Tan et al. 2020). In arid and semi-arid regions where groundwater is a primary source of irrigation, drainage or inhibiting wetland functionality (e.g., of “prairie potholes” in the northern U.S. Great Plains, or “playas” in the southern U.S. Great Plains) can inhibit long-term groundwater recharge and reduce water quality and quantity for human and agricultural use (Luo et al. 1997, 1999; Westbrook et al. 2011; Bowen and Johnson 2017).

Crop Choice and Rotation

The amount and form of organic material entering agricultural soils is strongly influenced by the choice and management of crops and cropping systems. Decay and incorporation of aboveground plant biomass, root growth and secretion of exudates, and root turnover are all mechanisms through which plant-derived organic material enters the soil, feeds microbial communities, and contributes to soil structure. The diversity of plant species present—across both space and time—and the extent to which land remains covered by plants and populated with live roots exert a strong influence on soil health. Depending on plant diversity and species identity, plant–soil feedbacks will also generate microbial communities that can promote or suppress yield, depending on the buildup of mutualists or crop-specific pests or pathogens. A mechanistic understanding of how plant–soil feedbacks shape long-term changes in soil health and crop productivity is key to developing new management strategies that leverage interactions between crop plants and soil biota to improve agricultural sustainability and response to climate change (Mariotte et al. 2018).

Land Cover, Biomass Input, and Living Roots

After crops are harvested, leaving crop residues (e.g., stover) on a field (with or without incorporation into the soil) can provide a valuable input of organic matter, whereas residue removal (e.g., for straw or biofuels) can accelerate depletion of soil organic matter (Wilhelm et al. 2007; Xu et al. 2019). The proportion of crop residue removed logically influences the carbon sequestered in the soil, as confirmed by a meta-analysis of corn stover removal studies (Xu et al. 2019). Across the studies analyzed, the removal of less than half the corn stover in a field resulted in SOC levels that were 1.4 percent lower than corresponding fields in which all the stover had been retained in the field, while removal of more than 75 percent of stover had SOC levels that were 8.7 percent lower. The authors indicated that “limiting stover removal to a low level (e.g., 30–40 percent) could minimize the adverse impacts of stover removal on SOC, as is currently the recommended practice” (Xu et al. 2019, 1227).

Cover crops5 can serve as an additional source of biomass input while also taking up and retaining nutrients in the agroecosystem, protecting and anchoring soil during periods between cash crops when the soil might otherwise be exposed to wind and water erosion, and supporting soil microbial communities (Dabney et al. 2001). For example, cover cropping to shorten duration of fallow has been found to promote the abundance of mycorrhizal fungi across a range of studies, which in turn increased the root colonization, phosphorus uptake, and yield of subsequent crops (Lekberg and Koide 2005). Leguminous cover crops such as clover and vetch have the added ability to fix nitrogen via symbiosis with soil bacteria, providing a nitrogen-enriched source of organic material that can promote soil health by reducing the need for fertilizer inputs and delivering a slow release of nutrients as the biomass is decomposed by soil macro- and microorganisms (Boddey et al. 1997; Bohlool et al. 1992; Soumare et al. 2020; Wittwer and van der Heijden 2020). If added or maintained on the soil surface, they can also reduce erosion, prevent soil sealing, and suppress weeds (Blanco-Canqui and Lal 2009). For example, Brassica plants that produce glucosinolates have been shown to suppress weeds, fungal pathogens, and disease-causing nematodes, which could reduce the need for pesticides if used correctly (Haramoto and Gallandt 2004; Larkin and Griffin 2007).

Despite these potential benefits, cover crop adoption in the United States is relatively low. Only 5 percent of U.S. cropland used a cover crop in 2017 (Wallander et al. 2021). The lack of widespread adoption may be related, in part, to the modest yield reductions associated with recent adoption of cover cropping (Deines et al. 2023). The use of cover crops also varies across the country because of differences in the types of crops planted, the properties of the soil, the extension and financial assistance available in an area, and the expenses associated with cover crop seed acquisition, planting, and termination (Wallander et al. 2021). Studies of the use of cover crops in low-precipitation, dryland cropping systems have found that cover crops may deplete soil water available to cash crops and reduce yields (Adil et al. 2022; Garba et al. 2022; Kasper et al. 2022). However, despite trade-offs in water use from cover crops in dryland systems, the long-term benefits of cover crops that protect vulnerable soils from erosion and add residue and root inputs for greater soil stability and organic matter sources are a worthwhile investment for sustained productivity and soil restoration. A long-term study in New Mexico demonstrated that even when water use by cover crops decreases cash crop yield, after accounting for additional benefits of cover crops such as preventing soil erosion and contributing nitrogen from legumes, use of cover crops is more economically feasible than fallow periods between cash crops (Acharya et al. 2019). Recent work from long-term semi-arid cotton cropping systems have further shown that, although cover crops may indeed deplete soil water during the period of peak growth and around termination, cover crop presence in no-till soils consistently

___________________

5 USDA defines cover crops as “crops, including grasses, legumes, and forbs, for seasonal cover and other conservation purposes. Cover crops are primarily used for erosion control, soil health improvement, weed and other pest control, habitat for beneficial organisms, improved water efficiency, nutrient cycling, and water quality improvement” (USDA–NRCS 2019b).

and significantly increases the soil’s ability to store what little water is received from precipitation or irrigation throughout the cotton growing season and reduces overall soil water resource depletion by the cotton crop compared to conventionally tilled monoculture cotton systems (Burke et al. 2021, 2022). Trade-offs between water use and soil health benefits of cover crops in drylands can potentially be addressed and managed within different environmental contexts by regulating the timing of cover crop planting and termination and selection of cover crop species with enhanced root morphology and water use efficiency (Engedal et al. 2023; Zhang et al. 2023).

Crop lifespan and rooting depth also influence soil health. Plant roots form the foundation of the rhizosphere (see the section “Soil and Plant Microbiomes” in Chapter 2), participating in myriad dynamic interactions with soil microbiota (Venturi and Keel 2016) that influence both soil health and agroecosystem performance. As plant roots grow, they exude a variety of chemical compounds, slough off dead cells, and eventually decompose, delivering nutrient- and carbon-rich organic material directly into the soil (Nguyen 2009; Dijkstra et al. 2021). Shorter-lived crops such as annuals often have smaller, shallower root systems compared to perennial crops, and thus tend not to contribute as much organic materials to soils via rhizodeposition and root turnover (Zan et al. 2001; Monti and Zatta 2009; DuPont et al. 2014; Panchal et al. 2022). Inclusion of deep-rooted and perennial crops (such as forages) in crop rotations and fully perennial systems (such as agroforestry) can enhance soil carbon sequestration and soil health via their deeper and more well-developed root systems.

Crop Diversity

Crop diversity is declining in the United States, with consolidation to fewer species across large swaths of agricultural land (Crossley et al. 2021). This homogeneity is of concern for soil health and overall agroecosystem resilience because spatiotemporal diversity can be an important driver of soil health and ecosystem services (Tamburini et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2020). Greater diversity among crop species—and the functional niches they occupy—can enhance the diversity of soil chemical nutrients and physical structure and promote soil microbial diversity through the creation of diverse microclimates and ecological niches (Vukicevich et al. 2016; Finney and Kaye 2017; D’Acunto et al. 2018; Kim et al. 2020; Saleem et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2020). Diversity can be increased by growing multiple crops in close proximity to one another (i.e., polyculture, see Box 4-1). Various polyculture systems have been widely used throughout the history of agriculture and are still used in many smallholder cropping systems (Gliessman 1985). However, spatial diversification is currently underutilized in U.S. agriculture. By avoiding monocultures, pest, pathogen, and weed problems may be reduced as the host plants are harder to find and more of the soil is covered. Also, by occupying a greater soil depth, nitrogen losses may be reduced, and the increased productivity and functional diversity may also promote carbon and nitrogen sequestration (Bybee-Finley and Ryan 2018). While ecosystem services are likely to increase with the number of crop species, so does management complexity. Thus, there may be an optimum number of crops where services are maximized and management

complexity minimized (Bybee-Finley and Ryan 2018), and this number will likely differ depending on specific crop species, their functional complementarity, and the specific environmental conditions.

Crop diversity can also be increased temporally through crop rotation. Crop rotation has been shown to increase microbial biomass and bacterial diversity relative to continuous monoculture (Liu et al. 2023). Crop rotations can also promote soil structure (Ball et al. 2005), most likely resulting from an increased carbon input and greater microbial biomass. Overall, promoting crop diversity wherever possible should be encouraged, although it may present some logistical challenges related to management and harvest. Furthermore, successfully increasing the diversity of crops planted each season and over a number of seasons—and incorporating more perennial and cover crops—will require a commitment to plant breeding (Box 4-3).

Fallow

Unlike cover cropping, fallow is an agricultural practice that leaves the field uncropped for some time. Depending on other management practices, climate, and the type and duration of fallow, it can have profound and divergent effects on soil health. For example, in natural fallows where surrounding vegetation is allowed to colonize or where specific plants are planted as an improved fallow, soil fertility, microbial biomass, and soil structure are promoted as those plants grow, die, and decompose. Indeed, this was—and still is in many subsistence farming systems—the main management practice to rebuild soil fertility by farmers prior to synthetic fertilizers (Vågen et al. 2005). In 1986, recognizing the degree of soil degradation in many agricultural soils, USDA created the Conservation Reserve Program where farmers were paid to stop growing crops on highly erodible or environmentally sensitive land and to establish improved fallows (Hellerstein 2017). In 2023, 24.8 million acres of agricultural land was enrolled in this program (Clayton 2023). Even weedy fallows may promote soil health relative to bare soil by reducing nitrogen leaching, promoting above and belowground biodiversity, and—if mycorrhizal—promoting the abundance of mycorrhizal fungi, although legacies of weed seeds may generate another suite of problems (Wortman 2016; Trinchera and Warren Raffa 2023).

The term fallow often refers to bare soil, however. This type of fallow may be used in low-rainfall regions where crops are grown every other year to conserve soil moisture. It may also be practiced for weed control. The soil is kept bare during those periods by tillage, grazing animals, or herbicides, which leaves the soil vulnerable to wind and water erosion. For example, wind erosion associated with summer fallow fields in Washington’s dryland wheat region can amount to almost 20 kg of carbon per hectare (Sharratt et al. 2018), with negative effects on soil physical, chemical, and biological properties. For soil biota, bare soil also means no host for symbionts, no plant exudates for the rhizosphere community, and no residues for decomposers (Lehman et al. 2015). Indeed, a review of semi-arid wheat fields found that fallow consistently reduced microbial biomass and activity, particularly of fungi, relative to cover cropping (Rodgers et al. 2021). However, for similar reasons, depriving microbes of host plants can also promote soil health by disrupting pest and pathogen cycles.

BOX 4-3

Breeding for Soil Health

Beyond the choice and management of crop species in agroecosystems, soil health can be influenced by the genetics of crop plants. Breeding for resistance to pests and diseases and for competition with weeds, for instance, is not only directly beneficial in terms of plant health and productivity but can benefit soils through reduced pesticide usage, which decreases the pesticide burden on soil microbial communities.

Both traditional breeding methods and transgenic and gene-editing techniques can also improve the suitability of plants for use in soil health-promoting cropping systems. Until recently, for instance, cover crops received relatively little attention from plant breeders. Increasing efforts, however, are now being directed toward the improvement of cover crops to maximize plant biomass and integrate into no-till systems (Brummer et al. 2011; Silva and Delate 2017; Griffiths et al. 2022; Moore et al. 2023). Similarly, efforts to optimize food crops for no-till and diversified cropping systems and to develop perennial grain plants and expand biological nitrogen fixation capabilities hold potential to enhance soil health through facilitating the adoption of soil health-promoting production systems (de Bruijn 2015; Soto-Gómez and Pérez-Rodríguez 2022; Moore et al. 2023).

Of particular note when it comes to soil health is the fact that crop improvement for modern agricultural systems has traditionally focused on aboveground traits such as yield, quality, and plant shoot architecture with less emphasis placed on

Synthetic Fertilizer

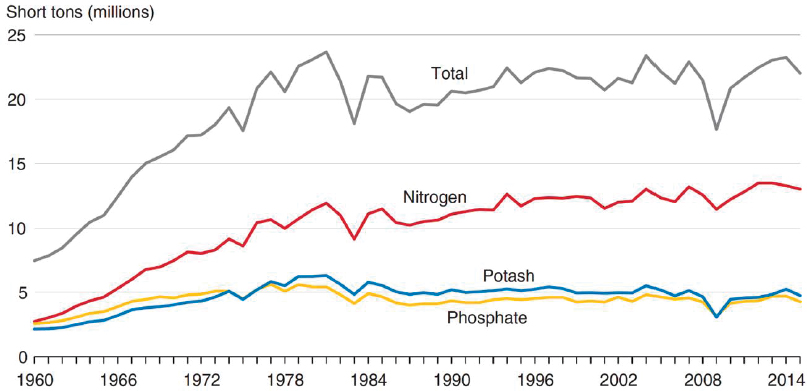

Farmers typically apply products to the soil to improve the growing conditions for their crops. Some products may replace nutrients that have been depleted from the soil. Nitrogen is often the limiting nutrient in crop production because the nitrogen in the air is not available to plants in a form they can take up without the help of microorganisms (see the section “Nitrogen Cycling” in Chapter 3). Synthetic fertilizer, which is produced by using high-energy industrial processes to convert N2 into forms of nitrogen that are available to plants, is used heavily in U.S. crop production today (Figure 4-8). Along with nitrogen, synthetic fertilizer typically contains phosphorus and potassium, two other necessary macronutrients for plants. Recent USDA survey data found that synthetic nitrogen fertilizer was applied to more than 90 percent of corn acres, nearly 70 percent of cotton acres, nearly 75 percent of wheat acres, and more than 25 percent of soybean acres.6

Although intensive use of synthetic fertilizer has enabled enormous increases in crop production over recent decades, the relationship between such fertilizer additions

___________________

6 Survey data for planted acres of corn and cotton were from 2018; for wheat and soybean, data were collected in 2017. Data available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/fertilizer-use-and-price/documentation-and-data-sources/.

belowground traits. Indeed, the domestication and breeding of modern crops has for some species resulted in unintentional shifts in root architecture and/or interactions with the rhizosphere microbiome, including possible reductions in associations with mycorrhizal fungi (Lehmann et al. 2012) and the quality of microbially mediated nitrogen fixation by some legumes (Gioia et al. 2015; Schmidt et al. 2016; Brisson et al. 2019; Martín-Robles et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2020). In most cases, these unintentional changes have resulted from indirect selection on root traits within intensive and nutrient-rich production systems.

Placing an emphasis on traits such as root system development and rhizosphere interactions within breeding programs therefore holds potential to positively influence soil health (Kell 2011; Brummer et al. 2011). Root architecture, anatomy, and physiology influence the ways in which plants explore soil profiles and capture water and nutrients as well as the ways in which they influence soil nutrients, carbon, and microbial populations (Galindo-Castañeda et al. 2022; Lynch et al. 2022). Diversity in root-related traits, which may have been lost due to the genetic bottlenecks of domestication and continued breeding, can be introgressed from wild relatives and landraces, and gene-editing techniques can be used to accelerate trait improvement (Griffiths et al. 2022). Analyses of the microbial communities associated with diverse crop genotypes are confirming that plant genetic variation can also influence rhizosphere microbial assembly (Leff et al. 2017; Yue et al. 2023). Efforts are underway, for instance, to develop cultivars with optimized root exudation that would facilitate beneficial soil microbial populations to enhance crop growth and quality (Trivedi et al. 2017; French et al. 2021).

and soil health is highly dependent on context and application rates (Singh 2018). On the one hand, when applied at or below levels where maximum yield is achieved, synthetic fertilizers can increase microbial biomass and soil organic matter by promoting plant growth and rhizodeposition, including the input of litter and root biomass into the soil (Geisseler and Scow 2014). Indeed, soil organic matter increased at the agronomic optimum nitrogen addition rate in continuous corn at four Iowa locations over a 14–16 years period (Poffenbarger et al. 2017). Where no nitrogen was added, or where excessive additions occurred, soil organic matter decreased. The suppressive effects of excessive applications may be due to altered abundances and activities of soil microbes. For example, nutrient limitations of decomposers may be alleviated, resulting in increased mineralization of soil organic matter and increased decomposition rates. Also, large amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus may suppress groups of root-associated microbes that aid plants in nutrient acquisition, such as mycorrhizal fungi and rhizobia (Zahran 1999; Treseder 2004). Effects may also be abiotic as synthetic fertilizers applied in excess can pollute soil, air, and water, cause salinization, and alter soil pH (Singh 2018; Pahalvi et al. 2021).

NOTE: Potash is the oxide form (K2O) of potassium; phosphate (P2O5) is the oxide form of phosphorus.

SOURCE: Hellerstein et al. (2019).

Organic Soil Amendments

Farmers may also apply organic products that build up depleted nutrients or enhance the physical characteristics of the soil, such as improving water retention or drainage, promoting microbial growth, improving nutrient cycling, or changing the soil’s pH. Such amendments originate from various sources (agriculture, urban, and industry), are subject to different treatments, and are added either as liquid or solid. As such, they can have very different effects on soil health (Goss et al. 2013; Urra et al. 2019). However, unlike synthetic fertilizers, they all add carbon directly to the soil that is likely incorporated into soil organic matter, resulting in improved soil structure and enhanced water- and nutrient-holding capacity. Also, all these organic sources provide microbes with carbon and energy and thus promote microbial biomass compared to soils without amendments or additions of synthetic fertilizers (Zhao et al. 2015; Dincă et al. 2022). The duration of the effects varies among amendments and type of benefits (chemical, physical, and biological) but generally ranges from less than a year to up to 10 years (Abbott et al. 2018). Biochar (pyrolized biomass), however, can remain in soil for centuries to millennia (Zhou et al. 2021).

The use of compost (or digestate if originating from anaerobic digestion) reduces fertilizer requirements and returns nutrient resources to agricultural lands, adds carbon to the soil, and lowers the cost of urban waste disposal in cases where sources are external to the farm. In 2012, Platt et al. (2014) estimated that more than 19 million tons of organic urban material, including food scraps and yard trimmings, was diverted to composting facilities in the United States, and this has likely increased since then. The

source of material being composted influences the chemical properties of the product, however, and this should be considered when assessing the potential effect on soil health (Abbott et al. 2018).

Manure is a combination of feces, urine, and animal bedding with the nutritional value and pH depending on the source (Goss et al. 2013; Abbott et al. 2018). It can supply essential macro- and micronutrients, but if applied in excess, it can be an environmental pollutant similar to the use of excess synthetic fertilizers (Abbott et al. 2018). Depending on the source of manure, it can also introduce heavy metals and various other contaminants, and microbes in manure can carry antibiotic resistance genes into soils if animals are routinely treated with antibiotics (Goss et al. 2013). In U.S. agriculture, manure is largely sourced from cows, pigs, and poultry and can either be removed from feeding operations and applied in another location or be deposited naturally by livestock within a grazed field system (Box 4-4). Compared to synthetic fertilizer, manure is applied to a much lesser extent. In 2020, less than 17 percent of corn acres, 4 percent of cotton acres, 2 percent of wheat acres, and 2.3 percent of soybean acres were treated with manure (Lim et al. 2023).

Municipal biosolids are a nutrient-rich byproduct of sewage treatment processes. Biosolids, also known as sewage sludge, have the potential to promote soil health as they contain macro- and micronutrients in variable quantities (Goss et al. 2013). According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), approximately 25 percent of the biosolids produced in the United States (1.15 million dry metric tons) were applied to agricultural land in 2021 (EPA 2023). However, similar to manure and compost, biosolids can contain pathogens, heavy metals, and other contaminants such as antibiotic residues, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and microplastics (Goss et al. 2013; Urra et al. 2019; see also the “Contaminant Case Studies” section in Chapter 6). The presence of these contaminants requires efficient strategies to mitigate risks associated with some organic amendments to soil while reaping the benefits they could provide (Urra et al. 2019). Current EPA requirements for land application set pathogen and heavy metal limits, but there are no thresholds for antibiotic residues, antibiotic resistance genes, PFAS, or microplastics. Thermochemical transformation of biosolids to biochar offers one pathway for reducing regulated and unregulated hazards associated with land application of biosolids (Paz-Ferreiro et al. 2018).

Biochar is of broad interest for building and maintaining soil organic carbon because it is stable over long periods of time in soils. This stability is important both for soil health and for carbon sequestration. Biochar is a carbon-rich soil amendment that is similar to charcoal and produced by pyrolysis (thermochemical transformation under low-oxygen conditions) of organic matter, which allows carbon to persist for hundreds or thousands of years. Biochar can be produced from a wide variety of organic materials, such as wood, crop residues, weeds, and biosolids. Biochar has a high surface area that enables it to take up water and nutrients, giving soil a greater ability to hold water and provide the slow release of nutrients to plants (Weber and Quicker 2018). The specific properties of the biochar depend on the feedstock and the details of the pyrolysis process (e.g., temperature and speed), which affect the surface area and chemistry and thus its effects on soils. Biochar can make nutrients more available to plants (Gao et

BOX 4-4

Livestock and Soil Health

The presence of livestock and poultry in agricultural systems can influence soil health both directly and indirectly. Well-managed grazing can stimulate plant growth and root development, facilitate nutrient cycling via the deposition of feces and urine, and foster ecosystem diversity in pasture and rangelands—all of which can benefit soil health. Such systems are often known as “rotational grazing” and are characterized by short periods of intense herbivory followed by longer periods of regrowth (Byrnes et al. 2018; Derner et al. 2018; Teague and Kreuter 2020). Continuous or poorly managed grazing systems, however, can lead to notable declines in soil quality due to soil compaction (from animals treading on the same area repeatedly or when the soil is wet and particularly susceptible to compaction), erosion (due to overgrazing and subsequent exposure of the soil to the forces of wind and water), loss of forage diversity (from overgrazing of favored plant species), and imbalances in nutrient cycling (e.g., due to concentrated deposition of manure in animal congregation areas) (Borrelli et al. 2017; Byrnes et al. 2018; Xu et al. 2018).

Outside of grazing systems, confinement-based animal agriculture also exerts an influence on soil health via the rations fed to livestock and poultry. While ruminant livestock such as cattle and dairy cows may consume diets that include roughage from deep-rooted perennial forages, the vast majority of U.S. livestock and poultry rations—particularly among monogastrics such as pigs and poultry—is derived (either directly or as byproducts) from annual crops such as corn and soybean often grown in high-input, low-diversity annual cropping systems (Schnepf 2011; Picasso et al. 2022).

The spatial decoupling of animal and plant agriculture in the United States has led to local and regional nutrient imbalances, with some areas beset by nutrient pollution while carbon and nutrients are depleted in areas with intensive crop production (Flynn et al. 2023). Strategic management of “manuresheds” and the development of technologies for recovering nutrients and carbon from manure can help address water pollution problems while enhancing soil health. The use of manure from animal agriculture has traditionally maintained nutrient and soil organic matter levels and continues to play an important role in soil health in contemporary dairy systems. Greater reintegration of crop and livestock production system promises to contribute to reduced pollution from livestock excreta and the improved sustainability of agricultural soils (Spiegal et al. 2020).

al. 2019) and can have a range of other positive effects on soil health, with the caveat that performance varies by soil and source of biochar (Joseph et al. 2021).

Biostimulants

Similar to the potential of probiotics and prebiotics to enhance human health (Kerry et al. 2018), there is an increasing interest in various microbial soil amendments to promote soil and crop health and productivity (Rouphael and Colla 2020). Types of amendments include (but are not limited to) N2-fixing bacteria, mycorrhizal fungi, disease-suppressing microorganisms, and less-specialized rhizosphere bacteria as well as amino acids, chitosan, seaweed extracts, compost teas, and humic substances. In the United States, the biostimulant market has grown exponentially in the last decade, and globally it is estimated to reach $4.14 billion by 2025 (Madende and Hayes 2020). A plant biostimulant is described as “a substance or microorganism that, when applied to seeds, plants, or the rhizosphere, stimulates natural processes to enhance or benefit nutrient uptake, nutrient efficiency, tolerance to abiotic stress, or crop quality and yield” (USDA 2019). It is also assumed that biostimulants are added in small quantities and that crop benefits are unrelated to the biostimulant’s nutrient content (Rouphael and Colla 2020).

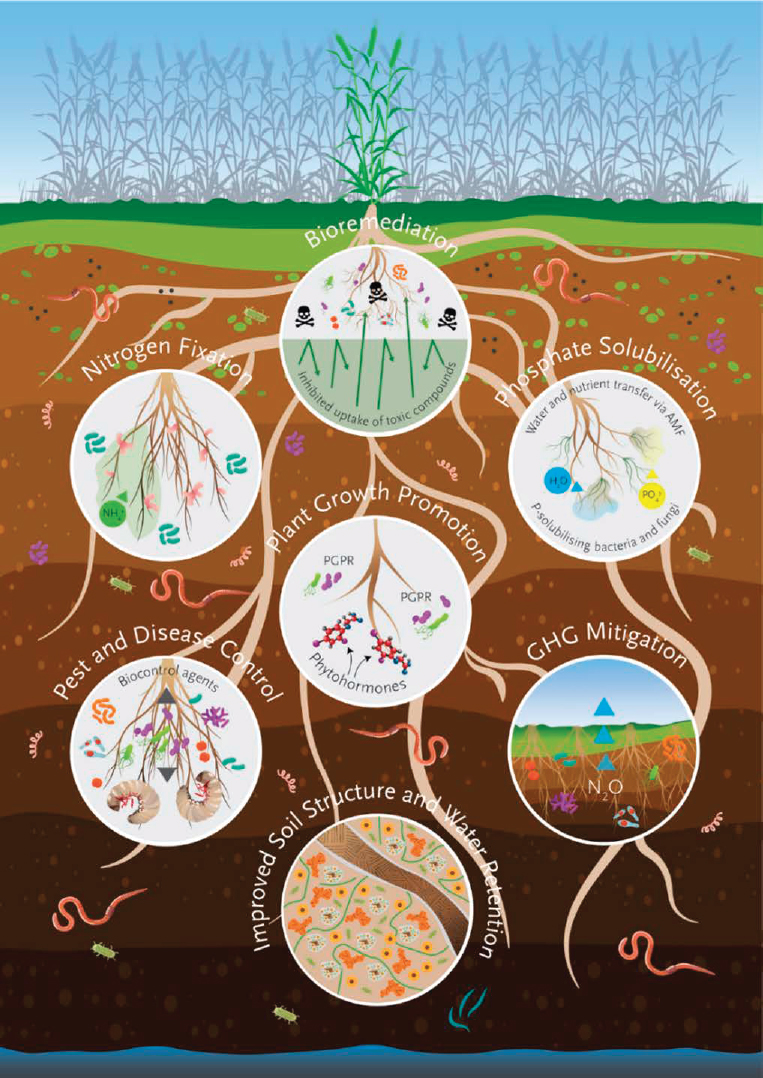

As discussed in Chapters 2 and 3, microorganisms cycle and sequester carbon and nutrients, suppress disease, and alleviate abiotic stresses in plants, produce phytohormones, degrade pollutants, and promote soil aggregation and water infiltration. While healthy soils may host at least 1 billion bacterial cells and 100 meters of mycelia per gram of soil that provide many important functions (Figure 4-9), detrimental management practices may have resulted in loss of many taxa and reduced overall abundance (Hart et al. 2017; Wittwer et al. 2021). Due to this loss, and because microorganisms are increasingly viewed as supplements to synthetic fertilizer and pesticides (e.g., Ahmad et al. 2018), the interest in microbial inoculations of single strains or diverse consortia has increased dramatically (O’Callaghan et al. 2022). Large investments by venture-backed companies in anything from naturally occurring to genetically engineered and custom-made microbes have followed this interest (Waltz 2017).