Exploring Linkages Between Soil Health and Human Health (2024)

Chapter: 5 Linkages Between Agricultural Management Practices and Food Composition and Safety

5

Linkages Between Agricultural Management Practices and Food Composition and Safety

As discussed in Chapter 1, there has been an interest in establishing a link between the health of soils and the healthfulness of the food produced on those soils. The 1993 National Academies report on soil and water quality raised this possibility, observing that some researchers had “suggested that soil quality has important effects on the nutritional quality of the food produced in those soils but noted that these linkages are not well understood and that research is needed to clarify the relationship between soil quality and the nutritional quality of food” (Parr et al. 1992 in NRC 1993, 40−41). Thirty years later, this question is still being asked. Therefore, one of the tasks set forth for the committee was an investigation of the evidence for linkages between agricultural management practices and the nutrient density of foods for human consumption, as well as other effects on food that were unspecified. This chapter looks at the evidence for connection between these practices and the nutrient density of the food produced. It then reviews the impact of food processing on the nutritional value of food. The chapter also covers the connections between agricultural management practices and food safety. Finally, it summarizes the effect of consumer choices on food production decisions, which can impact both soil health and human health.

LINKING AGRICULTURAL MANAGEMENT PRACTICES TO NUTRIENT DENSITY

There is a common perception that healthy, well-managed soils produce healthier foods; however, the connection is not always clear. Nutrient availability in the soil, environmental conditions, management practices, and plant genetics all play a part in determining nutrient density in the food supply. What ultimately determines the nutritional quality of food crops or forages (Box 5-1) is the amount of nutrients that are transported to or synthesized within the edible portion of the plant. Essential nutrients of

interest are minerals that are absorbed by fine roots and translocated to leaves, storage roots/tubers, and/or seeds, as well as biosynthesized macromolecules such as amino acids/proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and vitamins (Grusak and DellaPenna 1999). Absorbed minerals play a key role as primary nutrients in foods but also are important co-factors in numerous enzymatic and photosynthetic processes, which enable the synthesis of various essential macromolecules and potential health-promoting phytochemicals (White and Broadley 2009; White et al. 2012), the latter being potentially beneficial but not essential for human health.

Variation in nutritional quality is highly dependent on plant genetics. Numerous studies of crop genetic diversity have shown broad ranges in nutrient density or concentration, including for protein (Katuuramu et al. 2018), lipids (Attia et al. 2021), vitamins (Jiménez-Aguilar and Grusak 2017), and minerals (Farnham et al. 2011; McClean et al. 2017; Qin et al. 2017; Vandemark et al. 2018). While this variation does exist, it can only be demonstrated to its fullest when the raw materials (e.g., minerals, water) are available in sufficient quantities to meet the genetic potential of each crop cultivar. If the raw materials are limiting in soil, only those genotypes with higher absorption potential can accumulate them to adequate or higher levels. Thus, the ability of soils to provide these materials (especially minerals) has a significant impact on the nutritional quality of food.

Nutritional quality is also dependent on crop yield. Values of nutrient quality (or density) are generally expressed as a concentration; thus, they are calculated on a weight basis (e.g., dry weight basis for grains; fresh weight basis for fruits and vegetables). The overall yield of a crop has relevance because, when changes in genetics, environment, or management practices lead to increased yields, those increases can negatively affect the concentration of certain nutrients through a dilution effect (Miner et al. 2020). A dilution effect can occur because all nutrients do not necessarily accumulate within edible plant tissues at the same rate. When macromolecules such as starch or protein are increased in a harvested tissue (e.g., adding weight per seed) and the accumulation of micronutrients such as minerals or vitamins do not increase similarly, the concentration or density values of the micronutrients will be reduced.

Agricultural management strategies that lead to crop yield increases are of course welcomed and important for their role in enhanced food security (Horton et al. 2021). Although there may be reductions in the density of certain nutrients (or health-beneficial phytochemicals), higher yields do provide more food per area of land and thus a higher overall supply of nutrients. Greater productivity has benefits to consumers through both increased availability and increased economic accessibility, as prices are likely to be lower when production is higher. In food insecure regions of the world, an availability of and ability to consume more food will help individuals meet their daily caloric and nutrient requirements, even if some nutrient densities are reduced in that food (Ritchie et al. 2018).

In a general sense, agricultural management practices can influence crop nutritional quality (or health-beneficial phytochemicals; Box 5-2), positively or negatively, through their effect on soil physical, chemical, or biological properties, which subsequently can affect mineral or water availability as well as crop yield. Comparative studies of

BOX 5-1

Effects of Management Practices on Forage Quality

This report has focused primarily on the effects of agricultural management practices and soil health on the composition of food crops consumed directly by humans. However, soils also support forage crops (in addition to some grain crops) that are consumed by livestock and that affect the quality and composition of animal food products. Because forage crops require essential minerals similar to food crops, the management practices noted in this chapter that affect the physical, chemical, or biological properties of soils will also affect the yield of forage crops and their nutritional quality (Duru et al. 2013; Barker and Culman 2020). Factors relevant to soil health will, furthermore, affect (positively or negatively) the secondary metabolite composition of forages, which subsequently has effects on the concentration of potential health-beneficial phytochemicals in animal food products (van Vliet et al. 2021).

Forages for livestock are usually grasses (Poaceae) or herbaceous legumes (Fabaceae) but also include tree legumes, perennial legumes, Brassica species, and fodder beet (Capstaff and Miller 2018). In certain parts of the world, rangeland forages are unmanaged, but more commonly rangelands are managed using practices that include fertilization, grazing, controlled burning, or a combination of these strategies. As with the food crops, these management practices can have positive effects on yield, but mixed effects on forage quality. It should be noted that forage quality for livestock (especially ruminants) not only includes nutritional composition (e.g., minerals, protein, vitamins) but also dry matter content and digestibility to support energy for animal growth and metabolic maintenance (Hatfield and Kalscheur 2020; Mertens and Grant 2020).

Some examples of management outcomes on forage quality are given here. The application of nitrogen fertilizer in a legume/corn intercropping system had a positive effect on total yield, crude protein yield, and crude fat concentration, along with decreases in the concentration of neutral detergent fiber and acid detergent fiber (Zhang et al. 2022). Decreases in neutral detergent fiber and acid detergent fiber are associated with improved forage quality. In a rangeland ecosystem containing 16 species with diverse growth forms (rosette, grass tussock, stemmed-herbs), fertilization with nitrogen and phosphorus in combination with intensive grazing (relative to non-fertilization and moderate grazing) resulted in mixed results depending on the growth form of the resident forage species (Bumb et al. 2016). Dry matter content, dry matter digestibility, nitrogen concentration, and neutral detergent fiber were all influenced by management regime, with rosettes having higher dry matter digestibility and nitrogen concentration but lower neutral detergent fiber and dry matter content than tussocks in response to fertilization and intensive grazing. Controlled burning of grasslands has also been studied as a management tool because it is known that livestock tend to prefer pastures where natural fires have burned, relative to unburned areas (Eby et al. 2014). In some ecosystems, controlled fires can provide better forage quality, but the impact is transient, lasting over only one or two seasons (Augustine et al. 2010; Gates et al. 2017).

different management regimes have been undertaken in an effort to assess the interplay of these effects on crop quality, but variations in experimental design, soil types, crop species, and environmental conditions have yielded divergent results. Unfortunately, as with most complex systems where biotic and abiotic factors are at play, the influence of a given management practice on crop yield or quality is not always predictable or consistent.

Tillage

The effects of tillage practices on soil properties and crop yield have been extensively studied (Schneider et al. 2017), but the impact of tillage on crop nutritional quality (i.e., nutrient density) has gained only limited attention. Tillage, including the incorporation of manure or crop residues, can influence soil mineral and water availability in positive or negative ways (Aćin et al. 2023), which can subsequently affect the mineral uptake and quality of crops (Gebrehiwot 2022). Different tillage practices (from no-till to deep tillage) have shown mixed effects on crop yield, with no-till often resulting in reduced yields compared to conventional tillage in cereal crops (Pittelkow et al. 2015), but duration of no-till and its site-specificity could also lead to higher yields in certain cases (Daigh et al. 2018). Similarly, a meta-analysis of deep tillage showed that site specificity could lead to higher or lower yields (Schneider et al. 2017). Unfortunately, these studies did not assess the impact of altered yield on crop nutritional quality, although a dilution effect for some minerals at elevated yields could be expected (Gebrehiwot 2022). Conversely, when tillage practices result in increased levels of organic matter (e.g., with no-till or tillage with incorporation of crop residue), this can help retain soil minerals and lead to increased mineral concentrations in grain crops (Wood et al. 2018; Shiwakoti et al. 2019). In addition, reduced tillage (i.e., less soil disturbance) has also been linked to an increase in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi colonization and higher concentrations of phosphorus in shoot tissues (Lekberg and Koide 2005).

Crop Choice and Rotation

The incorporation of crop rotations, including fallow or seasonal cover crops, can benefit soil parameters that influence soil mineral availability and/or root penetration into the soil profile (Iheshiulo et al. 2023), but how crop rotations might affect crop nutritional quality is poorly understood. The inclusion of perennial forages in a long-term wheat cropping system demonstrated mixed results on soil mineral levels and grain protein and mineral concentrations (Clemensen et al. 2021, 2022). Protein levels increased with some legume–wheat rotational combinations, but negative correlations were also found between yield and wheat grain protein and grain mineral concentrations (Clemensen et al. 2021). A cropping system study with alfalfa and spring wheat showed increased wheat grain concentrations of nitrogen, sulfur, copper, magnesium, and zinc, presumably due to increased soil availability of these minerals following the alfalfa phase of the rotation (Smith et al. 2018); however, reductions in grain nutrient concentrations were found when the cropping system combination resulted in higher

BOX 5-2

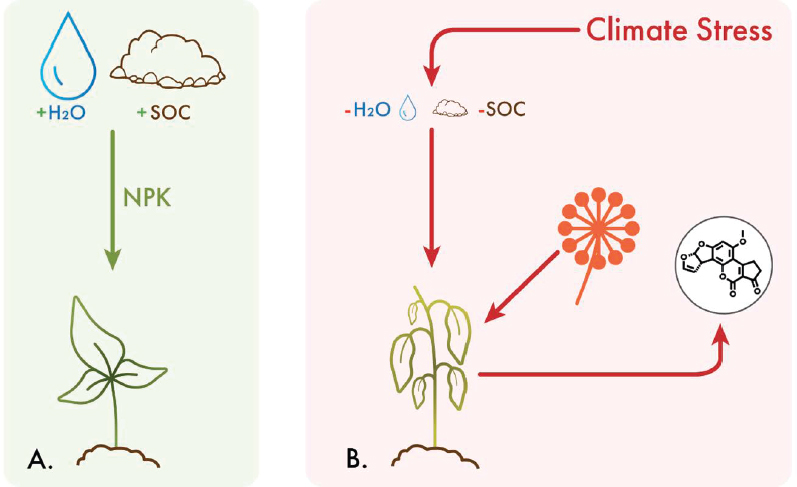

Agricultural Management Practices and Plant Bioactives

Beyond the primary nutrients, plant health will affect the production of various health-beneficial phytochemicals (also referred to as bioactive secondary metabolites)—including phenolics, alkaloids, or isoprenoids (terpenoids), among others—that are commonly associated with reduced risk of chronic diseases in humans. Some studies have demonstrated that management practices that improve soil organic carbon and microbial biomass may lead to increased levels of bioactive compounds such as phenolics and ascorbic acid in fruits and vegetables (on a dry matter basis), although such differences largely disappear when edible plant tissue yield is considered (Reganold et al. 2010). Such studies are commonly confounded by management practices not exclusively related to soil health, making it difficult to distinguish causation from correlation. For example, the link between organic farming practices and bioactive compounds accumulation in food plants has not been clearly established despite numerous studies. Some authors have reported higher levels of bioactive antioxidant accumulation in organically produced crops relative to conventional production (Barański et al. 2014), while others have reported no difference (Langenkämper et al. 2006; Mulero et al. 2010) or the opposite effect (Mishra et al. 2017). The inconsistencies could be related to the fact that the diversity of the bioactive molecules in plants is complex, and many of these compounds function as signaling or defensive molecules that can be differentially produced in response to various environmental stresses, including pests, pathogens (Adhikary and Dasgupta 2023), and ultraviolet radiation (Pfeiffer and Rooney 2015). By this token, a reduction in plant stress may lead to lower concentrations of these bioactive compounds in plant foods, due to reduced inducible biosynthesis of the compounds. However, recent evidence linking soil microbiome composition and function to plant tolerance to pathogens and diseases (Wei et al. 2019) also suggests the production of secondary metabolites as plant defense molecules may actually be enhanced in some cases in plants under healthy soil conditions. Given the important role of plant-derived bioactive compounds to human health, robust studies that credibly demonstrate the impact of soil health, as well as agricultural management practices, on phytochemical accumulation in edible plant tissue are critically needed.

yields. An analysis of 32 long-term cropping system experiments (10–63 years) across Europe and North America demonstrated that crop rotational diversity enhanced small-grain cereal yields (Smith et al. 2023). This study suggests a benefit of crop rotations on overall food production, which would contribute to human health, but data were not gathered on these rotations’ impact on crop nutritional quality.

Nutrient Application

Evidence indicates that proper timing of soil nitrogen supplementation can improve both crop yield and grain protein content in grain crops, like wheat (Hu et al. 2021). The application of nitrogen, phosphorus, or both was used in a long-term field experiment to assess effects on yield and grain quality in spring wheat (Smith et al. 2018). Fertilizer phosphorus increased grain phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, and manganese concentrations relative to controls but decreased grain zinc and calcium concentrations. Lowered grain zinc in response to soil phosphorus application has also been reported in other studies (Clapperton et al. 1997; Zhang et al. 2012; Ova et al. 2015). Reasons for this could be a suppression of mycorrhizal fungi by phosphorus fertilization (Clapperton et al. 1997) or due to reduced soil available zinc caused by precipitation with applied phosphorus (Kirchmann et al. 2009). Nitrogen fertilization in the spring wheat study (Smith et al. 2018) increased crop yields, but reduced grain concentrations of several minerals (phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, manganese, and zinc), apparently due to a dilution effect.

Other studies, however, have shown a positive effect of nitrogen fertilization and whole-plant nitrogen status on zinc concentration in wheat grains (Waters et al. 2009; Cakmak et al. 2010; Kutman et al. 2011; Shiwakoti et al. 2019). Some of the differences in these observations could be due to the level of nitrogen fertilization and nitrogen levels achieved in soils. A global meta-analysis of nitrogen fertilization effects on grain zinc and iron in major cereal crops (wheat, maize, and rice) confirmed that higher nitrogen rates generally resulted in increases in zinc and iron concentrations in these cereals, except for grain zinc in maize (Zhao et al. 2022); however, grain zinc was unchanged or reduced at lower nitrogen rates. Green manure addition and other organic soil amendment practices have been shown to enhance plant uptake of zinc, resulting in increased mineral concentrations in edible plant tissue (Aghili et al. 2014; Kumawat et al. 2023).

Fertilization effects on other nutrients have also been studied. A meta-analysis of nitrogen fertilization and water stress effects on corn grain quality (Correndo et al. 2021) showed consistent increases in grain protein levels in response to nitrogen fertilization, little impact on grain oil, and a slight reduction in grain starch, while the responses to water stress were quite variable, possibly due to large variations among the reported treatments. Nitrogen fertilization also has been shown to increase protein levels in other grain crops (Maheswari et al. 2017; Miner et al. 2018) but can lead to a dilution effect on grain oil concentrations in oilseed crops. The effect of nitrogen fertilization on vegetable crops can lead to higher protein levels in edible tissues, but elevated tissue nitrate levels can also be a human health concern (Maheswari et al. 2017). The addition

of organic matter can also indirectly improve food nutritional/health quality by reducing plant uptake of harmful heavy metals, for example, cadmium in wheat (Liu et al. 2009; see also Chapter 6).

Biostimulants

As discussed in the previous chapter, nonmicrobial and microbial soil inoculants may influence crops; in some cases, the influence in crops can in turn affect human health. These effects are a bit more nuanced rather than direct, but those connections are explored here. It may be possible to bolster micronutrient deficiencies in crops through biostimulant addition to soils (Santos et al. 2019; O’Callaghan et al. 2022). In experiments with sterilized soil in pots (corn, Kothari et al. 1990) and in the field (wheat, Rana et al. 2012), plant–microbe interactions have been shown to improve the nutritional standing of soil by enriching mineral availability and subsequently uptake by plants.

Application of beneficial microbes, such as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and mycorrhizal fungi, has been shown to increase crop yields in laboratory and field studies (Zhang et al. 2019; Chen et al. 2023). Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria can increase plant nutrient levels by altering the composition of root exudates and increasing interactions with other soil microbes (Fasusi et al. 2021). Several bacterial genera may be considered plant growth-promoting and are being studied for their roles in enhancing soil productivity, plant health, and plant stress tolerance; these include Aeromonas, Arthrobacter, Azospirillum, Azotobacter, Bacillus, Clostridium, Enterobacter, Gluconacetobacter, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, Rhizobium, and Serratia (Mannino et al. 2020; Pathania et al. 2020).

Mycorrhizal fungi can mine nutrients from the soil, enhancing plant nutrition by exploring a larger volume of soil than a plant’s root system and passing these nutrients on to the plant. The role of mycorrhizal fungi in modulating zinc and phosphorus in plants has been well studied (Cavagnaro 2008; Wang et al. 2023). Zinc deficiency is a global challenge, and many individuals experience inadequate dietary zinc intake resulting in human health issues (Brown and Wuehler 2000). Nutrients in plants increase as a result of mycorrhizal colonization of the roots, which can cause morphological and physiological changes in the roots. Mycorrhizal fungi can also increase uptake of other nutrients, and improvements in plant nutrients can occur in soils of low nutrient status or where soil nutrients are heterogeneous or depleted (Cavagnaro 2008). Soils inoculated with mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria improved nutrient uptake and plant water retention under drought conditions (Zheng et al. 2018; Bhantana et al. 2021) and may be of particular benefit because of changing climates and climate anomalies such as droughts and flooding events that can adversely affect crop production.

There is potential for biostimulants to affect overall food security by increasing crop yield and plant growth under stress and to use plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and mycorrhizal fungi inoculants to enhance specific nutrients in plants to influence human health. For instance, the application of organic soil amendments, retention of

crop residue, and use of bacteria and fungi were shown to increase rice yield, protein content percentage, and micronutrient concentration in the grain (Kumawat et al. 2023). However, as discussed in Chapter 4, the composition of biostimulants (diverse consortia vs. a single taxon), the climate and soils of the fields to which they are added, and the interactions with indigenous soil microbes are all confounding factors when it comes to understanding the degree to which biostimulants could positively affect crop nutrient density. To ensure the most practical and efficient use of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and mycorrhizal applications, it would be helpful to better understand the symbiotic relationships and metabolic pathways linking mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria with host plants (Desai et al. 2016). Use of gene-editing tools and -omics data can shed light on how the manipulation of these systems could promote growth and nutritional enhancement of crops in the future. Within these studies, it is equally important to understand the role of environmental factors in the persistence of microbial inocula under field conditions and on microbe colonization in the plant. Ultimately, the effectiveness of inoculations, both in terms of impacts on nutrient composition and economically, needs to be further tested and vetted under field conditions.

Linking Soil Micronutrient Status, Plant Micronutrient Status, and Human Nutrition

In sum, plants vary considerably in their tolerance to soil nutrient deficiencies (Impa and Johnson-Beebout 2012). Nutrient-deficient soils can have a major impact on plant growth and productivity. For example, the two micronutrients most commonly deficient in human diets globally, iron and zinc, are also associated with poor plant performance and significant yield reduction (up to 90 percent) when deficient in soil for plant growth (Alloway 2008). Furthermore, approximately 30–50 percent of heavily farmed soils around the world are deficient (content and/or bioavailability) in the key micronutrients, with the problem being more prominent in developing regions (Singh et al. 2005; Cakmak and Kutman 2018). Application of macronutrients to deficient soils (through synthetic fertilizer or other means), as widely practiced in the United States, generally improves crop yield without necessarily increasing micronutrient content of the edible part of the plant (Alloway 2009) and may sometimes have a dilution effect on food micronutrient concentrations (Cakmak and Kutman 2018). Furthermore, plant genetic traits that confer enhanced micronutrient uptake from soils do not always translate into enhanced nutrient accumulation in the edible plant tissue (Grusak 1994; Impa and Johnson-Beebout 2012).

This fact has led to a persistent challenge in identifying practical strategies to reduce micronutrient deficiency in humans through enhanced nutrient density in staple food crops, especially for at-risk populations in developing regions of the world (Pfeiffer and McClafferty 2007). Ongoing strategies, like agronomic biofortification (e.g., foliar zinc application in non-deficient soils), show promise but have produced mixed results in terms of impact on edible plant micronutrient density (Alloway 2009; Cakmak and Kutman 2018). In the context of the United States, the translocation efficiency of micronutrients from soil to edible plant tissue per se has relatively limited impact

on human nutritional status and health, largely because of widespread and low-cost micronutrient supplementation in staple products (e.g., baked goods, cereals, dairy, and beverages) as well as overall diversity of the diet. Therefore, in the United States (and other developed regions), soil micronutrient status is largely relevant primarily in its impact on food availability and affordability (via impact on crop productivity). In developing regions where nutrient supplementation is not practical among large parts of the population, the added dimension of reducing malnutrition through soil micronutrient status and plant trait development is highly significant. In a highly globalized world, this need cannot be ignored.

EFFECTS OF FOOD PROCESSING ON NUTRIENT DENSITY

Discussion of nutrient density and bioactive compounds composition in edible plant material in reference to human health and well-being is incomplete without acknowledging the processes the harvested crops must undergo before consumption. Nearly all commercially harvested plant foods are processed in some way to make them safe to consume and improve their palatability and other important attributes such as shelf life. Such processes can alter the nutritional and health attributes of the harvested material in major ways. For example, milling cereal grains to produce a more palatable and shelf-stable ingredient often involves the removal of bran and germ tissues that contain most of the bioactive secondary metabolites, dietary fiber, minerals, and vitamins. Other processes such as thermal treatment or fermentation can enhance bioaccessibility or bioavailability of some nutrients and bioactive compounds but may also lead to the degradation and loss of others. Thus, it is always important to consider the final form of edible plant tissue that is consumed when evaluating soil–plant–human health interaction.

Food processing encompasses a broad array of techniques used to transform raw agricultural commodities and other nonagricultural material into edible products or ingredients that meet end-user (consumer) needs. Food processing occurs not only at the industrial or commercial level but also at home. Familiar appliances, including home stoves, microwave ovens, refrigerators, freezers, blenders, and mixers, are used to process food at the home level. Depending on the starting raw material and intended product, the technique used in food processing can be as simple as washing and coating (e.g., fresh fruits) and thermal treatment (pasteurization, freezing) or involve a complex array of thermomechanical, physical, or electro-chemical processes and other techniques.

Regardless of the method, one of the primary goals of food processing, besides improving palatability, is to make products safe to consume by eliminating pathogens, toxins, or contaminants that may accompany harvested commodities (Box 5-3). In addition, products must provide adequate nutrition for basic human function, consistently meet consumer sensory expectations, have an adequate shelf life, offer convenience to fit busy consumer lifestyles, and remain affordable. For these reasons, food processing has been an integral part of human lifestyle for millennia. For example, techniques such as salting, dehydration, and fermentation to preserve and produce new foods

BOX 5-3

Impact of Food Processing on Nonpathogenic Microorganisms That May Be Transferred to the Human Microbiome

Food-processing technologies are directed to control microbial growth and inactivate microorganisms, including those that can make people sick. It is important to note that most food-processing methods do not sterilize the food or remove all microorganisms; thus, certain nontarget, nonpathogenic microorganisms may remain in foods after processing, while others may be intentionally introduced (e.g., through fermentation). Inactivation and control of microbes in foods is a complex issue and is affected by the nature and chemistry of the food product, as well as by the target microorganism(s). Food-processing methods are validated for a specific microorganism of interest in a specific food product, allowing survival for some microbes that may increase in number toward the end of the product’s shelf life. Naturally occurring microbes are often taken advantage of in the development of fermented vegetables, while inoculants or cultures are often added in the creation of fermented dairy products. The potential also exists for post-process contamination of food products in the food-processing facility (Teixeira et al. 2021) or elsewhere along the farm to fork continuum.

Consumers’ preference for foods that have fresh-like flavor and texture for some products has increased the use of technologies that better preserve the original attributes of a product, especially fruits and vegetables, e.g., nonthermal processing. Such nonthermally processed foods must be convenient but also have sufficient shelf-life to make distribution feasible. Examples of such processes include fresh-cut fruits and vegetables that may be combined with active packaging, high-pressure processing, ultrasound, pulsed-electric fields, ultraviolet (UV) light, and atmospheric cold plasma. These technologies, often referred to as mild processing technologies, are targeted at inactivation of microbial pathogens and are recognized alternatives to traditional thermal processing and pasteurization.a

Mild technologies may be advantageous in comparison to conventional technologies for preservation of nutritional and organoleptic properties of foods, while also ensuring safety throughout the product shelf life (Barba et al. 2017). Given the

have been in use for at least 1.7 million years (Knorr and Watzke 2019). The mastery of fermentation technology (Bryant et al. 2023) and fire for cooking approximately 1.5 million to 700,000 years ago (van Boekel et al. 2010; Herculano-Houzel 2016) enabled humans to improve food nutritional and sensory quality in unprecedented ways. Both fermentation and cooking are credited with significantly affecting human intellectual and economic development (Eisenbrand 2007; Herculano-Houzel 2016; Bryant et al. 2023).

One of the most impactful consequences of food processing is altering its nutritional profile; most processes enhance not only the palatability of the food but also the ability of humans to derive calories and nutrients from the food. In fact, invention of

potential for more frequent use of these techniques, it is likely that some microbes may survive processing and be present in a variety of food commodities. Some bacteria produce spores, which lie dormant until provided the proper environmental conditions. Spores of Bacillus and Clostridium species require the most attention, due to their inherent resistance to inactivation via processing and the innate ability of their vegetative cells to conduct metabolic activities at refrigeration temperatures. Nonthermal processing methods reduce non-spore-forming bacterial populations, but they do not inactivate bacterial spores (Markland et al. 2013).

The fate of commensal microbes in food processing is not well studied. Microbial spoilage of food is of concern given the grand challenges of wasted food, sustainability of food production, and emission of greenhouse gases from spoiled food (Xu et al. 2023). Microbial population dynamics in processing environments occur, including psychotropic and psychrophilic bacteria like Pseudomonas, Enterobacteriaceae, and lactic acid bacteria genera that grow on fresh meats, seafood, and produce. These microbes along with other genera from plant origin (Bacillus, Burkholderia, Rahnella, Pseudomonas, and Klebsiella) may be present in biofilms in production environments. Persistent and diverse microbial communities in food-processing facilities can become part of the human microbiome. A recent meta-analysis by Xu et al. (2023) showed that several nonpathogenic microbial genera are present in processing facilities, with the composition of the complex bacterial communities dependent on nutrient levels in biofilms. When tracing the connection of soil microbes through foods to human nutrition, the food-processing environment may be one worthy of future study.

a The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods revised the definition of pasteurization to include both advanced thermal (ohmic, microwave heating) as well as nonthermal lethal (high pressure, UV radiation, pulsed-electric field) agents as a part of processes leading to pasteurization (NACMCF 2006). Pasteurization is redefined as “any process, treatment, or combination thereof, that is applied to food to reduce the most resistant microorganism(s) of public health significance to a level that is not likely to present a public health risk under normal conditions of distribution and storage” (Balasubramaniam et al. 2016).

food-processing techniques enabling more efficient calorie assimilation from foods is credited with enabling the human brain to develop much faster than that of other primates (Herculano-Houzel 2016; Bryant et al. 2023). The fundamental impact of food processing on nutritional and caloric profile of foods implies that food processing is a critical and integral component to consider when examining possible linkages between agricultural management practices and the nutrient density of foods for human consumption and other effects on food.

Common Food-Processing Methods with Consequences for Nutritional Profiles of Foods

Because food processing includes a diverse array of techniques, this review contains select examples of common food-processing techniques that have a substantial effect on the nutritional and health attributes of plant-derived food commodities.

Milling

Milling, the primary method used to convert cereal grain commodities into edible or functional food ingredients, is perhaps one of the most consequential food-processing methods. Cereal grains are the most widely consumed staples around the world, directly contributing more than half of global caloric intake (Awika 2011), and milling often dramatically alters the nutritional profile of the grain, especially in terms of micronutrient and bioactive compounds profile. Regardless of the grain type or intended product, the milling process often involves separation of anatomical components of the grain, that is, the outer protective pericarp (bran), the germ, and the endosperm. The primary goal is to obtain a clean endosperm, the most abundant and economically valuable part of the grain. Grain milling leads to products like polished rice, refined wheat flour, or corn grits that can be readily used industrially or at home to make various products. Meanwhile, the milling waste stream (which mostly comprises nutrient-rich germ and bran) is, to a limited extent, used as a source of specialty ingredients for functional food applications in products such as high-fiber breakfast cereals and baked goods and rice bran oil.

Milling is integral to grain processing not only because it converts grains into more functional food ingredients but also because it considerably improves palatability of the grains; consumers have a much stronger preference for refined-grain (as opposed to whole-grain) products. The improved palatability is primarily due to the removal of the protective fibrous bran tissue that is rich in nondigestible structural carbohydrates, waxes, and secondary plant metabolites (such as phenolic compounds) that help protect the seed from pests, pathogens, and environmental assaults. The structural carbohydrates and secondary plant metabolites often negatively affect food product texture, color, flavor, and other desirable sensory attributes. However, it is important to note that these same components that negatively affect food sensory appeal are also associated with significant beneficial effects on human gut microbiome composition and metabolite production, improved gut health (Awika et al. 2018), and systemic immune response (Spencer et al. 2021), among other benefits to human health. This trade-off highlights the ever-present challenge of delivering food products with broad consumer appeal and health-promoting properties. Another important benefit of milling is improved shelf life of products by removing the germ that is rich in lipids and lipolytic enzymes that can promote lipid oxidation resulting in product rancidity.

An unfortunate consequence of modern grain milling technologies invented in the 1800s is the considerable loss of essential micronutrients (minerals and vitamins), dietary fiber, and bioactive secondary metabolites, including phenolic compounds. The vast majority of essential micronutrients derived from grains, including minerals such as zinc and iron or B-vitamins, are concentrated in the bran and germ tissues that are

removed during the milling process. Key micronutrients of concern, such as thiamin (vitamin B1), riboflavin (vitamin B2), niacin (vitamin B3), iron, and zinc, are reduced by 60–80 percent in refined (milled) grain products (Awika 2011), whereas bioactive secondary metabolites and dietary fiber are reduced by approximately 90 percent in the milling process (Awika et al. 2005; Awika 2011). Ironically, the discovery of several of the B-vitamins in the early 20th century is directly attributable to the industrialization of the modern refined milling process that led to the outbreak of vitamin deficiency-linked diseases like pellagra (vitamin B3) and beriberi (vitamin B1) (Carpenter 2000). The ubiquitous and highly successful enrichment program (incorporating predetermined levels of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B9, and iron to refined grain products) currently widely practiced by millers was encouraged by the U.S. government beginning in the 1930s to combat the negative nutritional consequences of modern grain milling processes.

In the above context, improvement of grain nutritional profile targeting micronutrients or bioactive compounds via genetic improvement or agricultural management practices to improve soil health can be a major challenge if the nutrients end up getting largely lost during the milling process. This circumstance indicates that, beyond the gross nutrient content/concentration of the resulting grain, the partitioning of the nutrients in specific tissues of the seed must be considered. In fact, the location of nutrients in different parts of the seed remains one of the major challenges in attempts to improve micronutrient profile of grains through biofortification (Díaz-Gómez et al. 2017). Furthermore, although nutritional and health benefits of whole-grain components are well documented (Cho et al. 2013; Hu et al. 2020; Hullings et al. 2020), capturing these benefits to broadly affect human health remains challenging primarily due to low consumer acceptance of such products. Therefore, deriving full benefits of nutritionally beneficial plant commodities requires innovations in methods to minimize losses of such nutrients and bioactive compounds during processing while maintaining consumer acceptance. Novel methods that enhance beneficial effects of the desirable compounds in foods at lower levels of intake (to minimize undesirable sensorial properties)—for example, by exploiting synergistic biological activities of complementary molecules or altering the food matrix for targeted release of the compounds along the gastrointestinal tract (Awika et al. 2018)—are worth pursuing. Additionally, technologies that enhance the functionality of the grain milling waste streams in mainstream food applications to improve consumer acceptance while capturing their nutritional and health benefits are critically needed.

Thermal and Mechanical Processing

As mentioned previously, the invention of thermal processing has been one of the most consequential events in the human intellectual evolution (Herculano-Houzel 2016). Furthermore, innovations in modern thermal processes such as commercial sterilization (ca. 1800) and pasteurization (ca. 1865) have dramatically affected human health and well-being by improving food product safety and quality and revolutionizing the efficiency of the food value chain. Due to its predictable impact on food safety, shelf stability, and desirable sensory effects, thermal treatment is the single most common

process food commodities undergo prior to consumption, both in industrial and home settings. Beyond safety and sensory quality, thermal processing can also have a major impact on the nutritional profile of plant material. Furthermore, the thermal process is often accompanied by varying levels of mechanical processes, including agitation, crushing, homogenization, and pressure (e.g., in extrusion process), that may further affect the nutritional and quality profiles of the food product.

In general, an important, consequential effect of thermal processing is significant improvement in the bioavailability of both macronutrients and micronutrients. The macronutrients are made more bioavailable via thermal denaturation (e.g., starch gelatinization, protein unfolding) that makes them more accessible to digesting enzymes or via deactivation of antinutritional factors present in some commodities, such as lectins and trypsin inhibitors in legumes. The micronutrients can also become more bioavailable via improved release from cellular matrices that are physically disrupted during thermomechanical processes. Processes that lead to more disruption of the plant cell wall matrix often lead to increased bioacessibility of micronutrients, including phenolic compounds and other secondary plant metabolites. Furthermore, thermal treatment can structurally degrade some antinutritional compounds (e.g., tannins and phytates), leading to enhanced micronutrient (especially iron) bioavailability (Raes et al. 2014).

However, it has to be noted that some micronutrients (e.g., ascorbic acid and some tocopherols) are not heat stable and can significantly reduce under thermal processing, especially when heat conditions are severe (exceed 110°C for several minutes), as can be encountered during canning, roasting, and extrusion. Nevertheless, it is generally recognized that common food thermal processes do not lead to catastrophic loss of the vast majority of macronutrients and that benefits of thermal processing on micronutrient bioaccessibility are more positive than negative (Dewanto et al. 2002; van Boekel et al. 2010; Ravisankar et al. 2020).

Fermentation and Germination

Crop fermentation and seed germination (often referred to as sprouting) are common processing techniques used to improve sensory and nutritional profile of plant-based crops (e.g., grain pulses and other legumes, cereal grains, and leafy vegetables) and, in the case of fermentation, shelf stability of various products (e.g., sauerkraut, kimchi, and olives). Both processes rely on partial enzymatic transformation of food components to produce secondary compounds with desirable properties, for example, acidity or volatile flavor profile. While germination relies largely on endogenous plant seed enzymes, fermentation is typically dependent on exogenous microbial enzymes. The overall nutritional consequences of exogenous or endogenous enzymes are similar. The enzyme action leads to partial hydrolysis of macronutrients (carbohydrates and proteins), making them more easily digestible by humans. At the same time, chelating antinutrients like phytates and tannins are also partially hydrolyzed (via action of phytase and tannase), which can considerably enhance bioaccessibility of micronutrients like iron (Raes et al. 2014). Partial degradation of cell wall polysaccharides by the enzymes also leads to enhanced release of micronutrients and bioactive phenolic compounds; for example,

phenolic antioxidants extractability has been shown to increase more than two-fold during fermentation of cereal grains (Ravisankar et al. 2021). Furthermore, during fermentation, the resulting low pH and organic acids produced can enhance solubility of iron and zinc, further improving their bioacessibility (Raes et al. 2014). Consumption of fermented foods has also been found to increase microbiota diversity in the human gut and reduce inflammatory markers (Wastyk et al. 2021). The diverse array of nutritional benefits derived from food fermentation is hypothesized to be one of the key early triggers of human brain development in the evolutionary process (Bryant et al. 2023). Thus, fermentation and germination are processes that can be used to help overcome some of the undesirable consequences of other processes that result in reduced micronutrient density in some food commodities. For example, a combination of sprouting with the conventional fermentation process can improve whole wheat flour functionality and whole wheat bread sensory quality (Johnston et al. 2019; Cardone et al. 2020). These technologies could be innovatively exploited to enhance the sensory appeal of whole plant-based food components (e.g., whole grains), which would in turn reduce food waste and pressure on land needed to produce more food (Box 5-4).

Challenges of Measuring Human Health Impacts in Response to Foods

There is no pragmatic option to definitively examine the relationship between consumption of foods and the resulting health impacts. Dietary guidance is based on aggregated evidence from observational and mechanistic studies plausibly linking intake of foods to health outcomes by demonstrating both (1) linkages between components of human diets and health outcomes and (2) plausible physiological mechanisms demonstrating how the relationship between consumption of foods and their constituents can be causally related to health outcomes. Additionally, studies have measured the presence of food constituents in human blood after consumption of foods or extracted components of these foods. However, controlled experiments in humans examining disease outcomes in response to diet are limited to (1) studies of dietary supplements (e.g., fish oil concentrates) and (2) interventions that alter the entire dietary intake of participants (e.g., a vegetarian dietary pattern). More typically studies must rely on so-called intermediate markers of human health such as blood biomarkers, body composition, and functional status. These measurable characteristics provide evidence of the challenges in defining healthy soils as well as healthy humans, due to the lack of standards, detectable biomarkers, and comparable metrics in some cases. Further challenges include:

- The absence of a universal measure of disease or health

- The magnitude of effects and time scale by which food influences health

- Human physiological variability (e.g., genetic variation)

- Human environmental context

- Interactions between foods and their components with other dietary aspects and lifestyle behaviors of individuals

BOX 5-4

Food-Processing Waste as a Tool to Improve Soil Health

Approximately 25 percent of food produced around the world is wasted every year (O’Connor et al. 2021), and this underutilized resource is expected to reach 2.2 billion metric tonnes globally by 2025 (Hoornweg and Bhada-Tata 2012). Plant-derived commodities account for more than 90 percent of food waste. In the United States, food processing and manufacturing account for almost 40 percent of the food waste (EPA 2023). Therefore, strategies that improve food manufacturing and handling practices can considerably reduce food waste, and in turn benefit food security as well as soil health.

Food waste leads to inefficiency in the production food value chain, which increases demand on land use to produce more food and, in turn, can accelerate soil nutrient depletion. Because food waste is primarily organic matter rich in nutrients, it can be a valuable source of nitrogen and other products for improving soil health and for soil remediation. For example, aerobic solid composting or anaerobic digestion of food wastes (Waqas et al. 2018; Cheong et al. 2020) can produce soil amendment products that improve beneficial soil microbial populations, increase soil water retention, and improve soil structure (Kasongo et al. 2011; Tampio et al. 2015; Sogn et al. 2018). Common food-processing byproducts, like cereal bran and coffee grounds, can also be recycled to directly produce other foods, for example, as substrates for mushroom production (Chai et al. 2021), further producing ecological benefits while reducing pressure on land use.

Therefore, directly measuring human health impacts of foods grown in different soils would be extremely challenging with existing research modalities.

LINKING AGRICULTURAL MANAGEMENT PRACTICES TO FOOD SAFETY

Soil ecosystems are complex and can support the persistence of zoonotic and phyto-pathogens. Some pathogens found in the soil can cause human disease through ingestion of contaminated food; others enter the body by different routes (Box 5-5). Mycotoxins are diverse small molecules produced by fungi that reside in soil and colonize crops in the field or in storage. They have deleterious health effects when consumed, but they cannot be detected by taste or smell (Winter and Pereg 2019). Agricultural management practices can influence the presence and abundance of these types of food contaminants.

BOX 5-5

Soil-Borne Human Pathogens

In addition to foodborne illness, soils harbor pathogens that can cause human disease from cutaneous wound inoculation, direct ingestion of soil (geophagy), or inhalation of dust particles. The threat to human health from some soil-borne pathogens has been mitigated in the United States with the development of vaccines. For example, the bacterium Clostridium tetani, which lives in soil and manure and causes tetanus, typically enters the body through a wound. Cases of tetanus in the United States dropped from 500–600 per year in the first half of the 20th century to no more than 100 per year since the 1970s, due to the development and uptake of a vaccine starting in the late 1940s (Tiwari et al. 2021).

Soil-borne pathogens are often widely distributed but more likely to be a health concern for only some populations. For example, the fungus Histoplasma does not make most people who inhale it sick. However, people with weakened immune systems, infants, and adults aged 55 and older are at higher risk for severe infections of histoplasmosis.a Antifungal drugs became available for the treatment of severe histoplasmosis in the 1950s (Kauffman 2007).

Histoplasma is also an example of a pathogen that is more common in some areas than others because of the soil properties of a region. In the United States, most histoplasmosis outbreaks (more than two cases with a common environmental source) between 1938 and 2013 occurred in the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys (Benedict and Mody 2016), although modeling indicates that soil environments more hospitable to Histoplasma have shifted to the upper Missouri River basin (Maiga et al. 2018).

Coccidioidomycosis, also known as Valley fever, is an example of a regionally specific soil-borne disease of growing concern in the United States. Severe disease causes lung problems; in rare cases, infection can spread to the brain, skin, and joints (Thompson 2011). The disease is caused by the fungus Coccidioides, commonly found in some of the dry, arid soils of the Southwest. People are exposed through inhalation of Coccidioides spores, and most cases reported are found in Arizona and California. There is evidence that increases in cases coincide with climate patterns (Smith et al. 1946; Park et al. 2005). There is also evidence that global warming is increasing the geographic habitat in the United States hospitable to airborne dispersal of Coccidioides spores (Gorris et al. 2019). The cause of increased Coccidioides spore dispersal and ways to mitigate exposure when dispersal is high continue to be studied.

These are organisms of concern, but this is in no way an exhaustive list of those with potential to cause disease associated with soil. Jeffery and van der Putten (2011, 8) identified 38 human diseases that result from a “pathogen or parasite, transmission of which can occur from the soil, even in the absence of other infectious individuals.” Although risk of disease from some organisms has been mitigated in the United States, as in the example of tetanus, the case of coccidioidomycosis (annual cases of which grew from an average of less than 7,000 a year for 2000–2009 to almost 15,000 a year for 2010–2019b) shows that soil-borne human pathogens are still a cause for concern.

a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Histoplasmosis: Risk & Prevention.” Accessed April 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/histoplasmosis/risk-prevention.html.

b Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Coccidioidomycosis: Statistics.” Accessed April 27, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/coccidioidomycosis/statistics.html.

Foodborne Pathogens

Pre-harvest soil content and survival and growth of zoonotic pathogens can influence the safety of crops, in particular fruits and vegetables that may be consumed raw. Of particular concern are pathogen-contaminated crops that are consumed by individuals at increased health risk, including people age 65 and older, young children (especially those 5 years of age or younger), and those who are immunocompromised, including pregnant women. It is worth noting these higher-risk individuals as this population is growing nationally. In the United States over the past two decades, several high-profile foodborne pathogen outbreaks—for example, of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., and Listeria monocytogenes—have been linked to contamination influenced by amended soils of leafy greens, peppers, cantaloupes, and cucumbers (Sharma and Reynnells 2016).

Tillage and Cover Crops

As seen in Figure 4-3, U.S. farmers are increasingly using conservation or reduced tillage practices. These practices, along with crop residues left on the soil surface rather than being incorporated into the soil, may favor pathogen (plant and zoonotic) survival by lowering soil temperature, leaving the soil undisturbed, increasing soil moisture, and providing protection from degradation (Bockus and Shroyer 1998). Tillage may be used

to disc under plants that may be suspected of harboring zoonotic pathogens because zoonotic pathogens like E. coli and Salmonella may not survive well when buried below the soil surface (Koike 2022). Some fungal plant pathogens, however, survive in soils using the durable structures that allow them to adhere to the crop; another fungal pathogen strategy is to move through soil, water, or contaminated equipment in the dead tissue of diseased plants (Koike 2022).

As discussed in Chapter 4, cover crops are used for a variety of soil health objectives. Cover crops have variable effects on enteric pathogens, whereby some may increase pathogen survival (Bultman et al. 2013), while others likely have less effect (Schenck et al. 2019).

Organic Soil Amendments

Soils are often enriched with biological soil amendments of animal origin (BSAAO) to increase nutrient values, enhance water-holding capacity, and support crop growth and yield.1 BSAAO can be delivered to soils in the form of raw animal manure, treated or composted manures, and compost teas. As discussed in Chapter 4, they promote soil structure and function, but they have been identified as a critical route of on-farm contamination of fresh fruits and vegetables (Sharma and Reynnells 2016; Teichmann et al. 2020). BSAAOs can contribute to food-safety risks as they may: (1) be contaminated with zoonotic pathogens and (2) enhance the growth of zoonotic pathogens in and around the growth of raw agricultural commodities. Understudied liquid fertilizers and organic emulsions may influence the growth of pathogens in the soil depending on how they are processed (Ingram and Millner 2007; Mahovic et al. 2013; Jung et al. 2014). These are considered raw or untreated fertilizers if nutrients (e.g., molasses, yeast extract, algal powder) are added to a manure-based agricultural tea to increase the microbial biomass, according to the Food Safety Modernization Act-Produce Safety Rule implemented by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (FDA 2015).

In raw animal manure, the manure type, the method of application or incorporation into soils, the type of soil, storage of manure before application on to soils, and the microbial diversity present and nutrient ratios in manure-amended soils can affect the persistence of bacterial and viral pathogens (Avery et al. 2004; Hutchison et al. 2005; Franz et al. 2008). It is important that growers use soil amendments appropriately for crop health and to minimize the risk of excess soil amendments leaving the field through runoff and entering produce fields.

Management of soil amendments can reduce food-safety risks. Risk reduction approaches include assessing risks from the soil amendment being used, selecting low-risk crops for application (e.g., agronomic crops such as corn, soybeans, and wheat), and reviewing the application method (incorporated, injected, or surface applied) and

___________________

1 “Biological soil amendment of animal origin means a biological soil amendment which consists, in whole or in part, of materials of animal origin, such as manure or non-fecal animal byproducts including animal mortalities, or table waste, alone or in combination. The term ‘biological soil amendment of animal origin’ does not include any form of human waste” (21 CFR 112).

timing (days to harvest; season of application). Raw manures, for example, are more often applied to agronomic crops rather than to crops that may be consumed raw (e.g., vegetables).

In the United States, the practice of applying animal-origin raw or treated manure in the crop field as a part of nutrient management plan may include application of manure from cattle, poultry, or other mixed manures (Pires et al. 2018). The FDA’s Produce Safety Rule focuses on minimizing microbiological safety risks associated with application of treated or raw manure in the growing season for fresh consumed crops (FDA 2015). The rule states that there should be no contact between applied manure and the edible portion of the crop at any point of production, from planting to harvest. FDA has not yet published wait-time intervals between manure application and crop harvest and is continuing to assess the data collected (FDA 2015); however, producers can follow guidance published from the National Organic Program of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which states a time period of 120 days from application of manure to harvest of crops (USDA 2011). Nonpathogenic strains of E. coli are predominantly studied in laboratory and field trials and are used to indicate fecal contamination as well as for their potential to indicate pathogen survival in soils. Research has corroborated the 120-day time period as means to reduce food-safety risks (Sharma et al. 2019; Litt et al. 2021).

BSAAO are often used in tandem with other agricultural management practices that suppress weeds. Data regarding the survival and persistence of bacterial zoonotic pathogens in soils and the ways in which these are affected by nutrient management continue to be produced, but less is known about the interaction with agricultural management practices for weed suppression. Use of plastic mulch during crop production along with poultry litter affected levels of E. coli in soil, whereby significantly (p<0.05) lower levels of E. coli were recovered from soil samples amended with poultry litter without plastic and from unamended plots compared to plots amended with poultry litter (Litt et al. 2021). E. coli populations declined faster in bare soil compared to soil with mulch and lettuce phyllosphere (Xu et al. 2016). This change was attributed to UV-radiation exposure in bare soil and lower levels of soil moisture. Higher soil moisture levels increase availability of free water, which subsequently enhances nutrient dispersion and free water available for use by microorganisms for chemical reactions. It has been suggested that mulching along with time of mulching alone and soil moisture can potentially change soil bacterial community composition and soil organic composition due to organic matter break down (Dong et al. 2017). Such biological events can promote growth of specific bacterial genera and change the abundance of soil microflora as well as bacterial pathogen growth and survival profile. These events could also influence E. coli survival durations in soils without plastic mulch.

Climatic conditions affect bacterial survival in soil and can be a source or pathway for contamination of produce in the pre-harvest environment. Due to heavy rain events, crops grown in close proximity to the soil could be exposed to pathogens if present in the soil, which may splash onto fruit surfaces or via direct contact with floodwater. Cumulative rainfall affected E. coli levels in soils amended with BSAAO without plastic, indicating that increased rainfall provided favorable conditions for bacterial growth

and proliferations (Litt et al. 2021), and regular rainfall during an analysis positively influenced growth of epiphytic bacterial populations (Xu et al. 2016).

Similarly, warming air and soil temperatures affected E. coli survival in unamended soil samples regardless of presence of plastic mulch (Xu et al. 2016), suggesting that warmer weather supports bacterial survival by providing optimum conditions for growth. Warmer soil temperature and reduced moisture loss by plastic mulch covering along with reduced exposure to excessive UV in sunlight can lead to enhanced bacterial survival, while in bare soil heat and UV irradiation from sunlight coupled with moisture loss could reduce bacterial survival in soil.

In some cases, plants grown in association with plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria have soils with improved water-holding capacity, altered soil matric structure, and changes in the effects on enteric pathogens (Markland et al. 2015; Zheng et al. 2018). For example, Bacillus subtilus UD 1022 has been shown to protect plants from colonization by human pathogenic bacteria like Salmonella and Listeria monocytogenes (Markland et al. 2015; Johnson et al. 2020). While pertinent pathogens like Salmonella sp. and shigatoxigenic E. coli may persist in agricultural soils, their presence and persistence are affected by soil amendment use and may be influenced by other agricultural practices.

As discussed in Chapter 4, another source of organic material applied to soils are biosolids, which are a product of wastewater treatment processes. Microbial pathogens (bacteria, viruses, protozoa, helminths, and fungi) in biosolids originate from human excreta. Composting with a validated time-temperature method can effectively inactivate most pathogens in biosolids and in biological soil amendments. Exposing these materials to high temperatures (e.g., 55°C) for prolonged times in static piles or aerated windrows is an effective means of pathogen reduction (Omar et al. 2023). As described with land application of BSAAO, regrowth or reactivation of bacteria can occur during incubation and storage of dewatered biosolids (Qi et al. 2007). Bacteria in land-applied biosolids will be affected by abiotic factors of the soil and competitive microflora in the soil. In many cases, the alkaline pH of some biosolids will reduce the risk of pathogen survival even more (Wei et al. 2010).

When it comes to foodborne pathogens and heavy metals, wastewater and biosolid production are highly regulated to prevent harmful effects on soil, crops, or animals. The regulations of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for the quality of biosolids originated in 1993, found in Title 40, Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) in Part 503 Biosolids Rule and includes requirements for use, disposal, and incineration.2 Biosolids’ standards focus on the presence of microbial pathogens, vector attractiveness, and presence of 10 inorganic metals.3 Microorganisms regulated by these standards include fecal coliforms, Salmonella spp., enteric viruses, and helminths. Biosolids can have variable pathogen loads. Cryptosporidium, Giardia, Salmonella, Listeria, Yersinia,

___________________

2 U.S. Government Publishing Office. “40 CFR Part 503—Standards for the Use or Disposal of Sewage Sludge.” Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. Accessed April 27, 2024. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-40/chapter-I/subchapter-O/part-503.

3 Arsenic, cadmium, copper, mercury, molybdenum, nickel, lead, chromium, selenium, and zinc.

and E. coli have been detected at variable levels (Flemming et al. 2017). A portion of the CFR describes pathogen reduction associated with use of biosolids, such as minimum times between land application and harvest of crops (Box 5-6).4 Biosolids contain several essential micronutrients for plants (e.g., copper, iron, manganese, molybdenum, and zinc) and can therefore be useful in application to micronutrient-deficient soils (Moral et al. 2002; Ozores-Hampton et al. 2011). Use of biosolids with crops may be restricted by the crop commodity and by more stringent restrictions set by the state or buyer.

Even when biosolids meet treatment requirements, pathogenic bacteria can survive these treatment processes and be transmitted to biosolid-amended soils (Badzmierowski and Evanylo 2019). Sagik and Sorber (1978) found that bacterial pathogens die more quickly in hot, dry conditions rather than moist, cold soils. Bacteria usually die off within a few weeks, viruses may persist for months, and protozoa and helminth life stages may survive for up to 10 years (Angle 1994). Microorganisms may leach through soil pores into groundwater (Gerba et al. 1975). Microorganisms have been shown to be transported most rapidly through coarse-textured soils and under saturated flow (Angle 1994).

BOX 5-6

Pathogen Reduction in Biosolids

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) categorizes biosolids into two classes of pathogen reduction: Class A and Class B. Class A biosolid may be applied to lawns, home gardens, or other types of land, or bagged for sale or land application and requires pathogen densities be reduced to below detection limits. These limits are set at less than three bacterial cells per four grams for Salmonella sp., less than one average detectable virus particle per four grams biosolids for enteric viruses, and less than one viable helminth ova per four grams biosolids (dry weight basis) for viable helminth ova (Boczek et al. 2023). Class B pathogen reduction is necessary for any other application and requires a fecal coliform density in the treated sewage sludge (biosolids) of 2 million colony-forming units per gram total solids (dry weight basis) and viable helminth ova are not necessarily reduced in Class B biosolids (Boczek et al. 2023). According to EPA, public access is not restricted for biosolids that meet Class A requirements. Class B sewage sludge still contains considerable pathogens; thus, site restrictions that limit crop harvesting, animal grazing, and public access are required.

SOURCE: Lu et al. (2012).

___________________

4 U.S. Government Publishing Office. “40 CFR Part 503—Standards for the Use or Disposal of Sewage Sludge, Subpart D—Pathogens and Vector Attraction Reduction.” Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. Accessed April 27, 2024. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-40/chapter-I/subchapter-O/part-503#subpart-D.

Beyond microbial pathogens, there is disagreement in the literature regarding the potential for health hazards in land-applied biosolids from other sources of contamination, which can result in contaminated food crops, drinking water contamination, and possible pollutant exposure via inhalation (Schowanek et al. 2004; Lindstrom et al. 2011; Sepulvado et al. 2011; Clarke and Cummins 2015; Lenka et al. 2021; Helmer et al. 2022). While many regulations govern production and application of biosolids, data gaps exist, including emerging chemical pollutants (pharmaceuticals and personal care products, microplastics, and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances [PFAS]) and potential contamination of soils, crops, and groundwater and surface water systems (see Chapter 6 for further discussion). The capacity of antibiotic-resistant genes (ARG) in land-applied biosolids to contribute to antibiotic resistance levels in the environment is also a topic of concern. Transmission of ARGs and antibiotic-resistant bacteria along with pathogenic bacteria have been discussed as potential global issues in applications of biosolids to crops (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards et al. 2021). Transmission of ARGs is not well understood. Several concerns exist, including the potential for ARGs to be concentrated during treatment processes (Munir et al. 2011), the persistence of genes at the application site, and the potential impact on public health (Pepper et al. 2018). Study of bacterial communities in amended soils and resistance genes is worthy of further exploration (Kang et al. 2022).

The microbial communities that live in land-applied biosolids are not well studied. Some microbial communities in fertilizers derived from biosolids have been identified to play active roles in soil enrichment (Hu et al. 2019; Pan et al. 2021), including proteobacteria and planctomycetes that are capable of nitrogen-fixation and ammonia oxidation (Kang et al. 2022).

Soil amendments of animal origin such as manure and biosolids generated from wastewater treatment processes can be effective sources of organic matter and of minimal risk for spreading human pathogens when properly treated and applied. Microbial pathogens may be introduced to the food supply when contaminated biological soil amendments reach the crops or carry run-off into water supplies. Regardless of the commodity or fertilizer type, good agricultural practices5 should be followed to reduce the risk of contamination (De et al. 2019).

Irrigation

Contaminated irrigation water has been associated with outbreaks of foodborne illness. Irrigation water can become contaminated through a variety of sources, including from cattle manure and poultry litter runoff that can contain harmful pathogens (Markland et al. 2017). The relative safety of irrigation water in terms of microbial food safety risks can be seen as a continuum, where surface water (rivers, streams, irrigation ditches, open canals, ponds, reservoirs, and lakes) has the most risks, followed by groundwater (collected from wells), and then municipal water has the lowest risk of microbial contamination.

___________________

5 See FDA (1998) for more guidance on good agricultural practices.

Groundwater is generally considered to be a low-risk source of water, but it can become contaminated (Anderson-Coughlin et al. 2021). In a review of enteric diseases attributed to groundwater (Murphy et al. 2017), more than 600 waterborne outbreaks globally were documented that occurred over a 65-year period caused by viral (norovirus and hepatitis A virus), bacterial (Shigella and Campylobacter), and protozoan (Giardia) pathogens. In the outbreaks for which the pathogenic agent could be confirmed or was suspected (n = 169 outbreaks), a variety of bacterial (46 percent), viral (40 percent), and protozoan (14 percent) agents were identified.

Mycotoxins

Soil health influences the vulnerability of plants to colonization of fungi that produce mycotoxins. Mycotoxins are toxic secondary metabolites produced by fungi that reside in soil. They can cause significant health issues and food losses (Box 5-7). Reduction of this food-safety problem in healthy soils is related both to the action of antagonistic soil microbes and fauna (Schrader et al. 2013) and to reduced plant vulnerability associated with reduced water and nutrient stress. Mycotoxins can be grouped into those that result from pre-harvest colonization and toxigenesis and those that primarily accumulate when the food is in storage (Zahra et al. 2019). This section will focus on those mycotoxins that occur in soil and that can accumulate in crops in the field.

BOX 5-7

Burden of Mycotoxins

Mycotoxins are pervasive food system contaminants that cause economic losses and burden public health worldwide (Ostry et al. 2017). They can cause carcinogenic, genotoxic, immunosuppressive, teratogenic, or mutagenic effects, but some can also cause acute toxicity and death if consumed in large quantities (Reddy et al. 2010; Gong et al. 2016; Omotayo et al. 2019). In high-income countries like the United States, regulatory structures protect the public from excessive exposure by ensuring that contaminated foods are detected, repurposed (e.g., for feed), or eliminated. These systems are reasonably effective but at significant expense. One study estimated that losses in U.S. corn, wheat, and peanuts averaged $932 million a year, while costs associated with regulatory processes, testing, and related measures were $466 million a year on average (Vardon et al. 2003). In lower-income countries, regulations may be in place but are likely to be weakly implemented because of the costs involved in effective food-safety monitoring and action. Consequently, mycotoxins exceed regulatory limits in an estimated 25 percent of the global food supply (Eskola et al. 2020).

There are hundreds of structurally diverse mycotoxins (Kabak et al. 2006), but the most agriculturally important mycotoxins are produced by fungi of the genera Aspergillus, Fusarium, Penicillium, Claviceps and Alternaria.6 The aflatoxins are the most toxic of the mycotoxins, and of this subset compounds, aflatoxin B1 is the most potent. It is the most carcinogenic naturally occurring compound known, and it causes hepatocellular carcinoma in humans and animals (Kew 2013). It is estimated that consumption of aflatoxin-contaminated food plays a role in 25,200–155,000 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma each year, that is, 4.6–28.2 percent of global cases (Liu and Wu 2010). There is evidence that it is also mutagenic and immunosuppressive (Gong et al. 2004; Zahra et al. 2023). Aflatoxins are produced by Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus. Agricultural soils are the main reservoir for Aspergillus inoculum. Spores of mycotoxigenic fungi like A. flavus can be transmitted from soil to plants or people by direct contact, movement of dust, splash droplets, or insect vectors (Horn and Dorner 1999; Abbas et al. 2009).

Water stress and high soil temperatures are important drivers of aflatoxin contamination (Horn and Dorner 1999; Jaime-Garcia and Cotty 2010). These environmental parameters may make plants more vulnerable to colonization by A. flavus, stimulate greater toxin production, and lead to greater incidence of aflatoxigenic strains of the fungus. Aflatoxin is a particular problem in hot, dry areas, and in cropping seasons affected by drought conditions where corn and peanut are grown, as these crops are especially vulnerable to aflatoxin accumulation (Yu et al. 2022). In the United States, aflatoxin commonly contaminates corn grown in the South and more rarely causes widespread losses in the northern states and Midwest. In drought years, like in 2012, however, mycotoxin levels on corn can be high across North America (Mueller et al. 2016). Peanuts, grown primarily in the Southeast, are particularly prone to pre-harvest aflatoxin contamination when temperatures are high during production and drought occurs late in the season (Butts et al. 2023). Once the fungi are established on the crop host, warm and wet conditions are favorable for pathogen growth and further toxigenesis (Cotty and Jaime-Garcia 2007).

Medina et al. (2017) analyzed the effects of various climate scenarios on the growth and toxigenesis of A. flavus, finding that fungal growth was similar across temperature, water, and CO2 regimes, while aflatoxin production was significantly increased during drought stress. Various studies on modeling of aflatoxin have reinforced the importance of water stress on aflatoxin accumulation in both corn and peanuts (Chauhan et al. 2015; Chalwe et al. 2019a,b). As drought risk increases with climate change, it is likely that aflatoxin will be an increasing risk for the food system. Modeling of future aflatoxin risk suggests that 90 percent of the corn-producing counties in 15 U.S. states will see increases in aflatoxin risk in the future, as the risk of conditions favoring aflatoxin accumulation in the field change with the climate and hot, dry summers become more frequent in northern areas (Yu et al. 2022). Modeling can be especially useful as a

___________________

6 Various mycotoxins are known or suspected to have a range of negative health consequences for people and animals; see Haque et al. (2020) for an overview of mycotoxins, the fungal species that produce them, and their pathological effects.

tool for bridging scientific disciplines and collaborative data sharing. Systems that coordinate this among multiple scientific disciplines, such as the USDA–Agricultural Research Service’s National Predictive Modeling Tool Initiative,7 can assist producers to make real-time management decisions to mitigate mycotoxin risk in the food and feed supply.