A Plan to Promote Defense Research at Minority-Serving Institutions (2024)

Chapter: 3 Outlining Opportunities at MSIs: An Assessment of the Capabilities of Minority-Serving Institutions

3

Outlining Opportunities at MSIs: An Assessment of the Capabilities of Minority-Serving Institutions

Minority-serving institutions (MSIs), including Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs), and Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs), offer a range of expertise and perspectives to the Department of Defense (DOD) and other agencies involved in defense-related research. Many currently are, or could be, positioned to fill key gaps in DOD research and to contribute to a diverse domestic science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) workforce. This chapter examines the capabilities of MSIs through the lens of the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education system; a mapping of MSIs’ Classification of Instructional Programs (CIP) against the DOD’s Critical Technology Areas (CTAs); and information from open information-gathering sessions, a commissioned paper, site visits to three institutions, and responses to a Request for Information (RFI).

MSI CAPABILITIES AND CHARACTERISTICS

More than two decades ago, the Educational Testing Service (ETS) issued a report that pointed to the underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic STEM students in higher education. Presciently, the report (Barton, 2002) looked at the nation’s demographic trends and national security needs to pose, “What does all of this portend for the adequacy of the pool of talent from which we can draw our scientists and engineers, and for increasing the representation of minorities in these professions?” The

ensuing years have borne out the relevancy of this question. By 2040, the United States will be majority-minority: that is, a majority of Americans will not be white. This is already true for Americans under the age of 18 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023). Although the ETS report was published in the early 2000s, it could have been addressed to the national security establishment today, which remains concerned with recruitment for the all-volunteer military and for talent qualified for classified national security work. Enhancing capacity at pertinent colleges and universities directly addresses the talent concerns for protection of the nation.

Approximately 800 MSIs across the country educate talent in fields pertaining to STEM, social sciences, and humanities in service to the domestic and international agenda of the United States. These fields include the modern languages, the social and behavioral sciences, the natural sciences, and engineering. All are essential to the mission of the DOD and other national security agencies. As detailed in previous National Academies’ reports, MSIs represent an underutilized and underappreciated asset in growing the STEM workforce (NASEM, 2019; see also Chapters 1 and 2). These institutions are essential to meeting the nation’s need for talent in STEM and other essential disciplines.

Some MSIs often serve underserved demographics such as nontraditional students, older students, veterans, and individuals who identify as disabled. For example, the average age of students at Tohono O’odham Community College was 33 years old in 2023 (Tohono O’odham Community College, 2023). At Iḷisaġvik College in Northern Alaska, 63 percent of students were older than 25 in 2023 (Iḷisaġvik College, 2023).

There is substantial diversity among MSIs related to mission, size, resources, location, STEM programs, and other characteristics. TCUs, for example, are generally very small institutions. Many have student enrollment in the low hundreds and staff in the dozens. Also, many TCUs are geographically remote, often more than 100 miles from an urban center. Sinte Gleska University on the Rosebud Indian Reservation, for example, is 168 miles from Rapid City and 224 miles from Sioux Falls, South Dakota. In a 2021 report, the Minority Business Development Agency characterizes these locations as “education deserts.”

The HBCUs include community colleges and baccalaureate institutions primarily focused on teaching and others with significant research activity. Research at these institutions is funded by a range of federal agencies. Primarily undergraduate institutions, such as Spelman College and Xavier University of Louisiana, support significant research activity

embedded within their instructional missions. Others, such as Clark Atlanta University and North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, also grant Ph.D.s in STEM and other disciplines. All these contribute to new knowledge and prepare needed talent.

Some state university MSIs embrace their roles serving minority students. For example, the University of Alaska has a formal Alaska Native success initiative that includes a goal to “recruit and hire Indigenous faculty and staff to have a workforce that reflects our Alaska Native population which is about 20 percent in the state” (University of Alaska System, 2024). Through existing STEM programs (including the Alaska Native Science and Engineering Program at the University of Alaska, Anchorage), paired with support programs specifically aimed at Alaska Native students, the university has documented STEM success, including an eightfold increase in the annual number of bachelor’s degrees in engineering awarded to Alaska Native or American Indian students from 2000 to 2016 (University of Alaska Anchorage, 2019). The university has documented that Alaska Native/American Indian students in these programs have an 8.2 percent higher retention rate and a 4.6 percent higher 5-year graduation rate than those Alaska Native/American Indian students not participating in supportive programs.

HSIs, as noted earlier, represent a growing, diverse proportion of the MSI landscape. Several are large institutions that have gained an MSI designation as Latinx populations in their region or state have increased. Significant disparities in research and development (R&D) funding, however, persist among HSIs.

According to Higher Education Research and Development (HERD) Survey data, the R&D expenditure rates of HSIs represent about 10 percent of all R&D expenditures annually (Table 3-1), but there is a large difference between the number of HSIs that are R1s and those that are not R1s.

Table 3-2 demonstrates the distribution of federal obligations for science and engineering (S&E) funding. Seventy-nine percent of all federally obligated S&E funding to High Hispanic Enrollment colleges and universities was awarded to 18 R1 institutions out of 185 listed HSIs. Only $735 million was awarded to the other 167 HSIs engaged in S&E research in FY2021.

TABLE 3-1 HSIs’ R&D Expenditures

| 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All R&D (million $) | 97,842 | 89,833 | 86,440 | 83,643 | 79,174 |

| All HSI R&D | 10,047 (10%) |

9,322 (10%) |

8,966 (10%) |

8,356 (10%) |

7,868 (9.94%) |

| Non-R1 HSI R&D | 834 (.85%) |

742 (.83%) |

748 (.87%) |

760 (.91%) |

706 (.89%) |

SOURCE: Committee-generated, based on National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics data.

TABLE 3-2 Federal Obligations for S&E Funding by Institution (FY2021)

| U. Illinois, Chicago | 299,000 |

| U. Texas, Austin | 270,453 |

| U. Arizona | 261,376 |

| U. California, Irvine | 258,585 |

| U. Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center | 210,727 |

| U. California, Santa Barbara | 185,654 |

| Arizona State U. | 184,688 |

| U. Texas Health Science Center, Houston | 161,199 |

| U. Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio | 138,088 |

| U. New Mexico | 133,471 |

| U. Central Florida | 121,234 |

| U. California, Riverside | 108,245 |

| U. Texas Medical Branch at Galveston | 102,749 |

| Texas A&M U., College Station | 90,553 |

| U. California, Santa Cruz | 75,189 |

| Florida International U. | 67,851 |

| Northern Arizona U. | 57,505 |

| U. Houston | 46,448 |

| All other HSIs (n=167) | 735 |

SOURCE: Committee-generated, based on National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics data.

CARNEGIE CLASSIFICATIONS AND THE EVOLVING DEFINITION OF “RESEARCH ACTIVE”

In 1973, the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education proposed a classification system to categorize degree-granting institutions in the United States (Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, 2024). Updated periodically since then, the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, according to its website, “is used in the study of higher education and [is] intended to be an objective, degree-based lens through which researchers can group and study similar institution.” Based on data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), inputs include numbers of undergraduates, extent of graduate program, and size of research portfolio. The six Carnegie Classifications range from “special focus institutions” (such as a music conservatory or religious institution) to “doctoral universities.” Doctoral universities can be classified with “very high research activity,” known as R1; “high research activity,” known as R2; and “doctoral/professional,” known as R3. According to the most recent classification (2021), 11 HSIs and no HBCUs were R1s; 12 HSIs and 11 HBCUs were R2s; and 15 HSIs and 16 HBCUs were R3s. Many of the HSIs with an R1 classification are large public universities with robust research funding in states with high Latinx populations (e.g., institutions in the Texas and California university systems). TCUs are not included in the Carnegie Classification system.

As the committee heard during open sessions, the next iteration of the Carnegie Classification, scheduled for release in early 2025, will have major changes in how the classification thresholds are determined (ACE, 2023). In addition, the Carnegie Classifications will incorporate the impact of institutions of higher education (IHEs) on social and economic mobility as part of assessing an institution’s impact and capabilities. One expectation is that at least one HBCU will be designated an R1, along with several additional HSIs, and a number of HBCUs and HSIs will be designated as R2s.

Although not an explicit intention of the system, an institution classified as an R1 receives significant prestige within and outside the academic ecosystem, being described as a top tier research university that can conduct the most cutting-edge research and provide high-quality instruction. Many universities dedicate considerable resources to reaching or maintaining R1 or R2 status. Part of the committee’s task was to address how MSIs can achieve R1 status. Many of the recommendations contained in this report can contribute to this goal for institutions that are on that pathway.

As a system for describing large, well-funded academic institutions, the Carnegie Classifications are well-situated to provide a cursory assessment of the research capabilities of R1 and R2 institutions. However, the Carnegie Classifications have fallen short in providing an assessment of the unique contributions that institutions that fall below the R1/R2 thresholds can provide the U.S. R&D ecosystem. R1s account for approximately 4 percent of all U.S. IHEs, which means that the vast majority of U.S. students pursuing undergraduate and postgraduate education do so at a non-R1 institution. Non-R1 institutions include a diversity of schools that serve rural communities, returning learners, Indigenous and African American communities, and other populations that have much to offer the DOD. Robust R&D engagement occurs at non-R1s. Thus, while R1 and R2 designation is important for many institutions, targeting resources to a broader array of MSIs will expand capacity and provide an opportunity to increase the diversity of perspectives engaging throughout the U.S. R&D landscape.

Findings:

- According to the most recent Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education (2021), 11 HSIs and no HBCUs were R1s; 12 HSIs and 11 HBCUs were R2s; and 15 HSIs and 16 HBCUs were R3s. TCUs are not included in the Carnegie Classification system, and many of the HSIs with an R1 classification are large public universities with robust research funding in states with high Latinx populations (e.g., institutions in the Texas and California university systems).

- Given reforms in the Carnegie Classification system, it is expected that at least one HBCU will be designated as an R1 institution, along with several additional HSIs, and a number of HBCUs and HSIs will be designated as R2s in 2025.

NATIONAL SECURITY NEEDS, DOD PRIORITIES, AND MSI CAPABILITIES

The DOD’s Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering has outlined 14 CTAs that will ensure that the nation maintains its competitive advantage globally and is prepared to address future research, development, and security needs. Institutions may find significant opportunities to engage in the full breadth of the Department’s R&D

ecosystem across basic and applied research infrastructure by mapping their existing S&E programs to these CTAs:

- Biotechnology

- Quantum Science

- Future Generation Wireless Technology

- Advanced Materials

- Trusted AI and Autonomy

- Integrated Network Systems-of-Systems

- Microelectronics

- Space Technology

- Renewable Energy Generation and Storage

- Advanced Computing and Software

- Human-Machine Interfaces

- Direct Energy

- Hypersonics

- Integrated Sensing and Cyber

To assess the current capabilities of MSIs to educate and engage in the DOD’s CTAs, the study committee reviewed the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) CIP codes.1 CIP codes provide insight into existing programs at IHEs and can allow organizations to identify institutions that are currently providing degrees in these fields. Looking across the CIPs, the committee agreed that five general fields of study in the CIP relate closely to the DOD’s CTAs.2 According to the committee’s analysis of NCES data, 89 percent of HBCUs have at least one program relevant to the DOD’s needs, and 62.5 percent of TCUs have existing programs relevant to the CTAs. Mapping CIP codes with CTAs, however, requires additional inputs to fully assess the current and existing capabilities of MSIs, such as setting thresholds for the number of programs that exist at MSIs currently and identifying the level of resources applied to relevant DOD programs

___________________

1 See Classification of Instructional Programs Codes, https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/cipcode/resources.aspx?y=56.

2 The specific CIP codes analyzed were Engineering (60); Engineering/Engineering-related Technologies/Technicians (77); Physical Sciences (45); Biological and Physical Sciences, Physical Sciences, General, Social Sciences (40); Social Sciences, General, Computer Science, Linguistics and Computer Science, Mathematics and Computer Science, Biochemical Engineering, Chemical Engineering, Chemical Engineering Technology/Technician, Chemical Engineering, Other.

to highlight opportunities for increased support that can facilitate access to skill development for students across MSIs.

Findings:

- More than 800 MSIs across the country educate talent in STEM, social sciences, and humanities and may serve the U.S. domestic and international agenda for defense and national security.

- Targeting resources to a broader array of MSIs will expand capacity and provide an opportunity to increase the diversity of perspectives being engaged throughout the U.S. R&D landscape.

- According to the committee’s analysis, 89 percent of HBCUs have at least one program relevant to the DOD’s needs, and 62.5 percent of TCUs have existing programs relevant to the DOD’s CTAs.

ADDITIONAL INPUTS ON MSI CAPABILITIES AND OPPORTUNITIES

The committee commissioned a paper from an independent researcher (Zhang, 2024) to characterize the current research capacity of MSIs and explore potential avenues of investment. To review institutional R&D activity, the author drew from two datasets from the National Science Foundation (NSF): the HERD Survey and the Survey of Science and Engineering Research Facilities. The HERD Survey, conducted annually, collects information on R&D expenditures at U.S. colleges and universities broken down by field and expenditure type. The S&E Research Facilities survey, conducted biennially, collects information on the amount of space and costs for R&D facilities, also broken down by field. The HERD and Facilities surveys collect data on all U.S. academic institutions reporting at least $150,000 (National Science Foundation, 2022a) and $1 million (National Science Foundation, 2022b) in R&D expenditures in the previous fiscal year, respectively. Thus, not all MSIs are included in these NSF data.

The commissioned paper also analyzed the data through a geographic lens. Previous National Academies’ reports have recommended the development of meaningful partnerships between MSIs and other institutions, particularly R1s (stressing that these should be mutually beneficial and not check-the-box arrangements by the larger institutions by providing an equal exchange in research attribution, funding, personnel, and resources). While the data and analysis required to match institutions were beyond the scope of the report, the paper presented preliminary findings from available

IPEDS data to show that most MSIs are not close to an R1 or R2 university. Disregarding own-institution status, HBCUs have a median distance of 30 miles to an R1 and 50 miles to an R2 (see Table 3-3). The median distance between a TCU and an R1 is 174 miles. Around 30 percent of HBCUs have an R1 within 5 miles, while only 12 percent of HSIs have an R1 within 5 miles. There is only one TCU with an R1 located within 5 miles.

There are no outcomes data to empirically verify if co-location with an R1 or R2 augments research output for MSIs. While fruitful partnerships can develop across the miles (e.g., the Princeton-HBCU alliance presented at one of the Town Halls), a reasonable assumption is that proximity facilitates collaboration. Future studies could incorporate collaborative research outputs or faculty/student mobility data to directly measure the impacts of geographical proximity between MSIs and R1/R2 institutions on research capacity. Another aspect to examine is proximity of MSIs to federally funded R&D centers, military installations, and other facilities (see also Chapter 4). As an example, at a Town Hall, a presenter described how Fayetteville State University, although located in a rural area, takes advantage of its location near Fort Liberty (formerly Fort Bragg), one of the largest military bases in the nation.

The paper also looked at three general areas of research capacity delineated by the amount of investments required (e.g., labs, instrumentation, high-performance computing) to make the following observations related to MSI research potential:

TABLE 3-3 Summary Statistics of MSI Distance to R1 and R2 Universities

| Measures | HBCU | HSI | TCU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Miles to Closest R1 | 30 (115) |

42 (362) |

174 (319) |

| Institutions with an R1 within 5 Miles | 28 | 40 | 1 |

| Institutions with an R1 within 10 Miles | 39 | 81 | 1 |

| Median Miles to Closest R2 | 50 (116) |

57 (364) |

187 (117) |

| Institutions with an R2 within 5 Miles | 14 | 38 | 1 |

| Institutions with an R2 within 10 Miles | 18 | 71 | 1 |

| Total | 100 | 331 | 35 |

SOURCE: Zhang, 2024.

- Investment-Heavy Fields: Life sciences require intense investment in R&D funding, equipment, and facility space. Engineering and physical sciences also require significant investment in these areas. These investment requirements have proven and will continue to prove difficult for many MSIs to compete with R1s. A possible avenue for growth is strategic partnerships between MSIs and R1s for fields that require large capital investments.

- Investment-Light Fields: Math and statistics, psychology, and social sciences require much less investment in R&D funding, equipment, and facility space. This may be an area for MSIs to grow their research capacity.

- Fields on the Rise: Computer science is on the rise for R1 spending, especially in equipment and facility space. This is not surprising given the increasing importance of computer science in the past two decades on topics such as cybersecurity and the protection of data. Geosciences and agricultural sciences also show much less differential between R1 and MSI spending.

Institutional objectives are a critical driver for funding decisions. The top 10 HBCUs in terms of R&D spending and facility space tend to be more specialized than the top 10 HSIs in these areas, which may call for different strategies of increasing research investment. Among HSIs, there are more than 300 institutions with a much more heterogeneous distribution than the 11 HSI R1s. MSIs also have a community-driven mission, and it is thus important to determine to what extent expanding research capacity across all fields versus specializing in a few fields is the goal. Additionally, assessing the role to which novel strategies, such as investing in local industries and community partners, can support increased engagement of MSIs may provide unique opportunities for the DOD and institutions with more community-driven missions.

Findings:

- HBCUs have a median distance of 30 miles to an R1 and 50 miles to an R2. The median distance between a TCU and an R1 is 174 miles. Around 30 percent of HBCUs have an R1 within 5 miles, while only 12 percent of HSIs have an R1 within 5 miles. There is only one TCU with an R1 located within 5 miles. While there are no current studies on the relationship of research capacity to proximity, investigating the potential relationships between

- neighboring institutions may identify strategies to increase the engagement of MSIs in R&D.

- The top 10 HBCUs in terms of R&D spending and facility space tend to be more specialized than the top 10 HSIs in these areas, which may call for different strategies to increase research investment. Among HSIs, there are more than 300 institutions with a much more heterogeneous distribution than the 11 HSIs that have R1 status.

Town Halls and Site Visits

Two series of public sessions informed the committee, as noted in Chapter 1. In late 2023, the committee held three open sessions to learn about the DOD, other federal, and nonprofit models of engagement with MSIs that might be applied elsewhere (see Appendix A for the agendas and Chapter 4 for highlights).

As a related but discrete effort to this consensus study, the DOD previously supported a series of Town Halls (highlighted below and in NASEM, 2024). Their goal was to further explore key questions that emerged from the 2022 report and to build on its recommendations related to “building research capacity” and developing “true partnerships” between MSIs, other IHEs, and federal agencies. They were held in Washington, DC; Albuquerque, NM; and Chicago, IL. The committee examined the proceedings of those Town Halls.

In addition, subsets of the committee made site visits to Fayetteville State University, Diné College, and California State University at Bakersfield.

Themes that resonated across the committee briefings, Town Halls, and site visits included the following:

- The need for a long-term view: Capacity building and partnership development take time and need sustained resources and patience. Several presenters stressed that research infrastructure should be built over time, with adequate resources for maintenance and training. Similarly, partnerships are created and nurtured over time. A number of MSI representatives shared their frustration when R1s and other larger organizations contact them for a quick sign-off for a partnership that exists in name only.

- Value of consortia: Consortia facilitate access to education, publications, conferences, and networking, which particularly helps early career researchers. Examples included the South Big Data Innovation Hub, Applied Research Initiative for Mathematics and Computational Sciences, and the HBCU Science and Technology Council. Nonprofits and philanthropic organizations can serve as convenors of these consortia.

- Considerations of smaller institutions: Presenters from smaller institutions shared their frustration when agencies are reluctant to provide infrastructure support because it will serve a smaller number of students and faculty. Equipment is essential in running many programs, and excluding these institutions also marginalizes potential STEM talent. Several presenters from smaller institutions appreciated the mentorship provided by larger, more well-resourced schools, but they also stressed the value of peer-to-peer information exchange. In addition, several described situations in which their students and faculty were involved in partnerships with larger institutions, only to have them recruited away to these larger places.

- Institutional constraints: Heavy teaching loads were often cited as an obstacle to growing research capacity. Faculty need time to connect with the DOD and other partners, attend conferences, and be proactive in scouting research opportunities, something that is difficult to do while teaching as many as four or five courses a semester. Several presenters noted that their institutions do not have a Ph.D. cohort—the California system that distinguishes between research and teaching-focused institutions was brought up by several presenters. Suggested work-arounds included using postdocs, lab managers, undergraduates, and community college students and leveraging novel opportunities to engage with funders such as participating in virtual meetings with program staff.

- Administrative capacity: A common obstacle is the lack of research infrastructure, including staff who are trained to manage federal grants and contracts and capitalize on commercialization and intellectual opportunities. Several participants from

- state-funded institutions saw funding decrease in recent years. Less-resourced institutions do not have the same level of support as better-resourced institutions, putting them at a further disadvantage.

- Regional focus: Several presenters explained that their students are primarily from the local regions and want to remain there for their careers. The DOD and other defense-related facilities in these areas can take advantage of this preference by forging meaningful relationships with students early in their academic pathways.

RECOMMENDATION 3-1: For MSIs to contribute more fully to defense-related research, research capacity and talent must be developed and strengthened. This is a unique strategic opportunity for the DOD and national security. Many MSIs (in particular TCUs) embody distinctive perspectives and so have the potential to make completely unique research contributions in areas such as addressing agricultural systems that are resilient in drought conditions. These distinctive ways of thinking, problem-solving, and social organization should be of interest to both the DOD and the broader scientific community. Investing in investigators at non-R1 MSIs will not only increase the defense-related research capacity base nationally, but also deepen and diversify the available investigators that can support and advance the Department’s R&D needs.

- To partially engage this opportunity, the DOD, with support from Congress, should develop and administer a DOD MSI Investigator Award for very capable scholars at HBCUs, TCUs, and MSIs. This new program should be modeled after existing department programs such as the DARPA Young Faculty Award, Air Force Young Investigator Program, and ONR Young Investigator Program. In the implementation of DOD MSI Investigator awards, the following factors should be included:

- Up to 100 awards made per year across the Department’s branches (Air Force, Navy, Army, etc.).

- Tracking of the number of awards made to each institution type to guide evaluation, outreach, and programmatic planning.

- An average of $150,000 per grant per year over a 5-year grant period with the option to renew. This sustained funding will include funding that enables each DOD MSI Investigator

- to establish a research lab at their institution, pursue topics relevant to the DOD’s R&D needs, and serve as a focal point for increased engagement for defense-related research.

- Cohorts of investigators should be convened in-person on an annual basis to discuss successes, roadblocks, and recommendations to refine and reshape this program based on the unique and not-well-understood challenges and opportunities at their sites with the identification appropriate metrics for evaluation.

- The focus should be on faculty at HBCUs, TCUs, and non-R1 MSIs with award recipients providing 51 percent of their effort to the funded research project during the duration of the award. The National Institutes of Health PIONEER award and Howard Hughes Medical Institute Program may serve as models for an agency-wide program that supports promising scientists across career stages in addressing high-risk/high-reward issues relevant to the DOD’s mission.

- The DOD should avoid the use of ‘tenure track” designated faculty as a criterion. The use of “tenure track” appointments creates a barrier for engagement for smaller institutions such as TCUs. As a result, any program focused on developing researchers at non-R1 MSIs that use “tenure track” as an eligibility criterion would preclude both their engagement from these institutions and the DOD from broadening its potential researcher base.

- Review criteria and processes should be developed with an advisory council that includes researchers and research administrators from MSIs and institutions with historical engagement with the DOD.

RECOMMENDATION 3-2: To support the existing missions of MSIs to educate and provide support for investigator release time, the DOD should develop a postdoctoral fellowship program for MSIs geared toward doctoral recipients with specialized expertise in defense-related research areas, broad disciplinary understanding, and interest in developing instructional skills. Funding that provides relief for course and research support at MSIs will help incentivize institutions where teaching loads prohibit significant engagement in research. It can also help support the careers of postdocs pursuing experience as faculty. The DOD should incorporate the following into the program:

- Recipients can allot 50 percent of their time as a research associate within the lab of a faculty member conducting defense-related research and 50 percent of their time to teach courses typically covered by the investigator.

- The duration of the fellowship should correspond with the length of a typical research grant to ensure continuity in course coverage. It should be affixed to non-R1 primary teaching institutions and DOD-relevant MSI funding mechanisms.

- A matching mechanism that connects prospective fellows with MSI faculty should facilitate awarded fellows’ identification of a supervising investigator.

- A postdoctoral mentoring plan should be included. Mentoring plans should be standardized to ensure continuity in support for fellows, and mentors should receive training on mentorship.

Responses from the RFI

As part of this study, the committee issued an RFI to better understand institutions’ research ecosystems. The survey received more than 50 responses. While not a statistically rigorous sample, the responses provide an illuminating snapshot of how institutions see themselves, and administering similar information requests periodically may assist in providing a more comprehensive view of MSI research ecosystems. Respondents encompassed broad coverage of Carnegie Classifications as well as significant diversity related to location and size of the student body, from several hundred to more than 50,000 students. Each has a significant percentage of faculty involved in at least one, and usually all or most, of the six CIP areas mentioned above.

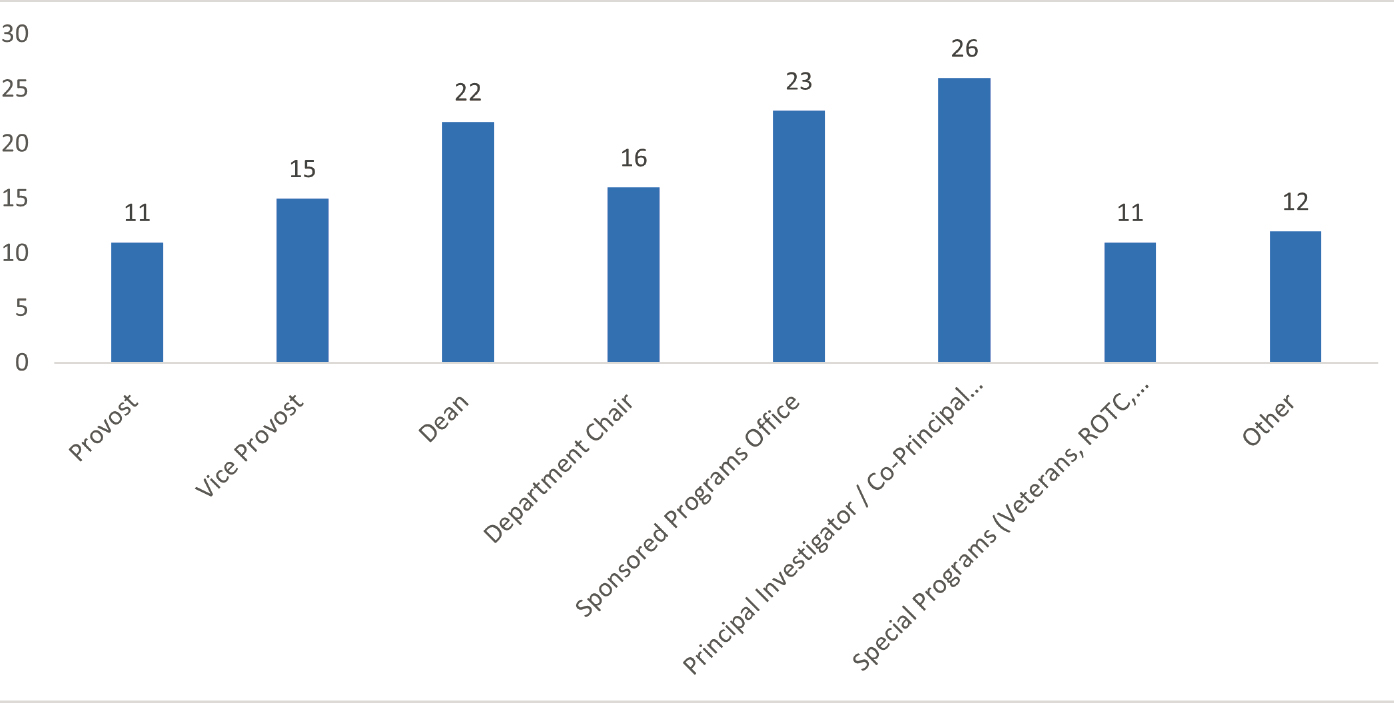

While all respondents indicated they have research within their strategic plan, the extent to which the institution conducted research with DOD support varied greatly. A variety of different roles currently engage with the DOD, including vice presidents of research through sponsored program offices, administrators, department chairs, principal investigators, and others (Figure 3-1).3

___________________

3 The committee referred to the definition “principal investigator” in 2 CFR § 1108.295 – “The single individual whom an organization that is carrying out a research project with DOD support designates as having an appropriate level of authority and responsibility for leading and directing the research intellectually and logistically, which includes the proper conduct of the research, the appropriate use of funds, and compliance with administrative requirements such as the submission of performance reports to the DOD.”

SOURCE: Committee-generated RFI.

Points of particular relevance to this study from RFI responses include the following:

- Prioritization of research: While 100 percent of respondents indicated that research is part of their institution’s strategic plan, approximately one-third of respondents also indicated that research is not a high priority. This highlights the need to incentivize structures that support institutional engagement in research for the DOD to leverage significant unique capabilities available at these institutions.

- Ability to conduct classified research: Close to 80 percent of respondents indicated having access to classified infrastructure, either directly in-house or through established partnership agreements. This potentially indicates that lack of access to secure infrastructure is not an obstacle in engaging in DOD research. Other areas of investment/development—such as unclassified research infrastructure and specialized administrative, leadership, and management processes necessary for DOD research—are likely to lead to higher engagement.

- Coordination of DOD strategy: Connections to the DOD span multiple roles at an institution (provosts, vice presidents, etc.), but connections with individual principal investigators appear to be the most common. This data point, together with how institutions coordinate their research strategy, indicates that there may be a significant benefit from coordinating a DOD research strategy at multiple levels within institutions, including faculty leadership development programs specifically focused on DOD engagement such as the Tougaloo College Research and Development Foundation. Together with apparent access to classified infrastructure, such coordination has the potential to create a transition pathway from basic to applied research by leveraging currently untapped capabilities.

Several open-ended comments from respondents indicate opportunities for the DOD. One respondent noted, “Our institution has productive collaboration with DOD, and we are prepared to do more.” Several noted their capabilities in such cutting-edge domains as directed energy,

cybersecurity, and advanced materials. Suggestions included assigning DOD subject matter experts to MSIs full-time or on a rotational basis. The Army Research Laboratory Open Campus program could serve as a framework. This could jumpstart the needed external support and expertise to help faculty align their research more efficiently with DOD mandates and mission sets. Another cautioned, “Administrative and human capital systems are not adequate to support serious research in many instances” and pointed to the lack of defined professional development among staff and faculty to pursue in-depth research. One respondent suggested that the DOD include research professors as partners, which in turn supports students in the STEM workforce pipeline.

RECOMMENDATION 3-3: Inter-institutional collaborations among MSIs are an underutilized strategy to leverage unique perspectives, skills, and abilities to further the DOD research objectives. Frequently, no single institution possesses the necessary breadth of talent to broadly serve the DOD’s research needs. Furthermore, under-resourced administrative staff often disincentivize MSI collaborations, especially when a well-resourced Primarily White Institutions R1 is poised to take the lead. To increase capacity development and engagement, the DOD should develop a funding program to support the creation of research consortia with an HBCU, TCU, HSI or other non-R1 MSI lead. The research consortia would focus on a clear area or project and include scholars from three or more MSIs. The committee is aware of the Research Institute for Tactical Autonomy, led by Howard University, an HBCU, and recommends that additional consortia be developed to address research projects of critical need to the DOD to facilitate the engagement of more MSIs. In the implementation of this funding program, the following factors should be included:

- Support for developing consortia that fund R&D.

- Funding for at least 5 years for each consortium to support planning, execution, and evaluation activities.

- Support for consortia that exhibit intentional and equitable collaboration and mutually beneficial partnerships through strategies, including at least 6 months of pre-award communication, partnership agreements, and/or articulated resource and personnel sharing frameworks.

- Planning grants for prospective consortia to develop full proposals.

- Supplements for institutional mentorship between MSIs and known performers to assist with the consortia’s planning and implementation.

RECOMMENDATION 3-4: An under-resourced administrative infrastructure to secure, manage, and coordinate grants, contracts, and other opportunities is a significant barrier to engagement in the DOD and other federal agency opportunities. To increase the ability of under-resourced MSIs to adequately and effectively participate in opportunities, the DOD, with congressional support, should develop a funding program to develop administrative hubs. The administrative hubs would allow MSIs the option to coordinate through a professional organization that possesses the administrative expertise and resources necessary to support grant and contract acquisition and management (pre- and post-award). The hubs could also coordinate faculty and student participation in DOD opportunities, and communicate the current and evolving capabilities of member institutions. Additionally, these hubs would be used by three or more non-R1 MSIs that are regionally located or geographically close to facilitate coordination and mutual use and complications due to differences in administrative policies, complexities and protocols need to be built into use agreements. In the implementation of this program, the following factors should be included:

- Funding for at least 5 years to launch each hub and facilitate planning, execution, and evaluation.

-

Support for lead organizations with clearly articulated missions relevant to MSIs who exhibit intentional development through strategies, such as the following:

- Referencing at least 6 months of pre-award communication,

- Partnership agreements with participating institutions,

- An administrative capability track record, and

- Clearly defined sustainability plans that demonstrate maintenance and long-term administrative support for participating institutions post-award.

- Planning grants for prospective hubs to develop full proposals.

REFERENCES

ACE (American Council on Education). 2023. Carnegie Classifications to make major changes in how colleges are grouped and recognized. https://www.acenet.edu/News-Room/Pages/Carnegie-Classifications-to-Make-Major-Changes.aspx.

Barton, P. 2002. Meeting the need for scientists, engineers, and an educated citizenry in a technological society. https://www.ets.org/research/policy_research_reports/publications/report/2002/cjuq.html.

Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. 2024. About Carnegie Classification. https://carnegieclassifications.acenet.edu/.

Iḷisaġvik College. 2023. Annual report: Cooperation. https://indd.adobe.com/view/f9cb81fa-a634-49ee-9799-490984ad801b.

Minority Business Development Agency. 2021. Tribal colleges and universities, reservation entrepreneurship and business development. Minority Business Development Agency. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.mbda.gov/tribal-colleges-and-universities-reservation-entrepreneurship-and-business-development.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2019. Minority-serving institutions: America’s underutilized resource for strengthening the STEM workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25257.

NASEM. 2024. Building defense research capacity at historically black colleges and universities, tribal colleges and universities, and minority-serving institutions: Proceedings of three town halls. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/27511.

National Science Foundation. 2022a. Higher education research and development (HERD) survey 2021. National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. https://ncses.nsf.gov/surveys/higher-education-research-development/2021#methodology.

National Science Foundation. 2022b. Survey of science and engineering research facilities 2021. National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. https://ncses.nsf.gov/surveys/science-engineering-research-facilities/2021#methodology.

Tohono O’odham Community College. 2023. Annual report. https://tocc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Final-for-Web-TOCC-AnRept2023-as-of-2.5.2024.pdf.

University of Alaska Anchorage. 2019. UAA ANSEP graduation study: UAA bachelor of science degrees awarded in engineering and other STEM majors comparisons (AY2000-2007 and AY2011-2018, by race and ethnicity). https://cdn.ansep.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/2019-UAA-ANSEP-Graduation-Study-04MAY19.pdf.

University of Alaska System. 2024. Alaska Native success initiative. Office of Race, Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, Success. https://www.alaska.edu/redis/ansi/.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. 2023 population projections for the nation by age, sex, race, Hispanic origin, and nativity. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2023/population-projections.html.

Zhang, R. 2024. Building up research capacity at minority institutions: Report for the National Academy of Sciences. Commissioned paper for the National Academies’ Committee on the Development of a Plan to Promote Defense Research at Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Tribal Colleges and Universities, and Hispanic-Serving Institutions. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/27838.