A Plan to Promote Defense Research at Minority-Serving Institutions (2024)

Chapter: 4 Department of Defense and Other Federal Support for Research and Development

4

Department of Defense and Other Federal Support for Research and Development

The federal government’s investment in research and development (R&D) supports strengthening the nation’s competitiveness and security. As noted in Chapter 1, this report focuses on defense-related research at the Department of Defense (DOD) as well as research supported by other agencies in service of the national security of the United States. This and other studies (e.g., NASEM, 2019, 2022) point to the competitive advantages of increasing the capacity of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs), Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs), and other minority-serving institutions (MSIs) to conduct defense-related research and train the next generation of scientists. Among the benefits to national and economic security are increases to the talent pool of U.S. citizens equipped to take on this work and to offer complementary areas of knowledge, innovation, and experience to the existing R&D ecosystem.

This chapter looks more closely at current and potential opportunities, primarily within the DOD but also at other agencies that perform defense-related research. In addition, the committee notes that while most defense-related research has focused on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), the social sciences, humanities, and other disciplines have been shown to be important in addressing emerging mission needs that range from rapid adoption of autonomy to tackling the integrity of the information environment (NASEM, 2020). Moreover, some emerging national challenges, such as those related to environmental and societal impacts of new technologies, fall into the specific and unique

expertise of many MSIs that have not traditionally engaged with the DOD. This recognition further calls for an acceleration of MSI participation in defense-related research.

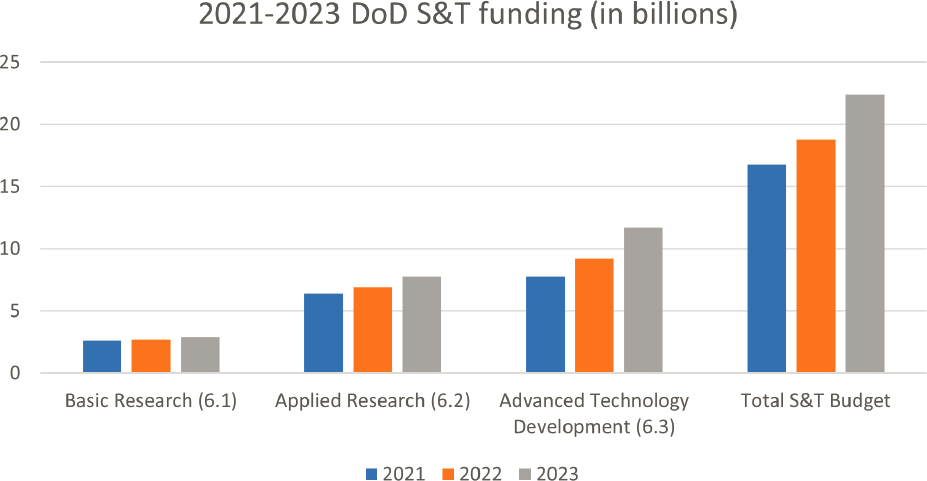

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

The DOD supports a well-defined pipeline of eight technology readiness levels mapped to contractual vehicles ranging from Basic Research (Budget Activity Code 6.1) to Software and Digital Technology Pipeline Programs (Budget Activity Code 6.8). Understanding the technology readiness levels and their impact on budgetary decision-making illustrates the existing national defense-related research infrastructure that can be leveraged for increased MSI engagement. In FY 2023, Congress appropriated $144 billion to this pipeline as a whole, known collectively as research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E). Within RDT&E, university science and technology (S&T) engagement typically occurs in the 6.1 through 6.3 parts of the pipeline: Basic Research (6.1), Applied Research (6.2), and, to a lesser extent, Advanced Technology Development (6.3). The FY 2023 budget for these three areas of research was $22.48 billion (DOD, 2023, 2024a), which represents a small increase over the past few years (Figure 4-1). Multiple entities within the DOD manage these funds. They include the Departments of the Air Force, Army, and Navy; offices within the Office of the Secretary of Defense; and defense agencies such as the Defense Advanced

SOURCES: DOD, 2023, 2024a.

Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA). (See NASEM, 2022, for further information.)

As discussed in greater detail below, despite the DOD efforts to explain and streamline the process, participants from institutions of all sizes shared with the committee their difficulty in navigating the system, given its scope and complexity. Universities that work successfully with the DOD must develop a unique set of administrative, infrastructure, and process capabilities, along with general awareness of mission needs. Even universities that have a record of funded research with other agencies such as the National Science Foundation (NSF) often require a different set of resources to engage at scale with the DOD. Working on the DOD research requires research infrastructure, different financial processes (e.g., related to contract rather than grant management), and, in some cases, specialized facilities.

The DOD has identified a pressing need to broaden its performer base given the scope of relevant challenges to be addressed, many of which require interdisciplinary expertise. Many national security challenges identified in guiding documents of the Department ranging from emerging technologies and how adversaries use them, to space exploration, to mitigating effects of climate change on national security, to supply chain resilience, to rapid adoption of artificial intelligence require bringing together the most diverse set of expertise possible. Making sure that the DOD is leveraging the unique research capabilities of MSIs, including HBCUs, TCUs, and HSIs, is vital to addressing those challenges. Social science research may offer a means of rapidly including HBCUs, TCUs, HSIs, and other MSIs in the DOD research portfolio (NASEM, 2020). Thus, the DOD could pursue initiatives that strengthen capacity for research across a broader performer base in areas of need for national security (e.g., STEM, social sciences, medicine, and related studies).

RECOMMENDATION 4-1: Engaging the breadth of research disciplines relevant to national security is necessary to fully explore opportunities and increase MSIs’ engagement in defense-related R&D. Congress should create programs that increase the utilization of the full breadth of the DOD’s research in non-engineering disciplines.

- The DOD should further develop its research capacity by including and expanding funding to support the social sciences in its calls for proposals, focusing on the unique perspective MSIs bring to these fields. HBCUs, TCUs, and MSIs can provide rich contributions in the social sciences and other

- non-engineering-focused disciplines that are critical to DOD research.

Targeted Programs

Agency Perspectives

Within the DOD, the three military services, DARPA, DTRA, and other entities have programs that are either explicitly designed for MSIs or are particularly conducive to MSI participation. In addition, the locus for MSI engagement within the DOD is the Research and Education Program for Historically Black Colleges & Universities and Minority Institutions (MIs) within the Office of the Secretary of Defense. The office also serves as the DOD liaison to White House initiatives to promote educational equity, excellence, and economic opportunity.1 While the office has made strong contributions, its budget of about $100 million represents only 0.56 percent of the S&T budget.

The committee heard presentations at its open sessions and reviewed materials to learn about DOD programs and goals related to engaging MSIs. A common thread was that MSIs are, and can become further, involved in DOD-funded research in priority areas, including in the 14 identified Critical Technology Areas or CTAs (see Chapter 3). The speakers detailed efforts to support research, faculty development, student training (from K-12 outreach through undergraduate to graduate/postdoc support), and infrastructure investment. The open sessions in November and December 2023 also provided a way for the committee to engage with the DOD and other organizations about where they see the opportunities and challenges for greater MSI involvement in defense-related research.

For example, the Navy’s HBCU/MI program director stressed the value of personal engagement. Although he clarified that the program works carefully to ensure that prior history with the program does not influence funding decisions, he pointed out that (1) an important measure of success is engagement and number of connection points; (2) relevance to the DOD mission need is a key attribute of engaged institutions; (3)

___________________

1 These include White House initiatives targeted to Black Americans (https://sites.ed.gov/whblackinitiative/); Hispanic Americans (https://sites.ed.gov/hispanic-initiative/); Native Americans (https://sites.ed.gov/whiaiane/); and Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander communities (https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/WHIAANHPI-2023-Report-to-the-President-FINAL.pdf).

in-person engagements are critical to success, but resource limitations make those engagements difficult to scale; and (4) regular engagement leads to more productive, mutually beneficial relationships and addressing of DOD mission needs.

The Director of Social Sciences for the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering discussed the Minerva Research Initiative.2 He observed that while interdisciplinary social science research and collaborations are encouraged, the office does not have specific programs focused on HBCUs, TCUs, or other MSIs. Possible development of such programs could be beneficial to the DOD and leverage advanced research capabilities available at those institutions.

The Air Force Office of Scientific Research program manager for HBCUs and MSIs highlighted the need for capacity building along with supporting faculty and researcher pathways through engagements with the DOD. The Air Force representatives highlighted programs ranging from grants to Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer in support of small businesses.

The technical engagement program manager at DTRA highlighted the importance of understanding broad research capabilities across HBCUs and MSIs. His focus was on workforce development and opportunities for engaging with DTRA-relevant programs in chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear threats.

A representative from DARPA discussed several opportunities, including DARPAConnect, which is focused on broadening institutional participation in DARPA programs. DARPA also has engagement, outreach, and education programs focused on institutions that may not have had previous engagement with the agency.

Overall, these presentations highlighted the following:

- The need for a better understanding of key institutional research strengths for MSIs that do not typically engage with the DOD.

- The importance of addressing DOD’s mission needs in research and engineering with a broad a set of capabilities available nationally.

- The critical role of in-person engagement and barriers to scaling that approach.

___________________

2 For more information on the Minerva Research Initiative, see https://minerva.defense.gov/.

- The challenge of building and sustaining research infrastructure and the management of teaching loads at HBCUs, TCUs, HSIs, and other MSIs.

Examples of Programs for MSIs

Through presentations at the open sessions, the 2023 Town Halls (NASEM, 2024), and their own experience, committee members reviewed a variety of programs targeted at MSIs. The information below is not meant to be exhaustive but instead offers examples of initiatives related to research, faculty, student, and infrastructure support, some of which could be expanded or replicated in other parts of the Department.

Research Grants: In FY 2023, the HBCU/MI program funded 82 researchers for 4-year grants totaling $61.7 million. A supplemental program sponsored by the Office of Naval Research (ONR) funded an additional $27 million to HBCUs to conduct research in relevant CTAs.3 The U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Army Research Laboratory (ARL) administers the Research and Education Program for HBCUs/MIs on behalf of the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, with collaboration opportunities available to broader academia as well as opportunities targeted to HBCUs/MIs.4 The Department of the Navy’s HBCU/MI program supports the participation of underrepresented institutions in navy-relevant RDT&E programs and activities. In addition to core basic and applied research programs executed by ONR program officers and research performed at naval laboratories, ONR sponsors research programs performed by academic research institutions, including the Defense University Research Instrumentation Program (DURIP).

Faculty Support: The DOD HBCU/MI Faculty Fellowship Program aims to strengthen the collaboration between the DOD and STEM faculty affiliated with HBCUs and other MSIs.5 Other opportunities for faculty under

___________________

3 For more information, see https://dodhbcumiopportunities.com/. For the ONR Supplemental Awards, see https://www.cto.mil/27mil-investment-hbcu/.

4 For more information on general opportunities, see https://arl.devcom.army.mil/collaborate-with-us/audience/academia/. For opportunities for HBCUs/MIs, see https://arl.devcom.army.mil/collaborate-with-us/audience/hbcu-mi/.

5 For more information, see https://orau.org/usre/.

the Office of Basic Research include the Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship; Minerva Research Initiative in collaboration with the U.S. Institute of Peace; and the Academic Research Security initiatives with more than 130 opportunities including development, fellowships, and internships.6 Young Investigator programs are also administered by the Navy, Air Force, and DARPA; these are not targeted to MSIs or minority investigators at non-MSIs.7

Student Support: The DOD HBCU/MI Summer Research Internship Program aims to increase the number of minority scientists and engineers throughout the DOD.8 The DOD maintains an overarching program called DOD STEM, which highlights collaboration between the DOD (including all branches/other federal agencies) and those involved in STEM K-12, undergraduate/graduate, and early career programs across the country. It offers a database of current STEM program, internship, and scholarship opportunities across the country.9 The Science, Mathematics, and Research for Transformation (SMART) program offers scholarships and stipends to students, who then commit to working with the DOD as civilian employees.10

Infrastructure Support: The Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering provides technical assistance workshops as part of a series of training and educational activities intended to provide program, process, and funding opportunities and information to MSIs. The workshops focus on both DOD funding opportunities and best practices in writing effective technical proposals. Representatives from the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Army, Navy, Air Force, and other federal agencies present funding opportunity information along with insights on writing competitive proposals in response to Broad Agency Announcements and other funding opportunities. The Defense Innovation Marketplace provides

___________________

6 For more information, see https://DODhbcumiopportunities.com/.

7 For information on the ONR Young Investigator Program, see https://www.nre.navy.mil/education-outreach/sponsored-research/yip. For the Air Force Research Laboratory Young Investigator Program, see https://afresearchlab.com/. For the DARPA Young Faculty Award, see https://www.darpa.mil/work-with-us/for-universities/young-faculty-award.

8 For more information, see https://DODhbcumiinternship.com/.

9 For more information, see https://DODstem.us/.

10 For more information on SMART, see https://www.smartscholarship.org/smart.

opportunities such as Technology Interchange Meetings and Communities of Interest.11

RECOMMENDATION 4-2: Beginning in FY2026, the DOD Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering should collect and publish data annually that measure the efficacy of existing outreach programs targeting MSIs, and share lessons learned with DOD agencies to accelerate the dissemination of best practices.

-

This report should include a longitudinal analysis to provide evidence of successful engagement and impact. Potential metrics should include the following:

- Number of MSIs engaged quarterly,

- Data on personnel interacted with (investigators, administrators, students),

- Institution type,

- Hours and type of engagement,

- Number of applications received and time to successful award, and

- Measurement of research infrastructure growth among awardees (instrumentation, research-engaged faculty, administration support, etc.).

Metrics collected should be used to set a baseline for improvement of how the DOD engages with MSIs. They should be assessed annually to direct resources and engagement activities toward increased participation in DOD R&D.

-

The DOD Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering should administer new outreach programs that do the following:

- Create and deploy a DOD liaison to HBCUs, TCUs, and MSIs to translate DOD interests to the university and university capabilities and interests to the DOD.

- Place scientists and engineers from local military labs at MSIs to teach STEM courses and provide course load relief for investigators pursuing and conducting defense-related research, as referenced in Chapter 3. A potential framework

___________________

11 For more information, see https://defenseinnovationmarketplace.dtic.mil/about/. For the Communities of Interest, see https://defenseinnovationmarketplace.dtic.mil/communities-of-interest/. For business opportunities, see https://defenseinnovationmarketplace.dtic.mil/business-opportunities/.

- could be the use of the Intergovernmental Personnel Act Mobility Program.12

- The DOD Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering should expand existing outreach programs so that HBCU, TCU, and MSI employees are eligible for sabbaticals to gain R&D experience with DOD acquisition and operations organizations.

These new outreach programs will allow for increased awareness and provide teaching load relief to HBCU, TCU, and MSI faculty conducting DOD R&D. In doing so, however, DOD’s HBCU/MI programs should address institutions’ unique contexts and needs rather than group HBCU, TCU, HSI, and other MSI engagements. A one-size-fits-all approach decreases the successful engagement of MSIs, given the diversity of needs, challenges, engagement, and opportunities within and across MSIs. To plan and implement more granular interventions, the DOD should undertake robust comment periods, listening sessions, and dialogue with institutions and their supporting communities to develop engagement frameworks tailored to each MSI type to increase the Department’s success in its engagement with MSIs and relationship development activities. This approach is both in the strategic interest of the DOD and helps support global competitiveness, national security, and historic disparities.

Committee Analysis of DOD Opportunities

As noted above, a concern was expressed during the site visits and in other feedback from MSIs in which faculty researchers noted the complexity of the application process as a barrier to engaging with the DOD for research funding opportunities. Accepting that success rates are not high in any proposal-based award system, it is clear that there are advantages in having research officers and faculty who are well versed in how to interpret and respond to Requests for Proposals (RFPs) and who have the time and resources to develop proposals.

In this analysis, five active DOD RFPs/funding opportunity announcements (FOAs) were randomly selected from grants.gov, which had a total of 67 active RFPs/FOAs available for review at the time of the analysis. A

___________________

12 For more information, see https://www.doi.gov/pmb/hr/ipa-mobility-program.

content analysis followed by a thematic analysis were used to review the selected RFPs/FOAs.

Content analysis determined if each DOD RFP/FOA had the same core structures: (1) Program Overview, (2) Eligibility, (3) Submission Information, (4) Application Detail, and (5) Award Information (Table 4-1).

A thematic analysis of the content revealed several implications and learnings:

- No uniform RFP/FOA format. Unlike agencies such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) or NSF, there is no standard or uniformity to the design or order of information across the DOD RFPs/FOAs. This is true even within divisions; for example, W911NF-19-S-0001 and W911NF-19-S-0004, both supported by the Department of the Army Materiel Command, differed in font and design style and level of detail in each section (Table 4-2). The lack of standardization in the information provided in some RFPs/FOAs may contribute to challenges with accessibility for some RFPs/FOAs.

- Difference in evaluative criteria or expectations. For example, W911NF-19-S-0013 provides clear objectives to which applicants can respond, but other RFPs/FOAs do not include specific references to objectives, despite outlining criteria related to scientific merit, impact on the DOD mission, and innovation/relevance.

-

Inconsistent points of contact. Not all RFPs/FOAs had a designated point of contact. In some cases, a general program email was provided, while others did not include this information. In FOA-RVK-2019-001, for example, no email was provided, despite the instructions using the following language:

For administrative issues regarding this FOA, contact the grants specialist at the email address identified above. For technical issues regarding this FOA, please contact the Primary Technical POC at the email address identified above. All questions must be received in writing via email with the reference line referring to this notice (FOA-RVK-2019-0001).

- Inconsistency in feedback procedures. Some RFPs/FOAs state that feedback will only be provided to funded proposals. If feedback is only provided to competitive proposals, those applicants who did not receive funding will be at a disadvantage as they lack insight into steps they can take to improve a future submission.

Overall, the variation and diversity across DOD RFPs/FOAs in terms of their construction and submission processes may contribute to lower submission rates by MSIs who may lack the resources to navigate the DOD system. Akin to national standardized assessments like those used for collegiate or graduate school admission, if such tools change their structure each year, or differ by state, then it would systematically disadvantage a number of individuals. Such is the case with varying RFP formats and structures across the DOD. Further providing increased engagement of MSI researchers within review panels will help address potential implicit bias.

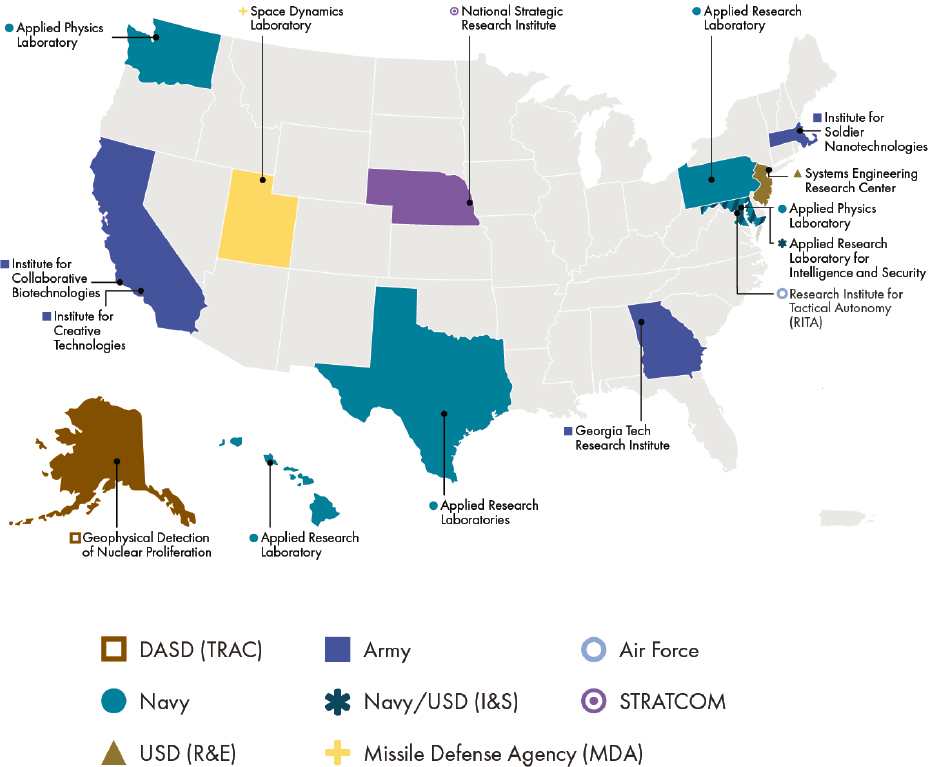

University Affiliated Research Centers and Federally Funded Research and Development Centers

The DOD has also created a network of 15 University Affiliated Research Centers (UARCs) and 10 Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDCs) (Tables 4-3 and 4-4). These centers vary in size with core competencies aligned to specific DOD needs. A high priority is placed on acquiring UARC and FFRDC unique technical expertise in areas in which the DOD cannot attract and retain personnel in sufficient depth and numbers on its own. The advantage to the UARC/FFRDC is the strong relationship developed with the DOD that can lead to substantial and sustainable investments.

A UARC is a nonprofit research organization within a university or college that provides or maintains essential DOD engineering, research, and/or development capabilities. Each UARC has core competencies in leading-edge research, development, or engineering that are tailored to meet the needs of the DOD. UARCs provide the DOD support in early S&T programs (6.1 and 6.2 research) as well as in advanced technical development, advanced component development, and prototype engineering programs (6.3 and 6.4) (DOD, 2024b).

The ongoing need for each UARC is evaluated every 5 years. Each UARC is required to operate in the public interest and conduct its business in a manner befitting its special relationship with the government. This

TABLE 4-1 Analysis of Five Randomly Selected DOD RFPs/FOAs

| RFP/FOA # | Overview Included | Eligibility Clear | Process for Applying | Description of Criteria | Miscellaneous |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BROAD AGENCY ANNOUNCEMENT (BAA) for Extramural Biomedical Research and Development (W81XWH-18-S-SOC1, Modified-004) | X | Award mechanism confusing: “The USAMRAA will negotiate the award types consisting of either contracts, grants or cooperative agreements for proposals/applications selected for funding.” |

“(1) pre-proposal/preapplication submission through eBRAP (https://eBRAP.org/) and (2) full proposal/application submission through Grants.gov or eBRAP, depending on the type of application being submitted.” “A Proposal/Application will not be accepted unless the PI has received an invitation to submit.” |

“Pre-Proposal/PreApplication Narrative (6-page limit):… Problem to Be Studied, Theoretical Rationale, Scientific Methods, and Design (Background/Rationale, Hypothesis/Objective and Specific Aims, Approach/Methodology); Significance, Relevance, and Innovation of the Proposed Effort (Significance and Relevance, Innovation); Proposed Study Design/Plan; Military Impact; Personnel and Facilities; Open Source/License/Architecture” | “PIs will be notified as to whether or not they are invited to submit full proposals/applications; however, they will not receive feedback (e.g., a critique of strengths and weaknesses) on their pre-proposals/pre-applications.” |

| “Pre-Proposal/PreApplication Supporting Documentation” “Thorough—narrative description” |

|||||

| ARL Strengthening Teamwork for Robust Operations in Novel Groups (STRONG) (W911NF-19-S-0001, amendment 9) | X | Table of contents does not align with the RFP/FOA |

Thorough for Grants.gov steps: “Project Summary/Abstract, Project Narrative (Chapter 1: Technical Component- Proposed Effort (approximately 4 pages, Proposed Innovation Summit Series Participation and Collaboration Development (approximately 1 pages); Chapter 2: Cost Component; Bibliography and Reference Cite; Facilities and Other Resources; Equipment; Data Management Plan” |

“Factor 1: Scientific Merit and Relevance Factor 2: Experience and Qualifications of Scientific Staff and Junior Investigator Development Factor 3: Collaboration/Ecosystem support Factor 4: Cost” | “Applicants will receive feedback regarding their proposal ONLY IF IT IS SELECTED FOR AWARD.” RFP/FOA thorough Review and Selection Process |

| AFRL RV-RD Assistance Instruments Announcement --AFRL Space Vehicles (RV) and Directed Energy (RD) University Assistance Instruments (FOA-RVK-2019-0001) | X | Not identified as Eligibility— “GENERAL INFORMATION: Only U.S./U.S. territory educational institutions are eligible to submit proposals in response to this notice” |

Project Narrative, “Identify and describe how the effort will provide assistance that will stimulate or support a public purpose; (b) Project Narrative - Statement of Work; (c) Project Narrative - Research Effort; (d) Project Narrative - Principal Investigator (PI) Time; (e) Project Narrative – Facilities; (f) Project Narrative – Special Test Equipment; (g) Project Narrative – Equipment” | Not thorough… “The recipient shall submit a proposal describing the proposed research project’s (1) objective, (2) general approach, (3) public purpose in accordance with 32 CFR § 22.205, and 22.215 and (4) impact on Department of Defense (DOD) mission. The proposal shall also contain any unique capabilities or experience you may have (e.g., U.S. Air Force, DOD, or other Federal laboratory).” | Point of contact (POC) present in RFP/FOA |

| Research and Education Program for Historically Black Colleges and Universities/Minority-Serving Institutions ((FOA) W911NF19-S-0013 Amendment 02) | X synopsis vs. overview | Must refer to original 2019 FOA “The ACC-APG RTP Division has the authority to award a variety of instruments on behalf of CCDC ARL. Anticipated awards under this FOA include grants and cooperative agreements” |

White paper: “TECHNICAL CONTENT (not to exceed five pages), ADDENDUM (not to exceed one page)” “Scientific Division(s) or Directorate(s), Technical Area(s)/Program Manager, The research to be undertaken in a level of detail that fully addresses the objectives of the research and approaches to be used, and the relationship of the project to the state of knowledge in the field and to any related work at the institution or elsewhere. vi. The anticipated results and how the project relates to the research interests of the Agency(ies). |

“ARL staff will perform an initial review of its scientific merit and potential contribution to the Army mission, and also determine if funds are expected to be available for the effort. Proposals not considered having sufficient scientific merit or relevance to the Army’s needs, or those in areas for which funds are not expected to be available, may not receive further review.…Each proposal will be evaluated based on the evaluation criteria in accordance with BAA W911NF-19- | RFP/FOA has objectives “Identified Specific Actions of the Senior/Key Personnel” (high/Moderate/Low ranking) rubric |

| vii. The facilities and equipment available for performing the proposed research. viii. The involvement of undergraduate and/or graduate students in the research project and associated research-related education is encouraged. Program funds may be requested for scholarships and fellowships pursuant to 10 U.S.C. 2362. The involvement of students in the research project is critical to achieving program objectives.” | S-0013. Each evaluated proposal will receive a recommendation of “select” or “do not select” as supported by the evaluation.” |

| BROAD AGENCY ANNOUNCEMENT (BAA) FOR BASIC AND APPLIED RESEARCH (W911QY-20-R-0022) | X | “Who may submit…” “Types of instrumentation… Combat Capabilities Development Command (CCDC), Natick Contracting Division has the authority to award procurement contracts, cooperative agreements, and grants, and reserves the right to use the type of instrument most appropriate for the effort proposed.” |

“Concept papers may not exceed 5 single-sided 8 ½ x 11 inch typed pages (including charts, graphs, photographs, etc.) and shall include the following: (1) A brief technical explanation of the proposed effort that addresses the major research thrust, the research goals and deliverables, a proposed approach to achieve these goals and deliverables, and military relevancy. (2) A brief ‘management’ description outlining key personnel and experience. (3) Any past performance the contractor has with similar research efforts. (4) An estimated cost/price and performance schedule for the work.” | Part I - Technical Section Part II - Management Section Part III - Cost/Price Section Part IV - Past Performance Section Part V – Subcontracting & Small Business Participation Part VI - Contractor Representations and Certifications Part VII - Contractor Statement of Work |

The clearest table of contents of all the RFPs. Additional paperwork: “contractor manpower reporting requirements”; “Executive compensation reporting”; “Government furnished Property request” |

SOURCE: Committee-generated.

TABLE 4-2 Comparison of Proposal Requirements for Two DOD RFPs/FOAs

| W911NF-19-S-0001 | W911NF-19-S-0004 | |

|---|---|---|

| Special Notes | Format of announcement chart | |

| Table of Contents | Text without subheadings | Outlined Chart with subheading text |

| Program Description | Background, Cycle Structure, Deliverables, Updates | 16 areas of interest |

| Award Information | Definition of funding types | List of federal regulations |

| Eligibility | 3 sections (applicant, cost sharing, other) | 2 sections (applicant & cost sharing) |

| Submission Information | 11 sections across 11 pages | 8 sections across 16 pages |

| Application Review Information | 3 sections (criteria, review & selection process, recipient qualifications across 2 pages) | 3 sections (criteria, review & selection process, recipient qualifications across 10 pages to include definitions, Army Research Risk Assessment Program (ARRP) rubric, and required actions by applicants) |

| Award Administration | 5 sections over 4 pages | 3 sections over 14-pages |

| Agency Contact | Paragraph directions, general email | 4 enumerated directions, general email |

| Other Information | Human Subjects Directions | Example of Cost Proposal Budget Narrative Example of Budget Narrative for Grant and Cooperative Agreement Proposal Appendix with Acronyms |

SOURCE: Committee-generated.

TABLE 4-3 DOD University Affiliated Research Centers

| DOD UARC | University | Primary Sponsor | Founded |

|---|---|---|---|

| Georgia Tech Research Institute | Georgia Institute of Technology | Army | 1995 |

| Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | Army | 2002 |

| Institute for Collaborative Biotechnologies | University of California, Santa Barbara | Army | 2003 |

| Institute for Creative Technologies | University of Southern California | Army | 1999 |

| Applied Physics Laboratory | The Johns Hopkins University | Navy | 1942 |

| Applied Research Laboratory | Penn State University | Navy | 1945 |

| Applied Research Laboratory | University of Hawaii | Navy | 2008 |

| Applied Research Laboratories | University of Texas at Austin | Navy | 1945 |

| Applied Physics Laboratory | University of Washington | Navy | 1943 |

| Space Dynamics Laboratory | Utah State University | Missile Defense Agency (MDA) | 1996 |

| Systems Engineering Research Center | Stevens Institute of Technology | USD(R&E)/ADF(MC) | 2008 |

| Applied Research Laboratory for Intelligence & Security | University of Maryland, College Park | USD(I) | 2017 |

| National Strategic Research Institute | University of Nebraska | STRATCOM | 2012 |

| Geophysical Detection of Nuclear Proliferation | University of Alaska | DASD(TRAC) | 2018 |

| Research Institute for Tactical Autonomy | Howard University | USAF | 2023 |

SOURCE: Committee-generated.

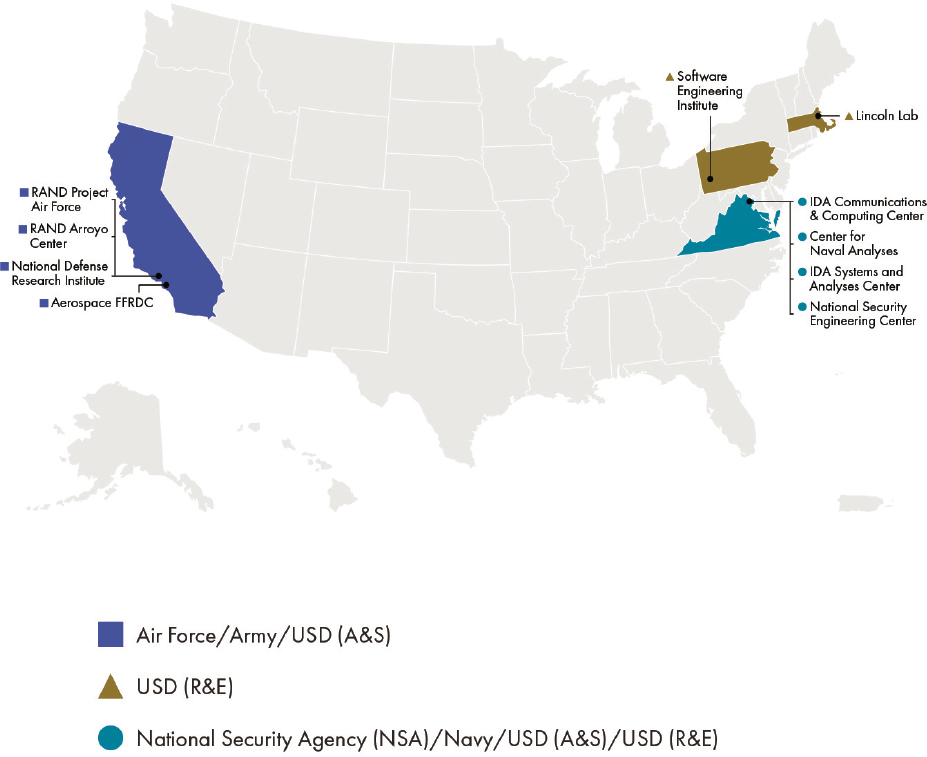

TABLE 4-4 DOD Federally Funded Research and Development Centers

| DOD FFRDCs | Primary Sponsor | Founded |

|---|---|---|

| Study & Analysis | ||

| Center for Naval Analyses | Navy (ASN(RDA)) | 1942 |

| Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA) -Studies and Analyses | USD(A&S) | 1956 |

| RAND – Arroyo Center | HQDA G-8/PAE | 1982 |

| RAND – National Defense Research Institute (NDRI) | USD(A&S) | 1984 |

| RAND – Project Air Force | Air Force (SAF/AQ) | 1948 |

| Systems Engineering & Integration | ||

| Aerospace Corporation | Air Force (SAF/AQ) | 1961 |

| MITRE Corporation – National Security Engineering Center (NSEC) | USD(R&E) / ASD(S&T) | 1958 |

| Research & Development Laboratories | ||

| Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA) – Communications & Computing | National Security Agency | 1959 |

| Massachusetts Institute of Technology—Lincoln Laboratory (MIT/LL) | USD(R&E) / ASD(S&T) | 1951 |

| Software Engineering Institute (SEI) | USD(R&E) / ASD(S&T) | 1984 |

SOURCE: Department of Defense Research and Engineering Enterprise. Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDC) and University Affiliated Research Centers (UARC). https://rt.cto.mil/ffrdc-uarc/.

includes operating under a comprehensive policy limiting its operations to be free from conflicts of interest. Generally, UARCs may not compete against industry in response to competitive RFPs for development or production contracts. They are required to maintain a long-term strategic relationship with the DOD in a manner that provides the following:

- Responsiveness to evolving sponsors’ requirements.

- Comprehensive knowledge of sponsors’ requirements and problems.

- Broad access to information, including proprietary data.

- Broad corporate knowledge.

- Independence and objectivity.

- Quick response capability.

- Current operational experience.

- Freedom from real and/or perceived conflicts of interest.

The present set of 15 DOD UARCs (Table 4-3) includes one managed by an HBCU. Other MSIs have been involved in UARCs but generally in a small role. There is potential for more substantive involvement of MSIs when expertise is aligned with the mission of the UARC. For example, in a presentation to the committee, the director of the UARC at the University of Alaska expressed a willingness to increase engagement with MSIs with geoscience faculty.

FFRDCs are independent, nonprofit research organizations that are established and funded to meet specific long-term engineering, research, development, or other analytic DOD needs that cannot be met as effectively by government or industry resources. FFRDCs are operated and managed by nonprofit corporations; one is affiliated with the university (Massachusetts Institute of Technology/Lincoln Labs). FFRDCs are required to operate in the public interest and conduct business in a manner befitting their special relationship with the government, including a comprehensive conflict of interest policy. Each FFRDC is assigned a primary sponsor responsible for implementing the DOD’s policies and procedures, assessing its performance, maintaining the tenets of the sponsoring agreement, conducting a comprehensive review every 5 years, and approving all work done by the center (DOD, 2024b). The present set of 10 FFRDCs is listed in Table 4-4.

Leaders from several UARCs and FFRDCs spoke with the committee at its open sessions. Common themes from these conversations were that centers did the following:

- Built up unique facilities, capabilities, and experiences that meet specific needs of the DOD.

- Emphasized strong and nearly singular organizational alignment with U.S. defense and national security priorities.

- Sought to increase diversity in their S&T workforce including graduates of HBCUs, HSIs, and TCUs.

- Developed, to greater or lesser extents, research collaborations and personnel exchanges with a broad set of universities to foster defense-related research across institutions, including engagement with HBCUs, HSIs, and TCUs.

- Engaged with the National Society of Black Engineers, Society of Hispanic Professional Engineers, Advancing Minorities, Interest in Engineers, and other organizations to accelerate the growth of a diverse workforce into S&T education and career paths.

Through its present set of UARCs and FFRDCs, the DOD has a research network that spans most of the United States (Figures 4-2 and 4-3). Many UARCs and FFRDCs are located relatively close to MSIs. While most TCUs are not geographically close to existing UARCs, there may be an opportunity for the DOD to take advantage of this proximity for greater engagement by UARCs and FFRDCs with MSIs.

In addition, the DOD consistently collects metrics on the performance of its UARCs and FFRDCs in terms of small and disadvantaged business engagement. The committee believes it would be instructive to collect similar data regarding the research connectivity between DOD UARCs, FFRDCs, and the HBCUs, TCUs, HSIs, and other MSIs in their region. Furthermore, the DOD, UARCs and FFRDCs will need to assess the unique opportunities, challenges, and risks of developing these partnerships in order to develop sustainable relationships.

RECOMMENDATION 4-3: The DOD should allocate resources to assess the potential for regional connectivity and partnerships between existing DOD labs, UARCs, and FFRDCs, and local or regional HBCUs, TCUs, and MSIs. This assessment should include collecting metrics on existing and potential research collaborations between these entities.

- Based on this assessment described above, the DOD should provide guidance to DOD labs, UARCs, and FFRDCs about how to support and expand collaborative R&D with MSIs within proximity or sharing similar research foci.

SOURCE: Defense Innovation Marketplace, https://defenseinnovationmarketplace.dtic.mil/ffrdcs-uarcs.

- The DOD should develop a pilot funding opportunity that allows MSI investigators to develop research projects with investigators at DOD labs, UARCs, and FFRDCs. Awards should include MSI investigators as lead investigators, co-investigators, or lead contractors.

OTHER AGENCY MODELS AND OPPORTUNITIES

Defense-related research is sponsored not only by the DOD but also by other federal agencies. It includes basic and applied research that supports the national security of the United States and is useful to DOD force readiness. In addition to the DOD, federal agencies, such as NIH, NSF, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), Environmental Protection Agency, and Department of Energy (DOE), sponsor research

SOURCE: Emerging Technology Policy Careers, the Horizon Institute for Public Service, https://emergingtechpolicy.org/institutions/national-labs-and-ffrdcs/#:~:text=Overview%20of%20the%20national%20labs%20today,-Beyond%20the%20 nuclear.

and scholarship at HBCUs, HSIs, and TCUs in domains useful to national security. Examples include, but are not limited to, studies in materials science, microbiology, toxicology, marine science, and oceanography.

Other federal agencies recognize the need to provide funding that precipitates new applications in R&D and a more diverse, STEM-capable workforce. These agencies have developed and administered programs throughout their history in an effort to increase representation and engagement of under-resourced and underinvested institutions and communities. A long-standing example can be found in NSF’s proposal criteria included as part of its Broadening Participation Portfolio (NSF, 2011; James and Singer, 2016). Applicants must show how their proposed research will benefit society and contribute to the achievements in specific, desired societal impacts. While imperfect and drawing criticism from NSF’s funded

community (e.g., Tretkoff, 2007), this requirement signals to current and future grantees, grant reviewers, and staff that increasing participation from under-resourced institutions and communities is important to the science, engineering, and innovation ecosystem and to the nation. NSF’s Broadening Participation Portfolio seeks to broaden the gender, racial, ethnic, and geographic diversity among fund awardees.

This level of intentionality manifests across federal science agencies with programs that offer support to faculty and trainees; target funding for capacity, both physical and administrative; and increase opportunities for the development of institutional partnerships. The committee hosted representatives from several science funding agencies during open sessions to better understand the breadth of interventions used across the federal government. In addition, the committee drew on discussions during the Town Hall series referenced in Chapters 1 and 3 (NASEM, 2024). As in the case of looking at DOD programs, the summary below is not an exhaustive view of every program across the federal government. Instead, the summary highlights examples of how other federal agencies have increased engagement with underinvested institutions that may inform the DOD as it considers how to develop or reconfigure its own programs.

Individual Support

The development of funding mechanisms that provide individual researchers and students with support to pursue degrees and advance areas of national need in STEM has long been a practice at federal funding agencies. The NSF Graduate Research Fellowship, which provides 3 years of funding for research-focused master’s and doctoral students, is an integral mechanism for supporting the training of a generation of future innovators and contributors to U.S. R&D (NSF, 2024). At NIH, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Maximizing Opportunities for Scientific and Academic Independent Careers (MOSAIC) program provides a framework to support the successful transition of postdoctoral scholars to faculty positions. Through the MOSAIC program, individuals receive independent support. Additionally, organizations, such as scientific societies, can receive funding to develop networks that offer mentoring, networking, and career development across relevant research fields (NIH, 2024b). The NIGMS Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award (MIRA) provides targeted funding for established and new investigators with a specific funding mechanism for early-stage investigators (NIH, 2024a). MIRA

is designed to provide stable funding over a 5-year period to investigators pursuing research within the NIGMS mission to develop and support their labs. MIRA is broken out into tracks for established, new, and early career investigators to help address competition among different career levels while maintaining support for investigators across their careers. This stability and tailored funding addresses the needs of investigators throughout their careers to ensure that NIGMS is not only launching the next generation of researchers but also retaining them in the research enterprise for sustained advancement and contribution to the NIGMS R&D portfolio.

Findings:

- The R&D workforce can be expanded and strengthened through synergistic programs that create continuous funding sources for trainees (undergraduate, graduate, postdoctoral) and faculty researchers, with a specific target for MSIs. As an example, NIH allots funding for individual trainees or faculty that provides flexibility and independence. This funding covers periods of time for stability at the trainee level (~3 years) and for the establishment of a research lab (5+ years).

- Programs that are decoupled across career levels and previous engagement with an agency’s funding can support early, mid-, established, and new researchers.

Capacity Building

A diverse range of potential interventions can increase the capacity of MSIs to participate in federal R&D, defense-related or otherwise. Legislation, such as the CHIPS and Science Act, the DOE Science for the Future Act, FY22 and FY23 National Defense Authorization Acts, and others, detail the importance of increasing the capacity of underinvested and under-resourced institutions to contribute to the nation’s workforce, innovation ecosystem, competitiveness, and national security (U.S. Congress, 2021, 2022a, 2022b). Among the programs administered across the federal government, several frameworks, if appropriated or incorporated into existing programmatic structures, could increase the ability of MSIs to be significant contributors to DOD’s R&D ecosystem.

For example, NASA’s Science Mission Directorate (SMD) Bridge Program addresses capacity development of underinvested institutions that have not historically been a part of its performer base in an intentional and

structured way (NASA, 2024). The SMD Bridge Program is organized across two tracks: seed grants and full Bridge funding. Seed grants are budgeted for 2 years of support at up to $300,000. They are designed to build and strengthen partnerships between targeted institutions and develop the foundation necessary for institutions to successfully compete for major NASA grants and full Bridge Program funding.

Like the NIGMS MIRA program mentioned in the previous section, the SMD Bridge Program is designed to develop sustainable research programs and relationships to advance the NASA mission directorate’s five science divisions. Unlike MIRA, however, the SMD Bridge Program gears its funding toward institutions historically under-resourced by NASA, which include the breadth of MSIs and primarily undergraduate institutions (PUIs). It seeks to develop lasting collaborations between NASA’s existing infrastructure, such as its centers, labs, and R1 institution performers, and MSIs. An integral component of the SMD Bridge Program is an ongoing assessment and adjustment of what is effective and not effective. Throughout the creation and administration of the funding opportunity, regular community input is solicited and incorporated through virtual workshops to integrate the target community’s perspective into each iteration of the funding opportunity. Proposals are submitted by faculty at an MSI/PUI and co-written with a NASA partner with paid research positions for students on topics relevant to NASA’s divisions and an emphasis on sustainability and mentorship. To add more flexibility to the types of projects that institutions can pursue, the SMD Bridge Program tiers its funding for bridge awards at small (<$70,000), medium (<$150,000), and large or key proposals (<$500,000), with the large or key proposals having a maximum budget of $2 million per year and required to incorporate the development of a consortium that serves multiple MSIs/PUIs.

The DOE’s Reaching a New Energy Sciences Workforce (RENEW) and Funding for Accelerated, Inclusive Research (FAIR) programs were also developed with a significant amount of community input to ensure that the programs’ frameworks adequately approach addressing historical barriers to engagement in the DOE’s research ecosystem. These programs provide priority for underinvested institutions and institutions that have received no prior funding from DOE’s Office of Science (U.S. Department of Energy, 2023). RENEW is intended to provide direct support for teaching staff, administration, instrumentation, and students (U.S. Department of Energy, n.d.). FAIR is geared toward building research programs at MSIs and emerging research institutions (U.S. Federal Register 42 USC § 18901(5)).

Similar to NASA’s SMD Bridge, FAIR provides support for underinvested institutions to develop sustainable research partnerships between target institutions, national labs, and Office of Science user facilities.

Both NASA and DOE have delineated an intentional effort to address implicit bias and diversity in grant reviews and reviewers. Reviewers are given explicit direction and orientation on implicit bias awareness and mitigation strategies to support a more comprehensive and fair evaluation of institutions that either have never been a part of the funded community or do not align with assumptions of what a normal performer could be.

NSF’s Growing Research Access for Nationally Transformative Equity and Diversity (GRANTED) addresses another component of capacity development highlighted in the National Academies’ 2022 study, specifically a strong institutional research and contract base and ancillary services. GRANTED funding is geared toward providing support for the development of best practices and processes for institutional grant administration, human capital, and the translation of best practices to practical applications. Recognizing that there is no one-size-fits-all mechanism for increasing capacity, GRANTED is designed to collect a comprehensive scope of the diversity of interventions necessary for increasing capacity at non-R1 institutions and use that information for cross-pollination of ideas and the development of new programs to address critical needs across institutions.

Through the Department of Commerce, the Economic Development Administration Regional Technology Innovation Hub (Tech Hub) program may serve as a framework for pooling DOD’s resources while supporting infrastructure needs of MSIs. Strategic development grants are used to assess the effectiveness of a regional hub to support cross-sectoral consortia that collaborate toward an identified technology focus. An analogous hub that pools resources toward a single institution or organization to focus DOD support and leverage administrative capabilities, resource coordination for student and faculty opportunities at DOD labs, technology transfer, and engagement with funding programs could be an effective mechanism for increasing engagement of MSIs in DOD R&D.

Findings:

- The DOD and other federal agencies have implemented a diverse suite of interventions that addresses the complexity of capacity needs of MSIs.

- To compete for funding, MSI research capacity needs to encompass research capabilities and instrumentation, maintenance, and administration.

- Programs that target underinvested MSIs should be explicit, set eligibility metrics that identify a maximum of previous support, and set funding levels across tiers or tracks that allow for flexibility and sustainable investments in the institution’s research capacity development.

- Consortia across and within MSIs and other institutions leverage institutional capabilities and build infrastructure through collaborative activities and are particularly valuable for capacity building when led by investigators at MSIs.

- The defense R&D workforce can be expanded and strengthened through synergistic programs that create continuous funding sources for trainees (undergraduate, graduate, postdoctoral) and faculty researchers, with a specific target for MSIs. As an example, NIH allots funding for individual trainees or faculty that provides flexibility and independence and covers periods for stability at the trainee level (~3 years) and for the establishment (5+ years) of a research lab. Programs that are decoupled across career levels and previous engagement with an agency’s funding can support early, mid-, established, and new researchers.

RECOMMENDATION 4-4: The DOD Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering should create programs for evaluating and assessing MSI institutional capacity building. Specifically, this would include a program that supports the development of a “lessons learned” report on building, operating, and maintaining lab infrastructure to conduct unclassified R&D at MSIs. Special considerations should also be given to the unique ability of many MSIs, such as TCUs, to conduct classified research and to the strategic advantage of geographic locations like institutions that are remote. These additional funds should be aimed at understanding and communicating information relevant to long-term capacity building at MSIs. Information that could be examined in such a report might include best practices for the following:

- Standardizing and accelerating institutional R&D capability with a focus on physical plant and equipment investments;

- Increasing the institutional success rate;

- Identifying strategies for developing partnerships with non-R1 MSIs; and

- Identifying approaches by institution type (HBCU, TCU, nonR1 MSI), highest degree offered, level of research engagement, and geography.

REFERENCES

DOD (U.S. Department of Defense). 2023. DOD Budget Request: Defense Budget Materials - FY2023. Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller). https://comptroller.defense.gov/Budget-Materials/Budget2023/.

DOD. 2024a. DOD Budget Request: Defense Budget Materials - FY2024. Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller). https://comptroller.defense.gov/Budget-Materials/Budget2024/.

DOD. 2024b. Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDC) and University Affiliated Research Centers (UARC). https://rt.cto.mil/ffrdc-uarc/.

James, S.M., and S.R. Singer. 2016. From the NSF: The National Science Foundation’s investments in broadening participation in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education through research and capacity building. CBE Life Sciences Education, 15(3), fe7. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-01-0059.

NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). 2024. Science Mission Directorate (SMD) Bridge Program. https://science.nasa.gov/researchers/smd-bridge-program/.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2019. Minority serving institutions: America’s underutilized resource for strengthening the STEM workforce. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25257.

NASEM. 2020. Evaluation of the Minerva Research Initiative. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25482.

NASEM. 2022. Defense research capacity at historically black colleges and universities and other minority institutions: Transitioning from good intentions to measurable outcomes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26399.

NASEM. 2024. Building defense research capacity at historically black colleges and universities, tribal colleges and universities, and minority-serving institutions: Proceedings of three town halls. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/27511.

NIH (National Institutes of Health). 2024a. Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award (MIRA) (R35). National Institute of General Medical Sciences. https://www.nigms.nih.gov/Research/mechanisms/MIRA/Pages/default.aspx.

NIH. 2024b. Maximizing Opportunities for Scientific and Academic Independent Careers (MOSAIC) (K99/R00 and UE5). National Institute of General Medical Sciences. https://nigms.nih.gov/training/careerdev/Pages/MOSAIC.aspx.

NSF (National Science Foundation). 2011. Perspective on broader impacts. NSF 15-008. https://nsf-gov-resources.nsf.gov/2022-09/Broader_Impacts_0.pdf.

NSF. 2024. NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program (GRFP). https://www.nsfgrfp.org/.

Tretkoff, E. 2007. NSF’s “broader impacts” criterion gets mixed reviews. American Physical Society News, 16(6). https://www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/200706/nsf.cfm.

U.S. Congress. 2021. H.R. 3593 - Department of Energy Science for the Future Act. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/3593/.

U.S. Congress. 2022a, June 30. H.R. 7900 (RH) - National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/BILLS-117hr7900rh.

U.S. Congress. 2022b. H.R. 4346 - Chips and Science Act. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/4346.

U.S. Department of Energy. n.d. Reaching a New Energy Sciences Workforce (RENEW). Office of Science. https://science.osti.gov/Initiatives/RENEW.

U.S. Department of Energy. 2023. Funding for Accelerated, Inclusive Research (FAIR). Office of Science. https://science.osti.gov/Initiatives/FAIR.

This page intentionally left blank.