A Plan to Promote Defense Research at Minority-Serving Institutions (2024)

Chapter: 5 Setting a Path Forward for Assessment and Decision-Making

5

Setting a Path Forward for Assessment and Decision-Making

Systemic issues persist that impact of the ability of the Department of Defense (DOD), minority-serving institutions (MSIs), and their respective communities to assess existing capabilities, make decisions, and support growth in capacity for defense-related research and development (R&D). Previous reports have spotlighted challenges with collecting and utilizing data and operationalizing frameworks that effectively assess and articulate existing capabilities. Historical inequities in decision-making within the DOD and other federal agencies have further engrained inaccurate perceptions of MSIs that have hindered their growth in the R&D landscape.

This chapter describes several intervention mechanisms that target institutional planning and practices, decision-making at the DOD, more equitable facilities and administration (F&A) recuperation, and effective frameworks for data collection on MSI capabilities.

ADAPTING A RESOURCE-BASED ASSESSMENT OF MSIs

In considering approaches in how to identify the assets that MSIs bring to the DOD, the committee turned to the Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage. This seminal theory in the field of organizational development was first developed by Robert W. Grant more than 30 years ago. It emphasizes the importance of an organization’s internal resources and capabilities to achieve a sustainable competitive advantage, and purports the long-term success for an organization is grounded in use

of internal resources to contribute to its higher productivity. Moreover, it can account for the differentiations in internal resources (Barney, 1991) that would be expected at varying types of MSIs. The theory is also supported by the literature on the impact of internal resources on organizational success (Holdford, 2018).

Overview of Grant’s Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage

The basis of Grant’s theory was built on work nearly a decade earlier by Birger Wernerfelt (1984) who posited that organizations could outperform rivals when they leveraged unique, valuable, rare, or difficult-to-imitate resources and capabilities. Historical research in the field began with basic SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis methods. This approach allows organizations to maximize internal strengths and external opportunities while concurrently mitigating threats and avoiding weaknesses (Barney, 1991). Two schools of thought around organizational competitiveness existed prior to Grant’s work: a resource-based model and an environmental model (Barney, 1991).

The environmental model has several assumptions that are not applicable or relevant to MSIs and, in many aspects, all institutions of higher education (IHEs). One key assumption in an environmental model is that organizations in a specific field have the same relevant resources and use the same strategies to pursue competitiveness (Barney, 1991). This is not the case with MSIs, where evidence supports systemic occurrences of underfunding or under-resourcing (Adams and Tucker, 2022). Moreover, MSIs have not only unique student bodies but also difficult-to-imitate intellectual resources and human capital given the demographic composition of their institutions.

In contrast, the resource-based model examines the relationships between performance and an organization’s internal resources, which allows a differentiation between organizations rather than the perceived homogeneity that an environmental model assumes (Barney, 1991). As such, the Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage has emerged as a counter to the traditionalist research in strategic management because it is more responsive to the individuality that exists across industries, organizations, and the assets that each organization is able to capitalize or maximize for its own benefit. Environmental models for competitive advantage do not consider these differentiating factors or variables.

Understanding the Key Elements of the Resource-Based Theory in the MSI Context

Five elements of contextual significance in Grant’s Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage apply to MSIs.

First, as noted above, understanding the heterogeneity among organizations is foundational; resource heterogeneity means organizations possess different types of resources and capabilities that lead to performance variations. The performance effects of an organization’s strategy depend on the firm’s individual resources and capabilities and setting within which it is operating. For MSIs, this principle undergirds the equity-centered approach taken during the 2022 National Academies’ consensus study Defense Research Capacity at Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Other Minority Institutions and its resulting recommendations and findings (NASEM, 2022).

The second principle of relevance is resource immobility, in which resources and organizational capabilities may be difficult for competitors to obtain or replicate. The social complexities that contribute to the factors and characteristics of MSIs are part of that immobility.

The third principle is the role of a value, rarity, inimitability, and organization (VRIO) framework. Through this framework, organizations can assess their resources and capabilities to determine their sustained competitive advantage that could result in increased R&D or cooperative agreement funding acquisition. What is most critical to this assessment framing is that an organization’s rare and irreplicable resources must be organized to provide a sustainable advantage, thus implying the need for internal systems.

The fourth principle relevant to MSIs is the dynamic capabilities of an organization. Not only do organizations need to possess valuable resources, but they also need the ability to adapt, reconfigure, or renew their resource base in response to changing market conditions or competitive pressures. For MSIs this includes being able to adapt academic programming or offerings, reconfigure infrastructural operations for R&D, and be dynamic enough to respond to changes in emerging or shifting science and engineering fields.

The fifth relevant principle in Grant’s Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage is the role of strategic implications. This concept emphasizes the need for an organization to focus internally on developing and leveraging its unique strengths rather than chasing external opportunities. The strategic focus on internal strengths is operationalized as investing

in human capital, technology, brand, or other intangible assets. For an MSI, this means not only research faculty and staff but also technology for a culture in which human capital can thrive.

More contemporary work in the Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage purports that “successful innovations are determined not just by the innovation [but are] also the result of the people involved, the organization(s) behind the innovation, contextual factors surrounding its implementation and dissemination, and the innovation’s benefits to stakeholders and the firm” (Holdford, 2018, p.1351). When applied to higher education, with its several layers of management (federal, state, local boards, etc.), the Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage makes sense for MSIs that are within these systems. The Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage helps to contextualize what the resources of an institution will include. For example, the intellectual capital of an MSI includes its human capital like faculty and staff experience or skills, executive processes and practices, and information repositories (Ahmadi et al., 2012; Lynch, 2015).

All of these were elements captured in the consensus study’s work to gauge the needs of MSIs in their engagement with the DOD. According to the Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage, the way an organization leverages its resources, as well as its ability to provide internal resources, will give it a competitive edge over other organizations.

RECOMMENDATION 5-1: MSIs that seek to increase their R&D footprint, elevate across Carnegie Classifications, and/or improve the rate at which they secure funding should develop an internal strategic plan that advances their R&D goals and clearly articulates their unique value. Such plans could include the following elements:

- Principles of the Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage.

- An institutional SWOT analysis or other strategic analysis to identify specific areas of DOD interest in which its capabilities could have outsized impact.

- A 10-year roadmap to guide and prioritize internal investments and engagement with relevant DOD sponsors. Investments could include infrastructure, instrumentation, personnel, curriculum, and/or services.

- For institutions with demonstrated need, the DOD and other federal agencies should provide grants for institutional assessment and strategic planning toward increased research engagement and capacity building.

ADDRESSING POTENTIAL BIASES IN AWARD DECISION-MAKING

Efficient decision-making is an absolute necessity as it impacts an organization’s ability to make choices that have the most impactful outcomes. This is particularly true in the context of the DOD. Warfighters engaged in battle must make split-second decisions to survive. A challenge for the DOD is that fast decision-making on the battlefield does not necessarily translate to the slow progression of thinking that happens in the research enterprise.

In new and complex situations, people tend to rely on previous experience in making split-second decisions about what to do (Williams, 2010). Nobel Prize recipient Daniel Kahneman delineated between two types of thinking and decision-making: fast, intuitive, and emotional as compared with slower, more deliberative, and more logical (Kahneman, 2011). Successful warfighters train to develop fast thinking. They are exposed to every imaginable situation to develop heuristics that will be almost reflexive in decision-making speed for battlefield success and survival (Williams, 2010). In contrast, research and discovery requires a deliberate, thoughtful process that evolves over time. Scientists train to be skeptical and slow thinkers. They train to avoid implicit bias by sharing ideas with others and having others replicate and question their methods and assumptions.

Many DOD decision-makers controlling the resources that are deployed to the research enterprise are individuals who came up through the military ranks and were trained and successful in using heuristics to think fast. Several participants shared with the committee their perspectives that heuristics-based fast thinking, while essential in many life-threatening situations, may lead to implicit biases that result in optimal, bad, or prejudicial decisions. Personnel from the Department of Energy and from the National Institutes of Health described training for program managers (PMs) and peer reviewers designed to examine and reduce implicit bias in proposal evaluation. An evaluation of the practices of PMs and decision-makers within the DOD that assesses the strategies used in the planning, development, and execution of R&D programs that support IHEs is necessary to develop interventions that better support increasing the number and types of institutions supported by the DOD.

In the DOD research enterprise, although a formal review process following a request for proposals is often employed, the PM still holds some autonomy to make funding decisions in allocation and de-allocation of resources. It is not simply a model where the low bidder wins the grant

or contract, or the best proposal offered wins the grant or contract. PMs use their own heuristics to assess the likely return on investment given the costs, the personnel, and the approach. With this autonomy and under pressure to show a return on investment for the resources they manage, participants shared their perception that PMs may rely on their fast thinking methods in award decisions. An analogy might be a stockbroker who is deciding whether to invest in blue chip stocks (i.e., known performers that are universities with billion-dollar research enterprises in this context) or startups (i.e., universities newer to the research game or that have low research expenditures). As is well documented, resources at U.S. universities are unequally distributed. The top 30 institutions in terms of R&D expenditures represent less than 3 percent of all IHEs yet account for about 42 percent of the total spent on R&D expenditures (NSF, 2023). The autonomy of PMs that allows for heuristics-based decision-making could be one causal factor that, over time, has led to this unequal distribution of resources. It is simply more expedient, and may seem less risky, to invest in the universities that are known performers than to seek out “startups” and universities newer to the research game.

Decision-makers could be incentivized to create diverse funding portfolios that include both the known performers (R1 universities) and the “startups” (non-R1 universities), or this could be a factor in their performance assessments. While these startups may come with greater risk, the opportunity for greater return on investment is also present. As outlined in Chapter 3, MSIs currently possess a diversity of capabilities that, if invested in, will yield dividends for the DOD through workforce development and novel approaches to pressing concerns of national security. Non-R1 MSIs that have yielded a high return include institutions such as North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, Morgan State University, and Howard University, the latter of which has been awarded as the lead of the first Historically Black College and University (HBCU)-led University Affiliated Research Center. Having a diverse portfolio of universities in the funding profile will help mitigate risk. As the 2022 National Academies’ report recommended (NASEM, 2022), these startups do require long-term investments due to historical underfunding in physical infrastructure and human capital. Hence, when PMs add these startup universities to their portfolio, they need to acknowledge the challenges that can come with the execution of the research at the university, while recognizing the value-add in the expertise and perspective of the institution that is part of the portfolio. The PM must support and give the startup time and opportunity to

build a resilient infrastructure, and more resources need to be provided to PMs to allow for greater risk to be taken in support of increasing the type and number of institutions supported. By having a diverse portfolio, natural mentor-mentee relationships can develop between established and startup universities to give PMs an effective yield on their investments.

RECOMMENDATION 5-2: The DOD should intentionally engage MSIs as part of its R&D portfolio to competitively seek the broadest range of ideas and innovators possible. Increasing the diversity of institutions and researchers actively engaged in DOD’s research ecosystem will support increased global competition, undergird national security, and increase innovations that protect the warfighter. In implementing this increased engagement, the following factors should be included:

- Metrics on the number of current and new grant awards and contracting programs to IHEs, with coding to identify MSIs by type, on an annual basis beginning in FY2026. Data should also capture dollar amounts for each award to establish a baseline for growth that dates back to FY2011.

- A tangible goal, set annually by the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, for growing the awards and contracts granted to MSIs as the lead applicants for funding opportunities for each program.

- An assessment by the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering of MSI success rates and program performer diversity at the end of each fiscal year. This metric can address DOD’s needs by capturing MSI engagement and project relevance to the Department’s mission as data for goal-setting in subsequent fiscal years.

- The introduction of training on best practices and implicit bias. The incorporation of best practices and training to address implicit bias in the grant-making process will equip PMs with tools to ensure assessments of institutions and funding decisions are devoid of any implicit biases that may impact proposals from previously under engaged institutions.

ADDRESSING INEQUITIES IN F&A RATES

An important aspect of increasing research capacity at any IHE is receiving adequate support to both conduct research and invest in that

institution’s F&A. Often referred to as “indirect costs,” or IDCs, negotiated F&A rates allow institutions to assess their existing research infrastructure and their built and human capital. Set percentages of F&A rates ensure that funds that are being received via mechanisms such as grants include enough reimbursement to support the current infrastructure fully. To ensure that an institution is receiving an adequate level of IDC reimbursement, it must negotiate its F&A rate with the federal government using either a short form or long form calculation. Short form calculations are a simplified method of calculating F&A rates that are typically reserved for institutions that receive less than $10 million in federal funding and use salary and wages to calculate their direct costs. The long form method is a more extensive calculation that requires more time to prepare, includes a space survey, and is more granular in how total direct costs are identified. While requiring more resources, the long form methodology allows for the most accurate accounting of existing research infrastructure and thus ensures that institutions can recover the maximum amount of funding available to maintain and support growth in their F&A.

The Negotiated Indirect Cost Rate Agreement and subsequent rates are generally negotiated between institutions and an agency representative of the federal government. They play a crucial role in sustaining the research enterprise by reimbursing universities for expenses that cannot be directly attributed to specific research projects but are incurred through the facilitation of research or sponsored programs. Significant differences in F&A rates between different types of institutions exist, particularly between research-intensive (R1) universities and HBCUs, Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs), and non-R1 Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs). These differences have far-reaching implications for the ability of non-R1 institutions to build administrative and research infrastructure, and ultimately provide equitable educational opportunities for their students that support skill attainment toward capable defense-related research workforce regardless of the institution that students choose to attend.

F&A rates can be traced back to the 1940s, when the federal government first recognized the need to reimburse universities for the IDCs associated with conducting federally sponsored research. The Office of Naval Research negotiated the first set of principles for determining IDC rates in 1947, which became known as the Blue Book. In 1958, the Bureau of the Budget (now the Office of Management and Budget) issued Circular A-21, establishing official guidelines for determining allowable IDCs at colleges and universities (U.S. Federal Register, 2000). In 2014, the Office

of Management and Budget introduced the Uniform Guidance (2 CFR Part 200), which consolidated and streamlined the guidelines for federal grants management. The Uniform Guidance includes the cost principles for determining allowable F&A costs, with specific provisions for colleges and universities (U.S. Federal Register, 2014).

In 2019, the Council on Government Relations (COGR), an association of the largest research institutions, published Excellence in Research: The Funding Model, F&A Reimbursement, and Why the System Works (COGR, 2019). As the title indicates, COGR supports the F&A model. From input in the open sessions, Request for Information results, and their own experiences, committee members have found this system seems to work best for institutions that have more than $15 million in research expenditures, but it neither works well nor is inclusive for other institutions below that threshold.

Calculating F&A Rates

F&A rates are calculated based on an institution’s indirect expenditure infrastructure and support services costs divided by their direct costs. These expenditure costs are grouped into various categories, such as depreciation, utilities, libraries, and administrative expenses. The difference between negotiating an F&A rate based on Modified Total Direct Costs (MTDC) versus salaries, wages, and fringe benefits, or just salaries and wages, lies in the cost base used to calculate and apply the F&A rate.

Modified Total Direct Costs: MTDC is the most commonly used base for calculating and applying F&A rates. It includes all direct salaries and wages, applicable fringe benefits, materials and supplies, services, travel, and up to the first $25,000 of each subaward (regardless of the period of performance of the subawards under the award). MTDC excludes equipment, capital expenditures, charges for patient care, rental costs, tuition remission, scholarships and fellowships, participant support costs, and the portion of each subaward in excess of $25,000 (2 CFR §200.68). When an institution negotiates an F&A rate based on MTDC, the rate is applied to the MTDC base of sponsored projects to determine the amount of F&A reimbursement. Significantly, the MTDC rate is only available to institutions that have over $10 million in research expenditures per year. Thus, this threshold excludes many HBCUs, TCUs, and HSIs that are not R1 institutions.

Salaries, Wages, and Fringe Benefits Base: In some cases, institutions may negotiate an F&A rate based on a cost base that includes only salaries,

wages, and fringe benefits. This means that the F&A rate is calculated by dividing the total F&A costs by the total salaries, wages, and fringe benefits of sponsored projects. When applying this rate, the institution multiplies the F&A rate by the salaries, wages, and fringe benefits charged to a sponsored project to determine the F&A reimbursement. This results in a lower F&A calculation than MTDC.

Salaries and Wages Base: Occasionally, institutions negotiate an F&A rate based solely on salaries and wages, excluding fringe benefits. In this case, the F&A rate is calculated by dividing the total F&A costs by the total salaries and wages of sponsored projects. The rate is then applied only to the salaries and wages charged to a sponsored project to determine the F&A reimbursement.

Disparities Between R1 Institutions and non-R1 MSIs

While the F&A rate calculation process is uniform across all institutions, there are significant variations in the rates negotiated by different types of institutions. Research-intensive (R1) institutions often have higher F&A rates compared to HBCUs, TCUs, and HSIs that are not R1s. There are several factors that contribute to this related to facilities and administrative support.

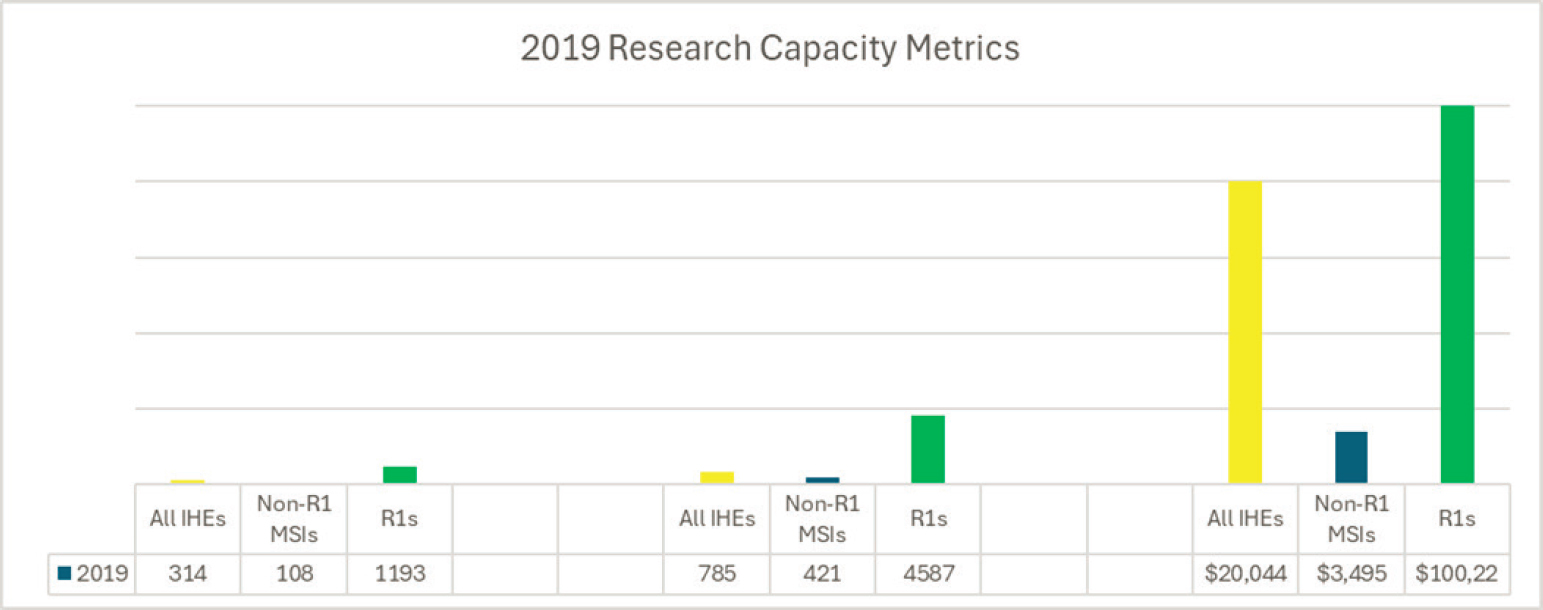

R1 institutions typically have not only more extensive and sophisticated research facilities, which result in higher costs for construction, maintenance, and operation, but also the availability of resources to monitor, catalog, and track the facilities. For example, several studies have been conducted regarding space utilization at colleges and universities across the country. State systems like University System of Georgia and the University of North Carolina system have funded studies to support the space utilization of their member institutions (Cheston, 2012; Janks et al., 2012; University System of Georgia, 2013). These studies improve utilization reporting and decision-making. Institutions external to state systems or without the operational infrastructure to develop utilization reports necessary for research and facilities space calculations do not have these costs reflected in their F&A rates. According to the Survey of Science and Engineering Research Facilities in 2019,1 colleges and universities reported an average of 314,732ft2 in research space. Underlying that average, however,

___________________

1 2019 data used for consistency across National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics Survey databases.

R1 institutions averaged 1,193,551ft2, while non-R1 MSIs averaged less than one-tenth that amount, or 108,622ft2. Those that can capture the extensiveness of their facilities fare better with their rates. Smaller under-resourced MSIs such as TCUs often lack the resources to invest in state-of-the-art research infrastructure and the capacity to capture current facilities, leading to lower F&A rates.

R1 institutions also have larger and more complex research administration operations, with dedicated staff to handle grant management, compliance, and other support functions. According to the National Science Foundation (NSF) National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, the average number of R&D personnel and staff at colleges and universities was 785 in 2019 (NSF, 2021a). However, R1 institutions reported 10 times more R&D personnel and staff than non-R1 MSIs, averaging around 4,587 compared to 421, respectively. These administrative costs are included in the F&A rates. Many HBCUs, TCUs, and non-R1 HSIs have smaller research portfolios, limited resources in personnel capacity, and less administrative support, resulting in lower calculated administrative costs and F&A rates.

Disparities in F&A rates have significant consequences for HBCUs, TCUs, and non-R1 HSIs (Figure 5-1). According to NSF Higher Education Research and Development (HERD) Survey data in 2019, colleges and universities reported recovering an average of $20,044,000 in IDCs (NSF, 2021b). Carnegie R1 institutions recovered an average $100,227,000, and non-R1 MSIs recovered an average $3,495,000. In other words, R1 institutions are recovering 33 times more in IDCs that they can use to reinvest, support equipment purchases or maintenance costs, hire new staff, or build and update facilities. Lower F&A reimbursements mean that MSIs have fewer resources to invest in building and maintaining research infrastructure, hiring administrative staff, and providing support services for researchers. This creates a self-perpetuating cycle in which MSIs struggle to compete for research funding, which in turn limits their ability to grow their research programs and negotiate higher F&A rates.

The differences in F&A rates can exacerbate existing inequities in higher education. TCUs, as an example, which primarily serve Native American students, often have limited financial resources and face unique challenges in providing educational opportunities to their communities. Lower F&A reimbursements further strain these resources, making it difficult for TCUs to offer their students competitive research opportunities and support services. The Tribally Controlled Community Colleges Assistance Act of 1978 (25 U.S.C. 1801) was designed to provide federal funding for the

operation and improvement of TCUs. However, this funding has not kept pace with the growth and evolving needs of TCUs, particularly in research infrastructure and support. As noted in Chapter 2, similar long-standing disparities exist for HBCUs.

Furthermore, federal research funding has traditionally been skewed toward R1 institutions, with MSIs receiving a disproportionately small share of research grants. This is partly due to the competitive nature of research funding, where institutions with established research programs and infrastructure have an advantage in securing grants. The lack of research funding for MSIs has made it challenging for these institutions to build the necessary infrastructure and administrative support to compete effectively for grants.

Findings:

- The F&A system seems to work best for institutions that have more than $15 million in research expenditures, but it neither works well nor is inclusive for other institutions below that threshold.

- An MSI seeking to grow its research enterprise should undergo a renegotiation of its existing F&A rates using long form calculations to calculate its existing infrastructure more accurately for more equitable research administration fund recuperation.

- MSIs should allocate resources to conduct periodic renegotiations to ensure that current F&A rates continue to reflect evolving research infrastructure.

RECOMMENDATION 5-3: To support the growth and development of research programs at MSIs, Congress should provide dedicated funding to help HBCUs, TCUs, and non-R1 HSIs build and maintain state-of-the-art research facilities and equipment. This investment will enable MSIs to compete more effectively for research grants. An example of a program that can be adapted is the 1890 Facilities Grant Program. A similar funding mechanism will provide support for the development and improvement of facilities, equipment, and libraries necessary to conduct defense-related research.

- Congress should also evaluate the effectiveness of the existing F&A de minimis rate2 and set a de minimis rate that does the following:

___________________

2 The de minimis IDC rate is 10 percent of an organization’s MTDC: 2 CFR 200.414.

- Allows for institutions seeking to increase R&D activity to receive a more adequate reimbursement for engagement in federally funded R&D.

- Is higher for smaller institutions to support increased engagement in federally funded R&D.

- Additionally, federal agencies should implement an F&A Cost Rate Support Project to provide ongoing technical assistance and support to MSIs in developing and negotiating their F&A rates. The basis of F&A rates for MSIs should be different than for other institutions because institutions with historic investments by states and the federal government benefit from the current structure while MSIs continue to suffer current inequities that are a direct consequence of prior investment disparities in research-focused facilities, equipment, and infrastructure. This will help ensure these historically disadvantaged institutions receive more appropriate F&A reimbursements for their research activities and increase their ability to contribute to U.S. R&D, global competition, and national security.

INCREASING DATA COLLECTION ON MSI CAPABILITIES

The National Academies’ study Defense Research Capacity at Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Other Minority Institutions (NASEM, 2022) discussed the need for more data to adequately assess and monitor ongoing efforts to build research capacity and increase the DOD research dollars going to HBCUs, TCUs, and HSIs. The report served as a cornerstone for the current study; it not only underscored the need for more data but also served as a compass to establish a baseline with data and metrics. With the right data and performance indicators, progress toward goals can be more effectively evaluated. Thus, the committee aimed to address a principle conclusion from the 2022 report: “There is insufficient data collection, inter-departmental program coordination, long-term records, and a lack of quantitative evaluations to appropriately assess the DOD’s (Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, military departments, and defense agencies) total investment and measurable impact on the advancement of HBCU/MI research capacity” (NASEM, 2022). As the committee embarked on implementing a framework for measurement and evaluation, it leaned heavily on the previous study as the standard for data and, with a few enhancements, the metrics used to assess progress. The

2022 National Academies’ report comprehensively documented a number of data sources, acknowledging their limitations and biases. One departure articulated here is to initiate an effort to gather data directly from the DOD. Constructing this new dataset can help directly confront the biases and limitations identified in current DOD data sources. This represents a significant step forward in the ability to measure and evaluate progress in terms of DOD funding for MSIs.

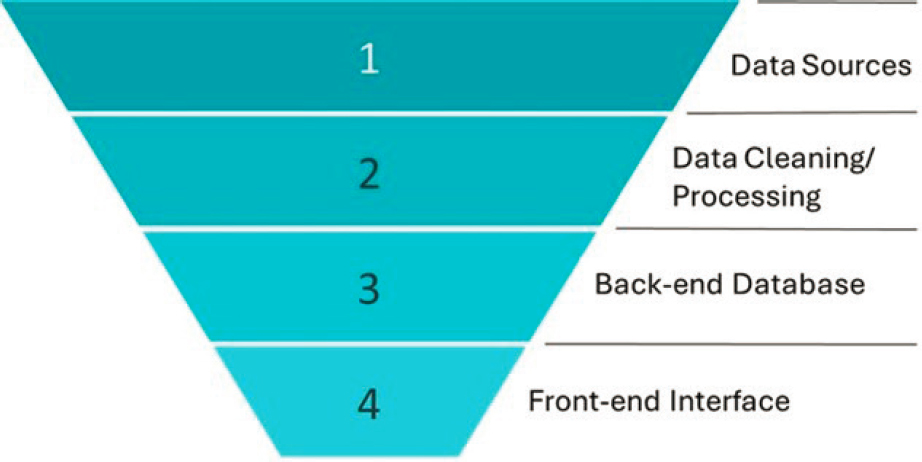

The data flow diagram (Figure 5-2) introduced below is that of an inverted pyramid. The final product is a dashboard combining the backend database with a frontend interface or dashboard. This dashboard, designed with customer needs in mind, allows the user to query and analyze the data. It could be a user-friendly application through which DOD personnel and other interested stakeholders can monitor and measure the progress by the DOD toward decreasing the R&D gap in dollar amounts awarded to majority institutions (i.e., R1s and others that have the highest DOD research expenditures) compared with MSIs. This tool can empower DOD policymakers to make informed decisions and drive positive change in the research funding landscape. When quantifying the gaps, the strategies for building capacity may emerge that help reduce the R&D gap—for example, new programs with graduate students or more research space and equipment. The caretaker for the data and tool should be a DOD-specific entity. A potential organization is the Defense Manpower Data Center where the data could be collected, updated, and stored. Moreover, the dashboard should be maintained and available for policymakers and their staff to access and analyze the information.

The 2022 National Academies’ study also included a recommendation to increase and measure the capacity of HBCUs, HSIs, TCUs, and other MSIs to address the engineering, research, and development needs of the DOD (NASEM, 2022, Recommendation 3C). The report stated that data collection and analyses should be performed on a continual basis for all DOD grants and contracts across all IHEs and should result in a formal annual report to the Office of the Secretary of Defense and Congress early in the calendar year to inform the development of future National Defense Authorization Acts and appropriation bills.

The current committee developed a four-part roadmap to guide the creation of a data-driven dashboard for the DOD that would inform its progress in closing the gap in R&D dollars awarded to MSIs (Figure 5-2).

SOURCE: Committee-generated.

The data-related processes outlined in 1 and 2 in the framework above include

- gathering the data,

- updating information, and

- adding additional information to the dataset as appropriate.

The DOD should link the back-end database (3) and the front-end interface (4) in order to retrieve and analyze the data.

The result of these activities is a tool used by DOD decision-makers to monitor and measure the degree to which the DOD mandate to promote defense research at HBCUs, TCUs, HSIs, and other MSIs is accomplished using the datasets produced.

Data Sources

The committee identified 11 sources of data (Table 5-1). The first seven were described in the 2022 report, and the final four were created from additional NSF and DOD sources. Furthermore, new information could be collected and added to the dataset, such as the number of proposals submitted and the number of awards received.

TABLE 5-1 Sources of Data Related to MSI R&D Expenditures

| # | SOURCE | DESCRIPTION OF DATA |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | USAspending.gov | Data on contracts and grants for institutions of higher education (IHEs) |

| 2 | National Science Foundation (NSF) | Information related to institutional capacity and to compare federal funding for different types of institutions |

| 3 | Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) | Used to consolidate recipient organization names and link the transaction dataset to other supplementary datasets |

| 4 | D&B Hoovers | Additional resource to assist with consolidating recipient organization names |

| 5 | Committee’s Minority Institution Identifier | Served as the primary identifier of the IHE category for the study |

| 6 | Rutgers Center for Minority Serving Institutions Directory of Institutions | Categorizes IHEs that were not already labeled as either MSIs or HBCUs using the committee-provided list |

| 7 | Carnegie Classification | Obtained to further delineate differences between institutions on the basis of the type of degrees awarded as well as the character of the research and scholarly activity |

| 8 | Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative (MURI) | Data on the number of proposals submitted and the number of awards received |

| 9 | Defense University Research Instrumentation Program (DURIP) | Data on the number of proposals submitted and the number of awards received |

| 10 | HBCU-MSI | Data on the number of proposals submitted and the number of awards received |

| 11 | NSF Higher Education Research and Development (HERD) | Data on the number of proposals submitted and the number of awards received |

SOURCE: Committee-generated.

Data Cleaning/Processing

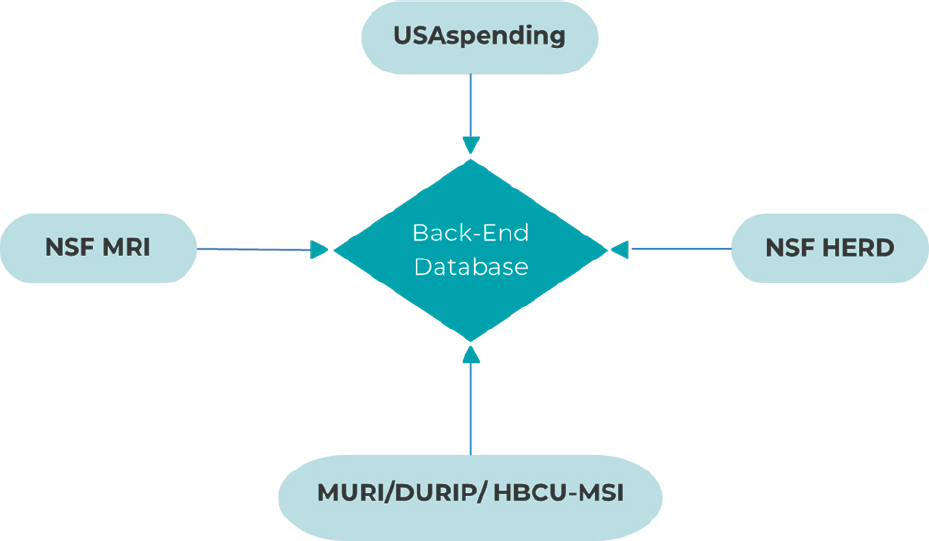

At the Data Cleaning and Processing stage, the DOD can develop four datasets that can be used to create the back-end database in Step 3 (see Figure 5-2). These datasets include the following:

- Transactional dataset from USAspending.gov in conjunction with the appended supplementary datasets

- NSF HERD (stand-alone)

- MURI/DURIP/HBCU-MSI winners dataset

- NSF Major Research Instrumentation (MRI) dataset

Back-end Database

Data tables would be created from the four datasets (Figure 5-3). The data tables are used in a back-end relational database to allow querying of the datasets. Building the back-end database to store, manage, and retrieve the data used involves ensuring that the datasets have common data that can be used to create the relationships in the database and that naming conventions are standard across all data tables.

SOURCE: Committee-generated.

Front-end Interface

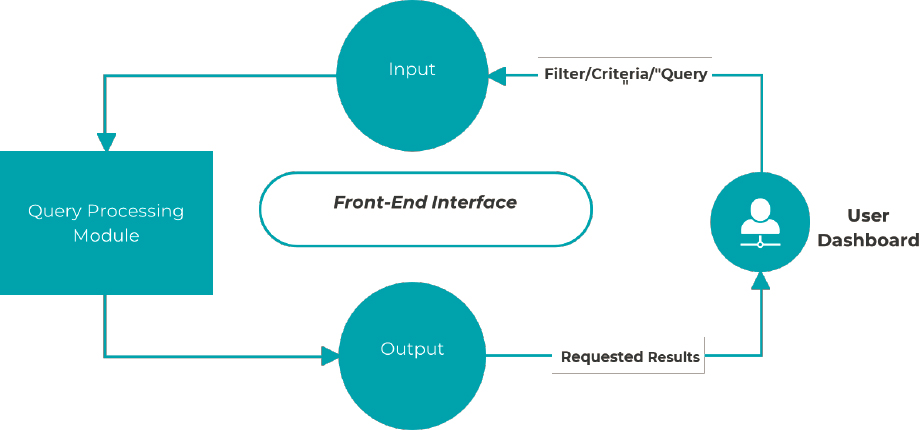

A front-end interface that the user will directly interact with would include the following items to allow the user to query the back-end database (Figure 5-4):

- A web-based user dashboard

- A query processing module

- An application programming interface (API)

In the dashboard, an input link or form accesses the data and allows the user to download and examine the requested data. As an initial check on the accuracy of the data, the data returned to the user will replicate the data used in the 2022 report. The API allows the user to create queries from the back-end database that will produce the required output in the form of spreadsheets, reports, or structured data that can be analyzed in a data analysis system.

Final Product

The final product structurally connects the front-end interface (4) to the back-end database (3) to allow a researcher to create the required queries to provide a more accurate assessment of ongoing efforts to build research capacity and increase the DOD research dollars going to HBCUs, HSIs, TCUs, and other MSIs. Outputs can include datasets based on queries or

SOURCE: Committee-generated.

visual graphics such as a heat map to help decision-makers easily visualize outcomes.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

The committee considered both qualitative and quantitative approaches in closing disparities in research funding and more effectively engaging a diverse range of MSIs in the DOD ecosystem. The Grant Resource-Based Theory of Competitive Advantage suggests a pathway to consider and build upon the unique capabilities of each institution. If DOD PMs are incentivized to build a portfolio of funded efforts, rather than heuristically preferring the larger “known quantities,” the institutions that may be more high-risk, high-reward could become more involved in DOD R&D, to the benefit of all.

Additionally, F&A reimbursement should be set up so as not to create a self-perpetuating cycle in which MSIs struggle to compete for research funding. This limits an MSI’s ability to grow its research programs and negotiate higher F&A rates. Finally, because data collection and analysis is important to set goals and measure progress, a four-step process is suggested for further development.

REFERENCES

Adams, S., and H. Tucker. 2022, February 1. How America cheated its Black colleges. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/susanadams/2022/02/01/for-hbcus-cheated-out-of-billions-bomb-threats-are-latest-indignity/?sh=67df020b640c.

Ahmadi, F., B. Parivizi, and B. Meyhami. 2012. Intellectual capital accounting and its role in creating competitive advantage at the universities. VIRTUAL, 1(1), 894-912. https://sid.ir/paper/660506/en.

Barney, J. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120.

Cheston, D. 2012. Students in space: Universities build a lot of classrooms, but use them infrequently. The John William Pope Center for Higher Education Policy. http://www.popecenter.org/commentaries/article.html?id=2757.

COGR (Council on Governmental Relations). 2019. Excellence in research: The funding model, F&A reimbursement, and why the system works. https://www.cogr.edu/sites/default/files/ExcellenceInResearch4_12_19_0.pdf.

Holdford, D.A. 2018. Resource-based theory of competitive advantage—a framework for pharmacy practice innovation research. Pharmacy Practice (Granada), 16(3).

Janks, G., M. Lockhart, and A.S. Travis. 2012. New metrics for the new normal: Rethinking space utilization within the University System of Georgia. http://search.proquest.com.proxygw.wrlc.org/docview/1519532559/C22AF8746AB48DBPQ/5?accountid=112.

Kahneman, D. 2011. Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Lynch, E. 2015. Innovation management: Implications for management practices for the servant leader in education. Journal of Interdisciplinary Education, 14(1), 40-71.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2022. Defense research capacity at historically black colleges and universities and other minority institutions: Transitioning from good intentions to measurable outcomes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26399.

NSF (National Science Foundation). 2021a. Higher education research and development: Fiscal year 2019. NSF 21-314. National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf21314.

NSF. 2021b. Higher education research and development (HERD) survey 2021. National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. https://ncses.nsf.gov/surveys/higher-education-research-development/2021.

NSF. 2023. R&D expenditures at U.S. universities increased by $8 billion in FY 2022. National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf24307.

University System of Georgia. 2013, July. The University System of Georgia space utilization initiative. http://www.usg.edu/facilities/documents/USG_SpaceUtilizationInitiative_July2013.pdf.

U.S. Federal Register. 2000. Circular A-21: Cost Principles for Educational Institutions. Office of Management and Budget.

U.S. Federal Register. 2014. Title 2: Grants and Agreements. Code of Federal Regulations. 2 CFR Part 200.

Wernerfelt, B. 1984. A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171-180.

Williams, B. 2010. Heuristics and biases in military decision making. Military Review, September-October, 40-52.

This page intentionally left blank.