Understanding and Addressing Misinformation About Science (2025)

Chapter: 8 The Study of Misinformation About Science

8

The Study of Misinformation About Science

In this report so far, we have offered a definition of misinformation about science, examined the contextual factors that shape its dynamics, including various sources and mechanisms of production, spread, and reach; and have discussed what is known from the evidence base about its impacts and the effectiveness of existing interventions. This chapter examines misinformation about science as the subject of a field of study—that is, research about this topic also coheres as a distinct discipline.

An important context here is that the study of misinformation in and of itself extends well beyond science-related topics, and while science is the emphasis of this report, other subjects can often be incorporated in research studies on misinformation about science. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic laid bare the intersections between misinformation about science, crisis, politics, and the media (Ferreira Caceres et al., 2022). Thus, studying misinformation about science often necessitates the study of misinformation more broadly. Throughout this chapter, discussions oscillate between the study of misinformation, generally, and misinformation about topics that relate specifically to science. This is not a mistake but rather is a characteristic of this field of study. To this end, we begin by situating misinformation about science within the multidisciplinary field of misinformation in general. We then review the approaches that are being employed across various disciplines to both understand and address the phenomenon. Finally, we discuss some of the current challenges to research including data limitations, methodological needs, and increased politicization of the topic.

MISINFORMATION: AN EVOLVING, MULTIDISCIPLINARY FIELD OF STUDY

Misinformation as a field of study has been challenged by some who have argued that such a field cannot exist, largely on the grounds that it is too early to investigate misinformation (Avital et al., 2020; Habgood-Coote, 2019), or that “there can’t be a science of misleading content” (Williams, 2024). Concerns regarding the measurement and operationalization of the concept of misinformation are valid; these are ongoing challenges that the field is and will continue to grapple with going forward. However, criticisms of the field based on its origins, primary methods of study, and key findings about impacts hold less merit. Misinformation as an area of inquiry did not begin in response to Brexit or the 2016 U.S. election (Kharazian et al., 2024). The study of misinformation, and particularly misinformation about science, existed before these major events (Lim & Donovan, 2020) and concerns about informational challenges were present during previous pandemics, including the 1918 influenza pandemic, HIV/AIDS, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and many others (Tomes & Parry, 2022).

The field also rests on decades of research on rumors (e.g., Allport & Postman, 1946), propaganda (e.g., Bernays, 1928), and conspiracy theories (e.g., Hofstadter, 1964). Gordon Allport and Leo Postman wrote about rumors, as an object of study, more than half a century ago (Allport & Postman, 1946), and subsequently, Tamotsu Shibutani examined rumors from a sociological perspective, within news environments and crisis events (Shibutani, 1966). Research on propaganda has a long, rich history (Anderson, 2021). Historians have long examined the role that scientific expertise and credentials can play in the inducement of doubt about the connection, for example, between smoking and lung cancer, human activity and global warming, and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) and environmental health (e.g., Michaels, 2006; Michaels & Monforton, 2005; Oreskes & Conway, 2010b). Proctor & Schiebinger (2008) have written about the making and unmaking of ignorance. The field of psychology includes a vast literature addressing the context-relevant elements of belief and attitude formation in the evaluation of information (e.g., Johnson et al., 1993; Petty & Cacioppo, 1986); and philosophers such as Harry Frankfurt have previously addressed “bullshit”—a type of misinformation characterized by complete disregard for truth—head on (Frankfurt, 2005). What may seem contemporary regarding the study of misinformation are actually research questions that have been actively investigated for decades. In other words, the study of misinformation is not new, and misinformation as a multidisciplinary field of study encompasses this rich history of scholarship.

As a multidisciplinary field—one in which multiple disciplines contribute without the blending of methods (van den Besselaar & Heimeriks,

2001)—the evidence base on misinformation reflects the results and methods from a number of long-standing disciplines, including anthropology, communication studies, computer science, engineering, history, law, political science, psychology, science and technology studies, and sociology. Furthermore, an argument could be made that a new interdisciplinary field is emerging, where there is a blending of methods, new frameworks, new syntheses, and new research collaborations that can be exceptionally useful across topics and disciplines.

In the last decade, the field has seen new and increased scholarly attention toward misinformation on social media platforms in particular. Between 2006 and 2023, there have been nearly 30,000 published articles that have used the old Twitter application programming interface (API) to collect and analyze social media user data (Murtfeldt, 2024). The broad access to data on Twitter during this period also means that an outsized number of studies reflect research conducted using Twitter data. Many of the topics from the top most-cited articles of this pool reflect issues that are germane to misinformation, such as understanding the factors that influence the spread of true and false information, assessing the credibility of information across news sources, understanding scientific misunderstandings from commercial advertising, and assessing AI capabilities for detecting false news (Murtfeldt, 2024). However, with the recent changes around data access at X (formerly Twitter), the number of research projects engaging with social media data has dropped dramatically (Murtfeldt, 2024), and as a result, some groups have moved to conducting studies on other social media platforms. That said, continual changes in data access will likely also shape what can be known about misinformation in the context of social media environments (see the section later in this chapter on “Challenges of obtaining high-quality data from social media contexts”). Importantly, there is a critical need to distribute the field’s attention across other forms of media, including radio, television, and podcasts (see Chapter 4).

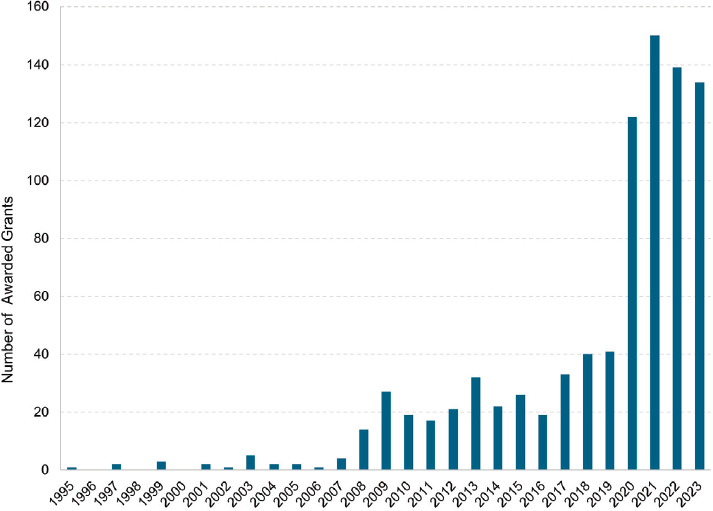

Overall, there has been an increase in the number of publications related to misinformation. For example, as of August 8, 2024, a search on Web of Science (Core Collection)1 yields nearly 9,000 articles that have been published since 2020 with the term “misinformation” in either the title, abstract, or as part of the keywords. We note that this is likely an underestimate of the total number of articles published about the topic, given our understanding that “misinformation” is only one term that captures this field of research. Nevertheless, it is clear that scholarly attention on the subject has grown dramatically in recent years, and is perhaps linked

___________________

1 Web of Science (Core Collection) is an online, paid-access platform that provides reference and citation data from academic journals, conference proceedings, and other documents in various academic disciplines.

to increases in funding support for proposed projects on misinformation (Figure 8-1).

For understanding misinformation about science specifically, it is important to distinguish between studying misinformation in science (or, research that in some way does not adhere to the shared principles and assumptions of scientific inquiry: reproducibility, generalizability, collectivity, uncertainty, and refinement; see Chapter 2) and about science (or, information on science- and health-related topics that in some way diverges from the interpretation based on accepted scientific evidence). Most researchers focus on the latter, while a smaller group of researchers are focused on topics related to misinformation in science, such as the rise in predatory journals (Bartholomew, 2014), agnotology (i.e., the study of how doubt or ignorance are created around a topic as a result of the publication of inaccurate or misleading results; Bedford, 2010; Proctor & Schiebinger,

SOURCE: Committee generated using all awarded grant data provided by Clarivate’s Web of Science Grant Index1 (retrieved on August 8, 2024).

___________________

1 Clarivate’s Grant Index is an online resource as part of the Web of Science platform that provides paid access to standardized data for awarded grants from 400+ funding agencies around the globe.

2008), reputation laundering (Bergstrom & West, 2023), and scientific fraud (Crocker, 2011). In the view of this committee, both aspects are important for obtaining a comprehensive understanding of the problem of misinformation as it relates to science and establishing approaches to strengthen the institution of science and public trust in science.

METHODOLOGICAL APPROACHES FOR STUDYING MISINFORMATION ABOUT SCIENCE

The many disciplines incorporated in the study of misinformation about science, bring a diversity of qualitative and quantitative research methods including experiments (Pennycook et al., 2021), surveys (Roozenbeek et al., 2020), interviews (Malhotra et al., 2023), digital ethnography (Haughey et al., 2022), computational approaches (Ferrara et al., 2020; Shao et al., 2016) and design science research (Hevner, 2004; Krafft & Donovan, 2020; Simon, 1988; Young et al., 2021). These various research methods have been employed to measure the spread of misinformation on social media (Del Vicario et al., 2016), test receptivity to misinformation and theories of motivated reasoning and confirmation bias (Zhou & Shen, 2022), evaluate the impact of misinformation on trust and political attitudes (Tucker et al., 2018; van der Linden et al., 2020), develop automated methods to detecting and interrupting the flow of misinformation (Shu et al., 2017), design new interfaces that promote healthy democratic discourse (Young et al., 2021), and inspire new policies of intervention (Calo et al., 2021).

More recent data collection efforts have largely been focused on vaccine misinformation, COVID-19 misinformation, and misinformation about climate change (Murphy et al., 2023). The data sets are typically large-scale social media data from either X or Facebook, with researchers using X more frequently because of its past policy that provided more access to its data.

Additionally, the research methods employed to study misinformation about science are almost identical to the methods employed to study other topics. In fact, many researchers studying the spread of misinformation and disinformation during U.S. elections also study misinformation about vaccines. Methods likewise are cross-disciplinary and nominally topic-agnostic, and this crossover is due, in part, to the significant overlap between the skillsets required to develop tools for studying misinformation of all types. For example, surveys can be designed to incorporate a question about hydroxychloroquine or one about voting intention. Cognitive assessments can be included in experiments about measles vaccines or about trust in the media. Computational sociologists can collect and analyze a collection of tweets about COVID-19 or a collection about the Boston Marathon bombing. Historians of science can study the role of corporate actors around

climate change or corporate actors around smoking. That said, while social science methods are common and can be deployed to study misinformation in a variety of realms, there are also differences when they are applied to the study of misinformation about science. For example, studying misinformation about science requires some degree of scientific expertise in the subject matter being studied in order to make a determination regarding the weight of the accepted scientific evidence. In this case, the appropriation of methods from another domain to the study of misinformation about science might require that additional nuances be considered (see Chapter 2).

The application of qualitative methods, in particular, to the study of misinformation about science facilitate understanding of the role of context and nuance that complement quantitative research findings (Polleri, 2022; Teplinsky et al., 2022). This suite of methods (e.g., ethnography, interviews, focus groups, content analysis, discourse analysis) can also shed light on otherwise invisible aspects of misinformation about science (Roller, 2022), and become essential in the face of limited access to data from technology platforms that makes quantification a challenge (Bandy, 2021; Schellewald 2021). Qualitative research may also be particularly useful for understanding the different ways that information can be distorted as it traverses the 21st century information ecosystem, thus facilitating later quantification of information that appears in each category. Moreover, qualitative methodologies also played an important role in guiding public health response to questions and concerns about COVID-19 vaccines that emerged due to misinformation (see Box 8-1).

By nature, qualitative work does not always easily fit into the same discussions and dominant paradigms that quantitative work speaks to more directly. For example, debates about the amount (i.e., prevalence) of misinformation or how to categorize various types of it, which are common in quantitative studies, are less of the focus of qualitative research. Robust qualitative research and quantitative research are complementary to each other, and the intertwining of observational and experimental evidence is crucial for understanding causal inference on human behavior (Bailey et al., 2024; Greenhalgh, 2020; Greenhalgh et al., 2022). However, while qualitative research contributes significant insights to the understanding of misinformation about science, relatively little of this work is routinely brought into conversation with quantitative research on misinformation.

METHODOLOGICAL APPROACHES FOR ADDRESSING MISINFORMATION ABOUT SCIENCE

The potential negative impacts associated with misinformation about science are complex (see Chapter 6) and necessitate responses that can address this complexity. Several uptake-based interventions show promise for

immediate implementation: there is moderate-to-strong evidence supporting the efficacy of remedies such as prebunking, debunking, lateral reading, and digital media literacy tips in helping individuals recognize and/or reduce the sharing of misinformation about science online (see Chapter 7). These techniques have therefore earned a place in the suite of tools to address the spread of misinformation about science in online contexts.

The most widely tested interventions to address misinformation are rooted in methodological individualism and are amenable to experimental research given existing tools. Individuals can be recruited to participate in

randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in a laboratory or online setting where they are exposed to carefully selected stimuli that are intended to be representative of misinformation about science that individuals might actually encounter online. These individuals’ behaviors, intentions, attitudes, and beliefs can be indexed using well-designed psychometric instruments. While this research on interventions is robust and dynamic and has established the existence of several effective remedies, it is also true that effects are small and durability of the effects are questionable. Methodologies that focus on individuals also raises questions about how best to study interventions and effects at the group or institution level (Chater & Loewenstein, 2023).

OVERARCHING CHALLENGES TO STUDYING AND ADDRESSING MISINFORMATION ABOUT SCIENCE

Despite the advancements made in the study of misinformation about science, challenges remain. This section discusses some of these challenges within three broad categories: (a) defining, conceptualizing, and theorizing about misinformation about science and its mitigation; (b) methodological and data limitations across different contexts, populations, and groups; and (c) occupational health and safety of researchers.

Challenges of Conceptualization and Definition

One of the more fundamental challenges to studying misinformation is how to define and operationalize it, including how inaccurate a claim must be before it is labeled as misinformation. Moreover, as previously mentioned in this report (see Chapter 2), there is some disagreement in the field regarding whether certain informational phenomena constitute misinformation and the importance of intentionality within the definition (Altay et al., 2023). This lack of conceptual clarity may be a byproduct of the rapid expansion of the field of misinformation research since 2016, as well as the nature of the scholarship in this arena, in which studies are designed, planned, and conducted within different disciplinary silos with little cross-fertilization (Broda & Strömbäck, 2024). Nevertheless, clear, widely shared, and context-specific definitions of misinformation are critical for studying this phenomenon in ways that yield effective results and underpin disciplinary coherence. Additionally, such agreement helps to establish a legitimate basis for intervention. In the absence of such shared definitions and operationalizations across channels and media types, choosing the most appropriate and efficacious set of tools for measurement or for intervening becomes highly challenging.

Another challenge for studying misinformation is establishing the appropriate unit of analysis. Misinformation, as addressed in research

literature, appears as a phenomenon that exists at a range of units of analysis (i.e., aggregations), from the individual to the massively cumulative (Southwell et al., 2022). While studies have often focused on the wide-ranging effects of single, specific instances of false information, the contemporary concern about misinformation among scholars, policymakers and interested groups is not primarily about disconnected, errant claims about science, or these “atoms of content” (Wardle, 2023). Rather, current concern in both the academic and public arenas tends to center on the effects of larger streams of information, whether through viral, emergent spread among true believers, or coordinated efforts by knowing actors (disinformation). There has been a recent push to move away from the single, specific instance as the focal point of research to broader units that allow for wider perspectives. For example, to evaluate the effects of a single claim questioning the harm of cigarette smoking by the tobacco industry, circa 1975, is to miss the potentially multiplicative effects of decades of multichannel and multitarget efforts by the industry (see Chapter 4). The impact of considering units of analysis for understanding the nature of misinformation is also illuminated in a more contemporary example. A blog post may contain false statements about a treatment for a disease. While individual statements in the post may be classified as misinformation, could an entire post be classified as such? If the blog habitually disseminates such false assertions, how should it be described? Similarly, what term should be used to describe how this one blog may be part of a network of similar blogs with similar claims?

Some broader units of analysis appearing in contemporary research include source-based classifications of misinformation, which involves categorizing information coming from particular sources and web domains based on the reliability of the source (Cordonier & Brest, 2021; Grinberg et al., 2019), and narrative-based classifications of misinformation, where, by taking true information out of context and aggregating it in specific ways (e.g., clipping livestreams, selectively sharing scientific preprints), actors can promote “inaccurate narratives” (Wardle, 2023). The factually correct, but potentially misleading aforementioned Washington Post headline, “Vaccinated people now make up a majority of COVID deaths,” is an example of the latter, in a case where a news article from reputable sources was used to amplify misinformation narratives (see Chapter 2; Beard, 2022; Goel et al., 2023). Thus, the fact that misinformation exists as various units—some of which are difficult to measure—presents a challenge to establishing an accurate understanding of the phenomenon, including, as discussed above, the lines around what is and is not misinformation in any given context, and the wide range of impacts it has. Agreement in the field on this component is also important for the purposes of measurement and guiding interventions.

Challenges in Theorizing About Intervention Effects

Another major challenge of studying misinformation about science lies in showing why interventions are effective. Despite the rapid, explosive growth in both academic and industry research on interventions to address misinformation in recent years, there remain large gaps in the collective understanding of the real-world efficacy of many of the approaches that have been proposed, developed, and implemented. Many tools that appear to be efficacious in small-scale, controlled experiments do not appear to fare well in real-world settings (Nordon et al., 2016). Researchers has struggled to identify why this is the case; however, one aspect of this efficacy gap is that many interventions may be relatively effective at addressing certain aspects of the broader problem (e.g., reducing spread of viral misinformation) but ineffective with respect to the most consequential outcomes of interest (e.g., the formation of misbeliefs with the potential to negatively affect real-world decision making). Despite extensive replication of a small number of effects, the implications of the underlying theoretical mechanism(s) have not been tested as rigorously. In other words, although a specific effect may replicate several times in a laboratory setting, rote replication alone is insufficient to predict generalizability outside the experimental context. To achieve such generalizability, a clear theoretical mechanism is needed to explain why a particular intervention is effective, and to make predictions about the specific contexts under which replication can be expected.

Some of the most generalizable interventions that do exist are rooted in such mechanisms. For example, prebunking is rooted in inoculation theory (Cook et al., 2017), and accuracy nudge interventions are rooted in dual-process theories of human cognition (Pennycook & Rand, 2021). However, in practice, experiments differ in the degree to which they test the underlying theoretical mechanisms, for example, the uptake of misinformation about science. Even more limited are critical tests that enable scientists to determine which of several possible theoretical explanations are most scientifically parsimonious by facilitating the explanation of several different effects with as few theoretical assumptions as possible (e.g., Pennycook & Rand, 2019, who designed an experiment to adjudicate between dual-process and motivated reasoning explanations for misinformation sharing). Such critical tests of theoretical mechanisms contribute to a cohesive research program, resulting in a contribution to generalizable scientific knowledge.

An emerging body of scholarship has begun to review existing empirical evidence and link that evidence to promising theories (e.g., expectancy value theory, dual-process theory, and fuzzy-trace theory). For example, the target article of a Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition (JARMAC) special issue reviewed the evidence on different theoretical

explanations for why misinformation about COVID-19 might be compelling and implications for risky decision making (Reyna et al., 2021). But despite significant evidence in analogous fields (e.g., medical decision making), approaches to testing interventions for addressing misinformation about science still remain largely focused on testing specific experimental effects, with comparatively little theoretical justification. Thus, it remains to be determined why specific interventions work, what might be driving effect sizes, and in what contexts they will be ineffective. Moreover, research to advance understanding of misinformation about science would also benefit from deeper engagement with a broad set of theoretical perspectives from other disciplines such as the behavioral and decision sciences.

Challenges of Scaling Up Interventions

Closely tied to the issue of efficacy is the challenge of scaling up and broadly disseminating many of the proposed interventions aimed at addressing misinformation that are coming out of academic and industry research. It is unknown whether interventions that have positive impacts at the individual level are useful for countering community- and societal-level consequences of widespread misinformation about science in the information ecosystem. This is in large part because they simply are too onerous to deploy at the massive scale needed. In addition, interventions are often more effective when targeted for a given context and require collaboration and refinement with the target population. There is moderate evidence that some platform-level interventions (e.g., deplatforming) are effective for reducing volumes of harmful content (Chandrasekharan, 2017; Jhaver et al., 2021; Saleem & Ruths, 2018; Thomas & Wahedi, 2023); however, even these effects may simply be “drops in the bucket” given the rapid proliferation of tools (e.g., large language models) for spreading information, including misinformation. Here again, a theoretical understanding of why misinformation spreads could lead to significant resource savings, and absent such a mechanism, the expense required to test the efficacy of interventions at scale may be prohibitive.

The pace of scientific publishing is also too slow to conduct experimental tests each time a new type of misinformation appears. For example, if we assume that misinformation about the COVID-19 pandemic is fundamentally different from misinformation about future pandemics, then requiring extensive experimental testing prior to deploying interventions could result in that misinformation causing irreversible damage and harm in the interim. Encouragingly, the evidence base in science is cumulative; therefore, theoretically-motivated approaches can inform preliminary responses while empirical work is being conducted. Indeed, the very purpose of scientific theory is to make predictions based upon empirical regularities

that can extend to novel settings. Thus, a clear understanding of theoretical mechanisms can support proactive responses to new sources of misinformation about science.

The very nature of the research conducted also poses challenges to scaling up interventions. As stated above, a majority of studies surrounding interventions to address misinformation are rooted in methodological individualism. In other words, the unit of analysis is the individual decision maker, and interventions are designed to target individuals at the time decisions are made. These studies, by design, randomize across cultural, social, and community-based contexts, and therefore a single study may not take all of these important social factors into account. Similarly, questions about the influences of different technological affordances are typically outside the scope of these studies. Thus, there is a dearth of scholarship on evidence-based strategies for addressing misinformation that explicitly take into account relevant social, cultural, and technological factors, especially at the level of specific communities.

Finally, it is worth briefly mentioning that current funding models have also played a role in shaping the existing scholarship on interventions for addressing misinformation. For example, the scope of work reflected in requests for proposals (RFPs) have dictated where attention and resources in the field are directed. This means that if funding priorities consistently emphasize research needs around individual-level solutions (Chater & Loewenstein, 2023), then gaps will remain in understanding the nature of the problem and potential solutions at higher levels and larger scales (e.g., community-based, platform and platform design-based, policy, and regulatory approaches).

Challenges of Obtaining High-Quality Data from Social Media Contexts

Another issue hampering research in this area is lack of access to certain kinds of quantitative data that would greatly elucidate how misinformation about science originates and spreads on social media, one of the major spaces within which misinformation now propagates. Historically, many social media companies made at least some public data available through APIs, which provided machine-readable data in bulk for researchers and corporate partners alike, and in some cases, free of charge. However, in recent years, some of the most useful APIs for researchers have been eliminated or made prohibitively expensive by their parent companies (Ledford, 2023; Pequeño IV, 2023; van der Vlist et al., 2022). These decisions have had several downstream effects, most notably a reduction in research on the platforms in question but have also created conditions in which researchers have had to develop unsanctioned methods of collecting data automatically, a process known as scraping (Trezza, 2023). While it may be the only option for collecting certain kinds of data, scraping is not ideal because of

the inconsistency of the data it provides as well as the potential legal risks to which it may expose its practitioners (Luscombe et al., 2022).

Obtaining access to social media data may be especially challenging for researchers at lesser-resourced institutions or those without sufficient external funding. The decision by the platforms to charge for access to data also shifts the power in determining what topics can be studied using social media data from researchers to funders of research (both internal and external). Other data access models, such as TikTok’s, still do not require payment for its data, but are limited to researchers in the United States and Europe. Additionally, qualifying researchers are required to submit project proposals when applying for access, and TikTok reserves the right to reject proposals at will.

After adopting multiple data access systems over the years, including APIs and invite-only research projects, in 2023 Meta introduced a novel system that could serve as an industry model. It now provides access to data through remotely-managed “clean rooms” in which all analyses must be conducted—thus, no raw data can be downloaded locally, only aggregate statistics and models. Similar to TikTok, researchers must apply to access the data, but applications are processed and evaluated by the University of Michigan’s Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR),2 meaning that Meta has no prerogative to veto projects that may cast them in a negative light. At the time of this consensus report, this initiative is in its infancy, but attempts to strike a balance between maximizing both user privacy and researchers’ access to data at scale.

Even when APIs were more plentiful than they are now, the data they provided were limited in both scale and scope, and substantial inconsistencies in the kinds of data provided by different platforms impeded multiplatform research. Some APIs, such as Twitter’s, Facebook’s, and Reddit’s, included data about sharing and reactions (“likes,” “favorites,” and similar affordances), but not other types of information such as how many times a post was viewed, clicked on, or otherwise interacted with. Another point worth noting is that while these data provided information on what is being posted, they did not necessarily reflect real-world exposure and attention to this information (Lazer, 2020). At the same time, both the user interfaces and APIs of video-sharing sites including YouTube and TikTok featured view (but not engagement) counts.

Thus, the ability to answer as simple a question as how many times a given piece of misinformation about science has been viewed online depends on arbitrary decisions by the parent company. This issue is exacerbated by the fact that many of these metrics, in turn, might be gamed (whereby many of the actors that are circulating misinformation, in

___________________

2 Social Media Archive @ICPSR. Available at https://socialmediaarchive.org

turn, might seek to manipulate indicators of how widely circulated a piece of information was). Therefore, researchers studying multiple platforms—a long-recommended best practice for social media research—contend with incommensurate data from companies that have made different decisions, and consequently are not adequately able to understand, for example, how misinformation travels between platforms. Without industry standards and/or governmental policies to impose consistency with respect to the provision of data, multi-platform research on misinformation will likely continue to be rare and limited.

Finally, even at its best, social media contexts are not sufficient for studying misinformation about science or even other topics. The substantial amount of research on misinformation based on social media data makes this point worth reiterating. Moreover, even though social media contexts are currently the dominant focus of most misinformation research, the field is still unable to approximate what fraction of exposure to misinformation is from social media. Not everyone is an active social media user, and even for those who are, social media does not necessarily account for the full scope of their exposure to misinformation. Within specific platforms, some users may be more visible than others: for example, those who participate in hashtag campaigns or who use certain keywords may be better represented in study samples than those who do not. Studies based on platforms used by most of a given population, such as Facebook with U.S. adults, still cannot effectively generalize to offline target populations because behavior may be platform-specific. In other words, research on misinformation about science that is based on Facebook data can reveal how people engage with such misinformation on Facebook, but these findings may not be generalizable to other platforms like X and Reddit, or even to non-social media contexts (e.g., TV, radio, podcast, private messaging apps, face to face). Importantly, studies on social media that require users to opt in, such as experiments, may also suffer from selection bias: people who are least trusting of conventional authorities such as mainstream news are more likely to believe misinformation (Zimmermann & Kohring, 2020), but they may also be less likely to participate in such research. Moreover, even those who choose to opt in may change their behavior to appear more socially acceptable, given that people know that consuming certain kinds of misinformation may reflect poorly on them (Yang & Horning, 2020).

Challenges of Obtaining Comprehensive Data Across Populations: Data Absenteeism

The study of misinformation about science is also beset by data absenteeism, which is defined as the “absence of data […] from groups experiencing social vulnerability” (Viswanath et al., 2022c, p. 209). Historically, this has

included, among others, non-White racial groups, sexual and gender minorities, lower-income immigrants, people with disabilities, and those who live in geographically remote locations. Data absenteeism manifests differently across methods. In surveys and experiments that rely on participant recruitment (e.g., clinical trials), it can arise due to issues such as the amount of compensation offered; the quality, locations, and numbers of study advertisements; the requirement to take time from work to participate; and historical distrust between the scientific community and minoritized community groups. Additionally, standard survey research design practices such as probability sampling, limited callbacks, and recruitment costs could limit data collection from a more representative population. Social factors—including stigma, racism, legal status, competing demands, lack of reliable transportation, and challenges with childcare, among others—may also make it difficult for some individuals (e.g., those from low socio-economic positions) to participate in misinformation research (George et al., 2014; Nagler et al., 2013; Viswanath et al., 2022c).

For observational studies, like those based on social media trace data, data absenteeism manifests as differences between the general population and the user base of the platform in question. In other words, participation on certain social media platforms, especially those that are usually relied on for research such as X or Facebook may not be representative of the general population, thus denying a voice to certain groups (Viswanath et al., 2024). The user base on X, for example, has historically had an overrepresentation of young people (Auxier & Anderson, 2021; Cox, 2024). Furthermore, globally as well as domestically, what is known about misinformation about science is likely biased toward western, educated, industrial, rich, democratic populations (Henrich et al., 2010), while little is known about how the levels of exposure and impacts of misinformation about science might differ among non-Western populations.

For any science communication research that assesses the audiences, the lack of participation by some groups can be compounded by standard approaches often used to gather data (Lee & Viswanath, 2020; Viswanath et al., 2022c), and while the reasons for this are varied, all of them are addressable. Cyberinfrastructure, which is often relied upon for data collection may be poor in underserved areas, making it difficult to collect data. For example, poor communication infrastructure remains a persistent problem in rural areas, poorer neighborhoods in cities, and in lower-income countries (Viswanath et al., 2022a; Whitacre et al., 2015). Additionally, frequent interruptions in telecommunication services, such as cellphone disconnections, could preclude data collection from some groups. Likewise, digital devices are often major tools for data collection, yet the continuing digital divide among different groups could preclude participation in misinformation research.

Clearly, data absenteeism is a significant challenge, and confidence in results and ensuing inferences from studies that suffer from it leads to data chauvinism (i.e., faith in the size of data without considerations for quality and contexts) and misleading generalizations (Lee & Viswanath, 2020). The refrain that underserved groups are “hard to reach” is also misleading given they are “hardly reached,” thereby straining the reliability of misinformation research (Viswanath et al., 2022c). These phenomena require even more critical attention in the era of “big data” when the effects of science infodemics and the ways to address them grow more urgent. While it may require more work to incorporate historically excluded people into misinformation research studies, an incomplete understanding of this topic will persist without doing so.

Challenges of Study Design

Research design is particularly germane when evaluating the effects or the lack of effects of misinformation beyond the individual level and in understanding the impact of misinformation on underserved groups such as those from lower socio-economic status and minoritized communities. Causal relationships between exposure and effects are most studied using RCTs or lab or field experiments where there is greater control between exposure to stimulus (bits of misinformation about science) and effects such as the development or reinforcement of inaccurate science knowledge and misbeliefs, that in turn, can influence attitudes and behaviors (e.g., denial of climate change or vaccine hesitance). RCTs are not without limitations and caveats (Bailey et al., 2024; Greenhalgh et al., 2022):

- Real-world conditions can hardly be replicated in experimental contexts given there is a multiplicity of influences that interact with exposure to misinformation leading to certain effects.

- The act of exposing people to misinformation, on purpose, could be viewed as unethical though it is often acceptable practice in deception studies in the context of psychological research when followed by debrief (Boynton et al., 2013).

- More critically, few RCTs and experiments include members from historically underserved groups (e.g., communities of color, low-income communities, rural communities; Kwon et al., 2024).

On the latter point, medical mistrust among Black communities has certainly been shaped by past atrocities at the hand of science and medical institutions (e.g., unethical gynecological surgeries performed by J. Marion Sims on three Black women slaves, the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis on Black men, and the unethical collection of human cells from

Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman, for medical research; Bajaj & Stanford, 2021; Beskow, 2016; Wall, 2006). Yet, historical patterns of mistrust only partially explain the absence of Black Americans from research studies. Contemporary realities, particularly structural racism, continue to plague these communities (Bailey, 2024), and other factors have been identified as explanations for the lack of participation of Black Americans in clinical trials: lack of awareness about trials, economic factors, and communication issues (Harris et al., 1996). The extent to which these same factors may similarly influence the participation of Black Americans in science communication (including misinformation) studies requires deeper exploration.

Challenges of Researcher’s Health and Safety

As discussed previously in this report, some scientific issues have become politicized over time (Druckman, 2022), and this reality can make studying misinformation about such topics challenging in ways that go beyond the standard challenges of gathering data, running analyses, and interpreting results. For many researchers studying misinformation, the challenges could also include Freedom of Information Act requests, lawsuits, subpoenas, online abuse, and other forms of intimidation and harassment (Quinn, 2023). Such incidents have led some researchers and universities to either discontinue or at least reduce research focused on tracking online misinformation—commonly characterized as a “chilling effect” on scholarship (Quinn, 2023). Researchers have just begun to talk about this publicly (Starbird, 2023), but many have spoken anonymously for fear of reprisal. To this end, additional safeguards may be needed at research institutions and universities to specifically support researchers at all levels (including graduate and postdoctoral levels) who study misinformation. In the past, climate change researchers have faced similar challenges (Levinson-Waldman, 2011), so there may be lessons to be learned from this arena for those studying misinformation of all types. But the potential to quell inquiry goes beyond the individual researchers in the spotlight. In light of the additional foreseen challenges, graduate students may choose different research directions, and universities may be less likely to make long-term investments in this research area, given it may result in increased legal fees.

Researchers studying misinformation about science are also exposed to potentially violent and graphic content on the internet, including hate speech and imagery and videos during violent conflicts, which can negatively impact their psychological well-being (Holman et al., 2024; Pluta, 2023; Steiger et al., 2021). Additionally, some systematic disinformation campaigns do not exist in a vacuum (Kuo & Marwick, 2021) and are linked in ways that may, for example, connect a researcher studying vaccine misinformation to the latest QAnon conspiracy theory. The impact on

mental health of researchers studying misinformation on a daily basis is unknown and worth more empirical scrutiny. One might be able to draw lessons from other professions such as healthcare and clinical medicine where burnout and other threats to mental well-being are not uncommon (National Academies, 2019b; Office of the Surgeon General, 2022).

SUMMARY

It is clear that there has been long-standing scholarly attention dedicated to understanding the nature of different types of false information (e.g., rumors, misinformation, propaganda). Such efforts reflect the interest of multiple disciplines, including communication studies, computer science, engineering, history, law, political science, psychology, science and technology studies, sociology, among others, and has resulted in the development of a suite of methods and tools to both study these phenomena and intervene to mitigate negative impacts. In recent years, discourse on misinformation has become widespread in the public arena. At the same time, building a robust evidence base that documents the prevalence, spread, exposure, and effects has been challenging. The challenges in studying misinformation about science are manifold and include inconsistent and evolving definitions of what constitutes as misinformation; lack of access to data on social media platforms and connecting them to the larger information ecosystem; study designs that can provide confidence in causal inference between exposure and outcomes; and data absenteeism. As it relates to misinformation about science specifically, there has also been uneven scholarly attention toward understanding the nature of the phenomenon across science topics (e.g., vaccines vs. women’s health issues) as well as the challenges associated with studying highly politicized topics. These challenges are not insurmountable, and responding to these challenges has the potential to lead to new and informative research directions for the field.

Conclusion 8-1: There has been considerable emphasis on studying misinformation about science and potential solutions at the individual level. In contrast, there has been limited emphasis on understanding the phenomenon of misinformation at higher levels and larger scales, which may inadvertently place the onus on the individual to mitigate the problem. There has been limited progress on:

- Understanding how structural and contextual factors such as social class, race/ethnicity, culture, and geography, and social networks and institutions influence the origin, spread, and impact of misinformation about science.

- Understanding how other important factors (i.e., social, political, and technological forces) that shape the information

- environment interact with misinformation about science to influence decision making and well-being.

- Understanding the larger impact that systematic disinformation campaigns can have and how to effectively intervene to counter misinformation about science from such sources.

- Understanding the effectiveness of existing approaches to address misinformation about science, either alone or in combination, with an eye toward better design, selection, and implementation.

Conclusion 8-2: Some progress has been made on understanding the nature of misinformation on select social media platforms; however, a comprehensive picture across all major platforms is lacking. The ability to detect and study misinformation about science on social media platforms is currently limited by inconsistent rules for data access, cost-prohibitive data restrictions, and privacy concerns.

This page intentionally left blank.