Understanding and Addressing Misinformation About Science (2025)

Chapter: 7 Intervening to Address Misinformation About Science

7

Intervening to Address Misinformation About Science

As described in earlier chapters of this report, misinformation about science can be consequential for society in many ways, including potentially distorting public perceptions of personal, ecological, and societal risks; disrupting agency for individual and collective decision making across a wide array of critical issues; and disrupting societal stability. Intentional, strategic, and evidence-based efforts to address these and other negative impacts on individuals, communities, and humanity (as well as other species on the planet) offer potential solutions for effectively mitigating such impacts. Over the course of this chapter, the committee presents an overview of such efforts to date—efforts that have been undertaken by a wide range of actors across myriad issues. Alongside this, the chapter includes a framework for organizing this diverse, multidisciplinary, multi-sector domain of scholarship, practice, and policymaking. Throughout, we refer to intentional efforts with the explicit goal of addressing one or more (perceived) consequences of misinformation about science as interventions. This chapter begins with a brief history of interventions aimed at addressing misinformation about science followed by a discussion of interventions that are currently in use and the evidence for their effectiveness.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INTERVENING TO ADDRESS MISINFORMATION ABOUT SCIENCE

Historical efforts to address misinformation about science in the United States can be clearly seen within the country’s broader history of mass media. Since the advent of various mass media in the United States, the

occasional publication of misleading information about science has raised concern from scientists, public officials, and observers. For example, during the American Revolutionary War, General George Washington’s smallpox inoculation orders faced headwinds of opposition in the form of pamphlets and erroneous claims (Wehrman, 2022). In the 19th century, long before the advent of electronic media, demonstrably false claims about science also appeared in print news publications. In 1869, for example, newspapers in the northeastern United States such as the Syracuse Standard featured stories warning about a supposedly deadly caterpillar, the tomato hornworm, despite a body of entomology research that discounted any fatal threat to human beings (O’Connor & Weatherall, 2019).

Sometimes concern over such false claims has led to policy initiatives and interventions to mitigate the impacts of such content, and over time, some institutions and professional organizations in the United States have developed efforts to address inaccuracies in media content. Examples of this include the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Bad Ad program regarding pharmaceutical advertising (O’Donoghue et al., 2015) and fact-checking initiatives run by the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania (Amazeen, 2020; Young et al., 2018). However, the appearance of false claims in media outlets has not always been met with immediate institutional response, and the story of formal organizational efforts to mitigate misinformation through intervention has been a complex and iterative one that only in recent years has included peer-reviewed evaluation of such efforts, for example, Aikin et al. (2015), Ecker et al. (2022), and Kozyreva et al. (2024).

Despite individual complaints about the publication of falsehoods in newspapers and other print publications, formal calls among professional journalism associations to avoid spreading falsehoods did not emerge prominently until the late 19th century and early 20th century (Ward, 2010). Moreover, these initial efforts to address misinformation in journalism took multiple forms. An exhaustive journalism textbook intended to educate professional journalists about the missteps of false claims, Steps into Journalism, by Chicago Tribune literary editor Edwin Shuman (1894), emphasized the obligation of the reporter to “reproduce facts” (Ward, 2010, p. 141). In 1923, the American Society of News Editors, and in 1926, the professional journalists’ association Sigma Delta Chi (which later would become the Society of Professional Journalists), formally proposed codes of ethics that emphasized objectivity and truthfulness, which led to a widely adopted professional code of U.S. journalists that explicitly emphasized the need to seek truth and report it (Ward, 2010). In 1934, nearly a dozen journalists founded the National Association of Science Writers “to foster the dissemination of accurate scientific knowledge” (Barton, 1934, p. 386). The association’s emphasis on publishing science content intended

for public audiences, in part, reflected decades of advocacy by some leaders in the American educational system to develop science curricula in U.S. schools to help promote public understanding and acceptance of innovations in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. While these formal attempts to establish a code of ethics among professional journalism organizations are imperative for the field when addressing misinformation, it should be noted that there is still some difficulty in the journalism field contending with inaccuracies in modern news coverage (see Chapter 4 for more details).

Alongside professional codes from associations, federal government actors in the early 20th century also acted to thwart the potential effects of misinformation in service of product promotion, namely claims about the efficacy and safety of medicines and foods that were not supported by scientific research. Consider the case of so-called patent medicines like snake oil liniment and other elixirs that were prominently marketed to consumers in the United States from the mid-19th century through the early 20th century (Jaafar et al., 2021). Despite the phrase “patent medicine” that was sometimes used to describe such products, typically these products had not been formally patented under U.S. law and did not include accurate and exhaustive labeling of ingredients. Rattlesnake Bill’s Oil, for example, was manufactured in Belleville, New Jersey; however, rattlesnakes were not typical in New Jersey at the time (Jaafar et al., 2021). Popular concern about such products encouraged the enactment of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 (Denham, 2020; Jaafar et al., 2021). That act set the stage for the development of what would later become the FDA, which gained authority to oversee the safety of food, drugs, medical devices, and cosmetics in 1938.

Public concern over false or misleading labeling of products led to support for the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, but this policy primarily focused on claims about the ingredients in products rather than claims about the benefits of said products (Denham, 2020). Since then, regulatory oversight of misinformation about medicines and food has evolved through a series of iterations and policy debates. But not all health-related products are treated equally in the United States. Whereas medicines must be approved by the FDA before they can be sold or marketed, dietary supplements currently do not require such approval (see U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2022). The regulation of claims has also been nuanced in terms of the exact message content in question.

The iteration of regulatory considerations for food and drug claims (e.g., eventual consideration of claims about product benefits and not just claims about the ingredients in a bottle) suggests increased acknowledgement over time by regulators that misinformation can include different components or elements of claims as well as various formats of accompanying

material. In other words, policymakers have come to acknowledge that misinformation is not a monolithic entity present in uniform doses in the information ecosystem, but rather a collection of different possibilities for error and deception (only some of which have sparked sufficient public concern to inspire attention). Moreover, the U.S. experience of regulating the advertising of medicines and food highlights a tension that interventions to address misinformation have continued to face in the 21st century: characterizing claims as false or misleading depends on the existence of a formally recognized, scientific evidence base against which these inaccurate claims contrast. This presents a challenge that extends to many different claims involving science: if the respective scientific research does not exist yet, claim accuracy is difficult to define and therefore poses challenges for mitigation.

In the latter half of the 20th century, U.S. governmental regulation of false claims about certain food and drugs evolved to include corrective efforts to address misinformation in instances where clear contrasts between product claims and existing scientific evidence existed. This emphasis on corrective advertising acknowledged the possibility of intervening with audience members directly to address misbeliefs due to exposure to misinformation, reflecting a different type of intervention than restricting actors from publishing false claims in the first place. Beginning in the 1970s and extending through recent decades, U.S. federal agencies have considered possibilities for corrective advertising as a remedy for false claims in product advertising (Aikin et al., 2015; Armstrong et al., 1983; Wilkie et al., 1984). First, corrective advertising in the United States has been a policy lever that highlights the extent to which advertising regulation has primarily been a matter of post-hoc detection of misinformation rather than prevention of (or censorship against) the initial appearance of misinformation. Second, corrective advertising, at least as demonstrated by the FDA, has primarily focused on providing accurate factual knowledge to consumers as a specific goal for mitigating misinformation (e.g., U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2022), a goal which does not necessarily address irreversible behavioral effects that may have stemmed from earlier exposure to misinformation. Additionally, such interventions can potentially return audiences to a state of knowledge that existed before misinformation exposure, but that goal is not the same as the elimination of behavioral consequences that may have occurred in the immediate wake of exposure to misinformation (e.g., product purchase or intake which cannot be undone), suggesting an important limit to this policy intervention.

Finally, during the first decades of the 21st century, researchers and practitioners began to explore and document approaches outside of regulatory policy to counteract individual misbeliefs resulting from exposure to misinformation as well as to consider further steps that might eliminate

some types of false claims from popular circulation. In the next sections, we discuss the state of the science on such approaches, which now reflects insights from many academic disciplines (e.g., psychology, education, communication, computer science) and multiple sectors (including academia, for-profit corporations, non-profit organizations, policymaking). Indeed, efforts to mitigate potential negative effects from misinformation are now more prevalent, although interventions to specifically address misinformation about science are less prevalent than for other topical domains (e.g., political misinformation). Moreover, the committee found that current efforts are largely uncoordinated across actors, domains, scientific theories, and intended outcomes.

RECENT INTERVENTIONS TO ADDRESS MISINFORMATION ABOUT SCIENCE

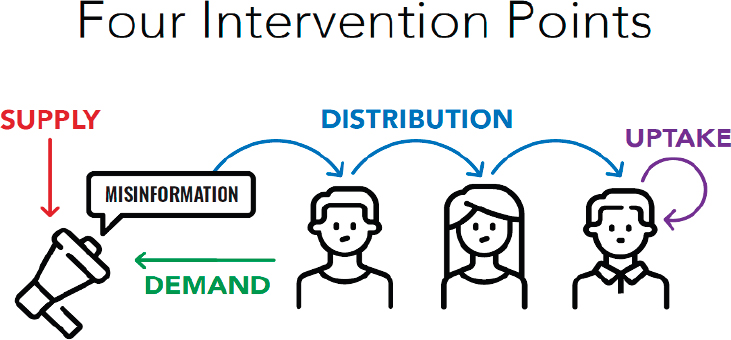

After reviewing the existing landscape of recently documented interventions intended to reduce the negative effects of misinformation about science, the committee has discerned a wide range of intervention objectives, suggesting that there are many different points at which organizations have attempted to act. Some efforts involve systems-level intervention to affect the physical prevalence of misinformation in information environments, whereas many efforts—the bulk of those reported in peer-reviewed social science literature—have addressed individual beliefs and decisions (see Kozyreva et al., 2024 for an expert review of individual-level interventions). Interventions can be designed to target different parts of the broader information ecosystem and to utilize different approaches to achieve varied goals. To organize our discussion of existing interventions, the committee has identified four places to intervene to disrupt the effects of misinformation about science: supply, demand, distribution, and uptake (see Figure 7-1).

It is important to note that these four categories are non-exclusive. For example, an intervention may aim to reduce both belief in and sharing of misinformation, thus targeting both uptake and distribution. In fact, many of the most effective misinformation interventions target multiple intervention points. Below we summarize the evidence behind some of the most popular interventions in each category. Given that many interventions target multiple intervention points we describe each intervention in the section where it best fits, but also acknowledge the interventions’ other goals.

Supply-Based Interventions

Supply-based interventions are designed to reduce the amount of misinformation circulating in society and/or change the balance between

SOURCE: Committee generated.

low-quality and high-quality information. Consequently, these interventions include approaches that might increase the prevalence of high-quality content (e.g., attempts to improve science journalism by funding non-profit newsrooms or training journalists) or reduce the prevalence of low-quality content (e.g., by penalizing low-quality content producers using tools such as boycotts, litigation, or legislation and regulation).

There is some evidence to suggest the efficacy of supply-based interventions, for example, Dunna et al. (2022); however, since these interventions typically require buy-in from social media platforms they tend to be difficult to implement, may be resource intensive, and are difficult to replicate in a scientific setting. For some of the supply-based interventions that have been proposed, such as engaging in litigation against content producers, the information that is available on them is also difficult to evaluate, and whether there is sufficient appetite for implementation remains in question (Tay et al., 2023). Although some of these interventions may be amenable to formal policy analysis and evaluation procedures, to date, this committee is unaware of formal attempts to conduct these analyses.

Some supply-based interventions that have been implemented include the imposition of a “strikes” or penalty-based system, whereby purveyors of misinformation are warned by social media platforms that they could face penalties (e.g., account suspension) for continuing to post misinformation.1 To the committee’s knowledge, the efficacy of such interventions

___________________

1 Meta: https://transparency.meta.com/enforcement/taking-action/penalties-for-sharing-factchecked-content/

has not been systematically evaluated. Other supply-based approaches, especially those that increase the prevalence of high-quality information have also, to our knowledge, not been systematically evaluated for their impact on addressing misinformation.

Demonetization

The premise of demonetization strategies is that misinformation transmission can be a profitable endeavor (also see discussion on monetization in Chapter 5). In particular, economic incentives afforded by the “attention economy” enable individuals or organizations to make money by disseminating misinformation (Davenport & Beck, 2001; Global Disinformation Index, 2019; Ryan et al., 2020). Misinformation has also spread through targeted advertisements (Jamison et al., 2019a) and has been used for marketing purposes (Ballard et al., 2022; Mejova & Kalimeri, 2020). Purveyors of misinformation may profit from their activities through several mechanisms, including earning revenue from platforms by garnering engagement (Hughes & Waismel-Manor, 2021) or by soliciting direct donations (Ballard et al., 2022; Mejova & Kalimeri, 2020). This raises the possibility that news organizations and social media platforms might be able to reduce the dissemination of misinformation by taking actions designed to reduce its economic value (Bozarth & Budak, 2021; Han et al., 2022; Papadogiannakis et al., 2023; Zeng et al., 2020).

Consistent with these findings, some social media platforms have attempted to place restrictions on advertising revenue. For example, Facebook no longer allows advertisements that promote vaccine misinformation, whereas YouTube has “demonetized” channels that promote some types of misinformation—that is, disallowing them from obtaining revenue from ads (Gruzd et al., 2023; Li et al., 2022b). Despite these efforts, there are relatively few systematic evaluations of the efficacy of such demonetization strategies (although see Dunna et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2020b), in part due to lack of access to data for researchers. Another challenge to measuring the efficacy of these is how to operationalize monetization itself with only a small number of studies (Broniatowski et al., 2023a; Herasimenka et al., 2023) providing measures of this construct. Of these, some measures have not yet demonstrated generalizability or scalability.

Deplatforming

Deplatforming refers to the removal of objectionable accounts from social media platforms (e.g., for violating those platforms’ terms of service). As a strategy for reducing exposure to misinformation, deplatforming is controversial, in part because it has often been equated with censorship and raises concerns regarding potential infringements on freedom

of speech (although one study suggests that most individuals prefer the removal of harmful online content; see Kozyreva et al., 2024). On one hand, some studies found that deplatforming purveyors of hate speech can reduce the amount of future hate speech on the platform, especially when combined with efforts to degrade the networks that they have formed (Chandrasekharan, 2017; Jhaver et al., 2021; Klinenberg, 2024; Saleem & Ruths, 2018; Thomas & Wahedi, 2023). On the other hand, some studies suggest that deplatforming objectionable accounts on one platform may simply shift their content to other, often more fringe, platforms (e.g., Ali et al., 2021; Bryanov et al., 2022; Buntain et al., 2023b; Mitts et al., 2022; Newell et al., 2021; Ribeiro et al., 2024; Velásquez et al., 2021). Notably, these fringe platforms tend to have smaller audiences, likely leading to a net reduction in hate speech online. However, reducing the volume of objectionable accounts through deplatforming may not necessarily translate to reducing exposure to misinformation (Broniatowski et al., 2023b).

Moderation

Rather than removing objectionable accounts, some social media platforms have engaged in content moderation—for example, removing or banning objectionable content or communities where that content is shared. Current content moderation methods allow for the removal of specific pieces of misinformation that meet pre-defined criteria. Such moderation has long been a part of the social media landscape, especially in the case of content that is subject to legal liability (see later discussion on governance approaches). By some measures, content removals may be deemed successful. For example, compared to prior trends, Facebook successfully removed roughly half of all posts in anti-vaccine pages and groups during the COVID-19 pandemic (Broniatowski et al., 2023b). However, no change in overall engagement with vaccine misinformation was observed, suggesting that, as with removing objectionable accounts, removing content alone may not reduce exposure to misinformation.

Typically, content moderation decisions are made by a combination of algorithms that identify potentially objectionable content (see Chapter 5 for more on the role algorithms play in shaping and moderating content), and by human content moderators with a large variance in training, linguistic competence, cultural competence, and compensation, with the latter covering the range from volunteer work, through online crowdsourced workers, to professional roles (Cook et al., 2021). However, content moderation efforts are not able to be done at the scale and speed of the mass spread of (mis)information. Additionally, only the most common misinformation is most likely to be removed, while less common or novel misinformation may still go viral before it is detected. Furthermore, algorithmic approaches to

content moderation are often brittle, easily circumvented, and subject to false positives (Gillett, 2023; Hassan et al., 2021), even when augmented with human supervision. This means that motivated purveyors of misinformation may still be able to spread it, although casual platform users may not be as likely to come across it in passing.

In addition, content moderation is challenging due to prominent definitional issues. For example, defining “misinformation” or “hate speech” in a manner that can be uniformly enforced by content moderators is difficult, and can lead moderators to focus on obsolete misinformation while ignoring new misinformation that has not yet been fact-checked (Broniatowski et al., 2023b). Even when definitions are clear, such as illegal content, determining when a specific item matches the legal definition may be difficult and is rarely scalable (Castets-Renard, 2020). See Box 7-1 for a short discussion of how the European Union (EU) is attempting to improve content moderation practices to address misinformation about science.

Finally, in general, assessing the efficacy of content moderation is challenging due, in part, to the difficulty in establishing consistent standards for defining objectionable content, and applying these standards. Thus, it is difficult to say to what extent content moderation efforts are successful, and more evidence is still needed to make that determination. Importantly, content moderation also carries with it the risk of trauma to moderators themselves (Steiger et al., 2021).

Decredentialing

The COVID-19 pandemic motivated a number of professional societies to take actions to address misinformation about science and medicine. Professional coalitions, including a broader coalition of medical specialties, set and enforce professional and ethical standards among their ranks (Jurecic, 2023). A joint effort by the American Board of Internal Medicine, the American Board of Family Medicine, and the American Board of Pediatrics supported the Federation of State Medical Boards’ position of taking disciplinary action against physicians who spread medical misinformation (Baron, 2022; Baron & Ejnes, 2022; Federation of State Medical Boards, 2021). Others, such as the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology, have also released statements informing physicians that spreading misinformation/disinformation about reproductive health, contraception, abortion, or COVID-19 could lead to loss of certification (American Board of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2021, 2022). In addition, nursing organizations such as the National Council of State Boards of Nursing have released statements addressing COVID-19 misinformation being spread by nurses and threatening discipline for nurses who disseminate misleading or incorrect information on COVID-19 and vaccines (National

Council of State Boards of Nursing, 2021). Decredentialing initiatives have been controversial, and there is currently no data on either the number of people who have lost their certifications or the impact of such revocations on the person affected, on those who follow them, or on the supply, distribution, or uptake of misinformation.

Additionally, some laws have been created to penalize individuals thought to be spreading misinformation about science not in furtherance of fraud or another crime (Buckley & Calo, 2023). For example, the California Assembly Bill 20982 defined the promotion of COVID-19 misinformation as “unprofessional conduct” for purposes of licensure standards and authorized the California Medical Board to revoke the licenses of doctors who diverged from “contemporary scientific consensus.” This bill was subsequently approved by the governor and made into law in 2022.

Foregrounding Credible Information in Algorithms

A variant of content moderation or content classification is adjusting the algorithms that shape search engine and social media content feeds to favor content produced by sources deemed to be scientifically credible. The Council of Medical Specialty Societies, the World Health Organization, and the National Academy of Medicine, for example, have recommended the coding of platform accounts to specifically label some scientific organizations to be considered for elevation in search results (see Burstin et al., 2023; Kington et al., 2021). Such work poses challenges in instances in which formal organizational accreditation is not readily available (e.g., for-profit organizations as opposed to non-profit and government entities with established vetting or accrediting procedures). Nonetheless, the establishment of clear and transparent labeling systems to identify media platform accounts as generally credible sources that rely on peer-reviewed scientific evidence could be assessed, and at least one organization—YouTube (and its parent company, Google)—has implemented some account credibility labeling. To date, there is limited empirical evidence on the effects for users of search engines or social media platforms that have adopted extensive labeling systems, and additional research that evaluates this approach is needed.

Demand-Based Interventions

Demand-based interventions are designed to reduce the consumption of misinformation. Additionally, people are not simply passive consumers of information; they often seek it out either to confirm their pre-existing

___________________

2 AB-2098 Physicians and surgeons: unprofessional conduct (2021–2022): https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=202120220AB2098

beliefs or to answer pressing questions. Thus, demand-based interventions aim to prevent people from turning to misinformation and instead provide accurate information either by filling information voids (e.g., by providing credible information to answer people’s questions), increasing trust in sources of accurate information, or by increasing people’s ability to notice and avoid misinformation (e.g., by enhancing people’s ability to spot accurate information through literacy programs).

Addressing Information Needs

People often seek out science- and health-related information in order to answer questions they may have. Many U.S. adults value scientific research’s ability to address those questions, and their confidence in scientists to act in the best interests of society has remained steady for decades (see Chapter 3). As recently as 2018, the majority of Americans reported having sought information about science in the past 30 days (National Science Board, 2022). For example, a person might ask when is it okay to leave COVID-19 isolation or even what is so special about the new space telescope? Interventions that are aimed at addressing information needs seek to ensure that people can easily find accurate, up-to-date information answering their questions (reducing the likelihood that they will be exposed to and engage with misinformation). From this perspective, what might otherwise appear to be demand for misinformation is actually the result of credible information voids.

One potential opportunity for addressing these information needs lies in interactions between health professionals and patients. Public health and healthcare organization staff can respond to patient questions and offer assistance to patients in navigating their information environments (Southwell et al., 2019). Organizations can also create specific job roles similar to what the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention did with its CARE ambassador program for travelers during the Ebola outbreak of 2014–2016 to address patient concerns about specific topics (Prue et al., 2019). However, strategies that rely on expanded capacity for audience engagement or new job roles require organizational capacity dedicated to misinformation mitigation and evaluation of that approach. For example, during the initial years of the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. National Institutes of Health Community Engagement Alliance (CEAL) in Florida partnered with the Osceola County Department of Health and local food drive organizations to answer people’s questions, share health resources, and provide information about vaccination sites (Otero, 2021). In addition, CEAL also partnered with community barber shops to provide accurate information about COVID-19 to barbers who could then listen to their patrons’ questions and concerns and provide accurate health information

(National Institutes of Health Community Engagement Alliance, 2023). This type of community interaction is likely critical for preventing or correcting misbeliefs; however, because of resource constraints, such initiatives are often thinly documented and rarely formally evaluated for their effectiveness. Nevertheless, multiple community and civil society organizations have emerged to track and combat misinformation in specific ethnic communities such as the Asian American Disinformation Table, Disinfo Defense League, Xīn Shēng Project, Co-Designing for Trust, Conecta Arizona,3 and Digital Democracy Institute of the Americas (Nguyễn & Kuo, 2023). Box 7-2 highlights a community-based organization (CBO), the Tayo Project, and how it worked to combat misinformation about science within its community. Moreover, these efforts underscore the importance of being deliberative about audience values as part of any communications effort to address their science information needs (Dietz, 2013).

Local newspapers and television stations could also help to address laypeople’s information needs, and as a result, reduce demand for misinformation (Green et al., 2023a). In general, Americans report relatively low confidence in news media compared to past decades (Pew Research Center, 2019b), but local news is one information source that is still trusted by many Americans with relatively few partisan differences. In 2022, 71% of American adults reported having some or a lot of trust in their local news organizations (Liedke & Gottfried, 2022). Additionally, local television news has broad reach: in 2022, on average, 3.1 million televisions tuned into local evening news, 3 million televisions tuned into local late news, and 2 million televisions tuned into morning news each day (Pew Research Center, 2023b). These numbers are similar to or higher than those for the most watched national news shows: in 2022, The Five, the most-watched Fox News show, averaged 3.4 million viewers, and MSNBC’s 9pm show slot, reflecting the most-watched non-Fox News shows, averaged 1.8 million viewers (Katz, 2023). It is known that trusted messengers play an important role in counteracting misinformation about science (e.g., Knudsen et al., 2023; see also later discussion on increasing trust in sources of credible science information). Thus, local news organizations may be an untapped resource for mitigating misinformation about scientific research. At least one recent study has noted that local television news stories featuring parenting and child development science can have a positive effect on parents’ perceptions of the value of such research (Torres et al., 2023). However, as discussed in Chapter 3 of this report, long-standing decreases in financial resources and the number of reliable local news sources may limit this potential (Abernathy, 2018; Hayes & Lawless, 2021).

___________________

Finally, one way to identify science information voids and circulating misinformation about science is through “social listening tools.” These tools include those developed to assist journalists and researchers with gaining transparency into social media platforms (e.g., CrowdTangle—which Meta shut down in August 2024, Pushshift, etc.), along with tools focused on specific topics (e.g., Project VCTR,4 which tracks vaccine-related media conversations) or regions (e.g., iHeard St. Louis,5 which identifies health-related

___________________

misinformation spreading in the city). Some tools focus on what people are posting or searching for online (e.g., CrowdTangle) while others directly ask community members about what they are hearing (e.g., iHeard St. Louis). These tools are designed to raise public awareness about misinformation, enabling those working to oppose misinformation (e.g., public health officials) to quickly track and adapt to misinformation narratives as they emerge (also see Chapter 8, Box 8-1). Unfortunately, these tools are not available to all researchers, and data access is often at the discretion of social media companies (Ledford, 2023; Pequeño IV, 2013; Tromble, 2021).

Increasing Trust in Sources of Credible Science Information

Reported trust in representatives of scientific institutions predicts intended adherence to information shared by that institution (see Prue et al., 2019). Trust in science as a process or trust in scientists may also discourage acceptance of misinformation attributable to other sources, and at least one intervention study has attempted to increase trust in science directly as a way of attempting to reduce acceptance of misinformation about science. Agley et al. (2021) conducted a randomized controlled trial in which participants either learned about the scientific process or did not. Perceived trust in science was slightly improved in participants who learned about the scientific process and those with greater trust in science were also less likely to believe misinformation about COVID-19. Regarding the latter finding, the authors noted that this was an indirect effect (Agley et al., 2021).

To date, research on trust in information sources has been inconsistent with respect to conceptualizing and measuring trust. In some cases, trust has been described in terms of beliefs that other people or institutions are credible or reliable (see Siegrist et al., 2005), but the concept of trust in science has not been consistently operationalized (Funk, 2017; Siegrist et al., 2005; Taddeo, 2009). In one study, residents in rural North Carolina were asked to define trust in the context of information sources about wildfires. In response, most noted the importance of perceived credibility and reliability, but at least some also noted the importance of sharing interests with the source and the specific importance of local information outlets that are economically or socially aligned with them (Southwell et al., 2021). Further, Lupia et al. (2024) noted that “confidence in science,” “confidence in the scientific community,” and “trust” are all commonly used in survey research as measures for public views of or trust in a particular information source. The term “confidence” was said to most accurately reflect the survey questions asked, and while over time, public confidence has declined in many institutions, confidence in science is higher than confidence in nearly all other civic, cultural, and governmental institutions for which data are collected (Lupia et al., 2024; also see Chapter 3). Importantly, although

respondents expressed relatively high confidence in science, they also raised concerns about the degree to which the values of scientists align with their own and scientists’ ability to overcome biases and distortive incentives in their work (Lupia et al., 2024). This is consistent with at least one case study that suggests that the values expressed by a scientist may influence audience trust in presented information (Elliott, 2017). Therefore, greater transparency in science around values and adherence to scientific norms and incentives could be an important way to improve public perceptions of science, and, as a result, increase public trust in science as a source for reliable information.

Professionals working at state and local agencies, such as departments and associations of public works and health, are trusted experts in specific areas such as emergency preparedness, disaster response, and environmental threat mitigation (Bergner & Vasconez, 2012). As such, these agencies and associations are also well positioned to engage in science communication efforts that could supplant the influence of misinformation about science. As previously noted, perceptions of economic or social similarity with an information source (in addition to intellectual credibility or reliability) influences the extent to which people perceive a source to be trustworthy. To date, the potential effectiveness of communications strategies that emphasize shared interests between audiences and institutions on enhancing trust perceptions and subsequent resistance to misinformation about science has not been adequately studied in peer-reviewed research and warrants further exploration. But in light of existing divides in trust, including more recent ideological and partisan divides that were amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic (Green et al., 2023a), such professionals may play an especially important role in communications and messaging efforts that seek to resonate with the entire population.

Opportunities for effective mitigation through trusted channels of communication may also lie directly within communities, whereby information, including about health and science, is often disseminated through intermediary institutions, such as faith-based organizations, grassroots CBOs, or community health centers (Seale et al., 2022). A recent study also showed that since the COVID-19 pandemic, organizations like museums, zoos, and science centers have also become prominent sources for trustworthy information (Dilenschneider, 2023). Serving as cultural and linguistic brokers, these institutions work to reduce barriers and promote access to a myriad of resources and information in traditionally underserved and under-resourced communities (Seale et al., 2022). More importantly, given the trust that community residents typically have in them, such intermediaries may serve as critical partners to address misinformation about science (Korin et al., 2022), particularly around filling information voids with accurate information. Indeed, various communities have established

a number of initiatives, including peer-peer education, fact-checking, and community-led media literacy programs, to resist, counter, and develop resilience against the negative impacts of misinformation about science (Nguyễn & Kuo, 2023).

Literacy Related to Science, Health, and Digital Media

People can vary in their ability to discern the accuracy and value of information they encounter based on available cues, and skills that scholars often have labeled in terms of literacy appear to play important roles in that discernment. Definitions of various types of literacy have evolved over time, although key threads have been adopted by many researchers. In the 2016 National Academies’ report Science Literacy: Concepts, Contexts, and Consequences, science literacy is defined as a multifaceted construct that requires different types of knowledge and skills for different contexts and domains (National Academies, 2016b). Furthermore, science literacy is not only influenced by cognitive factors, but also by motivational, emotional, social, and cultural factors that shape how people encounter and process science information (National Academies, 2016b). More recently, the National Science Board (2024) describes science literacy as the extent to which people understand the nature of science as an iterative process of empirical observation and testing. Additionally, it reports that such skills are linked to confidence in science. In a widely cited piece, Berkman et al. (2010, p. 16) describe health literacy as “the degree to which individuals can obtain, process, understand, and communicate about health-related information needed to make informed health decisions.” Similarly, in a recent study, Nutbeam & Lloyd (2021) indicated that health literacy is assumed to “enable individuals to obtain, understand, appraise, and use information to make decisions and take actions that will have an impact on health status” (p. 161). In the case of digital media literacy, researchers have cited the focus of Kemp et al. (2021, p. 104) on “capabilities and resources” needed to benefit from information, as a useful working definition. Literacy skills, in part, help people discern the likely accuracy of information by affording consideration of how information is generated and presented by sources.

When encountering misinformation in online contexts, people who are not familiar with the digital information environment may be less able to distinguish between signals of credible and non-credible content. Interventions to build digital media literacy skills include providing individuals with digital media literacy tips (Guess et al., 2020) that may help them to distinguish between credible and non-credible sources. An important caveat to raise regarding digital media tips involves the limited utility of some heuristic strategies. A simple recommendation to avoid websites that end

in .com or to trust .org or .gov sites, for example, ignores variation within each of these domain levels on web sources. A dot-com source of a car manufacturer or trade group can provide credible information on how electric versus gasoline-powered engines work and some .org sites are created by for-profit interest groups. Websites within each category can also have differential utility for different purposes (Polman et al., 2014; Radinsky & Tabak, 2022). Another heuristic with limitations involves a recommendation to consider the professional appearance or layout of a website; however, sophisticated purveyors of misinformation can incorporate good user design (Wineburg et al., 2022). As the digital information environment continues to change due to technological advancements, so will the useful signals of credible information. For example, the emergence of tools based on large language models (LLMs; e.g., chatbots and AI-mediated search engine results) has altered the ways that people find information and has also removed some of the credibility signals that people commonly rely on, such as proper citations and signs of uncertainty (Augenstein et al., 2024). These changes may pose additional challenges for individual navigation of the contemporary information ecosystem, and it remains to be determined what new digital media literacy skills may be needed.

A related technique, lateral reading, encourages individuals to seek out more information about a source as they are reading information from that source (Wineburg et al., 2022). The lateral reading strategy was originally developed as part of the Civic Online Reasoning initiative at Stanford University (McGrew, 2020; McGrew et al., 2018; Wineburg & McGrew, 2019; Wineburg et al., 2022) for social studies instruction. Lateral reading of websites is based on the practices of expert fact checkers, who rather than spending large amounts of time reading “vertically” within a website (i.e., from the top to the bottom of any one page), read “laterally” across multiple websites to compare and contrast information from multiple sources, as when jumping across a large set of tabs in a web browser. Fact checkers also seek to analyze evidence, and exercise “click restraint” while looking at the overview information on a search engine results page. Rather than clicking on one of the first three results as novices do, they scan through several pages of results, and open tabs to read laterally across a selected set. Although the empirical research on lateral reading strategies specifically applied to science education contexts is limited in scope (e.g., Breakstone et al., 2021; Pimentel, 2024), this approach has promise for supporting individuals (students and adults alike) in discerning the accuracy of science information, given its demonstrated efficacy in other subject areas (Breakstone et al., 2021; McGrew, 2024; Osborne & Pimentel, 2022; Wineburg et al., 2022).

A key for science educators incorporating digital media literacy into their instruction is focusing on how an understanding of science practices, concepts, and scientific expertise can inform the evaluation of science

information (Osborne & Pimentel, 2022; Polman, 2023). Knowledge of the scientific process, methods, and social norms, and aspects of the nature of science are helpful, including how replication across vetted, empirical studies builds scientific consensus and how this consensus can evolve as sometimes contradictory evidence accumulates—but this is not a reason to dismiss science evidence (see Chapter 2). Without such explicit instruction, students may know very little about the science information environment (Polman et al., 2014), and so science educators can also help them understand, for instance, that in the science enterprise, documents like press releases should not be given equal weight as consensus reports or peer-reviewed original research articles (Osborne & Pimentel, 2022; Polman, 2023). Such an approach can even be effective for adults, as demonstrated in one study conducted by Smith et al. (2022) that involved a 2.5-day boot camp training for journalists during the lead-up to the 2020 elections. As part of the training, participants learned about how science works and how to include scientific evidence in their reporting, and six months after the training, the stories written by these journalists contained more peer-reviewed scientific material and less tentative language about scientific facts compared to before the training (Smith et al., 2022).

Other media literacy interventions include technique-based inoculation, which is intended to educate individuals on how to detect signals of misinformation (Lewandowsky & van der Linden, 2021; Traberg et al., 2022). These inoculation interventions warn people about persuasive attempts and then expose people to a weakened form of the manipulation strategy to increase their resilience. For example, an inoculation intervention may teach people about the “fake experts” strategy used in many disinformation campaigns in order to increase people’s ability to recognize the technique, and as a result, their resilience against misinformation. Technique-based inoculation interventions targeting a variety of manipulative techniques (e.g., emotional language, ad hominem attacks, conspiratorial thinking) have been successfully implemented as online games (e.g., Basol et al., 2020; Maertens et al., 2021), videos (e.g., Roozenbeek et al., 2022), and articles (e.g., Cook et al., 2017), and are effective at increasing people’s ability to spot the manipulative techniques and decreasing their belief in false information. Like other educational interventions, the positive effects of technique-based inoculation wear off as people forget the intervention (typically after a few weeks); however, the benefits are longer-lasting if people are given a booster test every few weeks (Lu et al., 2023; Maertens et al., 2021). One criticism of technique-based inoculation is that it may make people skeptical of all new information rather than specifically incorrect information, in part because some of the manipulative techniques (e.g., emotional language) are also present in accurate news stories. Thus, technique-based inoculation can sometimes lead people to

be more distrustful of both accurate and inaccurate information rather than improving their ability to distinguish between the two (Altay, 2022; Hameleers, 2023; Modirrousta-Galian & Higham, 2023). Despite these limitations, initial evidence suggests that providing feedback on the ways people can be manipulated by misinformation can lead to better accuracy in distinguishing between true and false headlines (Leder et al., 2023).

Importantly, although literacy skills may affect misinformation interpretation, literacy skills alone do not appear to fully account for the sharing and spread of misinformation in a network. That means that interventions to improve literacy alone may improve understanding among some people but may not necessarily eliminate the spread of misinformation, per se. Literacy may decrease users’ demand for and uptake of misinformation while not affecting the distribution of misinformation about science. Using experimental evidence, Sirlin et al. (2021) have demonstrated that although study participants’ digital literacy was related to their ability to discern falsehood, digital literacy was not predictive of an individuals’ intention to share misinformation. As Southwell et al. (2023, p. 122) have noted, “confusion about the credibility of information or misinformation is not necessarily the same as the likelihood of sharing misinformation with peers,” but there are times when individuals may share information because they are confused.

Beyond digital media literacy, an array of efforts to teach people about how scientific institutions operate can also be considered. Although much of formal science education in the United States focuses on preparing individuals to pursue careers in science, there is evidence that learning about what scholars have labeled socio-scientific issues supports the development of science literacy, particularly for learners who do not pursue careers directly involved with science (Aikenhead, 2006; Feinstein, 2011; Feinstein et al., 2013; Polman et al., 2014; Roberts, 2007, 2011). Feinstein (2011, p. 168) has referred to this as “science literacy [for] competent outsiders.” Being a competent outsider to science involves knowing how to apply and use scientific thinking, concepts, and practices in everyday situations, one of which is discerning misinformation about science. Such a science literacy embeds epistemic understanding of how science is practiced, disciplinary core ideas, and cross-cutting concepts (NRC, 2012a, 2013). It also incorporates strategic and mindful reliance on credible sources, and application into civic and political life (National Academies, 2016b). Educating “competent outsiders” is more likely to be successful if it involves purposeful, collective sensemaking instead of solely asking people to make “individual truth judgments” (Feinstein & Waddington, 2020). This suggests possibilities for interventions that involve engaging people and local communities in learning about how scientific research is conducted and can be interpreted in the context of specific issues affecting those local communities, such as water quality monitoring. Such an approach is consistent with calls for

science communication professionals to better attend to values alongside scientific facts when seeking to inform public participation in science decision making (Dietz, 2013). However, the impact of such science education interventions on uptake of misinformation about science has not been studied.

Literacy-focused approaches have been criticized for framing the misinformation problem as one of individual vigilance and avoidance (boyd, 2017), and yet, outside of formal education contexts, such education is rarely required (Livingstone, 2011). Additionally, those who voluntarily engage in media literacy education may be motivated by pre-existing concerns with misinformation’s harmful effects, while those most likely to believe and share misinformation (e.g., older adults) may lack access to or interest in media literacy education (Moore & Hancock, 2022; Vaportizis et al., 2017). Consequently, such approaches may widen the social gaps between those who possess the knowledge and motivation to resist misinformation and those who lack it (Livingstone, 2011). These observations also suggest that while effective in some instances, media literacy alone will likely not be sufficient to counteract the problem of misinformation.

Distribution-Based Interventions

Distribution-based interventions are designed to limit the spread of misinformation. These interventions include actions taken by online platforms, such as content moderation; approaches to encourage online platforms to take action, such as through legislative means (e.g., amending Section 230 of the Communications Act of 1934, which was enacted through the Communications Decency Act of 1996); and actions aimed at reducing misinformation sharing by individuals.

Whereas supply- and demand-based interventions seek to reduce the prevalence and intake of misinformation, respectively, some distribution-based interventions seek to reduce the exposure of individuals to misinformation by targeting the online platforms on which such information may be hosted or the actions of individual users on the platforms. Like supply-based interventions, the evidence base for the efficacy of platform-level distribution interventions is limited. Nevertheless, some quasi-experimental studies have been carried out to evaluate the efficacy of specific policies including those that ban hate speech or individual accounts intentionally spreading misinformation on social media platforms (Broniatowski et al., 2023b; Chandrasekharan et al., 2017; Gu et al., 2022; Jhaver et al., 2021).

Architectural Remedies

A small number of distribution-based interventions targeting platforms’ architectures—that is, their structural design features such as groups, pages, and interaction options—have been proposed. For example, Broniatowski et al. (2023b) observed that vaccine misinformation on Facebook during the COVID-19 pandemic was facilitated by complex interactions between Facebook’s page, group, and newsfeed structure. Furthermore, while not currently the case, Forestal (2021) proposed a framework for how social media platforms could be explicitly designed to promote deliberative democracy and build communities that are not as receptive to misinformation. Key design elements proposed included the establishment of a community with a durable presence, clear community boundaries, and flexible incorporation of new members, thereby enabling users to engage in fundamental civic practices (Forestal, 2021). Preliminary evidence also suggests that some interventions involving the use of community structures may effectively lessen the likelihood of misinformation being created and spread (Abroms et al., 2023). Though not specific to science, there is moderate evidence demonstrating that the fact-checking skills of groups of lay users on social media are comparable to professional fact-checkers, and therefore can be effectively harnessed to reduce the spread of misinformation in news content on social media platforms (Allen et al., 2021, 2022; Banas et al., 2022; Godel et al., 2021; Martel et al., 2024; Pennycook & Rand, 2019). Specifically, lay users assign ratings to news content based on accuracy, quality, or trustworthiness. These crowdsourced ratings can then be incorporated into social media ranking algorithms, leading to a reduction in the visibility of inaccurate, low-quality, or untrustworthy content.

“Soft” Content Classification Remedies

Several approaches to reducing the distribution of misinformation implement “soft” content remedies (Goldman, 2021; Grimmelmann, 2015). Most of these remedies are premised on the idea that content distribution is driven by algorithmic amplification. For example, this content might be highly ranked within a given social media platform’s content recommender system. Consequently, information that has been classified as misinformation may be demoted or completely removed from algorithmic recommendations, meaning that the content is still present, but that it would rarely, if ever, appear at the top of a social media user’s feed since other content would displace it. This approach is limited by the fact that a platform representative is needed to classify particular content as misinformation, which may not be noticed until it has already gone viral. Therefore, a related approach seeks to downrank such content using correlates of viral

misinformation (e.g., angry reaction emoji; Broniatowski et al., 2023b). A third approach seeks to identify content that is likely to go viral before it has done so, by introducing friction into the content recommendation system, and thus enabling content moderators a chance to review and, if necessary, downrank content before it has caused harm (Kozyreva et al., 2024). One such approach, known as a viral circuit breaker, briefly pauses, and then flags, classes of certain viral content for review before it is allowed to widely spread (Simpson & Conner, 2020). To date, the efficacy of these approaches has not been tested by researchers outside of social media companies.

Content Labeling

Rather than removing or demoting individual posts or users, platforms can also choose to label content with additional information (see Morrow et al., 2022, for a review) in order to reduce the spread of misinformation. For example, a post may be labeled as “False information reviewed by independent fact-checkers,” or posts may include a banner label, e.g., “Visit the COVID-19 Information Center for vaccine resources,” along with a link. Both of these content-labeling approaches have been or are currently used by social media companies (Polny & Wihbey, 2021). However, aside from source labels and warning labels (see later discussion on these uptake-based interventions), very little research has examined the effects of other types of labeling, such as indicating that content has been manipulated or created by artificial intelligence; providing information about who else has shared the content; or providing additional context around when an article was first written, or a photo was first posted (to prevent, for example, a photo from a 2015 conflict being presented as if it happened yesterday). More research is needed to understand the effectiveness of the different types of content labels currently used by platforms and to create novel labels that may be even more effective. Moreover, insights from the behavioral sciences, library sciences, and food sciences could also contribute to an understanding of the effects of content labels in specifically addressing misinformation about science (Lorenz-Spreen et al., 2020; Wolkoff, 1996; Yeh et al., 2019).

Mathematical Simulation Models

In the absence of comprehensive data, another distribution-based approach involves the use of mathematical simulation models to forecast the efficacy of different types of interventions (e.g., Bak-Coleman et al., 2022; Johnson et al., 2019). The units of analysis of these models differ between studies, with some investigators focusing on individuals and others focusing on clusters of users (e.g., pages on social media platforms, in which a

small number of administrators may broadcast content to a large number of potential followers). These models are used to generate simulated outcomes and suggest potential remedies such as content removal, viral circuit breakers, and deplatforming. While each method alone is predicted to have some benefit, the largest reductions in the spread of misinformation is predicted to be when multiple approaches are combined (Bak-Coleman et al., 2022).

Psychology-Based Interventions

A separate class of interventions seeks to use insights from individual human psychology to reduce misinformation receptivity and distribution. These interventions are motivated by different theoretical frameworks. For example, accuracy nudges grow out of dual-process theories (e.g., Stanovich & West, 2000), which presume that humans believe and share misinformation because they are not paying attention to signals of misinformation (Pennycook & Rand, 2022a). Consequently, accuracy nudges seek to encourage individuals to consider the accuracy of content that they encounter, typically by asking people to rate the accuracy of one or more social media headlines. Overall, accuracy nudges reliably decrease people’s intentions to share misinformation (Pennycook & Rand, 2022a) and their actual sharing behaviors (Pennycook et al., 2021). The approach is also very easy to implement and scale. However, the reported positive effect is very small and likely declines quickly (Pennycook & Rand, 2022b). In addition, the accuracy nudge approach is only effective when people have the knowledge required to determine if the information is correct or incorrect (Pennycook & Rand, 2021).

Similarly, friction-based approaches aim to slow down decision making and provide people with an opportunity to rethink their initial choices. For example, asking people to explain how they know that a headline is true or false has been shown to decrease intentions to share, in the case of false headlines (Fazio, 2020a; Pillai & Fazio, 2023). Friction-based interventions have also been employed on some social media platforms to encourage reading an article before sharing (Hern, 2020), to promote civil discussions (Lee, 2019), or to reduce sharing of unverified information (Fischer, 2021). The efficacy of such approaches used by social media platforms needs further research and some of the information that could be helpful for researchers to better understand these approaches may not be readily accessible.

Finally, fuzzy-trace theory posits that people make decisions based on meaningful gist mental representations, which are moments where a person recalls the overall general meaning of something but not the verbatim context (Reyna, 2021). According to this theory, people may be encouraged to share or resist information if they are presented with messages explaining

the essential bottom-line meaning of the decision to share this information in terms that cue motivationally-relevant values. For example, a person may be more prone to remember that there is a huge increase in the likelihood that their child could get sick if un-vaccinated than to remember an actual number that their doctor provides; this difference plays into their decision making on whether to vaccinate their child (Reyna, 2021). Thus, unlike other dual-process approaches (which aim to promote reliance on effortful deliberation) and social-psychological approaches (which aim to take advantage of social cues in lieu of deliberation), gist-based approaches seek an intermediate approach, which provides a person with a rationale for making a decision (e.g., sharing or not sharing content) that is motivationally relevant (see Reyna et al., 2021, for a review).

Governance Approaches

Legislative, regulatory, or voluntary actions taken by governments, private citizens, and/or corporations as oversight for the informational environment have also been deployed to govern the spread of misinformation about science. For example, fines, penalties, or litigation targeting purveyors of false content fall within this category, as well as regulations and laws that might make content distributors liable for the spread of misinformation.

With respect to advertising content, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) enforces truth-in-advertising laws whereby all advertisements “must be truthful, not misleading, and, when appropriate, backed by scientific evidence” (FTC, n.d.). The enforcement of these laws applies to any medium where advertisements appear including magazines, television, billboards, or online. Further, the FTC pays special attention to advertisements with claims that can directly impact consumers’ health or finances (e.g., food, over-the-counter medicines, vitamins and dietary supplements, alcohol, and tobacco). Specifically, in cases of deceptive advertising in health and fitness, the FTC works in coordination with the FDA and also the National Institutes of Health (NIH) regarding the substantiation of health-related claims. Direct actions taken by the FTC when an organization is in violation of any truth-in-advertising law include sending a warning letter to the company about the unlawful conduct and the possibility of facing a federal lawsuit if the company continues such conduct (FTC, n.d.). The FTC reports that this is one of the most effective ways that the agency eliminates false and misleading information from the marketplace, given an overwhelming majority of companies quickly take steps to come into compliance upon receiving FTC warning letters (FTC, n.d.).

Similarly, the FDA works to provide numerous avenues to address concerns around misinformation. For example, its website contains multiple

resources for the general public in different languages on how to identify misinformation online and how to file a report about misinformation to the appropriate channels (FDA, n.d.a). The FDA also routinely hosts workshops and podcasts episodes focused on misinformation about specific public health concerns including cancer, COVID-19, and mpox (FDA, n.d.b). In July 2024, the FDA announced new revisions to its draft guidance on addressing misinformation about medical devices and prescription drugs. Specifically, this guidance seeks to provide organizations with approaches to address misinformation about medical products created by an independent third party, and to ensure that the general public is receiving the “accurate, up-to-date, science-based information they need to inform their decisions about medical products to maintain and improve their health” (FDA, 2024, p.2). At the time of this consensus report, the draft guidance was still pending approval.

In recent years, the Communications Decency Act under the regulatory authority of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has received a great deal of attention in the context of governance approaches to addressing misinformation online, and namely Section 230 of the Act (National Academies, 2021), which was enacted by Congress in 1996 to foster the growth of the internet by providing certain liability immunities to internet-based technology companies (see Box 7-3 for a brief history of this legislation). Since this time, the internet has evolved in unanticipated ways, and concerns about issues like concentration of power, misinformation and disinformation, algorithmic-mediated content and advertising, and online abuse have motivated the exploration of potential solutions that include revisions to Section 230 (National Academies, 2021). Indeed, multiple proposals have been made to amend Section 230 as a way to govern misinformation; these efforts fall into three categories, as described below (Buckley & Calo, 2023).

The first category includes efforts that seek to increase platform transparency and regulate certain categories of problematic speech as a response to the concern that certain types of misinformation are being spread unchecked. Some efforts in this category also seek to address Section 230’s disproportionate impacts on women, people of color, and LGBTQIA+-identifying people. The second category includes actions by legislators that are directed toward a specific subcategory within a platform that can be subject to liability. In this way, legislators have the opportunity to limit a given platform’s immunity or to make platforms “earn” immunity by changing how they monitor and manage inappropriate content. Finally, the third category involves concerted efforts to reduce or completely remove a platform’s immunity protections provided under Section 230 by revealing biased moderation and content removal practices (e.g., only sanctioning certain groups of people). In contrast to such proposals for reform, some have argued that changes to Section 230 could result in the over-policing

of speech, the shutting down of internet services, and other unintended consequences (Buckley & Calo, 2023; National Academies, 2021). In 2023, two cases6 involving Section 230 were argued before the Supreme Court as part of an effort to determine whether algorithmic recommendation of user-generated content could subject platforms to liability for that content; however, the Court relied on other statutes without fully addressing the scope of Section 230 (Holmes, 2023).

Attempts that seek to address misinformation about science through regulation may also be limited by the First Amendment, namely the

___________________

6 See Twitter, Inc. v. Taamneh, https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/21-1496_d18f.pdf, and Gonzalez v. Google LLC, https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/211333_6j7a.pdf

commitment to free speech in the United States, which overall is desirable, but may leave allowances for some online misinformation to go unchecked. For instance, the fact that misinformation is misleading or even untrue does not necessarily remove it from the ambit of free speech protections (Buckley & Calo, 2023). Specifically, the First Amendment states:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.7

Notwithstanding the reference to “Congress,” the First Amendment has been interpreted to apply to any state actor, meaning anyone representing the federal or local government; however, individuals and institutions operating in a private capacity are not subject to the First Amendment. That is, a private company does not necessarily implicate the First Amendment when it decides to take down certain content (Buckley & Calo, 2023). Some legal scholars8 observe that courts interpreting the First Amendment must answer at least two questions. The first is “coverage,” that is, whether the content or activity at hand is protected by the Constitution at all. Assuming First Amendment coverage, the court then has to decide what level of scrutiny to apply. Prior restraints on speech, as well as government actions that discriminate based on viewpoint or content, are subject to strict scrutiny. However, the regulation of commercial speech, that is, advertising or economic solicitation, receives a higher level of review by the courts, and statutes and regulations routinely require disclosure of truthful information, such as when the FDA requires warnings on cigarettes. But while there are narrow cases wherein misinformation may be subject to regulation and liability, how free speech doctrine may or may not hinder the extent to which misinformation about science can be regulated remains a thorny issue. For now, opportunities to dampen or penalize claims of misinformation about science are still possible when they are associated with commercial activity (e.g., false claims that a vitamin is effective in treating a medical condition), involve fraud, or are specifically intended to cause certain kinds of harm such as a financial panic (Buckley & Calo, 2023).

Finally, a more promising route for governing misinformation may involve required reporting or labeling of content, given laws or regulations that mandate disclosure tend to fare better than limits on speech. For example, recent amendments to Washington State election law require political

___________________

7 U.S. Constitution, First Amendment.

8 Frederick Schauer, Speech and “Speech”—Obscenity and “Obscenity”: An Exercise in the Interpretation of Constitutional Language, 67 GEO. L.J. 899 (1979).

actors to label the use of deepfakes in election-related media (Senate Bill 5152, 2023), and California’s law requires that political or commercial automated accounts or “bots” come with warning labels (California Code, Business and Professions Code - BPC § 17940 et seq (SB 1001); also, see Buckley & Calo (2023).

Uptake-Based Interventions

Uptake-based interventions are designed to reduce the effects of misinformation on people’s beliefs or behaviors. These interventions assume that misinformation is already present online and seek to limit its effects using techniques such as fact-checking, educational and literacy campaigns, and psychological interventions. Such interventions can either come prior to exposure (e.g., prebunking), during exposure (e.g., source credibility labels), or after exposure (e.g., debunking and motivational interviewing), but all share the goal of preventing misbeliefs.

Prebunking

In contrast to debunking interventions that occur after exposure to misinformation, prebunking occurs before people are exposed to misinformation. Such interventions can include the technique-based inoculations summarized above (e.g., Traberg et al., 2022) along with warnings presented immediately before viewing online misinformation (e.g., Brashier et al., 2021; Grady et al., 2021). Quasi-experimental evidence suggests that such warnings might have reduced the number of “likes” of anti-vaccine content on some social media platforms (Gu et al., 2022). In addition, prebunking can include warnings about certain topics, narratives, or arguments that are often used in misinformation (e.g., Jolley & Douglas, 2017; Maertens et al., 2020). The latter type of prebunking is sometimes called issue-based inoculation (van der Linden et al., 2023). For example, in one study, some British parents read a short article refuting common antivaccine conspiracy theories prior to reading an article containing vaccine misinformation, while others were exposed only to the misinformation (Jolley & Douglas, 2017). Participants in the first condition were less likely to believe that vaccines are dangerous and had higher vaccination intentions in a hypothetical scenario. Misinformation about science often repeats common themes and narratives, making it an ideal topic area for such content-based prebunking interventions. However, to date, there is significantly more research on the effectiveness of warning people about manipulative techniques than warnings about common misinformation themes and narratives.

Source Labels

Source labels provide information about the credibility of a source based either on the outlet’s adherence to common journalistic standards or a reputation for spreading misinformation. In laboratory studies, the inclusion of this source information improved participants’ discrimination between true and false claims and decreased liking and sharing of false posts (Celadin et al., 2023; Prike et al., 2023). However, a large field study found that providing source labels on social media posts, visited URLs, and search engine results did not reduce people’s intake of information from low-quality sources (Aslett et al., 2022). The benefits of source labels are likely modified by how noticeable they are and whether people pay attention to the label; for example, Fazio et al. (2023) show evidence that people do not regularly attend to many credibility signals. In addition, there is some evidence that when judging the accuracy of a headline, people are more swayed by the plausibility of the headline rather than the reliability of the source (Dias et al., 2020). Finally, as discussed in Chapter 4, misinformation about science can originate even from generally trustworthy new sources or other sources of credible science information; therefore, source labels may not be sufficient as a standalone approach to help consumers avoid misinformation. While overall, source labels show some promise as a misinformation intervention, the details of implementation are important, and more field studies are necessary to examine their effects on misinformation intake, sharing, and belief.

Debunking

Any correction that comes after exposure can be considered a debunking intervention. Sometimes also described as fact-checking, debunking approaches can be implemented at multiple levels of detail, ranging from simple statements that a given statement is false to a very detailed article-length refutation. Debunking is one of the most well-studied misinformation interventions (see Lewandowsky et al., 2020 and Prike & Ecker, 2023 for a guidebook for practitioners), and correction of misbeliefs stemming from false claims about science has been implemented by a wide range of groups, including federal government agencies (e.g., Aikin et al., 2017) and university research groups (e.g., Lewandowsky et al., 2020).

Researchers have examined the corrective effect of misinformation debunks in controlled laboratory studies (e.g., Ecker et al., 2017, 2020; Swire-Thompson et al., 2021) and in field tests in real-world situations (e.g., Bhagarva et al., 2023; Bowles et al., 2023; Pasquetto et al., 2022; Porter & Wood, 2021; Porter et al., 2022). In general, debunking is more effective when an alternative factual explanation is provided (Kendeou et

al., 2013; Lewandowsky et al., 2012; Seifert, 2002). For example, to correct the misbelief that meteors are hot when they reach Earth, a more effective debunk will explain why meteors are cool (the outermost layer gets vaporized when entering the atmosphere and the inside does not have time to heat up again), as compared to just stating that the claim is false (Kendeou et al., 2019). In addition, debunks that provide more detailed information (particularly more than a simple true/false label) tend to be more effective and have a longer lasting effect (Chan & Albarracín, 2023; Ecker et al., 2020). Debunks are also more effective when they come from trusted sources, again emphasizing an important role for trust in addressing misinformation (Ecker & Antonio, 2021; Pasquetto et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2021).

Additionally, there have been reported concerns that misinformation debunks could backfire and actually increase belief in misinformation for some recipients (e.g., Nyhan & Reifler, 2010, 2015); however, large-scale replications have found no evidence of widespread backfire effects (Haglin, 2017; Nyhan et al., 2019; Wood & Porter, 2019). In their summary of the literature on backfire effects, Swire-Thompson et al. note that “it is extremely unlikely that, at the broader group level, […] fact-checks will lead to increased belief in the misinformation” (Swire-Thompson et al., 2020, p. 292). People do vary in their acceptance of corrections (e.g., Susmann & Wegener, 2023); however, their beliefs tend to remain stable after reading a correction rather than increasing.