Understanding and Addressing Misinformation About Science (2025)

Chapter: 6 Impacts of Misinformation About Science

6

Impacts of Misinformation About Science

In this chapter, we examine the impacts of misinformation about science with the aim of understanding those that most warrant intervention to prevent harm to individuals, communities, and society. Misinformation has the potential to disrupt the ability of individuals to make informed decisions for themselves, their families, or their communities; to further existing harms and negative stereotypes about groups that exacerbate discrimination and stoke violence; to distort public opinion in ways that limit productive debate; and to diminish trust in institutions, which is important to a healthy democracy. However, not all misinformation is equally consequential, and the relationship between misinformation and its impacts are neither simple nor linear.

As described in Chapter 3, the phenomenon of misinformation about science does not exist in a vacuum. Changes in the contemporary information ecosystem and a range of social, technical, historical, and societal forces affect the information individuals seek and encounter by virtue of both their individual characteristics and choices, and in how they and their communities may be differently situated with respect to the information ecosystem. As a result, the effects of misinformation about science are also differential (Samudzi, 2017; Singh et al., 2022; Southwell et al., 2023). Effects on individuals are influenced and shaped by their own individual characteristics and views (van der Linden et al., 2023), as well as by the structural and cultural contexts of their lived experiences, access to material and social resources, and community embeddedness of their social lives (Crenshaw, 2017; Goulbourne & Yanovitzky, 2021; McCall, 2005; Smedley, 2012). Moreover, in addition to differences among individuals

and communities, not all misinformation is equal in terms of reach, scale, attention, and likelihood to be believed and acted upon, as discussed in Chapters 4 and 5.

The inherent difficulty of demonstrating causal links within a complex and interrelated system of factors poses a challenge for decision making about whether and how to intervene to address misinformation about science. On the one hand, focusing only on the limited evidence that clearly implicates misinformation as the direct cause of harm could suggest less intervention than might be warranted to prevent harm (Ecker et al., 2022; Lewandowsky et al., 2017). Conversely, making decisions based primarily on concerns about exposure to misinformation without examining the factors and nuances that shape whether and when that exposure leads to harm could lead to interventions that are excessive, antidemocratic, or counterproductive (Krause et al., 2022; Nyhan, 2020).

Despite the limited evidence for simple, linear connections between misinformation and individual behavior, there are certain situations where misinformation has greater potential for harm. We argue that the potential for harm is greater when the effects happen at scale in ways that disrupt individual agency or collective decision making, as well as when information is amplified by elites or part of a well-resourced campaign; when the effects are potentially severe, as with life and death decisions and those that provoke violence; and when the misinformation has the greatest potential to exacerbate existing harms, as when communities experiencing racism or health disparities are targeted.

In this chapter, we first discuss the nature of evidence about the impacts of misinformation. Subsequent sections describe the evidence for the impacts of misinformation for individuals, communities, and society, and the implications for informing decisions about intervention.

THE NATURE OF THE EVIDENCE ABOUT THE IMPACTS OF MISINFORMATION

We consider multiple types of evidence, including randomized control trials (RCTs)/experiments, longitudinal studies, correlational studies, and case studies that elucidate (a) the mechanisms by which misinformation can potentially cause harm at the individual, group, and societal levels and (b) the evidence that exists about the harms that can be attributed to or are associated with misinformation about science. Although experiments and longitudinal studies provide stronger causal evidence than do correlational and case studies, the latter provide useful information about how misinformation affects individuals and society at large.

Accurately measuring and documenting the precise causal effects of misinformation is difficult. Human beliefs and behaviors are influenced by

many interacting factors, challenging researchers’ abilities to directly measure the effects of misinformation in isolation. Although from an experimental design perspective RCTs provide strong evidence of these types of direct effects, there are very few RCTs on the effects of misinformation for both ethical and practical reasons. Ethically, decisions to purposefully expose people to false information should be made with great care, balancing the benefits of the knowledge learned to the potential harms to participants. Practically, RCTs are not always well suited to addressing some of the most important questions about the effects of multiple and prolonged exposures to misinformation about science, which has been likened to the effect of drops of water on a rock. The impact of each individual drop is difficult (if not impossible) to measure, but over time the water can completely change the shape of the rock (Wardle, 2023). Further, RCTs are designed to measure the average effect of an intervention on a sample (e.g., the effect of exposure to misinformation on U.S. adults). However, a focus on average effects misses potentially large changes at the ends of the distribution or on specific subsamples of the population. Misinformation that has no effect on most of the population but leads to large behavioral changes in a small minority can still, in theory, have harmful effects. Other methodologies may be more apt for making causal inferences for phenomena that occur in complex systems (Sugihara et al., 2012), and where random assignment is not possible, including matching on potential confounding variables and using panel designs that combine cross-sectional and time-series data (see Lorenz-Spreen et al., 2023 for a more complete discussion).

There are other limitations that make studying consequential impacts challenging. The effects of misinformation on different populations and communities remain understudied (Collins-Dexter, 2020; Soto-Vásquez, 2023). The gray literature from organizations whose research focuses on these populations have provided an important source of information for this report. In addition, few studies measure the effects of misinformation at the group and societal levels, though this is an important area for further study (Broda & Strömbäck, 2024).

IMPACTS OF MISINFORMATION FOR INDIVIDUALS

Much of the popular interest and research on the effects of misinformation has focused on the individual (Phillips & Elledge, 2022), and how it affects their beliefs, knowledge, attitudes, and/or behaviors. The following sections describe the relationship of misinformation about science to misbeliefs, the factors that make some individuals more receptive to misinformation when they encounter it, and the relationship of misinformation about science to detrimental behaviors at the individual level.

Holding Misbeliefs

For individuals, the most direct consequence of misinformation is that it alters people’s beliefs and causes misbeliefs (i.e., false beliefs; Adams et al., 2023; van der Linden et al., 2023). In the view of this committee, holding misbeliefs about science can be harmful because it can disrupt individual agency. When people hold misbeliefs caused by misinformation, they lose the ability to use the best information from science to make informed choices and, as a result of this loss, face an increased likelihood of acting against their best interests and those of their families and communities. The potential harms from this disruption are further compounded when it occurs at scale. To more fully understand where potential harms from misinformation may be greatest, it is useful to examine the forces that increase the likelihood that an individual will be more receptive to believing misinformation when they encounter it.

Forces That Shape People’s Beliefs

People encounter information (or misinformation) with their own sets of pre-existing beliefs, personal and social commitments, values, and goals. These, along with the natural human cognitive biases and heuristics that all people have and use (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974), shape how and the extent to which people search, uptake, and ultimately use information when making decisions. Decades of work have demonstrated people’s tendencies to selectively seek, attend to, evaluate, and recall information that confirms one’s prior beliefs or values, while ignoring or dismissing information that contradicts them (Kunda, 1990). These processes, including motivated reasoning (Kunda, 1990) and confirmation bias (Nickerson, 1998), can lead to biased assimilation of evidence, where information that is perceived to be in line with what we have encountered previously is generally treated with less skepticism and is more readily accepted as true or accurate (e.g., Pennycook et al., 2018). The evidence suggests that there is a recursive relationship that involves holding misbeliefs; seeking (mis)information about those misbeliefs; encountering similar, but new, misinformation; and adopting new misbeliefs (e.g., Slater, 2007).

This tendency to seek out or believe information that confirms preexisting views can be especially robust for scientific topics that are the subject of political debate or when a topic becomes associated with a political figure or party, or for other topics about which people already have strong opinions (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [National Academies], 2017; Stroud, 2008). When these beliefs comport with important identities and worldviews, people can also develop increasingly strong and polarized attitudes and resistance to attitude

change (Lord et al., 1979; Nickerson, 1998; Taber & Lodge, 2006). These processes can also affect how people perceive the credibility and trustworthiness of scientific sources and experts, and the likelihood that people will selectively trust or distrust scientific authorities depending on their alignment with their ideological preferences or group identities (Lewandowsky & Oberauer, 2016). Moreover, encountering information repeatedly over time likely increases perceptions that such information is accurate and can be relied upon to inform decision making, and this applies to encountering misinformation about science as well (Pillai & Fazio, 2021; Unkelbach et al., 2019).

Well-established models of decision making (e.g., Theory of Planned Behavior; Value-Belief-Norm Model; e.g., Dietz, 2023; Steg, 2023) also highlight how values shape what people believe to be true and highlight too the role of norms and identity in how people make sense of information. On issues that may be associated with an important identity (e.g., environmentalist), people consider what they believe people “like them” do or should do (Dietz, 2023). Other dimensions, including concern for others (empathy) and reliance on others (trust) or perceptions of self- and collective-efficacy also impact decisions and behaviors, particularly around assessments of risk. Perhaps one of the most important contributions from these literatures is the consistent finding that people generally do want to act in accordance with the best available evidence but also in ways that are consistent with their pre-existing beliefs, values, and goals. These dual commitments can provide an opening for misinformation to warp decision making. For example, misinformation about the potential downsides of transitioning one’s home heating and cooling system from a fossil fuel-burning furnace to an electric heat pump may stop an individual from choosing to do so because of pre-existing (mis)beliefs about a related but distinct issue (e.g., whether climate change is driven primarily by human actions).

Finally, decades of research in social psychology and allied fields have repeatedly revealed how foundational social interaction is to an individual’s interpretation of the information they encounter throughout the course of their daily life. For example, network homophily is a well-known phenomenon in which people with similar beliefs tend to cluster together, meaning that they are less likely to be exposed to new information (Henry et al., 2021). In addition, foundational work on social conformity, interpersonal influence, and social norms (e.g., Asch, 1951; Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004) helps to explain how misinformation can continue to propagate through social networks, influence individuals’ and groups’ understanding of the world, and (in some cases) shape individual and collective decision making, even when that information is seemingly easy or obvious to identify as false or misleading. As a result, learning about new ideas can be inhibited (see Henry, 2017 for a review on the relationship between networks and learning in public policy contexts).

This foundational work helps to explain the cognitive biases and heuristics that all people have and use to navigate the world. They also help to demonstrate the importance of understanding how individuals may be situated in the broader context discussed in Chapter 3 and differentially exposed to the sources of misinformation about science discussed in Chapter 4. Patterns of declining trust in institutions, including shifts in increasing political and ideological divides, and experiences with structural inequities are forces that can intersect with pre-existing beliefs, values, and attitudes. They may also play a role in shaping the groups that an individual associates with in person and online, the norms and identities associated with these groups, and the sources that people believe and trust for information. Such patterns and experiences also highlight the potential for existing views and attitudes to be reinforced and strengthened through features of online information environments. However, as discussed in Chapter 3, the evidence on the extent to which people interact in echo chambers is mixed. In the next sections, we turn to discussions of the factors associated with the nature of exposure to misinformation and characteristics of an individual that can play a role in increasing receptivity to misinformation, potentially causing consequential misbeliefs about science.

Increased Receptivity to Misinformation About Science

Research shows that most people believe some misinformation (Berinsky, 2023), but it is useful to examine what factors may lead some people to be more receptive to it when they are exposed to it. Receptivity encompasses both active and passive consumption and acceptance of misinformation about science. In the view of the committee, receptivity is a more apt term than the more passive term, “susceptibility.”

Exposure to misinformation leads to misbeliefs just as exposure to accurate science can teach people correct information (van der Linden et al., 2023). This has been demonstrated in meta-analyses of experimental studies in lab settings (Chan & Albarracín, 2023; Chan et al., 2017) as well as in real-world settings (e.g., Feldman et al., 2012). Specifically, Feldman et al. (2012) found that exposure to misinformation about climate change from news media was associated with misbeliefs about global warming, despite controlling for a range of potential demographic, media use, and other predispositions. Further evidence for the effects of exposure to misinformation on beliefs also exists for topics outside of science (see Butler et al., 1995; Kim & Kim, 2019).

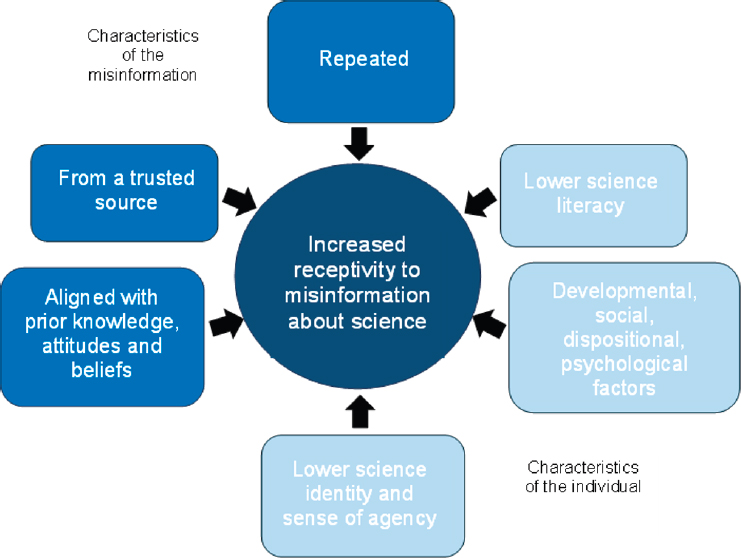

As Figure 6-1 depicts, characteristics of the misinformation and characteristics of the individual (and the confluence of these two sets of characteristics) can impact how people evaluate misinformation and to what extent they are receptive to it. In the sections that follow, we outline

SOURCE: Committee generated.

the evidence for each set of characteristics and conclude with a brief discussion of the implications.

Repetition and Trusted Sources

Exposure to misinformation is more likely to lead to misbeliefs when it is repeated and when it is from a trusted source. Characteristics of information and the persuasive tactics employed in designing and sharing (mis)information can undoubtedly influence the extent to which audiences are receptive to that information. Repetition, for example, plays a large role in people’s beliefs. Over 40 years of research finds that repeated information is more likely to be judged as true than novel information (see Dechêne et al., 2010 for a meta-analysis and Unkelbach et al., 2019 for a recent review). Repetition can increase belief in simple trivia statements (e.g., Fazio, 2020b), true and false political news headlines (Pennycook et al., 2018), advertising claims (Hawkins & Hoch, 1992), conspiracy theories (Béna et al., 2023), and health-related headlines (Pillai & Fazio, 2024). What’s more, repetition can influence belief even when people have prior knowledge that contradicts the misinformation (Fazio, 2020b; Fazio et al., 2015). For example, repetition has been shown to increase

belief in the false statement, “The Minotaur is the legendary one-eyed giant in Greek mythology,” even among people who were able to correctly indicate that a one-eyed giant is called a Cyclops (Fazio et al., 2019). These effects of repetition can occur both in lab-based settings (see Henderson et al., 2022, for a review) and when the repetitions occur in daily life (Fazio et al., 2022; Pillai et al., 2023). These findings suggest that well-resourced efforts capable of repeatedly reaching large audiences with misinformation may be particularly consequential.

Misinformation that comes from a trusted source also impacts receptiveness. When individuals encounter information about science, they appraise the credibility of the communicator (knowledge or perceived competence), their confidence in the communicator or source, and their intentions for sharing the information (Fiske et al., 2007; Lupia, 2013; Mascaro & Sperber, 2009; Shafto et al., 2012). As described in more detail in Chapter 3, the levels of trust, credibility, and confidence that people have in science, scientists, knowledge-producing institutions, and sources of information about science affect what they believe and will act upon. For example, confidence in science or scientists may play an important role in how willing people are to act on scientific information or advice based on it (Lupia et al., 2024). Actions by the scientific community that demonstrate trustworthiness and accountability, including demonstrating commitments to scientific best practice, transparency, and open access, may play important roles in the public’s confidence in science (Lupia et al., 2024). In addition, as described in Chapter 3, communities who have experienced current or historical harms from science may have lower levels of trust in authoritative sources of scientific information. These relationships may help to explain why misinformation from sources that are more likely to be believed and trusted (e.g., misinformation due to misuses of the cultural authority of science or misinformation amplified by trusted “elites”) can be especially consequential (O’Brien et al., 2021). However, some have noted that rather than being more receptive to misinformation, many people are increasingly skeptical of all new information and unsure of what to believe (Equis Institute, 2022).

Aligned with Prior Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs

As described in the earlier section of this chapter, individuals may consciously or subconsciously compare new information they encounter to their existing understanding. Individual differences in literacies (i.e., media, informational) and existing knowledge may directly predict holding misbeliefs (see Ecker et al., 2022), but this is, itself, not evidence for effects of misinformation about science. However, these individual differences may predict greater receptivity and different types of reactions to misinformation about science, including the extent to which individuals engage with

misinformation, adopt new misbeliefs or engage in problematic behaviors following exposure.

Holding strong attitudes or firmly-held prior beliefs about a topic has been associated with having lower objective knowledge about that topic, but in general there appears to be weaker effects of misinformation on attitudes than on beliefs (van der Linden et al., 2023). Fernbach et al. (2019) found that people in the United States holding extremely negative attitudes toward genetically modified (GM) food (i.e., extreme GM opponents) had both low levels of objective knowledge about the science behind GM food and high levels of self-assessed knowledge (see Chapter 5’s discussion of “do your own research” as a recurring theme associated with misinformation about science). They also found that this pattern applied to opponents of gene therapy, another application of genetic engineering technology. Similarly, Motta et al. (2018) found that anti-vaccine policy attitudes in the United States were associated with low levels of objective knowledge about vaccines and immunology, but high levels of perceived understanding. In both cases, the authors suggested that providing factual information or correcting misconceptions may not be enough to change people’s attitudes, as they may be resistant to new evidence or alternative perspectives.

Not all studies have found a negative relationship between knowledge and extreme attitudes, at least when those extreme attitudes are positive. For example, Fonseca et al. (2023) conducted a survey of U.K. adults and found that people with strong attitudes toward genetics (whether positive or negative) had higher levels of self-confidence in their understanding of science than those with more ambivalent attitudes. However, compared to those who are more ambivalent, those with strongly positive attitudes had higher levels of objective knowledge. Those with strongly negative attitudes had lower levels of objective knowledge than those who were more ambivalent. The authors proposed a model to explain this finding: the more someone believes they understand the science, the more confident they will be in their acceptance or rejection of it (Fonseca et al., 2023).

The “Dunning-Kruger” effect, described as when “people suffering the most among their peers from ignorance or incompetence fail to recognize just how much they suffer from it” (Dunning, 2011, p. 251) sheds further light on the complex relationship between knowledge and beliefs. For instance, Light et al. (2022) showed how groups with the least knowledge about controversial science issues have the most confidence in their knowledge. Examples include “whether genetically modified (GM) foods are safe to eat, climate change is due to human activity, humans have evolved over time, more nuclear power is necessary, and childhood vaccines should be mandatory” (p. 1). The converse to the problems of overconfidence are the benefits of well-earned confidence: people who are both knowledgeable and confident are better able to make sense of controversial science topics

than those who are knowledgeable but lacking in confidence. For instance, Peters et al. (2019) showed that people who have high “numeracy,” or numerical literacy, and high confidence levels are better able to cope with making sense of health situations imbued with data than those who are knowledgeable but lack confidence.

One explanation for the relationships between knowledge and confidence is motivated reasoning. For example, Radrizzani et al. (2023) found that trust in relevant sciences increased during the COVID-19 pandemic among adults in the U.K., but also became more polarized; those who reported lower trust in scientists prior to the pandemic reported that their trust in scientists had decreased over time, while those reporting higher pre-pandemic trust tended to report becoming more trusting over time, indicating that respondents pre-existing views were strengthened.

Developmental, Social, Dispositional, Psychological Factors

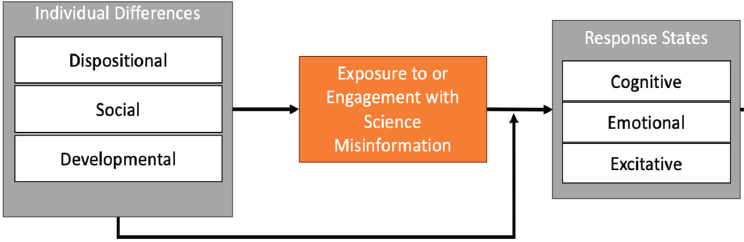

Theory borrowed from the study of media effects suggests that individual differences can influence effects of misinformation about science in two ways (see Valkenburg & Peter, 2013). First, individual dispositional, developmental, and social characteristics can predict exposure to and/or engagement with misinformation about science. Dispositional dimensions of receptivity1 to media effects are those individual characteristics that shape how people select and respond to media including gender, values, attitudes, beliefs, and motivations, among other elements (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013). We expand on some of these dispositional dimensions (e.g., prior attitudes and beliefs) below. Developmental factors can include those that shape media consumption in childhood as well as those in adulthood affected by life stage, such as childrearing. Though some studies have examined age or cohort as a possible individual difference variable in receptivity to science and/or health misinformation (e.g., Nan et al., 2022), the findings are somewhat mixed and limited across different contexts. This presents an opportunity for future research. Lastly, social characteristics include the interpersonal, institutional, and societal contexts that shape one’s receptiveness to misinformation about science. Individuals do not form attitudes or beliefs in a vacuum; social networks are crucial in understanding how beliefs are formed and spread and how they influence decisions (e.g., Frank et al., 2023; Henry, 2021). Furthermore, group identity and descriptive and injunctive norms have been shown to be influences on individuals’ “planned behavior” (e.g., Ajzen, 2020). Individual differences can moderate the possible response states triggered by exposure to and engagement with misinformation about science (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013; see Figure 6-2).

___________________

1 Valkenburg & Peter (2013) use the term “susceptibility.”

SOURCE: Based on Valkenburg & Peter, 2013.

People may believe misinformation because it fulfills their psychological needs to understand the world, to feel in control, or to feel connected to their community (Young, 2023a). Most of the existing research on such factors has focused on belief in conspiracy theories; however, in the committee’s view, these findings would be expected for other types of misinformation, though this should be explored in future research. For example, people who felt more uncertain about themselves, their place in the world, and their future were more likely to believe COVID-19 conspiracy theories (Miller, 2020), and belief in conspiracy theories is linked with greater need for uniqueness (Imhoff & Lamberty, 2017; Lantian et al., 2017). Conversely, reminding people about times when they have felt in control reduces belief in conspiracy theories (van Prooijen & Acker, 2015). As such, one might expect exposure to false narratives and belief in misinformation to correlate with improved psychological functioning as people are able to fulfill their psychological needs. However, current research suggests that those needs actually remain unfulfilled (Douglas et al., 2017).

Anxiety, such as the chronic anxiety that many experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic (Brown et al., 2023) is also associated with increased belief in conspiracy theories (Grzesiak-Feldman, 2013), and neuroticism is correlated with false rumors (Lai et al., 2020). In another study, people with higher scores on depression screening questionnaires were more likely to endorse misinformation (Perlis et al., 2022). And while it is unknown whether belief in conspiracy theories is a cause or consequence, it is associated with negative mental health symptoms (Bowes et al., 2021).

Science and Health Literacy

Science knowledge and science literacy are often used interchangeably in the literature, although science literacy tends to encompass broader features than knowledge about science, such

as cultural appreciation, recognition of expertise and personal dispositions, such as inquisitiveness and openness (National Academies, 2016b). Despite its commonsense appeal, the weight of the current evidence does not support a simple relationship between having higher science literacy and being more discerning between accurate and inaccurate information, more critical of dubious claims and sources, and more open to updating beliefs based on new evidence (see Box 6-1). Indeed, science literacy and cognitive competencies are often regarded as key factors for avoiding and resisting misinformation about science. But such an assumption mirrors the public deficit model, or the knowledge deficit hypothesis, which posits that public skepticism and negative attitudes toward science (or in this case openness to misinformation about science) are the result of a lack of public scientific literacy (Besley & Tanner, 2011; see Suldovsky, 2016). However, a large body of literature investigating the effects of knowing scientific facts, or of science literacy and literacy-adjacent cognitive competencies (e.g., critical reasoning ability, cognitive reflection, deliberation, knowledge calibration) on receptiveness to misinformation about science calls for a more nuanced understanding. For example, in some cases, there is a positive relationship between the tendency to use analytical reasoning and belief accuracy (Landrum et al., 2021; Pennycook & Rand, 2019). In others, there is no clear relationship: Attari et al. (2010) find that most people make the

same errors in estimating energy use from household appliances despite varying literacy levels. Moreover, some studies have found that individuals with greater science literacy and education have even more polarized beliefs than the less well-informed when it comes to controversial science topics, such as climate change, evolution, and stem cell research (Drummond & Fischhoff, 2017a).

Although a particular level of science knowledge or literacy does not solely explain receptivity to misinformation, when combined with other factors, the likelihood of individual receptivity to misinformation about science increases. Science literacy is an important competency that enables informed decision making; however, it also interacts with other factors, such as worldview, political orientation, religious affiliation, identity, values, emotions, and motivations, and this constellation of factors influence how people process and interpret science information (e.g., Kahan et al., 2012).

Other cognitive dimensions related to science knowledge and attitudes have also been suggested and tested empirically. Science curiosity (Kahan et al., 2012) and scientific reasoning (Drummond & Fischoff, 2015), for example, tap elements of literacy that are less factual and more process based. These have been found to be less predictive of polarized beliefs than fact-based measures of literacy.

In a related vein, health literacy is assumed to “enable individuals to obtain, understand, appraise, and use information to make decisions and take actions that will have an impact on health status” (Nutbeam & Lloyd, 2021, p. 161). While the definition does not explicitly address misinformation about health, the idea of an ability to obtain correct information and appraise information proposes a mechanism through which health literacy may play a role in how individuals are exposed to and influenced by misinformation. Some studies have also focused on understanding the role of so-called functional, interactional, and critical health literacy skills, which allow people to discriminate between sources of information and critically extract meaning and relevance for their situation and conditions (Nutbeam, 2000).

Sense of Agency and Identity as a Science Learner

Evidence is growing that a sense of agency and identity as a science learner, in both childhood and adulthood, increases individual capability, motivation, and likelihood to use science in a variety of settings (Avraamidou, 2022; Hinojosa et al., 2021; Polman & Miller, 2010; Shirk et al., 2012). Developing epistemic agency in science—shaping the knowledge and practice of science in their communities—is important for all learners (Stroupe, 2014), and especially for learners who need to combat structural barriers to their inclusion when they encounter it (Polman,

2023). Furthermore, such identification with science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) intersects with other identifications such as gender (Carlone et al., 2015; Steinke et al., 2024), race (Nasir & Vakil, 2017), or political views (Walsh & Tsurusaki, 2018). Positioning someone as capable in science, regardless of gender, race, or marginalized status, can help increase inclusion in STEM. Alternatively, positioning someone as incapable in science can lessen motivation and use (Brown et al., 2005; Sengupta-Irving, 2021). Research on conspiracy thinking also indicates that some communities seek to assert their epistemic agency by “doing their own research” (a common rhetorical tactic discussed in Chapter 5; Olshansky et al., 2020).

Detrimental Behaviors and Actions

Overall, researchers tend to find large consistent effects of misinformation on beliefs and much smaller effects on behavior (Adams et al., 2023; van der Linden et al., 2023). Partially, this is because behaviors (like getting vaccinated) are determined by multiple factors, which may or may not be related to beliefs (Hornik et al., 2020). For example, there are many people who are open to getting vaccines but cannot do so because of transportation or other logistical difficulties (Peña et al., 2023). Currently, most research to explore the link between misinformation, misbeliefs, and behavior has measured behavioral intentions (self-reported survey responses about what participants would likely do; Adams et al., 2023; Schmid et al., 2023). This is often due to resource constraints, but direct measures of behavior are particularly valuable and should be examined in future research.

Despite these limitations, misinformation can affect individual behavior in consequential ways. For example, belief in misinformation about cancer treatments may lead patients to make choices that increase their risk of death through delayed or lack of treatment, toxic effects, harmful interactions with other therapies, or economic harms (Johnson et al., 2022). Research in the United States from early 2021 (just after the first COVID-19 vaccines were approved) found that the amount of vaccine-related misinformation shared on Twitter by users in a region forecasted changes in vaccine hesitancy in that region 2–6 days later (Pierri et al., 2022). In addition, initial belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories predicted people’s actual vaccination behavior over the subsequent weeks or months in both the Netherlands and United States (van Prooijen & Böhm, 2023). Another study found that although online content flagged as misinformation on Facebook causally produced lower intention to vaccinate, few were exposed to this content; of more concern was the misleading content that was found to be more prevalent on mainstream media outlets and appeared to have an impact on behavioral intentions (Allen et al., 2024).

A recent meta-analysis of 64 laboratory-based RCTs examining the impact of health misinformation across the world found that none of these studies directly measured impacts on health or environmental behaviors. Approximately half of these studies indicated evidence for impacts on the psychological antecedents of behavior, including knowledge, attitudes, or behavioral intentions, as discussed above (Schmid, 2023). Several studies examined impact on trust, norms, and feelings, and the authors posited that the role of these factors in mediating the impact of misinformation warrants further study. They also noted a lack of diversity across different demographic groups in the samples of the studies they examined.

One example that illustrates this type of experimental work on the impacts of misinformation on behavioral intentions involved exposure to an anti-vaccine conspiracy theory. Exposure to such misinformation was found to decrease participants’ stated likelihood to immunize a fictitious child against a novel disease (Jolley & Douglas, 2014). Similarly, exposure to COVID-19 vaccine misinformation in September of 2020 reduced participants’ intentions to receive the vaccine (Loomba et al., 2021). However, when other participants were exposed to misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine in June of 2021 (after the vaccines had been in use for 6 months), the false headlines did not decrease vaccination intentions (de Saint Laurent et al., 2022). In addition, exposure to conspiracy theories about the human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV) led to decreases in intentions to get immunized, but only among participants with low prior knowledge about the vaccine (Chen et al., 2021). Thus, current research suggests that the effects of misinformation on behavior are likely to be greatest when people are first forming an opinion about a topic or issue. More research is needed to establish who is most likely to act on their misbeliefs associated with misinformation in harmful ways.

UNDERSTANDING HARMS AT THE COMMUNITY LEVEL

As Chapter 3 described, the phenomenon of misinformation about science is best understood through a systems perspective, where individuals are affected by the contexts in which they live and encounter (mis)information. Understanding the psychology of misinformation and how it effects individuals is important, but understanding potential for harm at the community level is important for understanding differential impacts on a larger scale and for informing solutions that do not place the onus solely on individuals. Below, we describe the structural factors that influence receptivity to misinformation and potentially lead to compounding harms. Of particular concern is misinformation that could lead to violent or threatening behavior.

Structural Factors Influencing Receptivity to Misinformation About Science

Individuals belong to various communities that are differentially situated with respect to health and science information in the information ecosystem, as described in Chapter 3. Additionally, there are broader cultural and societal factors that shape experiences, perceptions, and behaviors related to science and health information, and by extension, misinformation. The sections below describe in more detail the role of community- and societal-level factors such as socio-economic status, information access, marginalization, and racism in the effects of misinformation about science including how these factors contribute to differential receptiveness. Moreover, when communities are receptive to misinformation and it disrupts informed decision making, it can compound existing harms, such as the health disparities that many communities face due to poverty, racism, environmental degradation, and/or communication inequalities (Viswanath et al., 2020). Finally, it is important to understand when misinformation might be especially consequential and intervention warranted to prevent (further) harm, such as when communities are targeted with disinformation campaigns (Collins-Dexter, 2020).

Socio-economic Status

Stratification, whether measured in terms of income, education, occupation, or other measures of socio-economic status (SES), is central to any conversation about the study of effects of misinformation about science. Science and health literacy are not equally distributed throughout society. A review of several papers on health literacy concluded that downstream social determinants such as education, occupation, and income are associated with access to and acting on health information (Keen Woods et al., 2023; Stormacq et al., 2019). In fact, SES is strongly associated with holding accurate knowledge in areas such as science, health, environment and politics, and these SES-based knowledge gaps grow as information spreads more widely (Tichenor et al., 1980; Viswanath & Finnegan, 1996). These findings are particularly relevant to understanding misinformation’s effects in times of scientific uncertainty and fast-paced generation of scientific information.

By extension, several studies have shown associations between SES and exposure to and prevalence of misinformation. At the macro level, a study of survey responses from 35 countries noted that the lower a country’s gross domestic product (GDP; i.e., GDP per capita, a measure used to gauge a country’s total economic output) is, the greater the prevalence of COVID-19 misinformation (Cha et al., 2021). Similarly, a study with over

18,000 respondents across 40 countries also found an association between lower GDP and a high prevalence of COVID-19 misinformation (Singh et al., 2022). They also found that poorer countries were more likely to be exposed to and believe misinformation, and they showed higher rates of vaccine hesitancy than countries with higher GDP (Singh et al., 2022). Other national and global studies have shown associations between SES and health, and that low literacy is strongly correlated with low socio-economic and social standing (Buckingham et al., 2023; Sørensen et al., 2015). In one study, the authors examined eight European countries and found that, among these countries, SES is positively associated with health literacy skills (Sørensen et al., 2015). Several studies illustrate an association between health literacy and health disparities and risk perceptions (Berkman et al., 2011; Stormacq et al., 2019). Lower levels of health literacy are associated with structural barriers, such as lower levels of education and limited educational opportunities, policies and practices that are either discriminatory or not culturally tailored, and lower levels of trust in the healthcare system. These factors have been shown to limit access to resources and skills important to health literacy in some communities (Muvuka et al., 2020).

Information Access

As discussed in Chapters 3 and 5, communities vary in their access to reliable information about science. Some communities experience an overabundance of information (e.g., infodemics during public health emergencies), and others experience information voids (see Chapter 5). Further, there are relevant differences in the media preferences across communities (see Chapter 4), which may influence the type of information particular communities are more likely to encounter or consume (Soto-Vásquez, 2023). Importantly, some social media platforms have attempted to combat misinformation, such as by restricting vaccine-related content to only reputable sources, which, while reducing misinformation about vaccines, inadvertently created information vacuums (Guidry et al., 2020).

The issue of “digital inequalities” also affects different communities variably (Barnidge & Xenos, 2021). For example, rural areas face unique challenges (Perera et al., 2023; Vassilakopoulou & Hustad, 2021) with respect to equal access to reliable broadband internet, while urban areas experience “digital redlining,” the creation or furthering of inequity in marginalized geographical areas through inequitable access to technology (Popiel & Pickard, 2022). Such inequalities can limit the ability for some communities to participate in and understand a new and rapidly changing information society (Vassilakopoulou & Hustad, 2021), including the ability to discern and act upon reliable science information.

Marginalization and Racism

Misinformation’s impact on communities that have been marginalized because of race, ethnicity, nationality, or language must be understood within their broader socio-cultural and political context. Many of these communities are often treated as monoliths, but in fact are quite diverse in history, cultural contexts, language, socio-economic conditions, and patterns of trust—elements that matter for understanding the impacts of misinformation. Such homogenous labeling can also obscure specific disparities between these communities, which has implications for their relationship to information and also the impacts of misinformation about science. For example, the Latino community is composed of many distinct communities that shape how they interpret and experience harms. Cuban American communities differ in important ways from Mexican American communities, and there are variations even within those communities. The Asian American community includes people who speak over 50 languages (Asian American Disinformation Table, 2022). Likewise, African Americans belong to a broad and diverse population of Black people and people of African ancestry, who also have unique histories and cultures. This rich diversity can also provide sources of strength and resilience in the face of misinformation about science, not simply sources of vulnerability (Cabrera et al., 2022). Community-led strategies that demonstrate the resilience of these communities are discussed in Chapter 7.

Despite this resilience, long-standing educational, occupational, housing, wealth, and health disparities are well-documented across these communities. Health disparities, including the unequal prevalence of risk conditions, morbidity, and mortality, are deeply rooted in historical and current-day societal structures, and in the organization of institutions and practices. Structural racism, or the myriad ways in which social institutions and processes perpetuate discrimination, is an important factor in these unequal and harmful outcomes (Bailey et al., 2017). Its impact is evident in various health indicators, including kidney disease, HIV, cancer, and COVID-19. The historical legacy of structural racism fosters inequalities and fuels distrust among marginalized communities, who may justifiably question systems that have been exploitative and not designed for their benefit (Bonilla-Silva, 1997; Gee & Ford, 2011). Overall, few studies have paid sufficient attention to such communities, and more research is needed that explores the impacts of misinformation and the strategies that the communities themselves are developing to combat it (Soto-Vasquez, 2023). Therefore, analyzing the impact of misinformation about science necessitates a comprehensive understanding of these effects on individual, group, and population levels, considering various social institutions and the context of both historical and current inequities.

Some communities have had experiences in which misinformation about science was used to justify violence or disenfranchisement. This includes painful histories, such as the eugenics movement, where what was once considered the scientific consensus was determined over time to be misinformation that was based on racist, biased, and discriminatory research.2 Evidence suggests that these types of experiences among non-English communities may affect how they may perceive and believe science misinformation and disinformation. For example, misinformation and disinformation about Native and Pacific communities historically being used to justify land theft and occupation as well as ongoing displacement (e.g., the science of blood quantum logics to dispossess Native people from their homes [Arvin, 2019; Kauanui, 2008]); myths about Indigenous communities as “backwards” and “anti-science” (Smith, 1999); and erasures of violence such as nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands (Teaiwa, 1994).

Research shows that racialized discourses of disease have also been used to stoke anti-immigrant sentiments (Shah, 2001) and as justification for state-sanctioned measures of control, such as during the AIDS epidemic in the early 1990s (Paik, 2013). Racism against various groups has also been observed as a recurring theme in online misinformation about COVID-19 (Brennen et al., 2021; Criss et al., 2021). In particular, individuals of Chinese descent have been inaccurately scapegoated as carriers or creators of the disease (Holt et al., 2022; Kim & Kesari, 2021). This phenomenon may not be a coincidence—existing research suggests that conspiracy theories and prejudice may share the same underlying psychological characteristics, but this possibility has not yet been studied directly (Freelon, 2023). Box 6-2 illustrates how the phenomenon of misinformation about science can be differentially experienced in immigrant and diaspora communities.

Targeting

Some communities have also been the targets of misinformation and disinformation. For example, scholars report that the tobacco industry engaged in efforts to direct misleading information, such as through advertising, with devastating impact on Black, Latino, poor, homeless, and other marginalized and minoritized populations (Apollonio & Malone, 2005; U.S. National Cancer Institute, 2017). Menthol cigarettes were also reported to be heavily marketed toward defined audience segments, particularly African Americans (Anderson, 2011; Wailoo, 2021). Inaccurate information about vaccines and autism that targets Black people has also been deployed in the United States (see for example, Stone, 2021). Similarly, in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Vinck et al., 2019), the spread of

___________________

2 See https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/fact-sheets/Eugenics-and-Scientific-Racism

misinformation asserting that the outbreak of the Ebola virus was not real has been reported.

There is evidence that specific communities that have been targeted by anti-vaccine disinformation campaigns have higher rates of vaccine hesitancy, strengthening the link between misinformation and misbeliefs about vaccines. One prominent example is the Somali immigrant community in

Minnesota and the resulting outbreak of measles in 2017. The community was concerned that their children were being diagnosed with autism, a diagnosis that was rare in Somalia. Scholars report that anti-vaccine activist groups then targeted the community, spreading misinformation about the safety of childhood immunizations and promoting the false claim that the MMR vaccine causes autism (DiResta, 2018; Molteni, 2017). Immunization rates for young children of Somali descent in Hennepin County were later reported to have dropped from over 90% in 2008 to 36% in 2014 (Hall et al., 2017). The resulting measles outbreak infected 75 people before being contained (Minnesota Department of Health, 2017). A similarly sized measles outbreak in Washington state was estimated to cost ~3.4 million dollars in terms of the public health response, productivity losses, and direct medical costs (Pike et al., 2021), with others suggesting that even that cost is likely an underestimation (Cataldi, 2021).

Discrimination and Violence

Misinformation can also foster discrimination or violence. Some evidence exists that misinformation has led to violent destruction of infrastructure (Jolley & Paterson, 2020). Additionally, discrimination and violence against specific groups based on race or ethnicity warrant important consideration. Establishing a direct causal link between exposure to misinformation and subsequent increases in discrimination or violence is challenging, which likely contributes to the existing gap in the literature. Yet, the consequences of this potential connection are severe (Irfan, 2021). This is particularly true when that misinformation is propagated by elite individuals, and some recent studies have explored this issue within the context of COVID-19. For instance, Chong et al. (2021) identified an association between the spread of misinformation, disinformation, and historical stereotypes with an increase in racist attacks against Asian and Black individuals during the pandemic. Tessler et al. (2020) reviewed patterns of violence and discrimination against Asians and Asian Americans during the pandemic and suggest that the rise in such incidents against Asian individuals and businesses during the pandemic was linked to beliefs about the origins of and potential carriers of COVID-19. The authors also draw parallels between the anti-Asian sentiment during the pandemic and the anti-Arab and anti-Muslim sentiment following the 9/11 attacks, which extended beyond Arabs and Muslims to also affect Sikhs, Indian Americans, Lebanese, and Greeks (see Perry, 2003). Kim & Kesari (2021) argue that both the spread of misinformation and increasing patterns of violence toward Asians and Asian-Americans can be traced back to rhetoric by elite individuals that more closely resembles hate speech misinformation. However, they suggest further research is

needed to explore the intersections between hate speech, violence, and misinformation (Kim & Kesari, 2021).

CONSEQUENCES OF MISINFORMATION AT THE SOCIETAL LEVEL

The consequences of misinformation about science at the societal level are challenging to measure, given the multiple factors involved and the interrelated nature of those factors. Furthermore, some societal harms are most consequential in the ways that they amass over time, as with misinformation associated with the addictiveness of opioids. Many studies of societal-level impacts of misinformation have focused on political contexts, such as effects on elections. Some of this literature with particular relevance to misinformation about science includes research on the effects of misinformation on: trust in institutions; collective decision making; public health; and the scientific enterprise.

Effects on Trust in Institutions

Scholars have argued that misinformation can erode trust in institutions, including science and the media, especially when that misinformation takes the form of conspiracy narratives related to authorities and institutions (e.g., see Hofstadter, 1964; Rutjens & Većkalov, 2022; van der Linden, 2015). For instance, exposure to untrustworthy news sources has been linked to a decrease in trust in mainstream media over time (Ognyanova et al., 2020). Similarly, reading about COVID-19 conspiracy theories has been shown to reduce participants’ trust in institutions and diminish support for government regulations (Pummerer et al., 2022).

The causal direction of the relationship between exposure to conspiratorial misinformation and low trust in institutions remains unclear. Belief in conspiracy theories is strongly predicted by pre-existing mistrust in authorities and institutions (e.g., Abalakina-Paap et al., 1999; Einstein & Glick, 2015; van Prooijen et al., 2022b), suggesting that the connection between exposure to such kinds of misinformation and low institutional trust may be more complex or iterative. Further research is needed to explore the relationship between misinformation and trust in institutions, particularly to clarify the directionality and potential feedback mechanisms involved.

Many individuals rely on mainstream media sources for their information about science (Funk et al., 2017; National Science Board, 2024). Given the reach and potential impact of mass media, it is important to examine how misinformation about science might have consequences for the media. As discussed in earlier sections of this chapter, exposure does not equate to attention to or belief in that information. However, some

evidence does exist that misinformation affects trust in journalism. Media coverage of misinformation may inadvertently increase the repetition of the misinformation, or lead to second order effects, such as increased feelings of cynicism, apathy, disengagement, or unhealthy levels of skepticism of all information, both accurate and inaccurate (Guess & Lyons, 2020). Further, in one experiment, participants who read tweets about fake news were more distrustful of news media and less likely to correctly label accurate news stories as real as compared to participants who read tweets about the federal budget (Van Duyn & Collier, 2019). Scholars also find some evidence that “fake news” websites influence the issue agendas of partisan media online (Vargo et al., 2018).

Collective Decision Making

Some misinformation, whether intentional or unintentionally produced, can stymie having a shared set of facts around which to debate policy options. Public debates about policy-relevant science topics that are also primed for misinformation have been affected by disputes over evidence, as well as by well-organized campaigns to spread false claims, increase doubt, and mischaracterize the state of science (see Chapters 4 and 5). Some scholars have expressed particular concern that political polarization around scientific topics is increasing, such that there are fewer shared epistemologies for what constitutes reliable evidence for claims (Lewandowsky et al., 2017, 2023). Others have argued that disputes over agreed upon facts and policy options have long existed (Nyhan, 2020), and that such facts can still be productively debated (Judge et al., 2023).

Misinformation that disrupts the ability for scientific evidence to inform productive decision making at different levels of government (local, state, national) is potentially harmful simply by virtue of the scale of potential influence. As described in Chapter 3, science plays a unique role in society because it provides a reliable way to describe the current status of an issue, determine potential causes and influences, and estimate risks and predict the likely outcomes of different choices. However, it is important to underscore that scientific evidence alone is not sufficient for making individual and policy choices, particularly in cases where scientific uncertainty may be high (e.g., new technologies). Decades of work in the social sciences dispute simple models of people as rational actors who dispassionately weigh facts to make choices (Dietz, 2023). Similarly, evidence from the science of science communication clearly demonstrates that simply providing facts, regardless of how accurate, accessible, and understandable the information is, will not automatically lead to courses of action that are in accordance with what scientists believe they should be (National Academies, 2017). But despite these limitations, misinformation about science that disrupts

the ability to discern reliable information from science for use in decision making has great potential for harm.

Public Health and Medicine

Some of the most consequential societal effects of misinformation about science have been documented within public health. Disinformation campaigns have been linked to decreased vaccination rates and delayed rollouts of beneficial public health campaigns. The link between misinformation and vaccine hesitancy has been demonstrated in both observational longitudinal studies and case studies of specific communities. For example, Wilson & Wiysonge (2020) examined the link between disinformation campaigns about vaccines and actual vaccination rates across 166 countries. They found that a one-point increase in the five-point disinformation scale was associated with a two-percentage point drop in average global vaccination rates year on year. Such a lack of vaccine demand during the pandemic likely had tragic consequences. Some have estimated that between 178,000 to over 300,000 American lives could have been saved with higher COVID-19 vaccination rates (Zhong et al., 2022).

Misinformation can also harm public health when it delays the implementation of beneficial interventions. For example, the delayed rollout of antiretrovirals in South Africa as a treatment for AIDS was reported to, at least in part, be due to government officials’ promulgation of medical misinformation (Baleta, 1999; MacGregor, 2000), and is estimated to have cost more than 330,000 lives (Chigwedere et al., 2008). Similarly, Golden Rice, a genetically-modified crop designed to reduce vitamin A deficiency, was first developed in the 1990s and has yet to be widely adopted due to concerns over genetically-modified organisms (GMOs) and prominent misinformation campaigns (Wu et al., 2021). Meanwhile, vitamin A deficiency is reported to be a major health problem affecting 29% of children between six months and five years of age in low- and middle-income countries (as of 2013) and contributes to preventable blindness and increased mortality from measles and diarrhea (Stevens et al., 2015).

Misinformation about science may also have direct and indirect impacts on clinical care. Prior to the pandemic, burnout among healthcare practitioners was high and rising. Additional qualitative research suggests that clinicians may feel ill equipped, untrained, and lacking sufficient time to adequately address medical misinformation either at the point of care or online (Amanullah & Ramesh Shankar, 2020; Leo et al., 2021; Sharifi et al., 2020). Some clinicians were also reported to have experienced moral distress treating critically ill patients who had chosen not to receive a COVID-19 vaccine (Klitzman, 2022). While it is not clear what impact medical misinformation is having on healthcare workers, levels of burnout,

and, therefore, patients, this intersection will continue to be an important area of study.

The Process of Science

The presence of misinformation may also alter scientific priorities, funding for science, and the ways that scientists communicate. In areas where misinformation is rampant (e.g., climate change), researchers are forced to spend time and energy combating false beliefs rather than producing new knowledge. As one example, Lewandowsky et al. (2015) argue that claims that opposed scientific agreement around climate change, such as that global warming had paused, led to a large number of research papers and reports rebutting or providing further context on that claim (including two special issues in Nature journals and a large section of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s AR5 report) despite the “pause” only existing when trends are calculated starting in one specific abnormally warm year. Similarly, Wakefield et al.’s discredited study (1998) that asserted a link between autism and the MMR vaccine was reported to have changed scientific priorities and led to multiple new studies, meta-analyses, and expert panel summaries all finding no link between vaccines and autism (e.g., Institute of Medicine, 2004; Jain et al., 2015; Madsen et al., 2002; Pietrantonj et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2014).

In addition, science knowledge, science interest, and trust in science are correlated with public support for government funding for science (Besley, 2018; Motta, 2019). Thus, if exposure to misinformation reduces science knowledge, interest, or trust, public support for science and science funding may decrease. As mentioned above, there is some evidence that misinformation can decrease accurate knowledge and trust in institutions, but there is a lack of research examining the direct costs of misinformation on public support of science.

SUMMARY

Understanding the consequences of misinformation about science requires a systems perspective. Misinformation has the potential to directly and/or indirectly harm individuals, families, communities, and society. The strongest evidence of harm supports the argument that misinformation can cause misbeliefs, which is an important potential harm in the committee’s view because it disrupts individual agency. While most research to date has focused on how misinformation affects individual beliefs, knowledge, and attitudes, less evidence exists for how misinformation leads to detrimental behaviors, and most of this research has measured behavioral intent. Nevertheless, some effects on behavior are consequential for well-being,

particularly when the consequences are severe, when they affect people who are already experiencing harm, or when they happen at scale through targeted campaigns and elite amplification. Of particular concern, there is also evidence showing that the consequences of misinformation about science are differential across class, language, race/ethnicity, and place, as well as where these intersect, and that the effects on individuals are influenced and shaped by structural and cultural contexts of their lived experiences, access to material and social resources, and community embeddedness of their social lives. These connections warrant further study. Some evidence suggests that there may be important consequences of misinformation at the societal level by contributing to declining levels of healthy trust in institutions, affecting public health at scale, impeding productive discussion and collective decision making, and shaping the process of science itself. These societal-level consequences have been more difficult to establish empirically but remain an important area of study.

Conclusion 6-1: Many historically marginalized and under-resourced communities (e.g., communities of color, low-income communities, rural communities) experience disproportionately low access to accurate information, including science-related information. Such long-standing inequities in access to accurate, culturally relevant, and sufficiently translated science-related information can create information voids that may be exploited and filled by misinformation about science.

Conclusion 6-2: Most research to date on misinformation, including misinformation about science, has focused on its relationship to individuals’ knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behavioral intentions. Some research has examined the impact of misinformation on behavior. From this work, it is known that:

- Misinformation about science can cause individuals to develop or hold misbeliefs, and these misbeliefs can potentially lead to detrimental behaviors and actions. Although a direct causal link between misinformation about science and detrimental behaviors and actions has not been definitively established, the current body of existing evidence does indicate that misinformation plays a role in impacting behaviors, that in some cases, results in negative consequences for individuals, communities, and societies.

- Individuals are more receptive to misinformation about science, and, consequently, most affected by it, when it aligns with their worldviews and values, originates from a source they trust, is repeated, and/or is about a topic for which they lack strong preexisting attitudes and beliefs.

- Science literacy is an important competency that enables informed decision making but is not sufficient for individual resilience to misinformation about science.

Conclusion 6-3: Many individual-level factors such as personal values, prior beliefs, interests, identity, preferences, and biases influence how individuals seek, process, interpret, engage with, and share science information, including misinformation. Social factors, including race, ethnicity, socio-economic status, culture, social networks, and geography also play a critical role in affecting information access. This constellation of factors shapes an individual’s information diet, media repertoires, and social networks, and therefore may also determine how much misinformation about science they encounter, the extent to which they engage with it, and whether it alters their beliefs.

Conclusion 6-4: The accuracy of the science information people consume is only one factor among many that influences an individual’s use of such information for decision making. Even when people have accurate information, additional influences can lead them to make decisions and engage in behaviors that are not aligned to the best available evidence. At the individual level, these include their interests, values, worldviews, religious beliefs, social identity, and political predispositions. At the structural level, access to material and social resources such as healthcare coverage, affordable nutritious food, internet connectivity, and reliable transportation among others may play a particularly important role.

Conclusion 6-5: Misinformation about science about and/or targeted to historically marginalized communities and populations may create and/or reinforce stereotypes, bias, and negative, untrue narratives that have the potential to cause further harm to such groups.

Conclusion 6-6: Overall, there is a critical need for continuous monitoring of the current information environment to track and document the origins, spread, and impact of misinformation about science across different platforms and communication spheres. Such a process, like monitoring for signals of epidemics, could better support institutions and individuals in navigating the complexities of the current information ecosystem, including proactively managing misinformation about science.

This page intentionally left blank.