Understanding and Addressing Misinformation About Science (2025)

Chapter: 3 Misinformation About Science: Understanding the Current Context

3

Misinformation About Science: Understanding the Current Context

Addressing a gathering of media professionals and researchers in the late 1940s, Hugh Beville, then director of research for NBC, spoke about the “challenge of the new media” and noted that “America is now entering a new era of electronic mass communication. These new vehicles of electronic communications will have a tremendous impact on all existing means of mass communication” (Beville, 1948, p. 3). Even earlier, Dewey (1923, p. 127) noted the impact of new technologies—the “telegraph, telephone, and now the radio, cheap and quick mails, the printing press, capable of swift reduplication of material at low cost”—to the challenge of conveying accurate information to the public for democratic participation. Those words of caution just as easily could have been written by a social science researcher in recent years. While the technical and socio-cultural dimensions of change and opportunity in the early decades of the 21st century differ from the 20th century, the collective consternation and wonder regarding changes in our information ecosystem has been relatively consistent.

The aim of the present chapter is to describe the broader contexts within which the phenomenon of misinformation about science emerges and impacts society. To more fully understand the production and spread of misinformation about science (Chapter 4 and 5), what consequences it has for individuals, communities, and for society as a whole (Chapter 6), and what can be done to counter or minimize its negative impacts (Chapter 7), it is important to understand that these phenomena do not occur in a vacuum. Rather, individuals, the communities they are a part of, and their information ecosystems are all shaped by larger societal forces. These include

changing demographics in the United States (Vespa et al., 2020) as well as other larger shifts currently shaping American society, including declining trust in institutions, political polarization, racial and socio-economic divides, and other forces that shape how people are positioned relative to science and the science information environment. These forces influence, for example, to what extent and in what ways individuals and communities interact with science and scientific (mis)information, how people interpret and use (or ignore) misinformation about science, and the role that misinformation may play in shaping societal decision making.

Subsequent sections of this chapter describe two factors of contemporary American society that are particularly salient for understanding the phenomenon of misinformation about science in the view of the committee: (a) patterns of trust and confidence in institutions (including science) and their intersection with political polarization and (b) structural and systemic inequities. Next, we describe changes in the information ecosystems people inhabit, and the relevance of these changes for understanding misinformation about science. Finally, the chapter concludes with a focus on specific elements of the science information environment that inform understanding of the spread and impacts of misinformation about science, and potential solutions. One element that we leave for future chapters is regulation. Although discussed throughout the report, we pay special attention to this topic in Chapter 7, where we discuss interventions for addressing misinformation about science.

SYSTEMIC FACTORS THAT SHAPE HOW PEOPLE INTERACT WITH INFORMATION

A large constellation of societal systems and forces shape whether and how people encounter information, perceive it, make sense of it, and decide how it informs their actions in the world. This chapter elucidates the need for understanding these phenomena through a systems perspective and describes relevant factors for understanding how people and communities are differently situated with respect to information about science (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [National Academies], 2016b). Communities of shared identity, geography, and affiliation can vary in how likely they are to seek out or to be exposed to information from science, accurate and otherwise; in what sources people seek, trust, and believe; and in the ability and tendencies to act on scientific information. Communities are also affected by social, legal, and political forces that shape society. Importantly, communities and society as a whole are affected by profound technological shifts shaping the information environment. These forces (both historical and contemporary, static and changing) inform this broader systemic way of understanding the phenomenon

of misinformation about science. As described in some detail below, there are numerous facets or dimensions that make up the “broader context,” including but not limited to: the historical and contemporary nature of the science-society relationship; structural inequalities; and declining trust and confidence in traditional institutions, including deepening political polarization. The way that individuals perceive and process information within this broader context is discussed in detail in Chapter 6 which focuses on the impacts of misinformation about science.

The Role of Science in Society

The role of science in society affects understanding of the broader context that shapes the phenomenon of misinformation about science. First, public access to accurate information from science has long been recognized as important for informing rational public deliberation and decision making in democratic societies (Bächtiger et al., 2018; Dewey, 1923; Habermas, 1970). The scientific method is generally viewed as a reliable, and thus a trustworthy, process for gaining knowledge about an increasingly complex world beset by multifaceted problems (e.g., environmental degradation, public health threats). However, decisions on matters concerning science are based not only on accurate facts but also on the values people use to make choices and to manage risks particularly under conditions of uncertainty (Dietz, 2013; NRC, 1996, 2008). Balancing between the two is challenging in the best of times (Pamuk, 2021; Rosenfeld, 2018), but misinformation can disrupt the exchange of reliable information that results uniquely from the scientific process. Healthy linkages between experts in the scientific community, the public, and decision makers—needed in democratic societies—can help ensure that these exchanges “get the science right” and “get the right science” (NRC, 1996).

Additionally, science has long held significant authority and legitimacy in society, and in the United States, this authority confers significant social power, including over consequential decisions that policymakers and other leaders make. The cultural authority of science also confers power to those who use its language, whether legitimately or not. Recognizing the cultural weight that scientists and scientific information carry is important for understanding why and how misinformation about health and science can similarly carry significant implications for individuals, communities, and societies, and why power dynamics are an important context for understanding both the problem and potential solutions. These dynamics also underscore why misinformation that arises from fraud or other misconduct within the scientific community can be more consequential than misinformation from other sources (see Chapters 4, 5, and 6 for further discussion).

Structural Inequalities

Long-standing structural inequalities within American society, including systemic racism, discrimination, and bias, intersect with and exacerbate problems of misinformation in complex and multi-faceted ways. Inequalities that stem from differences in socio-economic status or position, education level, race or ethnicity, primary language, or geography are consequential for economic, social, and physical well-being (Braveman & Gottlieb, 2014). In addition, many communities experience the effects of other areas of underinvestment (e.g., Satcher, 2022) that have the potential to compound the effects of disparities in access to and ability to act upon high-quality information from science.

In the committee’s view, several contexts are instructive for understanding how structural inequalities and misinformation about science intersect:

- Structural inequalities affect access to high-quality information from science.

- Many communities have experienced being the subjects of misinformation by the scientific community.

- The language of science has been used to conflate disease with immigrants.

- Experiences with past and current medical and environmental racism sow distrust and create opportunities for those who seek to exploit them to propagate misinformation.

Structural inequalities affect how individuals and communities are positioned with respect to high-quality information from science and misinformation (e.g., Viswanath et al., 2021). In particular, communities that have histories of being marginalized and under-resourced experience disparities in access to quality information about health and science, whether due to material circumstances, information vacuums, language barriers, or other factors (Viswanath et al., 2022b). For example, systemic inequalities result in people of lower socio-economic status and people in rural settings having less available, affordable, and reliable broadband internet access (Viswanath et al., 2012, 2022b; Whitacre et al., 2015), though there are other factors that shape demand for these services.

One effect of these experiences is that they shape what sources of information about science people trust, believe, and use. A recent study by the Pew Research Center (2024c) examined mistrust in institutions among Black Americans. This survey found that nearly 90% of Black Americans reported encountering inaccurate news in the media about Black people, and most of those respondents believed that those inaccuracies were intentional. Mistrust or reduced access to high-quality sources of information

presents a double penalty for such communities, which may need to seek out alternative sources of information that, in turn, encourage greater distrust of scientific institutions. For example, Druckman et al. (2024b) demonstrate the enduringly higher distrust of science by women and/or by people who are Black, of lower socio-economic status, or from rural communities. Other studies have pointed out a need for a greater research focus on particular communities, including the Latino community, to understand how factors like language, values, and identity among other factors shapes how misinformation is encountered, perceived, and/or acted upon (Lewandowsky et al., 2022; Soto-Vasquez, 2023). Understanding how the lived experiences of people within these groups inform trust in scientific information and receptivity to misinformation is important for discerning which interventions may be warranted (i.e., changes in practice and policy rather than persuasion).

Second, when misinformation about particular communities conforms to existing power structures, it may be more likely to be perceived as factually accurate and accepted as true, with negative consequences for the dis-empowered; see, for example, Gould (1996), which provides an extensive discussion of how commentators have drawn on scientific discourse based upon misinterpreted or biased measurements to support racist theories and policies for decades. Other narratives associating immigrants with criminality are false (Ousey & Kubrin, 2018), but have persisted (Soto-Vasquez, 2023). For example, throughout U.S. history, policymakers and other authorities have employed the language of medicine (a part of the existing power structure) to conflate disease and illness with immigrants and foreigners (Markel & Stern, 2002). By contrast, a society may regard claims as misinformation, subject them to doubt, or simply ignore them, if they are not consistent with dominant power relations, while privileging claims that enforce these power relations (Kuo & Marwick, 2021).

Black Americans in particular have been subject to a long and ongoing history of medical racism dating back to slavery, including medical experimentation, disparities in access to treatment and care, and prejudice in medical decision making (Gamble, 1997; Institute of Medicine, 2003; Nuriddin et al., 2020). Experiences with medical racism, contextualized within broader histories of violence and oppression, contribute to inequality-driven mistrust in science and medical institutions among Black Americans, which can foster resistance to evidence-based communication and provide fertile ground for misinformation (Jaiswal et al., 2020). For example, misinformation narratives that resonate with the collective memory and lived experiences of trauma and discrimination—e.g., that HIV/AIDS or COVID-19 are genocidal plots against communities of color—have circulated widely in Black communities (Collins-Dexter, 2020; Heller, 2015). Fears of medical racism and other community-specific concerns are

likewise exploited as the basis of contemporary disinformation campaigns targeting communities of color (Diamond et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2023). Experiences with environmental harms have also contributed to mistrust of science around topics such as water quality (Carrera et al., 2019), sanitation (Flowers, 2020), and disaster resilience and response (Bullard, 2008).

Inequities are also embedded in, and thus provide critical context for, efforts to curb misinformation about science. For example, technology companies have been slow to address misinformation on their platforms, particularly that which circulates among communities of color, and without adequate cultural knowledge about these communities and their information practices, platforms are ill-equipped to intervene effectively (Collins-Dexter, 2020). Similarly, platforms’ efforts to monitor and flag misinformation in the United States tend to prioritize misinformation in English, and high-quality public health information is rarely translated; together, this creates information voids among non-English speaking communities (Bonnevie et al., 2023).

What these intersections of inequity and misinformation make clear is that the problem of misinformation about science cannot be disentangled from the legacy of racism and ongoing systemic inequalities in the United States. Approaches to understand and address misinformation (as discussed in Chapter 7) therefore require attention to these inequalities and their impacts, as well as to communities’ historical and current experiences with racism and injustice.

Declining Trust in Institutions

Significant declines in Americans’ trust and confidence in various institutions of civic life are also relevant to understanding the phenomenon of misinformation about science (Brady & Schlozman, 2022). Trust is defined as the willingness of an actor to depend on and make themselves vulnerable to another entity (Schilke et al., 2021). Trust matters because it affects whether citizens are willing to rely on an institution for information to make decisions.

Particularly for politicized scientific topics, such as climate change, people are more likely to make choices about who and what sources they deem credible based on perceived common interests or shared values (Lupia, 2013). The decision whether to get vaccinated, for example, depends in part on whether one believes the findings from medical science about the perceived benefits, costs, and risks of a vaccine (Jamison et al., 2019b; Larson et al., 2011). Trust in science will affect whether one believes information from the scientific establishment and will affect the quality of sources of information someone consults (e.g., Perlis et al., 2023).

It is important to note that trust in science is not the same as knowledge about scientific facts or knowledge about scientific processes, although

researchers have found evidence of some relationships between various concepts, e.g., knowledge of science as a process predicts confidence in scientists to act in the best interests of the public (National Science Board, 2024). A considerable body of research on non-experts’ scientific reasoning suggests that there is not a simple, consistent relationship between, for example, trust in science or science literacy, and using scientific information to inform decision making (Drummond & Fischoff, 2017a, 2020). This is in part because these factors interact with other individual-level differences (e.g., worldviews, identity, motivations, risk tolerance) to shape both how people interpret and subsequently use (if at all) such information when making consequential decisions. In addition, many researchers who investigate public perceptions of science have drawn important distinctions between one’s ability to correctly identify scientific facts (e.g., Earth orbits the sun) and one’s belief that the interests of scientists are aligned with one’s own interests and the interests of one’s community, or that scientific institutions are trustworthy (e.g., Brossard & Lewenstein, 2010). This further highlights the conditional nature of the relationships among trust in science, scientific reasoning, exposure to science-related information, and decision making (Drummond & Fischhoff, 2020).

Below, we further discuss three areas related to trust: trust in scientific institutions specifically; how political polarization impacts trust in science; and trust in other civic institutions. An additional nuance to consider around how this phenomenon is measured concerns whether surveys assess trust in the institution of science, trust in science-producing institutions like universities, or trust in scientists. It is also important to note that many surveys that assess trust and confidence trends often underrepresent some communities and populations, such as people from low-income households and people of color (Lee & Viswanath, 2020; Viswanath et al., 2022a). In Chapter 6, we discuss how exposure to misinformation within the contexts of these broader trends impacts individuals, communities, and society, and in Chapter 7, we discuss strategies for increasing trust in sources of credible science information, including institutions.

Trust in Scientific Institutions

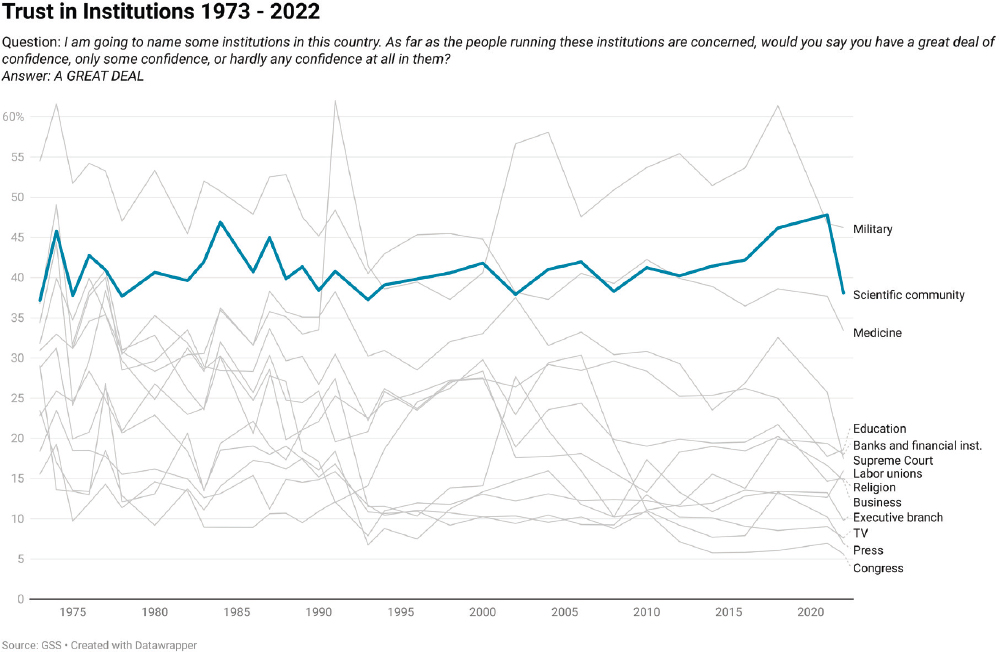

Trust in science and confidence in scientific institutions to act in ways aligned with public interest have fared better than has trust in most institutions over the last several decades (Brady & Kent, 2022; Krause et al., 2019), though they have not been immune to the fluctuations observed across all institutions and sectors, and there are conflicting signals about whether trust and confidence have been in decline over the last decade. Figure 3-1 shows how trust in the scientific community has fared over the last 50 years (1973–2022), as measured by the General Social Survey (GSS). As the figure

SOURCE: Committee generated using data from NORC’s General Social Survey Data accessed from the GSS Data Explorer website at gssdataexplorer.norc.org.

illustrates, the scientific community has been consistently one of the most trusted institutions in the United States. Further, while most institutions have suffered a major decline in trust during this period, the scientific community has enjoyed a steady level of public confidence during the past five decades, although with a notable drop from a near-high point of 48% in 2021 to a near low 38% in 2022. Other survey data suggest a significant recent decline in trust in science. The Pew Research Center (2023a) found that in 2019, 73% of U.S. adults believe that science has had a “mostly positive” effect on society; this had dropped to 57% by 2023 (with most of this drop occurring after February 2021, which roughly aligns with the drop as reported in the GSS data). Open and important questions when aligning these data sources are whether this recent drop in trust in science will be enduring; and if enduring, whether it has effects on where people get scientific information and on receptivity to misinformation about science.

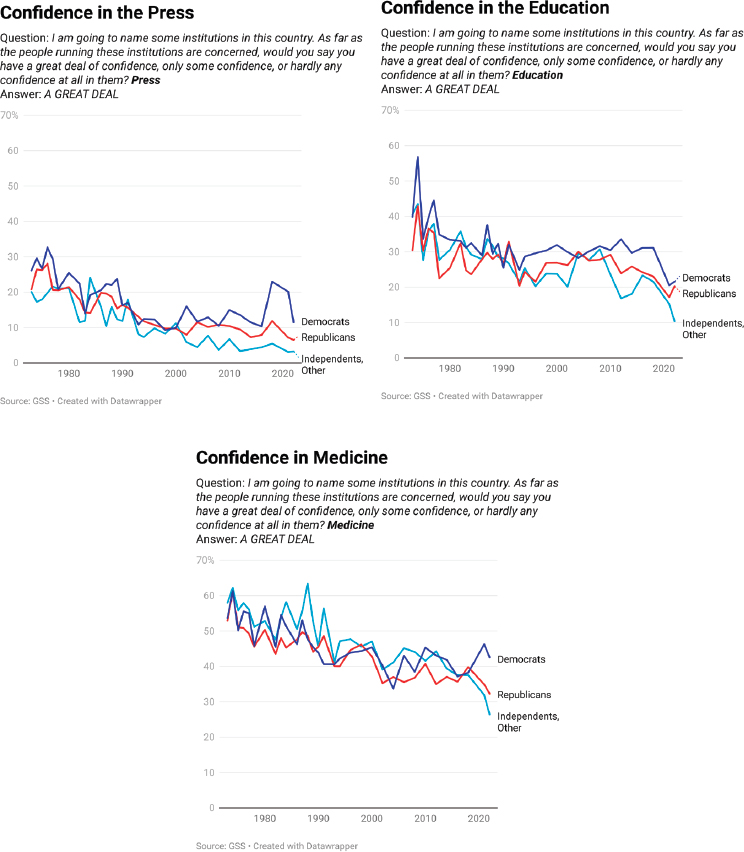

Since the 1970s, there has been an unambiguous drop in levels of trust in specific institutions that are involved in the production of scientific knowledge. The percentage of people expressing a lot of confidence in medicine has plummeted from a high point of 62% in 1974, to an all-time low point of 33% in 2022; education from a high point of 49% in 1974 to just 19% in 2022; and major companies (the source of much science) from a high of 31%, last reached in 1987, to 15% in 2022. Thus, while confidence in the scientific community in the abstract has remained fairly constant, institutions that produce science-based information have seen much larger declines in confidence over the last 50 years. This variation in trust in the various institutions that produce science in turn may drive which scientific findings are trusted by whom (Pechar et al., 2018).

Public perception of science also comprises various dimensions, and not all perceptions of science move in lockstep. The notion that scientific innovation might disrupt social stability in an unwelcome way appears to have increased in the United States in recent decades, for example. Between 2014 and 2022, roughly half of respondents on the GSS agreed or strongly agreed that “science makes our way of life change too fast,” an average increase of nearly 10% from levels reported from 1995 to 2012 (National Science Board, 2024). Public perceptions can also vary across various scientific fields and domains and across time. According to data reported for the 3M State of Science Index survey, for example, more people reported thinking “a lot” about the impact of science on their everyday lives in summer 2020 than was the case in fall 2019, likely because of the emergence of COVID-19 (National Science Board, 2024). Perceptions of the trustworthiness of research on different topics can vary as well. For example, perceptions of the trustworthiness of self-driving vehicles appear to change as people gain experience with these vehicles (Tenhundfeld et al., 2020). Despite general confidence in science and scientists in the United

States, it is important to note that public perceptions of novel and emergent research may differ from more established topics and that people may not consistently view all topics of scientific inquiry as equally the purview of “science” broadly considered.

Political Polarization and Trust in Science

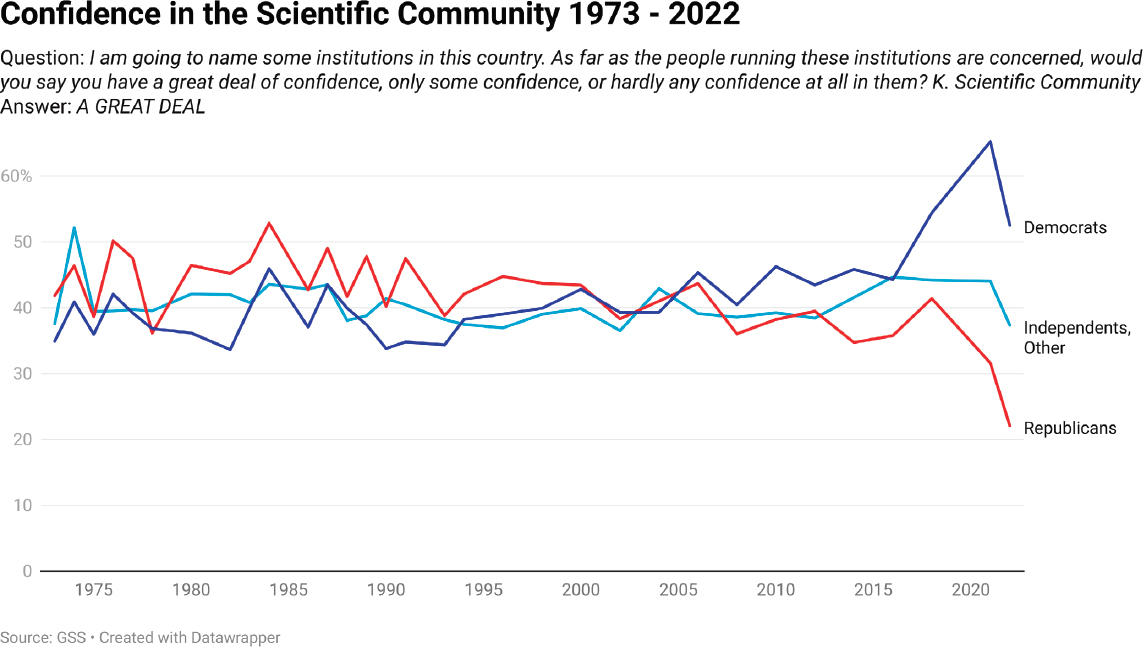

This apparent steadiness in confidence in scientific institutions also obscures the emergence of a large partisan and ideological divide in the last generation. Polarization has been conceptualized as the clustering of opposing opinions into two groups, where shared opinions become the basis on which groups identify and interact with each other (Judge et al., 2023). Opinions from elites can further contribute to the tendency of people within polarized groups to associate only with those who share their opinions and avoid those with different views, particularly those who are more politically active or who hold more extreme views (Judge et al., 2023). Cognitive processes can also contribute to polarization. For example, as people encounter information that both supports and counters their existing opinion, they may make sense of that information in ways that serve to reinforce or strengthen their original opinion. Generally, from 1973 to 2000, substantially more Republicans indicated they had “a great deal” of confidence in science than Democrats or Independents (Figure 3-2). In the period from 2000 to 2006, confidence in science was roughly equal across all three groups (Figure 3-2). However, between 2008 and 2022, there has been a widening gap in trust in science by partisan identity, with 53% of Democrats, for example, indicating a lot of confidence in science as of 2022, and 22% of Republicans indicating this same level of confidence (Figure 3-2). Notably, the percentage of Republicans indicating a great deal of confidence in science has dropped by nearly half since 2018 (Figure 3-2). Gauchat (2012) identifies a similar but significantly earlier trend with respect to political ideology (e.g., conservative, liberal, or moderate). Additionally, a similar trend with respect to educational and medical institutions has been observed, with an overall decline in trust in both institutions across the political spectrum since 2018, and in some cases, there are notable gaps by political ideology (Davern et al., 2024; see Figure 3-3).

Affective polarization—increased animosity toward an opposing group/party versus affinity for one’s own—has also shown a marked increase in recent years (Druckman et al., 2021; also see Jost et al., 2022). This increased animosity reinforces (and is reinforced by) trends toward fewer shared agreed upon facts and approaches to understanding the world (Jenke, 2023; also see Druckman et al., 2024a). For example, polarization increases the likelihood that people will accept new information that conforms with pre-existing beliefs and commitments more readily than that which challenges

SOURCE: Committee generated using data from NORC’s General Social Survey Data accessed from the GSS Data Explorer website at gssdataexplorer.norc.org.

those commitments (Jenke, 2023; Su, 2022). Political polarization may differ by topic, and a recent review suggests actual polarization around environmental issues may be less than people perceive them to be (Judge et al, 2023). Further, trust in individuals—scientists or doctors—may also differ from trust or confidence in the institution of science overall, including among the Black and Latino communities (Pew Research Center, 2022, 2024b), across a range of scientific topics.

Although partisanship and political ideology are sources of polarization, other beliefs may play a role in ideological divides. Patterns of science skepticism can vary by topic (e.g., climate change versus vaccines) and are affected by beliefs that are more nuanced than political partisanship. For example, science skepticism has been shown to be predicted by religiosity, social identity, and worldviews (e.g., individual freedom), which are not solely held by people of one political party (Rutjens et al., 2021). Other scholars have also found that focusing on partisan identity alone to explain differences in trust in science may obscure important nuances in how ideological beliefs and views about science intersect (McCright et al., 2013). Chapter 6 provides a more complete discussion about how these factors intersect to shape individual beliefs related to science information and the likelihood of holding misbeliefs associated with misinformation.

Trust in Other Civic Institutions

In contrast to trust in science and scientists, trust and confidence in other key institutions such as the press, media, and education has dropped, in some cases precipitously. Most notably, while 28% of Americans indicated a great deal of confidence in the press in the 1976 GSS, this number dropped to 7% in 2022 (see Figure 3-1), where 11% of Democrats and 3% of Republicans indicated a lot of trust in the press (see Figure 3-3). This has potentially invited or encouraged people and communities to seek out information about many issues or topics (including scientific and health-related ones) from a broader set of sources than they may have in the past. At the same time, declining societal trust in and reliance on some traditional sources of authority may be creating further openings for misinformation about science (and health) to spread more rapidly as people seek out ways to make sense of an increasingly complex world.

Societal Forces That May Warrant Further Study

As scientists seek to better understand the changing patterns in trust in institutions overall, other social and societal factors may warrant further study. The role of values is one such factor (see Sagiv & Schwartz, 2022

SOURCE: Committee generated using data from NORC’s General Social Survey Data accessed from the GSS Data Explorer website at gssdataexplorer.norc.org.

for a detailed review of personal values). In the United States and globally, there has been a significant increase over the past few decades in people’s endorsement of individualism as a core value (Santos et al., 2017). Individualism refers to core beliefs, values, or worldviews that “promotes a view of the self as self-directed, autonomous, and separate from others” (Santos et al., 2017, p. 1228). It is possible that a growing emphasis on individualism both at the individual and societal levels plays a role in increasing interest

in self-reliance to examine evidence related to issues of personal, community, or societal importance, rather than interest in relying on individuals with expertise or scientific institutions for advice. Similarly, research points to a positive relationship between prioritizing values around benevolence and concern for others and nature (as opposed to self-preservation and advancement) to pro-environmental behaviors and decision making (Sagiv & Schwartz, 2022; Steg, 2016).

An overall decline in factors associated with social capital, such as good will, empathy, trust among people, trust in civic institutions, and civic orientation, in the United States over generations is a second factor that could play a role in explaining societal trends relevant to misinformation about science (Aldrich & Meyer, 2015; Putnam, 1993, 2000). Virtual spaces created by various internet platform technologies—search, social media, encrypted messaging, etc.—offer the potential, at least, to either undermine or promote social capital through effects on networks, information, and norms (González-Bailón & Lelkes, 2022). While it is clear that virtual communities are different than from traditional communities (Memmi, 2008), the circumstances in which such communities facilitate or undermine social cohesion is less clear (Chambers, 2013; Percy & Murray, 2010; Zhou, 2020). For example, sharing of misinformation on social media may in part be driven by a desire to either maintain or build social capital within a group, although some work finds that strong social ties can also increase the effectiveness of efforts to debunk misinformation (Pasquetto et al., 2022). Others have posited that declining social capital may be linked to more extreme groups that rely more on ideology than on evidence (Lewandowsky et al., 2017).

CHARACTERIZING THE 21ST CENTURY INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM

The nexus between people, societies, and the information they are collectively producing, exposed to, and consuming comprises the information ecosystem that people experience. In fact, this interplay of individual characteristics, social forces, and technological changes means that there is not one shared experience of the information ecosystem. In this networked ecosystem, people can move between their in-person and online networks (Edgerly & Xu, 2024) and can vary dramatically in their access to accurate scientific information and exposure to misinformation. Algorithmic curation and targeting based on demographics and online activity (Brossard & Scheufele, 2022) shape how each person experiences the information ecosystem. Patterns of trust play a role in the sources for scientific information that people seek and believe on- and offline (Green et al., 2023). Moreover, economic forces are reshaping journalism, with a decline in the

resources dedicated to science reporting and local news, in ways that affect all people, but may particularly affect people living outside of major cities (Kim et al., 2020a).

The range of technologies that have comprised our public information environment in the past 100 years reveals various shifts in key dimensions of those technologies that hold important implications for understanding misinformation about science. These include the level of information density or detail made possible by those technologies along with the formats (e.g., written word vs. audio-visual) and timing (e.g., delayed vs. immediate) in which information is transmitted and consumed (e.g., hierarchical vs. participatory). The past century has also witnessed moments of prominence for print media, which largely required audiences to read written content reflecting events occurring a day or a week ago, to the rise of electronic broadcast media, which delivered sounds and images to people in their homes relatively instantaneously via a limited spectrum of available frequencies on public airwaves. The latter half of the 20th century marked a shift to video content delivery via cable—for those households that could afford subscription fees—and more recent years have seen the rise of content distribution via networked computers (i.e., the internet). Structures of the contemporary information ecosystem may contribute to facilitating the dynamics of misinformation about science. Below we discuss some of the most significant structural aspects to consider: audience fragmentation and hybrid media; the emergence of new information technologies and platforms, including artificial intelligence (AI); and context collapse.

Audience Fragmentation and Hybrid Media

More recently, the information ecosystem has expanded and become substantially more complex, fragmented, and hybrid. The large audience share enjoyed by just a few broadcast television networks in the 1970s has fractured, and now many different outlets have emerged to compete for attention. For-profit media organizations continue to aggregate audience exposures over time into mass audiences for the purposes of advertising sales, but nonetheless, even when relatively large numbers of people have engaged content, individual audience members are not always interconnected with one another (Webster & Phalen, 1996). The fragmentation of audiences has not slowed the general spread of some content, per se; in fact, the availability of peer-to-peer diffusion through electronically connected social networks has sped up the pace of information (and misinformation) sharing in the 21st century relative to the 20th century.

Audience fragmentation has occurred alongside and intertwined with the rise of “hybrid media,” where information and misinformation can flow among and between peer-to-peer social networks and mass media outlets.

Indeed, these communications channels are so interconnected at this point that the current information infrastructure in the United States, at least as it is available to many people, can be viewed as a hybrid array of social media platforms, broadcast channels, and media organizations that produce a range of live content and content available for asynchronous engagement by various audience members (Chadwick, 2017). The contemporary information ecosystem is a web of organizations and social networks and individual people operating simultaneously to engage, deliver, and share content with one another; as a result, in recent decades, there have been increased efforts among researchers to consider possibilities for cross-level interactions between interpersonal and mass communication channels (e.g., Altay et al., 2023; Southwell, 2005; Weeks & Southwell, 2010). There is increasing interplay and fluidity between people’s online and offline communication environments (e.g., Hampton et al., 2017). An individual can interact with a friend or colleague in person in one moment and then on social media in the next. Online personal messaging platforms, such as WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger—which people often use to communicate with existing strong-tie networks of friends, family, co-workers, and community members in closed, one-on-one or small group conversations—further blur the lines between online/offline and public/private communication (Chadwick et al., 2023). Information readily flows from more public platforms like news websites or Facebook into private messaging apps, where information sharing is highly personalized, and interpersonal factors like social trust and conflict avoidance shape people’s interactions with information and misinformation (Chadwick et al., 2023; Malhotra & Pearce, 2022; Masip et al., 2021).

In the contemporary ecosystem, information can more easily cross geographic, linguistic, and cultural borders than in the past, through and across global platforms like Facebook, WeChat, WhatsApp, Telegram, Signal, YouTube, and X. In addition, global migration has given rise to diasporic communities that form transnational information networks with unique communication patterns and practices (Nguyễn et al., 2022). For diasporic communities, media—especially digital media—play an important role in building and sustaining relationships in both their home and host countries (Candidatu & Ponzanesi, 2022). Some communities may rely on these sources to fill information voids when information in their native language is unavailable (Asian American Disinformation Table, 2022). Encrypted messaging applications like WhatsApp, Signal, Telegram, and WeChat are particularly popular among immigrant populations in the United States for their ability to support private communications and connect sub-populations that share identities (Trauthig & Woolley, 2023). Other data indicate that some communities rely more heavily than others on some platforms for information. For example, some surveys find that

Latino populations use Facebook, YouTube, and Whatsapp at higher percentages than other populations (Equis Institute, 2022). Finally, the openness of these systems makes them vulnerable to disinformation campaigns (Johnson & Marcellino, 2021).

Emergence of New Information Technologies and Platforms

There have been dramatic shifts in journalism and media production and dissemination over the past two decades that have important implications for the spread and potential impacts of misinformation about science. In the 21st century, the emergence of online platforms—including certain social media applications, large search engines, and websites hosted on the internet (e.g., Abbott, 2007)—has enabled the creation of a large volume of content through an increasing array of creators with limited moderation, increasing personalization of content and online social groups, and the consumption of content outside of its intended contexts (i.e., context collapse—discussed in more detail below; Kümpel, 2020). These features have enabled a qualitative shift in how people consume, interact with, and share information. Rapid advances in artificial intelligence have the potential to further transform the information ecosystem.

Increasing Volume of Content and Limited Moderation

There has been a major increase in the sheer volume of content (Gitlin, 2007), and technological changes have reduced the cost of producing and sharing information, allowing those who previously only consumed information to also become information producers and disseminators (Young & Miller, 2023c). Removing barriers to entry to the digital information space offers both tremendous opportunities to share creative expression, increase access, spread power more equitably, and promote understanding, yet may also incidentally devalue or make it more difficult to discern scientific or medical expertise. This reduction in the “barriers to entry” in the contemporary information ecosystem thus has critical implications for the (intentional and unintentional) production and dissemination of misinformation about science. At the same time, there are also “data voids” where online searches fail to provide results or only return unreliable information that can be exploited by purveyors of disinformation, such as by capitalizing on breaking news, by creating new terms or by co-opting old terms that are not typically used by other content producers (Golebiewski & boyd, 2019). In science, some of these voids may relate to conspiracy theories or rumors that scientists have not directly addressed or debunked.

This abundance of content produced by an increasing array of creators has changed the dynamics of how individuals, communities, and societies

interact with information. Where high-quality information was previously scarce, the internet enables an abundance, leading some to suggest the limiting resource is increasingly people’s attention (Pedersen et al., 2021). At the same time, this new ecosystem also includes large amounts of low-quality or questionable information, including about science. The World Health Organization (WHO) calls this phenomenon an infodemic, where abundant information of variable quality makes it challenging to distinguish between true and false information (Briand et al., 2021; WHO, n.d.). While the term is heavily associated with the recent COVID-19 pandemic, infodemics also manifested during other public health emergencies, including the 1918 influenza pandemic, HIV/AIDS epidemic, and SARS-CoV-1 outbreaks (Tomes & Parry, 2022). Online search is particularly important in helping people sort through the enormous amount of information available online (Brossard & Scheufele, 2013).

Online platforms currently experience limited government regulation, discussed in more detail in Chapter 7, and even broadcast television content is monitored only partially and in a post-hoc fashion for health claim accuracy (Southwell & Thorson, 2015). This lack of (government-led) regulatory oversight in turn holds critical implications for the nature of the information ecosystem that individuals and communities inhabit, as various entities in that system (e.g., privately held companies that host social media platforms) have taken on management and moderation roles to varying extents and for diverse reasons that only sometimes align with the public interest. Moreover, online platforms have shown uneven and often tardy enforcement of their own policies regarding offensive content (The Virality Project, 2022).

Personalization

The abundance of media options now available in the digital environment gives audiences the opportunity to selectively curate and personalize what kinds of information to consume (Prior, 2007). Algorithms also continue to play an important role in shaping the content people consume (Brossard & Scheufele, 2022); however, substantial evidence exists that individuals selectively expose themselves to media sources and content based on their beliefs, interests, and motivations (Feldman et al., 2014, 2018; Muise et al., 2022; Mummolo, 2016; Prior, 2007; Robertson et al., 2023; Stroud, 2008; Wojcieszak, 2021). Moreover, individuals develop different patterns of media use across combinations of media platforms, often referred to as “media repertoires” (Hasebrink & Popp, 2006). These repertoires vary according to the background characteristics of users, such as demographics, socio-economic status, and levels of political engagement (Edgerly et al., 2018; Kim, 2016). Social media platforms have additional features that provide social cues (e.g., likes, follows, and comments) that

can personalize distortions of majority opinions. In other words, people receive information about the preferences of their own homophilic social networks but this can create a false impression of a more widely-held consensus (Lorenz-Spreen et al., 2020). These same features can also reinforce existing opinions or increase extremism.

The evidence related to the role of social media in creating echo chambers is more complex. With the rise of polarization within American society (Druckman & Levy, 2022; Iyengar et al., 2019), there are concerns that media consumers are increasingly siloed in ideological spaces that magnify existing beliefs and messages and provide insulation from opposing views, either accidentally or through purposeful exclusion (Arguedas et al., 2022; Nguyen, 2020). The findings are mixed for the prevalence of such spaces related to politics, with more recent studies finding more evidence of echo chambers (Cinelli et al., 2021; González-Bailón et al., 2023; Nyhan et al., 2023) than older studies (Dubois & Blank, 2018; Guess, 2021; Guess et al., 2018a). However, a recent literature review also found comparatively less evidence for how these insulated groups may form around science topics than exists for understanding how they form around political topics (Arguedas et al., 2022). Another recent review focused on the nature of the information environment related to environmental decision making similarly concluded that most people in the United States access and engage with diverse information, though this may be less true for people who hold more extreme views (Judge et al., 2023). Methodological differences may partly explain the mixed findings; some studies relying on digital trace data find more evidence of their existence than those that rely on self-reported data (Terren & Borge, 2021).

Artificial Intelligence

Technological developments in AI are evolving rapidly. Though much remains to be learned about how AI will shape the information ecosystem, it has increased the public availability of online tools that generate text, audio, images, and video that accurately mimic human activity. For example, large language models (LLMs) such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini (formerly Bard) simulate the experience of chatting textually with a seemingly omniscient interlocutor. In addition, generative AI is proliferating, and many technology companies are integrating their own LLMs into their products, increasingly changing how people search and receive search results across platforms. These tools can also generate authentic-looking scientific papers (Májovský et al., 2023) and scientific visualizations (Kim et al., 2024), and there is increasing evidence of their undeclared use in published papers (Joelving, 2023) and in peer-review (Liang et al., 2024). To this end, scientific publishers have published commentaries on the topic,

specifically regarding AI-generated fraud and how to mitigate its spread (Alvarez et al., 2024; Bergstrom & West, 2023; Jones, 2024).

Indeed, such technological advancements have raised concerns about the role of AI in both proliferating and curtailing misinformation, as several deepfakes—AI-generated images and videos that look real—featuring prominent individuals have gone viral on social media (Ellery, 2023; Metz, 2021). In addition, Meta, the parent company to Facebook, released a large language model (LLM) specifically designed to assist scientists with tasks such as summarizing academic papers, solving math problems, writing scientific code, and annotating molecules and proteins; but this technology only lasted three days because of its inaccuracies (Heaven, 2022; West, 2023). While empirical research on AI tools is limited given the recency of these technologies at the time of this writing, there are concerns about their capacity to generate convincing misinformation (Kreps et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2023), including generating scientific citations that do not exist (Walters & Wilder, 2023). At the same time, these tools have also been hailed for their proficiency at detecting misinformation (Ozbay & Alatas, 2020). Indeed, automated misinformation detection has been a major research goal among more technical researchers of the topic (e.g., Joshi et al., 2023), although this is arguably a form of “solutionism” (Morozov, 2013)—the idea that all societal challenges can be solved with technological solutions—that makes unwarranted assumptions about the objectivity or universal applicability of machine-generated decisions (Byrum & Benjamin, 2022) or assumes that technology can provide the solution to more complex social challenges (Angel & boyd, 2024). Importantly, these new generative information technologies dramatically lower the production cost of information1 and therefore increase the potential for a massive flood of information of all modalities and quality.

Decontextualization and Context Collapse

One consequence of the shifts in information production, distribution, and consumption described above is that people are now increasingly exposed to information that lacks context and nuance. One specific form of this decontextualization is “context collapse”, which refers to when discrete pieces of information as well as larger narratives or stories about some issue or topic intended for one group become visible to a group other than the intended audience (Davis & Jurgenson, 2014; Marwick & boyd, 2011; Pearson, 2021). Such context collapse has implications for the spread, consumption, and potential impacts of misinformation about

___________________

1 Although the production costs are lower for an individual, the environmental costs of generative AI are high (Chien et al., 2023).

science on individuals, communities, and society as a whole. For example, scientists may communicate with one another in a manner that presumes common assumptions (e.g., non-colloquial meanings of widely used terms) and knowledge bases in ways that can mislead non-experts (Somerville & Hassol, 2011); as a result, when communications between scientists that use such words move into the public domain, they may be interpreted by non-scientists in ways that are highly inconsistent with the original intended meanings. For example, a vaccine manufacturer drew an analogy between computer software and mRNA, describing mRNA as “the software of life” (Larson & Broniatowski, 2021); however, the software analogy was not literal. The analogy was made public on a website that did not make this clear and was seen by individuals who may have held different assumptions, including those that attributed malicious intent to vaccine manufacturers. This contributed to the conspiracy that mRNA vaccines can “change your DNA” and can “program” vaccinated individuals in a manner that would ultimately impinge upon their autonomy.

Relatedly, it is also common to consume information without the benefit of meaningful context, and in formats and time periods that differ from the original creation (Brandtzaeg & Lüders, 2018). Segments of original content, including misinformation, can continue to “live” actively online, disappearing for a time only to reappear in people’s feeds long after an initial event or headline has happened. Theoretically, this content can live on indefinitely, although some evidence exists that collective attention on topics of public discussion is getting shorter and shorter (Lorenz-Spreen, et al., 2019). For example, a person’s first encounter with a video clip or a print news story may not occur in the format of original broadcast but rather via peer-sharing on a social media platform or through a mobile phone text message. These variations in how people encounter the same information (or misinformation) matter because different platforms differ in the amount of explanation and context that people encounter. For example, the immediate impact that a video clip about a piece of contested or controversial science might have on an individual may be quite different for someone who sees the video embedded within the original news broadcast (which may provide much more context to inform viewers about the significance of the specific clip) versus for someone who only sees the clip shared with them by a friend on social media (which both removes the broader context and sends a socially relevant signal regarding the importance of that clip).

One set of implications of increasing decontextualization and context collapse relates to the ways in which these phenomena affect what sources of information or knowledge are viewed by various groups as legitimate, authentic, and trustworthy. Unrestricted exposure to several competing narratives, as can frequently happen in our current information ecosystem,

can undermine trust in traditional sources of legitimacy, including scientific discourse (Lyotard, 1984). Lack of context appears to decrease the salience of specific information sources more than does, for example, changes in the simple volume of content. This means that the nature and format of the “encounters” that people have with information (especially via online platforms) may hold consequences for misinformation acceptance more than does the sheer torrent of misinformation available to an audience.

Complex Interactions and Consequences

It is important to note that not all changes in the broader information environment and context of contemporary life necessarily push in the direction of greater generation, dissemination, and/or uptake of misinformation about science. Under some conditions, for example, reduced barriers to entry into the digital information space may lead to better, fairer, and more just use of valid scientific information in collective or societal decision making, while decreasing the impact of misinformation. And as certain institutions lose some of their hold on power (e.g., power to define “correct” knowledge)—including ones with long histories of discrimination against certain groups and the wielding of authority and power to shape cultural and political narratives—others may gain prominence and broader acceptance, with important implications for managing the spread and/or impact of misinformation about science. For example, scientists and decision makers (e.g., natural resource managers, policymakers, and regulators) are increasingly recognizing the importance of Indigenous and traditional (ecological) knowledge, particularly around issues of sustainability and resource management (Whyte et al., 2015). These represent shifts toward valuing “the actions, strategies, resources, and knowledge that Indigenous groups mobilize to navigate environmental change” (Reo et al., 2017, p. 203).

FACTORS SHAPING THE SCIENCE INFORMATION ENVIRONMENT

The ways in which people access, engage with, share, and interpret science information is occurring increasingly online in an information environment that is rapidly transforming. Brossard & Scheufele (2022) argue:

[…] the greatest challenge that scientists must address as a community stems from a fundamental change in how scientific information gets shared, amplified, and received in online environments. With the emergence of virtually unlimited storage space, rapidly growing computational capacity, and increasingly sophisticated artificial intelligence, the societal balance of power for scientific information has shifted away from legacy

media, government agencies, and the scientific community. Now, social media platforms are the central gatekeeper of information and communication about science. (p. 614)

Moreover, existing social divisions in access and attention to the information circulating within the science information environment are both replicated and reinforced. For example, research shows that among U.S. adults, those with higher levels of education and higher family income express more interest in science news (Saks & Tyson, 2022), and people often consume science information based on their existing beliefs and social networks (Feldman et al., 2014; Jang, 2014; Yeo et al., 2015). As science information is increasingly shared on social media platforms, automated algorithms based on users’ personal profiles govern the visibility of this content, determining whether a given user is likely to encounter credible science information or not (Brossard & Scheufele, 2022). This topic is addressed in more detail in Chapter 5.

The Quality of News Production, News Deserts, and Resource Constraints

General news outlets are a chief source of science information among Americans (Funk et al., 2017). There are an increasing number of “news deserts”2 precipitated by two decades of newsroom cutbacks and the closing of local newspapers (Abernathy, 2018). More broadly, media deregulation, beginning in the 1980s and culminating with the passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, consolidated media ownership into an increasingly small number of conglomerates, thereby limiting the diversity of available information outlets and imposing commercial pressures on journalism (McChesney, 2015). These news deserts can be especially pronounced in some communities, particularly in rural areas (Abernathy, 2022).

Although science journalism as a field grew in the mid-20th century and accelerated with the space race (beginning with the launch of Sputnik in 1957), seismic shifts in the media landscape since the start of the 21st century and corresponding budgetary constraints have led many news organizations to eliminate or downsize their science reporting efforts (Guenther, 2019; Russell, 2006). The result is that science news in such outlets is of variable quality. Science reporting is often guided by journalistic values and norms that prioritize public attention over careful consideration of scientific method and evidence (Dunwoody, 2021). Many journalists lack specialized training in science (Dunwoody, 2021), which can make it

___________________

2 “A community, either rural or urban, with limited access to the sort of credible and comprehensive news and information that feeds democracy at the grassroots level” (Abernathy, n.d.).

challenging for them to correctly interpret scientific research and present it in the appropriate context. Science news is also increasingly intersecting with politics (Russell, 2006) or is politicized (Chinn et al., 2020; Hart et al., 2020), a source of frustration for many news consumers (Saks & Tyson, 2022). Moreover, the mediated interactions between journalists, scientists, and the public, as enabled by social media platforms and other digital communication technologies, add to the complexity of the science information environment (Dunwoody, 2021). Increasingly, power resides in control over the flow of information, not its creation (Chadwick, 2017). The diversity and fragmentation of the hybrid media environment has weakened the grip of journalistic and political elites over the flow of information, and has opened the door for a diversity of communicators, including ordinary citizens, to intervene in public discourse in newly expansive ways.

Competing Interests and Public Relations

The science information environment is also increasingly competitive, particularly in the United States’ diverse and decentralized information ecosystem, which has relatively low support for publicly-funded independent media (Neff & Pickard, 2021). This means that voices from the scientific community are increasingly competing with well-resourced entities and actors that vie for control to shape public discourse, including about scientific topics. To that end, organizations—ranging from powerful corporations to smaller advocacy groups—employ public relations firms to conduct “information and influence campaigns” that aim to shift public opinion and political decision making in their favor (Brulle & Werthman, 2021; Manheim, 2011). Although public relations strategies related to science issues are not new, it has become easier for professional communicators in a hybrid media system to manipulate, target, and amplify misinformation about science, especially in a largely unregulated information ecosystem where actors with the most resources have outsized influence on shaping public narratives (Pickard, 2019). In the news industry, boundaries between editorial and advertising are eroding, giving advertisers, which are a key source of financial support for many news outlets, increased influence over the quality of science information available to the public. For example, brand journalism, which includes native advertising and content marketing, is designed to make corporate promotion appear indistinguishable from objective news stories and can be finely targeted to specific audiences (Serazio, 2021). Some scholars have called for new approaches to media governance and business models to provide safeguards against undue influence over news content by advertisers (Napoli, 2019).

Changing Norms and Practices of Science Communication by Scientists

The science information environment is also shaped by the approaches used by scientists to disseminate their research, both to their peers and to the wider public. The open science movement—a broad term that refers to various efforts in recent years to make scientific research and its dissemination more broadly transparent and accessible to all of society—has brought more transparency and greater access to scientific research (Lupia, 2021), giving rise to new ways of disseminating research findings. In recent history, peer-reviewed journals have been the gatekeepers of scientific research. New publishing models are challenging that status quo. For example, preprints—posted by researchers in online open access repositories (e.g., arXiv, bioRxiv, medRxiv, SocArXiv, OSF Preprints, SSRN) before they have been peer-reviewed and accepted for publication by a journal—make new work rapidly available to any audience. Preprints allow scientists to make their research promptly and freely accessible to other scientists, accelerating the dissemination of research relative to the typical peer-review publication process, which can take months or years. Yet findings from preprints, which have not been formally vetted by the scientific community, can prove to be short-lived, flawed, or incorrect. Some preprints never end up published, and if published, the final article may be substantially revised relative to its preprint version as the result of scrutiny by peer-reviewers.

Open science initiatives often encourage (and universities and funders sometimes require) scientists to publish their peer-reviewed research in an open access format, meaning that research articles are made freely available to audiences without subscription charges. This move toward greater accessibility is important and broadly beneficial in many respects, including positive impacts on improving equitable access to scientific knowledge for communities and groups who cannot afford massive subscription fees, and potentially increasing the perception of the trustworthiness of scientists. This practice is more well-established in some disciplines than others.

An unintended byproduct of open access publishing is the growth of so-called predatory scientific journals (Swire-Thompson & Lazer, 2022). Predatory journals publish science entirely for profit and do not subject research to rigorous peer-review, essentially creating a “pay-to-play” model that can become a conduit for misinformation. Authors publish in these journals for a variety of reasons, including inexperience and professional pressures to publish frequently; predatory journals also allow bad actors to spread false scientific claims by providing a veneer of legitimacy conferred through journal publication (Swire-Thompson & Lazer, 2022; West & Bergstrom, 2021). Articles published in predatory journals are widely accessible, including through scholarly databases and search engines, with most lay audiences as well as scientists outside of their disciplines unable to discern their legitimacy (Swire-Thompson & Lazer, 2022). Furthermore,

leading academic search engine algorithms, such as those used by Google Scholar, automatically index content that contains text formatted as academic references, thus facilitating the dissemination of content that has a surface similarity to credible academic sources. For example, several newsletters from the National Vaccine Information Center—a known source of vaccine misinformation (Kalichman et al., 2022)—are indexed on Google Scholar, presumably because they contain references to academic sources.

SUMMARY

Misinformation about science is a phenomenon that exists within and as a part of a broader social, political, and technological context, including the rapidly evolving information ecosystems that people inhabit in 21st century contemporary society. Table 3-1 provides an overview of the factors discussed in this chapter and their implications. This broader context holds significant implications for more fully understanding the origins, flow, spread, and impacts of misinformation about science, as well as the potential for addressing negative impacts on individuals, communities, and society as a whole. Declining trust in institutions and its intersection with partisanship and structural inequities are two salient features of this wider context that shape how people interact with information from science.

Those forces combined with a changing media landscape mean that people experience the information ecosystem quite differently. Particular features of the contemporary information ecosystem, including the fact that online platforms have greatly reduced barriers to accessing and producing information in part because they are under-moderated, are rapidly shifting the types, volume, and nature of science-related information that people encounter over the course of their daily lives. Importantly, it is increasingly difficult for people to discern accurate and credible information from and about science. It is also more possible than ever for people to exist in different, fragmented information ecosystems that online platforms, other media, and interpersonal spaces make possible and readily accessible. While the evidence about the extent to which people exist in echo chambers or filter bubbles is mixed, it is clear that the contemporary information ecosystem makes it more possible than ever for people to be exposed to content—often consumed without important, original context and nuance. Competing and vested interests as well as intentional public relations efforts are often able to capitalize on the affordances of this information ecosystem. In addition, shifts in the norms of science toward open science, news deserts and other challenges in science journalism create additional complexities. In short, understanding the challenges faced related to misinformation about science and how to address them requires understanding the broader system.

TABLE 3-1 Contextual Features and Factors That Influence Misinformation About Science

| Contextual features/factors | Explanation/definition | Implications for misinformation about science | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic factors shaping how people interact with information | Role of science in society | A balance between the credibility and social capital of science to inform decision making and the power of people to make choices in a democratic society | Technological shifts make it more possible for people to disseminate information on an equal footing with science; misinformation can disrupt being able to make informed choices in a democracy |

| Structural Inequalities | Inequalities based on education level, race or ethnicity, primary language, or geography | Societal factors shape the information ecosystems that people experience; they can limit access to high-quality information from science, increase exposure to misinformation; and increase the potential for harm | |

| Trust in institutions | General decline in trust in many institutions, including education, medicine, and the press; political divides in trust in science and media | People seek or encounter information about science from less reliable sources | |

| Features of the information ecosystem | New information technologies and platforms | Social media and other internet-based large platforms emerge in late 20th/early 21st century | Massive changes to production, dissemination, and consumption of information about science, including entry of many new communicators who previously had limited/no access to large audiences |

| Audience fragmentation | Different audiences distributed across different media, channels, outlets | Fewer very broadly shared trusted sources of information about science means different groups can seek out and/or be exposed to very different pieces of (mis)information about science | |

| Hybrid media | Information ecosystem consists of different channels and media types | Science information travels quickly across media types/platforms, sometimes losing or shifting important context that produces misinformation | |

| Contextual features/factors | Explanation/definition | Implications for misinformation about science | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Features of the information ecosystem | Artificial Intelligence | “[T]echnology that enables computers and machines to simulate human learning, comprehension, problem solving, decision making, creativity and autonomy” (Stryker & Kavlakoglu, 2024) | Potential for negative effects include flooding of system with personalized, plausible misinformation about science, as well as for positive effects from its potential to identify and correct misinformation or make correct information from science more easily accessible |

| Factors shaping the science information environment | Quality and quantity of science news production | Decrease in number of dedicated science journalists; areas of the country without local news coverage; decreased funding for science journalism | Decreases in locally contextualized evidence |

| Competing interests and public relations | Increasingly competitive science information environment | More points of entry for bad actors to manipulate, target, and amplify misinformation about science | |

| Open science movements and professional norms | Growth of preprints, availability of data | Potential for negative effects from context collapse with scientific intramural discourse and broader public discourse as well as for positive effects from increasing free access to scientific information | |

SOURCE: Committee generated.

Conclusion 3-1: Though inaccuracy in scientific claims has been a long-standing public concern, recent changes within the information ecosystem have accelerated widespread visibility of such claims. These changes include:

- the emergence of new information and communication technologies that have facilitated access, production, and sharing of science information at greater volume and velocity than before,

- the rise of highly participatory online environments that have made it more difficult to assess scientific expertise and credibility of sources of science information, and

- the decline in the capacity of news media that has likely reduced both the production and quality of science news and information.

Conclusion 3-2: Trust in science has declined in recent years, yet remains relatively high compared to trust in other civic institutions. Although confidence in the scientific community varies significantly by partisan identity, patterns of trust in science across demographic groups also vary as a function of the specific topic, the science organization or scientists being considered, or respective histories and experiences.

This page intentionally left blank.