Developing a Guide for Transporting Freight in Emergencies: Conduct of Research (2024)

Chapter: 2 Literature Review

Chapter 2. Literature Review

Introduction

This chapter contains a review of literature related to the relief of OS and OW limitations on CMVs in emergencies and disasters. The research team performed a literature review using both manual and computerized methods for the literature search. Researchers utilized the Transportation Research Information Service, the National Transportation Library Repository and Open Science Access Portal, the FEMA and FMCSA websites, and other resources like the Texas A&M University Library System discovery service (EBSCOhost) and Google Scholar.

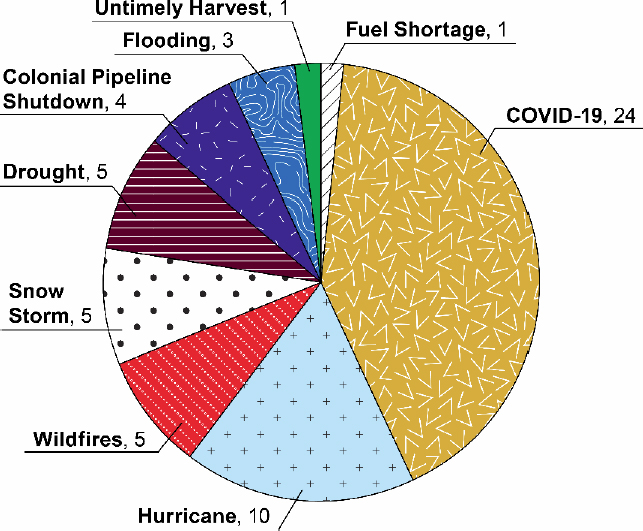

The team did not rely solely on document searches since they lag several months behind current efforts due to their record entry requirements, and they may not include some documents prepared by transportation agencies. In addition to the literature review, and to determine how OS/OW special permitting worked in practice, the project team studied recent emergency declarations posted to the Commercial Vehicle Safety Alliance (CVSA) Emergency Declarations Portal between March 2020 and October 2022.

The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) has documented COVID-19-related overweight limit changes in 44 states and the District of Columbia (AASHTO, 2019). Researchers also reviewed documentation and regulations from various governing authorities regulating OS/OW permitting. Currently, the authorities regulating OS/OW permitting in each state include:

- State DOTs in 41 states.

- Departments of motor vehicles (DMVs) in Connecticut, Maine, Texas, Vermont, and Virginia.

- DPSs in Georgia and South Dakota.

- HPs in North Dakota and Wyoming.

The research team also investigated literature about regulatory relief at the federal, state, and local levels. This also included AASHTO’s OS/OW permit harmonization guide (Athey Creek Consultants, 2022), best practices report, and maximum dimensions and weights of motor vehicles guide (AASHTO, 2019).

This literature review examined FHWA’s information on OS/OW load permits and updated guidance on special permits, in addition to the new permit harmonization updates, agreements, or meeting notes from the following regional state highway transportation official organizations:

- Mid-America Association of State Transportation Officials (MAASTO).

- Western Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (WASHTO).

- Northeast Association of State Transportation Officials (NASTO).

- Southeastern Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (SASHTO).

The Eastern Transportation Coalition project is under consideration and would harmonize the emergency divisible loads (EDLs) for NASTO and SASHTO states.

While many organizations and studies make recommendations about OS/OW permitting, the relief of OS/OW limitations for CMVs in emergencies depends primarily on state and federal laws and regulations. At the federal level, laws and regulations govern when states may issue OS/OW special permits in emergency situations on the interstate highway system. However, states still issue the permits. At the state level, laws and regulations govern when the state may issue special permits for state roads and designate the agency or department of the state government responsible for issuing special permits.

Additionally, both state and federal laws and regulations govern what constitutes an emergency situation and provide the legal authority for the president or governor to declare an emergency and trigger the consideration of special permitting procedures. Thus, the literature review focuses heavily on laws and regulations governing disaster declarations, emergency management and emergency powers, OS/OW limitations and permitting, and documents produced by organizations and groups designed to harmonize state permitting processes related to the relief of size and weight limitations during emergencies or disasters.

The review measured how the system works in practice by examining the CVSA Emergency Declarations Portal for U.S. state declarations related to the size and weight limits of CMVs. Researchers conducted a detailed analysis of federal and state declarations affecting size and weight limits to explore the laws and regulations affecting the relief of OS/OW limits in disasters and emergencies in the United States.

This chapter includes the following:

- A review of laws, regulations, and guidance.

- A literature review on various types of disaster and emergency declarations and overweight special permits.

- A summary of lessons learned about the overweight special permits process during past disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic.

- A review of the different federal, state, and local special permit systems, organizations, and their variances.

- A review of meeting notes from the Emergency Route Working Group.

Primer on Laws and Regulations on the Federal and State Level

Given the heavy reliance on statutes and regulations in this literature review, a brief and general explanation of the structure and implementation of laws and regulations at the federal and state level is necessary. Regulatory authority granted by the legislative branch to the executive branch appears in federal or state codes, while an executive branch department or agency’s rules/regulations appear in federal or state regulations.

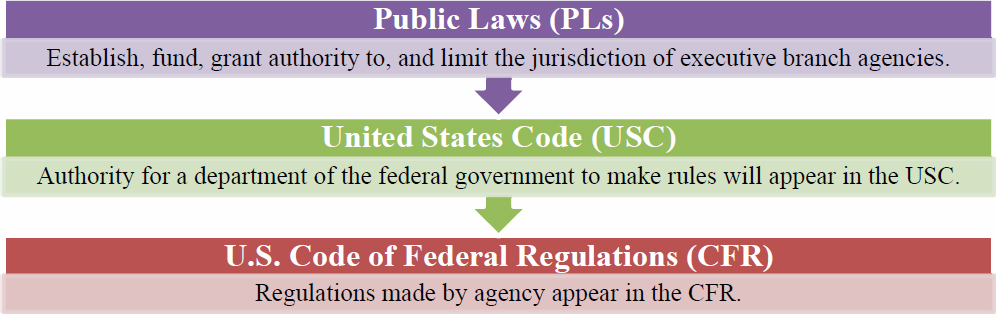

At the federal level, Congress passes acts that, when signed by the president of the United States, become PLs. Public laws establish, fund, grant authority to, and limit the jurisdiction of executive branch agencies. They do this through the creation or amendment of the U.S. Code (USC). Therefore, the authority for a department of the federal government (part of the Executive Branch under the U.S. Constitution) to make rules will appear in the USC, while the regulations made by that agency will appear in the U.S. CFR. Figure 1 shows a brief explanation

and flow of laws, codes, and regulations. Similar systems exist at the state level, though the naming conventions may vary. Administrative codes contain regulations, while statutory codes contain laws (Franklin County Law Library, 2022).

Administrative codes contain regulations, while statutory code contains laws.

Legal documents and this literature review use the words rules and regulations interchangeably. Laws grant authority to make rules/regulations. Rules/regulations have the weight of law under the legal authority a legislature grants. Under its rulemaking authority, the department/agency of the executive branch of the federal or state government implements regulations through an administrative process also defined by federal or state law. For the federal government, this administrative procedure appears in Chapter 5 of Title 5 of the USC (5 USC 500 et seq.). States may adopt a similar standardized rulemaking procedure across their agencies, though with significantly more variation.

Likewise, the legislative branch may enumerate additional powers or limit powers of the executive branch through laws and the U.S. or state code within the confines of the authority granted to the executive and legislative branches under the U.S. or state constitution. In this way, the president or a governor may execute the laws of the United States or their state in an emergency or disaster under laws passed by a legislature or enumerated in their respective state constitutions.

Federal and state departments and agencies may also clarify rules/regulations. These clarifications generally explain how a department or agency will interpret or enforce regulation. Likewise, state attorney generals may also issue clarifications to state law that interpret state law. These interpretations can affect regulation and regulatory authority and enforcement by a state agency or department. Finally, both state and federal courts may rule on lawsuits related to specific laws or regulations that result in the revision or nullification of a law or regulation, or the court may issue a ruling on a law or regulation that provides an interpretation of the law or regulation or its enforcement, thereby limiting or expanding its provisions.

In addition to federal and state-issued regulatory guidance, independent organizations like the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) issue best practices guidance. These independent

documents do not carry the force of law directly. That said, guidance can become part of the law or become binding through contractual means between levels or agencies of government. These means of obtaining compliance with mandates outside of authorities in the USC or state code or constitutional authority often come with financial incentive or penalty to encourage compliance. For example, the federal government obtained state compliance with several federal traffic safety mandates and the legal drinking age by withholding federal highway money from states not in compliance.

States may similarly apply financial measures to obtain compliance at a county, parish, or municipal level. A law or regulation may grant authority to a department or agency to cut or withhold funding for a program unless the government or entity receiving that funding complies with guidance or other mandates. Likewise, many federal and state grant programs include provisions that require applicants to comply with guidelines or other rules if they wish to apply for and receive the grant. An example is the requirement for states to implement the National Incident Management System as defined in FEMA guidance documents if they wish to receive FEMA grant funds.

Finally, a federal or state law or regulation may reference a guidance document, thus making it a standard applicable under the law. The most common example of this in the United States is when local building codes reference NFPA standards or state regulatory authorities’ reference NFPA standards related to the training and operations of first responders.

Defining Emergency and Disaster

Some confusion arises in the freight community when discussing emergency and disaster declarations because such declarations may rely on different elements of law that define emergency and disaster differently. More specifically, relief from overweight restrictions during disaster includes two different elements of federal law, though only one applies broadly to all states.

Specifically, 23 USC 127(h)(i) requires a presidential declaration under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (42 USC 5121 et seq. [“and what follows”]), before states may issue special permits to overweight vehicles for divisible loads. When Public Law 112-141, the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21), added the language for 23 USC 127(h)(i) to the USC, FHWA issued implementation guidance for states. This guidance explicitly stated the three conditions necessary for states to issue special permits under 23 USC 127(h)(i):

- The president has declared an emergency or a major disaster under the Stafford Act.

- The permits are issued in accordance with state law.

- The permits are issued exclusively to vehicles and loads that are delivering relief supplies (Lindley, 2013).

However, the preceding section of the law, 23 USC 127(h)(1) and (2), which applies only to fuel shipments between Augusta and Bangor, Maine, on Interstate 95 for use by the Air National Guard base at Bangor, requires only a “national emergency.” That section refers to emergency powers in the USC under Title 10, as regulated by the National Emergency Act, 50 USC 1601 et

seq., not the Stafford Act, though presumably a Stafford Act declaration affecting that route or otherwise related to emergency shipments of fuel to Bangor would also qualify.

The Disaster Relief Act of 1974 and the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act of 1988 that amended it defines an emergency as:

Any occasion or instance for which, in the determination of the President, federal assistance is needed to supplement State and local efforts and capabilities to save lives and to protect property and public health and safety, or to lessen or avert the threat of a catastrophe in any part of the United States (Congressional Research Service [CRS], 2013).

That definition is the one that applies to Stafford Act declarations. There is a separate and different definition related to the FMCSR that regulates topics like CMV hours of operation. This emergency definition, contained at 49 CFR 390.5, states:

Emergency means any hurricane, tornado, storm (e.g., thunderstorm, snowstorm, ice storm, blizzard, sandstorm, etc.), high water, wind-driven water, tidal wave, tsunami, earthquake, volcanic eruption, mud slide, drought, forest fire, explosion, blackout, or another occurrence, natural or man-made, which interrupts the delivery of essential services (such as electricity, medical care, sewer, water, telecommunications, and telecommunication transmissions) or essential supplies (such as food and fuel) or otherwise immediately threatens human life or public welfare, provided such hurricane, tornado, or other event results in:

- A declaration of an emergency by the President of the United States, the Governor of a State, or their authorized representatives having authority to declare emergencies; by FMCSA; or by other Federal, State, or local government officials having authority to declare emergencies; or

- A request by a police officer for tow trucks to move wrecked or disabled motor vehicles.

Further, 49 CFR 390.5 defines several other emergency conditions and emergency relief:

Emergency condition requiring immediate response means any condition that, if left unattended, is reasonably likely to result in immediate serious bodily harm, death, or substantial damage to property. In the case of transportation of propane winter heating fuel, such conditions shall include (but are not limited to) the detection of gas odor, the activation of carbon monoxide alarms, the detection of carbon monoxide poisoning, and any real or suspected damage to a propane gas system following a severe storm or flooding. An “emergency condition requiring immediate response” does not include requests to refill empty gas tanks. In the case of a pipeline emergency, such conditions include (but are not limited to) indication of an abnormal pressure event, leak, release, or rupture.

Emergency relief means an operation in which a motor carrier or driver of a CMV is providing direct assistance to supplement State and local efforts and capabilities to save lives or property or to protect public health and safety because of an emergency as defined in this section.

It is important to note that only presidential declared disasters under Stafford Act authority enable states to issue special permits. Other federal emergency declarations do not enable the states to issue OS/OW special permits, except for fuel deliveries to the Air National Guard base in Bangor, Maine.

Confusion arises in the freight community when discussing emergency and disaster declarations because such declarations may rely on different elements of law, which define emergency and disaster differently. More specifically, relief from overweight restrictions during disaster includes two different elements of federal law, though only one applies broadly to all states.

The definitions of emergency above apply to exemptions and waivers to the FMCSR in emergency conditions (see further discussion below). State and federal emergency declarations affecting OS/OW vehicle permits may refer to both the special permitting process under 23 USC 127(h)(i) and the FMCSR waivers.

However, Stafford Act declarations are not the only kind of emergency power available to the president or states. The president can also declare national emergencies under authority granted in at least 137 distinct parts of the USC, including the Insurrection Act, in accordance with the National Emergency Act of 1976, codified at 50 USC 1601 to 50 USC 1651 (Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, 2019).

Historically, presidents have generally declared national emergencies via executive order or proclamation. Federal statutes do not define the meaning of national emergency, allowing for broad interpretation by the president (who has determinative authority under the Stafford Act as well). Further discussion of this topic appears in the sections below.

Additionally, some emergency powers exist within the executive branch of state and federal governments that fall to members of the Cabinet (at the federal level) or leadership in executive branch agencies, or the heads of state agencies (some of whom are elected, depending on the state). For example, the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) can declare a public health emergency under Section 319 of the Public Health Service Act. Likewise, some emergency authorities exist within state health departments and state DOTs, among other agencies.

At the state level, the declaration of a state emergency or disaster is equally varied. States codified elements of the Stafford Act to qualify for federal assistance in disasters, thus establishing a state system of disaster declaration. Governors and state legislatures also possess widely divergent emergency powers under both their state’s constitution and statutes. The form and limits of these powers vary from state to state.

Further, some states grant broad emergency authority to governors with little or no legislative oversight. Therefore, the state powers available to some governors may be broader than those available to the president at the federal level, especially concerning the imposition of martial law and the use of military forces (discussed further below).

Likewise, disaster and emergency declarations can overlap and relate to one another. For example, following a hurricane, a state may (a) request a federal disaster declaration under the Stafford Act; (b) issue a declaration waiving part of the FMCSR for drivers delivering emergency relief supplies while also establishing special permits for overweight divisible loads under 23 USC 127; (c) declare a state emergency under state law and deploy the National Guard to prevent looting in damaged areas; and (d) request that federal troops assist with restoring order in those areas under elements of the Insurrection Act.

Likewise, as the COVID-19 pandemic showed, the same event/incident can have a public health emergency, presidential and state disaster declarations, and both state and federal emergency powers invoked. In each case, the authority cited for the declaration, the powers invoked, and the role played by federal and state agencies will vary.

The form and limits of emergency powers vary from state to state. Governors possess divergent emergency powers as defined by their state’s constitution and statutes. In some states, the state legislature or another government official may hold emergency powers exercised by a governor in another state.

Disaster Declarations

Disaster declarations are the system by which local communities, counties/parishes, states, and the federal government respond to disasters, both natural and man-made. Since 1988, this system of disaster declaration has operated at the federal level under the Stafford Act.

Because of its frequency of use, Stafford Act declarations and disaster authority are well established and practiced across the United States, and presidential declarations have occurred under every presidential administration since its inception. This system of disaster declaration is the one most associated with natural disasters in the United States, even though its authority extends to other areas.

Stafford Disaster Declarations

The Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (Public Law 100-707), signed into law on November 23, 1988, established the present statutory authority for federal disaster responses. Each state within the United States has implemented some aspect of the federal law into state law, thus creating a system across states of requesting a declaration between county or parish and the governor, similar to the system the Stafford Act implemented between governors and the president. At the federal level, disaster response generally falls under the authority and responsibility of FEMA, part of the Department of Homeland Security since its creation in 2002.

When the state requests a federal disaster declaration through FEMA, the president can then declare a federal disaster. In a known, impending disaster (e.g., a hurricane), a state can

preemptively declare an emergency/disaster and apply for federal assistance. In addition to aid from federal agencies to a state or local government, a disaster or emergency declaration allows for reimbursement of some state and local expenditures in responding to the disaster through programs administered by FEMA. In significant disasters, Congress may authorize additional funding and create special relief programs, as it did after Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy or during the COVID-19 pandemic.

State, County/Parish, and Local Disaster Declarations

Although the system varies in each state, in the event of a disaster that overwhelms a local community or county’s ability to respond with local response assets or those provided through mutual aid, a municipal or county/parish executive (mayor or county official) may request aid from the governor, who can declare a county or state disaster. Under provisions of the Stafford Act, governors can then make a request from the federal government for assistance if the disaster exceeds the ability of the state to respond. Not all emergencies or disasters rise to the level of presidential declarations. Some localized incidents may rise only to a state level. While these incidents do not meet the requirements necessary for the special permitting of OS/OW vehicles under federal statutes, they may meet the requirements for FMCSR relief in some cases (see discussion below).

Not all emergencies or disasters rise to the level of presidential declarations. Some localized emergencies or disasters may only require state-level declarations. These may be eligible for FMCSR relief in some cases, though not for special permitting for OS/OW vehicles on interstate highways under federal statutes, which always requires a presidential declaration.

Emergency Declarations

As previously noted, some national emergency declarations (that are not Stafford Act declarations) may only create the federal authority to authorize overweight fuel shipments on I-95 between Augusta and Bangor, Maine, at the determination of the Secretary of Transportation and the Secretary of Defense. However, during the preparation of this literature review, the panel asked questions regarding civil disturbances and other emergency powers.

Likewise, the research team’s examination of emergency declarations for OS/OW vehicles posted to the CVSA website found other authorities, both federal and state, cited by states. In response to the questions raised by the panel, this section explores some of those other forms of emergency declaration and the CVSA declarations outside of Stafford Act declarations, with the important note that these emergencies do not apply to any special permitting process for the interstate highway system under 23 USC 127(i), which requires a Stafford Act declaration.

Federal Emergencies

At both the federal and state level, emergency powers vary widely from powers associated with the Stafford Act and the state systems of the disaster declaration. Emergency powers fall under different laws at the federal and state level depending on the nature of the emergency. Further, some emergency powers, like those associated with public health emergencies, may be the purview of department secretaries or agency administrators within the executive branch of the federal or state government rather than the chief executive.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Section 319 Public Health Emergency authority appeared in several declarations on the CVSA website. An examination found those declarations also (correctly) cited Stafford Act declarations. However, several state-only declarations excluded interstate and national defense highways, relying solely on state statutes and powers for OS/OW special permitting on state and local roads.

Section 319 Public Health Emergencies

Section 319 of the Public Health Service Act (PL 115-96, as amended) authorizes the HHS secretary to declare a public health emergency if a disease, disorder, or bioterrorist attack poses a threat to public health. This action does not require a request from a state, unlike Stafford Act declarations. A Section 319 declaration authorizes the secretary of HHS to provide grants, enter contracts, and conduct and support investigations into causes, treatments, and preventive measures against the disease, disorder, or bioterrorist attack. The secretary can also grant extensions or waive sanctions relating to the submission of data or reports to HHS required under statute or regulation. The secretary may also access funds appropriated to the Public Health Emergency Fund (if Congress appropriates money to the fund) (HHS, 2019).

National Emergency Act Emergencies

The National Emergencies Act (NEA) of 1976 (PL 94-412, 50 USC 1601 et seq.) grants authority to the president to declare national emergencies subject to congressional review. The NEA focused primarily on terminating emergency declarations and powers. Senate Report 93-549, Report of the Special Committee on the Termination of National Emergency, examined the 40-year national emergency originally declared by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1933 under the Trading with the Enemy Act (1917) that Roosevelt used to block gold and silver transactions as an economic response to the Great Depression. Subsequently, the NEA rescinded presidential powers granted under previously declared, but never terminated, emergencies and established a means for congressional review and termination of all future declared national emergencies.

The authority for declaring national emergencies comes from a broad swath of law, much of it economic related or under presidential authority as commander-in-chief of the U.S. Armed Forces under Title 10 of the USC. Presidents declaring national emergencies do so under a power granted them by Congress in the USC, which they cite when declaring the emergency in an executive order or presidential proclamation, which is transmitted to Congress and published in the Federal Register in accordance with the provisions of 50 USC 1621. One study identified 137 instances of the USC granting emergency powers. Since 1976, most of these emergency powers have fallen under the broader constraints of the NEA.

Thus, all such emergency declarations, no matter the law cited to authorize them, become subject to the provisions of the NEA under 50 USC 1622. This section of the act defines the circumstances under which such declarations terminate and establishes a recurring six-month review period for Congress, at which time both houses of Congress must consider a vote on a joint resolution to terminate the emergency.

Despite 50 USC 1622 reviews, some national emergencies continue for many years. For example, a national emergency declared by the Carter administration in 1979 applying sanctions on the Iranian government remains in effect. This emergency, the first declared following the passage of the NEA in 1976, is entering its 44th year, an ironic circumstance given that the

original impetus for the NEA focused on terminating Roosevelt’s depression-era national emergency declaration, then 43 years old. Most economic sanctions that the United States has on other countries fall under the authority of the NEA and make up the bulk of such emergency declarations. However, NEA authority also covers some public health events, like the national emergencies declared for the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2009 H1N1 Influenza pandemic (Executive Office of the President, 2009, 2022). Further, NEA authority can apply to military and security situations, such as the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, or the most recent NEA declaration of April 21, 2022, that prohibited most Russian-affiliated vessels from entering U.S. ports because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine (White House, 2022).

NEA emergency declarations usually have bipartisan support in Congress, and most declarations related to economic sanctions over the last 20-plus years remain in effect. Only one national emergency declaration by a president since the passage of the NEA engendered significant congressional pushback immediately after its declaration (Proclamation 9844—Declaring a National Emergency Concerning the Southern Border of the United States, February 15, 2019). However, Congress did not pass a veto-proof majority resolution terminating the declaration. Instead, President Joe Biden terminated this emergency declaration within weeks of his inauguration. Unlike other national emergency declarations, this proclamation used construction authority under 10 USC 2808, which authorizes military spending for construction projects during a declared war or national emergency. Using the emergency declaration and this authority, the president then appropriated money for a project for which Congress had not passed appropriations. This action represented a new and unusual use of the NEA and led to some discussion of modifying the NEA, as yet unrealized.

Civil Disturbances, Posse Comitatus, and the Insurrection Act

Based on questions from the panel regarding civil disturbances, an explanation of federal emergency powers relating to civil disturbances and the Insurrection Act follows.

Because of limitations on the use of military forces to carry out law enforcement in the United States (defined in the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, PL 45-264, and 18 USC 1385), presidents have limited powers to employ U.S. military forces in response to civil disturbances. The original impetus for the Posse Comitatus Act came from southern states during the post-Civil War Reconstruction era. At that time, the U.S. Army exercised police powers in the former Confederacy. Following the end of Reconstruction and the restoration of statehood, the former Confederate states’ representatives in Congress led an effort to restrict future uses of military forces for such purposes. Consequently, civil disturbances resulting in an emergency generally fall to state authority (discussed further below).

Specifically, 18 USC 1385 states, “Whoever, except in cases and under the circumstances expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress, willfully uses any part of the Army, the Navy, the Marine Corps, the Air Force, or the Space Force as a posse comitatus or otherwise to execute the laws shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 2 years, or both.” Under U.S. law, a posse comitatus is a group of people mobilized or deputized by a sheriff to enforce the law, and it is where the “old west” idea of a posse originates. Essentially, the act

limits the use of the military for law enforcement except when “authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress,” under penalty of fine or imprisonment.

However, 18 USC 1385 does not prohibit military intervention under the Insurrection Act (10 USC Section 251 et seq.) because the Insurrection Act authorizes military force by “Act of Congress.” The Insurrection Act is one of the oldest laws in the United States and one of its more controversial. The origins of the act date to 1792’s Calling Forth Act. Invoked 30 times in the 230 years since its passage, the repeated use of the Insurrection Act against striking workers contributed to controversy surrounding the law. Further, in 1932, the Army acted against civilians without authorization to do so during the Washington, D.C., Bonus Army incident under the Hoover administration. Douglas MacArthur ignored the orders of the president to provide Army support to the police in Washington, D.C., and, in some interpretations, instead acted as though the president had invoked the Insurrection Act, which he had not. The Bonus Army incident raised several concerns regarding the Insurrection Act and represented a violation of the Posse Comitatus Act, which was never addressed or resolved, though it became the subject of debate since (Allen & Dickson, 2004).

Because of limitations on the use of military forces to carry out law enforcement in the United States (defined in the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, PL 45-264, and 18 USC 1385), presidents have limited powers to employ U.S. military forces in response to civil disturbances.

The most used portion of the Insurrection Act is Section 251, which authorizes the deployment of active military forces if the state legislature (or governor, if the legislature is unavailable) requests federal aid to suppress an insurrection (Nunn, 2022). The last use of Section 251 of the law was in response to the Los Angeles riots in 1992 (Nunn & Goitein, 2022).

Sections 252 and 253 of the Insurrection Act allow the president to deploy the military without a request from the state, even against a state’s express wishes. Section 252 authorizes the president to deploy military forces to enforce federal law or suppress rebellion whenever “unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion” make ordinary enforcement of federal law “impracticable” by the “ordinary course of judicial proceedings” (Nunn, 2022).

Section 253 authorizes military intervention in a state under two circumstances. The first authorizes the president to deploy military forces to a state to suppress “any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy that so hinders the execution of the laws that any portion of the state’s inhabitants are deprived of a constitutional right, and state authorities are unable or unwilling to protect that right” (Nunn, 2022). The last time presidents used this portion of the act was in the 1950s and 1960s to enforce the desegregation of schools following Brown v. Board of Education and the passage of civil rights laws, ending Jim Crow era segregation. No president has invoked this section of the act since Lyndon B. Johnson federalized the Alabama National Guard (Nunn & Goitein, 2022).

The second part of Section 253 authority, and the most controversial, allows the deployment of federal troops to suppress “any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy” when it “opposes or obstructs the execution of the laws of the United States or impedes the course of justice under those laws” (Nunn, 2022). As legal scholars note, this section

is very broad and could theoretically apply to the use of military force against any two people conspiring to break federal law.

Further, the Insurrection Act fails to define the terms it uses to authorize the use of military forces. Subsequently, two Supreme Court cases applied interpretations of the act: first, Martin v. Mott (1827) declared the definition of the terms and the conditions under which the law applies, as written by Congress, are exclusively up to the president, and second, Sterling v. Constantin (1932), while not limiting presidential power to invoke the act, did limit the actions military forces may conduct under its authority, reserving jurisdiction to federal courts to review the lawfulness of any action military forces take under the act’s provisions (Nunn, 2022).

Thus, while the federal government may conduct actions against the residents of a state under the Insurrection Act, it cannot violate their constitutional or other legal rights. Prior to Sterling v. Constantin, opponents argued at the time, and historians and legal scholars still argue, that some invocations of the Insurrection Act did violate constitutional rights. In particular, the involvement of the U.S. Army under General MacArthur in clearing out the encampment of the Bonus Army in Washington, D.C., in 1932, which did not invoke the act, raised several issues related to the use of the military against U.S. citizens that related to the Insurrection Act and Posse Comitatus Act (Allen & Dickson, 2004).

Likewise, no federal statute grants authority to the federal government to declare martial law, wherein military forces seize control of and administer a local or state government, though some legal scholars’ interpretations suggest that the Supreme Court implied such powers exist (Lau & Nunn, 2020). States have the power to declare martial law if authorized by the state constitution or state statute. Most states have some measure of executive or legislative emergency power authorizing such actions. For further discussion, see State Emergencies below.

Additionally, federal security and law enforcement may conduct law enforcement actions during civil disturbances in a state when such disturbances threaten or occur on federal property where those federal agencies have jurisdiction. It was under this authority that President Trump deployed federal law enforcement to several states during the George Floyd and Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020 [Executive Order (EO) 13933, June 22, 2020; 40 USC 1315]. Under this legal authority, such forces protect federal property or personnel—for example, a federal courthouse or federal building. Although these forces may or may not coordinate their actions with state or local law enforcement in relation to a broader civil disturbance, they do not generally have jurisdiction outside of federal concerns. This aspect of the 2020 deployments remains a point of contention politically and in some of the states and cities where these federal forces and tactical teams deployed, especially because some of the deployed personnel operated outside of their normal law enforcement and protective functions; for example, Customs and Border Protection agents were deployed to Seattle to protect federal buildings (Brunner, 2020).

State and federal law enforcement may also cooperate or work together when a civil disturbance includes criminal activity that falls under federal jurisdiction, like terrorism, kidnapping, or the use of weapons of mass destruction as defined under federal law. Under federal laws, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) maintains exclusive jurisdiction over kidnapping, acts of terrorism, and the creation, possession, or use of weapons of mass destruction, though they may work

through and with local law enforcement. The FBI may also coordinate and work with the military, the Department of Homeland Security and its subsidiary agencies, and U.S. or foreign intelligence services, especially in cases involving weapons of mass destruction or when the perpetrators include foreign nationals. Likewise, even though the FBI retains jurisdiction it may work with other federal agencies like the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives or the Drug Enforcement Agency. In all such cases, the authority for federal law enforcement is the enforcement of federal law under their existing and normal course of duty.

When federal military forces deploy or move within the United States, under most circumstances, the law requires them to coordinate with the state and authorities. This process is discussed further in subsequent sections. Generally, coordinated military movements include convoy movements or other movements of military vehicles or equipment that the Department of Defense (DoD) or a state’s National Guard coordinates with state DOTs and emergency management officials. Given the sensitivity or classified nature of some of these movements, such coordination may involve a limited number of officials at the state level previously granted clearances by the federal government.

In a disaster or an emergency, federal military forces fall under state and local authority, act under the direction and in support of elected state and local authorities. As previously noted, federal forces cannot conduct activities related to civilian law enforcement. This structure of civilian control means that federal military forces do not have the power of arrest, nor can they conduct actions related to law enforcement against civilians in the United States except in certain proscribed circumstances related to the Insurrection Act and federal civil rights laws, as previously discussed.

However, military police do have law enforcement powers when dealing with other military members. Therefore, an active-duty (under Title 10 of the USC) military police officer may conduct law enforcement within the confines of a federal military reservation under the Uniform Code of Military Justice. Similarly, many federal agencies, including the DoD, have civilian law enforcement operations as part of the security presence for their buildings and personnel. These forces’ jurisdiction is, in most cases, limited to federal property. Federal law enforcement agencies like the FBI, Drug Enforcement Agency, and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives have police powers granted to them under the USC to enforce specific federal laws or regulations. Likewise, some federal investigators, like those in the Environmental Protection Agency, may also have arrest and other law enforcement powers related to their authority under federal law.

Regarding the movement of military forces and their freight, the DoD and state National Guard units follow U.S. and state DOT and FHWA regulations. Within the emergency powers of the president and the DoD, authority exists to waive many regulatory requirements during national emergency or time of war. However, the president and Congress rarely invoke these powers. Further, DoD regulations strictly regulate military roadway movements within the United States on public roads and require compliance with state and federal laws and regulations (U.S. Department of Defense, 2020).

Department of Defense regulations strictly regulate military roadway movements within the United States on public roads and require compliance with state and federal laws and regulations.

State Emergencies

Under state laws and state constitutional authorities, governors and legislatures possess the authority to declare state emergencies. This power may exclusively fall to the governor, the state legislature, or some combination thereof, depending on the state constitution and statutes. Six states (Alabama, Missouri, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and West Virginia) authorize the legislature to declare an emergency, in addition to the governor (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2022).

Most states have some legislative checks on the governor’s emergency powers. Only a few states lack legislative checks on executive emergency powers. Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New Jersey, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Wyoming do not presently include in their statutes legislative oversight of executive emergency powers (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2022).

Due to the widespread use of emergency powers and controversies surrounding their use during the COVID-19 pandemic, many states and U.S. territories reexamined and amended executive emergency powers, a process that continues as of the writing of this literature review. Ten out of 28 states passed legislation limiting executive emergency power in 2020, and 23 out of 47 states and two territories enacted or adopted legislative limits on executive emergency power in 2021, with more than 300 bills or resolutions introduced that year. Five states enacted legislative limits on executive emergency powers in 2022, and 36 states and Puerto Rico also considered such laws (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2022).

Further, U.S. citizens maintain their constitutional and civil rights, including that of habeas corpus, under states of emergency or martial law, and Supreme Court decisions maintain the right of citizens to petition federal courts for injunctive relief if a state declares martial law (Sterling v. Constantin, 1932). Although common in the 19th and early 20th century, especially in the 1930s, the last time a state-declared martial law was in 1963 in Cambridge, Maryland, due to disorder surrounding desegregation. The last time the federal government declared martial law was in 1941 in Hawaii following the Pearl Harbor attack, and military rule lasted there until 1944. While the federal government generally lacks authority to declare martial law in states, Hawaii’s territorial status at the time and wartime conditions following the attack on Pearl Harbor made room for such a declaration.

State emergency declarations fall under a broad scope of emergencies, from public health emergencies to civil disturbances. Unlike federal executive authority, limited by Posse Comitatus and other statutes, governors can deploy state military forces in response to emergencies and civil disturbances and authorize them to conduct law enforcement activities. In most cases, this involves deployment of the state’s National Guard, operating under the governor’s orders and at state expense rather than the federal funding that National Guard forces receive for training under Title 32 of the USC or the Title 10 funds provided to active-duty forces and to federalized National Guard units activated and deployed by the DoD.

At the federal level, National Guard units operate under the regulations of Title 32 USC when under the control of the governor and under Title 10 USC when federalized. The National Guard Bureau, which does not have command authority over state national guards, manages federal funding and standards related to training and preparedness under Title 32. State law outlines the use and pay of state military forces during state-ordered deployments and emergencies. The use of a governor’s state command authority is the means through which the Texas governor currently maintains Texas National Guard troops on state active duty near the Texas border with Mexico, a mission funded by the state and under state authority.

Twenty-two states and Puerto Rico also maintain state defense forces of volunteers not eligible for federal service and not part of the U.S. military. States deploy these volunteers in an emergency or disaster. Although many states deactivated such units in the 1980s and 1990s, the more recent trend is toward more specialized and better-trained state guard organizations capable of emergency management and response roles. For example, both Maryland and Texas maintain units of professional medical personnel that volunteer to serve in support of public health or other emergencies where medical assistance is required. Maryland reorganized its state defense force in 2017, closely aligning it with supporting and assisting the state National Guard and its missions, supporting the Maryland Emergency Management Agency, and creating a new cyber security unit to assist state and local agencies with cyber security (State of Maryland, n.d.). Texas established the Texas Medical Reserve Corps in 2003 in response to the attacks of September 11, 2001 (Texas State Guard, n.d.).

The laws governing state authority for both public health emergencies and other emergencies, like civil disturbances, vary widely from state to state and do not align with federal authorities in the same way the system of disaster declarations under the Stafford Act tends to align at the state and federal level. Further, because of controversies that arose over emergency powers during the COVID-19 pandemic, many states continue to reevaluate these powers and authorities, with the law and regulations affecting public health emergencies still in a state of flux.

State Disaster and Emergency Authority Under 23 USC 127(h)(i) and 49 CFR 390.23

Appendix A contains a summary of state disaster and emergency authorities.

Overweight and Oversize Regulations

Although the federal government establishes regulations affecting vehicles on the Interstate and Defense Highway System, it does not issue permits for OS/OW vehicles on those federally regulated highways. States exclusively issue OS/OW permits. Further, most enforcement of federal and state OS/OW CMV laws and regulations falls to state or local law enforcement, though the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) sets the standards for training CMV inspectors and the regulations they follow in their inspections.

Federal Jurisdiction and Authority

The federal government issues guidance to the states regarding the regulation of weight and size limits for vehicles and regulates trucks engaged in interstate commerce. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 created the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways (also called the Dwight D. Eisenhower System of Interstate and Defense Highways in law). Title 23

USC-Highways, as amended over the years, includes the Federal-Aid Highway Act and subsequent PLs related to the Interstate and Defense Highway System.

Congress granted regulatory authority to the Secretary of Transportation at 23 USC 315 to “prescribe and promulgate all needful rules and regulations for the carrying out of the provisions of [Title 23 of the USC].” This regulatory authority largely falls to USDOT’s FHWA, while other authority is granted to FMCSA and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA).

While the federal government establishes regulations affecting vehicles on the interstate and defense highway system, it does not issue permits for OS/OW vehicles on those federally regulated highways. States exclusively issue OS/OW permits.

Federal Highway Administration

Title 49–Transportation of the USC establishes USDOT and other government agencies related to transportation. 49 USC 104 grants authority to FHWA to carry out the duties and powers vested in the Secretary of Transportation under 32 USC Chapter 4. FHWA provides guidance and regulation related to the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways.

FHWA regulations related to truck size and weight, route designations, and length, width, and weight limitations appear in 23 CFR Part 658, while certification of size and weight enforcement appears in 23 CFR Part 657.

Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration

The Motor Carrier Safety Improvement Act of 1999, codified in 49 USC 113 et seq., established and granted regulatory authority to FMCSA to carry out the duties and powers vested in the Secretary of Transportation related to motor carriers or motor carrier safety except as otherwise delegated by the secretary to any agency of USDOT other than FHWA, and to carry out additional duties and powers prescribed by the Secretary of Transportation. Under this authority, FMCSA must consult with FHWA and NHTSA on matters related to highway and motor carrier safety.

FMCSA, part of FHWA until 2000, establishes standards for the testing and licensing of CMV drivers, collects and disseminates data on motor carrier safety, uses the data to improve safety performance and remove high-risk carriers from the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, and provides financing to states for roadside CMV inspections and other CMV safety programs, through which it obtains state regulatory alignment with federal regulations and guidance. FMCSA also regulates the transportation of hazardous materials and supports the development of unified motor carrier safety requirements and procedures in North America, both across states within the United States and between the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

Regarding OS/OW special permits, declarations establishing special permitting during a disaster or emergency may also waive FMCSA regulations related to hours of service and other components of the FMCSR. A more thorough examination of this aspect appears under the Waivers and Special Permits section below.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

Congress establishes and grants regulatory authority to NHTSA in 49 USC Chapter V. NHTSA regulates vehicle performance standards and partners with state and local government to collect data and create measures to reduce deaths, injuries, and economic losses from motor vehicle crashes (NHTSA, n.d.). These measures include studies of crashes involving CMVs.

Federal Weight and Size Limitation Regulations

Federal Weight Limits

23 USC 127 established maximum weights for the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways. However, other roads within a state fall under state jurisdiction. Congress required the transportation secretary to withhold 50 percent of highway funding apportioned to a state in any fiscal year in which “the State does not permit the use of the Dwight D. Eisenhower System of Interstate and Defense Highways within its boundaries by vehicles with a weight of twenty thousand pounds carried on any one axle, including enforcement tolerances, or with a tandem axle weight of thirty-four thousand pounds, including enforcement tolerances, or a gross weight of at least eighty thousand pounds for vehicle combinations of five axles or more.”

Subsequent articles in this section of the code exempt certain specific highway segments in a small number of states from the provisions of the code without explanation as to the reasons for such exemptions. Some of these are grandfathered rights, or they relate to a route-specific commodity involving weights or sizes of loads that otherwise exceed the provisions of the code or regulation.

FHWA further defined these weight limits in regulation under the authority of 23 USC 315 at 29 CFR Part 658.17. It is important to note that 29 CFR 658.17 limits apply only to the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways and “reasonable access thereto.” However, as noted above, a state that does not apply the weight and size limits defined in 23 USC 127 could potentially lose up to 50 percent of its highway funding at the discretion of the Secretary of Transportation. Consequently, states adopted these rules in state law, with variations applying state-level limitations and regulations on weight and size.

However, several states received special clauses in the relevant statute and regulations that exempted them from some provisions. These are typically grandfathered exemptions that apply statewide, or they relate to a commodity that moves on vehicles or on specific routes that otherwise exceed the provisions of the code or regulation (23 CFR 657-658, 2007; 77 FR 105, 2012).

Divisible and Non-divisible Loads

Title 23 of the CFR defines a non-divisible load in 23 CFR 658.5 as follows:

- As used in this part, non-divisible means any load or vehicle exceeding applicable length or weight limits which, if separated into smaller loads or vehicles, would:

- Compromise the intended use of the vehicle, i.e., make it unable to perform the function for which it was intended;

- Destroy the value of the load or vehicle, i.e., make it unusable for its intended purpose; or

- Require more than 8 work hours to dismantle using appropriate equipment. The applicant for a non-divisible load permit has the burden of proof as to the number of work hours required to dismantle the load.

- A State may treat as non-divisible loads or vehicles: emergency response vehicles, including those loaded with salt, sand, chemicals or a combination thereof, with or without a plow or blade attached in front, and being used for the purpose of spreading the material on highways that are or may become slick or icy; casks designed for the transport of spent nuclear materials; and military vehicles transporting marked military equipment or materiel.

Divisible loads are loads not meeting the above definition. States can issue special divisible load overweight permits under 23 USC 127 authority if the situation meets the following three conditions:

- The U.S. president issues a Stafford Act declaration for the emergency/disaster.

- The state issues the special permits according to state law.

- The state issues the special permits exclusively to vehicles and loads delivering relief supplies (U.S. Department of Transportation, 2020).

Under 23 USC 127, any OS/OW special permit issued by a state expires no later than 120 days after the date of the presidential disaster declaration unless the president issues an extension, as occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. In those cases, states issued their own extensions, citing the presidential extension.

Example of non-divisible loads include wind turbines or cranes. The carrier bears the burden of proof on the more than 8 work hours required to dismantle the load.

Examples of divisible loads include medical supplies, building materials, food and drink, paper products, food supply chain (including livestock), and debris.

Federal Size Limits

Congress set truck size limitations on the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways. Length limitations are defined and limited in 49 USC 31111, and 49 USC 31112 defines property-carrying unit limitations. Width limitations are defined and limited in 49 USC 31113.

FHWA issues size regulations under 23 CFR Part 658. FHWA also provides a pamphlet titled Federal Size Regulations for Commercial Motor Vehicles that illustrates the regulations found in 23 CFR Part 658, which implements the statutes in 49 USC 31111, 31112, 31113, and 31114 (U.S. Department of Transportation, FHWA, 2004).

Like the statutes and regulations regarding weight limits, some states received special clauses in the relevant statute and regulations that exempted them from some provisions. These are typically grandfathered exemptions that apply statewide, or they relate to a commodity that

moves on vehicles on specific routes that otherwise exceed the provisions of the code or regulation (U.S. Department of Transportation, FHWA, 2004)

Access

49 USC 31114 defines and regulates access to the National System of Interstate and Defense; it states:

- Prohibition on Denying Access—A State may not enact or enforce a law denying to a CMV subject to this subchapter or subchapter I of this chapter reasonable access between—

- the Dwight D. Eisenhower System of Interstate and Defense Highways (except a segment exempted under Section 31111(f) or 31113(e) of this title) and other qualifying Federal-aid Primary System highways designated by the Secretary of Transportation; and

- terminals, facilities for food, fuel, repairs, and rest, and points of loading and unloading for household goods carriers, motor carriers of passengers, any towaway trailer transporter combination (as defined in Section 31111(a)), or any truck tractor-semitrailer combination in which the semitrailer has a length of not more than 28.5 feet and that generally operates as part of a vehicle combination described in Section 31111(c) of this title.

- Exception—This section does not prevent a State or local government from imposing reasonable restrictions, based on safety considerations, on a truck tractor-semitrailer combination in which the semitrailer has a length of not more than 28.5 feet and that generally operates as part of a vehicle combination described in Section 31111(c) of this title.

Waivers, Regulatory Relief, and Special Permits

Overweight permits for divisible and non-divisible loads under 23 USC 127 are special permits. FMCSR exemptions are waivers, or relief, from regulations. State or federal declarations may refer to both special permits and FMCSR exemptions in an emergency declaration. Part of the confusion regarding terminology surrounding the special permits a state can implement under 23 USC 127 authority has to do with other emergency powers under the transportation code. Specifically, 49 CFR 390.23 of the FMCSR, administered by FMCSA, includes provisions that occur when the president, governor, or local government issues a declaration of emergency under 49 CFR 390.5.

These exemptions to the FMCSR lift some safety regulations, including hours of service, for interstate motor carriers providing emergency relief. Additionally, utility service vehicles engaged in “operating, repairing, and maintaining” public utilities and government-owned vehicles always have an exemption to hours-of-service limitations under the FMCSR. FMCSA and USDOT, as well as states, refer to these exemptions to the FMCSR as waivers, exemptions, or regulatory relief.

The confusion in the freight community about special permitting under 23 USC 127 arises because many state declarations refer to both the special permitting process defined by 23 USC 127 and the exemptions/waivers occurring under 49 CFR 390.23. To be clear, waivers from the FMCSR occur under a different authority in the federal code (49 CFR 390.23) and often occur simultaneously with any special permitting a state implements under 23 USC 127. Further, a Stafford Act declaration can trigger FMCSR waivers for a set period following the declaration, or FMCSA can declare a regional emergency providing relief from 49 CFR Parts 390 to 399 (49 CFR 390.23, 2005).

Special permitting of OS/OW loads requires a Stafford Act declaration, and states must implement special permitting under federal and state statutes, and only for vehicles and loads delivering relief supplies. Thus, while FHWA may issue a statement or clarification regarding special permitting, states must act to implement that declaration as the permit issuing authority, whereas FMCSA possesses the authority to exclusively waive the FMCSR in some circumstances, a power the FHWA does not possess in regard to special permitting.

State Jurisdiction and Authority

State law regulates weight and size limits for vehicles traveling on roads within the state. State law also defines the state agency responsible for regulating OS/OW vehicles. The state agency granted authority under state law for vehicle permitting issues regulations and policies defining the process for obtaining permits. This permitting process is exclusively a state power since the federal government does not have the authority to issue permits for OS/OW vehicles.

Because the name and nature of the state agency regulating weight and size and the permitting process can vary from state to state, AASHTO refers to the agency issuing OS/OW general permits as the Truck Permit Issuing Office. Thus, while one state may grant authority to the state’s DOT, another may place that authority within a DMV or in a law or code enforcement agency like the State Police, Highway Patrol, or Department of Public Safety. In each case, that state’s responsible agency is referred to generally as the Truck Permit Issuing Office. In some states, the Truck Permit Issuing Office may be different than the agency responsible for regulating and enforcing weight and size restrictions.

A discussion of state weight and size laws and regulations appears in the next main section of this review, with state authority and regulation summarized in Appendix A.

Territory Jurisdiction and Authority

U.S. territories issue weight and size permits the same as states, via the Truck Permit Issuing Office.

Tribal Jurisdiction and Authority

Native American tribal nations participate in the Tribal Transportation Program (TTP) administered by FHWA, the U.S. Department of the Interior, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Division of Transportation (BIA-DOT). The BIA-DOT cooperates with tribal nations through contracts, grants, compacts, and other agreements under the authority granted in 23 USC 201 et seq. BIA regulations related to the TTP appear in 25 CFR 170 et seq.

BIA-DOT supports the operation and maintenance of BIA roads on native lands. BIA roads eligible for federal funding appear in the National Tribal Transportation Facility Inventory administered by BIA-DOT. Tribal nations establish rules and permitting procedures for OS/OW vehicles on BIA roads within their land (CRS, 2016, 2017). For example, the Mandan Hidatsa Arikara Department of Transportation (MHADOT) issues business permits and collects a transportation impact permit fee on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota. MHADOT also enforces vehicle weight regulations on the reservation and issues special permits and OS/OW permits (Mandan Hidatsa Arikara Department of Transportation, n.d.). Some tribal nations administer their roadways through a Department of Public Works rather than a DOT or through other organizations established by the tribal government. Some tribes may have agreements with state governments for permitting or enforcement.

In each case, the role of the tribal government in permitting and the measures it chooses to enact (or not enact) for truck permitting depend on the system of government established by the tribe as a sovereign nation, the treaty the tribe has with the U.S. government, and any agreements the tribal government may establish with state, county, or local governments. In other words, different tribes in different locations may have different systems in place for truck permitting and enforcement.

States may also establish liaisons or other tribal affairs offices to negotiate agreements between the state and tribal nations and coordinate state and tribal nation DOT regulations. For example, the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MNDOT) Office of Tribal Affairs coordinates and develops MNDOT “policies, agreements, partnerships, employment training, and contracts to create more efficient, improved, and beneficial transportation services with the 11 Tribal Nations in Minnesota” (MNDOT, n.d.). The MNDOT Office of Tribal Affairs also provides a training program to MNDOT and other state employees to learn about the state’s tribal governments, history, culture, and traditions to improve cooperation between state employees and the tribal nations.

State Truck Size and Weight Limit Regulations and Permitting

Federal Restrictions

In May 2015, the U.S. Secretary of Transportation submitted a report to Congress required by Section 32802 of PL 112-141, the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21) (FHWA, 2015). This report compiled state laws in effect on or before the enactment of PL 112-141 in October 2012 that allowed OS/OW vehicles to operate on the National Highway System (i.e., the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways). This study, conducted in partnership with AASHTO, examined those exceptions to weight limits in each state, including those authorized in the USC, and a list of all applicable limits, laws, and regulations in each state on weight and size limits.

As noted in the report, PL 97-424, the Surface Transportation Assistance Act of 1982, required several federal limitations for the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, including an 80,000-pound gross vehicle weight (GVW) limit, limits on truck tractor-trailer vehicle length limitations, and limits on tandem trailer combinations. Such limits by extension applied not only to the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways but to vehicles transiting state roads between terminals or service locations and the National System of Interstate

and Defense Highways since states, under federal law, must provide reasonable access to the interstate system.

PL 97-424 established several vehicle dimension requirements:

- States must allow vehicles 102 inches wide on interstate and other federally funded highways with 12-foot lanes.

- States must allow combination vehicles with semitrailers up to 48 feet and cannot prohibit the overall length of these combinations.

- States must allow trailers up to 28 feet in twin trailer combinations.

- States are prohibited from reducing trailer length limits in use and legal as of December 1, 1982.

PL 97-424 also prohibited states from imposing certain specific length limitations:

- No length limitations less than 48 feet on a truck tractor-trailer combination.

- No length limitations less than 28 feet on any trailer.

- No overall length limitations.

- No prohibition of commercial motor vehicles operating truck tractor-trailer combinations.

- No prohibition on trailers 28½ feet long in a truck tractor-trailer combination if trailer was in operation on December 1, 1982, and had an overall length not exceeding 65 feet.

- No limit less than 45 feet on the length of any bus.

Because previous legislation included many grandfathered provisions for certain overweight or overlength vehicles, PL 97-424 allowed states to issue permits for vehicles and loads “which the State determines could be lawfully operated in 1956 or 1975.” The grandfathered exceptions granted to states appear in 23 USC 127, while the specific grandfathered rights in any state related to semitrailer length and to combination vehicles exceeding 80,000 pounds GVW are in 23 CFR 658, Appendices B and C. Currently, 37 states and the District of Columbia have some form of exception to the 80,000-pound limit on at least some portion of their National System of Interstate and Defense Highways (FHWA, 2015).

Finally, in 1991, PL 102-240, the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act, fixed the weight of long combination vehicles and limited their routes to those allowed by a state as of June 1, 1991. The law defined long combination vehicles as “any combination of a truck tractor or two or more trailers or semitrailers which operate on the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways with a GVW greater than 80,000 pounds.” The law prohibited states from expanding routes or removing restrictions on long combination vehicles after June 1, 1991. Following the law’s implementation, states reported long combination vehicle size and weight restrictions that were in place before the freeze. Additionally, states reported authorized routes for long combination vehicles, now listed in 23 CFR 658. Currently, 23 states allow long combination vehicles, but six of those states limit the operation of long combination vehicles to turnpike facilities (FHWA, 2015).

State Weight Limit Compliance with Federal Limits

Because 23 USC 127 could lead to the withholding of federal highway money in a state that sets weight limits for travel on the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways that are higher or lower than the federal limits, many states incorporated compliance clauses into state law that maintain compliance with 23 USC 127 requirements in some manner (FHWA, 2015).

However, most states establish two sets of weight limits, one for state highways and another for interstate highways, with the latter either being compliant with 23 USC 127 or otherwise triggering a compliance clause. For example, in 2012, FHWA identified eight states (Connecticut, Hawaii, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Washington, and Wyoming) in which the state’s statutory weight limits were higher than the federal limit for interstate highways, but the compliance clause applies the federal weight limit to the interstates, thereby overriding the state weight limit for interstate travel (FHWA, 2015).

State Permitting Processes and Weight/Size Limits

While harmonization efforts exist across the United States to implement more uniform practices for OS/OW permitting and marking/escort requirements, states issue these permits differently or do not use the same agency. Furthermore, although weight limits for the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways are uniform due to compliance clauses designed to maintain compliance with 23 USC 127 and therefore prevent any loss of federal highway funding, state highway weight limits vary widely. Consequently, even if a state harmonizes its escort, marking, or lighting requirements with another state, the permitting process and the limitations on state roads may still vary.

Additionally, county and municipal governments may require, or attempt to require, their own limitations on county or municipal roadways. Both Middleton et al. (2012) and Prozzi et al. (2014) found variations not just within the state but between transportation districts within the state regarding OS/OW permit requirements and practices.

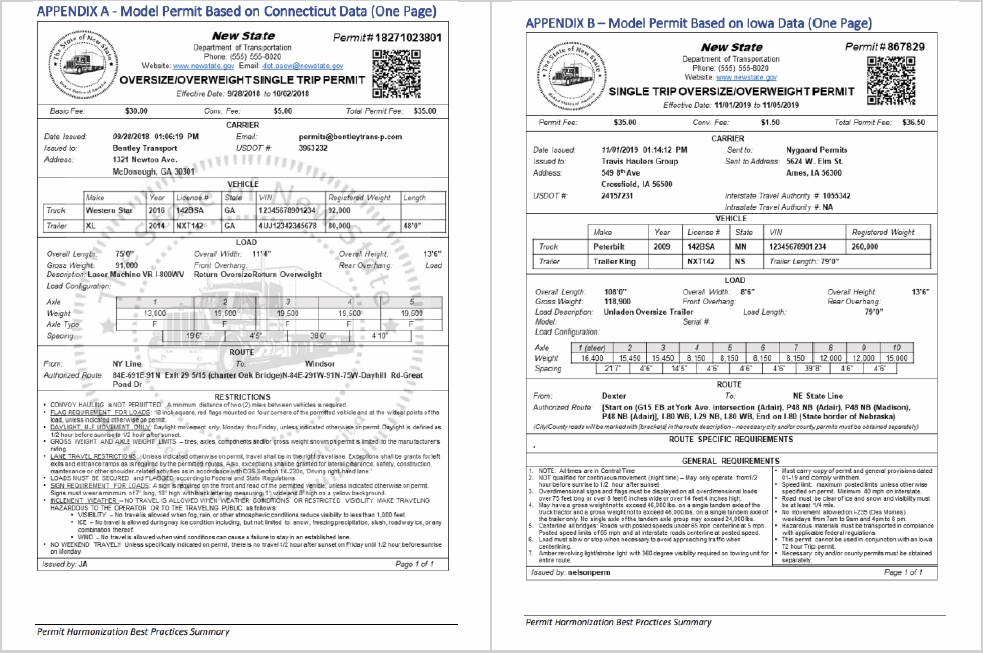

A complete survey of state permitting processes and weight/size limits, as of October 1, 2012, appeared in the FHWA MAP-21 Report to Congress, Compilation of Existing State Truck Size and Weight Limit Laws. The FHWA Office of Freight Management and Operations maintains a contact list of state permitting offices on its webpage. The office also provided clarification on special permit expiration under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act. AASHTO has a 50-state matrix of permit requirements on its OS/OW Permit Harmonization webpage, with additional information on those harmonization efforts at the national and regional level, which are discussed further in the section below.

Additionally, AASHTO (2016) publishes the Guide for Maximum Dimensions and Weights of Motor Vehicles, currently in its fifth edition. Regional state highway and transportation associations, like WASHTO, also publish guides. In addition to recommendations for permit harmonization efforts, WASHTO identifies some of the regional variations in permitting practices and weight/size limits.

However, these guides, discussed more in the next section, focus on recommendations to the states. There are no freely available, regularly updated U.S. or North American guides to state permitting requirements for OS/OW vehicles and the various state limits and practices. The most

recent public domain survey of state permitting is an e-supplement prepared by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) in support of its 2015 report, GAO-15-236: Transportation Safety: The Federal Highway Administration Should Conduct Research to Determine Best Practices in Oversize/Overweight Permitting (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2015). The related study found, based on the data gathered for the e-supplement and the report, wide variations in state permitting practices. GAO recommended research and development by FHWA of best practices guidance with an emphasis on automated permitting systems.

Private-Sector Solutions

To address the gap in publicly available information on current permitting practices, limitations, and requirements, private-sector firms provide fee-based services to trucking and shipping companies to assist them in routing and permit acquisition. These firms specialize in providing routing information, providing safety and marking requirements, and identifying any travel restrictions (like days/times of operation limitations along the route), and they provide assistance in obtaining the necessary permits.

Additionally, some of these permit firms provide escort vehicles, pilot cars, route surveying, or other services. These firms may work as a network of subcontractors—small companies specializing in specific states or regions—or as larger firms that assist with international shipments into Canada and Mexico and their associated permitting processes and requirements. Additionally, several firms offer subscription-based regulatory search tools and guides to OS/OW permitting and state weight/size limits, including the Oversize Load Assistant and J.J. Keller and Associates’ Vehicle Size and Weight Guidelines—Online Edition.

Best Practices and Harmonization of Regulations

Harmonization efforts at a regional and national level, like the 2009 WASHTO guide, have a long history. NCHRP first published a synthesis of uniformity efforts in OS/OW permits in 1988 (Humphrey). Following the passage of PL 112-141 in 2012, AASHTO’s SCOHT (predecessor of the Subcommittee on Freight Operations) and several regional state highway and transportation organizations engaged in efforts to harmonize OS/OW permitting between states to reduce impediments to interstate commerce. The recommendations of these organizations—provided to state officials—encouraged the states to adopt standard procedures for escort vehicles, signage, flags, warning lights, travel restrictions related to days/hours of operation, holiday travel restrictions, permit maximums, permit revision and extension processes, and the time a permit is valid for a single state trip.

SCOHT defined harmonization as establishing “baseline restrictive thresholds for various characteristics of an issued permit” that allowed and encouraged states to find “appropriate, less restrictive, measures” (AASHTO, 2016). SCOHT focused on two core concepts in its efforts, with harmonization rather than uniformity as a goal: first, that states agree not to become more restrictive in their permitting process than they were when AASHTO began its harmonization effort; and second, that states agree not to be more restrictive than an agreed-on base level or threshold approved by SCOHT by “established voting processes.” Both of these principles came with the caveat “where practicable.”

Unfortunately, AASHTO SCOHT members, although representing their states, could not change the permitting regulations without action by state legislatures or through established rulemaking procedures within their states. SCOHT recommendations asked states with permit conditions more restrictive than those of the SCOHT harmonization recommendations to “review their laws, regulations, and polices” and “consider changing them as appropriate to reach the threshold” (AASHTO, 2016). However, state permit issuing offices, regulatory authorities, and legislatures had no legal obligation to do so.

Although the SCOHT efforts to harmonize markings, lighting, and escorts achieved some successes as to base levels/thresholds, wide variations remain in permitting practices, permit requirements, route planning, and size and weight limits from state to state, between state practice and that of federally recognized tribal governments and U.S. territories, and between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, as further studies have demonstrated.