Developing a Guide for Transporting Freight in Emergencies: Conduct of Research (2024)

Chapter: 3 State of the Practice

Chapter 3. State of the Practice

Introduction

The research team developed a hybrid approach for this portion of the study, involving an online survey of various stakeholders and following up with phone interviews and virtual workshops involving key respondents to the survey. This process allowed researchers to collect information from state permitting agencies and other stakeholders (FHWA, FMCSA, etc.). This approach ensured broader and more diverse participation and a higher quality outcome.

Researchers conducted the online survey, interviews, and virtual workshops between March–May 2023 to (a) compile best practices, procedures, and decision processes for increasing weight limits during emergencies used by state and local transportation agencies; (b) determine the rationale behind these processes, practices, and decision processes; and (c) understand and document best practices for harmonization with neighboring jurisdictions. Specifically, the questions developed for this hybrid approach documented the following:

- Stakeholder’s key concerns regarding the movement of overweight trucks during emergencies.

- Agency understanding of emergency and emergency commodities.

- Agency department and staff positions responsible for emergency coordination with nearby states and local agencies.

- Agency lessons learned from implementing emergency special permits for overweight trucks.

- Best practices implemented by stakeholders during emergencies.

The research team shortlisted and performed outreach to diverse stakeholder members (in terms of background and geography). This process included contacting representatives from state Truck Permit Issuing Offices, which as noted above can vary in different states. Thus, researchers contacted five DMVs—Connecticut, Maine, Texas, Vermont, and Virginia; two Departments of Public Safety—Georgia and South Dakota; two Highway Patrols—North Dakota and Wyoming; and 41 DOTs. Prior to conducting this outreach effort, researchers developed survey and interview questions. Researchers then submitted and received approval for these questions, along with the stakeholder list, from the NCHRP research panel.

The research team distributed the online survey to each state’s Truck Permit Issuing Office, with a request to forward the invitation to an appropriate staff member responsible for permitting OS/OW loads. Figure 5 shows the first page of the online survey. A copy of the survey transmittal letter and a full list of survey questions is in Appendix B.

The online survey contained 13 questions with nested logic (i.e., the questions changed based on the survey responses). Researchers also developed another list of follow-up interview questions to elicit more in-depth responses from the agencies implementing best practices or those struggling to implement best practices. Stakeholder interviews and survey responses allowed the research team to better understand the processes, procedures, and challenges faced by Truck Permit Issuing Offices when issuing special permits during emergencies and disasters.

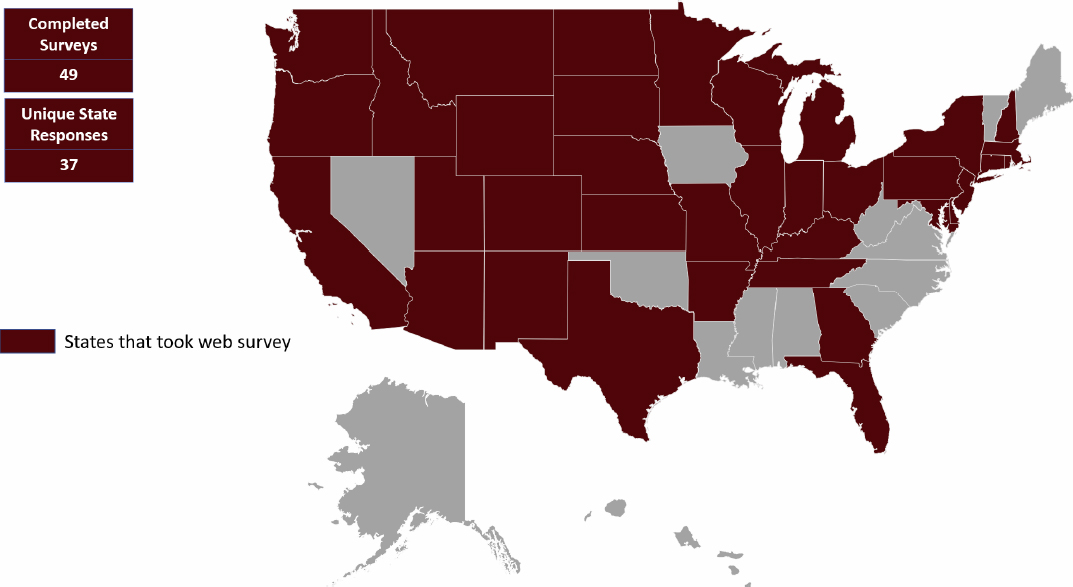

The research team received 49 survey responses, but three of these were incomplete. The 43 responses contained identifiable state information, some of which involved duplicate responses from the same permitting agency. In total, 37 unique state responses were obtained, as shown in Figure 6.

The list of responding agencies is included in Appendix C, along with a full list of survey responses, grouped by question. The following section summarizes key findings from the survey.

Survey Results

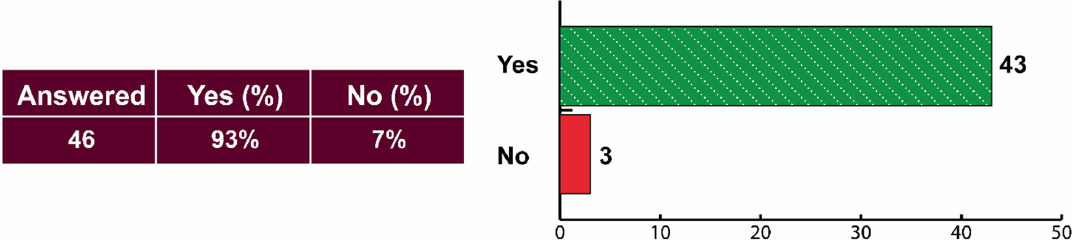

Figure 7 shows the results of the first question on the survey regarding whether the respondent works for the state OS/OW permitting office/authority and is knowledgeable about permitting and policies for commercial vehicles during emergencies. Out of 46 respondents, three respondents indicated that they were not knowledgeable or did not deal with OS/OW permitting. Detailed survey responses are in Appendix C.

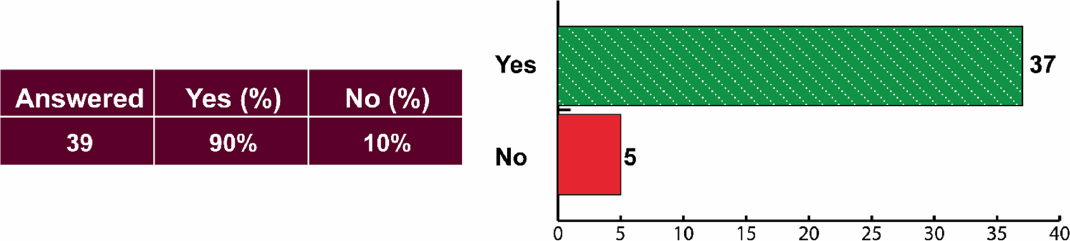

Figure 8 shows that 37 respondents issued special permits for commercial vehicles for prior emergencies or disasters. Four respondents indicated they had not previously issued special permits.

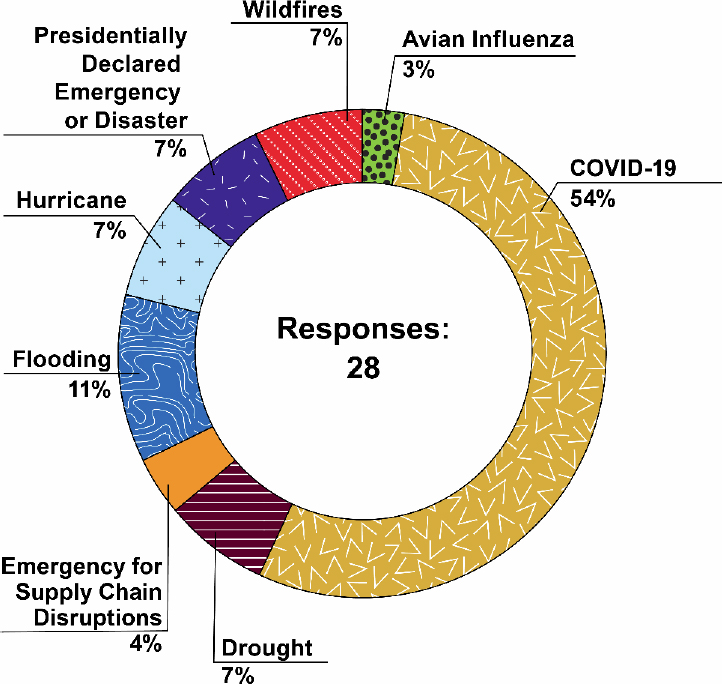

Figure 9 shows the most recent kinds of state-level emergencies where the state implemented special permitting. Twenty-eight respondents, a 54 percent majority, issued special permits during COVID-19. Based on the surveys and previously discussed analysis performed on emergency declarations posted to the CVSA emergency declaration website, since 2020 there has been a gradual increase in emergencies related to flooding, hurricane, drought, snowstorms, and wildfire (also see Figure 4 in the previous chapter).

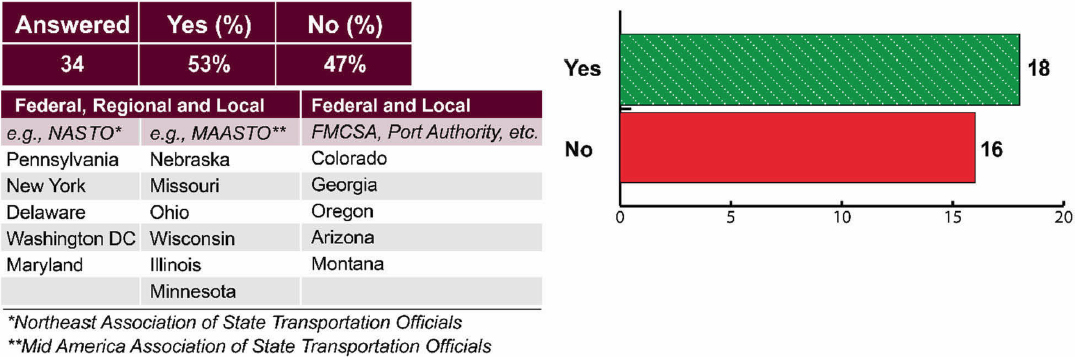

Figure 10 shows a breakdown of responses to the question about coordination of the special permits with other states or agencies. Around half of the Truck Permit Issuing Offices stated they conducted coordination with other states or agencies. Respondents listed coordination with federal agencies (FMCSA, FEMA, FHWA, etc.), state emergency management agencies, local agencies (cities, counties, etc.), and independent commissions and quasi-governmental bodies (port authorities, councils of government, etc.). It was observed that NASTO and MAASTO states coordinated among themselves with the federal, regional, and local levels, whereas some states coordinated only with local and federal agencies.

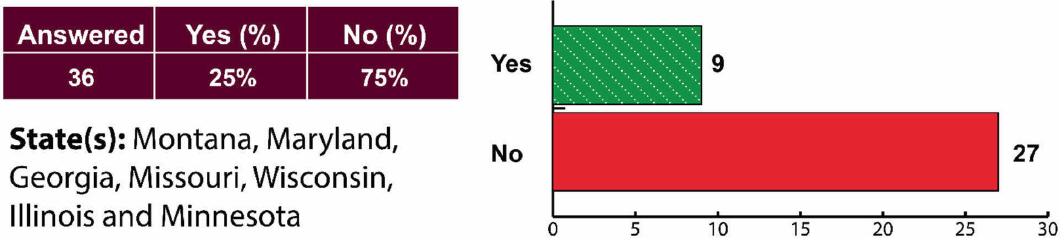

As shown in Figure 11, 25 percent of responding Truck Permit Issuing Offices (out of 36 who responded) initiated changes to vehicle overweight laws, regulations, or policies during emergencies or disasters.

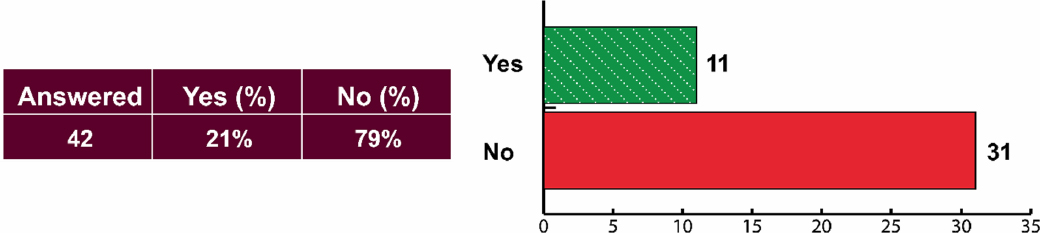

Figure 12 shows that 21 percent of the responding Truck Permit Issuing Office (out of 42) had been impacted by special permits issued by another state during an emergency. Not every respondent answered this question.

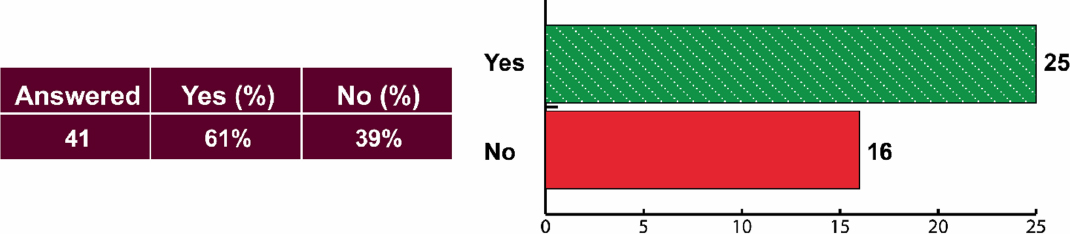

Figure 13 shows that 61 percent of responding Truck Permit Issuing Offices had some sort of outreach or education program with the trucking industry to conduct education and provide assistance with overweight special permits.

Phone Interviews

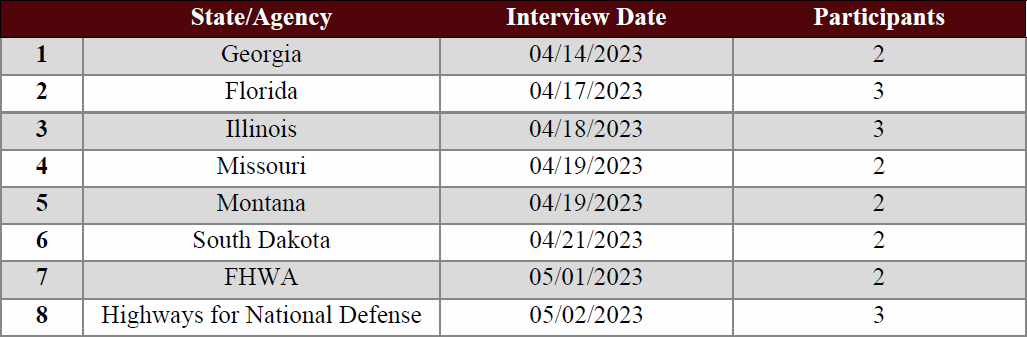

Following the survey, researchers conducted interviews with the online survey participants based on their responses. The questions used in these phone interviews are listed in Appendix B. The research team sent emails to potential interviewees, and based on responses, researchers set up phone interviews and asked questions. The questions focused on understanding best practices and lessons learned about overweight special permitting during disasters and emergencies. Table 5 shows the state or agency interviewed and the date researchers conducted the interviews.

Virtual Workshops

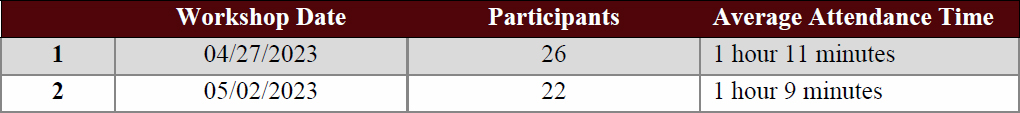

The research team conducted two invitation-only virtual workshops that allowed brainstorming and the opportunity to bring multiple perspectives to the table. Researchers selected workshop dates by polling the potential participants identified in cooperation with the research panel. Two dates worked based on the availability of participants needed to reach a critical number of greater than 20 persons (as shown in Table 6).

These virtual workshops used video conferencing software (i.e., Microsoft Teams) and screen sharing for consensus-building. The research team engaged stakeholders with questions and scenarios to gain an understanding of the variety of approaches used for OW special permitting during emergencies and how state agencies conducted inter- and intra-agency coordination during disasters (see Figure 14). The workshop also tried to map information flows during a disaster. Additionally, researchers and participants examined ways to develop a coordinated emergency plan that might inform the decision support framework developed in Task 5 of this project.

Interview with the Department of Defense

The research team also interviewed representatives with the DoD for their perspective on special permits during a national emergency or disaster. Several issues emerged in discussions with DoD

representatives regarding their requirements for shipping OS/OW loads. These issues occurred in the continental United States during normal operations, during DoD and state National Guard operations supporting civil authorities in presidential declared disasters, and during times of war when DoD vehicles moved to deployment ports. These issues are further discussed below.

During some national emergencies, the DoD needs to move significant quantities of material and equipment to designated ports for shipment overseas. Contracted civilian carriers must draw permits for some of these loads. This process may limit the amount of material moved, given the necessity of complying with state OS/OW permitting requirements. Because states have no authority to issue special permits without a presidential disaster declaration, the DoD cannot exempt these shipments from state permitting requirements, even though the loads directly support a declared national emergency and may require urgent handling, since present special permitting authority (outside of the Bangor, Maine, exception) does not exist in federal law or regulation for wartime or operations other than war.

Some state National Guard and active-duty military forces involved in support to civil authorities during state or presidential declared disasters also may not understand the overweight special permitting processes in the states affected by the disaster or the states transited to get to the affected states.

The DoD has an ongoing project to review the deployment routes used by current military installations to reach their embarkation ports in emergencies/times of war. To date, this review discovered several issues, including plans for roadways or designated routes serving former military installations, state or federal roads with infrastructure and bridges that cannot support the weight of especially heavy military vehicles or trucks carrying such vehicles, height restrictions created by newer bridges or overpasses, and assumptions about the availability of trucks and drivers to deliver material to points of embarkation.

The military rarely has organic OS/OW permitting requirements but still requires state permits for convoy operations. For these permits, the military uses Transportation Coordinator’s Automated Information for Movement System II (TC AIMS II), an internal military system, to coordinate and approve convoy movements, including routes and permits to ensure a harmonious movement across multiple states and jurisdictions. Each state’s defense movement coordinator (DMC) is responsible for coordinating permits within the state, but the TC AIMS II system provides visibility to deconflict potential external state issues before they can impact the larger movements. The TC AIMS II and DMC concept may offer a potential template for creating an emergency civilian movement coordination system to support national and regional emergency overweight shipments. FHWA suggested this approach in the past.

The domestic commercial trucking requirements that support a military deployment or the movement of most military equipment falls below the level of a national declaration of war that might authorize extraordinary measures or waive certain restrictions.1 As such, for most military movements, the commercial carrier is responsible for coordinating all OS/OW permit requests.

___________________

1 The last Congressionally declared war on another nation was the U.S. declaration of war against Japan following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Since World War II, Congress authorizes U.S. military operations through the War Powers Act and appropriations without declaring war.

The individual carriers or their subcontracted companies are at the mercy of individual states and regional permitting consortiums for coordination and approval of their loads and routes, which may impact military deployments or support to ongoing operations.

The DoD can benefit from the ability to use an emergency civilian movement coordination system during national and regional emergencies as well as for operational deployments and national defense requirements that fall below the declaration of war. At present, emergency powers related to the NEA do not address such situations beyond a specific route on I-95 that supplies fuel to a Maine Air National Guard base in Bangor, Maine.

Because the DoD currently lacks emergency movement authority under the existing emergency powers law for emergency OS/OW shipments absent a declaration of war, it may be necessary for elected officials or FHWA to pursue special rulemaking to address this deficiency and establish an expanded system of special permitting to address DoD overweight shipments outside of a Stafford Act or other national emergency powers declaration. Another potential solution may be for lawmakers to include language addressing overweight shipments by both military vehicles and commercial shippers under contract to the DoD in any authorization for the use of military force or national emergency declaration.

Related Policy Efforts

The Safer Highways and Increased Performance for Interstate Trucking (SHIP IT) Act was introduced in the U.S. House by Dusty Johnson (R-South Dakota) and Jim Costa (D-California) on January 24, 2023. The status of this effort is unclear; however, it includes the following provisions that might assist in resolving some of the special permitting issues identified in this study:

- Modernize the authority for certain vehicle waivers during emergencies.

- Allow truck drivers to apply for Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act grants.

- Incentivize new truck drivers to enter the workforce through targeted and temporary tax credits.

- Expand access to truck parking and rest facilities for commercial drivers.

- Streamline the commercial driver license (CDL) process, making it easier for states and third parties to administer CDL tests.

- Exempt electric vehicle battery weight from gross weight for certain regulatory purposes.

- Create a voluntary pilot program to permit states to allow 91,000 pounds on six-axle trucks on interstate highways.

- Provide a 150-air-mile exemption from hours-of-service regulations for haulers of agricultural commodities, unprocessed products, and processed products.

Summary and Conclusions

The following discussion identifies preliminary and general trends observed in the survey results and further documented as part of the interviews and virtual workshops.

Preliminary Findings

Researchers identified the following significant findings related to OW special permitting during disasters, with potential solutions drawn from the research project tasks and stakeholder input:

Definition of Emergency and Emergency Commodities

The Truck Permit Issuing Office’s understanding of emergency and emergency commodities comes from the definition used in the state governor’s executive order (per state statute), the president’s Stafford Act disaster declaration, or as stated by the state emergency management authority or FEMA. For most permitting offices, involvement in defining the emergency or emergency commodities rarely occurs.

There is no single generic list of emergency commodities, and the commodities needed depend on the nature of the emergency. That said, a number of emergency declarations resulting in OW special permitting were commodity specific, usually related to harvests or a particular commodity shortage like fuel, heating oil, or propane. Misunderstandings as to what commodities were and were not covered by any declaration resulting in special permitting led to confusion and potential abuse of the special permitting process to move overweight divisible loads that may not qualify as emergency supplies. This led to confusion among shippers and commercial vehicle enforcement officers and poses potential road damage issues that may not be related to the disaster in question.

Potential Solution: Emergency Commodity Lists

For emergencies affecting specific commodities (grain, fuel, etc.) language specifying those commodities should appear in both the disaster declaration and on any special permit. For other disasters requiring a diverse mix of commodities in divisible loads, Truck Permit Issuing Offices and state emergency management should work with FEMA and other federal agencies to develop lists of affected commodities needed in major, well-known disasters (like hurricanes or wildfires) and include those lists with special permits and provide to commercial vehicle enforcement agencies to ensure compliance.

Variation in Special Permit Issuance

There are variations in how states issue permits, depending on the Truck Permit Issuing Office’s available resources and staffing. For instance, some states have in-house permitting systems for emergencies, some utilize third-party vendor products, some have a customizable template form for emergencies, and a few others have a blanket emergency permit without specifics. One state has an emergency permit shippers can apply for before emergencies and maintain in their vehicles that specifies it becomes effective if accompanied by a state or presidential disaster declaration. Another state has a policy that the state declaration serves as the special permit in emergencies.

Potential Solution: A Menu of Solutions

Some state permitting agencies developed applications and processes tailored to issuing special emergency permits (Illinois). These systems provide the necessary information regarding the permit and what it covers to carriers and commercial vehicle enforcement officers. Other states use blanket permit systems (like those mentioned above).

Case studies of each may be required to develop models that fit specific state needs. Because of the varied nature of emergencies and disasters, and significant variances in state regulation covering special permitting in those situations, state regulatory requirements and enforcement expectations associated with the different models may prevent a single national model for emergency permitting.

Different Enforcement Standards

Commercial vehicle enforcement during emergencies may also depend on available resources. Some states have lenient mechanisms that allow law enforcement officers and the shipper to individually interpret the OW/divisible shipment requirements and whether the load complies with the law and disaster declaration. For example, a governor’s disaster declaration is a permit in some states. In contrast, other states require the carrier to carry a general permit and the current emergency declaration. Different states have stricter issuance and enforcement requirements regarding when a carrier must apply for a special permit in each disaster/emergency and what that permit allows.

Some states issue general OW special permits that become valid during a presidential or state-declared emergency or disaster. These usually require the declaration with the general permit to be valid. This practice, while streamlined for efficiency, raised significant issues for enforcement officers since drivers or companies sometimes treated the general permit as a semi-permanent exemption outside of the period of a declared disaster.

Additionally, some commercial vehicle enforcement officers reported using the CVSA declaration portal to check permits, especially those from out of state. These officers reported misuse or misunderstanding regarding those permits and the use of expired permits beyond the date of the declared disaster (where an extension did not occur or was not included with the permit).

Potential Solution: Increased Education and Outreach

The impact of lenient mechanisms on neighboring states and the potential for safety issues require further study before making any recommendations. One model may not serve all U.S. states or regions.

The use of the CVSA declaration portal and education efforts to encourage its use by commercial vehicle enforcement officers in all states could improve enforcement efforts. Additionally, there is a clear need to increase education efforts for carriers using special permits, especially those operating out of their normal service areas, across state lines, or in places where they lack knowledge of the permitting requirements in that state.

Confusion Regarding FMCSR Waivers

The language in governors’ emergency declarations can sometimes confuse carriers and authorities. Because many states combine declarations waiving the FMCSR (a federal-only waiver) and OW special permitting, carriers may presume one, the other, or both conditions apply when they do not.

Potential Solution: Increased Interstate Coordination and Declaration Standardization

AASHTO and CVSA’s engagement with the National Governors Association may allow for the creation of standardized emergency declaration language agreements or sample OW special permitting declarations.

Confusion About Restricted Loads and Routes During Emergencies

Although regular OS/OW carriers understand the restricted load requirements, carriers operating with overweight loads during emergencies may not regularly carry OS/OW loads and therefore may not understand the importance of restricted load requirements. State Truck Permit Issuing Offices should provide the carriers receiving a special permit with written instructions on routing and safety compliance. Likewise, states do not have the authority to issue special permits for the interstate highway system without a presidential disaster declaration and thus, state-level declarations only affect specific state roads. Some states may only authorize OW special permit loads to travel exclusively on the interstate system and not allow those carriers access to state roads when transiting through the state to another state where the disaster declaration applies.

Potential Solution: QR Codes and Weblinks

Among best practices examined, the use of special permit QR codes appeared the most promising. These QR codes embedded in a special permit link to routing and other information carriers and drivers need when moving loads on special permits. The ability to readily update that information on a website allows Truck Permit Issuing Offices to dynamically adjust routing depending on conditions or road closures in a disaster or modify a special permit if the disaster is extended, the permit modified by later declarations, or when specific commodities involved change due to the needs of the response.

Further, such information access may provide drivers and carriers not used to frequently operating with overweight loads a more ready resource for understanding permit restrictions. Another benefit of the QR code is that both commercial vehicle enforcement officers and carriers can use it. Enforcement officers can quickly verify the permit, route information, commodities covered, and the period of permit validity via a cellphone or other Internet connected device with a QR code reader application.

Although the CVSA disaster/emergency declaration website allows carriers/drivers to filter declarations to aid their understanding of roadway authorization (i.e., exclusive use of the interstate highway system), the implementation of standardized language or sample orders and education programs to instruct carriers and drivers on the specifics of permit authorization is necessary to improve compliance.

Standardized Communication Processes

Communication is vital during an emergency, and while informal communication channels offer some efficiencies, they may fail in a crisis. Interpersonal relationships form informal communication networks between neighboring states, agencies, and regular OS/OW carriers. In an emergency, personnel and carriers may come from many places, including out of state. They may not have experience with overweight shipping or connections to that state’s Truck Permit Issuing Office or those they may transit through to reach the disaster.

Although state and trucking associations use various communication mechanisms for communicating about special permits during an emergency, few use anything resembling a formalized system, and most use informal networks developed from working regularly with instate or neighboring state shippers. A few existing regional coordination mechanisms or something akin to the DoD DMC notification process inherent to their permitting, route, and convoy system might serve as a model.

Additionally, most Truck Permit Issuing Offices lack an understanding of emergency management communications and the organizing structures used by emergency management and first responders, encapsulated in the National Incident Management System (NIMS). This limits their ability to communicate and coordinate with state and federal emergency management in a disaster, especially one that affects a wide area.

Potential Solution: Formalize Communication Networks and Align with FEMA Standards

In addition to publicizing and educating emergency management officials, shippers, inter- and intrastate commercial carriers, and Truck Permit Issuing Offices on the efficacy of the CVSA Emergency Declaration Portal and the importance of timely submissions to that system, state emergency management agencies, state DOTs, and Truck Permit Issuing Offices should establish uniform, formal communication and organizing principles for emergencies and disasters.

National trucking organizations, the National Governors Association, and FEMA should consider developing and incorporating such procedures into NIMS and future emergency management documents. Additionally, these organizations should coordinate with FEMA to create a FEMA Emergency Management Institute Independent Study training course for emergency management, transportation officials, CMV Enforcement, and Truck Permit Issuing Offices on emergency waivers of the FMCSR and special permitting for overweight emergency commodity shipments during declared disasters and other state emergencies.

Definition of Divisible and Non-divisible Loads

The state issues special permits during emergencies with a clear understanding of divisible and non-divisible loads. However, what constitutes divisible and non-divisible loads may be misunderstood by nontraditional OS/OW carriers applying for special permits in emergencies. Likewise, shippers and carriers may know state-specific permitting requirements when the carriers or shippers are in or from other states or organizations unfamiliar with special permitting in other states.

Potential Solution: Provide AASHTO Examples

AASHTO is already developing clear examples for divisible and non-divisible loads. Truck Permit Issuing Offices should consider including these on their office/permitting websites or provide links to the AASHTO examples when complete and made public.

Confusion About Safety Requirements

There is confusion in the freight community regarding special permits and FMCSR waivers for carriers and truck drivers. State permitting agencies seem clear that safety requirements do not change irrespective of weight requirements during an emergency.

Potential Solution: Development of training and informational fliers and worksheets for the trucking industry is recommended.

Department of Defense Related Solutions

Multi-state Notification of Interstate Movements of Special Permitted Loads

The DoD utilizes a system for convoy movements, TC AIMS II, that allows transportation officers to construct convoys in the system designating vehicle types, weights, and dimensions (drawing from a database containing that information for each vehicle). Once users specify their origin and destination, the system displays routing information and alerts each state DMC along that route to coordinate with their state authorities and, if needed, obtain the necessary OS/OW permits from the state’s Truck Permit Issuing Office. DMCs are appointed military transportation officers or civilian employees in each state’s National Guard that coordinate military movements with each state DOT.

Potential Solution: TC AIMS II

The TC AIMS II system is a potential model for coordinating interstate OS/OW special permit planning and permitting. Further study may be necessary to determine applicability. Still, the model of cross-state notification could potentially streamline regional or national emergency permitting in a presidentially declared disaster involving multi-state movements.

Road Infrastructure for Oversize/Overweight Movements

Although the DoD is involved in an ongoing program in coordination with states and DOTs to improve state and national highways to better support movements of military equipment to embarkation points, some of the same issues the DoD faces may affect emergency shipments of material or equipment during presidentially declared disasters. Examining routing, especially in disaster-prone areas like hurricane zones, could identify similar infrastructure issues that may affect the overweight movement of emergency supplies in a disaster, and improvements to infrastructure may be advisable in some disaster-prone areas based on routing assessments.

Potential Solution: Improvement Programs on Designated Routes

Hurricanes are a significant and regular disaster faced by many coastal states in the eastern and southeastern United States. These areas are also home to many DoD facilities and designated Ports of Embarkation. Given the ongoing program by the DoD to improve state and national highways and routing to support their movements from DoD bases to ports that may be hit by hurricanes, coordinating DoD specific improvements to infrastructure with those necessary to support broader disaster efforts could provide significant benefit. Further, given that such routes are assessed for overweight loads, state DOTs and Truck Permit Issuing Offices should consider those routes for the shipment of overweight divisible load emergency supplies during disasters and may wish to incorporate them into any disaster supply routing implemented as part of special permitting.

Oversize/Overweight and Emergency Routing in Disasters

Potential Solution: Solution Similar to DoD Intelligent Road and Rail Information System

The Intelligent Road and Rail Information System (IRRIS), developed in 1999 and used by the DoD for many years, could potentially be a platform on which to base OS/OW routing during disasters. According to the DoD, “IRRIS is a Web-based system that uses information technology to enable military users to obtain detailed, timely, and relevant information about road conditions, construction, incidents, and weather that might interfere with the movement of personnel and cargo from origin to ports through a user-friendly browser interface on the Internet” (DTR, 2016). This system, which FEMA signed an MOU to use in 2007, could provide a basis for routing in a major disaster or emergency involving intra- or interstate movements of OW divisible and non-divisible loads, as well as in support of emergency transportation management more broadly.

That said, IRRIS no longer exists as a DoD program. According to Transcom, many of the programs it previously used, like IRRIS, migrated to a new and different government developed geographic information system collectively known as the Transportation Geospatial Information System (TGIS), which is used primarily for tracking military shipments, though it does offer situational awareness for weather and other potential impediments to military moves, primarily relying on an ESRI Enterprise-based ArcGIS system to display ESRI and custom datasets (some, like weather, in real time). The TGIS system no longer provides some of the functionality described as contained in IRRIS.

During this project, researchers were unable to assess IRRIS as it used to exist. However, IRRIS was a commercially developed system, and a private firm, GeoDecisions in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, that developed IRRIS, still maintains a login website at https://irris.geodecisions.com/web/login.aspx. It may not function as it once did, but conceivably it or a similar third-party application may provide similar functionality to that described in previous DoD reporting.

DoD Domestic OS/OW Movements in Operations Other Than War

Potential Solution: Regulatory Change or Language Inclusion in Authorizing Legislation

Policymakers and regulators may also wish to consider amending the USC or federal transportation regulations to allow the DoD to conduct emergency OS/OW special permitting absent a presidential disaster declaration but in a national emergency. Alternatively, Congress may consider granting the president powers to include such measures in declarations of national emergency, or they may wish to have appropriate language in an authorization for the use of military force absent the declaration of war.