Accommodating Peer-to-Peer Carsharing at Airports: A Guide (2024)

Chapter: 9 Overview of Business Agreements with P2P Companies

CHAPTER 9

Overview of Business Agreements with P2P Companies

The following paragraphs summarize examples of the requirements included in airport business agreements with P2P companies on the basis of a review of agreements obtained from the airports serving Denver, Salt Lake City, and Tampa, as well as other airports.

9.1 Term

A review of existing airport business agreements with P2P carsharing companies indicates that these agreements typically include a term of 1 year with options for annual extensions. Many of the agreements reviewed also include the ability of an airport to terminate the agreement without cause upon 30- or 60-days’ written notice from either the airport or the P2P company. Terms may also be on a month-to-month basis until terminated by the P2P company or airport operator.

9.2 Requirements of the P2P Company

Airport business agreements typically specify the following requirements of a P2P carsharing company:

- Limit customer drop-offs and pickups to a “Designated Area” or “Licensed Area,” a physical area defined in the agreement or an attachment to the agreement.

- Require that vehicle owners use only the Designated Area for customer pickup and drop-off.

- Inform P2P vehicle owners of the airport’s rules and regulations and any changes to these rules and regulations.

- Require P2P vehicle owners to comply with the airport’s rules and regulations.

- Require P2P vehicle owners to obey the lawful commands of airport staff or a police officer or provide requested information to these individuals.

- Display the details of the Designated Area and approved permitted uses on the company’s website.

- Perform a criminal background search and a public records search of any owner flagged for fraudulent or criminal activity and “lock down” the owner’s account until the owner clears the background check.

- Investigate vehicle owners who may have violated the permitted uses or do not comply with the required use of the designated areas (e.g., vehicles found outside the Designated Area) and confirm such violations to the airport.

- Ensure that vehicle owners maintain their vehicles in a clean and neat condition and that vehicles are safe for operation.

- Evaluate the safety of the owners’ vehicles and check the VIN for safety recalls.

- Agree not to conduct any business other than P2P carsharing business on airport property.

- Ensure that vehicle owners will not solicit business at the airport and the vehicle will not display advertisements soliciting business.

- Require owners to exhibit the highest standards of integrity, reliability, and courtesy when interacting with airport passengers and customers.

- Prohibit owners from

- Renting out vehicles other than the types of vehicles defined in the agreement,

- Circumventing the company’s website,

- Allowing operation of the owner’s vehicle by an unauthorized driver,

- Transporting a customer in an unauthorized vehicle,

- Recirculating on the airport terminal curbside roadways, and

- Failing to obey posted speed limits and traffic regulations.

- Penalize or fine any owner who disobeys airport rules and regulations, with the amount increasing after each offense.

9.3 Reserved Rights of Airport Management

Airport business agreements with P2P carsharing services typically state that airport management reserves the right to

- Revise the size and location of the Designated Area from time to time.

- Suspend a vehicle owner from the property for violations of the airport’s rules and regulations.

- Inspect the vehicles operated under the agreement with respect to passenger access, vehicle registration and license, owner’s driving license, vehicle insurance, and other matters pertaining the legal, efficient, and safe operation of the owner and the vehicle at the airport.

9.4 Airport Fees

Each business agreement reviewed requires that P2P carsharing companies pay fees to conduct business on the airport. The agreements state that

- The P2P company agrees to pay the airport a privilege or concession fee calculated as a percentage of gross receipts derived from the company’s airport operations. Though the amount of the privilege fee initially varied among airports, most agreements reviewed for this research require the P2P carsharing company to pay a fee of 10 percent. Of the agreements reviewed, the only airports not charging 10 percent were Tampa (8 percent) and Tallahassee (6.5 percent) international airports.

- Hosts and customers pay any parking fees for use of the designated airport parking facility.

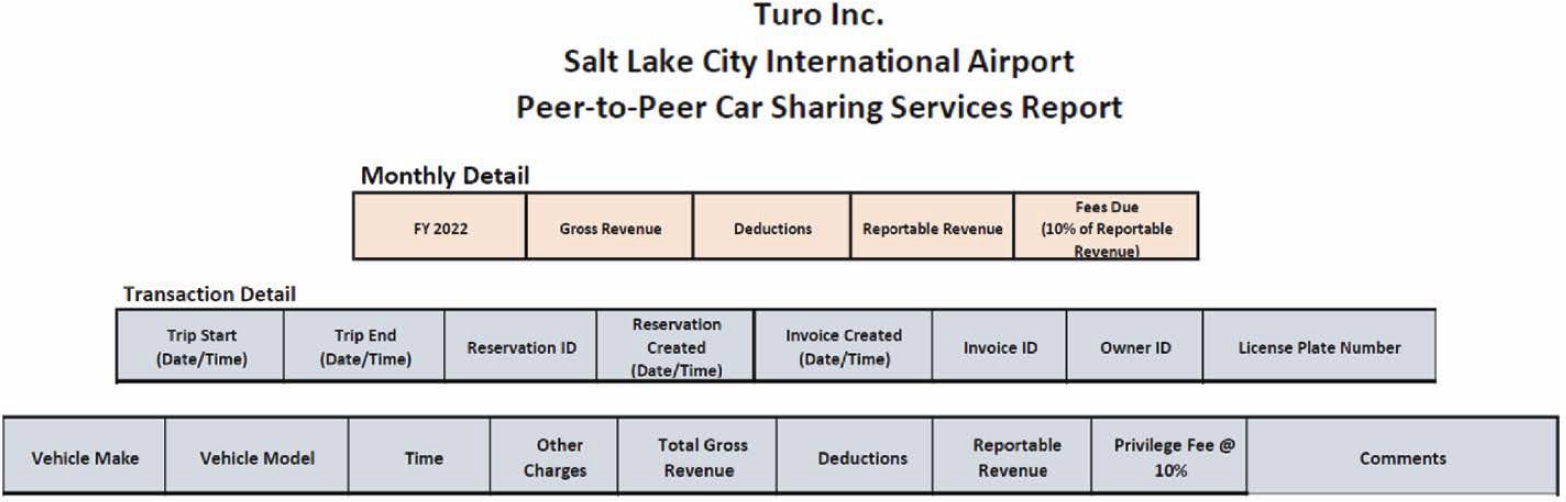

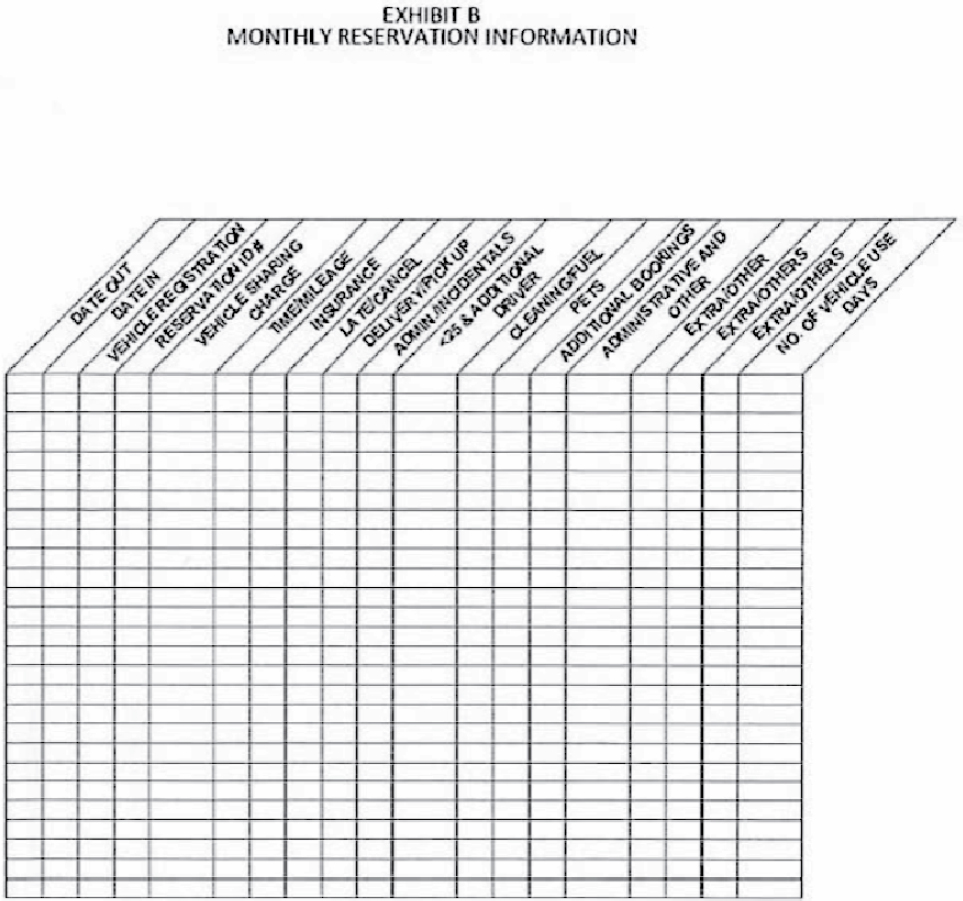

- The company must file a monthly report, signed by an official of the company, indicating airport-related gross receipts, the number of P2P transactions with airport customers, the number of vehicle-use days during the month, and the average P2P carsharing price during this month. Some airports require that on a monthly basis the P2P company report each transaction, including the vehicle license plate number, the make and model, total gross revenue for the transaction, and the privilege fee due.

- The company will work with the airport to implement a technology solution enabling the airport to monitor and audit compliance of the company’s operations if the airport develops or acquires such technology.

An initial comparison of the key requirements contained in the business agreements between airport operators and traditional car rental and P2P carsharing businesses is presented in Table 9-1.

Table 9-1. Comparison of airport business agreements with traditional rental car and P2P carsharing companies.

| Business Agreement Requirement | Type of Rental Car or Carsharing Business | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| On Airport | Off Airport | P2P | |

| Pay a fee calculated as percentage of gross revenues | X | X | X |

| Pay a minimum annual guaranteed amount | X | ||

| Rent airport facilities for customer service and vehicle maintenance | X | ||

| Report monthly revenues | X | X | X |

| Provide service during all hours of scheduled airline operations | X | ||

| Provide ADA-compliant vehicles | X | ||

| Offer car seats/baby seats | X | ||

| Provide for participation in the Airport Concession Disadvantaged Business Enterprise Program | X | ||

| Offer clean, well-maintained vehicles complying with recalls | X | X | X |

| Evaluate safety of owners’ vehicles and check for recalls | X | X | X |

| Have local manager available 24/7 to respond to requests | X | ||

| Train employees/hosts in operating vehicles on airport and complying with rules | X | X | X |

| Inform customers of applicable rules and regulations | X | X | X |

| Limit locations where cars are rented and returned | X | X | X |

| Suspend employees and vehicle owners for violating airport rules, if requested | X | X | X |

| Conduct rental car business only on the airport | X | X | X |

| Apply technology to support monitoring and compliance, if requested | X | X | X |

| Ensure only authorized customers operate vehicles | X | X | X |

Source: InterVISTAS Consulting, November 2022, based on a review of sample airports having business agreements with traditional and P2P carsharing businesses.

As indicated, some requirements that apply to traditional rental car companies (e.g., those related to vehicle fueling and environmental guidelines) do not apply to the P2P carsharing business model.

Online appendices to this report provide examples of business agreements. Chapter 10 presents methods used to audit or confirm a company’s reported revenues and transactions and the supporting technologies.

9.5 Contents of Typical P2P Carsharing Agreements

The following section describes the contents of typical P2P carsharing agreements. It also provides information about the goals and policies of selected airport operators as determined through a review of the agreements and survey described in the online appendices.

Typical Airport Policies and Relevant Goals and Prioritizing Issues and Goals

Given the importance of revenues from parking and ground transportation and rental car businesses, a key policy of all airport sponsors is the maintenance and preservation of such revenues. Just as an airport must address competition from off-airport parking operators and rental car companies, it must address P2P carsharing to ensure that no diminution of airport revenues results from such activities. Additionally, an airport must ensure a fair and reasonable amount is being collected for the use of airport property and access to airline passengers.

Overview of Relevant Business Agreements, Permits, and Leases

As part of the research for this report, examples of the relevant business agreements, permits, and leases with P2P carsharing companies were obtained from representative large, medium, small, and non-hub airports. (Copies of the agreements from the following airports are presented in the online appendices.)

- Denver International Airport (DEN) Peer-to-Peer Carsharing Company Operating Agreement dated June 2022

- Indianapolis International Airport (IND) Airport Use Permit dated January 2022

- Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport (MSP) Peer-to-Peer Carsharing Pilot Agreement dated October 2021

- Ontario International Airport (ONT) Non-Exclusive Operating Agreement Covering Peer-to-Peer Vehicle Sharing, dated September 2022

- Richmond International Airport (RIC) P2P Vehicle-Sharing Concession Agreement dated March 2023

- Salt Lake City International Airport (SLC) Peer-to-Peer Vehicle-Sharing Operating Agreement dated October 2021

- Other Commercial Operator Permit for Peer-to-Peer Vehicle Sharing Coming onto Norman Y. Mineta San Jose International Airport (SJC), dated June 2023

- Sarasota Bradenton International Airport (SRQ) Permit Agreement dated March 2022

- Tallahassee International Airport (TLH) Operating Agreement for Peer-to-Peer Vehicle-Sharing Concession, dated February 2022

- Tampa International Airport (TPA) Use and Permit Agreement for Peer-to-Peer Vehicle-Sharing Concession, dated May 2022

A sample table of contents of a typical P2P carsharing agreement would be as follows:

Introduction

Article 1. Definitions

Article 2. Access to Airport Property

Article 3. Term

Article 4. Payment, Documentation, and Record Requirements

Article 5. Uses and Obligations

Article 6. Indemnification and Insurance

Article 7. Environmental Requirements

Article 8. Miscellaneous Provisions

Each sample article is discussed along with example text from the referenced agreements. However, it is recommended that when developing their own agreement, airport staff determine whether the airport’s recent rental car or other landside concession agreement is a preferable starting point for the P2P agreement and better reflects the unique characteristics of the airport and its policies.

Introduction

The introduction should be similar to other airport agreements. Most airports typically define the tenant in the introduction. An example from the SLC Agreement states the tenant is “Turo Inc., a Delaware corporation authorized to and doing business in Utah, with offices located at 111 Sutter Street, 12th Floor, San Francisco, CA 94104 (‘Operator’).”

A key piece of the introduction is to verify that the P2P operator is authorized to do business in the state. Typically, this can be confirmed by conducting a business search on the appropriate Secretary of State website. Figure 9-1 is a sample from the Secretary of the State of California business search website confirming that Turo is registered in California.

Article 1. Definitions

Several key definitions are found in most P2P carsharing agreements:

-

“Airport Customer.” This definition is necessary to ensure that the fees the P2P operator pays to the airport are collected from everyone picking up vehicles at the airport, whether or not they were an airline passenger. A sample definition from TPA for “Airport Customer” is “any person who makes a Reservation for Peer-to-Peer Vehicle Sharing through Company’s website, mobile application, or other platform for pick up at Airport.” (See TPA Agreement.)

One question that an airport should consider when drafting the definition of “Airport Customer” is whether a P2P company must pay a fee for users who pick up a vehicle at the airport but did not arrive by airplane.

Of the sample agreements, the TPA definition of Airport Customer is the most common and includes everyone who picks up a car at the airport. Other airports have added a time period to the definition. For example, the SLC Agreement defines Airport Customers as “all enplaning, deplaning, or connecting passengers arriving at and/or departing from the Airport within twenty-four (24) hours of taking possession of a Shared Vehicle.” (See SLC Agreement.) The DEN Agreement adds “or returns a Shared Car on Airport Property and leaves by airplane within 24 hours of returning the Shared Car” to catch both pickups and drop-offs occurring at the airport. This is an important definition as it is used in the definition of “Gross Revenues” to follow. The reference to passengers arriving and departing within 24 hours is important: in the past some traditional rental car companies attempted to avoid paying airport fees by stating that passengers’ transactions occurred at a nearby hotel or parking lot and, therefore, the revenues were not airport related.

- “Airport Rules and Regulations.” This definition should be a description of the rules, policies, or regulations promulgated by the airport that are applicable to the P2P operator. These should

-

“Gross Revenues” or “Gross Receipts.” The gross revenues on which the fees are to be paid to the airport by the P2P carsharing operator are a critical piece of the fee calculation. The definition of “Gross Revenues” should be all inclusive. A good starting point for the definition would be the definition of “Gross Revenues” found in an airport’s rental car agreements. For example, “‘Gross Revenues’ includes all sums paid or payable to the P2P carsharing operator, including payments to Shared-Vehicle Owners, for providing Vehicle Sharing services to Airport Customers, and for all ancillary activities allowed under the Operating Agreement.” (See SLC Agreement.)

The only exclusions should be (1) federal, state, or local taxes separately stated on the customer’s agreement for remittance to a taxing authority; (2) insurance proceeds related to damage to the automobile; and (3) tolls and other fines paid by the P2P operator from the customer.

be developed early in the process. (See Step 1 in the section on recommended steps for more guidelines.)

Table 9-2 is a summary of the definitions used in the sample agreement set. The table sets forth items typically included as well as those excluded. The table also notes the airports that use the term “Gross Receipts” instead of “Gross Revenues.”

- “Operator” or some other designation for the P2P Carsharing Company. IND and ONT use the term “Operator,” whereas SRQ uses the term “Permittee.” DEN and TLH use “Turo” or “Company.”

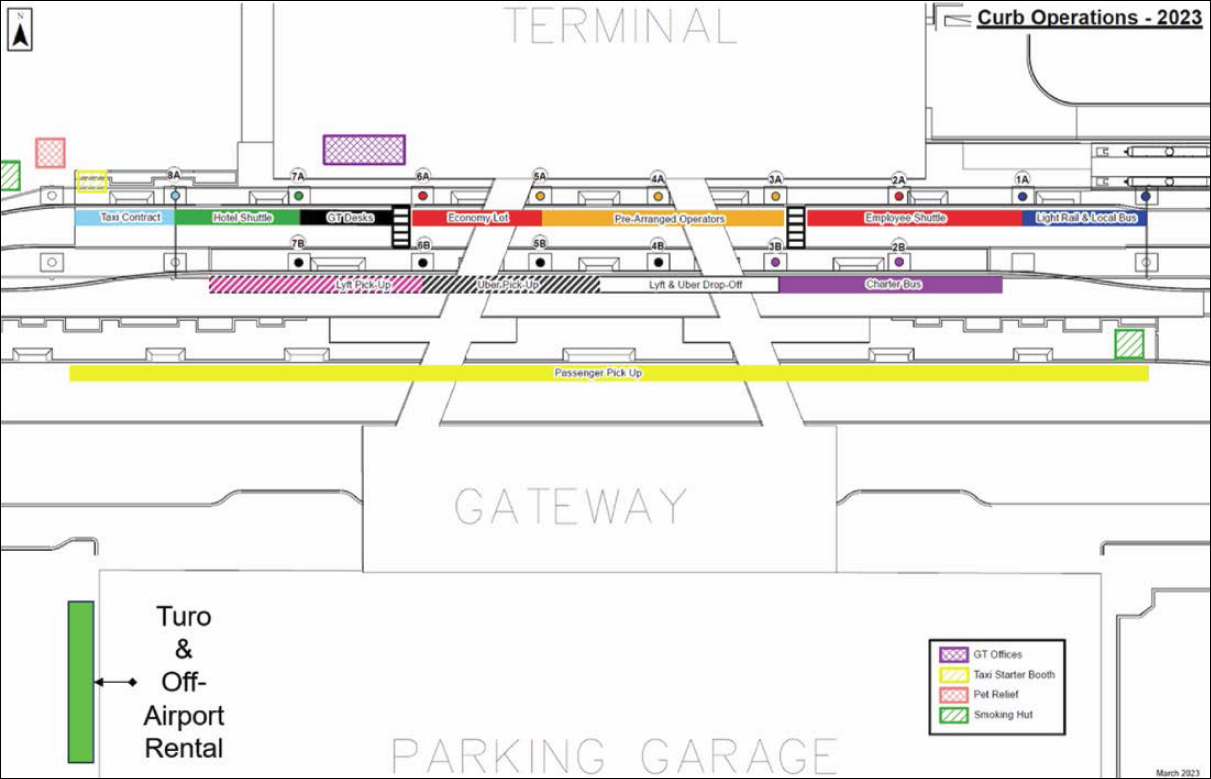

- “Premises” or some other term to refer to the area at the airport to be used by the Operator or Shared-Vehicle Owner. Typically, an exhibit (example shown in Figure 9-2) would be created showing exactly where the exchanges between the Shared-Vehicle Owner and the Airport Customer are permitted.

- “Shared Vehicle” or “Shared Car.” This is another definition necessary to ensure the payment of the correct fees to the airport. It is also necessary in provisions detailing where the transfer of the Shared Vehicle can occur.

- “Shared-Vehicle Owner” or “Shared-Car Owner.” This distinguishes the owner of the shared vehicle from the Operator or Company (e.g., Turo). This is important as the Shared-Vehicle Owner, as well as the Operator or Company, must comply with certain obligations.

- “Vehicle Sharing.” This is the definition of what is actually occurring. For example, the IND Agreement states, “Peer-to-Peer Vehicle Sharing means the authorized use of a Shared Vehicle by a person other than the Shared Vehicle’s Owner as part of a Peer-to-Peer Vehicle Sharing program (such as Operators).” Another definition used in the ONT Agreement clarifies the web-based nature of P2P carsharing: “Peer to Peer Carsharing means an arms-length, remote, web-based, or mobile transaction where a Shared-Vehicle Owner allows a third party to use the Shared Vehicle for a fee.”

Article 2. Access to Airport Property

Just as with other airport agreements, the payment of fees by the P2P operator is in exchange for the right of the P2P operator and the shared-vehicle owners to access the airport. This Article should set forth where the P2P operator may perform the exchange between the Shared-Vehicle Owner and the Airport Customer.

The location can be specific. The MSP Agreement assigns five Shared-Vehicle parking positions on Level 6 of the red parking ramp, as well as a non-exclusive portion of the east side upper-level roadway curbside. The MSP Agreement requires that the Shared-Vehicle Owner remain with the Shared Vehicle until the Airport Customer takes possession and may only park the Vehicle while the Airport Customer is actively loading luggage or while transferring possession of the Shared Vehicle in person. (It is preferable that the exchange be allowed to occur anywhere in a designated parking facility rather than in specific zones or spaces of the parking facility.)

Table 9-2. Examples of definitions used in P2P airport carsharing agreements.

| Hub Size | Non-Hub | Small Hub | |

| Airport | TLH | RIC | SRQ |

| Defined Term | Gross Receipts | Gross Revenues | Gross Revenues |

| Included | |||

| Trip fee time and mileage | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Any income Permittee charges or receives | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Protection plan charges | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Fueling costs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Delivery fee | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Young driver fee or other add-on fees | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Any amount charged by Operator as a pass-through to Shared-Vehicle Driver, such as credits given for out-of-pocket purchases for fuel, oil, or emergency services | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Long-term bookings proceeds | ✓ | ✓ | |

| No deduction for payment of certain taxes levied on Operator’s activities | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Any charges for insurance offered incidental to Shared Car agreement | |||

| Extra additional charges | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Excluded | |||

| Federal, state, or local taxes or surcharges | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Insurance proceeds | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Cancellation fees | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Tickets and other violation charges | ✓ | ||

| Any amounts received from customers then fully passed through to owners, such as post-trip reimbursements and smoking fees | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Certain discounts | |||

| Sale of Operator’s capital assets | |||

| Non-revenue Shared Cars when used by employees of company | |||

| Hub Size | Medium Hub | ||

| Airport | IND | ONT | SJC |

| Defined Term | Gross Receipts | Gross Receipts | Gross Revenues |

| Included | |||

| Trip fee time and mileage | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Any income Permittee charges or receives | ✓ | ||

| Protection plan charges | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Fueling costs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Delivery fee | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Young driver fee or other add-on fees | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Any amount charged by Operator as a pass-through to Shared-Vehicle Driver, such as credits given for out-of-pocket purchases for fuel, oil, or emergency services | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Long-term bookings proceeds | ✓ | ✓ | |

| No deduction for payment of certain taxes levied on Operator’s activities | ✓ | ||

| Any charges for insurance offered incidental to Shared-Car agreement | ✓ | ||

| Extra additional charges | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Excluded | |||

| Federal, state, or local taxes or surcharges | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Insurance proceeds | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Cancellation fees | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Tickets and other violation charges | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Any amounts received from customers then fully passed through to owners, such as post-trip reimbursements and smoking fees | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Certain discounts | |||

| Sale of Operator’s capital assets | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Non-revenue Shared Cars when used by employees of company |

| Hub Size | Large Hub | |||

| Airport | DEN | MSP | TPA | SLC |

| Defined Term | Gross Receipts | Gross Receipts | Gross Receipts | Gross Revenue |

| Included | ||||

| Trip fee time and mileage | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Any income Permittee charges or receives | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Protection plan charges | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Fueling costs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Delivery fee | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Young driver fee or other add-on fees | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Any amount charged by Operator as a pass-through to Shared-Vehicle Driver, such as credits given for out-of-pocket purchases for fuel, oil, or emergency services | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Long-term bookings proceeds | ✓ | |||

| No deduction for payment of certain taxes levied on Operator’s activities | ✓ | |||

| Any charges for insurance offered incidental to the Shared-Car agreement | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Extra additional charges | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Excluded | ||||

| Federal, state, or local taxes or surcharges | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Insurance proceeds | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Cancellation fees | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Tickets and other violation charges | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Any amounts received from customers then fully passed through to owners, such as post-trip reimbursements and smoking fees | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Certain discounts | ✓ | |||

| Sale of Operator’s capital assets | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Non-revenue Shared Cars when used by employees of company | ✓ | |||

Source: DKMG Consulting, LLC, November 2023.

Figure 9-2. Sample exhibit indicating permitted P2P carsharing operation area of airport (bottom left of image).

Article 3. Term

The term of a P2P agreement can vary. The SLC Agreement is month to month, as is the MSP Agreement. The TPA Agreement is for 1 year with two 1-year renewal periods. This is similar to the term of the SRQ Agreement. The IND Agreement is also for 1 year but may be renewed for 1-year terms upon the mutual agreement of IND and Turo. The ONT and TLH Agreements are for a fixed 1-year term. The DEN Agreement has the longest term of the sample set of agreements at 3 years and may be renewed for an additional 1-year period.

Article 4. Payment, Documentation, and Record Requirements

This Article should clearly set forth the calculation of any fees as well as reports and other documentation that the airport will require the P2P operator to submit to provide backup for the fee calculation. This documentation may include the monthly revenues and transactions; the gross fees associated with each transaction; the make, model, and license plate number of each vehicle rented; and the time and date each vehicle was rented and returned to the airport.

The fee is typically 10 percent of the P2P operator’s gross revenues for all vehicle-sharing transactions involving the airport customer. (See Table 9-2 for specific inclusions and exclusions to the definition of gross revenues.) However, there are exceptions. The TPA Agreement is set at 8 percent, whereas the TLH Agreement is set at 6.5 percent, an amount negotiated reflecting the airport’s reluctance to allow vehicle exchanges to occur at the curbside (though other airports

charge 10 percent with no curbside access). When establishing the fees to be charged P2P carsharing businesses, airport staff often consider the fees charged off-airport and on-airport rental car companies.

The agreement should also specify who is responsible for the payment of parking fees if the Shared Vehicles are exchanged in the airport parking garage or lots. In the ONT Agreement, the Airport Customer is responsible for the payment of the parking fees.

As with traditional rental car agreements, the Airport should determine whether a P2P carsharing operator can show the recovery of the fee on its customer invoices. This provision should set forth the name of the fee to be used on the customer invoices, clarify that this fee is not a tax, and require compliance by the P2P operator with all Federal Trade Commission requirements.

This Article may also have a section prohibiting the P2P operator from intentionally diverting carsharing transactions to other locations. The SLC Agreement specifically states that “[the] Operator shall not intentionally divert, through direct or indirect means, any of the Operator’s Vehicle-Sharing transactions or related business with Airport Customers to other locations of Operator or its affiliates without including such transactions in Gross Revenue.”

The fees paid by a P2P operator are typically paid in arrears to an airport, along with a monthly itemized statement of the preceding month’s gross revenues and a cumulative statement of annual gross revenues. For example, the MSP Agreement requires the “Company” to submit a detailed statement showing Gross Receipts for the preceding calendar month. The report must also provide a methodology for identifying P2P carsharing agreements generated at the airport, such as sequentially numbered Carsharing agreements. MSP requires that payment be submitted along with the report, with both due by the 20th day of the following calendar month. The SLC Agreement has a specific form for the reporting included as an exhibit (Figure 9-3) and requires payment be submitted with the form by the 15th day of the month. The TPA Agreement (Figure 9-4) requires additional detail, including vehicle registration. Airport staff indicated that Turo provides vehicle license plate data in lieu of vehicle registration numbers, which is considered acceptable.

The SLC Agreement also requires that the Operator do a true-up within 90 days of the close of the Contract Year. The Operator is required to furnish a written statement prepared in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles and certified by a responsible officer of the Operator specifying the Gross Revenue for the prior year. The Operator must also pay any balance due within a similar time frame.

Some agreements, such as the TPA Agreement, include a security deposit. TPA requires either the posting of a surety bond or an irrevocable letter of credit equal to 3 months’ fees and charges. The SRQ Agreement also requires a 3-month security deposit or $5,000, whichever is greater.

Article 5. Uses and Obligations

This Article will set forth what the P2P carsharing operator can and cannot do at the airport. The P2P operator can typically access the airport only for the operation of a Vehicle-Sharing business and for no other purposes. This Article should also set forth the service standards that the P2P operator must follow. The DEN Agreement sets forth such items as the standard of behavior for Shared-Car Owners and Drivers, prohibits other commercial activities, and prohibits solicitation of customers. It is interesting to note that the solicitation of customers provision specifically excludes use of the mobile application by Owners and Drivers when on airport premises.

Signage is a critical section that should be detailed in this article. This includes signage directing the customer to the appropriate handoff location if the location is somewhere other than a

Figure 9-3. Salt Lake City International Airport Monthly P2P Vehicle-Sharing Services Report exhibit. (Note: Exhibit edited and enlarged for visual clarity; see online appendices for original document.)

Figure 9-4. Tampa International Airport Monthly P2P Vehicle-Sharing Services Report exhibit.

parking lot or garage, as well as whether the P2P carsharing vehicles must contain identifying signage inside the car. The ONT Agreement requires a sign or placard when Owners are conducting hand-to-hand exchanges in the designated areas. No sign or placard is required when the handoff occurs in the parking garage. Identifying signage is useful with regard to enforcement of the obligations set forth in the agreement if handoff occurs at the curbside.

This Article may also contain the typical provision that the P2P operator will comply with all airport security requirements, as well as pay all applicable licenses, permits, and taxes.

Almost all sample agreements include penalties for any violations. Typically, the penalties are as follows:

- First Offense: verbal warning to Shared-Vehicle Owner.

- Second Offense: written warning to Shared-Vehicle Owner and payment of $150 fine.

- Third Offense: suspension from delivering Shared Vehicles to the airport and a $300 fine. Some agreements provide that after the third Offense, the driver will be promptly removed from the P2P carsharing platform.

Examples of the penalty language can be found in the IND, ONT, and SRQ Agreements.

Table 9-3. Examples of the types and amounts of insurance coverage selected airports require of P2P carsharing companies.

| Type | Lowest Limits | Highest Limits |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial General Liability Insurance | $1,000,000 per occurrence and not less than $1,000,000 aggregate | $2,000,000 per occurrence and not less than $2,000,000 aggregate |

| Business Auto Coverage Form | $1,000,000 per occurrence—bodily injury and property damage combined | |

| Workers Compensation | As required by state law | As required by state law |

Source: DKMG Consulting, LLC, August 2023.

Article 6. Indemnification and Insurance

Each airport should include its standard indemnification provision as drafted by legal counsel to ensure compliance with the laws of the state in which the airport is located.

Table 9-3 shows the range of insurance obligations found in the sample P2P agreements. These are only examples, and each airport should consult its risk manager to determine the appropriate types and levels of coverage for its airport.

Article 7. Environmental Requirements

P2P agreements vary as to the environmental requirements contained therein. Environmental requirements relate to P2P carsharing companies’ compliance with the handling of hazardous materials under federal or state laws. This section does not address particular vehicle fuel types. Airport staff should consult with their legal counsel regarding the requirements for the P2P carsharing agreement. These requirements may be similar to the requirements in the airport’s rental car business agreements but will require modification depending on whether the P2P operator leases space at the airport or merely uses a parking lot or garage for vehicle exchanges. For example, RIC simply references “environmental laws” in its list of laws with which an operator must comply, as well as in the indemnity provision. SLC has an entire section on compliance with Environmental Requirements, as well as a stand-alone environmental indemnity provision.

Article 8. Miscellaneous Provisions

This Article should, at a minimum, include the required FAA civil rights and non-discrimination requirements. A more general “Compliance with All Laws” provision is also appropriate, as well as a “Notices” provision.

9.6 Balance Between the Interests of P2P Carsharing Providers and Other Stakeholders

When interacting with airport customers, the primary interests or concerns of airport operators, P2P carsharing companies, traditional rental car companies, and other stakeholders often overlap. Examples of areas in which these stakeholders have similar or overlapping interests are described in the following paragraphs.

Customer Service

Airport operators, P2P carsharing, traditional rental car companies, and other stakeholders seek to provide their airport customers with a high-quality experience. For passengers renting

a car, this includes helping customers to pick up their vehicles quickly and easily and exit the airport (and to rapidly drop off a vehicle upon their return to the airport). Typically, providing customers a high-quality experience includes allowing them to

- Bypass the rental car counters, as can all P2P customers and those traditional rental car customers who frequently rent a car;

- Have a brief walk between the terminal and their waiting (or returned) car or be provided with a courtesy shuttle if the cars are located remotely;

- Easily find their way to their waiting car and out of the airport and when returning to the airport, easily find where to leave the car and how to walk back to the terminal; and

- Enjoy a safe environment (while walking and driving) within airport facilities and roadways.

Operations

P2P carsharing and traditional rental car companies desire sufficient, conveniently located spaces to park vehicles waiting to be leased to arriving customers, where customers can park vehicles upon their return to the airport and where they can store vehicles not in use. P2P carsharing and traditional rental car companies both want their vehicles to be parked and stored securely to deter theft and vandalism. Airport operators, P2P carsharing, and traditional rental car companies want to offer their customers a broad variety of vehicles (e.g., large, medium, and small sedans; SUVs; and vans) using ICEs or electric power.

Business Relations and Space Allocation

P2P carsharing and traditional rental car companies (and other ground transportation providers) are sensitive to any advantages that their competitors may receive from airport operators. Such actual or perceived advantages may be attributable to several differences:

- The fees each company must pay. For example, as discussed in prior sections of this report, airports require traditional rental car companies that have concession contracts (i.e., concessionaires) to pay fees calculated as 10 percent of their airport-related gross receipts for leasing property on the airport, as well as to agree to pay a minimum fee each year [the Minimum Annual Guarantee (MAG)]. Airports do not require off-airport rental car companies (i.e., non-concessionaires) or P2P carsharing companies to lease airport property, pay a MAG, or comply with other requirements imposed upon traditional companies.

- The level of convenience each company is able to offer their customers. Among other factors, airport operators generally consider the revenues received from each class of business (e.g., rental concessionaires) when prioritizing the space or facilities to be assigned to each class of business. Because rental car concessionaires are typically the source of significant revenues and incur greater contractual obligations than non-concessionaire rental car companies or P2P carsharing companies, airport operators generally reserve the more convenient locations for customers of rental car concessionaires and less convenient locations for customers of non-concessionaires and P2P carsharing companies.

-

Use of courtesy shuttles. The courtesy shuttle stop locations assigned to rental car concessionaires are typically more visible and more convenient than those assigned to non-concessionaires. If the customers of a traditional rental car company must ride a shuttle to a remote site, it would be unacceptable for P2P carsharing exchanges to occur at the terminal curbside. It is therefore likely that P2P customers would also be required to use a shuttle or that the vehicle exchange would occur in a designated parking facility.

When a concessionaire’s ready and return spaces are located in a CONRAC, airport operators typically prohibit courtesy shuttle buses serving non-concessionaires from using the terminal curbsides and require that these vehicles use less convenient stops (e.g., the rear of the

- Counter locations. The location of the ready and return spaces and rental car counters leased by rental car concessionaires are typically more convenient (and more visible) than the spaces assigned to P2P carsharing companies for vehicle pickup and drop-off. This helps ensure that rental car concessionaires’ customers need not walk past the customer pickup areas assigned to P2P carsharing companies.

CONRAC). This is done to ensure that, compared with the concessionaire companies, the non-concessionaire companies do not receive a competitive advantage, even if these customers are required to be double-bused.

Airport operators frequently consider other factors when allocating terminal building passenger drop-off and pickup areas at the terminal building curbside or other locations. These factors—which may not be relevant to the allocation of space to rental car concessionaires, non-concessionaires, or P2P carsharing companies—include (1) customer expectations (e.g., location of taxicab- and limousine-boarding areas are typically near baggage claim areas), (2) space required for vehicle operations (e.g., to maneuver into and out of curbside spaces, full-size charter buses require more space than small sedans or vans), and (3) desire to promote use of public buses and other efficient travel modes (e.g., public transit is allocated the most convenient drop-off and pickup spaces at several airports).

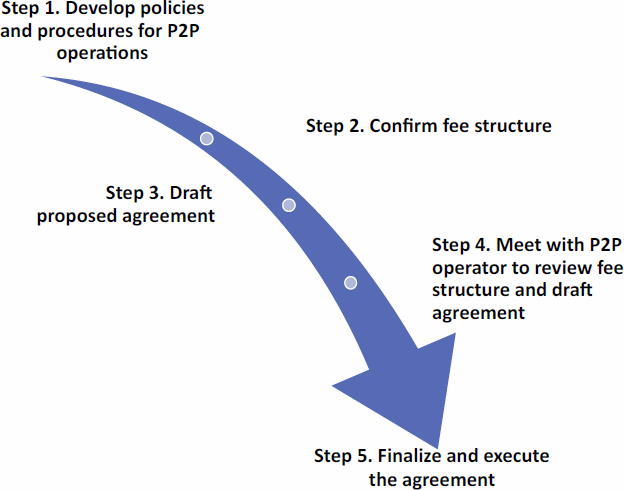

9.7 Recommended Steps to Develop Policies and Negotiate Agreements

As with any airport agreement, the more preparation and diligence airport staff conduct in advance of negotiations with the P2P carsharing operator, the better the resulting agreement. A starting point should be the on-airport rental car agreement, provided this agreement is relatively current. A review of the contents of this agreement will provide an outline of the provisions that will be relevant to an agreement with a P2P carsharing operator.

A typical process is set forth in Figure 9-5.

Figure 9-5. Process to develop an agreement between a P2P carsharing company and an airport operator.

Step 1 is the development of policies and procedures for P2P carsharing operations. This primarily involves a determination of where the vehicle exchange will take place.

- Will the exchange take place on the curb front or in a specific parking garage or parking lot? An exhibit detailing the exact location should then be developed for inclusion in the agreement.

- Should the P2P vehicle be identified with a placard? (For the reasons described in Chapter 10, it is recommended that placards not be required if the exchange is to occur in an airport parking facility.)

- Will there be any restrictions on the type of vehicle? For example, the IND Agreement excludes P2P carsharing businesses from offering certain vehicles (e.g., ¾-ton trucks, passenger vans for 15 people, cargo vans, commercial vehicles, and trucks with dual rear wheels).

Step 2 is confirming the fee structure:

- What percentage of gross receipts will be imposed on the P2P carsharing business?

- What will be included in the definition of gross receipts?

- What will be excluded from the definition of gross receipts?

- When will payment be due?

- What will be the year-end audit requirements?

- Will there be a security deposit requirement?

Step 3 is to draft the agreement.

The sample agreements provided in the online appendices are useful tools in drafting a new P2P agreement. The MSP, SLC, TLH, and TPA agreements have tables of contents that could be useful in determining what types of provisions should be included in the draft agreement. Another useful resource might be an airport’s existing rental car agreement or other landside concession agreement, which would ensure that specific provisions to the airport are included in the new P2P agreement. The policies and procedures developed in Step 1 should all be included in the draft agreement, as well as the fee structure determined in Step 2. It is suggested that the agreement require the P2P carsharing business to provide, for each transaction, the revenue amount, the date and time of transaction, and the make, model, and license plate number of the vehicle.

Step 4 is to schedule meetings with the P2P carsharing business (and, subsequently, with internal stakeholders) to review the proposed fee structure and draft agreement.

As with any agreement, it is likely that the operator will have questions or comments on the draft agreement. However, if the P2P carsharing company wants to access the airport, the company will understand that an agreement is necessary.

Given that many different divisions of an airport may have responsibilities under the new P2P agreement, it might be useful to hold an internal stakeholder meeting to review the terms of the agreement and specifically assign roles and responsibilities to ensure that the provisions of the agreement are enforced.

Step 5 is to finalize the agreement and execute the document.

The post-agreement steps—that is, the enforcement of the provisions in the agreement—may be the most difficult. Every airport should determine which division will be responsible for monitoring the compliance of the P2P carsharing company with the terms and conditions of the agreement and who will be responsible for assessing violation notices and fines. The hope is that the agreement will sit on a shelf or in a file cabinet for the term of the agreement, but it is good to be proactive and ensure that airport staff are aware of the new agreement and the specific enforcement tools contained therein.