Exploring Airport Employee Commuting and Transportation Needs (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

For many U.S. workers, their workday begins and ends with an automobile commute along roads filled with potholes and traffic (Leonard, 2001, p. 27).

Airports may be one of the largest employers in their state. For example, Denver International Airport is the largest employer in the state of Colorado, with a total of40,000 employees; Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport is the largest employer in the state of Georgia, with a total of 63,000 employees; Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport employs approximately 60,000 in total; and Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) employs 57,000 in total.

These employees may work at an airport campus that spans thousands of acres. Denver International Airport, for example, consists of 33,531 acres; Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport consists of4,700 acres; Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport consists of 17,207 acres; and LAX consists of 3,500 acres.

These large airport campuses that employ thousands of employees have confronted numerous challenges associated with their growth, including the ground access challenge. Although airport operators commonly place a high priority on passenger transportation needs (often due to the revenues this generates), the transportation needs of employees who work at the airport on a daily basis also deserve consideration.

For the purposes of this synthesis, airports are managed by an airport operator. The airport operator may be in the form of an airport authority, port authority, state, city, county, or multi-jurisdictional agency. These airport operators employ personnel working directly for the airport, in areas such as finance, maintenance, marketing, and operations. Other employees at the airport are employed by various airport tenants. Airport tenants may include airlines, food and beverage concessionaires, retail concessionaires, rental car concessionaires, ground handlers, and federal agencies such as the FAA and the TSA. These airport tenants employ personnel directly working for tenant companies, in varied areas such as retail, food and beverage, rental cars, ground handling, aircraft fueling, passenger screening, and air traffic control.

Although the airport operator typically employs a significant number of employees to keep the airport operating safely, “In the United States, the airport operator typically employs less than 10% of the [total] airport employee population” (Ricard, 2012, p. 53). Employees of both the airport operator and airport tenants are the focus of this synthesis. These airport employees must commute to and from the airport each day. Although employees may choose to commute via driving alone [also referred to as a single occupant vehicle (SOV)], other modes include carpooling, being dropped off, public transit bus, public transit light rail, bicycle, motorcycle, scooter, skateboard, walking, wheelchair, ride-hailing app, taxi, vanpool, or employee shuttle. For some employees, the commute consists of multiple modes. For instance, an employee may ride a bike from their residence to the bus stop, take the bus for a certain distance, and then ride their bike from the bus stop to their specific work site at the airport. Employees may also utilize a

park-and-ride facility, whereby they drive in an SOV to the train station, park their car, and then ride the train to work at the airport. In sum, the first and last mile of an employee’s commute may include multiple modes, creating unique challenges for employees.

Additionally, an employee may have two commutes to get to work at the airport. Once the first commute is completed, the second commute begins. For instance, once an employee finishes their primary commute (signified by parking their vehicle, or exiting the bus or train), the employee may then board an employee shuttle to be transported to their specific work site at the airport. This second commute adds to the duration of the commute and must be considered by employees as part of their overall commute strategy.

At San Francisco International Airport, approximately 60% of airport employees work within the terminal complex. However, approximately 40% work off-site, requiring a second commute. For example, once an employee arrives at the airport, via rail or vehicle, for instance, the employee must engage with additional transportation to transit to their specific work site. Fortunately, approximately half of those working off-site have access to the airport’s AirTrain, which “provides year-round service 24 hours a day, with station departures as frequent as every four minutes.” The AirTrain Red Line “connects all terminals, terminal garages, the BART Station and the Grand Hyatt at SFO.” The Blue Line “connects Long-Term Parking, the Rental Car Center, all terminals, terminal garages, the BART Station and the Grand Hyatt at SFO” (SFO, n.d.). Even so, this second commute adds to the duration of an employee’s daily commute.

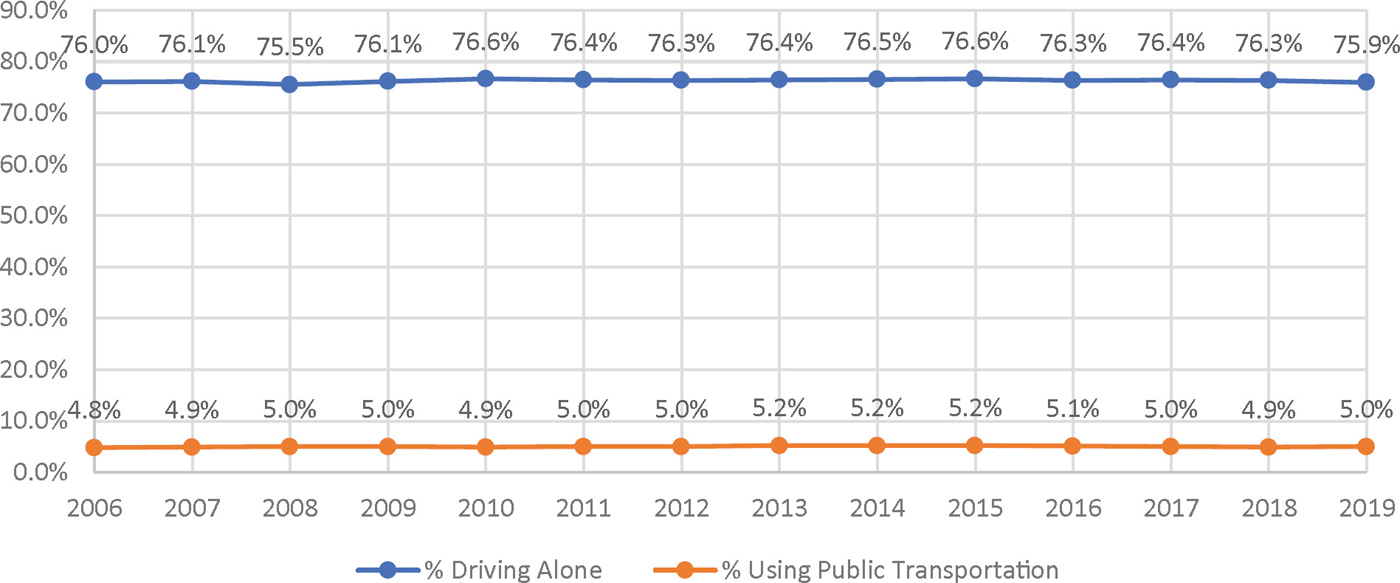

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the majority of U.S. workers throughout the economy commute to work by driving alone in an SOV. In fact, as presented in Figure 1, more than 70% of U.S. workers typically drive alone to work. SOVs represent a major source of vehicular trips, many of which are the source of employees driving to and from work.

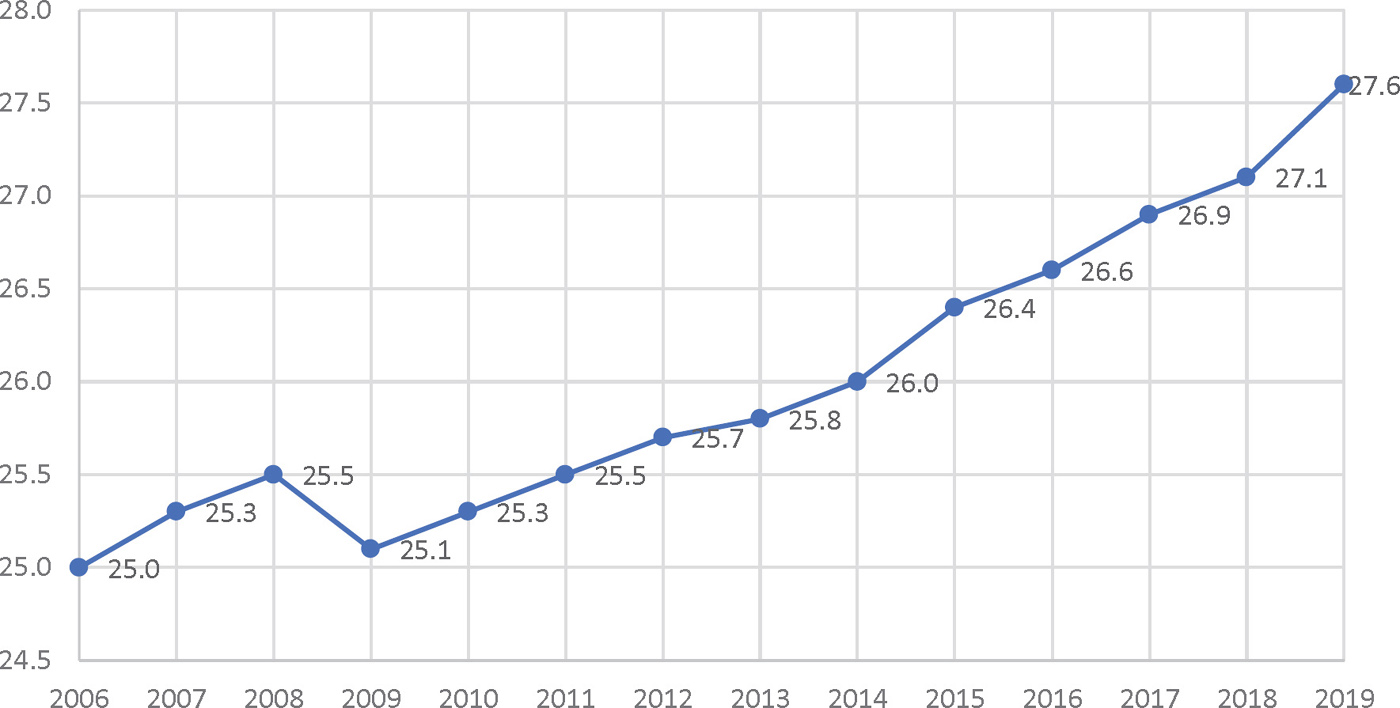

Additionally, workers throughout the country are driving longer distances to commute to work. As presented in Figure 2, mean (average) travel time to work for employees in all segments of the economy has gradually increased since 2009, partly driven by an increase in housing in the suburbs, farther away from city centers (and airports). Emre and De Spiegeleare discovered that “[in general], on average, [among all employees throughout the economy], commuting takes up about 38 minutes of a person’s day” (2021, p. 2444).

Rather than having shorter commutes, “Airport employees have longer commutes than most other commuters in their respective cities” (Zimny-Schmitt and Sperling, 2020, para. 10). This is often due to the distance an airport may be from residential areas. For example, Denver International Airport was developed on a site 25 miles northeast of downtown Denver. This site was chosen for its distance from residential areas (thus minimizing noise impacts), the ability to accommodate a runway layout that is not compromised by Colorado’s winter blizzards, and the flexibility to allow for future expansions. However, this location has created a commute much longer than was required to reach the site of the former Denver Stapleton Airport, which was approximately seven miles from downtown Denver.

Longer commutes are not without costs. Emre and De Spiegeleare (2001) found that longer commutes are related to lower commitment and lower perceived well-being. Ma and Ye (2019) discovered that “the long commute will not only place physical and mental burden on workers, but also directly influence their work participation and engagement, leading to a direct loss of productivity in the workplace” (p. 139).

Longer commutes, as well as a lack of access to transportation, can negatively impact employee recruitment and retention. A number of U.S. companies have found that commute time impacts staff engagement and retention. One researcher found that “The likelihood of quitting the job increased to over 92% for employees with a commute time of 30 to 45 minutes” (Paul, 2022, para. 7). According to Sullivan (2015, para. 13), impacts to recruiting may appear in the following ways:

- Reduced number of applicants. Current and former employees who complain about their commute to work may discourage future applicants.

- Offers rejected. More job offers will be rejected if affected applicants see that major commuting issues are not mitigated by the firm.

- Reduced employee health. Research has shown that prolonged sitting and less time for exercise as a result of long commutes can lead to less physical activity, excess belly fat, and higher blood pressure. These issues can also increase the medical costs to a firm.

- Less free income to spend. The high costs of commuting will reduce an employee’s discretionary income, which essentially makes jobs appear to pay less, reducing market competitiveness.

The higher costs of commuting, in particular, can have significant impacts on employees. The average employee in the United States spends $8,466 and 239 hours commuting on an annual basis. That’s 31% more money and 20% more time than before the pandemic. It is estimated that 19% of an employee’s income is spent on commuting to and from work. This includes an average of $867 on fuel (or likely less electricity charging costs for an electric vehicle) and $410 on maintenance a year for a fuel-powered vehicle.

Additional costs created by commuting can generally only be absorbed by higher wages. “Rising fuel costs have led to increased costs for commuting across the board, creating an impact on household budgets” (“The Impact of Commuting on Employees,” 2008, para. 5). French et al. (2020) discovered that “10 additional minutes of commuting time one-way [required] … [a] $1,172 increase in annual income or a $0.33 increase in hourly wage” to recoup higher costs associated with commuting (p. 5289).

Commuting can also create negative environmental impacts, related to vehicle miles traveled, roadway congestion, and resulting emissions. This has caused companies to consider how to minimize these environmental impacts. “Over the last decade, many companies have made the conscious decision to implement sustainability plans to improve the triple bottom line: economic, social, and environmental performance” (Sattler and Davis, 2014, p. 32). “The triple bottom line is a business concept that requires firms to commit to measuring their social and environmental impacts—in addition to their financial performance—rather than solely focusing on generating profit, or the standard bottom line” (Sattler and Davis, 2014, p. 32). With an obligation to the community to ensure that the triple bottom line is adequately addressed, many airports are considering how to influence employee commuting behavior and provide alternatives that both meet employee needs and contribute to an enhanced triple bottom line (Zimny-Schmitt and Sperling, 2020).

Influencing employee commuting behavior requires a consideration of the specific commuting challenges experienced by employees, as well as employee transportation needs and airport sustainability goals related to vehicle emissions, roadway congestion, and community goodwill. Some airports are attempting to influence employee commuting behavior with various programs, including incentives and disincentives. Depending on the extent of these programs and the resulting success, an airport may be ranked as a “Best Workplace for Commuters” by the University of South Florida’s Center for Urban Transportation Research. This ranking may assist with employer recruitment and retention, especially for employees and candidates who prioritize commuting concerns.

Synthesis Overview

This synthesis describes how airport employees commute to and from work, and how airports are seeking to influence employee transportation decisions. Challenges experienced by airport employees commuting to and from work are also explored and include the mode of transportation used and reasons for choosing a specific mode. The report is also forward-looking with an emphasis on methods airports can use to meet employee transportation needs and influence their behavior toward alternative transportation modes. The audience for this report is airport management and staff seeking to understand, plan for, and accommodate the transportation commuting needs of airport employees.

The remaining chapters of the report will provide the reader with in-depth knowledge of the issues surrounding employee commuting, including those challenges and benefits specific to airports.

Chapter 2: Synthesis Methodology presents the methodology used in the project. Topics include recipients/participants, data collection instruments, survey and interview methodology, and data analysis techniques.

Chapter 3: Literature Review presents findings obtained from a thorough review of the literature, aiding the reader in more deeply understanding this issue, including relevant research. Topics include ground access, environmental sustainability, transportation demand management, transportation management associations/organizations, employee commute options (ECO) programs, disadvantages of commuting, balance of utility, benefits of commuting, active commuting, efforts to influence employee commuting behavior, incentives and disincentives, employee recruitment and retention, and challenges in providing commuting options.

Chapter 4: Survey Results presents the findings from a survey of employees at airports. Topics addressed include transportation methods, duration of commute, length of commute in miles, second commute, reasons for choosing a certain commuting method, degree of joy during the commute, health impacts, work-life balance, and employer-provided transportation benefits.

Chapter 5: Case Examples presents eight case examples highlighting methods by airports used to alter employee commuting behavior.

Chapter 6: Summary of Findings provides a summary of key findings of the synthesis, as well as comments on the state of research and recommendations for future research related to this topic.

The following appendices can be found at the end of this synthesis: