Design Options to Reduce Conflicts Between Turning Motor Vehicles and Bicycles: Conduct of Research Report (2024)

Chapter: 5 Overview of Research Methods and Site Selection

CHAPTER 5

Overview of Research Methods and Site Selection

Overview of Research Methods

Three research approaches were used to explore the safety performance of intersection treatment types for bicycles at intersections: 1) crash analysis; 2) video-based conflict analysis; and 3) human factors study (simulation). Each method has its relative strengths and disadvantages, summarized in Table 13, and described below.

Table 13. Research Methods Deployed: Strengths and Disadvantages

| Method | Scale | Strengths | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-Crash Analysis | 573 sites 233 crashes |

|

|

| Video-based Conflict Analysis | 28 sites 2,167 hours of video 16,107 conflicts |

|

|

| Human Factors Study (Simulator) | 40 participants 640 turns 28,800 secs data |

|

|

Micro-Crash Analysis

Crashes are the most direct and measurable safety outcome, but all crash data analysis is retrospective and depends on the accuracy and quality of reported crash data. Bicycle crash analysis is particularly challenging because these crashes are very rare events and sufficient samples are not easily obtained for statistical analysis. Researchers do not typically know the precise details of crash-level actions and events, relying instead on coded fields in the reported crash data. Importantly, exposure data, both of bicycles and vehicles, is needed to allow comparison of counts but is often not available or only available at limited frequency and for short duration (e.g., for single day of the month). Lastly, because not all persons will

choose to bicycle on all facilities, there is a potential for omitted bias in the crash data. In other words, less experienced or risk adverse bicyclists may avoid higher speed roadways while a wider array of people may choose to bicycle on lower speed facilities, and this bias may impact safety analysis results in ways that are difficult to measure.

Video-Based Conflict Analysis

Conflicts, or interactions between vehicles, occur much more frequently than crashes. Using automated video-based conflict analysis gathers robust detail about each bicycle-motor vehicle interaction including speeds, trajectories and information about all vehicles’ paths. There is a reasonable body of research that correlates conflicts and other surrogate measures of safety with actual crashes (i.e., that observing conflicts is useful in understanding the actual reported crash performance). The research, however, is less developed for bicycle-motor vehicle crashes. It also is reasonable to assume that fewer conflicts would be associated with higher levels of comfort for road users, including people on bikes, and it is useful to know the rate and severity of conflicts, though this has not yet been validated by research. Lastly, the comment on omitted bias also applies to the conflict analysis.

Human Factors Study (Simulator)

Both the crash and video-based conflict studies are observational –what has been designed and built and how existing traffic and drivers use the roadway can only be observed. In the driving simulator, the experimental environment can be completely controlled and the variation in outcome is in the driver’s performance within the same situation. In addition, significant and detailed information about each driver’s performance can be collected, however, there is a limitation on the number of people that can be included in the experiment (typical experimental cohorts are between 30 and 40 people. While many measures have been validated to real world conditions and is directly related to safety (e.g., driver speed selection), not all data maps directly to safety outcomes.

Site Selection

This section describes the process used to select sites (i.e., intersection approaches) for the micro crash analysis and video-based conflict analysis. The selection process for the micro crash analysis involved consolidating data from several sources (data provided by cities, readily available data from Open Streets Map and detailed desktop data collected via Google Street View). The sites selected for the conflict analysis are a subset of the sites for the micro analysis. Sites were selected from four cities:

- Austin, TX

- Minneapolis, MN

- New York City, NY

- Seattle, WA

Intersection treatment Types

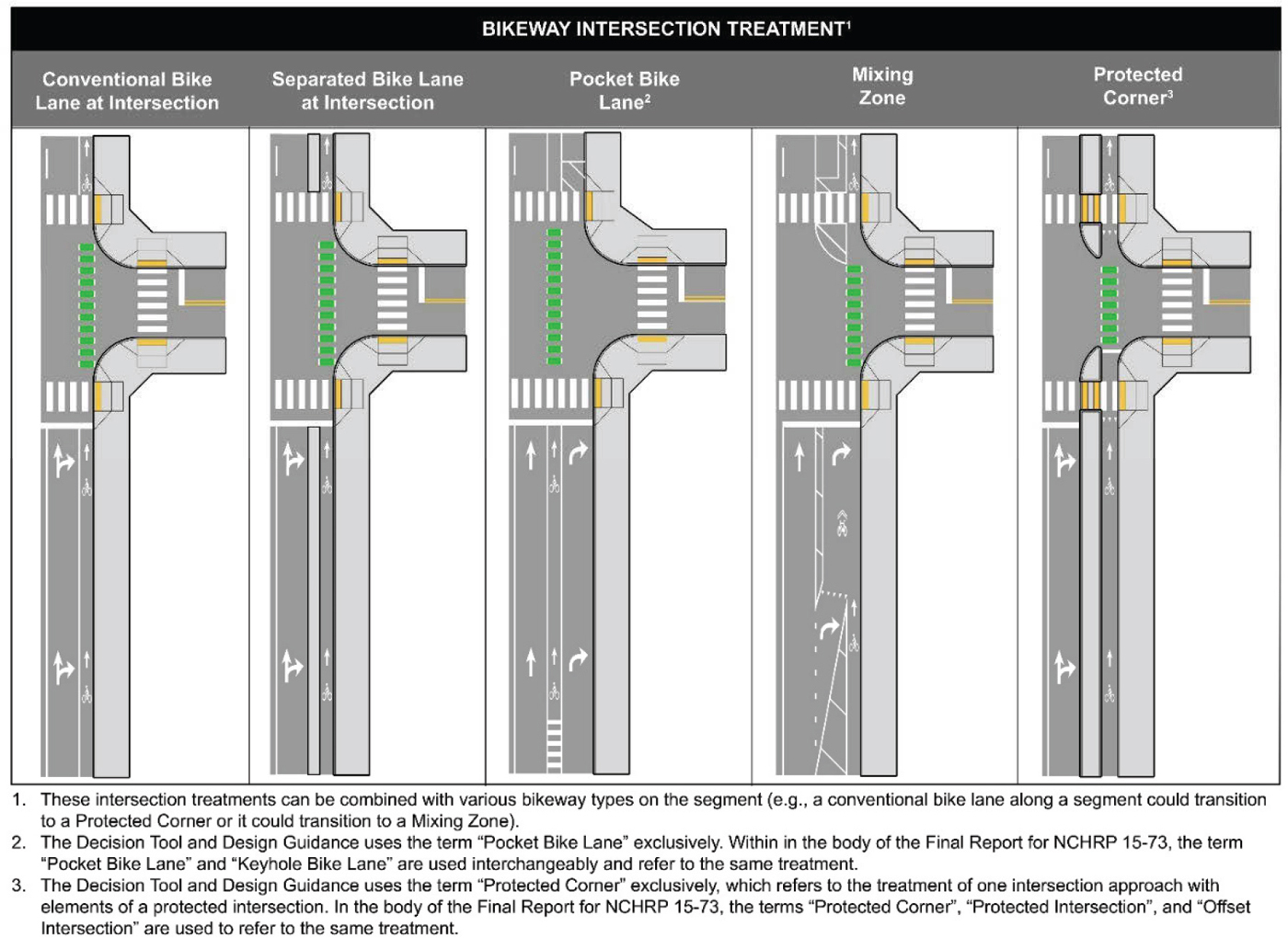

Based on the results of State of the Practice review, the site selection focused on five different intersection treatment types. Each of the treatments is listed below with a definition. Definitions for these treatments have been sourced primarily from the FHWA Separated Bike Lane Planning and Design Guide (FHWA 2015) and the upcoming AASHTO Bike Guide (AASHTO, forthcoming).

Conventional Bike Lane

A conventional bike lane design maintains the bikeway between the curb and motor vehicle lane in advance of the intersection to the stop bar. As a result, no mixing of motor vehicles and bicyclists is required in advance of the intersection.

Separated Bike Lane

Separated bike lane designs maintain the bikeway, with some type of physical vertical separation, between the curb and motor vehicle lane in advance of the intersection to the stop bar. Signalization may be used to give priority to the movement of either the bicyclists or motorists.

Pocket/Keyhole Bike Lane

Pocket or keyhole bike lane designs move cyclists to the left of the motor vehicle right turn lane in advance of the intersection before vehicles can move right. This design places the responsibility for yielding clearly on drivers turning right and brings bicyclists into a highly visible position. In the lateral shift configuration, potential conflicts between right-turning vehicles and through bicyclists occur before the intersection.

Mixing Zone

The mixing zone design is an intersection treatment where bicyclists and right-turning automobiles merge into one travel lane approaching the intersection. Mixing zones provide a design option in which the potential conflict between right-turning vehicles and through bicyclists occurs before the intersection, similar to the lateral shift.

Protected Intersection

The protected intersection uses physical separation and specific design elements to increase the predictability and clarity of right of way assignment for motorists and bicyclists. Pedestrian and bicyclist operating spaces are clearly delineated within the intersection to minimize potential conflicts between users. Elements of a protected intersection include: corner island, motorist yield zone, pedestrian refuge median, pedestrian crossing of the separated bike lane, pedestrian curb ramp, bicycle crossing of travel lanes, pedestrian crossing of travel lanes, and may include a forward bicycle queuing area. A bend out intersection design also has similar features to a protected intersection. Figure 4 shows the plan view of these treatment types.

Identifying Sites (Intersections)

For the cities of Seattle, Austin, Minneapolis and New York, the team submitted data requests (e.g., crash data, speed data, AADT) and combined this data with readily available data from Open Streets Map. An initial universe of potential sites (intersections) was created by selecting intersections which met the criteria: presence of a bikeway and presence of a traffic signal. In an effort to focus our initial desktop data collection efforts, this initial universe of potential of sites focused on intersections with Open Street Maps functional classes in the following combinations:

- Primary streets Only,

- Primary + Secondary streets, and

- Secondary streets Only.

After completion of the macro crash analysis (see page 64), the team learned that the majority of crashes in all three states (i.e., CA, MN, TX) are occurring at intersections where a street classified as Primary or Secondary intersects with a Tertiary or Local Street. Based on these findings, the team decided to expand the universe of sites to include 30 additional locations at intersections with Primary + Tertiary and Secondary + Tertiary intersections.

Desktop Data Collection

The team completed a desktop data collection of candidate intersections to gather information via Google Maps / Street View that was unavailable via data requests from case cities (e.g., number of lanes, bicycle

treatment, presence of bicycle signal). Starting with this output from candidate intersection locations, the project team manually conducted a desktop audit of sites to identify individual bicycle approaches, remove locations that do not have appropriate designs for the study and to collect information on key design and contextual data for each approach. The following factors were considered:

- Each bicycle approach that matched one of the design types was recorded as a candidate approach.

- If an intersection had no bikeway facilities on any approach it was removed.

- Candidate approaches might be excluded for other reasons, including if the approach bikeway for the bicycle is a shared lane (i.e., not a bike lane or separated bike lane), or a two-way separated bikeway.

In addition to the intersection design type, other information collected in the desktop audit included information on the intersection characteristics, such as the number of legs and angle of approach. Most information was specific to each approach (and progression through the intersection), including:

- The approach direction

- Presence of bike lane markings through the intersection

- Type of bikeway on approach

- Presence of a bus stops

- Bike signal

- Opposing left turns lanes (and their signal type)

Data was also collected on the number and types of lanes on approach, and the number and direction of lanes on the cross street. Finally, information using the time capsule feature on Street View to identify the month and year of the earliest captured Street View with the current facility layout, and the month and year of the latest captured Street View with the prior layout were also collected. Each intersection and approach received a unique identifier. Each approach was geo-coded to a specific OSM segment. Data collected in the desktop audit are shown in Appendix C.

Refinements and Exclusions

Once the initial desktop data collection was complete, the entire list of sites was reviewed more closely. The objective was to develop a list of candidate sites for the micro-crash and conflict analysis that did not have unusual features that would confound the safety analysis. Thus, intersections with the following criteria were excluded:

- With five or more legs

- Locations with channelized turn lanes

- Approaches that cross nine or more lanes

- Locations where the current design was implemented January 2019 or later were excluded because of the unavailability of after crash data at the time data were collected

Locations with large skews were generally excluded for the conventional bike lane and pocket bike lane locations due to the availability of sufficient non-skew locations for these intersection treatment types. Given a relatively small sample size for mixing zones, separated bike lanes and offset / protected locations, the team reviewed locations that were skewed and determined, that there were few that could be retained. Finally, filters were created to more easily identify the following characteristics:

- Offset / protected intersections were coded based on whether they had at least 6 feet of offset or not.

- Mixing zones were coded to indicate whether they had full mixing zone markings (turn arrow, bike stencil markings and / or shared turn lane signage) and were distinguished from those where the mixing zone markings was not explicit.

- Pocket lane designs were coded to distinguish between those wherein the turn lane was wide enough to fully fit a motor vehicle and in which roadway markings indicate that bikes should cross over prior to the turn lane rather than designs that were not explicit.

- Bike lanes were coded to note which bike lane approaches were curb tight and which were not curb tight (e.g., parking or other use to the right of the right-side bike lane).

The data collected via Google Street View was spatially joined to additional contextual data provided from case cities and Open Streets Maps. This included: AADT, bike volume measurements, installation date and speed limits. The number of sites per intersection treatment type that were excluded and those that were retained are shown in Table 14. The sites that are listed as remaining will be included in the micro crash analysis.

Table 14. Count of Sites by Treatment Type and City Identified, Excluded and Retained

| Approaches retained and excluded by design type | Austin | Minneapolis | New York | Seattle | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Bike Lane | |||||

| Total identified | 131 | 169 | 155 | 66 | 521 |

| Sites excluded | 33 | 29 | 48 | 23 | 133 |

| Sites remaining | 98 | 140 | 107 | 43 | 388 |

| Separated Bike Lane | |||||

| Total identified | 21 | 34 | 19 | 42 | 116 |

| Sites excluded | 16 | 12 | 9 | 25 | 62 |

| Sites remaining | 5 | 22 | 10 | 17 | 54 |

| Pocket or Keyhole Bike Lane | |||||

| Total identified | 46 | 26 | 8 | 20 | 100 |

| Sites excluded | 18 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 34 |

| Sites remaining | 28 | 22 | 5 | 11 | 66 |

| Mixing Zone | |||||

| Total identified | 21 | 8 | 29 | 16 | 74 |

| Sites excluded | 12 | 3 | 5 | 11 | 31 |

| Sites remaining | 9 | 5 | 24 | 5 | 43 |

| Offset/Protected* | |||||

| Total identified | 18 | 19 | 5 | 42 | |

| Sites excluded | 14 | 13 | 5 | 32 | |

| Sites remaining | 4 | 6* | 10 | ||

| Overall | |||||

| Total identified | 237 | 237 | 230 | 149 | 853 |

| Sites excluded | 93 | 48 | 78 | 73 | 292 |

| Sites remaining | 144 | 189 | 152 | 76 | 561 |

Note *During the conflict analysis site selection process, additional offset / protected locations were added in New York. The six sites listed here include three from the initial data set and three additional from the conflict analysis site selection process.