Design Options to Reduce Conflicts Between Turning Motor Vehicles and Bicycles: Conduct of Research Report (2024)

Chapter: Appendix D: Macro Crash Analysis

Appendix D

Macro Crash Analysis

Introduction

This memorandum provides a summary of a macro crash analysis conducted to understand broad crash patterns related to bicycle-motor vehicle crashes at signalized intersections using state-level data, with a focus on crashes involving turning vehicles. This descriptive crash analysis consists of tabulations on key variables (land use, functional classification, crash type) of interest to identify attributes that are linked to crashes and crash severity in three case-study states: California, Minnesota, and Texas.

This memorandum is submitted as an attachment to the Quarterly Progress Report for October through December of 2021 to provide the panel an update on analysis progress between panel meetings and other technical memorandum submittals. The broad patterns summarized here will then inform the subsequent, more detailed analysis with additional contextual data for specific sites in our study cities (Austin, Minneapolis, New York City, and Seattle). The team anticipates providing the panel an update on the micro analysis in the form of a similar summary memo attached to the Quarterly Progress Report for January through March of 2022 to be submitted in early April.

Analysis Methodology

This section describes the steps taken to assemble the working datasets, as well as the analytical framework used to develop the summary statistics. Following sections present the descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) of crashes stratified by various attributes (e.g. crash severity, functional class).

The analyses reported here do not adjust for exposure rates, so results should be interpreted carefully to understand why certain patterns may emerge. For example, in many communities, pedestrian and bicyclist crashes are more common during daylight conditions than dark conditions. This does not mean that daylight conditions are more dangerous than dark conditions; rather, it reflects the fact that people are more likely to travel, and especially more likely to travel by walking or bicycling, in light conditions than in dark conditions. Looking at relative crash severity within a category can help the reader understand these dynamics. In the aforementioned daylight/dark example, the percentage of crashes under each lighting condition that are severe versus non-severe provides a better indicator of how the environmental condition impacts safety than relative frequency of occurrence. In these analyses, not accounting for exposure may result in relatively fewer crashes being observed at large, busy intersections without dedicated bicycle facilities – not because they are safer or serve bicyclists better, but because they feel so unsafe that bicyclists avoid them. Cross-sectional, crosstab analysis like this should not be used to infer causality.

State Selection

As stated in the site selection memo submitted to the panel (June 2021), the macro crash analysis is intended to represent patterns across several states for which crash data are readily available, with as much overlap with our micro crash analysis cities as practical. The team had originally planned on using readily available data from the states where the municipalities selected for the micro analysis are located (i.e. Austin, TX; Minneapolis, MN; New York, NY; Seattle, WA), plus other states known to have reliable data. However, based on data availability and project budget constraints, the team decided to use a “case study” approach to limit the risks and limitations of consolidating data across multiple data sets. Each state has

different strengths and weaknesses in their data. Pooling data across states would result in the “lowest common denominator” of data and we would lose nuance and information. For example, California, Minnesota, and Texas all report different levels and types of information about the bicyclist’s movements and actions preceding a bicycle-motor vehicle crash, with California providing the most detailed information and Texas providing virtually none. If we pooled data across all three states, we would not be able to analyze the California-specific bicyclist movement and action fields. By looking at the three states separately in a case study format, we can leverage the strengths of each dataset to understand bicyclist safety considerations at signalized intersections and still allow for geographic diversity and nuance.

Crash Data

This analysis used geocoded crash data and the geo-location of each crash record is critically important, as it enables us to spatially join roadway, land use, signalization, and street functional classification to the crash records. These contextual datasets can provide better understanding of the systemic risk factors for severe bicyclist outcomes. Police reports of collisions are the primary source for crash data when used for engineering purposes. While police reported crash data is known to have problems with underreporting, it is often the most complete data source and provides necessary details for informing engineering treatments, such as the location of the collision and dynamics between the parties involved in the crash. The crash data was reviewed and cleaned prior to the analysis. Crashes with missing location information and those that are geocoded as being outside the boundary of states in this study were excluded.

California

California crash data was obtained from Transportation Injury Mapping System (TIMS) for the years 2015-2019. The data included crash level, party level, and victim level datasets containing information on crash severity, geocoded location, vehicle/bicyclist movements, and vehicle/bicycle direction. Only crashes that involved a bicyclist were obtained from TIMS for this analysis. The TIMS dataset does not include property damage only crashes.

Minnesota

Minnesota crash data was obtained from the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) for the years 2015-2019, and filtered to only include crashes that involved a bicyclist. The raw data came in the form of an Excel spreadsheet with each row representing a single crash. Additional party-specific information was in dedicated columns. The data contained information on whether a location was at a signalized intersection as reported by the officer. The data also contained information on severity, motor vehicle movements, and relative direction of travel for bicyclists (riding against, with, or across traffic).

Texas

Texas crash data was downloaded from the Texas Department of Transportation’s (TxDOT) Crash Records Information System (CRIS) for the years 2015-2019 using their Public Query tool. The raw data was provided in a single table including crash, party, and victim information, with victim as unit of analysis. We restructured the data to use the crash as a unit of analysis, with the most severely injured bicyclist and most severely injured motorist details retained for the analysis. If multiple bicyclists and motorists had the same severity level, then the attributes for the first unit involved were retained. Texas data does not have details on bicyclist movement or the relative direction of travel.

Roadway and Contextual Data

Land Use Context

Land use was classified into an approximation of urban, suburban, and rural for each crash based on the Census tract where the crash occurred. Tract level data from the U.S Census formed the basis for this dataset. The U.S. Census classifies tracts into rural and “urban” (which broadly encompasses all urbanized areas). We then subdivided urbanized tracts into higher intensity urban and lower intensity suburban land use based on their average National Walkability Index (NWI) score. The land use context classified at tract level is based on the following criteria:

- Rural – Tracts classified as rural by the U.S. Census

- Suburban – Tracts classified as urban by the U.S. Census and with average NWI score less than or equal to 10.5 (classified as “least walkable” in NWI map)

- Urban – Tracts classified as urban by Census and with average NWI score greater than 10.5

The purpose of this land use classification variable was to understand how crash patterns and relationships between factors included in this analysis vary in urban vs. suburban vs. rural contexts.

Functional Class

Open Street Map (OSM) data were used for streets networks of all three states and functional classification of the street segments was assigned as shown in the Table 1.

Table 1. Functional Class and OSM Functional Classification

| Functional Class | OSM Functional Classes |

|---|---|

| Major Arterials | Trunk, Primary |

| Minor Arterial | Secondary |

| Collector | Tertiary |

| Local | Residential, Living Street, and Unclassified |

We excluded segments that are classified as ‘motorway’ in OSM data, as those do not typically have signalized intersections and are not in the scope of this study. We also excluded segments where motor vehicles are restricted from the analysis (e.g., ‘footway’, ‘cycleway’, ‘path’, ‘pedestrian’), alleys and service roads (‘service’), and all other OSM designations (e.g., ‘track’, ‘bridleway’, ‘steps’).

Traffic Signal Data

Minnesota’s dataset contained officer-reported information on the presence of traffic signals at intersections; California’s and Texas’s crash datasets did not. Because this study focuses on bicyclist safety at signalized intersections, it was important to be able to identify and analyze crashes occurring at signalized intersections separately from all other location types.

Traffic signal location data was obtained from OpenStreetMap (OSM). OSM is a crowd-sourced dataset with information about the transportation network around the world. Coverage varies based on the level of

__________________

0 National Walkability Index (https://www.arcgis.com/apps/mapviewer/index.html?layers=afd7bc8719b84fa897cd6a651c96d37b)

activity among volunteer data collectors in a region, though in general, the data quality tends to be high, especially in urban and developed areas. Where there are inaccuracies, they usually arise from missing or incomplete data; in other words, the data are more likely to have a missing value for intersection control (absence of a signal, implying unsignalized) than have the wrong type of information.

The traffic signal location data in OSM was used to ascertain whether crashes occurred near a signalized intersection. For urban areas, any crash involving a bicyclist that was within 200 feet of a signalized intersection was included the analysis. For suburban and rural areas, which tend to have larger intersections and longer block lengths, any crash that was within 250 feet of a signalized intersection was included.

To validate this decision, we compared signalization status for bicycle intersection crashes within Minnesota, for which we have both OSM signalization status and officer-reported traffic control device information. As shown in Table 2, among the crashes where there is a signal present in OSM, 65% of those in urban areas are consistent with officer-reported traffic control and 35% are inconsistent with the officer report. In suburban areas, 72% are consistent, and in rural areas, 75% are consistent. Among crashes where OSM does not indicate that a signal is present, 90% of those in urban areas concur with officer reports (88% suburban, 92% rural). Only 10% of urban crashes happened at an officer-reported signalized intersection where no signal was indicated in the OSM data. Given that both officer-reported attributes and OSM data may contain errors, it is impossible to say what percent of the inconsistent crash report—OSM signalization statuses may be false positives or false negatives. However, our positive experience using OSM data in the past, as well as the limitations of other statewide data sources (including the lack of statewide signalization layers), encourage us that these data provide the best option for helping to understand bicycle-motor vehicle crashes at signalized intersections a statewide level.

Table 2. Signalization Status in Minnesota

| Signalization Status | Urban | Suburban | Rural |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crashes near signal feature in OSM | 1,121 | 240 | 57 |

| % of OSM signalized that AGREE w/crash report (officer says signalized) | 65% | 72% | 75% |

| % of OSM signalized that DISGREE w/crash report (officer says unsignalized) | 35% | 28% | 25% |

| Crashes NOT near signal feature in OSM | 1,479 | 552 | 373 |

| % of OSM unsignalized that AGREE w/crash report (officer says unsignalized) | 90% | 88% | 92% |

| % of OSM unsignalized that DISAGREE w/crash report (officer says signalized) | 10% | 12% | 8% |

Descriptive Statistics Crash Analysis

The descriptive crash analysis consists of tabulations on key variables of interest to identify attributes that are linked to crashes and crash severity. The descriptive analysis reviewed the following factors: Crash Severity, Lane Use Context, Functional Classification, and Bicycle-Vehicle Interaction.

The analysis summary below is focused on crashes that occur at signalized intersections. A crash was assumed to occur at an intersection if it was within 200 or 250 feet of a signal for urban or suburban/rural areas, respectively.

Crash Severity

A summary of crashes by bicyclist injury severity is given below for each state (see Table 3, Table 4, and Table 5). Note that California data from TIMS does not contain Property Damage Only (PDO, or “O”) crashes, so the total crashes for California given below exclude those crashes. Even in the two states (Minnesota, Texas) that included PDO crashes, the vast majority (more than 85%) of crashes still resulted in at least a possible injury, underscoring that bicyclists are vulnerable road users and highly susceptible to injury in a crash.

Table 3. Bicycle Crashes by Severity, California

| Crash Severity | # Crashes | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Killed (K) | 176 | 1.0% |

| Serious Injury (A) | 1203 | 6.7% |

| Minor Injury (B) | 8409 | 46.8% |

| Possible Injury (C) | 8173 | 45.5% |

| Total* | 17961 | 100% |

*The total for California represents only K, A, B, C crashes

Table 4. Bicycle Crashes by Severity, Minnesota

| Crash Severity | # Crashes | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Killed (K) | 8 | 0.6% |

| Serious Injury (A) | 89 | 6.3% |

| Minor Injury (B) | 568 | 40.0% |

| Possible Injury (C) | 573 | 40.4% |

| Property Damage Only (O) | 180 | 12.7% |

| Total | 1418 | 100% |

Table 5. Bicycle Crashes by Severity, Texas

| Crash Severity | # Crashes | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Killed (K) | 54 | 1.2% |

| Serious Injury (A) | 400 | 9.3% |

| Minor Injury (B) | 1721 | 39.8% |

| Possible Injury (C) | 1445 | 33.4% |

| Property Damage Only (O) | 593 | 13.7% |

| Unknown | 113 | 2.6% |

| Total | 4326 | 100% |

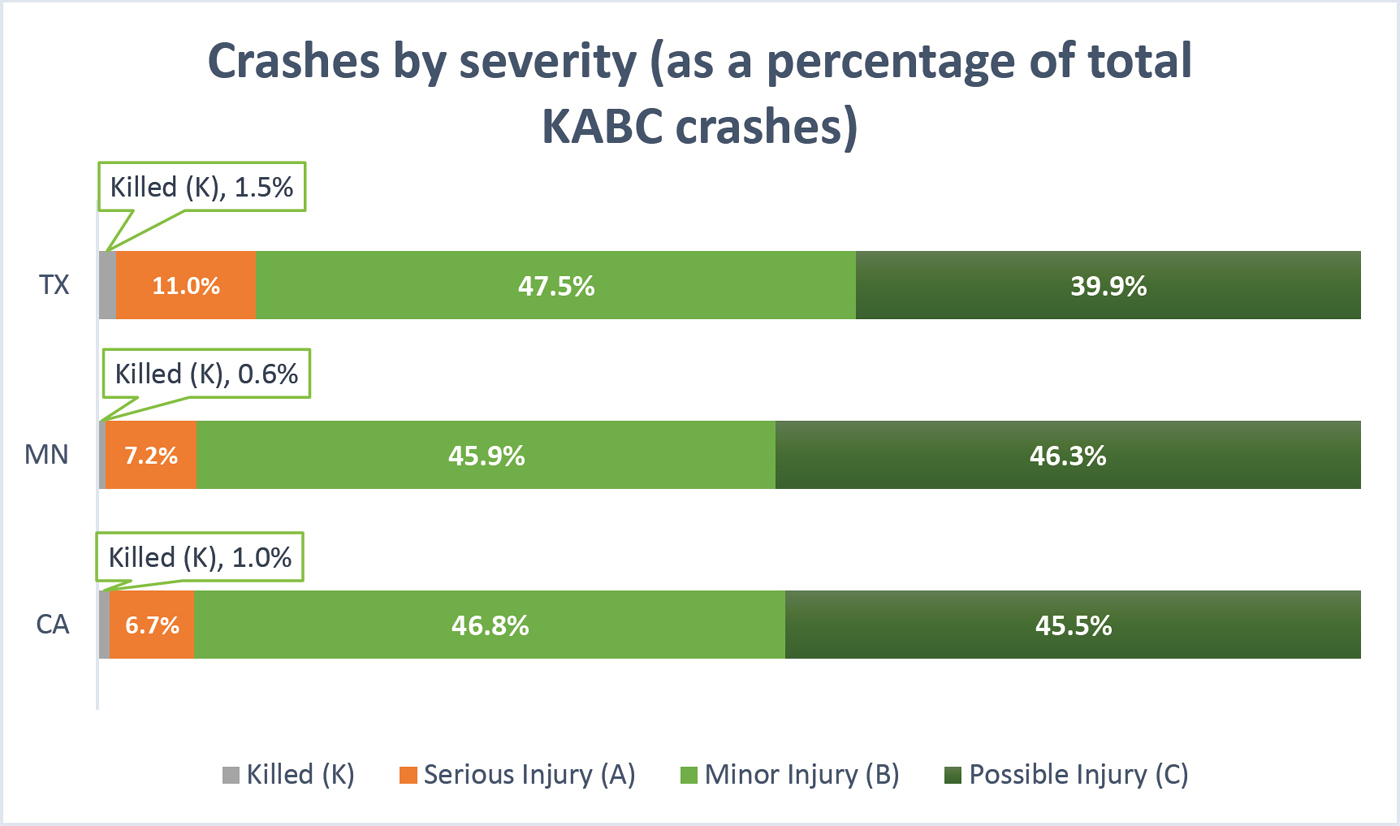

Figure 1 shows a comparison of crash severity between each state. Property Damage Only (O) crashes are excluded in the results presented for all three states. Bicycle-motor vehicle crashes in Texas appear to be more severe on average than California or Minnesota, with nearly 1.5% resulting in death and an additional 11% resulting in serious injury (12.5% Killed or Seriously Injured). By contrast, Minnesota’s and California’s severity distributions are quite similar with about 7.7% of crashes in California and 7.8% of crashes in Minnesota resulting in death or serious injury.

Land Use Context

The tables below show how crash severity varies in each land use context. Specifically, Fatal or Serious Injury (“KA Crashes”) can be compared to “All Crashes.” Each table also provides the percentage of population living within each land use context. For each state, we calculated ratios by population for each land use category to see whether crashes were over- or under-represented by population within that category. This helps us understand the distribution of crashes even while the population distributions by land use category vary state to state. We also calculated the percentage of crashes within each land use category that resulted in death or serious injury.

Across all three states, we observed that both severe bicycle crashes and all bicycle crashes were overrepresented in urban areas, by factors ranging from 1.24 (KA crashes in California) to 2.3 (all crashes in Minnesota). Crashes were correspondingly lower in both suburban and rural areas. The severity of crashes in both California and Texas worsened across the urban—rural gradient, though rural crashes in Minnesota diverged from this trend. This means that, on average, if a bicycle-motor vehicle crash occurs in a suburban or rural area, it has a greater likelihood of resulting in death and serious injury than a crash occurring in an urban area (far right column in the tables below). To be clear, the magnitude of crashes happening in urban areas is much larger than suburban or rural areas, such that both the number and percentage of severe crashes happening in urban areas is greater than suburban and rural combined.

Nonetheless, the higher likelihood of a crash being severe if it does occur in suburban and rural areas is noteworthy and may be driven by larger, faster roads with fewer dedicated facilities for bicyclists. Further, the relative increased severity in suburban and rural areas in California and Texas is in the range of 1.25 to 2 times more likely to be severe. This suggests that suburban and rural signalized intersection dynamics may be somewhat different from urban areas.

Table 6. Crash Severity by Land Use Context, California

| Land Use Context | % of Population | # KA Crashes | % KA Crashes | Ratio, % KA Crashes / % Pop. | # All Crashes | % All Crashes | Ratio, % All Crashes / % Pop. | % KA Crashes / All Crashes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | 70.4 % | 1207 | 87.5% | 1.24 | 16364 | 91.1% | 1.29 | 7.4% |

| Suburban | 19.2 % | 138 | 10.0% | 0.52 | 1348 | 7.5% | 0.39 | 10.2% |

| Rural | 10.4 % | 34 | 2.5% | 0.24 | 249 | 1.4% | 0.13 | 13.7% |

| Total | 100% | 1379 | 100% | 1.00 | 17961 | 100% | 1.00 | 7.7% |

Table 7. Crash Severity by Land Use Context, Minnesota

| Land Use Context | % of Population | # KA Crashes | % KA Crashes | Ratio, % KA Crashes / % Pop. | # All Crashes | % All Crashes | Ratio, % All Crashes / % Pop. | % KA Crashes / All Crashes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | 34.1 % | 74 | 76.3% | 2.24 | 969 | 78.3% | 2.30 | 7.6% |

| Suburban | 26.9 % | 19 | 19.6% | 0.73 | 213 | 17.2% | 0.64 | 8.9% |

| Rural | 39.0 % | 4 | 4.1% | 0.11 | 56 | 4.5% | 0.12 | 7.1% |

| TOTAL | 100% | 97 | 100% | 1.00 | 1238 | 100% | 1.00 | 7.8% |

Table 8. Crash Severity by Land Use Context, Texas

| Land Use Context | % of Population | # KA Crashes | % KA Crashes | Ratio, % KA Crashes / % Pop. | # All Crashes | % All Crashes | Ratio, % All Crashes / % Pop. | % KA Crashes / All Crashes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | 28.7 % | 247 | 54.4% | 1.89 | 2174 | 60.1% | 2.09 | 11.4% |

| Suburban | 46.5 % | 184 | 40.5% | 0.87 | 1310 | 36.2% | 0.78 | 14.0% |

| Rural | 24.8 % | 23 | 5.1% | 0.21 | 136 | 3.8% | 0.15 | 16.9% |

| TOTAL | 100% | 454 | 100% | 1.00 | 3620 | 100% | 1.00 | 12.5% |

Functional Class

Intersection crashes were joined to up to six (6) streets within a search distance of 200 feet (urban areas) or 250 feet (suburban and rural areas). This join accommodates multi-legged intersections while also setting some geographic boundaries to reduce the occurrence of unrelated streets being linked to an intersection crash. The tables below show the maximum functional classification (Table 9) or combination of maximum and minimum functional classification (Table 11, Table 12, and Table 13) for the streets joined to each signalized intersection crash, grouped by state.

Table 9 shows the percentage of mileage of each functional classification to illustrate the relative proportionality of the network in each state. While percentage of mileage is not a perfect comparison because this analysis only looked at crashes near signalized intersections, it is provided to have a reference point. Across all three states, we found that major and minor arterials are the highest functional classification present at the intersection for an overwhelming majority of severe (e.g. approx. 92% in California) and all crashes (e.g. approx. 91% in California). However, major and minor arterials only comprise between 11 and 18% of the street network. In contrast, crashes on collector and local streets comprise less than 10% of all severe crashes, but more than 80% of the roadway network. The small proportion of each state’s total roadway mileage consisting of arterials (and the accompanying intersections) suggests an even greater concentration of crashes on these functional class types than the crash statistics alone communicate.

Table 9. Percentages of Mileage, KA crashes, and All crashes by highest functional class

| Maximum Functional Classification | CA | MN | TX | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Mileage | % KA Crashes | % All Crashes | % Mileage | % KA Crashes | % All Crashes | % Mileage | % KA Crashes | % All Crashes | |

| Major Arterial | 6.8% | 55.3% | 54.8% | 5.0% | 55.7% | 49.1% | 7.2% | 49.4% | 46.6% |

| Minor Arterial | 8.3% | 36.6% | 36.2% | 5.9% | 35.0% | 38.1% | 10.6% | 46.9% | 49.1% |

| Collector | 11.9% | 7.3% | 8.0% | 23.8% | 9.3% | 12.5% | 5.1% | 3.5% | 4.1% |

| Local | 73.0% | 0.4% | 0.8% | 65.3% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 77.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% |

| Missing Data | 0.4% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |||

Delving deeper into the combinations of maximum and minimum functional class, we see that the top two combinations in each state involve an arterial (major or minor) intersecting with a local or collector street (see Table 10). These combinations represent a majority of KA crashes in all three states: 60.8% in California, 69.1% in Minnesota, and 60.4% in Texas. This finding may partly reflect exposure; bicyclists may avoid arterial + arterial intersections, or bicyclists may gravitate towards collector/local streets with signalized crossings at arterials but then not have enough protection at those arterial intersections. The combination with the smallest number of crashes occurs at intersections of collector/local + collector/local, which may be due to a combination of factors – fewer signalized intersections where these street classes intersect, but also the tendency for these intersections to have lower volumes and be designed for lower speeds, both of which result in less opportunity for conflicts and crashes. The following tables (Table 11, Table 12, and Table 13) provide additional details for combinations of functional class for each state.

Table 10. Functional Class Combinations

| Functional Class Combination | CA | MN | TX | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # KA Crashes | % KA Crashes | # KA Crashes | % KA Crashes | # KA Crashes | % KA Crashes | |

| Arterial + Collector/Local | 838 | 60.8% | 67 | 69.1% | 274 | 60.4% |

| Arterial + Arterial | 430 | 31.2% | 21 | 21.6% | 163 | 35.9% |

| Collector/Local + Collector/Local | 106 | 7.7% | 9 | 9.3% | 17 | 3.7% |

Table 11. Maximum/Minimum Functional Classification, California

| Maximum Functional Classification | Minimum Functional Classification | # KA Crashes | % KA Crashes | # All Crashes | % All Crashes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Arterial | Local | 295 | 21.4% | 3701 | 20.6% |

| Major Arterial | Collector | 161 | 11.7% | 2013 | 11.2% |

| Major Arterial | Minor Arterial | 190 | 13.8% | 2510 | 14.0% |

| Major Arterial | Major Arterial | 117 | 8.5% | 1618 | 9.0% |

| Minor Arterial | Local | 225 | 16.3% | 2926 | 16.3% |

| Minor Arterial | Collector | 157 | 11.4% | 2081 | 11.6% |

| Minor Arterial | Minor Arterial | 123 | 8.9% | 1496 | 8.3% |

| Collector | Local | 61 | 4.4% | 927 | 5.2% |

| Collector | Collector | 40 | 2.9% | 517 | 2.9% |

| Local | Local | 5 | 0.4% | 143 | 0.8% |

| Missing Data | Missing Data | 5 | 0.4% | 29 | 0.2% |

| Total | 1379 | 100.0% | 17961 | 100.0% |

Table 12. Maximum/Minimum Functional Classification, Minnesota

| Maximum Functional Classification | Minimum Functional Classification | # KA Crashes | % KA Crashes | # All Crashes | % All Crashes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Arterial | Local | 25 | 24.8% | 233 | 18.8% |

| Major Arterial | Collector | 19 | 19.6% | 193 | 15.6% |

| Major Arterial | Minor Arterial | 6 | 6.2% | 118 | 9.5% |

| Major Arterial | Major Arterial | 4 | 4.1% | 64 | 5.2% |

| Minor Arterial | Local | 9 | 9.3% | 145 | 11.7% |

| Minor Arterial | Collector | 14 | 14.4% | 210 | 17.0% |

| Minor Arterial | Minor Arterial | 11 | 11.3% | 117 | 9.5% |

| Collector | Local | 3 | 3.1% | 66 | 5.3% |

| Collector | Collector | 6 | 6.2% | 89 | 7.2% |

| Local | Local | 0 | 0.0% | 3 | 0.2% |

| Missing Data | Missing Data | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Total | 97 | 100.0% | 1238 | 100.0% |

Table 13. Maximum/Minimum Functional Classification, Texas

| Maximum Functional Classification | Minimum Functional Classification | # KA Crashes | % KA Crashes | # All Crashes | % All Crashes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Arterial | Local | 76 | 16.7% | 519 | 14.3% |

| Major Arterial | Collector | 55 | 12.1% | 416 | 11.5% |

| Major Arterial | Minor Arterial | 70 | 15.4% | 587 | 16.2% |

| Major Arterial | Major Arterial | 23 | 5.1% | 165 | 4.6% |

| Minor Arterial | Local | 67 | 14.8% | 577 | 15.9% |

| Minor Arterial | Collector | 76 | 16.7% | 588 | 16.2% |

| Minor Arterial | Minor Arterial | 70 | 15.4% | 613 | 16.9% |

| Collector | Local | 6 | 1.3% | 70 | 1.9% |

| Collector | Collector | 10 | 2.2% | 78 | 2.2% |

| Local | Local | 1 | 0.2% | 7 | 0.2% |

| Missing Data | Missing Data | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Total | 454 | 100.0% | 3620 | 100.0% |

Bicycle-Vehicle Interaction

In this section, we first summarize the relationships between vehicle movement (left-turn, right-turn, straight, other/unknown) and crash severity in all three states. We then take a deeper dive in all three states to examine how vehicle movement and crash severity vary in different land use contexts and based on functional classification present at an intersection. Finally, we focus on the additional attributes (bicyclist relative direction and bicyclist movement, only available in California) to investigate how these factors may impact crash severity.

Vehicle Movement and Crash Severity

This section summarizes the relationships between vehicle movement (left-turn, right-turn, straight, other/unknown) and crash severity. The following three tables show that, across all three states, crashes with motorists going straight result in the highest number of both overall and severe crashes. Additionally, while crashes involving a right-turning motorist are more common (i.e. higher % of All crashes) than crashes involving a left-turning motorist, crashes with a left-turning motorist are more likely to be severe (i.e. higher % of All crashes that are KA). Because officers occasionally code the motorist movement as “going straight” if they had completed their turn before the crash, turning movement crashes can sometimes be underreported in crash data and our data may overestimate the true prevalence of going straight crashes and underestimate the prevalence of both left-turning and right-turning crashes. However, the findings presented here mirror other research on bicycle crashes and represent our best understanding of driver movements related to crash frequency and severity.

__________________

0 Thomas, L., Nordback, K., and R. Sanders. 2019. “Bicyclist Crash Types on National, State, and Local Levels: A New Look.” Transportation Research Record, 2673(6), 664–676. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361198119849056 and Seattle Department of Transportation. 2020. City of Seattle Bicycle and Pedestrian Safety Analysis: Phase 2. https://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/SDOT/VisionZero/SDOT_Bike%20and%20Ped%20Safety%20Analysis_Ph2_2420(0).pdf

Table 14. Crash Severity by Vehicle Movement, California

| Vehicle Movement | # KA Crashes | % KA Crashes | # All Crashes | % All Crashes | % of all crashes that are KA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left Turn | 186 | 13% | 2706 | 15% | 6.9% |

| Right Turn | 223 | 16% | 5685 | 32% | 3.9% |

| Straight | 832 | 60% | 6670 | 37% | 12.5% |

| Other/Unknown | 138 | 10% | 2900 | 16% | 4.8% |

| Total | 1379 | 100% | 17961 | 100% | 7.7% |

Table 15. Crash Severity by Vehicle Movement, Minnesota

| Vehicle Movement | # KA Crashes | % KA Crashes | # All Crashes | % All Crashes | % of All crashes that are KA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left Turn | 20 | 21% | 252 | 20% | 7.9% |

| Right Turn | 13 | 13% | 335 | 27% | 3.9% |

| Straight | 55 | 57% | 481 | 39% | 11.4% |

| Other/Unknown | 9 | 9% | 170 | 14% | 5.3% |

| Total | 97 | 100% | 1238 | 100% | 7.8% |

Table 16. Crash Severity by Vehicle Movement, Texas

| Vehicle Movement | # KA Crashes | % KA Crashes | # All Crashes | % All Crashes | % of All crashes that are KA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left Turn | 71 | 16% | 638 | 18% | 11.1% |

| Right Turn | 49 | 11% | 803 | 22% | 6.1% |

| Straight | 328 | 72% | 2151 | 59% | 15.2% |

| Other/Unknown | 6 | 1% | 28 | 1% | 21.4% |

| Total | 454 | 100% | 3620 | 100% | 12.5% |

Vehicle Movement and Land Use

The following tables (Table 17, Table 18, and Table 19) show how crash frequency (all crashes) and severity (KA crashes) vary by land use content and vehicle movement, adding nuance to the prior discussion (“Vehicle Movement and Crash Severity”). For example, when looking at all land uses combined, crashes involving a motorist going straight were both the most prevalent and severe in all three states, and crashes involving a right-turning motorist were more prevalent, but less severe. However, there are nuances that emerge for the data when we examine it by land use context by state. For example, the percentage of severe crashes involving turning vehicles (left or right) is higher in suburban and rural areas than in urban areas in California and Texas, but not in Minnesota. Similarly, the ratio of left-turning to –right-turning crashes in terms of the percentage severe varies by land use context and state. For example, Texas has a higher percentage of severe left-turn crashes than other states across the land use contexts – and particularly in rural and suburban areas.

Table 17. Crash Severity by Land Use and Vehicle Movement, California

| Land Use Context | Vehicle Mvmnt | KA Crashes | All Crashes | % Crashes w/in Land Use Context | % Severe Crashes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | KA | All | |||

| — urban | Straight | 743 | 54% | 62% | 6,048 | 34% | 37% | 12% |

| Left Turn | 164 | 12% | 14% | 2,498 | 14% | 15% | 7% | |

| Right Turn | 186 | 13% | % | 5,110 | 28% | 31% | 4% | |

| Other/Unknown | 114 | 8% | 9% | 2,708 | 15% | 17% | 4% | |

| — suburban | Straight | 74 | 5% | 54% | 525 | 3% | 39% | 14% |

| Left Turn | 14 | 1% | 10% | 163 | 1% | 12% | 9% | |

| Right Turn | 31 | 2% | 22% | 494 | 3% | 37% | 6% | |

| Other/Unknown | 19 | 1% | 14% | 166 | 1% | 12% | 11% | |

| — rural | Straight | 15 | 1% | 44% | 97 | 1% | 39% | 15% |

| Left Turn | 8 | 1% | 24% | 45 | 0% | 18% | 18% | |

| Right Turn | 6 | 0% | 18% | 81 | 0% | 33% | 7% | |

| Other/Unknown | 5 | 0% | 15% | 26 | 0% | 10% | 19% | |

Table 18. Crash Severity by Land Use and Vehicle Movement, Minnesota

| Land Use Context | Vehicle Mvmnt | KA Crashes | All Crashes | % Crashes w/in Land Use Context | % Severe Crashes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | KA | All | |||

| — urban | Straight | 41 | 42% | 55% | 371 | 30% | 38% | 11% |

| Left Turn | 17 | 18% | 23% | 204 | 16% | 21% | 8% | |

| Right Turn | 11 | 11% | 15% | 251 | 20% | 26% | 4% | |

| Other/Unknown | 5 | 5% | 7% | 143 | 12% | 15% | 3% | |

| — suburban | Straight | 12 | 12% | 63% | 93 | 8% | 44% | 13% |

| Left Turn | 2 | 2% | 11% | 37 | 3% | 17% | 5% | |

| Right Turn | 2 | 2% | 11% | 63 | 5% | 30% | 3% | |

| Other/Unknown | 3 | 3% | 16% | 20 | 2% | 9% | 15% | |

| — rural | Straight | 2 | 2% | 50% | 17 | 1% | 30% | 12% |

| Left Turn | 1 | 1% | 25% | 11 | 1% | 20% | 9% | |

| Right Turn | - | 0% | 0% | 21 | 2% | 38% | 0% | |

| Other/Unknown | 1 | 1% | 25% | 7 | 1% | 13% | 14% | |

Table 19. Crash Severity by Land Use and Vehicle Movement, Texas

| Land Use Context | Vehicle Mvmnt | KA Crashes | All Crashes | % Crashes w/in Land Use Context | % Severe Crashes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | KA | All | |||

| — urban | Straight | 173 | 38% | 70% | 1,266 | 35% | 58% | 14% |

| Left Turn | 43 | 9% | 17% | 427 | 12% | 20% | 10% | |

| Right Turn | 27 | 6% | 11% | 460 | 13% | 21% | 6% | |

| Other/Unknown | 4 | 1% | 2% | 21 | 1% | 1% | 19% | |

| — suburban | Straight | 140 | 31% | 76% | 818 | 23% | 62% | 17% |

| Left Turn | 24 | 5% | 13% | 185 | 5% | 14% | 13% | |

| Right Turn | 19 | 4% | 10% | 303 | 8% | 23% | 6% | |

| Other/Unknown | 1 | 0% | 1% | 4 | 0% | 0% | 25% | |

| — rural | Straight | 15 | 3% | 65% | 67 | 2% | 49% | 22% |

| Left Turn | 4 | 1% | 17% | 26 | 1% | 19% | 15% | |

| Right Turn | 3 | 1% | 13% | 40 | 1% | 29% | 8% | |

| Other/Unknown | 1 | 0% | 4% | 3 | 0% | 2% | 33% | |

Vehicle Movement and Functional Classification

The following tables (Table 20, Table 21, and Table 22) show how crash frequency (all crashes) and severity (KA crashes) vary by functional classification and vehicle movement. Similar to what we found when reviewing crash frequency and severity by functional classification, the tables below show that while right-turn crashes are more prevalent, they are less severe than left-turn crashes regardless of functional classification – although the difference tends to be larger when a higher classification street is involved. These tables also illustrate that crash types involving a driver going straight are prevalent and disproportionately injurious regardless of the street type, with the exception of arterial/arterial combinations in Minnesota, which have a relatively higher percentage of left-turning severe crashes than both other intersection types in Minnesota and the other states in the analysis.

Table 20. Crash Severity by Functional Classification and Vehicle Movement, California

| Max. Func. Class. | Min. Func. Class. | Vehicle Mvmnt | # Crashes | % Crashes | % Crashes w/in Func. Class. Group | % Severe Crashes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KA | All | KA | All | KA | All | ||||

| — arterial | — arterial | Straight | 261 | 2,075 | 19% | 12% | 61% | 37% | 13% |

| Left Turn | 49 | 684 | 4% | 4% | 11% | 12% | 7% | ||

| Right Turn | 77 | 1,966 | 6% | 11% | 18% | 35% | 4% | ||

| Other/Unknown | 43 | 899 | 3% | 5% | 10% | 16% | 5% | ||

| — collector/local | Straight | 512 | 3,994 | 37% | 22% | 61% | 37% | 13% | |

| Left Turn | 119 | 1,714 | 9% | 10% | 14% | 16% | 7% | ||

| Right Turn | 126 | 3,346 | 9% | 19% | 15% | 31% | 4% | ||

| Other/Unknown | 81 | 1,667 | 6% | 9% | 10% | 16% | 5% | ||

| — collector/local | — collector/local | Straight | 57 | 590 | 4% | 3% | 54% | 37% | 10% |

| Left Turn | 18 | 306 | 1% | 2% | 17% | 19% | 6% | ||

| Right Turn | 17 | 359 | 1% | 2% | 16% | 23% | 5% | ||

| Other/Unknown | 14 | 332 | 1% | 2% | 13% | 21% | 4% | ||

Table 21. Crash Severity by Functional Classification and Vehicle Movement, Minnesota

| Max. Func. Class. | Min. Func. Class. | Vehicle Mvmnt | # Crashes | % Crashes | % Crashes w/in Func. Class. Group | % Severe Crashes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KA | All | KA | All | KA | All | ||||

| — arterial | — arterial | Straight | 9 | 120 | 9% | 10% | 43% | 40% | 8% |

| Left Turn | 7 | 65 | 7% | 5% | 33% | 22% | 11% | ||

| Right Turn | 2 | 77 | 2% | 6% | 10% | 26% | 3% | ||

| Other/Unknown | 3 | 37 | 3% | 3% | 14% | 12% | 8% | ||

| — collector/local | Straight | 40 | 307 | 41% | 25% | 60% | 39% | 13% | |

| Left Turn | 11 | 159 | 11% | 13% | 16% | 20% | 7% | ||

| Right Turn | 10 | 210 | 10% | 17% | 15% | 27% | 5% | ||

| Other/Unknown | 6 | 105 | 6% | 8% | 9% | 13% | 6% | ||

| — collector/local | — collector/local | Straight | 6 | 54 | 6% | 4% | 67% | 34% | 11% |

| Left Turn | 2 | 28 | 2% | 2% | 22% | 18% | 7% | ||

| Right Turn | 1 | 48 | 1% | 4% | 11% | 30% | 2% | ||

| Other/Unknown | - | 28 | 0% | 2% | 0% | 18% | 0% | ||

Table 22. Crash Severity by Functional Classification and Vehicle Movement, Texas

| Max. Func. Class. | Min. Func. Class. | Vehicle Mvmnt | # Crashes | % Crashes | % Crashes w/in Func. Class. Group | % Severe Crashes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KA | All | KA | All | KA | All | ||||

| — arterial | — arterial | Straight | 123 | 844 | 27% | 23% | 75% | 62% | 15% |

| Left Turn | 22 | 199 | 5% | 5% | 13% | 15% | 11% | ||

| Right Turn | 16 | 310 | 4% | 9% | 10% | 23% | 5% | ||

| Other/Unknown | 2 | 12 | 0% | 0% | 1% | 1% | 17% | ||

| — collector/local | Straight | 192 | 1,221 | 42% | 34% | 70% | 58% | 16% | |

| Left Turn | 47 | 398 | 10% | 11% | 17% | 19% | 12% | ||

| Right Turn | 31 | 467 | 7% | 13% | 11% | 22% | 7% | ||

| Other/Unknown | 4 | 14 | 1% | 0% | 1% | 1% | 29% | ||

| — collector/local | — collector/local | Straight | 13 | 86 | 3% | 2% | 76% | 55% | 15% |

| Left Turn | 2 | 41 | 0% | 1% | 12% | 26% | 5% | ||

| Right Turn | 2 | 26 | 0% | 1% | 12% | 17% | 8% | ||

| Other/Unknown | - | 2 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 1% | 0% | ||

Bicycle-vehicle Interaction in California

The data available from California provides additional information regarding the bicycle movement (straight, left-turn, right-turn) and bicycle direction relative to motorist direction (angled, opposite, same direction).

Table 23 below shows that most crashes involve bicyclists going straight (70%) followed by other/unknown (24%), which could indicate that most conflicts arise from when the motor vehicle is turning, rather than the bicyclist, or when a bicyclist is trying to cross an intersection and is hit broadside by a motorist. We also see that crashes involving a bicyclist turning left, regardless of motorist movement, are more likely to be severe than crashes involving a right-turning bicyclist. In tandem with the findings about left-turning motorists discussed above, this finding likely reflects the challenges that accompany a left turn, including needing to find a gap in oncoming traffic that may be high in volume and in speed.

Table 23. Crash Severity by Bike Movement & Vehicle Movement, California

| Bike Movement | Vehicle Movement | KA Crashes | All Crashes | % Severe Crashes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | % w/in Bike Mvmnt | # | % | % w/in Bike Mvmnt | ||||

| — Straight | — Straight | Straight | 550 | 40% | 100% | 4,550 | 25% | 100% | 12% |

| — Turning | Left Turn | 165 | 12% | 50% | 2,319 | 13% | 34% | 7% | |

| Right Turn | 164 | 12% | 50% | 4,440 | 25% | 66% | 4% | ||

| + Other/Unknown | 93 | 7% | 10% | 2,089 | 12% | 16% | 4% | ||

| — Turning | — Straight | Straight | 72 | 5% | 100% | 637 | 4% | 100% | 11% |

| — Turning | Left Turn | 3 | 0% | 60% | 84 | 0% | 41% | 4% | |

| Right Turn | 2 | 0% | 40% | 122 | 1% | 59% | 2% | ||

| + Other/Unknown | 3 | 0% | 4% | 80 | 0% | 9% | 4% | ||

| + Other/Unknown | 327 | 24% | 24% | 3,640 | 20% | 20% | 9% | ||

Table 24 below shows crash severity and total crashes for bicycle direction (relative to motorist direction) and vehicle movement. This table shows two patterns that are common in scenarios where bicyclists are traveling in shared lanes or bikeways parallel to general purpose travel lanes: motor vehicles turning left and bicycle traveling in the opposite direction was more was more prevalent than left-turn motorist and same direction bicyclist; and motor vehicle turning right and bicyclist going same direction was more prevalent than right-turning motorist with opposite direction bicyclist. The findings in the table below also provide nuance for the findings about bicyclist and motorist direction in the table above. For example, while the motorist going straight is the action most likely to result in a severe bicyclist injury regardless of bicyclist movement, the data show that straight motorist movements in “opposite direction” (head-on) crashes are more likely to be severe than “angled” (broadside) crashes, while “same direction” crashes (e.g., sideswipes) are the least likely to be severe. Crashes involving a right-turning vehicle have a similar likelihood of being severe (4-5%) regardless of the direction of the bicycle. Finally, crashes involving a left-turning motorist appear to be more severe when the bicyclist is traveling in an angled or opposite direction (7-8%) compared to the same direction (4%).

Table 24. Crash Severity by Bike Direction and Vehicle Movement, California

| Bike Direction | Vehicle Mvmnt | KA Crashes | All Crashes | % Severe | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | % w/in Bike Direction | # | % | % w/in Bike Mvmnt | |||

| — Angled Direction | Straight | 563 | 41% | 71% | 4,293 | 24% | 43% | 13% |

| Left Turn | 88 | 6% | 11% | 1,256 | 7% | 13% | 7% | |

| Right Turn | 111 | 8% | 14% | 3,114 | 17% | 31% | 4% | |

| Other/Unknown | 35 | 3% | 4% | 1,224 | 7% | 12% | 3% | |

| — Opposite Direction | Straight | 62 | 4% | 32% | 418 | 2% | 17% | 15% |

| Left Turn | 81 | 6% | 41% | 1,040 | 6% | 43% | 8% | |

| Right Turn | 35 | 3% | 18% | 736 | 4% | 30% | 5% | |

| Other/Unknown | 18 | 1% | 9% | 239 | 1% | 10% | 8% | |

| — Same Direction | Straight | 175 | 13% | 54% | 1,673 | 9% | 35% | 10% |

| Left Turn | 13 | 1% | 4% | 298 | 2% | 6% | 4% | |

| Right Turn | 68 | 5% | 21% | 1,604 | 9% | 33% | 4% | |

| Other/Unknown | 66 | 5% | 20% | 1,250 | 7% | 26% | 5% | |

| + Unknown Direction | 64 | 5% | 5% | 816 | 5% | 5% | 8% | |

Summary of Key Findings

Below is a summary of key findings from this state-level crash analysis, focused on crashes occurring at signalized intersections.

- In states that reported property damage only (PDO) crashes (Minnesota and Texas), PDO crashes accounted for less than 15% of crashes, indicating that the vast majority of crashes involving a bicyclist result in at least a possible injury, and too often a severe injury or fatality. This result is unfortunately expected when bicyclists, who are vulnerable road users, are struck by vehicles with larger mass and often velocity, resulting in a high transfer of kinetic energy. Texas had higher rates of serious injury and fatality (approx. 12%) compared to other two states (approx. 8%). This may be because Texas crashes are actually more severe due to wider/faster roads, larger vehicles, age/illness-related factors, or some other characteristic; however, it could also be because Texas police departments may be less likely to report lower severity crashes, or because Texas residents may be less likely to call the police to report lower severity crashes.

- Most crashes (approx. 80-90% in CA and MN and 60% in TX) occur in urban areas, and on a per-population basis, crashes are over-represented in urban areas. For example, approximately 34% of the population lives in urban areas in Minnesota, but 78% of crashes occur there. This is likely due to more people biking in these areas. While there are many fewer crashes (both overall and when corrected for population) occurring in suburban and rural locations, crashes are more likely to be fatal or severe in rural and suburban areas compared to urban areas in both CA and TX. For example, in California 7% of crashes are severe in urban areas, while 10% and 14% are severe in suburban and rural locations, respectively.

- Major and minor arterials were present at the intersection for the overwhelming majority of crashes (between 87 and 96%); however, roadway miles of streets of this classification account or only 11-18% of street network in the three states, indicating that a disproportionate number of crashes occur at intersections that have a major or minor arterial. The small proportion of each state’s total roadway mileage consisting of arterials (and the accompanying intersections) suggests an even greater concentration of crashes on these functional class types than the crash statistics alone communicate.

- When examining combinations of functional classifications at intersections, we found that locations where arterial streets intersect with either collector or local streets resulted in the highest number of serious injury and fatal crashes (60.8% in California, 69.1% in Minnesota, and 60.4% in Texas of KA crashes).This finding may either be because of exposure (i.e. more people biking on these streets) or because these intersections provide less protection to bicyclists.

- In all states, the most common vehicle movement in crashes between a bicyclist and a motorist involved a motorist going straight (between 37% and 59%). These crashes also tended to have the highest relative severity, with 11.4%-15.2% resulting in death or serious injury. While the focus of this research is on conflicts/crashes between turning motorists and bicyclists, these findings suggest that there is a need for additional research on safety for conflicts between motorists going straight and bicyclists.

- In all states, the second most common motorist movement was a right turn, at between 22% and 32% of movements, followed by a left-turn, which represented 15% to 20% of all crashes. While left-turn crashes are less prevalent, they are twice as likely to result in a serious injury or fatality compared to right-turn crashes. However, even non-severe crashes erode bicyclist safety on the roadway and can discourage ridership, so our research will continue to examine both left- and right-turning crashes.

- We will use the findings herein to help hone the next phase of analysis.

Study Limitations and Next Steps

This analysis looked at crash totals only, not accounting for exposure or bicycle facility type. Where possible, we added information to provide additional context (e.g., population distribution, percentage of mileage for each functional classification). While these variables help contextualize the findings, they are not a replacement for measuring exposure. The micro crash analysis that is underway and will be completed this year will include bicycle exposure to help answer additional questions about how risk factors relate to exposure. As is common with all crash analysis, officer reported information is sometimes incomplete or incorrect.

We found that bicyclist crashes are overwhelmingly occurring in urban areas, and while suburban and rural bicycle crashes tend to be more severe (between one and a half to two times more). Knowing these patterns across land use intensities and understanding motorist movements preceding a crash will inform how we extrapolate design guidance for signalized intersections from urban areas to suburban and rural areas using results from the micro crash analysis and conflict analysis.