Economic and Social Mobility: New Directions for Data, Research, and Policy (2025)

Chapter: 2 Early Life and Family

2

Early Life and Family

The family is the first institution in which investments in children occur; it is the earliest “incubator” of human capital. As such, children’s experiences in their family environments are central to their developmental trajectories and to their prospects for economic and social mobility.

Contemporary American families are characterized by a diversity of living arrangements, household structures and compositions, and kin and nonkin relationships, both within and between households, and these arrangements have become increasingly fluid over time (Berger & Carlson, 2020; Seltzer, 2019). Childhood environments also vary substantially by socioeconomic status, which both reflects and determines differential access to resources (Lareau, 2002, 2011; Roksa & Potter, 2011). This variation often stems from social, economic, and psychosocial factors that determine parental opportunities and constraints, thereby affecting parental behaviors and investments (Kalil & Ryan, 2020).

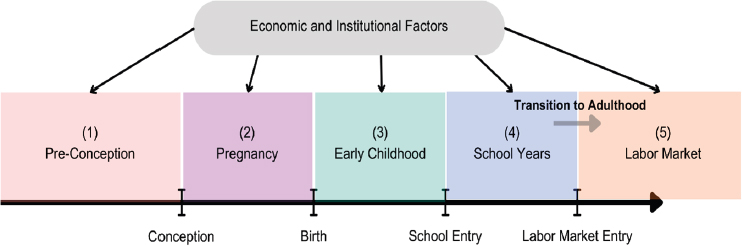

This chapter summarizes the evidence about the potential early life and family determinants of intergenerational economic and social mobility. Intergenerational mobility focuses on human capital or labor market outcomes (i.e., occupation or earnings) in adulthood. These outcomes are the result of the cumulation of life experience leading up to that point. As shown in Figure 2-1, the early life determinants of economic and social mobility begin even before conception (phase 1), include factors shaping pregnancy (phase 2), and span the more commonly studied early childhood period (phase 3). Moreover, strong theoretical reasons suggest that factors occurring earlier in the life course may causally shape mobility. For example, the circumstances shaping the period before conception—including

access to contraception and abortion—affect when a pregnancy occurs and with whom it occurs, and the economic and social circumstances into which a child is born and raised. Those circumstances interact with other social, economic, and institutional factors to shape early childhood, the school years (Figure 2-1, phase 4), and, eventually, transition to adulthood, including the child’s own fertility and family formation patterns, with labor market outcomes (phase 5). In addition, each of these periods is itself influenced by laws and policies, institutions, social norms, and social and economic conditions, which shape intergenerational mobility differently by race and ethnicity, immigration status, socioeconomic status, geography or state of residence, and other characteristics.

The committee’s review focuses primarily on absolute mobility—in particular, upward mobility from socioeconomic disadvantage (see Chapter 1 for detailed definitions). The reason is twofold: first, the persistence of disadvantage across generations is a relevant social problem in the United States; second, much research to date focuses on low-income and minority families. The committee expands this focus to also consider persistence of advantage (i.e., the mechanisms that high-income families use to provide advantages to their children, which support the persistence of privileged status). We also consider relative mobility, i.e., the association between parents’ and adult children’s economic circumstances at the societal level, when appropriate.

As explained in Chapter 1, relative mobility characterizes groups rather than specific individuals (much like inequality). Much of the evidence about relative mobility is indirect and focuses on known mediators of mobility rather than mobility itself. For example, if an economic support intervention targeted at families with children increases high school graduation among disadvantaged children, it is inferred that the intervention has the potential to increase occupational status or labor market earnings among these children (upward mobility), and, ultimately, decrease the persistence of disadvantage at the societal level (relative mobility). This is considered

indirect evidence because the underlying research does not directly measure absolute mobility but a correlated pathway.

This chapter ends with a review of policy-relevant research for addressing these important issues. Early childhood education programs and reproductive health policies show promise for increasing upward intergenerational mobility, while pregnancy risk reduction programs and abstinence education programs are less promising. Economic support policies and programs show promise for increasing upward mobility across generations, while the evidence on parenting interventions shows limited impact. Understanding both the landscape of how early life and family circumstances shape children’s life trajectories and the policies that may show impact in improving outcomes over the life course is essential for a policy-relevant research agenda on economic and social mobility.

Although there are strong theoretical reasons to believe that associations of early life and family contexts with intergenerational mobility reflect causal effects, it is difficult to randomize (or find quasi-experimental variation in) many factors that could play an important causal role in these relations (e.g., “parenting”). Additionally, examining mobility requires data following individuals over extended periods of time in order to include at least two generations. When available, this chapter notes evidence based on experimental and quasi-experimental approaches that support the assessment of causal relationships on early life outcomes that mediate the mobility process, such as school attendance, educational achievement, educational attachment, disciplinary issues, and others. We also present correlational evidence when evidence supporting causal interpretation is not available. Most of the empirical evidence focuses on relations of early life and family with key aspects of human capital, health, and well-being that are critical mediators in the intergenerational mobility process. The chapter also considers the largely quasi-experimental evidence regarding policies that promote healthy development in early life and family wellbeing and, by extension, suggest plausible pathways for mobility. On the whole, the available evidence suggests that policies that increase access to contraception and family planning, high-quality early education and care programs, and economic support are particularly promising for enhancing intergenerational mobility among those who grow up at the bottom of the economic ladder.

THE CIRCUMSTANCES OF PREGNANCY

Although largely absent from scholarly discussions about social and economic mobility, the circumstances of conception and childbirth—including social, economic, and institutional factors—are highly likely to influence parents’ partnership decisions, mental health, schooling and career

trajectories, economic status, and financial security. These circumstances in turn affect the intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic status and children’s chances for upward or downward mobility. The committee believes that this report makes a unique contribution by examining the connections between the circumstances of childbirth and economic and social mobility.

One common characterization of the circumstances of conception relates to a definition adopted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Unintended pregnancies are defined as those that occur sooner than desired or when no child was planned at that time or at any point in the future. In recent years, however, research has moved away from using the term intention and has shifted toward language that more closely aligns with how this information is gathered on surveys or research instruments (Kost & Zolna, 2019; Maddow-Zimet & Kost, 2020; Potter et al., 2019). To represent the literature as precisely as possible, this chapter uses the terms unintended, mistimed, unwanted, and desired or undesired to reflect the terminology used in the specific research articles being summarized.

As recently as 2015, about 40 percent of all pregnancies in the United States occurred either sooner than desired or when no pregnancy was desired at any point in the future (Kost et al., 2023). Prior to the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization in July 2022—which has allowed 20 states to restrict or eliminate abortion access (McCann et al., 2024)—about 40 percent of unintended pregnancies ended in abortion (Finer & Zolna, 2016; Kost & Lindberg, 2015).

Unintended pregnancies are strongly associated with mediators of intergenerational mobility, including adverse health, environmental, and economic circumstances in childhood. Children born from unintended pregnancies are disproportionately likely to have low birth weight and other birth complications (Kost & Lindberg, 2015; Mohllajee et al., 2007). Older children experience poorer-quality home environments after the unplanned birth of a younger sibling (Barber & East, 2009, 2011).

Unintended pregnancy and childbirth are also disproportionately followed by parental union dissolution, family complexity, instability in parents’ romantic partnerships, and multiple-partner fertility (Guzzo & Hayford, 2020). Having an “unwanted” (as defined in the referenced article) child is correlated with higher levels of maternal depression and lower levels of happiness (Barber et al., 1999), as well as with a higher likelihood of harsh parenting styles (Gipson et al., 2008). Children whose births were unintended tend to have lower self-esteem and more frequent depression than their planned-birth peers (Axinn et al., 1998; David, 2006). Although the bulk of this literature is descriptive, theory suggests that at least some

of the adverse relations between pregnancy intentions and outcomes are potentially causal.

FAMILY CIRCUMSTANCES AT BIRTH AND SUBSEQUENT FAMILY EXPERIENCES

The circumstances in which children are conceived, born, and raised vary considerably in the U.S. population. For example, more than two-thirds of births to married women result from intended pregnancies, compared with less than a quarter of births to cohabiting couples and less than a tenth of those to “single women,” who are neither married to nor living with the child’s father (Guzzo, 2021). These stark differences are shaped by social, economic, and institutional factors, including access to and knowledge of contraception. While roughly half of nonmarital births in the United States occur to cohabiting couples, the majority of such unions dissolve relatively early in children’s lives (Sassler & Lichter, 2020).1 Moreover, unintended pregnancies that result in childbirth are more likely to occur among women who are economically disadvantaged (Mosher et al., 2012), including younger and less educated women, and racial/ethnic minorities. Today, approximately 87 percent of first births to women over 30 occur within marriage, but the same is true for only 27 percent of first births to women younger than 24 (Brown, 2022).

There are also stark differences by maternal education and race and ethnicity in the circumstances in which births occur. Women with a high school degree or less education are half as likely as women with a college degree or more education to have their first birth within marriage, about three times more likely to have their first birth in the context of cohabitation, and nearly five times more likely to have their first birth while neither living with nor married to the child’s father. White women are nearly three times more likely than Black women and about 30 percent more likely than Hispanic women to have their first birth while married. Black and Hispanic women are, respectively, 75 and 15 percent more likely than White women to have their first birth while cohabiting and 4.5 and 2.5 times more likely to have their first birth while neither married nor cohabiting (Brown, 2022).

___________________

1 Demographic trends in the United States (and other wealthy countries) show a sharp rise in age at first marriage and age at first birth, as well as an increase in cohabitation prior to and in lieu of marriage (Bailey et al., 2014; Guzzo & Hayford, 2020). Yet, the delay in marriage has been greater than that in first births, such that a large proportion of births, particularly those to younger women (under age 30), occur outside of marriage, with roughly half to unmarried women and half to cohabiting couples.

Immigrants display higher fertility rates than U.S.-born women2 and tend to give birth and raise children in very different family circumstances. Although immigrant families have disproportionately low socioeconomic status in terms of income, education, and employment, immigrant women tend to be older, on average, than U.S.-born women at the time of their first births and are much more likely to have marital than nonmarital births (Livingston, 2016). Yet, over time, immigrants, particularly second- and third-generation immigrants, become increasingly likely to marry and form families with native-born Americans (rather than other immigrants) and to see their divorce rates rise (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [National Academies], 2015).

Differences in the circumstances in which pregnancies and births occur are associated with differences in the circumstances in which children are raised. Less socially and economically advantaged groups are not only disproportionately likely to have nonmarital births and births at younger ages, but they also exhibit lower rates of marriage and long-term parental partnerships; higher rates of parental union dissolution and divorce; and greater family complexity, instability, and multiple-partner fertility (Smock & Schwartz, 2020). Family instability (changes in household composition and parents’ romantic partners and spouses), in turn, is thought to be a key mechanism linking nonmarital births to subsequent family dynamics and child development (Cherlin & Seltzer, 2014; McLanahan & Sawhill, 2015; Mitchell et al., 2015; Osborne & McLanahan, 2007; Seltzer, 2019). Notably, however, some evidence suggests that family instability plays a larger role in development for White children than for Black children (Fomby & Cherlin, 2007), and that the social and economic gains associated with marriage are larger for White than Black children and families (Fomby, 2024). Nonetheless, unintended pregnancy and nonmarital childbirth are, on average, associated with a host of factors that are thought to influence inter- and intragenerational economic and social mobility (Cooper & Pugh, 2020). As such, Fomby (2024) characterizes marriage as “both a product and a driver of social inequality” (p. 1285).

An extensive body of research documents that children who are raised in two–biological parent, married families exhibit advantages in numerous domains of development and success throughout the life course—potentially because such families are able to invest greater financial resources and time in children and to provide more consistent child-rearing environments

___________________

2 The total (lifetime) fertility rate in 2019 for immigrants was 2.02 children, compared with 1.69 children for native-born individuals. Moreover, the 2019 birth rate (percent of women who gave birth) for immigrant women aged 15–44 was 5.7 percent, whereas it was 4.8 percent for native-born women (Camarota & Zeigler, 2021). On the whole, immigrants account for nearly a quarter of annual births, while representing less than 15 percent of the U.S. population.

throughout childhood (e.g., see Kearney, 2023, for a recent review). Despite an ongoing debate over whether relations of family structure with children’s outcomes are causal in nature, it is well established that less-advantaged adults find themselves in fertility and family formation contexts that are associated with high levels of family instability (parental breakup and repartnering, multiple-partner fertility). In turn, children born to unmarried parents, on average, are at risk of poorer health, development, and wellbeing throughout the life course.

Research shows that the primary dividing factor in the family formation context is educational attainment; in particular, those with at least a college degree exhibit markedly different fertility and family formation patterns and, in turn, family contexts and child-rearing environments, from those of individuals with less educational attainment (Kearney, 2023; McLanahan, 2004; McLanahan & Jacobsen, 2014). McLanahan and Jacobsen (2014) argue that this divergence has been driven by changes over time in (a) ideational orientations toward gender roles, sexual behavior, and marriage; (b) diminished labor market prospects for low-skilled men relative to those for low-skilled women, which has implications for marriage markets; and (c) social welfare policies. Empirically, Edin and Kefalas (2005) draw on semistructured interviews and participant observation with 162 single mothers to shed light on the decline in marriage and rise of single parenthood in the past few decades. They find that, while mothers tend to think of marriage as a capstone institution that they aspire to—but only after they are financially secure—they tend to be less willing to wait for parenthood, which they view as central to a fulfilling life.

Notably, while the general pattern that children raised in two–biological parent, married families exhibit advantages and experience better outcomes relative to peers raised in other family circumstances holds across racial/ethnic groups, research suggests that the relationship may not be similarly causal across groups. Cross et al. (2022), for example, highlight that factors such as racism and male-centric social structures jointly influence family formation patterns, access to resources, family stress, parenting behaviors, and child development in ways that make identification of the “effects” of family structure on child development for racial minorities (in particular, Black families) problematic. Relatedly, Torche and Abufhele (2021) find that the negative effect of nonmarital fertility on infant health declines as marital fertility becomes less prevalent, suggesting that part of the marriage premium for children might be contextual, depending on how normative marriage is in a given society.

Cross (2020) shows that socioeconomic characteristics meaningfully explain (in an accounting sense) the differential relationship between family structure and on-time high school completion for Black children, implying that father absence may be less independently salient for Black families. In

addition, Cross (2023) found a relatively small overall association between family structure and educational achievement among Black adolescents, albeit with some variation by family economic resources, suggesting that any impact of family structure might be relatively muted for Black Americans. Other studies suggest that Black families experience smaller disadvantages associated with single motherhood than White families, whereas Hispanic families experience larger disadvantages. In addition, some evidence suggests that other social and economic risk factors are more strongly associated with economic disadvantage for Black and Hispanic families than for White families, regardless of family structure (Baker, 2022; Williams & Baker, 2021).

In sum, an extremely large body of research, albeit predominantly correlational in nature, demonstrates associations of nonmarital births and family instability with poorer outcomes in childhood and early adulthood, which vary in size from modest to large, suggesting that nonmarital fertility and family stability are associated with opportunities for upward mobility (or lack thereof) for low-income children. Similarly, greater family stability may provide an avenue for high-income families to pass their advantages to their children. Family context might also influence the level of relative mobility. In aggregate-level analyses, Chetty et al. (2014a) found that the factor most strongly correlated with upward economic mobility across U.S. communities was growing up in a neighborhood characterized by a lower fraction of single-parent families. Interestingly, this association was observed for children growing up in single-parent and two-parent households, suggesting pathways beyond the nuclear family, plausibly related to families as role models and sources of social capital at the community level, as anticipated by Wilson (1996) and Coleman (1988), among others. While this correlational evidence does not support the claim that family structure drives upward mobility, it suggests that family environments and their potential implications for mobility may be important at both the individual and community levels.

Some studies—for example, those employing fixed effects and leveraging natural experiments as identification strategies—point to potential causal links between family structure during childhood and adult outcomes (McLanahan et al., 2013). At the same time, it is important to recognize that there is considerable variation in outcomes for children born outside of marriage by subsequent family experiences, including transitions in family composition and involvement by nonresident fathers, coresident step/social fathers, and other kin (grandparents) and nonkin caregivers (Adamsons & Johnson, 2013; Berger & McLanahan, 2015; Dunifon, 2013; Gold & Edin, 2021; Mollborn et al., 2011). Intergenerational linkages in socioeconomic status are weaker in families with stepkin, as households with stepkin engage in lesser intergenerational transfers than those without stepkin

(Schoeni et al., 2022). It is also important to recognize that the majority of studies have focused on children’s outcomes during childhood and, to a lesser extent, young adulthood, with few studies focusing on outcomes well into adulthood (McLanahan & Jacobsen, 2014). Moreover, the committee is not aware of studies to directly identify causal links between family structure and intergenerational mobility at the individual level, although Bloome (2017) shows, descriptively, that adults who did not grow up in a stable two-parent home are disproportionately likely to experience downward mobility and low incomes.

PARENTING, THE CAREGIVING ENVIRONMENT, AND CHILD DEVELOPMENT

Parents influence children’s development and well-being through the child-rearing environment and parenting behaviors they provide. Genetic attributes and predispositions, in isolation, appear to explain only a minority of the variation in individual differences in human development (Duncan et al., 2023), whereas environments and life experiences of parents and children are thought to be considerably more important. These include the preconception and pregnancy periods, as well as contextual social and economic factors (see Figure 2-1). Such environments and life experiences shape how genes are expressed in the context of individuals’ opportunities and challenges, with potential implications for economic and social mobility. That is, intergenerational correlations in well-being are highly influenced by shared environmental exposures and experiences for parents and children, including access to material resources, stress, exposure to toxins, family stability and functioning, health behaviors, and parenting behaviors (Almond & Currie, 2011; Ellis & Boyce, 2008; Reichman & Teitler, 2013; Torche & Nobles, 2024). In particular, high-quality parenting behaviors may buffer against (and low-quality parenting behaviors may exacerbate) unfavorable epigenetic effects of exposure to adversity on children’s development (Provenzi et al., 2020). Yet, because providing high-quality care is both time and emotionally intensive, in addition to being expensive, more-advantaged parents are, on average, able to make greater investments in their children and offer them higher-quality caregiving environments than their less-advantaged counterparts. As such, Wadsworth and Ahlkvist (2015) argue that economic inequality may be a primary cause of disparities in parental behaviors and investments in children and, thereby, in children’s development and human capital formation.

A growing body of evidence suggests that even mild shocks during the prenatal and early childhood periods—which are disproportionately experienced by families of lower socioeconomic status—can have lifelong, potentially causal consequences, although these consequences may vary by

genetic and (subsequent) environmental factors, including family resources and associated exposures that further influence social and biophysiological development (Aizer & Currie, 2014; Almond & Currie, 2011; Almond et al., 2012, 2018; Torche & Nobles, 2024). Early life is a critical period for brain development and the formation of structures and mechanisms that shape cognitive, physical, social, and emotional well-being throughout the life course (National Academies, 2000). Indeed, early childhood experiences are crucial for the development of socioemotional skills and executive function that set the stage for future development (Duncan et al., 2023). Moreover, child development occurs in cascading fashion, such that early investments provide the scaffolding and skills to support and respond to later investments (and challenges), and development of skills in one domain facilitates development of skills in other domains (Cunha et al., 2006; Heckman, 2006, 2008). As such, socioeconomic gaps in development in early childhood typically do not narrow, and may even compound, over time (Bradbury et al., 2015).

The relationship between parent (or primary caregiver) and child is, generally, the most important factor for early childhood development. High-quality parenting is characterized by three key dimensions: warmth and responsiveness, support for child autonomy, and well-defined behavioral expectations coupled with consistent age-appropriate feedback (Kiernan & Mensah, 2011; Moullin et al., 2018). It is composed of high levels of affection, patience, and nurturing; support for child exploration and interests; provision of enriching activities, materials, and educational support; promotion of skill development through positive reinforcement; and setting of clear and consistent rules that reflect children’s abilities and are explained and (re)enforced through reasoning, persuasion, and nonphysical discipline (Baumrind, 1971; Bornstein, 2019; Kalil & Ryan, 2020; Ulferts, 2020). Children experiencing such parenting exhibit better cognitive, educational, and socioemotional outcomes, including greater self-esteem and less anxiety, depression, and engagement in antisocial behaviors; they are also more successful as adults (Bornstein, 2019; Clayborne et al., 2021; Madigan et al., 2019; Masud et al., 2019; Spera, 2005).

Parental warmth and responsiveness, particularly in the early years of life, help children attain a sense of security, regulate their emotions, and develop frameworks for exploring their environments (Morris et al., 2017; Moullin et al., 2018; Sroufe et al., 2010). As such, parental emotional support has been linked to greater educational achievement and attainment (Drake et al., 2014; Ogg & Anthony, 2020). Parental emotional support is also associated with children’s development of self-confidence and self-esteem (Zakeri & Karimpour, 2011) and, thereby, their ability to cope with adversity (Moran et al., 2018). Parenting behaviors that include language-rich communications, use of decontextualized language, turn-taking,

age-appropriate help with emotion regulation, and opportunities for child autonomy have also been strongly linked to positive developmental outcomes (see, e.g., Bornstein, 2019).

In short, extant research indicates that, across childhood, parental warmth, responsiveness, supportiveness, appropriate monitoring and supervision, flexibility, and autonomy-granting are associated with better socioemotional health, cognitive skills and academic achievement, and educational attainment. In contrast, harsh parenting and behavioral control are associated with poorer outcomes in these domains (Gorostiaga et al., 2019; Majumder, 2016; Masud et al., 2015). Yet, as will be discussed further because high-quality parenting behaviors are time and labor intensive, wealthier and more highly educated parents are considerably more likely to engage in such behaviors than their less-advantaged counterparts. Wealthy parents are also more likely to engage in a range of activities to secure advantages for their children. As shown by qualitative research based on interviews and participant observations, advantaged parents enroll children in enrichment activities, coach them, and negotiate with educational and other institutions to secure benefits for their children (Calarco, 2018; Lareau, 2011). Moreover, their children tend to imitate these behaviors, beginning as early as the preschool years (Calarco, 2018; Streib, 2011).

Racial/ethnic differences in maternal parenting behaviors have also been well documented, with the most pronounced differences reflecting cognitive support and stimulation (language use, conversation, reading; Brooks-Gunn & Markman, 2005). Notably, however, observed differences in parenting behaviors by race and ethnicity and immigrant status are likely confounded by differences in parental socioeconomic status and associated differential selection into fertility, family formation, and subsequent childrearing contexts, as well as by experiences with racism and discrimination (which are typically unobserved in existing quantitative studies). Moreover, there is considerable variation in parenting behaviors by socioeconomic status within racial/ethnic groups, and research on between-group differences in parenting behaviors for parents of similar socioeconomic status has produced inconsistent results (Brooks-Gunn & Markman, 2005; Gibbs & Downey, 2020; Lareau, 2011). Nonetheless, racial/ethnic differences in parenting behaviors appear to explain a nontrivial portion—half to two-thirds—of racial/ethnic differences in school readiness, which have lifelong implications for success. For the most part, associations between parenting behaviors and school readiness are relatively similar across racial/ethnic groups, albeit with some exceptions (Brooks-Gunn & Markman, 2005; Gibbs & Downey, 2020). Moreover, differences in parenting behaviors by both socioeconomic status and race and ethnicity are thought to reflect substantial differences in parental opportunities (the extent to which parents’ choice sets are constrained) and stress, each of which influences parenting

behaviors. That is, parenting behaviors reflect the contexts in which families live, such that lower-income and non-White families disproportionately experience lower-quality and more stressful environments (housing, neighborhoods) and institutional supports (childcare, schools), which affect parental well-being (stress, mental health, cognitive load) and behaviors, as well as the home environment. Such differences in family context, in concert with historical and contemporary public policies, enable more advantaged parents to access, acquire, and leverage goods and services, social networks, and economic and social opportunities to promote their children’s upward mobility that are unavailable to less-advantaged parents (Reeves, 2018). In turn, socioeconomic status and parenting behaviors function both independently and interactively to shape child development and life chances (Brooks-Gunn & Markman, 2005; Gibbs & Downey, 2020).

When considering the evidence linking parenting behaviors with children’s subsequent development, and its potential implications for economic and social mobility, it is crucial to recognize that the vast majority of research on parenting behaviors has focused on mothers; considerably less attention had been paid to the behaviors of resident and nonresident fathers (Cabrera et al., 2018), or to other resident or nonresident kin (grandmothers) or nonkin caregivers (Dunifon, 2013; Mollborn et al., 2011; Tach et al., 2014). Given the high levels of family diversity, complexity, and fluidity that characterize contemporary American families (Berger & Carlson, 2020), including considerable growth in the proportion of children who spend time in a household that includes one or more grandparents (Harvey et al., 2021; Pilkauskas, 2012, 2014; Pilkauskas & Cross, 2018), future research would be well served by examining the caregiving behaviors of a wider range of individuals, with a focus on their potential contributions to child development and, in turn, mobility. Considering the role of extended family may be especially salient with respect to non-White populations (Cross, 2018; Cross et al., 2018).

IMPLICATIONS OF SOCIOECONOMIC DIFFERENCES IN PARENTING

Parental investments of financial resources and time matter for children’s development and life chances. Parental financial resources shape the goods and services parents purchase to promote their children’s development. Yet, disparities by socioeconomic status in parental expenditures in the United States are substantial and have widened significantly over time. The average difference in expenditures on enrichment activities for children between families in the highest and lowest income quintiles more than tripled between the early 1970s and mid-2000s, from an annual gap of approximately $2,700 per child to an annual gap of roughly $7,500 per child (Duncan & Murnane, 2011).

Differences in expenditures reflect the fact that parents of higher socioeconomic status have greater resources with which to acquire more and better goods and services, including neighborhoods, housing, food, medical care, childcare, and schooling, among others. However, differences in choices made by parents of higher and lower socioeconomic status may also reflect differences in knowledge of age-specific developmental needs, as well as in parental health, mental health, and stress, and family functioning and stability (Berger & Font, 2015), and access to social networks and related opportunities (Reeves, 2018). That is, in addition to facing more stringent budget constraints, parents of lower socioeconomic status may have less information, knowledge, skills, social connections, and opportunities for selecting high-quality options to promote child development than those of higher socioeconomic status (Case & Paxson, 2002; Kalil & Ryan, 2020; Reeves, 2018). This may be particularly salient for immigrant families (Cabrera et al., 2021).

Parents also provide physical care and cognitive and emotional stimulation, play with children, and arrange and accompany children in activities. On average, parents of higher socioeconomic status devote substantially more time to these activities than their counterparts of lower socioeconomic status (Dotti Sani & Treas, 2016; Guryan et al., 2008). Through the course of these activities, higher socioeconomic status parents provide greater cognitive and emotional stimulation, warmth, responsiveness, and consistency, and engage in less harsh parenting and physical discipline (Kalil & Ryan, 2020; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2021; Reeves & Howard, 2013; Yoshikawa et al., 2012). Differences in these behaviors are thought to predominantly reflect differences in economic context. Economic scarcity is associated with psychological distress that undermines the quality of parental support and parent–child interactions, including by inducing cognitive biases such that, in the context of economic scarcity, parents are more likely to make decisions based on short- rather than long-term objectives and less likely to engage in purposeful, goal-directed parenting (Crnic & Coburn, 2019; Kalil & Ryan, 2020). Also, in the context of low-quality or unsafe neighborhoods, parents are more likely to exhibit what is conventionally considered poorer-quality (Furstenberg et al., 1999; Ludwig et al., 2012) and authoritarian parenting behaviors, perhaps in part to protect their children (Doepke & Zilibotti, 2019). Parenting behaviors can also change in response to living in safer neighborhoods (Darrah & DeLuca, 2014; DeLuca et al., 2016).

Exposure to economic precarity and low-quality environments and institutions, in turn, is thought to both directly and indirectly (via stress experienced by both parents and children) adversely influence children’s neurological and biological development, with long-term implications for cognitive and socioemotional development (Atkinson et al., 2015; Duran et

al., 2020; Thompson, 2014). Notably, whereas causal evidence of the effects of income on parenting behaviors, on average, is lacking, a growing body of research indicates that income is causally linked to both child maltreatment–related behaviors and to child protective services involvement (Berger et al., 2017; Bullinger et al., 2023; Cancian et al., 2013; Rittenhouse, 2023; Wildeman & Fallesen, 2017).

In short, parents of higher socioeconomic status spend more time engaged in child-focused activities, provide more cognitive simulation and emotional support to children, and use less harsh discipline than their counterparts of lower socioeconomic status. They are also able to access greater social and educational opportunities for their children. These differences reflect greater financial constraints and higher levels of stress, which are associated with poorer functioning (greater cognitive load, impaired executive function), and may result in greater parental anxiety and depression, as well as cognitive biases and impulsive decision making (Kalil & Ryan, 2020), which are thought to be core mechanisms linking family resources with child development (Kiernan & Mensah, 2011). Specifically, evidence suggests that parenting practices (cognitive stimulation, control, harsh discipline) mediate associations of socioeconomic status with socioemotional and cognitive development, including executive function (Baker & Brooks-Gunn, 2020), and that parental emotion dysregulation is associated with lower-quality parenting and, in turn, with emotion dysregulation among children (Shaw & Starr, 2019).

Given substantial differences in the contexts to which families of higher and lower socioeconomic status are exposed, socioeconomic status–related disparities in development and well-being emerge in the prenatal period and persist throughout life, spanning physical and mental health, cognitive and socioemotional functioning, educational achievement and attainment, employment and earnings, and a host of other domains (Berger et al., 2009; Bradbury et al., 2019; Case et al., 2002; Fletcher & Wolfe, 2016; Washbrook et al., 2014). Notably, whereas most research on associations between parenting behaviors and child development has been correlational in nature, strong theoretical underpinnings and some, albeit limited, evidence (e.g., Björklund et al., 2010; Fiorini & Keane, 2014) suggest plausible causal effects. The large literature linking exposure to adverse social and economic environments (and shocks therein), from the prenatal period onward, to poor outcomes throughout the life course is also suggestive of causal relations (Aizer & Currie, 2014).

In sum, diverse factors connect socioeconomic disadvantage to less than optimal parenting practices, which, in turn, predict children’s socioemotional and cognitive development. These intermediate outcomes then predict long-term educational and economic outcomes in adulthood, including high school graduation and labor market earnings. While no studies to

date examine all of these pathways jointly, the literature reviewed on each specific pathway strongly suggests that parenting practices are implicated in the persistence of both advantage and disadvantage across generations.

EFFICACY OF EARLY LIFE AND FAMILY POLICIES AND PROGRAMS IN SHAPING THE DETERMINANTS OF ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL MOBILITY

A range of policies and programs has the potential to influence the circumstances in which pregnancy occurs and children are born, as well as children’s subsequent family and early life experiences, with potential implications for their health, development, and well-being and, thereby, life chances. The two major approaches to reducing unplanned (and, in particular, teen) pregnancy are (a) promoting sexual abstinence or pregnancy risk reduction through education and (b) increasing access to effective contraception and abortion.

A pressing policy question relates to how Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022) will affect the multitude of factors in the first three life phases depicted in Figure 2-1. There has been little evidence on this question given the short amount of time between the Dobbs decision in 2022 and the publication of this report in 2025. Although the historical record may not apply directly to the post-Dobbs era, evaluations of previous policy changes restricting or increasing access to abortion or contraception provide the best available evidence and guidance on this question. We provide a high-level summary of this evidence here.

Despite a substantial decline in teen births in the United States in recent decades (Hamilton et al., 2023), the evidence on (teen) pregnancy prevention education programs on the whole indicates that they have largely been ineffective at reducing pregnancy, particularly programs that promote abstinence only (Chin et al., 2012; Juras et al., 2019; Marseille et al., 2018).

In contrast, the evidence on policies and programs to increase access to effective contraception has been quite promising (Bailey, 2013; Flynn, 2023; Kelly et al., 2020; Lindo & Packham, 2017; Sawhill, 2014), suggesting that granting greater legal and financial access to contraception and legal access to abortion has direct causal effects on unintended pregnancy and childbirth (Ananat & Hungerman, 2012; Bailey, 2013; Guldi, 2008). Moreover, programs and policies that increase access to contraception and abortion directly raise parents’ education, employment, and economic and financial security, and reduce dependence on public assistance (Ananat & Hungerman, 2012; Bailey, 2006, 2013; Bailey et al., 2012, 2018; Miller et al., 2020). They also appear to causally affect partnership and marriage decisions by altering the timing of marriage, choice of parenting partner, and marital stress, thereby influencing the stability of those partnerships,

including their likelihood of union dissolution and divorce (Bailey et al., 2018; Christensen, 2011; Goldin & Katz, 2002; Rotz, 2016).

Increased access to family planning programs in the 1970s appears to have causally raised the economic resources available to children and reduced child poverty (Bailey et al., 2018). Because parents’ individual education and employment decisions, as well as their partnership decisions, affect the resources and environments available to children across the life course (Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997; Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997; Duncan et al., 2011), there are strong theoretical reasons to suggest that access to contraception and abortion have implications for upward mobility of disadvantaged children. While this body of research has not directly examined intergenerational mobility as an outcome, it has found that greater access to contraception affected determinants of intergenerational mobility. That is, the culmination of the effects of mothers’ greater contraceptive access resulted in their children going on to attain higher rates of college completion, labor-force participation, wages, and family incomes as adults (Bailey, 2013).

Even today, differential fertility patterns across groups are thought to, at least in part, reflect differential access to the full range of existing contraceptive options. A recent randomized controlled trial found that eliminating out-of-pocket costs for contraception for uninsured women—making all contraceptive options free—raised the use of any birth control by 40 percent, doubled the value of the birth control purchased, increased days covered by purchased birth control, and had a significant effect on the efficacy of the contraceptive methods used (Bailey et al., 2023). The study also found that making contraceptives free had large and similar effects on contraceptive efficacy across a broad set of subgroups, including stratifications by Hispanic ethnicity, education, relationship/marital status, motherhood, and religiosity. In short, causal evidence suggests that changes in access to contraception in today’s policy context may have important effects on a number of mediators of intergenerational mobility, especially upward mobility from disadvantaged backgrounds (see Figure 2-1).

Of course, not all unplanned pregnancies result in a birth. Prior to the Dobbs decision, about 40 percent of unintended pregnancies ended in abortion (Finer & Zolna, 2016; Kost & Lindberg, 2015). It will be important for future research to examine whether changes to state-level abortion policies in the aftermath of the 2022 Dobbs decision affect fertility and family formation patterns, particularly for teens and disadvantaged populations.

Evidence on the causal effects of abortion policy stems from legalization of abortion in the 1960s and early 1970s. Abortion was first legalized in a subset of states and then in the remaining states in January 1973 with Roe v. Wade. According to the Guttmacher Institute, nearly 20 percent of pregnancies ended in abortion during the first year following Roe v. Wade,

and this share rose to 30 percent over the next decade, before decreasing through today (Henshaw & Kost, 2008). Research finds that abortion legalization led to a 5–8 percent reduction in the birth rate of women of childbearing age (Angrist & Evans, 1996; Levine et al., 1999). Some evidence also suggests that increased abortion access translated into changes in women’s socioeconomic outcomes, with potential implications for economic and social mobility. Angrist and Evans (1996), for example, show that abortion reform appears to have improved schooling and labor market outcomes among Black women, although the statistical strength of these results tempers their conclusions.

Beyond access to contraception and abortion, policies and programs that promote marriage and healthy relationships have sought to increase the proportion of children born within marriage, to encourage marriage once pregnancy or childbirth has occurred, and to assist couples in engaging in high-quality relationships and maintaining their marriages. These programs have largely been targeted to populations of lower socioeconomic status, which are disproportionately at risk of nonmarital birth, parental union dissolution, and family complexity, including multiple-partner fertility. A substantial body of research over the past two or more decades has documented that these initiatives have not, in general, produced promising results with respect to increasing marriage, family stability, parenting quality, or parental relationship quality. This likely reflects, at least in part, low take-up rates in most programs, although results across programs and program sites have been heterogeneous (Avellar et al., 2018; Halpern-Meekin, 2019; Lundquist et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2018; Randles, 2016; Wood et al., 2012, 2014). Evaluations of recent federal and state initiatives in this arena are ongoing, and additional evidence of their impacts, when available, will further inform the efficacy of such programs.

Once children are born, policies and programs addressing parenting, economic support, and early childhood education and care have the potential to promote high-quality parenting and early life experiences, both by increasing family economic resources and by providing direct services to parents and children (see Figure 2-1, phase 3). Such interventions aim to improve parental education; employment; earnings; time and financial investments in children; and other aspects of parenting quality such as cognitive support, warmth, and responsiveness, as well as child cognitive and socioemotional skills. Parenting interventions take a wide range of forms and vary considerably in terms of intended target populations (defined by child age, parent and child characteristics, “risk” factors, etc.); intended duration and intensity of delivery; mode of delivery (in-home, classroom based, virtual; whether they are provided independently or in concert with another early education and care or school-based program); program quality; curricula, behaviors, skills, and outcomes targeted (parent–child

relationships and interactions; child cognitive skills, socioemotional development, health); staff qualifications; cost; and scalability. This heterogeneity makes it difficult to evaluate the efficacy of parenting programs writ large.

With these caveats in mind, evidence suggests that, on the whole, parenting interventions, including most home visiting programs, have shown inconsistent and limited impacts on child development and well-being, likely at least in part due to low take-up and engagement rates, although direct effects on parents have been somewhat more promising (Berger & Font, 2015; Duncan et al., 2023; Kalil & Ryan, 2024; Ryan & Padilla, 2019). As such, there is little reason to suspect such programs, in their current forms, have substantial impacts on economic and social mobility, although the committee is aware of no studies to assess such effects directly. Future research in this area is warranted given the importance of parental stress and mental health for understanding parental investments and parenting quality (Kalil, 2014a,b; Kalil & Ryan, 2024).

Research on the role of economic support programs has produced much more promising findings. Such programs transfer income or in-kind resources that may either assist parents in purchasing goods and services that promote child health and development or provide such goods and services directly. Core economic support programs in the United States include the Child Tax Credit (CTC); Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC); Unemployment Insurance; Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly the Food Stamp Program [FSP]); Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF); Child Support Services; Supplemental Security Income; and health care programs, such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. In addition to (or as a result of) increasing recipient families’ resources, some such programs (including CTC, EITC, SNAP, WIC, and Medicaid) have been shown to reduce stress and improve emotional well-being, parental investments of time and money in children, parenting quality (including reducing child maltreatment), and child health and development (see summaries in Duncan et al., 2023; National Academies, 2023a,b), all of which are plausible mechanisms for supporting upward mobility. Evidence that such programs appear to affect these core mechanisms (family resources, stress, parenting quality, early childhood health and development) suggests that they may have positive impacts on intra- and intergenerational mobility. Although child support is a leading antipoverty program, evidence regarding its impact on mobility is currently limited (see Box 2-1).

A growing body of recent research leveraging exogenous variation in program rollout, expansion, and eligibility and access provides direct evidence that economic support programs—most notably tax transfers (CTC, EITC), SNAP/FSP, and Medicaid—have plausibly causal effects on

BOX 2-1

Child Support and Mobility

The Title IV-D child support program, which facilitates child support transfers, serves nearly 13 million children annually, making it the “third-largest human services program affecting children” in the United States (McDonald et al., 2024, p. 2). Moreover, although more than half of families with child support orders do not receive the full amount they are due, and that about a third receive none of the support they are due (Grall, 2020), child support receipt and, by extension, the child support program, has been shown to substantially reduce poverty among recipient families (Cancian & Meyer, 2018; McDonald et al., 2024). Child support receipt has also been found to be positively and reciprocally (bidirectionally) correlated with nonresident parent (typically father) involvement with children (Nepomnyaschy, 2007), as well as to be positively associated with recipient children’s well-being (Nepomnyaschy et al., 2022). However, data limitations and barriers to identifying suitable counterfactual conditions against which to isolate causal effects of child support receipt on children’s developmental and, in particular, on their adult outcomes have precluded causal estimates of the long-term effects of child support receipt. The committee is aware of only one study to examine such effects. Kong et al. (2024) found child support receipt among welfare-participating families to be associated with greater adult earnings for recipient children. Given the scarcity of compelling evidence regarding both causal and long-term effects of child support receipt on adult outcomes, the committee finds that the existing evidence base is inadequate to support conclusions regarding whether child support may impact economic and social mobility or the core mechanisms to which it is related.

mechanisms related to upward mobility. Research indicates that increased parental income from child-related tax benefits during a child’s first year of life results in increased achievement test scores, fewer school suspensions, a higher probability of high school graduation, and greater earnings in adulthood (Barr et al., 2022). Research also shows that EITC receipt during childhood leads to greater educational attainment, employment, earnings, and income, and lower rates of poverty and social welfare program participation in adulthood (Bastian & Michelmore, 2018; Guerrero, 2023; McInnis et al., 2023). Additionally, focusing on the precursor to the Aid to Families with Dependent Children and subsequent TANF programs, Aizer et al. (2016) leverage exogenous variation in access to cash benefits via the Mothers’ Pension program, finding that benefit receipt during childhood resulted in greater education and adult income.

Expanded in utero and early childhood access to and participation in SNAP/FSP has been shown to result in better adult health and greater human capital (educational attainment and occupational status), earnings

and income, economic self-sufficiency (greater employment and less social welfare program participation), and better neighborhood quality, as well as less criminal conviction and incarceration, social welfare program participation, and mortality (Bailey et al., 2020; Barr & Smith, 2023; Hoynes et al., 2016). Access to Medicaid in utero and during childhood has been shown to improve children’s adult health and increase educational attainment, employment, and earnings, as well as to decrease teen births, disability, mortality, and social welfare program participation (Brown et al., 2020; Cohodes et al., 2016; Goodman-Bacon, 2021; Miller & Wherry, 2019). Moreover, recent research has identified intergenerational effects of health care access: a mother’s access to Medicaid while she was in utero or during her childhood improves the birth and infant health of her daughters’ children (East et al., 2023; Noghanibehambari, 2022). Research also shows that access to Medicaid in utero increases second-generation income mobility relative to one’s parents’ position in the income distribution (O’Brien & Robertson, 2018).

Beyond family economic resources and the home environment, high-quality early childhood education and care programs may benefit child development and thereby have implications for subsequent economic and social mobility. Access to childcare has also been shown to increase maternal labor supply (Berlinski et al., 2024; Wikle & Wilson, 2023); to the extent that it increases family income, increased maternal labor supply provides more opportunities to children and thus may also promote mobility. Such programs include center-based childcare for children from birth to age 3 and early education (preschool/prekindergarten) for children aged 3–5 years. Programs may be universal or targeted (means tested), public or private (though potentially publicly subsidized), full or part time, and may vary considerably in terms of teacher qualifications, curriculum, and support for cognitive and socioemotional development.

There is strong evidence from early experimental studies of small-scale, high-quality, and high-intensity programs targeting low-income families that were implemented between the 1960s and 1980s (Abecedarian, High Scope/Perry Preschool, Infant Health and Development Program). These studies show substantial positive effects spanning childhood through adulthood in a wide range of domains, including cognitive and socioemotional skills, educational achievement and attainment, family formation and stability, health, employment and earnings, criminal justice involvement, and participation in social welfare programs (Elango et al., 2015). These studies indicate that children who participated in high-quality early childhood education and care programs had better outcomes in these domains throughout the life course relative to otherwise similar children who did not participate in such programs; however, the studies did not directly assess whether participating children had better outcomes (e.g., education, earnings, income)

than their parents and, thus, whether the programs resulted in upward intergenerational mobility.

Quasi-experimental evidence leveraging county variation in rollout of the Head Start program, which began in the 1960s and targeted children from low-income backgrounds, also suggests substantial long-term effects on human capital development, educational attainment, and economic self-sufficiency, including greater employment and reduced poverty and participation in social welfare programs (Bailey et al., 2021). Moreover, Barr and Gibbs (2022) show that Head Start in the 1960s and 1970s had effects on intergenerational mobility, in that the children of original program participants saw increased educational attainment, lower rates of teen pregnancy, and reduced criminal engagement; the authors estimated that these factors increased these children’s wages in adulthood by 6–11 percent.

Evidence suggests that contemporary early childhood education and care programs, on the whole, help prepare children for entry into kindergarten and primary school, but that program quality and associated effect sizes vary considerably. Moreover, short- and long-term effects, when found, tend to be largest for the least advantaged children, children of immigrants, and dual-language/English-learning children, as well as for programs using domain-specific rather than generalist (“whole child”) curricula. Large-scale randomized evaluations of the Head Start (for 3- to 5-year-olds from low-income backgrounds) and Early Head Start (for children under age 3 years from low-income backgrounds) programs—the largest public early childhood education and care programs in the United States—have demonstrated short-term benefits in cognitive skills, socioemotional skills, and health that are largest (and most likely to persist) for the least advantaged children (Love et al., 2013; Puma et al., 2010).

While some studies report that these effects tend to fade during the school age years, this simplistic interpretation belies the methodological challenges associated with the fact that children in the comparison group went on to attend alternative preschools/high-quality care at very high rates (Bitler et al., 2014; Feller et al., 2016; Kline & Walters, 2016; Zhai et al., 2014). That is, a large portion of comparison group children received a fairly comparable (although slightly later) treatment, leading them to catch up to the Head Start group. This has different implications than the conclusion that the benefits for the Head Start group fade over time. Although evidence from these evaluations does not yet extend past primary school, the strongest evidence from quasi-experimental studies suggests that there may be long-term positive effects of Head Start (Bailey et al., 2021; Barr & Gibbs, 2022). In short, while research on the effects of contemporary early childhood education and care programs has shown mixed results, it suggests that high-quality, intensive programs can have positive developmental impacts for disadvantaged children, children of immigrants, and dual-language learners (Duncan et al., 2023).

DATA LIMITATIONS AND OPPORTUNITIES

Recent advances in linking longitudinal administrative data systems have greatly expanded the ability to assess economic and social mobility patterns across generations and to consider the multigenerational roles of factors such as education, income, employment, neighborhood conditions, and access to and participation in social welfare programs (see, e.g., National Academies, 2023b).

While these efforts have facilitated—and will continue to facilitate—innovative research on economic and social mobility, they are limited with respect to assessing the roles of pregnancy and childbearing circumstances, as well as family context, parenting, and early life experiences. As this chapter highlights, whether pregnancies and childbearing are intended, parental resources, such as time and money, and parenting behaviors are likely important determinants of child development and well-being; adult health; social and economic well-being; and intergenerational mobility, especially upward mobility for children from disadvantaged households. Yet, examining how policies and programs affect (potentially causal) relations between parental well-being and intergenerational mobility has been stymied by a paucity of longitudinal survey data supporting the study of intergenerational relationships from the prenatal period onward, across multiple generations. These data limitations constrain researchers’ abilities to identify policies and programs that reduce the intergenerational transmission of inequality. In addition, despite calls for more than a decade for multigenerational research that includes three or more generations (Mare, 2011, 2014; Pfeffer, 2014), the vast majority of evidence continues to be grounded in two-generation models. Further, existing population-based studies of three or more generations typically leverage either administrative data or survey data (most commonly from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics [PSID]), which vary in the extent to which they include high-quality measures of pregnancy or birth intentions or desires, family functioning, parenting behaviors, and child development spanning generations.

Two ongoing longitudinal panel studies in the United States currently follow multiple generations from birth onward: the PSID and the Future of Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFCWS).3 Both the PSID and the FFCWS include economic, demographic, social (including information on pregnancy intendedness), contextual, and biological data on at least two generations; however, to date, comprehensive parenting and child development data are available for only one generation. The PSID has followed a nationally representative sample of individuals and their household members and offspring since 1968 and collected survey data on parenting and

___________________

3 The FFCWS was originally called the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study.

child development for a subsample of children from 1997 to 2008.4 Since 2014, the study has been periodically collecting such data on all children born in sample households in 1997 or later, including those born to children (now adults) comprising the initial (1997–2008) cohort. The FFCWS is a birth cohort study of children born in 20 large U.S. cities between 1998 and 2000.5 These children and their parents have been followed since their births, and survey and biological data are currently being collected on the third generation (children of the initial birth cohort) as soon as possible after their births. Because the FFCWS oversampled nonmarital births (although, when weighted, the data are representative of all births in large cities during the sampling period), the sample is extremely diverse (48% Black, 27% Hispanic, 25% White or other race or ethnicity; 17% non-U.S. born). Both the PSID and the FFCWS are being expanded to include detailed parenting and child development data on children now being born to female sample members. Ongoing data collection on all children born to cohort members—who could be followed from the in utero period onward and assessed at relatively frequent intervals representing key developmental stages of childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood—would greatly enhance research on intergenerational economic and social mobility.

SUMMARY, KEY CONCLUSIONS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The family plays a critical role in the mobility process, serving as the primary institution through which investments are made in children, thus shaping human capital development from the prenatal period onward. Parents are central to this process, investing resources in their children’s upbringing to directly affect their future economic and social prospects. Family environments are highly variable in the United States, largely based on social and institutional factors, family socioeconomic status, and the resources and opportunities they afford.

The circumstances of pregnancy and childbirth are closely linked to the prenatal and childhood environment and parental investments in children. Populations of lower socioeconomic status are disproportionately likely to have unintended and nonmarital births. Unintended pregnancy and childbirth are adversely associated with infant and maternal health, cognitive and human capital development, and social and economic well-being for parents and children. Children resulting from unintended pregnancy and those experiencing single-parent households are disproportionately likely to experience a variety of worse health, family, and economic circumstances.

___________________

Conclusion 2-1: Unintended pregnancies and childbirth are adversely associated with multiple determinants of upward mobility from poverty and persistence of advantage, in domains such as infant and maternal health, cognitive and socioemotional development, human capital formation, and economic well-being.

Parents play a crucial role in shaping children’s development and wellbeing in early life. Parental behaviors—including physical care, cognitive and emotional stimulation, opportunities for child autonomy and age-appropriate play, and activity engagement and arrangement—can require substantial investments of time and resources. Associations of family context and parental investments with child development are well documented, as are associations of child development with social and economic wellbeing throughout the life course, yet most of this research is correlational rather than causal. Socially and economically disadvantaged parents make fewer investments in their children than their more advantaged counterparts, reflecting differential access to resources and differences in their life experiences, as well as contextual social and economic factors. Inequalities emerge before children are born, as disparities in socioeconomic status affect children’s prenatal environments and have lifelong consequences for social and biophysiological development. Although racial/ethnic differences in parenting behaviors have been well documented, these differences may be confounded by disparities in parental socioeconomic status and associated differential selection into parenthood, family formation, and subsequent child-rearing contexts, as well as by experiences with racism and discrimination (which are typically unobserved in existing quantitative studies).

Conclusion 2-2: Socioeconomic disparities in parenting behaviors and resources are associated with disparities in the social and economic well-being of children throughout the life course, thus providing a mechanism for the persistence of advantage and disadvantage across generations.

Reproductive health policies and programs that increase access to contraception and abortion are the most promising means of reducing undesired pregnancy and childbirth. Indeed, rigorous evidence suggests that such programs and policies have a variety of causal effects on promoting parents’ and children’s health and social and economic well-being, suggesting their potential to increase upward intergenerational mobility of both parents and their children. In contrast, the evidence on the effectiveness of pregnancy risk reduction programs—and abstinence education programs in particular—has not been encouraging.

Economic support programs—particularly the EITC, SNAP, and Medicaid—are particularly promising for promoting upward mobility for disadvantaged children. Rigorous evidence indicates that such programs have positive effects on the key determinants—including family resources, stress, parenting quality, and early childhood health and development—that link childhood experiences with adult health and social and economic wellbeing; these programs also have direct positive impacts on adult health and social and economic well-being. In contrast, parenting interventions have shown inconsistent and limited impacts on child development and wellbeing, suggesting that such programs, even if scaled, are unlikely to have large population-level effects.

Historical evidence on the benefits of early childhood education, such as Head Start, for upward social mobility is promising, showing positive effects from childhood through adulthood across a wide range of developmental, educational, social, and economic domains. However, evidence on the long-run effects of more recent programs has generally been mixed, in part because of limitations in research designs and the short time horizon during which participating children can be followed.

Conclusion 2-3: Early childhood education programs and reproductive health policies and programs that increase access to contraception and abortion show promise for increasing upward intergenerational mobility. Economic support policies and programs that increase access to financial resources, food, and health care also show promise for increasing upward mobility. In contrast, the evidence on other pregnancy risk reduction, abstinence education, and parenting intervention programs is less encouraging.

Research to date offers limited evidence on whether associations among family context (pregnancy intendedness, family formation, family structure and stability), parenting behaviors and the caregiving environment, child development, and economic and social mobility are causal. Research on the mechanisms through which these factors may operate, such as children’s cognitive and socioemotional development and educational attainment, is also limited, although a growing body of work suggests causal effects on these intermediate factors. Future research needs to expand the use of longitudinal administrative and survey data, and to further employ quasi-experimental approaches and (when possible) randomized controlled trials, with the following goals:

- Further examine the effects of access to contraception and abortion, particularly in the wake of the Dobbs decision and subsequent

- state policies, on the circumstances of pregnancy and childbirth, family dynamics, and parent and child outcomes.

- Leverage exogenous factors that may influence family context and specific parenting behaviors and investments (e.g., by evaluating innovative programs) to identify causal effects of family context and parenting behaviors on child development and economic and social mobility.

- More fully investigate the family context, parenting behavior, and child development mechanisms through which economic support policies may influence economic and social mobility.

- Develop and test the causal assumptions implied by comprehensive models of economic and social mobility that incorporate biological, social, economic, and contextual factors related to early life and family.

Recommendation 2-1: The vast majority of research linking early life and family experiences to intergenerational mobility is descriptive in nature. Researchers should expand the use of existing longitudinal, administrative, and survey data and, when possible, further employ quasi-experimental and experimental approaches to obtain a better understanding of the causal mechanisms through which family context (pregnancy intendedness, family formation, family structure and stability), parenting behaviors and the caregiving environment, and child development affect economic and social mobility, as well as potential heterogeneity in such relationships for demographic subpopulations.

Existing survey and administrative data are not fully adequate for facilitating comprehensive research on malleable pathways through which social and economic (dis)advantages are transmitted within and across generations. The PSID and the FFCWS, which are currently the only ongoing long-term U.S. panel studies to follow multiple generations of family members, are the two primary longitudinal studies currently used to study early life and family. Both studies include economic, demographic, social (including information on pregnancy intendedness), contextual, and biological data on at least two generations; to date, however, comprehensive parenting and child development data are available for only one generation. Both the PSID and the FFCWS need to be maintained and further expanded to include detailed parenting and child development data on subsequent generations of all children born to respondents. Children of respondents need to be followed from the in utero period onward and assessed regularly at intervals representing key developmental stages of childhood, adolescence, and

young adulthood. Such data would provide an efficient means of facilitating studies of multigenerational patterns of economic and social mobility and the range of mechanisms through which they may occur.

Recommendation 2-2: Existing survey and administrative data are not fully adequate to support comprehensive research on intergenerational economic and social mobility and the range of mechanisms through which mobility may occur. Existing longitudinal surveys, such as the Panel Study of Income Dynamics and the Future of Families and Child Wellbeing Study—currently the only long-term ongoing U.S. panel studies to follow multiple generations of family members—should be maintained and expanded to include detailed information on pregnancy intention and the circumstances of pregnancies, parenting, and child development for all children born to current sample members. In addition, the samples that support these surveys should be refreshed with respondents that represent the contemporary population, especially Latino/Hispanic and immigrant subgroups. The children should be followed in utero and onward and assessed regularly at intervals representing key developmental stages of childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. In addition, these surveys should be linked to administrative data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the Internal Revenue Service, and state and federal agencies that administer core social welfare programs.

This page intentionally left blank.