Addressing Workforce Challenges Across the Behavioral Health Continuum of Care: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: Session 2: Health Care Professionals

Session 2

Health Care Professionals

Session 2 focused on the role of health care providers in addressing the challenges within the behavioral health workforce. Several speakers explored various models and strategies aimed at improving care delivery, including the integration of behavioral health into primary care settings, the expansion of roles for different types of health care providers, and the importance of training and supporting these professionals. The session also discussed opportunities for interprofessional teams to address workforce shortages and deliver comprehensive care. See Box 2 for additional highlights.

Anna Ratzliff, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, University of Washington, focused on the critical issues surrounding the behavioral health workforce, particularly at the level of the care provider. She began by framing the discussion around the continuum of behavioral health care settings, emphasizing the importance of understanding where needs are most urgent, from community-based care to specialized services. Ratzliff highlighted the significant unmet needs, especially for those presenting in crisis, and underscored the importance of innovative approaches to identify and bridge these individuals to appropriate services.

She elaborated on the two major approaches to addressing the workforce gap: increasing the available workforce and retaining the current workforce. Ratzliff discussed the need for creative solutions to address workforce shortages, such as training existing professionals with new skills and expanding the roles of nontraditional types of care providers. Additionally, she stressed the importance of continuing to produce new behavioral health care providers who are equipped with the skills necessary for a rapidly evolving landscape.

Box 3

Highlights from Individual Workshop Participants in Session 2

- Addressing behavioral health workforce shortages requires both expanding the workforce and retaining health care providers, emphasizing the need for creative solutions, such as training nontraditional workers. (Ratzliff)

- Integrating primary care and behavioral health care using a biopsychosocial approach can effectively address complex health needs by involving both physical and mental health care in closely coordinated collaborative care. (McDaniel)

- Moral injury, stemming from systemic barriers that prevent health care providers from delivering ethical patient care, is a major issue affecting the well-being of care providers and quality of care delivered. (Dean)

- Behavioral health equity is hampered by a lack of racial diversity among licensed providers, insufficient cultural competence, and a shortage of clinicians who speak languages other than English. (Huang)

- Peer support specialists with lived experience offer valuable insights and improve patient outcomes, but challenges, such as low wages and certification requirements, hinder their full integration into the workforce. (Chapman)

- Clinical pharmacists can play a significant role in managing chronic health conditions and psychiatric medications in Federally Qualified Health Centers, improving patient outcomes through integrated care. (Bateman)

- Workforce attrition in behavioral health is driven by low pay, workplace safety concerns, and private sector migration, particularly among psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses. Better tracking and policy reforms are needed to address these issues. (Dean, Chapman)

Retention of the current workforce was another key focus, with Ratzliff stressing the need to enhance compensation, improve work environments, and address personal factors that influence workforce stability. She emphasized that addressing these issues is crucial for making the behavioral health care field sustainable and rewarding. Her remarks set the stage for the panelists to explore these topics focusing on practical solutions for addressing workforce challenges.

SYSTEMIC INTEGRATED CARE: RESPONDING TO BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL HEALTH CARE NEEDS

Susan McDaniel, the Laurie Sands Distinguished Professor of Families and Health at the University of Rochester Medical Center, began by pointing out that most people who receive mental health services first seek care from primary care clinicians. She said services that integrate behavioral health and primary care allow for early intervention for patients with the most common chronic illnesses that frequently include comorbid mental health problems. McDaniel added that integrated care is an effective biopsychosocial approach that recognizes the indivisibility of mental and physical health issues and improves access to care. It also allows for behavioral health care clinicians to see patients that they would not otherwise see in a mental health clinic.

McDaniel focused on discussing the dynamics of team-based care by first outlining the theoretical foundation of the biopsychosocial model, developed by George Engel at the University of Rochester (Engel, 1977). This model posits that understanding a patient’s health involves more than just biological factors; it also encompasses psychological and social elements. McDaniel traced the evolution of this model within clinical settings, emphasizing its role in pioneering a more holistic approach to patient care that transcends the traditional medical model focused solely on physical ailments. She described how the University of Rochester has implemented integrated care for 39 years as the method to achieve a biopsychosocial approach to health care, using as an example primary care and mental health clinicians working as a team to provide collaborative services for patients and families within the rubric of family medicine.

McDaniel elaborated on the training and coordination needed among different health professionals to work effectively as a unit, requiring strong discipline-specific education as well as respectful interprofessional education and training with a shared biopsychosocial mental model. Moving beyond traditional biomedical approaches, she described the barriers to adopting integrated care models, including resistance to change within established health care systems and the need for interprofessional team training to support effective teamwork. She also argued that, to implement integrated primary and specialty care within health systems, systemic awareness is necessary. The field of implementation science, she said, emphasizes the importance of analyzing organizational “readiness to change.” Training is needed to interrupt the old way of doing things because “the same old thinking results in the same old results.” Based on adoption of the biopsychosocial systems approach, she said that a shared systemic mental model and a “habit” of collaborating across disciplines is part of a biopsychosocial solution.

Given the huge effect of behavior on health outcomes, McDaniel called for a broader paradigm shift in health care toward models that fully embrace

the biopsychosocial approach. She urged health care policy makers, hospital leaders, educators, and health care professionals to consider systemic changes that support integrating behavioral health into all aspects of health care.

REFRAMING DISTRESS: WHY MORAL INJURY MATTERS

Wendy Dean, the founder of Moral Injury of Healthcare, focused on the psychological impact of ethical challenges that health care providers face in the system, which she argued lead to moral injury and severely affect the well-being of clinicians and the quality of care they provide. Dean began by defining moral injury as the distress that results from actions, or the lack of actions, that violate one’s ethical or moral code. Unlike burnout, which is often caused by excessive workload and administrative burdens, moral injury is tied directly to the ethical environment and the constraints that prevent clinicians from providing the best care possible, she said.

She detailed the systemic causes of moral injury in health care, including the conflicts between profit-driven health care models and patient-centered care. Dean emphasized how current health care systems often put clinicians in impossible situations, where they are forced to make decisions that compromise ethical standards due to external pressures, such as time constraints, resource limitations, and conflicting policies. She shared a descriptive framework developed by the Workplace Change Collaborative1 and sponsored by HRSA, that details the drivers, processes, and outcomes associated with moral injury.2 The framework also identifies practical strategies and tools to improve worker and learner well-being in health and public safety settings.

Dean discussed the profound impacts of moral injury, including emotional exhaustion, reduced job satisfaction, and high turnover rates. She highlighted that these impacts are not only detrimental to the clinicians themselves but also adversely affect patient care quality and safety. Throughout her presentation, Dean advocated for systemic changes to address moral injury. Starting with hospital leaders, she called for health care systems to reevaluate and realign their operational priorities with core clinical values. This includes promoting policies that support ethical practice, improving the work environment, and ensuring that clinicians have adequate resources to offer the best care. She also advocated for training the existing workforce so they have a framework and structure for managing the issues and training the next generation of the workforce (currently in school) so they will also have the tools to effectively engage in the environment in which they will be working.

Dean also underscored the importance of research on moral injury to

___________________

1 See https://www.wpchange.org/ (accessed September 21, 2024).

2 See www.fixmoralinjury.org (accessed September 16, 2024).

better understand its causes and effects. She highlighted her organization’s role in educating health care professionals about moral injury through workshops, seminars, and sharing resources that help individuals and organizations recognize and mitigate these issues. Dean stressed the need for a cultural shift within health care institutions to prioritize ethical practices and support clinicians. She called on health care leaders to improve the overall health of both clinicians and patients by taking decisive action to mitigate the conditions that lead to moral injury. She urged all workshop participants to heed the advice of Don Berwick, former administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and head of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, “when you are feeling hopeless, act.”3

RE-ENVISIONING THE BEHAVIORAL HEALTH WORKFORCE WITH A FOCUS ON UNDERSERVED COMMUNITIES

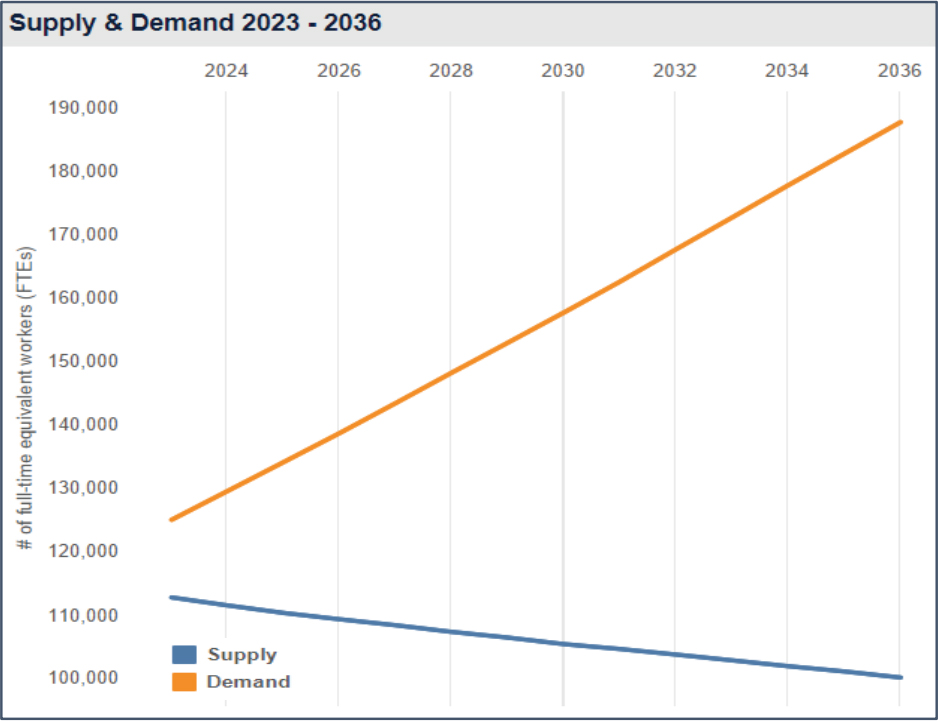

Larke Huang, senior advisor in the Office of the Assistant Secretary and Director of the Office of Behavioral Health Equity at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), discussed advancing behavioral health equity and addressing the systemic barriers that contribute to care disparities. She highlighted the strain on the behavioral health system, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which widened the gap between supply and demand. She said an increasing mismatch of supply and demand across all health care occupations is projected and is expected to continue growing through 2036 (HRSA, 2024c) (see Figure 2).

She noted significant disparities in care access and quality for underserved communities, outlining four key barriers:

- A lack of concordance between patients and clinicians in racial, ethnic, linguistic, and cultural identities;

- A lack of racial diversity among licensed specialists;

- Limited availability of clinicians who speak languages other than English (or are trained in using language interpreters); and

- Insufficient infrastructure to recruit and retain students of color in the behavioral health workforce.

Huang referred to the “leaky pipelines” in workforce development, where many individuals from underserved communities do not complete the licensing process despite having obtained formal education and training. She reported that SAMHSA is working to address these gaps through scholarships

___________________

3 See https://www.iheart.com/podcast/269-moral-matters-74692424/episode/feeling-helpless-take-action-l-s1-74733947/ (accessed October 10, 2024).

SOURCES: Presented by Larke Huang on July 10, 2024; HRSA, 2024c.

and the minority fellowship program,4 although Black and Hispanic social workers who receive their training at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and Hispanic-serving institutions (HSIs) of higher learning that do not receive funding from SAMHSA are missing these opportunities.

Huang discussed several initiatives aimed at improving behavioral health equity, including a SAMHSA technical experts panel on workforce. This panel, which convened professionals from various fields, professional associations, national associations, payers, community-based organizations and nontraditional community providers, among others, focused on a range of workforce challenges, including the use of nontraditional workers, such as peers and community health workers; career paths; and infrastructure support, such as policy, data, and financing. As part of the panel process, SAMHSA heard from states and communities about innovative projects on workforce issues and is developing a web-based database to track community-based innovations and workforce projects at the state level.

Huang also highlighted community-initiated care models that leverage trusted local resources. One example is the Confess Project,5 a barber shop–led initiative where barbers are trained in mental health first aid. Some evalua-

___________________

4 See https://www.samhsa.gov/minority-fellowship-program (accessed September 21, 2024).

5 See https://www.theconfessprojectofamerica.org/ (accessed September 17, 2024).

tion data are available and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are in process. Another is the Friendship Bench,6 a community-based cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) program where grandmothers provide support. She also mentioned faith-based models in various cultures (such as Black and Korean churches) that deliver “wraparound” services to communities in need.

Huang acknowledged ongoing challenges in fully realizing behavioral health equity, including funding constraints and the need for comprehensive data to address disparities. She emphasized the importance of continued innovation, research, and policy advocacy to ensure behavioral health systems are equitable and responsive to all populations. She noted that SAMHSA will continue to prioritize workforce issues, planning further interventions and initiatives in the coming years.

CHALLENGES ACROSS THE BEHAVIORAL HEALTH CONTINUUM

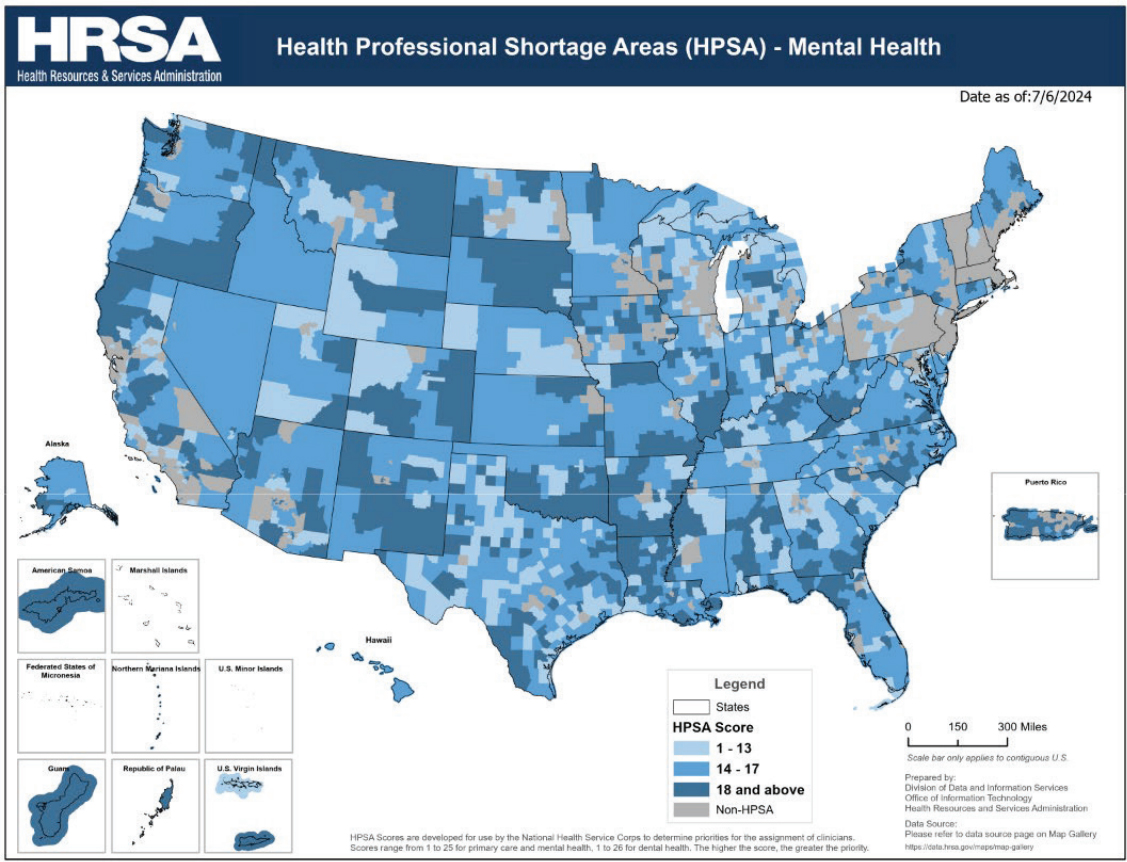

Susan Chapman, professor in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, outlined significant workforce challenges that impact the delivery of behavioral health services, emphasizing areas with persistent shortages. She highlighted the Health Professional Shortage Areas; the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) uses a scoring system to determine the extent of workforce shortages across various regions (see Figure 3). These scores impact funding, workforce stipends, and loan repayment programs, enabling strategic planning and resource allocation to address these gaps. Workforce challenges include a critical shortage of trained professionals in many areas, inadequate training for current demands, and regulatory hurdles that complicate the scope of practice and licensure.

Chapman emphasized the importance of expanding the scope of practice for various nursing professionals, including Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs), a category that includes nurse practitioners (NPs) trained and certified in mental health. Those NPs include Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioners, Family Nurse Practitioners, and Clinical Nurse Specialists (in some states). APRNs that have prescriptive authority can independently treat mental illness in many states, thus contributing to addressing workforce shortages. She described a four-state (Oregon, Colorado, Massachusetts and Illinois) scope-of-practice study she and her colleagues had conducted (Chapman et al., 2019). Those states were chosen because they had different scopes of practice for prescribing. In the “full-authority” states, practitioners had more freedom to develop nursing-based models of care (such as multigroup

___________________

6 See https://thefriendshipbench.org/ (accessed September 17, 2024).

SOURCES: Presented by Susan Chapman on July 10, 2024; HRSA, 2024a.

practices of only NPs). They also had more ability to join panels for multiple types of payers and had more NPs in leadership positions. Overall, she said that the field’s understanding of NP capability to fill unmet needs in the behavioral health workforce is mixed because of the differences across states in licensure and regulation. As an example of how NPs could be deployed to address a behavioral health crisis, she described her own recent study on NP engagement in prescribing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (Chapman et al., 2024). Over time, the NP population has been steadily increasing, as has the ability to obtain Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) registration to prescribe medications for opioid use disorders.

Chapman discussed the role of peer support specialists in the behavioral health workforce and how individuals with lived experience with mental health or substance use disorders bring unique perspectives and capabilities. Chapman mentioned a review that she and her colleagues at the University of Michigan Behavioral Health Workforce Center conducted on 23 journal articles (Gaiser et al., 2021); peers were employed in different settings, including the VA, hospitals, and community centers. She noted that 14 of those studies observed significantly improved clinical outcomes in participants’ social functioning, quality of life, patient activation, and behavioral health. Chapman pointed out that while these roles are expanding, challenges stand in the way of fuller integration into the workforce. For example, a lack of training and

certification (when it is tied to billing in some states), low wages (that may be intentional in some cases, to protect people with lived experience from losing disability benefits, but nevertheless makes it difficult for others to earn a living wage), and stigma that may prevent full integration into treatment teams.

Chapman called for policy reforms that support expanding the workforce through enhanced training programs, better compensation models, and regulatory changes that allow for greater flexibility in professional roles and practices. She also called for systemic changes to better support the workforce, including increased funding for development, and noted the continued structural barriers and stigma that prevent full integration of peer providers.

THE PHARMACY DEPARTMENT’S ROLE IN MENTAL HEALTH MANAGEMENT: AN FQHC CASE STUDY

Thomas Bateman, lead clinical pharmacist at the Henry J. Austin Health Center and clinical assistant professor at Rutgers, presented an overview of the integration of clinical pharmacy services into primary care, particularly within an FQHC. His presentation focused on the critical role of clinical pharmacists in addressing behavioral health challenges, particularly within underserved urban communities, and provided insights into how pharmacists can be effectively integrated into the behavioral health care team to improve patient outcomes.

Noting that pharmacy services can vary widely across FHQCs, Bateman described the structure at his center as composed of three pillars: a dispensing pharmacy, the drug pricing program of Section 340B of the Public Health Service Act,7 and the clinical pharmacy service, which is embedded into the health center and offers one-on-one visits.8 He said that this integrated care model is particularly beneficial for managing chronic diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, which often coexist with mental health disorders. Bateman emphasized that pharmacists’ expertise in medication management not only enhances the quality of care but also leads to better health outcomes for patients with complex needs.

Bateman described how the center began to integrate clinical pharmacists at the practice site; it started with a grant-funded RCT. The original project looked at diabetes and focused on the clinical outcome of the hemoglobin HbA1c measure of long-term blood-sugar control. The results identified two cohorts of patients within the study: one group with depressive symptoms and the other group without. The group with depression and diabetes had a much

___________________

7 See https://www.hrsa.gov/opa (accessed September 21, 2024).

8 A one-on-one pharmacy visit is a private consultation with a pharmacist where you can ask questions, share concerns, and get advice.

greater improvement in HbA1c levels in the pharmacy intervention group, showing that pharmacists working directly with the patient in addition to the primary care physician (PCP) could helped improve medical outcomes compared to care provided by the PCP alone. Medical and mental health findings favored the collaborative model (Bateman et al., 2023; Wagner et al., 2022). This led to a nonrandomized study of chronic medication management for four disease states—including anxiety and depression. For each disease state, they saw improvements in clinical measures compared to baseline (McCarthy and Bateman, 2022; Pastakia et al., 2022). (The wrap-up of that project coincided with the onset of the pandemic, and the center switched to telehealth services, including pharmacy visits, increasing pharmacists’ productivity.)

Center pharmacists are focused on providing psychiatric medication management. For example, they have instituted a weekly meeting of the entire behavioral health department—with clinical pharmacists—to determine whether individual patients should be linked to a pharmacist and/or have a higher level of care. They also employ a psychiatric pharmacy resident to proactively manage the care of patients receiving psychiatric medications. Bateman discussed the challenges and successes of this model, noting that despite the high demand for services and limited resources, the center has successfully implemented strategies that use the full scope of pharmacists’ expertise. He said, this has been particularly impactful in improving medication adherence and providing comprehensive, patient-centered care. He indicated that payment models are one of the biggest challenges for clinical pharmacy, saying, “We are not recognized as providers” for reimbursement. Until that changes, he added, chronic care management may be the one way that pharmacists within FQHCs can generate revenue.

DISCUSSION

Ratzliff started a discussion about the roles, certifications, and challenges for prevention specialists, particularly in the primary care setting. McDaniel emphasized the importance of primary care focusing on prevention and early intervention to avoid more severe health issues. She highlighted the roles of various primary care team members, including peers, medical assistants, community health workers, nurses, NPs, and PCP, all of whom can contribute to preventive care.

A question arose about the specific roles of prevention specialists outside of health care settings, such as in schools and communities. Huang responded by acknowledging that although trained preventionists and evidence-based interventions exist, integrating these into health care, school, and community settings needs greater focus. She mentioned that this would require clearly defining roles, figuring out payment structures, and focusing on population-

wide interventions. Bateman brought up the need for specific protocols for managing the care of patients with suicidal ideation in primary care. He detailed the structured protocols at his center, including systematically screening for high-risk patients using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9.9

To include preventive care as a fundamental component, Ratzliff suggested that training should shift toward managing population health proactively, not just treating individuals who seek care. This would involve training clinicians to think of themselves as responsible for the health of all patients, regardless of whether they present for care.

One participant asked where the field was losing the most behavioral health care providers, in terms of professions and settings, and what data tracking was needed to better understand this problem. Dean explained that psychiatrists tend to go into private practice because it is hard to match practice and education costs in other care settings, and many do not accept insurance, which exacerbates access issues. She also shared the challenges of retaining residential staff due to low wages (equivalent to fast food service). She emphasized the need for policy reform to sustain and retain the workforce. Chapman added that data on attrition are limited, especially at the federal level. For psychiatric nurses, low pay and safety concerns, particularly related to workplace violence, are major factors. She reiterated the need for better tracking and understanding of retention issues.

Another participant asked about resilience. McDaniel emphasized that it is critical for behavioral change and workforce morale. She stated that recognizing strengths, even in difficult cases, is key to supporting workers. Ratzliff added that workforce supervision and support have been neglected, which hinders building resilience. Huang noted that growth opportunities and good supervision are associated with greater retention and emphasized the importance of capitalizing on the strengths of communities and peers.

Another participant asked about pressure points in the system where advocacy and action could have the most impact for change. Dean referred participants to resources like wpchange.org for a comprehensive discussion on the key areas for advocacy and system change. A participant shared that her colleagues are leaving organizations because productivity is prioritized over care quality and asked what levers exist to regulate these demands in a way that ensures adequate care. Dean said that no strong levers currently exist to manage that balance. She mentioned unionization as one approach but stressed the need for policy reforms that define reasonable workloads to protect both patients and clinicians.

___________________

9 See https://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/patient-health (accessed September 24, 2024).

This page intentionally left blank.