Addressing Workforce Challenges Across the Behavioral Health Continuum of Care: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: Session 6: Innovations, Technology, and Measurement

Session 6

Innovations, Technology, and Measurement

Session 6 aimed to underscore the transformative potential of innovation, technology, and measurement in the behavioral health sector. Speakers discussed leveraging digital tools, data-driven approaches, and new care models, the workforce can improve care access, enhance service quality, and achieve better patient outcomes. Challenges were also discussed and included barriers related to implementation, data integration, privacy, and equity. Speaker highlights are outlined in Box 7.

Patricia Pittman, professor of Health Policy and Management at the George Washington University and the director of the Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity, moderated Session 6 and opened by emphasizing the importance of taking a broad, systemic view of the behavioral health workforce. She highlighted the need to understand the workforce not just in terms of supply but through multiple dimensions. She noted a tendency during the workshop to move between the more microlevel conversations about different models and the more macrolevel conversations about the levers that are available to strengthen the health care workforce and sort out what the whole should look like.

Pittman introduced the concept of “health workforce equity,” which she defined as a diverse workforce that has the competencies (skills), opportunities (within system constraints and facilitators), and courage (personal motivation) to provide patients with a fair opportunity to attain full health potential.

She emphasized that achieving workforce equity requires attention to six key domains:

Box 7

Highlights from Individual Workshop Participants in Session 6

- Achieving workforce equity requires addressing who enters the workforce, how they are trained, and under what conditions they work, ensuring that diverse professionals can meet the needs of underserved populations. (Pittman)

- Traditional workforce models often fail to capture the complexity of behavioral health service delivery, with a need for improved measurement tools that better align care providers with patient needs. (Glied)

- Network adequacy should be measured not solely by counting health care providers but by assessing whether patients can access services and receive follow-up care. Developing new metrics to measure provider use and outcomes is essential. (Glied)

- Telemedicine, teleconsultation, and expanding the roles of peers and community health workers can address geographic disparities and improve access to services. (Glied)

- AI can enhance the quality of mental health care by improving training and ensuring therapists consistently apply empathic techniques and evidence-based practices. AI tools can support therapists with feedback and ongoing skill development. (Imel)

- Digital mental health treatments, including mobile- and Internet-based tools, are increasingly used as frontline interventions for conditions such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD. However, only a small fraction of these tools have robust evidence demonstrating their efficacy. (Schueller)

- Frameworks are needed to evaluate digital mental health tools, including the safety, efficacy, and usability, to ensure they are effectively integrated into clinical care pathways. (Schueller)

- Who enters the workforce?—diversity and overall supply,

- How are they trained?—training aligned with both skill sets and social missions,

- What is the distribution of the workforce?—geographic and specialty distribution,

- Whom do they serve?—including Medicaid enrollees and the uninsured,

- How do they practice?—work models and practices, and

- Under what conditions do they work?—including compensation and safety.

Pittman discussed the importance of using these domains for not only planning purposes but also evaluating the effectiveness of workforce policies and programs.

INNOVATION, TECHNOLOGY, AND MEASUREMENT IN THE BEHAVIORAL HEALTH WORKFORCE

Sherry Glied, dean of the New York University Robert F. Wagner School of Public Health and former assistant secretary at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, opened by challenging the traditional models used to estimate workforce needs, which often rely on simplified equations that fail to capture the complexity of behavioral health service delivery. She illustrated this by comparing the typical workforce planning models and the actual variability in service use, which cannot be fully explained by simple mathematical equations.

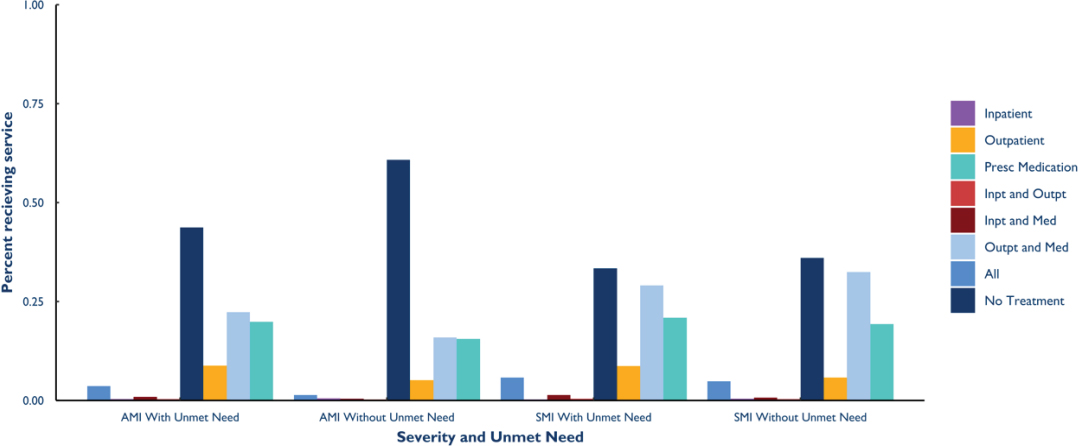

She highlighted traditional approaches to estimate workforce needs—based on population size, incidence of conditions, and service intensity—often overlook the variability in how services are used (see Figure 5). For example, she noted that if workforce planning were solely based on these models, the United States would appear to have an adequate number of behavioral health care providers. However, there are significant gaps in service provision and access.

She also argued that to better understand and address these gaps, more sophisticated measurement tools are needed that account for the nuances of behavioral health service delivery. She said that analysis of data from the Medical Expenditure Survey reveals that many individuals use such services only sporadically or not at all. A quarter of people who initiate services only have a single visit, and most have only a few visits. She also noted the high variability between provider type and visit frequency, with counselors seeing clients more regularly than licensed professionals, such as psychologists or primary care clinicians.

She highlighted the significant geographic disparities in the distribution of behavioral health care providers relative to areas of high need, particularly in regions like Appalachia and the Deep South. Additionally, the introduction of new types of care providers, such as NPs for prescribing medications, has shifted the landscape of care. However, the hours worked by therapists have remained low, with psychologists working relatively fewer hours than other health care providers, leaving room for potential expansion.

NOTE: AMI = any mental illness; SMI = severe mental illness; Presc = prescription; inpt = inpatient; outpt = outpatient; med = medication.

SOURCES: Presented by Sherry Glied on July 11, 2024.

She said the central problem in the workforce is the mismatch between the available care providers and the patients who need care. The system does not adequately match the type of treatment required by the patient with the appropriate care provider. Clear evidence is also lacking about which care providers should treat specific conditions, adding to this challenge.

Summarizing the implications of the data she presented on the mismatch between the existing workforce and the care need, Glied asked three broad questions:

- Which care providers can treat SMI by prescribing medications, and which care providers can provide counseling to people with episodic anxiety?

- What is the least costly way to generate additional care providers for these tasks at the national level?

- What is the most efficient way to deliver these tasks at the local level?

She said that focusing on that mismatch is going to be key to addressing the workforce problem.

Glied described workforce innovations that she suggested might allow those who are already trained to provide more services at the margin. Telehealth could increase access to care at nontraditional hours, addressing temporal access barriers, improving service delivery, and expanding the roles of peers and community health workers to meet demand, with the proviso that it would be important to carefully assess where to best contribute within the broader continuum of care. Glied said more flexible telehealth payment policies are needed in Medicare and Medicaid to encourage remote services to address both geographic and temporal barriers.

She also noted that current measures of network adequacy, which count health care providers rather than assessing whether new patients can access care, are insufficient. She said that no existing CMS quality measures can achieve this goal, so new measures of use and outcomes should be developed from sources such as insurer administrative data. She also advocated for developing new measures that address questions such as the share of spending on behavioral health, number of health care providers in the network who billed the plan five times or more in the prior year, percentage of patients who see a provider in a fourth visit (an industry standard), and number of care providers who billed last year but not this year (are care providers in the network seeing patients?). She also suggested rethinking how unmet need is measured. Instead of relying solely on self-reported data, Glied suggested examining the impact of unmet needs on health outcomes, such as emergency visits, hospitalizations, and suicide attempts.

USING AI TO IMPROVE CARE QUALITY FOR MENTAL HEALTH AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

Zac Imel, professor in the counseling psychology program at University of Utah, focused on the potential of AI to enhance the quality of mental health care by improving training and ensuring consistent application of therapeutic skills across large populations. His work addresses a fundamental challenge in mental health care: how to ensure that once individuals gain access to a therapist, the care they receive is high quality and truly beneficial.

Imel began by discussing the importance of empathy in therapeutic settings, noting that empathy is a foundational aspect of effective mental health care. Despite its importance, ensuring that therapists consistently apply empathic communication can be challenging, especially considering the sheer volume of therapy sessions each year. He emphasized that, although empathy can be a “fuzzy” concept, it is measurable. Psychologists have developed reliable methods to assess it during therapy sessions, such as identifying instances of complex reflections and other empathic responses. However, scaling this measurement across millions of sessions annually is a significant challenge. Among the challenges, he argued, is that traditional training methods, which often involve workshops followed by immediate application in the field, do not always lead to sustained skill development. Imel pointed out that this gap between training and application often results in therapists not consistently applying the skills they were trained to use.

To address these challenges, Imel’s team has been developing AI tools that can assist in training and evaluating therapists on a large scale. They use machine learning algorithms to analyze session transcripts and assess the extent to which therapists are employing empathic techniques and other evidence-based practices. One tool he showcased allows therapists to practice specific skills, such as open-ended questions or psychoeducation, with immediate AI feedback. He also provided examples of how AI tools can help therapists improve skills through repeated practice and feedback. For instance, a therapist might practice behavioral activation techniques with a virtual patient, receiving feedback and adjusting in real time.

Imel concluded by discussing the broader implications of integrating AI into mental health care. Despite the common concern that AI might replace human therapists, he argued that its real potential lies in augmenting human capabilities, particularly in training and quality assurance. He said that by using AI to support ongoing skill development, the mental health workforce can become more effective in delivering evidence-based care. He also noted that continued research is needed to refine these AI tools and ensure they are effectively integrated into mental health care systems. He stressed the impor-

tance of collaboration among technology developers, clinicians, and researchers to create AI solutions that enhance the quality of care.

INTEGRATING DIGITAL MENTAL HEALTH TOOLS IN THE BEHAVIORAL HEALTH CONTINUUM OF CARE

Stephen Schueller, professor of psychological science and informatics at the University of California, Irvine, addressed the integration of digital mental health tools into the behavioral health continuum of care, emphasizing the state of the evidence, evaluation considerations, and practical aspects of implementing these tools in various care pathways. Schueller began by asserting that digital mental health is no longer a future concept but a current reality. He highlighted the significant investment and development in digital mental health treatments over the past 2 decades, with billions of dollars invested in this area. These technologies, including Internet- and mobile-based interventions, are now being used as frontline interventions in various parts of the world, such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and Germany.

Schueller introduced the concept of digital mental health treatments as technology-enabled services, which involve a blend of technological features and human support. He said this model is particularly effective for individuals with higher levels of symptom severity, where guided interventions with human support are more beneficial. He presented evidence from RCTs demonstrating the efficacy of some digital mental health treatments for conditions such as depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, and sleep disorders. He argued that these interventions have shown reliable and robust effect sizes, supporting their use as evidence-based treatments. However, he also emphasized using appropriate methods for the evaluation of digital mental health treatments, such as matching the appropriate interventions to specific use cases. He highlighted the need for frameworks to evaluate the effectiveness, safety, and usability of these tools before they are integrated into care pathways.

He also emphasized the importance of understanding market segmentation in digital mental health. He noted that different populations have varying needs and preferences for care. He argued that the behavioral health system needs to align its offerings with these demands to maximize engagement and effectiveness.

Despite the potential of digital mental health treatments, Schueller acknowledged the challenges, particularly the proliferation of tools with varying levels of evidence. He noted that while thousands of digital mental health products exist, few have strong evidence of efficacy, and some may even cause harm. Another significant challenge is the lack of clear reimbursement models. Schueller advocated for evidence standards and frameworks to create

digital formularies, aiding both decision making and reimbursement. He also discussed the importance of effectively integrating digital mental health tools into existing care pathways, which requires careful consideration of how these tools complement human-delivered services and can be used to address gaps in care, particularly for underserved populations.

Schueller reiterated that digital mental health is a vital component of the behavioral health continuum of care. He emphasized the need for ongoing research, development of evidence standards, and thoughtful integration of these tools into clinical practice. He argued that by leveraging digital mental health treatments, the workforce can expand its reach, improve care delivery, and better meet the diverse needs of the population.

DISCUSSION

A participant asked about the specific challenges in measuring behavioral health outcomes and who should be responsible for developing these measures. Glied noted the different sources of measurement and said CMS has focused on ensuring network adequacy in contracting for managed care plans under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). She suggested that HRSA, with its focus in workforce issues, should collaborate with CMS in this effort. Pittman noted, however, that researchers face increased difficulty in accessing Medicare and Medicaid data. She also noted that the Healthcare Workforce Commission, a provision of the ACA, might have taken on this responsibility if it had been funded.

Another participant raised concerns about the risks of technology and commercialization. Schueller responded that while some patients may be concerned about interacting with technology, others prefer it, and he encouraged participants to think of digital technologies as part of a care pathway and not a replacement for treatment services with care providers.