Cybercrime Classification and Measurement (2025)

Chapter: Summary

Summary

Cybercrime poses serious threats and financial costs to individuals and businesses in the United States and worldwide. Reports of data breaches and ransomware attacks on governments and businesses have become common, as have incidents of identity theft and online stalking and harassment against individuals. Concern over cybercrime has increased as the internet has become a ubiquitous part of modern life. However, the U.S. national crime statistics system has limited coverage of cybercrime, and existing measurement and data efforts to track such crimes are fragmented and hampered by challenges such as underreporting, the variable scope and nature of incidents, and the rapidly evolving nature of technology.

In response to these issues, two recent laws directly call for the addition of cybercrime content to current U.S. national crime statistics. Both of these laws—cybercrime provisions in the Violence Against Women Act Reauthorization Act of 2022 (P.L. 117-103) and the Better Cybercrime Metrics Act (BCMA; P.L. 117-116)1—require the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to add a category for cybercrime and cyber-enabled crime to the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), the compilation of crime incident reports from thousands of state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) law enforcement agencies. The BCMA expanded the focus

___________________

1 See 136 Stat. 950 in P.L. 117-103 in particular, as P.L. 117-103 is the sprawling omnibus appropriations act for fiscal year 2002 into which numerous other bills were folded, including both the Violence Against Women Act Reauthorization Act and the Cyber Incident Reporting for Critical Infrastructure Act that is also a major focus in this study; both cybercrime reporting provisions are reprinted in Appendix A.

to cybercrimes against both individuals and businesses (rather than only individuals) and further directed the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) to add cybercrime questions to the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), the household survey that provides information on victimization incidents against individuals regardless of whether they were reported to police.

The BCMA also directed the U.S. Department of Justice to enter into an agreement with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) to convene this Panel on Cybercrime Classification and Measurement, which it did through the FBI. The charge to the panel, shown in Chapter 1, was to develop a taxonomy to facilitate improved collection of cybercrime data in the nation’s crime statistics system. In this task and in many important respects, our study is a direct extension of the predecessor Panel on Modernizing the Nation’s Crime Statistics (hereafter, MNCS panel; National Academies, 2016a, 2018) that was jointly sponsored by the BJS and the FBI.

THE CHALLENGES OF CLASSIFYING AND MEASURING CYBERCRIME

A U.S. Government Accountability Office (2023; USGAO) review described an exceedingly decentralized web of at least 13 federal agencies with some responsibility for gathering information on cybercrime, including those tasked with the identification, investigation, and prosecution of cybercrime activity. The USGAO’s overview of this data-collection terrain suggested wide variety in the manner, extent, and capability of these agencies to track cybercrime. Importantly, the review identified fundamental challenges to cybercrime data collection, among them the lack of common, consistent definitions of cybercrime; the lack of any integrative mechanism to combine and analyze results; and the lack of incentive among cybercrime victims to report incidents. In approaching our statement of task, we first described basic precepts guiding our work, focusing on the fit of “cybercrime” within the existing national crime statistics apparatus. One such precept is stated as a formal conclusion to motivate the work: the nature of cybercrime makes it inherently difficult to fit within the current national crime statistics system. For example, the “cyber” component of cybercrime offenses could be characterized as the victim, offender, modus operandi, location, motive, or weapon used in the offense logged in U.S. crime statistics. Moreover, the boundaries of cybercrime incidents can be difficult to pinpoint relative to the offense types covered in current statistics; data breaches and ransomware attacks can have ripple effects on thousands or millions of individuals, raising the concern of whether it is fair to count the affected data holder as the sole victim.

Conclusion 1-1: Measurement of cybercrime is challenging—particularly in the context of current U.S. national crime statistics—for a number of reasons, including expected underreporting, the variable scope and nature of incidents, and the changing nature of technology.

Two other precepts stem from the interpretation of the word “cybercrime” itself. First, the statement of task obliges us to be “crime”-centric in nature, conceptualizing “cybercrime” as crime with a cyber/computer component rather than as cyberactivity with a criminal component. Practically, this means that the language of federal and state criminal codes remains a necessary anchoring point: an essential part of the definition of crime (and cybercrime) is that it is unlawful behavior rather than simply bad or undesirable behavior. A related precept extends the counterpart cyberactivity-with-criminal-component approach, emphasizing that cybercrime and cybersecurity incidents or breaches are strongly related but not equivalent concepts. Many cybersecurity incidents, being conducted with malicious intent, are indeed cybercrimes, but such incidents may also arise from simple human or technological error or as a direct consequence of environmental/physical factors. Hence, while these concepts overlap significantly, not automatically equating the two is vital.

TREATMENT OF CYBERCRIME IN CURRENT DATA COLLECTIONS

Before developing our taxonomy for measuring cybercrime, we briefly reviewed the ways in which cybercrime and related concepts are measured in existing and developing data systems, with particular eye to the categorization schemes used in those systems.

National Crime Statistics: The National Incident-Based Reporting System and the National Crime Victimization Survey

Although the NIBRS format has been in development and available to SLTT law enforcement agencies since the late 1980s, it only became the centerpiece of the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program in January 2021, following retirement of the previous Summary Reporting System (SRS). Prior to 2021, the SRS provided no mechanism for coding cybercrime in the collection’s core set of offenses known to police.2 Adoption of the NIBRS format greatly expanded the roster of covered offenses including the cybercrime-related offenses of wire fraud and credit card fraud as

___________________

2 It was technically possible to log cybercrime as a type of fraud or as “all other offenses,” but in either case, the reporting was an arrests-only count.

subcategories of fraud; in 2013, NIBRS documentation formally revised the definition of wire fraud to include computers, email, text messages, and related technologies as the delivery mechanism. From NIBRS’s inception, its Data Element 8 has provided a means for indicating computer involvement in any type of crime, asking whether the offender was suspected of using “Computer Equipment” in the crime. In 2015, the UCR Program took three major steps to improving cybercrime coverage, adding two new entries—Hacking/Computer Invasion and Identity Theft—as new crime types and adding Cyberspace as a response option for the location of the offense. However, these two existing indicators in NIBRS have challenges as true markers of cybercrime; the most recent NIBRS user manual documentation has modified the Data Element 8 response to “Computer Equipment (Handheld Devices)” and apparently intends to capture incidences of driving while texting, while the Cyberspace location definition focuses on internet involvement in the offense rather than computer involvement more generally.

The core NCVS, operated by BJS with the U.S. Census Bureau as data-collection agent, is a panel household survey in which an NCVS-2 Crime Incident Report interview is conducted for each victimization incident reported during the preceding six months, as elicited through the NCVS-1 Basic Screen Questionnaire. Historically, the NCVS has largely mirrored the definitions and concepts used in the UCR Program, precisely to estimate the extent of crime that is not reported to police through comparison with the UCR’s police report numbers. Accordingly, core NCVS content largely mirrors the street crime/interpersonal crime focus of the historical UCR SRS and thus lacks obvious connection to cybercrime. However, the NCVS has long expanded its substantive reach through periodic fielding of supplemental questionnaires, which may be administered even if the household has no traditional violent crime to report. Over the years, NCVS supplements have permitted the survey program to touch on aspects of cybercrime: identity theft and fraud through the Identity Theft Supplement and Supplemental Fraud Survey, cyberstalking through the Supplemental Victimization Survey, and cyberbullying through the School Crime Supplement.

Other Entities Collecting Cybercrime-Related Data, Particularly Fraud

The FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), originally founded as the Internet Fraud Complaint Center, has the primary function of serving as a public front door to report internet-facilitated crimes. Though numerous variants of fraud dominate the listings in IC3’s reports, other cybercrime types including ransomware, crimes against children, and harassment/stalking are reported to the IC3 by the public. As with the NIBRS, there is no underlying taxonomic structure to the IC3’s list of covered offenses,

save that the list is revised slightly from year to year based on increasing or decreasing frequency of particular offenses. Similarly, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) populates its Consumer Sentinel Network database based on reports from the public through its online portal. While the IC3 has expanded its scope to include other types of cybercrime, the FTC’s collection remains focused on fraud, currently including 20 main categories and 47 subcategories. Its internal categorizations specific to fraud are based principally on the object of value targeted by the fraud, but the categories are not generally filtered or constrained to focus on cybercrime.

Collection of Cybersecurity Incident Information and Cybercrime-Related Information from Business and Industry

Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs) and Information Sharing and Analysis Organizations (ISAOs) are nonprofit organizations intended to serve as trusted entities for information sharing on cybersecurity and cyberthreats. ISACs are specific to particular business/industry sectors falling under the general heading of critical infrastructure, while ISAOs are more flexible in their membership. The National Cyber-Forensics and Training Alliance (NCFTA) performs a similar function of bridging private industry and domestic/international law enforcement partners to foster a trusted, neutral environment for collaboration, with the incentive of working toward shared solutions. For purposes of this study, ISACs/ISAOs and the NCFTA provide useful models for promoting a culture of information sharing across industry and government, even though data products are not yet a part of their role.

The Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR) is an annual report series, compiled since 2008 by Verizon Business and its Verizon Threat Research Advisory Center team, based on the voluntary submission of cybersecurity incident data from an evolving set of contributors. Data for the DBIR exist in a specific coding schema known as the Vocabulary for Event Recording and Incident Sharing (VERIS) which—though not a classic hierarchically structured taxonomy—provides a structured way of deconstructing cybersecurity events along four dimensions: Assets, Attributes, Actors, and Actions. Of these, VERIS’s list of threat Actions is closest to a cybercrime classification scheme, containing five varieties that are highly relevant: Malware, Hacking, Social Engineering, Misuse of Assets, and Physical Actions.

Emerging Collections of Cybersecurity and Cybercrime-Related Incidents

The reporting of major cybersecurity incidents—many of which may be cybercrimes—is currently in a state of major change. The Cybersecurity and

Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) is in the final stages of promulgating a rule, mandated by the Cyber Incident Reporting for Critical Infrastructure Act of 2022 (CIRCIA; P.L. 117-103), that will require a broad swath of businesses in 16 critical infrastructure sectors to file reports on major cybersecurity incidents within 72 hours; such reports to CISA are currently voluntary. The CIRCIA data collection stands to play a considerable role in information collection related to the cybercrime of ransomware, requiring that ransomware payments be reported within 24 hours. The exact list of categories for incidents reportable under CIRCIA is still under development—in late September 2024, CISA issued a draft set of revisions to its standard incident report that borrows Actions and other coding structures from VERIS.

A new rule by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC; 88 F.R. 51896) recently took effect as well, obliging publicly traded companies to disclose major cybersecurity incidents (many of which may constitute cybercrime) within four business days of being deemed a material threat. Thus, while individual CIRCIA reports are meant to be kept confidential by CISA, transparency for the investor public is the driving purpose of the SEC rule.

International Parallels: Cybercrime Data Collection in Canada and the Cyber Classification Compendium

The Canadian UCR Program, administered by a branch of Statistics Canada, shares its acronym with its U.S. counterpart but differs in other respects; police-report statistics are mandatory in Canada, not voluntary, and are commonly extracted directly from the police records management systems (RMS) used by local agencies. Beginning in 2004, the UCR Survey added a two-part Cyber Crime variable to the collection, with both parts premised on the definition of whether a computer (later generalized to refer to information and communication technology broadly) was the target of the offense or the instrument used to commit the offense. The first question asked for a yes/no response as to whether the offense was cybercrime under this definition, and the second question asked which type (i.e., target or instrument) applied. In 2024, the UCR Survey began collecting information using a new classification scheme, expanding the cybercrime type question to include nine response categories—Malware; System and Service Availability; Information Gathering; Intrusion; Data Release (information security compromise); Frauds; Abusive Content; Exploitation, Harassment, or Abuse of a Person; and Uncategorized—drawn from the main headings used in the Cyber Classification Compendium, which is an attempt to create a crosswalk between cybercrime offense types and definitions in international and U.S. law (Wright & Parker, 2023). Because full implementation of the new variable began only recently, its effectiveness remains unknown.

DEVELOPING A TAXONOMY OF CYBERCRIME

In our review of the partitioning and classification of cybercrime, we observed numerous dimensions along which cybercrime offenses might be structured. Notably, these include the degree of cyber/computer involvement and the role of the computer in the offense. Efforts to distill sets of fundamental nature-of-harm groups are also common.

We also reviewed the handling of cybercrime in all-crime taxonomies—notably our predecessor MNCS panel’s classification of crime (National Academies, 2016a) and the International Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2015) on which that classification was based. Both systems define a set of fundamental cyber-specific nature-of-harm categories—unlawful access, unlawful interference, unlawful interception/access of data, and other—to characterize pure cyber-dependent crimes. But both systems rely on coding a base offense and toggling a cybercrime-involvement indicator to construct the vast bulk of cyber-enabled crimes—for instance, extortion plus the cybercrime indicator to connote ransomware or use of the cybercrime indicator to flag computer-related sexual exploitation offenses.

As the MNCS panel did in its reports, we established a set of principles and desired characteristics for our own recommended taxonomy. We sought a taxonomy satisfying all the requirements of a classification for statistical purposes, meaning we aimed to make it exhaustive of all cybercrime, partition it into mutually exclusive categories, and follow a hierarchical structure to the extent possible. We also sought a taxonomy with a small number of main categories, emphasizing the behavior that constitutes an offense without delving into technical jargon or fine-grained categories that may prove unworkable in law enforcement agencies’ RMS specifications. We also sought definitions in the proposed taxonomy that were consistent with but not strictly limited by federal and state law, but also consistent with definitions in existing major collections.

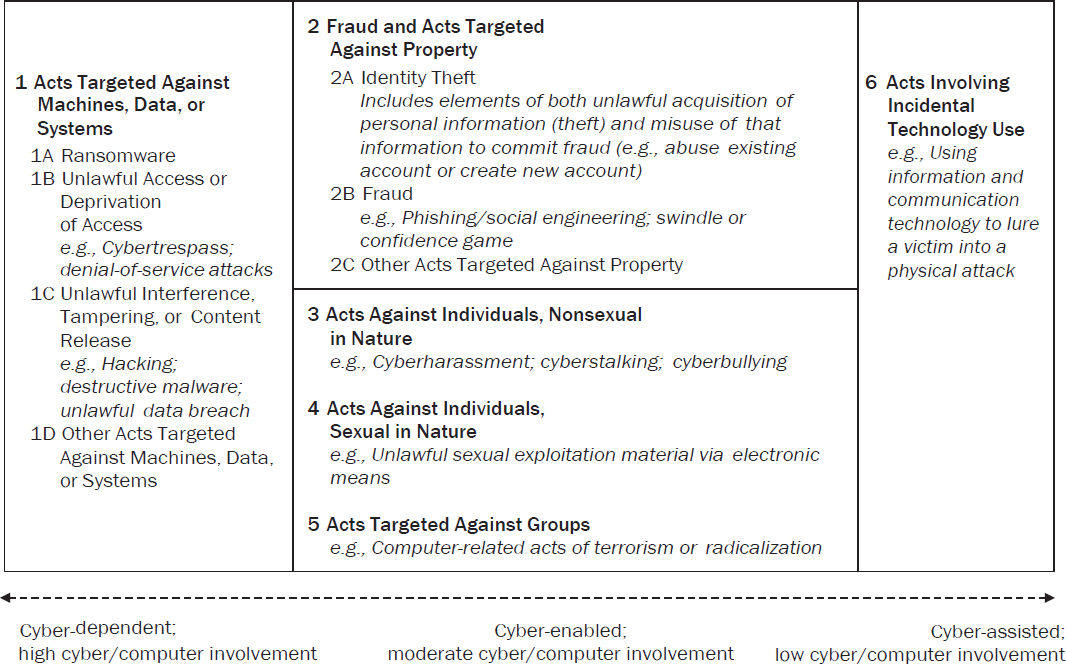

Based on all the preceding, the taxonomy we recommend for cybercrime is given in short form below, expressed graphically in Figure S-1, and articulated in fuller detail in Appendix B.

Recommendation 3-1: The following concise taxonomy should be used as an initial framework for developing statistical measures of cybercrime in the United States:

-

Acts Targeted Against Machines, Data, or Systems

1A Ransomware

1B Unlawful Access or Deprivation of Access

1C Unlawful Interference, Tampering, or Content Release

1D Other Acts Targeted Against Machines, Data, or Systems

-

Fraud and Acts Targeted Against Property

2A Identity Theft

2B Fraud

2C Other Acts Targeted Against Property

- Acts Against Individuals, Nonsexual in Nature

- Acts Against Individuals, Sexual in Nature

- Acts Targeted Against Groups

- Acts Involving Incidental Technology Use

NA Acts with No Cyber/Computer Involvement

Our recommended taxonomy is designed to be exhaustive of the degree of cyber/computer involvement, with main category 1 being pure cyber-dependent crime, categories 2–5 representing moderate levels of cyber-enabling of base crimes, and category 6 representing only cyber/computer involvement (with the final category of no cyber involvement completing the partitioning). Categories 2–5 are structured by the target of the offense, whether property, individual persons, or groups of people. Within major categories 1 and 2, we sparingly delineate specific named offenses, isolating ransomware due to its prominence in public discussion and retaining identity theft for continuity with existing NIBRS and NCVS Identity Theft Supplement usage.

We intend our recommended taxonomy to be actionable and implementable with or without major revision of the underlying classification used for all crime, in the NIBRS or other systems. We concur with the MNCS panel that the nation’s current crime statistics fall short of capturing information on new, important, and emerging types of crime, and we support the aspirational goal of a next-generation NIBRS that can cover a wider array of offense types. Presently, however, we recognize the uniquely delicate and challenging climate for crime and cybercrime data collection, with the NIBRS still contending with the challenges of full implementation, the NCVS beginning to field comprehensively redesigned instruments, and the wide-sweeping mandatory CIRCIA reporting still awaiting issuance of the final rule. Accordingly, our suggestion is to use the recommended taxonomy as an enhanced attribute flag for incidents; in this way, it can add useful information to the NIBRS Hacking/Computer Invasion offense through the disaggregation provided by our category 1, and it can combine with other base offense codes in the NIBRS to cover many cyber-enabled crimes—all without the need for a prior major revamping of code lists.

SOURCE: Panel generated.

Recommendation 3-2: Rather than have a cybercrime classification function as parallel or adjunct to existing crime classifications, the taxonomy presented in Recommendation 3-1 should be implemented in crime data–collection systems as an attribute, flag, or modifier to code incidents in conjunction with the system’s base classification of criminal offenses.

FURTHER RECOMMENDATIONS AND IMPLEMENTATION CHALLENGES

Calibrate Expectations: Cybercrime Estimation as a System-of-Systems

In the panel’s opinion, improvements in cybercrime measurement are definitely possible, but it is important to approach such changes with tempered expectations. Cybercrime’s breadth as a concept and its inherent mismatch with current data-collection practices means that adding a single category to an RMS or a single question to a survey will not suffice. Producing reliable estimates of cybercrime will necessitate a system-of-systems spanning multiple data sources, with each source collecting information on offenses and characteristics of offenses according to its unique strengths. An exact enumeration of cybercrime from any single data resource is unlikely.

Conclusion 4-1: Improving cybercrime measurement is important, but it is equally important that improvements be made with tempered, realistic expectations of the timing and extent of improvement. Cybercrime is an expansive and evolving topic, so it is unlikely that any single statistical source will effectively cover all of its dimensions; analysts will need to make best use of available information from an array of sources to derive markers of cybercrime activity.

Measuring Cybercrime by Leveraging Existing Data-Collection Efforts

Recommendations for the National Incident-Based Reporting System

While we support expansion of NIBRS’s content coverage, we also observe that improved cybercrime collection in the NIBRS is critically dependent on clarification of purpose and intent. Simply adding categories or variables to the NIBRS would be for naught in the absence of clear guidance on how cybercrime is meant to be reported in that system—if individuals or businesses are to be encouraged to report cybercrime incidents to SLTT law enforcement agencies as a matter of good practice and if SLTT agencies, in turn, are to be encouraged to report them in the NIBRS. Accordingly, in the near term, we recommend a series of actions to

take stock of NIBRS’s current cybercrime-related content and establish the conditions for successful implementation of the recommended taxonomy.

Recommendation 4-1: The Federal Bureau of Investigation Uniform Crime Reporting Program should consider the following modifications to the existing National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), preparatory to a more comprehensive cybercrime-collection effort:

- Continue collecting the existing NIBRS offense categories of Hacking/Computer Invasion and Identity Theft, while actively encouraging participating law enforcement agencies to report these offenses;

- Clarify the definition and intended role of the two NIBRS data elements that nominally indicate cybercrime involvement, Data Element 8 with Computer Equipment as response to Offender Suspected of Using and Data Element 9 with Cyberspace as response to Location;

- Consider adding data/systems and digital currency/cryptocurrency as additional intangible property types in Data Element 14 (Type Property Loss/Etc.); and

- Work with the records management system vendor community to ease NIBRS data entry and improve understanding of new elements, and incorporate information and examples associated with these modifications as part of NIBRS data-provider education and training.

This guidance acknowledges that the initial cybercrime categories added to the NIBRS—Hacking/Computer Invasion and Identity Theft—were a reasonable starting position. Hence, rather than requiring that these initial cybercrime categories be fundamentally overhauled up front, we suggest that the intent and objectives of the categories be clarified, and their collection bolstered and promoted as a norm for the NIBRS. Finally, the near-term guidance speaks to the importance of working with RMS vendors; we concur with the MNCS panel that data systems like the NIBRS will be most effective when data submissions are a routine by-product of agencies’ day-to-day use of their own RMS rather than a separate reporting task.

These near-term, preparatory suggestions are meant to ease the way for more fundamental change.

Recommendation 4-2: Following the preparatory steps of Recommendation 4-1, and possibly in conjunction with adoption of a modern classification of crime for statistical purposes, the Federal Bureau of Investigation should incorporate the cybercrime taxonomy in Recommendation 3-1 as a new, mandatory data element in the National

Incident-Based Reporting System Incident Segment. Implementing this new data element may involve consolidating or revising existing computer/cyber-related responses in Data Elements 8 and 9.

Recommendations for the National Crime Victimization Survey and Its Supplements

With respect to the NCVS, our guidance is similar if more pointed in terms of long-term work. The NCVS’s nature as a household survey makes it uniquely suited to generate contextual information about crimes and cybercrimes with a distinctly personal effect. Importantly, the NCVS can suggest explanations about why incidents may not be reported to SLTT law enforcement or other authorities. We suggest that additional periodic supplements to the NCVS could effectively address personal-impact cybercrimes such as phishing/social engineering (as a variant of fraud) and image-based sexual abuse (including cyber-enabled sextortion).

Recommendation 4-3: The Bureau of Justice Statistics should leverage its existing National Crime Victimization Survey supplements with cybercrime-related content (Supplemental Fraud Survey, Identity Theft Supplement, Supplemental Victimization Survey) to contribute to the nation’s understanding of cybercrime. This includes refining the content of those supplements as needed as well as working with data users to facilitate analysis and use of the resulting data, including comparison with other data sources.

Recommendation 4-4: Pending the availability of additional resources for victimization survey work, the Bureau of Justice Statistics should consider increasing the frequency of the three existing cybercrime-related supplements or the fielding of a dedicated cybercrime supplement.

To be very clear on this point, we do not recommend adding cybercrime-related content to the core NCVS, neither as a permanent part of the NCVS-1 Basic Screen Questionnaire nor to the detailed NCVS-2 Crime Incident Report completed for each victimization incident identified in the screener. We believe that the supplemental module approach is better suited for cybercrime-related content than revisions to core NCVS content.

Other Data-Collection Systems

While we do not offer specific targeted recommendations for other data-collection systems beyond the NIBRS and the NCVS, such systems are

potentially part of the system-of-systems approach mentioned previously, and thus we encourage their development and eventual role in comprehensive cybercrime measurement. As the CIRCIA collection nears deployment of a final rule and begins mandatory data collection, it is important to both encourage and evaluate this collection for its potential to provide useful cybercrime information, particularly regarding ransomware; new SEC cybersecurity incident reporting rules warrant similar attention and assessment. Furthermore, as Statistics Canada begins to encourage constituent law enforcement agencies to report data using a detailed list of cybercrime codes, this work should be examined to apply lessons to U.S. NIBRS collection and training.

Aspirational Goals for Cybercrime Measurement

Governance and Coordination of National Cybercrime Statistics

Addressing the lack of an overall governance and coordination structure for crime statistics is a pressing need. Currently, no entity is directly tasked with drawing inference from multiple sources of crime data, and such a structure is arguably even more critical for cybercrime, given the array of public- and private-sector players at work in the field. Thus, we advocate for the creation of an information clearinghouse for cybercrime data.

Conclusion 4-2: As is true of crime statistics in general, the thorough and effective measurement of cybercrime and cyber-enabled crime will remain largely unobtainable absent the development of a governance and coordina-ion process for the collection of cybercrime reports and statistics. Cybercrime measurement is sufficiently fragmented that it is in particularly acute need of an information clearinghouse apparatus, meaning the designation of a specific party or parties to compile the various cybercrime measures that are and will be available and analyze common findings and trends.

It is vitally important that these coordination, governance, and information clearinghouse functions provide overall direction to the cybercrime measurement enterprise. This includes analyzing the full range of public and private data and assessing strengths and weaknesses therein to produce the highest-quality estimates. Additionally, it involves articulating basic rules to ensure accurate data collection (e.g., counting rules for handling multivictim incidents) as well as clarifying the ideal avenue for cybercrime reporting by individuals (i.e., it may be judged most efficient for individuals to report to the IC3 and rely on the IC3 to report data to the NIBRS).

While we note the current absence of information clearinghouse structures and reinforce the need for them, we did not designate specific entities, although the U.S. Office of Management and Budget may be ideally positioned to broker and structure necessary discussions across federal agencies (National Academies, 2018, Recommendation 3.1). The information clearinghouse function for cybercrime may fit within the legally defined mission of the BJS or the stated mission of the IC3 but might also fit into some adaptation of Verizon’s work coordinating cybercrime input from government and industry partners. One reason for declining to formally recommend an entity to perform the coordination and governance functions is that we do not think it appropriate to create the appearance of a major unfunded mandate on any particular agency or organization.

An essential task of any clearinghouse function will be the periodic revision and refinement of applicable definitions, including our recommended taxonomy—the taxonomy we propose is not a static document but rather an initial effort. New category breaks may be suggested by reported data; and taxonomy categories, codes, and examples necessitate periodic review to ensure inclusivity of new/emerging technologies.

Businesses and Organizations as Actors in Crime and Cybercrime Data Collection

Successful cybercrime measurement will rely on the increased and continuing participation of businesses and organizations in reporting cybercrime incidents—a difficult task due to both reluctance of businesses to appear vulnerable and complex liability issues that may arise for some business sectors.

To improve future cybercrime measurement, it will be important to monitor development of the CIRCIA and SEC mandatory-report systems for registering major cybersecurity incidents. Ideally, the CIRCIA collection—with its broad sweep and detailed focus on ransomware incidents—could evolve into a statistical data collection, with resulting data illustrating sector-wise trends and informing responses and interventions to cybercrime attacks. Additionally, major information-sharing vehicles (e.g., the Verizon DBIR series, ISACs and ISAOs, and the NCFTA) could add unique context and empirical insights that could aid the generation of reliable, consistent statistics while helping business effectively navigate the current cyberthreat landscape.

Finally, we propose that a commercial victimization survey may help to provide similar valuable contextual information about offenses not reported to authorities (and the reasons for not reporting) as the NCVS adds to the UCR/NIBRS in the national crime statistics conversation. A survey of businesses’ victimization experiences was part of the original National Crime Survey program, but it was discontinued. The BJS also conducted a

National Computer Security Survey in 2006, but that has not been repeated. General improvements in conducting establishment surveys and, perhaps, increased interest in crime committed against businesses and organizations of all sizes suggest that timing may be ideal to revisit the idea of a commercial victimization survey, with cybercrime as an important component.

Recommendation 4-5: Pending the availability of resources to do so, the Bureau of Justice Statistics and federal agency partners should consider conducting additional rounds of the 2006 National Computer Security Survey, or otherwise field an establishment crime/cybercrime victimization survey, to collect data on crime/cybercrime victimization experiences by businesses and organizations. Such efforts should build on improvements in the conduct of establishment surveys and serve as a complementary marker of cybercrime that is not reported to authorities.

Exploring the Cybercrime and Cybersecurity Nexus

As cybercrime data collection continues and evolves, ideally building from the conceptual base suggested in our recommended taxonomy, it will be important to address the “cyber” part of cybercrime as well as the “crime” component. Metrics in the cybersecurity realm, such as the nature and volume of detected-but-deflected attempts to bring down network resources or analyses of specific technological vectors along which cyberattacks are conducted, may better inform future cybercrime metrics, just as studies of policing, community resilience, and deterrence enhance understanding of crime.