Cybercrime Classification and Measurement (2025)

Chapter: 3 Approaches to Cybercrime Classification

3

Approaches to Cybercrime Classification

For purposes of our study of cybercrime classification and measurement, Chapter 2’s review of the handling of cybercrime definitions in current crime statistics and current cybercrime/cybersecurity measures affirms that there is no universally agreed-upon definition of cybercrime and its types. To the extent that current data collections follow a taxonomy of cybercrime, it is a taxonomy only in the sense of being a list, otherwise lacking organizational principles in its construction. This is not to disparage the existing collections; there are admirable aspects to the effectively data-defined nature of the Internet Crime Complaint Center’s code list, for example, where entries shuffle on or off the list—or are split or combined as appropriate—based on their observed frequency.

Our fundamental task was to review current data collections and organizational schema to suggest a better approach, which is described in this chapter. We first identify previous attempts to define a rigorous taxonomy for cybercrime in its own right as well as to nest cybercrime in the context of crime writ large. Based on this review and our observations of the current data-collection systems, we define a set of desired principles for our classification and then outline our suggested taxonomy.

CYBER-SPECIFIC TAXONOMIES: CYBERCRIME IN ISOLATION

Our review of the partitioning and classification of cybercrime in standalone taxonomies owes greatly to the comprehensive literature review of Phillips et al. (2022) as well as their proposed classification schema, which was subsequently summarized along with other schema in the Brinton et al.

(2023) “environmental scan” of cybercrime measurement to inform options for cybercrime content in the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS).

Arguably the most common dimension along which cybercrime offenses are divided in proposed taxonomies—including the language of our panel’s statement of task—is the degree of cyber or computer involvement. Phillips et al. (2022) attribute a basic two-way split between cyber-enabled and cyber-dependent crime to an original definition advanced by Brenner (2007) and a three-way split that adds cyber-assisted crime to Wall (2005). In the Phillips et al. (2022, p. 385) rendition of the Wall (2005) taxonomy, the basic categories are as follows:

- Cyber-dependent crime/pure cybercrime, in which cyber/computer involvement is absolutely essential to the offense, which could not have occurred without it; this includes hacking, ransomware, and malware deployment.

- Cyber-enabled crime/hybrid cybercrime, in which cyber/computer involvement facilitates the offense or makes it easier to perpetrate, but the offense could ultimately have been accomplished by other means; this includes fraud and the dissemination of child sexual abuse material.

- Cyber-assisted crime/computer-assisted traditional crime, in which the cyber involvement is incidental to a real/physical–world crime; this includes criminal communications or the use of information and communication technology (ICT) to lure a victim into a physical attack.

Phillips et al. (2022, p. 384) attribute to Wall (2007) a related dimension along which cybercrime might be split—namely, the role of “the machine” in the offense:

- Crimes against the machine, or computer integrity crimes (akin to cyber-dependent crime);

- Crimes using the machine, combining various computer-assisted or computer-enabled crimes such as fraud; and

- Crimes in the machine, or computer content/content-related crimes, in which the cyber/computer involvement is the necessary communication conduit (e.g., for online dissemination of child sexual abuse material or online hate incitement).

Statistics Canada rolls cybercrimes into a similar two-level split between ICT being either the target of the offense or the instrument of the offense (Sauvé & Silver, 2024).

Brenner (2004) suggests a breakdown of cybercrimes by the extent of harm—individual harm, systemic harm, and inchoate harm—that evokes the very loose categorization of offenses in the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS; discussed later in this chapter) as crimes against individuals, society, or property. Gordon and Ford (2006, p. 13) propose a distinction between Type I and Type II cybercrime; the former is “mostly technological” in nature while the latter “has a more pronounced human element.” More commonly, though, proposed cybercrime taxonomies work to distill some set of fundamental nature-of-harm groupings:

- One of the earliest proposed cybercrime taxonomies (Wall, 2001) designated Cyber-Trespass, Cyber-Deception/Theft, Cyber-Pornography and Obscenity, and Cyber-Violence as its fundamental offenses.

- Marcum and Higgins (2019) denote five basic categories: Cyberbullying and Cyberstalking, Digital Piracy, Hacking and Malware, Identity Theft, and Sex-Related Crimes Online (further subdividing cyberbullying into five types and hacking/malware into six types).

- The CCC (Wright & Parker, 2023) described in Chapter 2, which is the basis for new cybercrime data collection in Canadian police-report statistics, identifies nine top-level categories as basic offenses—Malware; System and Service Availability; Information Gathering; Intrusion; Data Release (information security compromise); Frauds; Abusive Content; Exploitation, Harassment, or Abuse of a Person; and Uncategorized (Wright, 2024; Wright & Parker, 2023).

Finally, in the context of cybercrime-specific taxonomies, it is instructive to examine how cybercrime types are defined in international law, namely by the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime of 2001 (Council of Europe, 2001) and by the draft United Nations (UN) Convention on Cybercrime (United Nations, 2024), which cleared critical committee votes in August 2024 and was adopted by the General Assembly on December 24, 2024.1 High-level categories of both treaty instruments are depicted in Box 3-1. Core nature-of-harm categories—illegal access, interception, and interference—are shared between the two treaty documents, with the 2024 UN convention adopting more modern nomenclature (e.g., ICT rather than computer systems) and taking a particularly strong stance against child sexual abuse material, as well as adding the distinctly cyber-enabled offense of laundering proceeds of crime.

___________________

1 See https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/cybercrime/convention/home.html

BOX 3-1

Basic Cybercrime Types Identified in the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime (2001) and the Draft United Nations Convention on Cybercrime (August 2024)

Budapest Convention on Cybercrime

- Offences against the confidentiality, integrity and availability of computer data and systems

- Illegal access

- Illegal interception

- Data interference

- Misuse of devices

- Computer-related offences

- Computer-related forgery

- Computer-related fraud

- Content-related offences

- Offences related to child pornography

- Offences related to infringements of copyright and related rights

Also includes articles on attempt/aiding/abetting, corporate liability, and sanctions and measures

Cybercrime (Draft August 2024)

- Illegal access [of an information and communications technology (ICT) system]

- Illegal interception [of electronic data]

- Interference with electronic data

CYBERCRIME IN CONTEXT OF ALL-CRIME TAXONOMIES

Chapter 2 and Appendix C provide considerable detail on how cybercrime content was incorporated into the NIBRS over time. Though the NIBRS offense code list (Table 2-1) does not have the rigorous structure of a fully developed classification scheme, the NIBRS is still the essential reference point for this study, so it is useful to recap highlights of the NIBRS’s handling of cybercrime matters. From the outset, NIBRS contributors were guided to code computer-related crimes as the closest underlying base crime in the NIBRS set (e.g., Fraud or Extortion), with Data Element 8 (Offender Suspected of Using [Computer Equipment]) available to mark the added context. When a concerted effort was made to increase cybercrime content, the Federal Bureau of Investigation added one purely computer-centric offense type (Hacking/Computer Invasion)

- Interference with an ICT system

- Misuse of devices

- ICT system-related forgery

- ICT system-related theft or fraud

- Offences related to online child sexual abuse or child sexual exploitation material

- Solicitation or grooming for the purpose of committing a sexual offence against a child

- Non-consensual dissemination of intimate images

- Laundering of proceeds of crime

Also includes articles on liability of legal persons; participation and attempt; statute of limitations; and prosecution, adjudication, and sanctions

NOTES: Each subcategory is typically accompanied by one or more reservations or declarations that signatory nations may choose to exercise in the ratification process, identifying sections that they decline to add to national law or handle differently. Two additional protocols were added to the Budapest Convention in 2003 and 2022, the 2003 protocol being relevant here as it defined additional offenses for “acts of a racist and xenophobic nature committed through computer systems” (European Treaty Series No. 189). However, the United States was not a signatory to the 2003 protocol and thus has not ratified (it was a signatory to the 2022 protocol on cooperative disclosure of electronic evidence, but has not been ratified). The United Nations Convention on Cybercrime was adopted by the General Assembly on December 24, 2024, and is expected to be opened for member nation ratification in 2025.

SOURCE: Panel generated from Council of Europe (2001) and United Nations (2024).

and one heavily computer-based offense (Identity Theft) to its roster, both with code numbers that positioned them as variants in the broader category of fraud. Cyberspace was also added as a response option to NIBRS Data Element 9, the location of the incident, providing another hook to indicate potential cybercrime involvement.

In the early 2010s, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2015; UNODC) convened an expert group to construct an International Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes (ICCS), with the intent of truly covering all crime, touching on areas such as environmental crime that were completely new to traditional crime statistics. The UNODC working group chose to address cybercrime by defining a limited number of what we have just described as cyber-dependent crimes, under the general heading of acts against public safety and state security:

| 09 | Acts against public safety and state security |

| 0903 | Acts against computer systems |

| 09031 | Unlawful access to a computer system |

| 09032 | Unlawful interference with a computer system or computer data |

| 090321 | Unlawful interference with a computer system |

| 090322 | Unlawful interference with computer data |

| 09033 | Unlawful interception or access of computer data |

| 09039 | Other acts against computer systems |

A critical part of the ICCS design is a system of tags, also termed attributes or disaggregating variables, to provide additional detail or context about the offense. Among the ICCS’s disaggregation variables, “Cy” or Cybercrime-related “serves to identify various forms of crime committed with the use of a computer, internet fraud, cyber-stalking or violation of copyright through electronic dissemination” (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2015, p. 21). The “Cy” tag became the primary mechanism for coding cyber-enabled crime.

Tasked with developing a taxonomy for all types of crime in the American context, our predecessor Panel on Modernizing the Nation’s Crime Statistics (hereafter, MNCS panel; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [National Academies], 2016a, pp. 129–130, 136) maintained the same set of core cyber-dependent crimes—the fundamental offenses of unlawful access, unlawful interference, and unlawful interception—as the ICCS. However, the MNCS panel changed the numbering scheme (e.g., 09 to 5, 0903 to 5.3, and so forth) and shifted the group to the top-level “Acts against property only” category. The MNCS panel also sought to clarify the meaning of the “Cybercrime-related” tag, making it a Yes/No variable “depending on whether the use of computer data or computer systems was an integral part of the modus operandi of the offense.” Because of its inclusion in the NIBRS, the MNCS panel also added Identity Theft to its offense tables as number 7.1.2, a disaggregate version of 7 (Acts involving fraud, deception, or corruption) and 7.1 (Fraud). In this way, both the MNCS panel and the ICCS adhere to a definition-plus-attribute structure to allow for the coding of detailed events without explicitly building out dozens of detailed codes and definitions.

Principles and Desired Characteristics of a Taxonomy

As the MNCS panel did in developing its all-crime classification (National Academies, 2016a, pp. 117–124), we settled on a set of principles and desired characteristics in developing our own recommended taxonomy. The current panel’s opinion is as follows:

- The taxonomy of cybercrime should satisfy all the requirements of a classification for statistical purposes; namely, it should be exhaustive of the entire space of cybercrime, should partition that space into mutually exclusive categories, and should follow a hierarchical structure to the extent practicable.

- Definitions of cybercrime offenses should be behavioral in nature and focus on the underlying action. As much as possible, the basic definitions should avoid the use of technical jargon and references to specific technologies or computing techniques. In the parlance of the Vocabulary for Event Recording and Incident Sharing (VERIS) described in Chapter 2, the taxonomy’s categories should keep Actions distinct from specific reference to the Assets, Actors, and vectors of the attack.2

- Relatedly, the number of major categories should be kept as small as possible, and the corresponding offenses should be relatively coarse in construction. This aims to avoid technology-specific jargon and to make the taxonomy easier to interpret and implement. However, this structure also addresses our panel’s charge and its principal focus on incorporating the taxonomy into NIBRS and direct reporting from law enforcement agencies—fewer, coarser categories are better suited to data collection in contexts when technical details may not be known or may be impossible to accurately parse and capture in conventional police records management systems.

- As much as possible, definitions in the proposed taxonomy should (a) be consistent with but not strictly limited by the text of state and federal penal codes (because, by definition, crime must be unlawful behavior);and (b) be consistent with existing definitions in major relevant data collections.

- The taxonomy should include both practical, feasible, and (relatively) easily implementable categories, as well as categories that are broader and more aspirational in nature.

- The taxonomy should not be conceived or portrayed as a static, unchanging document; it should be amenable to—and will vitally depend upon—a regular program of monitoring and revision based on findings from resulting data collection.

___________________

2 The fourth A in the VERIS framework, Attributes (i.e., the security attributes of the asset affected in the incident), is more difficult to keep distinct from category definitions, as they speak to broader motives for the offending action. See http://verisframework.org/incident-desc.html for further detail on VERIS.

Phillips et al. (2022) combined several dimensions of cybercrime-specific taxonomies in developing their own proposed classification. Their classification framework (Phillips et al., 2022, Figure 1) delineates six main substantive categories—attacks against data and systems, attacks against property or theft, interpersonal violence, sexual violence, violence against groups, and incidental technology use—as well as a more vague violence (general) category and two overarching cross-category bundles of terms. Combining several elements as it does, the Phillips et al. (2022) taxonomy was persuasive as we shaped our own classification. But, for our purposes, it has three key liabilities. First—and understandably, given its genesis in studies of child psychology—it pointedly extends beyond cybercrime and into cyberdeviance, bad behavior that is not necessarily unlawful/criminal. Second, though it effectively pulls many concepts together into one diagram, it stops short of actual definitions for any of its terms. Third, the overarching “violence (general)” and “cross-category” categories are inherently technical violations of the mutual exclusivity criterion we seek for a classification for statistical purposes. That said, the literature review and the proposed classification framework suggested by Phillips et al. (2022) were both valuable contributions to our work.

RECOMMENDED CLASSIFICATION OF CYBERCRIME

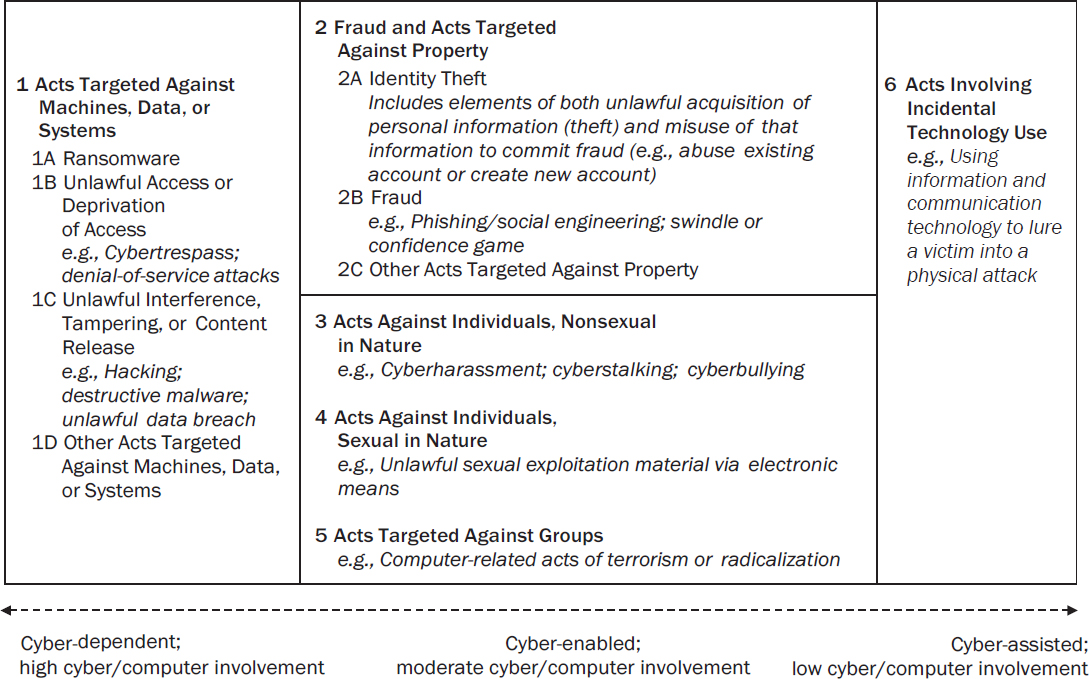

The taxonomy we recommend for cybercrime classification and measurement is provided in short form in Recommendation 3-1, expressed graphically in Figure 3-1, and fully articulated with detailed definitions and inclusions in Appendix B.

Recommendation 3-1: The following concise taxonomy should be used as an initial framework for developing statistical measures of cybercrime in the United States:

-

Acts Targeted Against Machines, Data, or Systems

1A Ransomware

1B Unlawful Access or Deprivation of Access

1C Unlawful Interference, Tampering, or Content Release

1D Other Acts Targeted Against Machines, Data, or Systems

-

Fraud and Acts Targeted Against Property

2A Identity Theft

2B Fraud

2C Other Acts Targeted Against Property

- Acts Against Individuals, Nonsexual in Nature

- Acts Against Individuals, Sexual in Nature

- Acts Targeted Against Groups

- Acts Involving Incidental Technology Use

NA Acts with No Cyber/Computer Involvement

SOURCE: Panel generated.

This recommended taxonomy is designed to be exhaustive of the degree of cyber/computer involvement, with main category 1 being pure cyber-dependent crime, categories 2–5 representing more moderate levels of cyberenabling of base crimes, and category 6 representing only incidental cyber/computer involvement (with the final category of Acts with No Cyber/Computer Involvement completing the partitioning). Categories 2–5 are structured by the target of the offense, whether property, individuals, or groups of people. Within major categories 1 and 2, we sparingly delineate specific offenses, preserving Ransomware and Identity Theft as main offenses because of their prominence in public discussion. Category 1B hearkens to the original Wall (2001) designation of “Cyber-Trespass,” or simple access, as a fundamental nature of harm in cybercrime, while group 1C pivots to actual damage to computers, networks, or data.

The final shape of this recommended taxonomy resulted from our intention for the classification to be actionable and implementable with or without a massive revision of the classification for all crime. We concur with the MNCS panel that the nation’s current crime statistics fall short of capturing information on new, important, and emerging types of crime, and we support the aspirational goal of a next-generation NIBRS that can cover a wider array of offense types. But—in the present—we also recognize the uniquely delicate and challenging climate for crime and cybercrime data collection. Accordingly, our suggestion is to use the recommended taxonomy as an enhanced attribute flag for incidents—one that can be applied regardless of the underlying set of base crimes. We concur with the MNCS panel that much information could be gained by recording events as base offenses plus an attribute flag (in this case, for cyber/computer involvement).

Recommendation 3-2: Rather than have a cybercrime classification function as parallel or adjunct to existing crime classifications, the taxonomy presented in Recommendation 3-1 should be implemented in crime data–collection systems as an attribute, flag, or modifier to code incidents in conjunction with the system’s base classification of criminal offenses.

Our Appendix B definitions—developed to apply independently of the base offense list—do not necessarily square completely with the definitions in the current NIBRS or any other particular system. For instance, we define cyberharassment and cyberstalking as examples of offenses that may be included in our category 3, Acts Against Individuals, Nonsexual in Nature. This is consistent with the MNCS panel’s formulation, which defines both Harassment and Stalking as course-of-conduct offenses, requiring a demonstrated pattern of activity over a period of time, but it does not comport with the current NIBRS, in which Stalking is listed as an included offense

under Intimidation, which is not a course-of-conduct offense, and Harassment is not separately defined at all.

That said, implementing this cybercrime-classification flag in the current NIBRS could fit very well with the current Hacking/Computer Invasion and Identity Theft offenses. The category 1 subdivisions of the taxonomy would provide meaningful disaggregation of the base offense of Hacking/Computer Invasion (pure cyber-dependent crime), while categories 2–5 would shed light on the target of the cybercrime-related instances of other NIBRS base offenses. Meanwhile, Identity Theft is a particularly challenging offense to operationalize because the name implies limitation to theft (i.e., unlawful acquisition of personally identifiable information), but it is traditionally interpreted to include elements of identity fraud (e.g., subsequent use of that personal information to open a new credit card). This two-pronged definition is used by the NCVS Identity Theft Supplement, by NIBRS itself,3 and by researchers such as Golladay (2020), and we adopt this broader definition in Appendix B, as well. In practice, this means that the ideal way to enter such an offense in NIBRS would be to make use of the system’s capacity for associating multiple offenses with the same incident—that is, to include a record with (at least) offenses of Identity Theft and Credit Card Fraud, while selecting the 2A Identity Theft option in our cybercrime-involvement variable.

___________________

3 Identity Theft is defined in NIBRS as “wrongfully obtaining and/or using another person’s personal data” (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2023b, p. 27).

This page intentionally left blank.