Cybercrime Classification and Measurement (2025)

Chapter: 2 Treatment of Cybercrime in Current Data Collections

2

Treatment of Cybercrime in Current Data Collections

In this chapter, we briefly review how cybercrime and related concepts are measured in existing and developing data systems, with particular eye to the categorization schemes used in those systems.

CYBERCRIME HANDLING IN THE NATIONAL INCIDENT-BASED REPORTING SYSTEM

The Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program is a data series compiled and maintained by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) based on the voluntary data contributions of thousands of state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) law enforcement agencies.1 The program began in 1929

___________________

1 Because it is directly quoted in the Better Cybercrime Metrics Act (see Appendix A) and because it is germane to the panel’s task, an important exception to the UCR Program’s voluntary reporting structure deserves notice. The Uniform Federal Crime Reporting Act of 1988 (P.L. 115-393; 102 Stat. 4468; 34 U.S.C. § 41303) requires “all departments and agencies within the Federal government (including the Department of Defense) which routinely investigate complaints of criminal activity” to report crimes in their jurisdictions as part of the UCR Program, “limited to the reporting of those crimes comprising the Uniform Crime Reports.” However, it would be 27 years (and a concerted effort to get some federal law enforcement agencies, including the FBI itself, to report) before UCR results for federal agencies were reported in the UCR Program’s Crime in the United States report. Even the 2023 “Federal Tables” of Crime in the United States (accessible from the FBI’s Crime Data Explorer at https://cde.ucr.cjis.gov/LATEST/webapp/#/pages/downloads) include submissions from 41 federal agencies (most being Offices of Inspector General, and not including the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which is tabulated separately) and are limited to the major violent and property crimes of the old Summary Reporting System described in this paragraph and in Box 2-1.

BOX 2-1

Crime Classification in the Uniform Crime Reporting Summary Reporting System, 2014

Part I Classes

- Criminal homicide

1a Murder and nonnegligent manslaughter

1b Manslaughter by negligence

- Rape

2a Rape

2b Attempts to commit rape

2c Historical rape

- Robbery

3a Firearm

3b Knife or cutting instrument

3c Other dangerous weapon

3d Strong-arm—hands, fists, feet, etc.

- Aggravated assault

4a Firearm

4b Knife or cutting instrument

4c Other dangerous weapon

4d Strong-arm—hands, fists, feet, etc.—aggravated injury

- Burglary

5a Forcible entry

5b Unlawful entry—no force

5c Attempted forcible entry

- Larceny—theft (except motor vehicle theft)

6Xa Pocket-picking

6Xb Purse-snatching

6Xc Shoplifting

6Xd Thefts from motor vehicles

6Xe Theft of motor vehicle parts and accessories

6Xf Theft of bicycles

6Xg Theft from buildings

6Xh Theft from coin-operated device or machine

6Xi All other

- Motor vehicle theft

7a Autos

7b Trucks and buses

7c Other vehicles

- Arson

- Structural (Codes 8a–g cover different types of structures)

- Mobile (Codes 8h–i differentiate between motor vehicles and other mobile property)

- Other (Code 8j)

A Human trafficking—commercial sex acts

B Human trafficking—involuntary servitude

Part II Classes

- Other assaults—simple, not aggravated (also codes 4e “as a quality control matter and for the purpose of looking at total assault violence”)

- Forgery and counterfeiting

- Fraud

- Embezzlement

- Stolen property: buying, receiving, possessing

- Vandalism

- Weapons; carrying, possessing, etc.

- Prostitution and commercialized vice

16a Prostitution

16b Assisting or promoting prostitution (also coded 30)

16c Purchasing prostitution (also coded 31)

- Sex offenses (except rape and prostitution and commercialized vice)

- Drug abuse violations

- Gambling

- Offenses against the family and children

- Driving under the influence

- Liquor laws

- Drunkenness

- Disorderly conduct

- Vagrancy

- All other offenses

- Suspicion

- Curfew and loitering laws (persons under 18)

- Runaways (persons under 18)

SOURCE: Reprinted from National Academies (2016a, Box 2.1), in turn excerpted from Federal Bureau of Investigation (2013b).

after the completion of a standard manual for UCR data collection by the International Association of Chiefs of Police. For decades, the centerpiece of the UCR Program was the Summary Reporting System (SRS), which—as the name implies—required the compilation of summary counts of offenses known (reported) to law enforcement agencies as well as arrest totals for seven major crime types dubbed Part I offenses. These seven Part I offenses (i.e., murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny-theft, and motor vehicle theft) were selected both because of their perceived severity and their supposed consistency in definition across U.S. states; in later years, arson and human trafficking were added to Part I by law. Meanwhile, only arrest counts were collected for several other offenses, dubbed Part II crimes and generally interpreted as less severe offenses. “False personation, pretense, statement, document, representation, claims, evidence, etc.” and “fraudulent use of telegraph, telephone messages”—predecessors of the eventual offenses of identity theft and wire fraud—were both listed as examples of the Part II offense of “embezzlement and fraud” in the original International Association of Chiefs of Police (1929, p. 28) manual that defined the UCR Program.

Part I and Part II SRS offenses, as they stood in 2014, are listed in Box 2-1. The hallmark characteristic of the SRS was its rigid adherence to a Hierarchy Rule—hierarchy in the sense of compression of information rather than rolling up (or down) to different levels of granularity in measurement. Under the SRS Hierarchy Rule, only the most serious offense in a crime incident was to be reported—homicide being the most serious, and continuing in the order listed in Box 2-1. So, for instance, only the homicide would be counted in an incident involving both homicide and motor vehicle theft. Moreover, popular attention was drawn principally to Part I offenses in determining whether crime rates were rising and falling; the arrest-only Part II offenses were given substantially less visibility.

After a task force issued recommendations for future development of the UCR Program in 1985 (Poggio et al., 1985), work began on what would become the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), with a few pioneer law enforcement agencies beginning to submit data in the new format by the late 1980s.2 The NIBRS eliminated the SRS Hierarchy Rule; all offenses (up to 10) committed as part of a single crime incident are meant to be included in a NIBRS data record. NIBRS data records for each incident grew to include nearly 60 data elements across six segments, providing a

___________________

2 The task force on options for the future of the UCR Program was convened by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), an early moment in a continuing partnership between the BJS and the FBI. More recently, the BJS’s grantmaking authority was essential to the multiyear National Crime Statistics Exchange program that worked to boost reporting to the FBI’s UCR Program in NIBRS format prior to 2021.

wealth of information about each incident. The six segments of a NIBRS data record are as follows: Administrative (e.g., date and time of incident and identity of reporting law enforcement agency), Offense (e.g., offense type, method, and location), Property (e.g., type and value of property involved in the crime), Victim (e.g., demographic information and nature of relationship to offender), Offender, and Arrestee (if applicable).

Importantly, the NIBRS format permitted not only reporting of multiple offenses per incident but also a much wider variety of offense categories (see Table 2-1). The current NIBRS includes 71 specific Group A offenses under 28 categories, for which the full incident detail is meant to be reported; 10 Group B offenses are, like the predecessor SRS Part II, subject only to arrest-count reporting (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2023b, pp. 16, 42). As depicted in Table 2-1, Group A offenses are also loosely grouped into three overarching categories, depending on whether the offense is deemed a crime against a person, against property, or against society.

Uptake of the new, detailed NIBRS reporting required substantial time and resources, and thus proceeded at a markedly slower rate than initially projected. Though NIBRS-format data were available to and analyzed by some researchers, those data were ultimately a self-selected sample of law enforcement agencies and not statistically representative of any broader population; the UCR Program itself did not publish a report of tabulations from NIBRS data until 2013. However, after 30 years of coexistence—the SRS continuing to be the official UCR format while law enforcement agencies were encouraged to invest resources in making the technological upgrade to the NIBRS format—the FBI officially discontinued the SRS as of January 1, 2021. Not all law enforcement agencies made the transition in time; as shown in Table 2-2, about 34 percent of federal and SLTT law enforcement agencies did not submit NIBRS-format data in 2021 and 2022, notably including the nation’s two largest local law enforcement agencies, the New York Police Department and the Los Angeles Police Department (U.S. Department of Justice, 2023, p. 8). Most law enforcement agencies in five populous states—California, New York, Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Florida—did not report to NIBRS in 2021; NIBRS coverage in those states improved in 2022, though Florida and Pennsylvania remained at 7.7 and 9.1 percent agency participation, respectively.3 Accordingly, the FBI’s UCR Program continues to work on increasing full NIBRS participation.

Prior to 2021, cybercrime could only (at best) enter UCR figures if it was characterized as either a type of fraud or as “all other offenses”—both Part II entries in the SRS hierarchy, thus as an arrests-only count rather

___________________

3 See https://www.themarshallproject.org/2022/06/14/what-did-fbi-data-say-about-crime-in-2021-it-s-too-unreliable-to-tell and https://www.themarshallproject.org/2023/07/13/fbi-crime-rates-data-gap-nibrs

TABLE 2-1 National Incident-Based Reporting System Offense Codes

| NIBRS Code | Offense Name | Eligible for Location 58 Cyberspace | Crime Against |

|---|---|---|---|

| 09A | Murder and Nonnegligent Manslaughter | Person | |

| 09B | Negligent Manslaughter | Person | |

| 09C | Justifiable Homicide | Not a Crime | |

| 11A | Rape | Person | |

| 11B | Sodomya | Person | |

| 11C | Sexual Assault With An Objecta | Person | |

| 11D | Fondling | Person | |

| 13A | Aggravated Assault | Person | |

| 13B | Simple Assault | Person | |

| 13C | Intimidation | Y | Person |

| 23A | Pocket-picking | Property | |

| 23B | Purse-snatching | Property | |

| 23C | Shoplifting | Property | |

| 23D | Theft From Building | Property | |

| 23E | Theft From Coin-Operated Machine or Device | Property | |

| 23F | Theft From Motor Vehicle | Property | |

| 23G | Theft of Motor Vehicle Parts or Accessories | Property | |

| 23H | All Other Larceny | Property | |

| 26A | False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game | Y | Property |

| 26B | Credit Card/Automated Teller Machine Fraud | Y | Property |

| 26C | Impersonation | Y | Property |

| 26D | Welfare Fraud | Y | Property |

| 26E | Wire Fraud | Y | Property |

| 26F | Identity Theft | Y | Property |

| 26G | Hacking/Computer Invasion | Y | Property |

| 26H | Money Launderinga | Y | Society |

| 30A | Illegal Entry into the United Statesb | Society | |

| 30B | False Citizenshipb | Society | |

| 30C | Smuggling Aliensb | Society | |

| 30D | Re-entry after Deportationb | Society | |

| 35A | Drug/Narcotic Violations | Y | Society |

| 35B | Drug Equipment Violations | Y | Society |

| NIBRS Code | Offense Name | Eligible for Location 58 Cyberspace | Crime Against |

|---|---|---|---|

| 36A | Incest | Person | |

| 36B | Statutory Rape | Person | |

| 39A | Betting/Wagering | Y | Society |

| 39B | Operating/Promoting/Assisting Gambling | Y | Society |

| 39C | Gambling Equipment Violations | Y | Society |

| 39D | Sports Tampering | Society | |

| 40A | Prostitution | Y | Society |

| 40B | Assisting or Promoting Prostitution | Y | Society |

| 40C | Purchasing Prostitution | Y | Society |

| 49A | Harboring Escapee/Concealing from Arrestb | Society | |

| 49B | Flight to Avoid Prosecutionb | Society | |

| 49C | Flight to Avoid Deportationb | Society | |

| 58A | Import Violationsb | Society | |

| 58B | Export Violationsb | Society | |

| 61A | Federal Liquor Offensesb | Society | |

| 61B | Federal Tabacco Offensesb | Society | |

| 64A | Human Trafficking, Commercial Sex Acts | Y | Person |

| 64B | Human Trafficking, Involuntary Servitude | Y | Person |

| 100 | Kidnapping/Abduction | Person | |

| 101 | Treasonb | Y | Society |

| 103 | Espionageb | Y | Society |

| 120 | Robbery | Property | |

| 200 | Arson | Property | |

| 210 | Extortion/Blackmail | Y | Property |

| 220 | Burglary/Breaking and Entering | Property | |

| 240 | Motor Vehicle Theft | Property | |

| 250 | Counterfeiting/Forgery | Y | Property |

| 270 | Embezzlement | Y | Property |

| 280 | Stolen Property Offenses | Y | Property |

| 290 | Destruction/Damage/Vandalism of Property | Y | Property |

| 360 | Failure to Register as a Sex Offenderb | Society | |

| 390 | Pornography/Obscene Material | Y | Society |

| NIBRS Code | Offense Name | Eligible for Location 58 Cyberspace | Crime Against |

|---|---|---|---|

| 510 | Bribery | Y | Property |

| 520 | Weapon Law Violations | Y | Society |

| 521 | Violation of National Firearms Act of 1934b | Y | Society |

| 522 | Weapons of Mass Destructionb | Society | |

| 526 | Explosivesb | Y | Society |

| 620 | Wildlife Traffickingb | Society | |

| 720 | Animal Cruelty | Society | |

| 90B | Curfew/Loitering/Vagrancy Violations | ||

| 90C | Disorderly Conduct | ||

| 90D | Driving Under the Influence | ||

| 90F | Family Offenses, Nonviolent | ||

| 90G | Liquor Law Violations | ||

| 90J | Trespass of Real Property | ||

| 90K | Failure to Appearb | ||

| 90L | Federal Resource Violationsb | ||

| 90M | Perjuryb | ||

| 90Z | All Other Offenses |

a Currently recoded to 11A but slated to be rejected as valid code in 2025.

b Offenses eligible for reporting by federal and tribal law enforcement agencies only.

SOURCES: Federal Bureau of Investigation (2023b); panel added column on cyberspace location eligibility based on Federal Bureau of Investigation (2023a, p. 52).

than a measure of offenses known to police. From the outset, then, the NIBRS has markedly increased the capacity for reporting cybercrime. In Appendix C, we trace the NIBRS handling of cybercrime-related concepts through various revisions of the system’s user manual, briefly summarized in the following points.

In terms of defined crime categories, the NIBRS’s long-standing guidance was to code computer crime offenses as the closest substantive offense—for instance, as fraud or embezzlement. By 2013, the offense of Wire Fraud was redefined in the NIBRS to include the use of computers and electronic messaging to perpetrate fraud. In 2014, the FBI director approved the addition of Hacking/Computer Invasion and Identity Theft as Group A offenses in the NIBRS, specifically to improve coverage of cybercrime. Both offenses fall under the general heading of crimes against

| 2021 | 2022 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Submitted NIBRS Data | Total Agencies | Percentage of Agency Participation | Submitted NIBRS Data | Total Agencies | Percentage of Agency Participation | |

| State and Local Agencies | 12,523 | 18,746 | 66.8 | 12,515 | 18,678 | 67.0 |

| Tribal Agencies | 178 | 212 | 84.0 | 172 | 214 | 80.4 |

| Federal Agencies | 41 | 99 | 41.4 | 38 | 99 | 38.4 |

| U.S. Territories | 1 | 5 | 20.0 | 1 | 5 | 20.0 |

| All Agencies | 12,742 | 19,203 | 66.4 | 12,725 | 19,139 | 66.5 |

NOTES: The source report estimates that 73 percent of the U.S. population is represented by the 12,725 agencies that submitted National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) data in 2022. The number of agencies can decrease from year to year if the agency enters “covered” status, meaning that another agency assumes responsibility for reporting crime data for it, or it becomes dormant.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Justice (2023, pp. 7–8).

property and bear code numbers designating them as variants of fraud. Though Identity Theft does not necessarily involve the use of computers or information and communication technology (ICT), electronic means have almost certainly developed into a primary method.

Since the creation of the NIBRS, a data element in the Offender segment—currently dubbed Data Element 8, Offender Suspected of Using—has seemed to permit coding offenses as being computer-related in their conduct through the option of “Computer Equipment.” However, the variable has always been curiously defined, fusing an offender’s suspected use of alcohol or drugs—two factors that potentially speak to an offender’s alertness or impairment during the offense—with “Computer Equipment,” a factor related to the general method of attack. As Appendix C notes, though, the extent to which Data Element 8 functions (or is meant to function) as a partial flag of cybercrime is an open question, as the most recent version of the NIBRS user manual describes the response option as Offender Suspected of Using “Computer Equipment (Handheld Devices)” and the only examples of the element’s use related to fatalities involving distracted driving/driving while texting. Thus, the intent of Data Element 8 pertinent to potential cybercrime involvement is unclear.

In addition to approving the new Hacking/Computer Invasion and Identity Theft categories, the FBI director approved the addition of code 58, Cyberspace, as a potential response to Data Element 9’s query for the location of the offense. A column in Table 2-1 indicates the NIBRS offenses that the most recent version of the NIBRS Technical Specification (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2023a) indicates as eligible to use the Cyberspace code. However, since its introduction as a location response option, the user manual’s examples on the application of the Cyberspace code (detailed in Appendix C) clearly denote the internet as integral to the offense, not just computer or information technology in general (excluding, for instance, computers in isolation or in local corporate intranets).

Table 2-3 presents a basic tabulation of these two principal computer-related indicators (i.e., Offender Suspected of Using Computer Equipment and Cyberspace as Location) from the 2022 public-use NIBRS Incident File, by the first offense coded in the record. The table is meant as a rough indicator of how often the two cues are used in isolation and in combination, and not as a definitive estimate of cybercrime prevalence as measured in 2022 NIBRS data. Our general impression is that there is some possible cybercrime signal in both cues but also considerable noise. For example, Cyberspace is listed as the location for many offenses for which the NIBRS Technical Specifications say the value is ineligible (e.g., rape and both aggravated and simple assault). For some offenses—Intimidation, Hacking/Computer Invasion, Wire Fraud, False Pretenses/Swindle/

| NIBRS Code | NIBRS Offense Name | Cyberspace as Location | Data Element 8 Offender Suspected of Using Computer Equipment | Both Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 09A | Murder/Nonnegligent Manslaughter | 0 | 35 | 0 |

| 09B | Negligent Manslaughter | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 09C | Justifiable Homicide | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 11A | Rape | 32 | 319 | 11 |

| 11B | Sodomy | 20 | 106 | 1 |

| 11C | Sexual Assault with an Object | 7 | 34 | 1 |

| 11D | Fondling (Indecent Liberties/Child Molesting) | 45 | 474 | 22 |

| 13A | Aggravated Assault | 24 | 666 | 6 |

| 13B | Simple Assault | 72 | 2,005 | 25 |

| 13C | Intimidation | 16,652 | 16,020 | 3,923 |

| 23A | Pocket-picking | 20 | 165 | 7 |

| 23B | Purse-snatching | 8 | 23 | 3 |

| 23C | Shoplifting | 9 | 611 | 2 |

| 23D | Theft from Building | 372 | 1,086 | 134 |

| 23E | Theft from Coin-Operated Machine or Device | 0 | 18 | 0 |

| 23F | Theft from Motor Vehicle | 480 | 994 | 103 |

| 23G | Theft of Motor Vehicle Parts/Accessories | 6 | 150 | 3 |

| 23H | All Other Larceny | 1,599 | 10,048 | 502 |

| 26A | False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game | 29,742 | 22,210 | 7,946 |

| 26B | Credit Card/Automatic Teller Machine Fraud | 13,507 | 8,291 | 3,122 |

| 26C | Impersonation | 6,305 | 3,833 | 1,427 |

| 26D | Welfare Fraud | 416 | 176 | 59 |

| 26E | Wire Fraud | 11,530 | 8,597 | 4,952 |

| 26F | Identity Theft | 23,305 | 13,436 | 6,232 |

| 26G | Hacking/Computer Invasion | 1,714 | 1,921 | 823 |

| NIBRS Code | NIBRS Offense Name | Cyberspace as Location | Data Element 8 Offender Suspected of Using Computer Equipment | Both Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35A | Drug/Narcotic Violations | 60 | 1,605 | 14 |

| 35B | Drug Equipment Violations | 5 | 102 | 3 |

| 36A | Incest | 3 | 18 | 3 |

| 36B | Statutory Rape | 15 | 146 | 8 |

| 39A | Betting/Wagering | 2 | 16 | 0 |

| 39B | Operating/Promoting/Assisting Gambling, Gambling Equipment | 4 | 43 | 1 |

| 39C | Violations | 0 | 28 | 0 |

| 39D | Sports Tampering | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 40A | Prostitution | 59 | 73 | 15 |

| 40B | Assisting or Promoting Prostitution | 39 | 131 | 18 |

| 40C | Purchasing Prostitution | 16 | 105 | 5 |

| 64A | Human Trafficking—Commercial Sex Acts | 62 | 126 | 24 |

| 64B | Human Trafficking—Involuntary Servitude | 5 | 14 | 4 |

| 100 | Kidnapping/Abduction | 20 | 133 | 10 |

| 120 | Robbery | 21 | 277 | 4 |

| 200 | Arson | 0 | 19 | 0 |

| 210 | Extortion/Blackmail | 5,140 | 4,769 | 2,062 |

| 220 | Burglary/Breaking and Entering | 104 | 780 | 25 |

| 240 | Motor Vehicle Theft | 40 | 530 | 11 |

| 250 | Counterfeiting/Forgery | 2,646 | 3,917 | 726 |

| 270 | Embezzlement | 284 | 644 | 52 |

| 280 | Stolen Property Offenses | 49 | 212 | 7 |

| 290 | Destruction/Damage/Vandalism of Property | 37 | 772 | 9 |

| 370 | Pornography/Obscene Material | 6,922 | 9,567 | 2,556 |

| 510 | Bribery | 23 | 21 | 5 |

| 520 | Weapon Law Violations | 18 | 203 | 3 |

| 720 | Animal Cruelty | 0 | 11 | 0 |

| Overall Total | 121,439 | 115,484 | 34,869 |

NOTES: National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) offenses listed in this table are the first offenses listed in the incident file. This simplification is used because the records in which either of the computer-use variables are applied tend to involve only one offense in the incident (92% of records with Cyberspace as Location, 89% of records in which offender is suspected of using computer equipment, and 89% with both). A total of 11,207,634 NIBRS incidents exist on the file. Federal agencies are not included in the data file, and hence the table omits entries for offenses eligible for reporting by federal and tribal law enforcement agencies only: 26H Money Laundering, 30A Illegal Entry into the United States, 30B False Citizenship, 30C Smuggling Illegal Aliens, 30D Re-entry after Deportation, 49A Fugitive (Harboring Escapee/Concealing from Arrest), 49B Flight to Avoid Prosecution, 49C Flight to Avoid Deportation, 58A Import Violations, 58B Export Violations, 61A Federal Liquor Offenses, 61B Federal Tobacco Offenses, 101 Treason, 103 Espionage, 360 Failure to Register as Sex Offender, 521 Violation of National Firearms Act of 1934, 522 Weapons of Mass Destruction, 526 Explosives Violations, and 620 Wildlife Trafficking.

SOURCE: Tabulation by panel member Lynn Addington from 2022 NIBRS Incident File (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2023).

Confidence Game, Extortion/Blackmail, and Pornography/Obscene Material—the two variables could seemingly be interpreted as duplicative: very roughly equal shares applying each of the two data element indicators and a sizable number of those cases applying both. However, other crimes split differently. The interpersonal “street crimes” for which one of the computer indicators is selected (e.g., Rape, Assault, Theft from Building or Motor Vehicle, All Other Larceny, and Drug/Narcotic Violations) use the Data Element 8 Offender Suspected of Using Computer Equipment option more frequently, while the balance swings toward Cyberspace as Location for offenses like Credit Card/Automatic Teller Machine Fraud, Impersonation, and Identity Theft. We return to this point in Chapter 4, suggesting the need for reexamination and assessment of the definition and intended role of both the Cyberspace as Location and Offender Suspected of Using Computer Equipment cues.

CYBERCRIME HANDLING IN THE NATIONAL CRIME VICTIMIZATION SURVEY AND ITS SUPPLEMENTS

The core National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), operated by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) with the U.S. Census Bureau as data-collection agent, is a panel household survey that employs a multistage sampling design to collect data on criminal victimization incidents, regardless of whether they were reported to local law enforcement agencies. The first-stage sample of primary sampling units—counties, groups of counties, or metropolitan areas—is performed every 10 years, several years after the

most recent decennial census. The second-stage sample of housing unit addresses (housing units) is drawn each year, with selected addresses remaining in-sample for three years (and, hence, for up to seven interviews on six-month intervals).4 The NCVS uses computer-assisted personal interviews for initial interviews and a mix of computer-assisted personal interviews and computer-assisted telephone interviews for subsequent interviews.

NCVS interviews begin with the interviewer asking questions of a primary respondent (dubbed the household respondent) to build a roster of household members to determine their eligibility for interview, using the NCVS-500 Control Card instrument. The NCVS seeks interviews with each member of the household age 12 or older, only permitting proxy interviews in very limited circumstances. In these interviews with household members, the NCVS-1 Basic Screen Questionnaire asks respondents to recall potential victimizations over the six-month period prior to the interview; if the victimization is one of the offense types measured by the NCVS, then the interview continues with a detailed NCVS-2 Crime Incident Report questionnaire on each incident. The questions are asked with considerable care by trained interviewers, with the aim of eliciting an accurate and complete accounting of victimizations without unduly burdening or revictimizing the respondent. To the extent possible, interviews are also performed without requiring respondents to label the crime themselves (e.g., not directly asking if the respondent was the victim of an aggravated assault), instead eliciting enough information to allow construction of the proper offense type in subsequent data processing.

The great strength of the NCVS approach is that it gathers information about crime victimizations whether or not the incidents were reported to SLTT law enforcement agencies. Thus, the NCVS serves as a complement to police-report statistics like those of UCR/NIBRS. UCR and NCVS estimates are complementary, nonredundant measures, and comparison between the sources and their trends provides a more comprehensive view of crime in the United States. However, the resulting insight into the “dark figure of crime” not reported to police (Biderman & Reiss, 1967) depends upon the aptness of the comparison between the UCR and the NCVS, namely the consistency of definitions and concepts between the two sources. The NCVS began (as the National Crime Surveys) in the 1970s, and so its essential point of comparison was—and largely remains—the Part I offenses of the UCR SRS. Accordingly, the underlying crime classification used in

___________________

4 The NCVS also includes a sample of group quarters (GQ) locations that is drawn from the first-stage primary sampling units every three years. Only certain types of noninstitutional GQs are eligible for inclusion, including college housing, group homes, and workers’ quarters and dormitories; institutional GQs such as correctional facilities and skilled nursing facilities, as well as other noninstitutional GQs like military quarters, shelters, and maritime vessels, are out-of-scope for the NCVS (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2017).

NCVS processing, shown in Box 2-2, is consistent with the “street-crime” focus of SRS crime categorization in Box 2-1, with the addition of Purse Snatching/Pocket Picking and—the NCVS being premised on self-reported victimization incidents—the exclusion of homicide. There are important practical reasons for keeping the core NCVS focused on a relatively small set of crimes, including time burden and facilitating cooperation with survey respondents. Asking additional questions on the NCVS-1 Basic Screen Questionnaire lengthens the time of the interviews, particularly if those questions elicit additional victimization instances that would be subject to the same detailed NCVS-2 Crime Incident Report questionnaire.

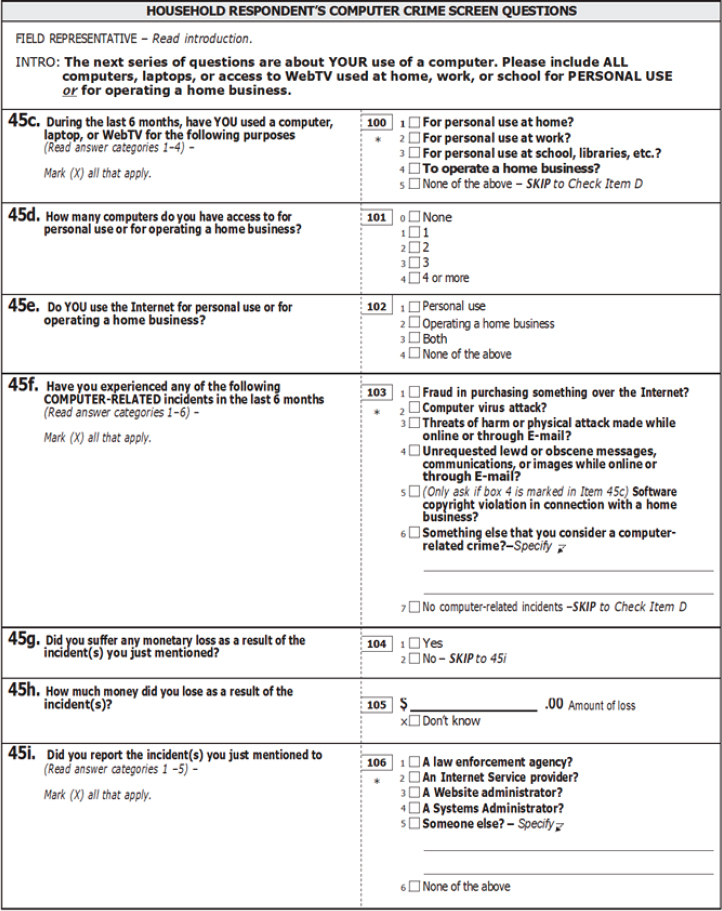

The NCVS has a long-standing penchant for improvement and reinvention; a major redesign in the early 1990s occasioned the formal name change from the National Crime Survey to the current NCVS, with a simultaneous retooling of the Basic-Screen-Questionnaire-and-Incident-Report approach. The 2024 NCVS will contain new instruments following another multiyear redesign, again aiming to increase the amount of contextual information captured in the interview while making the experience as easy as possible for respondents. So, in the context of cybercrime measurement, it is important to recognize that the NCVS did critical early work in this area. Figure 2-1 displays the bank of computer crime questionnaires that was included in the NCVS-1 Basic Screen Questionnaire between 2001 and 2004, emphasizing individuals’ experiences with computer-related crimes in the context of personal use, not work-related use (unless in operation of a home business). The question set prompted respondents to recall five types of computer-related crime—fraud in an online purchase, computer virus, threats by online messaging or email, unrequested obscene communications via online means, and software copyright violation, as well as a write-in category for other computer-related crimes. However, the computer crime questions did not request a count of such incidents, overall or by type, and reports of these computer-related incidents did not trigger completion of an NCVS-2 Crime Incident Report. The questions were added in July 2001 and removed in July 2004 (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2017, p. 53), and analyses of the resulting data do not appear to have factored into the BJS’s Criminal Victimization report series during the period.

The primary means by which the NCVS program has expanded its substantive reach—and ventured into the measurement of cybercrime concepts—is the periodic fielding of supplemental modules of questions. These supplements may be administered to NCVS respondents if they meet eligibility criteria, even if they have no crime incidents to report in the core NCVS survey. As summarized in Table 2-4, three supplements have comprised the main source of cybercrime-related content for the NCVS following the 2004 discontinuation of the computer crime questions; a fourth supplement, the School Crime Supplement (SCS), touches on the particular

BOX 2-2

Crime Classification in the National Crime Victimization Survey, 2017

Personal Crimes

Crimes of Violence

Completed

Attempted

Serious violent crimes

Rape/sexual assault

Rape

Completed

Attempted

Sexual assault

Robbery

Completed

With injury

Without injury

Attempted

With injury

Without injury

Assault

Aggravated

Completed with injury

Attempted/threatened with weapon

Simple

Completed with injury

Attempted/threatened without weapon

Purse snatching/pocket picking

Completed purse snatching

Attempted purse snatching

Pocket picking

incidence of bullying (which is typically not considered a crime in itself) and cyberbullying (which is more commonly defined as a crime).

We briefly describe these major cybercrime-related supplements in the following subsections, and one cross-cutting theme is worth noting first. The 2001–2004 NCVS-1 Basic Screen Questionnaire items on computer crime (Figure 2-1) include one that hints at a unique strength of the survey approach to measuring crime and cybercrime: in addition to providing insight on incidents that were not reported to law enforcement or other authorities, it can also suggest reasons why the incidents were not reported. This feature has also been utilized in subsequent cybercrime-related supplements. Box 2-3 presents a composite listing of response options for the

Property Crimes

Burglary

Completed

Forcible entry

Unlawful entry without force

Attempted forcible entry

Motor vehicle theft

Completed

Attempted

Theft

Completed

Less than $50

$50–$249

$250 or more

Amount not available

Attempted

NOTES: Serious violent crimes include Rape/sexual assault, Robbery, and Aggravated assault. Relative to the original source, level of indent has been changed for Crimes of violence/Completed and Attempted and for Theft/Completed/Amount not available as the original source apparently contained formatting errors. No subdivision of Serious violent crimes (i.e., Completed or Attempted) appears in the source, so none is added here.

SOURCE: Bureau of Justice Statistics (2017, Table 1).

question on why an offense was not reported to local law enforcement or other authorities from the two most recent iterations of the Identity Theft Supplement (ITS) and Supplemental Fraud Survey (SFS), to illustrate the valuable contextual information that can be derived from survey work.

Identity Theft, Fraud, and the Identity Theft Supplement and Supplemental Fraud Survey

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) began collecting consumer complaints in its Consumer Sentinel Network in 1997, and shortly thereafter received statutory authority to serve as the centralized complaint and

NOTES: Excerpt shows the questions administered to the primary respondent, known as the household respondent. The same questions were asked of each individual respondent in the household. No count of computer crime incidents was elicited in this set of questions; consequently, the follow-up NCVS-2 Crime Incident Report was not completed for any computer crime incident.

SOURCE: Excerpt from page 16 of Form NCVS-1 (5-10-2001), the National Crime Victimization Survey NCVS-1 Basic Screen Questionnaire (OMB No. 1121-0111, approval expiring 10/31/2003); https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/ncvs1.pdf

TABLE 2-4 Overview of Cybercrime-Related Supplements to the National Crime Victimization Survey

| Supplement Name | Dates Conducted | Universe of Interest | Topic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity Theft Supplement (ITS) | 2021, 2018, 2016, 2014, 2012, 2008 | NCVS respondents age 16 and older; some questions reference all such identity theft experienced in past 12 months, but detailed questions limited to single most recent incident; closing question asks whether respondent has ever been notified that their information has been part of a data breach | Identity theft/misuse of personal information of three basic varieties: misuse of an existing account (i.e., credit card/bank/email or social media/other), opening a new account, or other fraudulent purposes; respondents are asked how they think the personal information was obtained, which includes cyber/computer-related options |

| Supplemental Fraud Survey (SFS) | 2017 | NCVS respondents age 18 and older; fraud must have been completed (money must have been lost) to count; some questions reference all such fraud experienced in past 12 months, but detailed questions limited to single most recent incident | Seven types of personal financial fraud (i.e., prize or grant fraud, phantom debt collection fraud, charity fraud, employment fraud, consumer investment fraud, consumer products or services fraud, and relationship/trust fraud); cyber/computer involvement in conduct of the fraud not asked explicitly but implied more strongly for some types (e.g., most categories describing how the relationship/trust fraud was conducted are online/social media or electronic communication in nature; question as to whether charity fraud payments were made through a crowdfunding website) |

| Supplemental Victimization Survey (SVS) | 2019, 2016, 2006 | NCVS respondents age 18 and older (2006) and age 16 and older (2016 and subsequent) | Stalking, harassment, and other unwanted contact/behavior; questions ask about contacts/behaviors via social media, internet, phone, or other technology, and thus encompass cyberstalking and cyberharassment |

NOTE: NCVS, National Crime Victimization Survey.

SOURCE: Adapted and updated from Bureau of Justice Statistics (2017) through reference to individual supplement pages and questionnaires at https://bjs.ojp.gov/data-collections/search

BOX 2-3

Response Options for Why Incident Was Not Reported to Law Enforcement, 2017 Supplemental Fraud Survey and 2021 Identity Theft Supplement

Didn’t Know (SFSa)/Didn’t Know I Could (ITSb)

- Didn’t know I could (or should) report it/wasn’t sure it was a crime (SFSa)/Didn’t know that I could report it (ITSb)

- Didn’t know how to contact them (SFSa)

- Didn’t know who to contact (SFSa)

- Didn’t think about reporting it (ITSb)

- Didn’t know what agency was responsible for identity theft crimes (ITSb)

Not Important Enough

- Didn’t lose much money or got most of money back (SFSa)

- I didn’t lose any money (ITSb)

- Not important enough to report/small loss (ITSb)

Handled It Another Way (ITS b)/Took Care of It Myself (SFS a)

- Took care of it myself

- Credit card company/other organization took care of the problem (ITSb)

Didn’t Think Police Could Help

consumer resource clearinghouse for victims of identity theft. Broadening its study of the problem, the FTC commissioned Synovate (2003) to conduct a telephone household survey in March–April 2003, asking about incidences of identity theft, victims’ experiences, and whether incidents were reported to any authorities. A National Institute of Justice–funded review of data-collection work by Newman and McNally (2005) commended the pioneering FTC work and noted the lack of a centralized criminal justice database on identity theft and fraud incidents. This review spurred additional data-collection efforts associated with the NCVS.

In 2004, the respondent-level computer crime questions were removed from the NCVS-1 Basic Screen Questionnaire and a new set of 10 identity theft questions was added. As with the computer crime questions, reported identity theft instances were not subject to the detailed NCVS-2 Crime Incident Report questionnaire; however, the identity theft questions were household level, and thus only the principal household respondent was

- Found out about the incident too late (SFSa)

- Didn’t find out about the crime until long after it happened/too late for police to help (ITSb)

- Occurred in another state or outside of the United States (ITSb)

- Couldn’t provide much information about the offender (SFSa)/Couldn’t identify the offender or provide much information that would be helpful to the police (ITSb)

Personal Reasons

- Didn’t want to have any contact with the police (SFSa)

- Didn’t want to get offender in trouble (SFSa)/The person responsible was a friend or family member, and I didn’t want to get them in trouble (ITSb)

- I was too embarrassed/ashamed (SFSa)

- Too inconvenient/didn’t want to take the time

a SFS, Supplemental Fraud Survey.

b ITS, Identity Theft Supplement.

NOTE: Responses/phrases without a tag are found in both supplements. The SFS also asks why the incident was not reported to a financial institution, the Better Business Bureau, or some other entity; the response options are the same as for this question about reporting to law enforcement except that the “Didn’t want to have any contact with the police” option is omitted.

SOURCE: Panel generated from survey questionnaires at https://bjs.ojp.gov/document/itsq21.pdf and https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/sfs_2017.pdf

asked to describe any such “episodes of identity theft discovered by you or anyone in your household during the last 6 months.”5 The questions focused on three principal variants of identity theft: (a) misuse of an existing credit card account, (b) misuse of some other type of existing account, or (c) attempt to use personal information to open a new account (credit card or other). Follow-up questions asked whether the incident occurred once or in combination with other identity theft attempts, the amount lost, whether the misuse caused subsequent hardship (e.g., being turned down for loans), and how the victim became aware of the theft. Curiously, though, the questionnaire did not ask whether the incident was reported. The questions remained on the NCVS-1 Basic Screen Questionnaire into 2008, and the BJS issued two reports from these early efforts at national-level estimates (Baum, 2006, 2007).

___________________

In 2008, the set of identity theft questions was converted into a new rotating supplement to be added to the NCVS for six-month periods (Langton & Planty, 2010). The initial 2008 ITS expanded to include 67 questions in several module groups, including modules on how and when the identity theft was discovered, how the victim responded (e.g., report to authorities and to credit bureaus and satisfaction with the response), emotional impact on the victim, known information on the offender (e.g., relationship to victim), financial impact, knowledge of attempted-but-failed instances of identity theft over the past two years, and risk avoidance (i.e., measures taken in reaction to the identity theft).6 The ITS has now been fielded six times, retaining the same basic structure. Specifically regarding cybercrime, the ITS’s reference to cyber or computer involvement in the offense is not overt. However, from the first ITS to the most recent iteration in 2021,7 the ITS questionnaire has typically ended with some cyber-related questions as context. A question on whether the respondent purchased anything via the internet in the past year has dropped off, perhaps reflecting the ubiquity of ecommerce, but ITS iterations have all generally asked respondents if they have ever been notified of their personal information being involved in a data breach.

Similar to identity theft, the BJS’s extension of the NCVS to probe consumer fraud came after valuable initial telephone survey work sponsored by the FTC, conducted in 2003, 2005, 2011, and 2017.8 For its own SFS to the NCVS, fielded in October–December 2017, the BJS set out to study seven specific types of financial fraud, representing the top-level categories of financial fraud against individuals in a taxonomy for financial fraud developed by the Stanford Financial Fraud Research Center and the FINRA Foundation (Beals et al., 2015).9 These seven types, based on the purported benefit underlying the fraud, are prize or grant, phantom debt collection, charity, employment, consumer investment, consumer products or services, and relationship/trust fraud. To count an incident as fraud, the 2017 SFS required that the fraud must have been completed and the victim must have lost money (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2017, p. 12). The SFS questionnaire is designed like an NCVS in a microcosm, with a screen questionnaire eliciting recall of incidents of each of the seven types of fraud (while also endeavoring to avoid using the word “fraud”) followed by an incident report to gather more detailed information. Specifically in terms of cybercrime, it is

___________________

6 See https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/its_08.pdf

7 See https://bjs.ojp.gov/document/itsq21.pdf

8 See https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2019/10/ftc-releases-results-2017-mass-market-consumer-fraud-survey

9 The Beals et al. (2015) taxonomy was also a basis for the specification of fraud as an offense in the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2016a, pp. 144–148) classification of crime for statistical purposes.

important to note that the method by which the fraud was perpetrated is not directly asked in the SFS questionnaire but arises indirectly for some specific fraud types: the Charity Fraud incident report asks whether a crowdfunding website was used, and most of the response options describing how first contact was made in a Relationship/Trust Fraud incident are electronic or social media–related.10

The BJS summarized the resulting data from the 2017 SFS in its own report (Morgan, 2021) and commissioned a separate review of the quality of the supplement by Langton et al. (2023), which included comparison with estimates of fraud from numerous other sources, including the NIBRS and the predecessor surveys. The 2017 SFS remains the only administration of the supplement as of late 2024, likely owing to the principal, unusual result studied by the Langton et al. (2023) review: estimates of individual financial fraud in other data sources range widely (and may include differences in defining covered fraud types), but the SFS’s estimate of 1.2 percent of persons age 18 or older experiencing financial fraud in 2017 seems small relative to other reported estimates. That said, another round of the SFS is reported to be forthcoming at the time of this writing.

Cyberstalking and the Supplemental Victimization Survey

The Office on Violence Against Women sponsored the first Supplemental Victimization Survey (SVS) to the NCVS in 2006 to measure stalking, and the supplement has since been administered in 2016 and 2019. The best way to portray the crime content and basic approach of the SVS is to review the first (screener) question on the instrument that the NCVS/SVS interviewer reads to any NCVS respondent age 16 or older (see Box 2-4).11 The first notable feature of the question is that it spells out a detailed 12-part classification of types of stalking behaviors—incidences and consequences of which are discussed in the rest of the survey—without actually using the word “stalking” to avoid any unwanted connotations or instinctual reactions. Second, the embedded classification of stalking behaviors has two higher-level categories. Responses a–f are “traditional,” mainly physical stalking behaviors, including direct physical surveillance, while responses g–l all fall under the general heading of “stalking with technology.” The report on the outcomes of the 2019 SVS emphasizes that cyberstalking (as defined in federal law; see Appendix C) and stalking with technology are very close in concept but not identical—the essential difference being that the text messages clause in Box 2-4 item g would likely be covered

___________________

10 See https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/sfs_2017.pdf

11 The minimum response age was lowered from 18 to 16 for the second and subsequent administrations of the SVS.

BOX 2-4

Question 1, Types of Stalking Behaviors Measured, Supplemental Victimization Survey, 2019

Now, I would like to ask you some questions about the times when you may have experienced unwanted contacts or behaviors. I want to remind you that the information you provide is confidential. When answering, please think about anyone who may have done these things, including current or former spouses or partners, other people you may know, or strangers. However, please DO NOT include bill collectors, solicitors, or other sales people.

SQ1. In the past 12 months, have you experienced any unwanted contacts or behaviors? By that I mean . . .

- Has anyone followed you around and watched you?

- Has anyone snuck into your home, car, or any place else and done unwanted things to let you know they had been there?

- Has anyone waited for you at home, work, school, or any place else when you didn’t want them to?

Still thinking about unwanted contacts and behaviors, in the past 12 months . . .

- Has anyone shown up, ridden or driven by places where you were when they had no business being there?

- Has anyone left or sent unwanted items, such as cards, letters, presents, flowers, or any other unwanted items?

- Has anyone harassed or repeatedly asked your friends or family for information about you or your whereabouts?

by definitions of cyberstalking, but the pure telephone and voice message contact modes in item g might not (Morgan & Truman, 2019, p. 3).

Federal law describes two other essential elements to the definition of stalking/cyberstalking (18 U.S.C. § 2261A(2); see Appendix C), and incorporating these elements affects the way the SVS proceeds. First, like the general offense of harassment, stalking/cyberstalking is a repeated-course-of-conduct offense, meaning that a single instance of the stalking behaviors in Box 2-4 does not constitute a stalking/cyberstalking offense; there must be two or more instances.12 Second, the course-of-conduct actions must produce either actual fear (i.e., substantial emotional distress) or reasonable fear (i.e., threatened or completed attack on the victim, someone close to the victim, or a pet, sufficient to cause fear for their safety). In administrations to date, the SVS has taken a slightly unusual approach to the course-of-conduct problem,

___________________

12 This is the case even with the plural forms of key nouns in the Box 2-4 options, such as the “phone calls” and “text messages” of option g and “e-mails or messages” of option k.

Now I want to ask about unwanted contacts and behaviors using various technologies, such as your phone, the Internet, or social media apps. Again, please DO NOT include bill collectors, solicitors, or other unwanted sales people. In the past 12 months . . .

- Has anyone made unwanted phone calls to you, left voice messages, sent text messages, or used the phone excessively to contact you?

- Has anyone spied on you or monitored your activities using technologies such as a listening device, camera, or computer or cell phone monitoring software?

Still thinking about unwanted contacts and behaviors, in the past 12 months . . .

- Has anyone tracked your whereabout with an electronic tracking device or application, such as GPS or an application on your cell phone?

- Has anyone posted or threatened to post inappropriate, unwanted, or personal information about you on the Internet, including private photographs, videos, or spreading rumors?

- Has anyone sent you unwanted e-mails or messages using the Internet, for example, using social media apps or websites like Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook?

- Has anyone monitored your activities using social media apps like Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook?

SOURCE: Excerpted (less variable names and Yes/No response boxes to each question) from 2019 Supplemental Victimization Survey questionnaire, https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/svs_19.pdf

defined as the repeated occurrence of one of the specific stalking behaviors depicted in Box 2-4 (as determined by a follow-up question if only one “Yes” response is received) or the occurrence of multiple stalking behaviors (Morgan & Truman, 2019, p. 3). The SVS asks a follow-up question as to whether any of the experienced stalking behaviors caused actual fear and, similarly, whether any caused reasonable fear. If the course of conduct and either actual or reasonable fear are established, the respondent is queried about the details of the incident, including knowledge of the offender(s), purported motive, and whether the incident was reported to authorities.

Cyberbullying and the School Crime Supplement

The recurring SCS to the NCVS is the product of a long-standing partnership between the BJS and the National Center for Education Statistics in the U.S. Department of Education. The SCS, which has been administered on a roughly biennial cycle since 1999 (and fielded twice previously in 1989

and 1995), has always included some content related to bullying. The SCS bullying content was revised in the 2005 administration of the supplement, to ask about bullying behaviors in a manner more consistent with definitions under joint development by the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Gladden et al., 2014).13 Though some bullying behaviors mentioned in earlier versions of the SCS could arguably be carried out by electronic/computer means, it was not until the 2022 SCS that changes were made aiming to better capture cyberbullying (or electronic bullying, as it is labeled by Gladden et al. [2014]). These changes included revising the introduction to the main bullying question to say that “these [unwanted behaviors] could occur in person or using technologies, such as a phone, the Internet, or social media”14 and the addition of a separate category for “purposely shared your private information, photos, or videos in a hurtful way.”15 Note, however, that the changes served to capture more electronic bullying behavior but did not necessarily distinguish it from conventional bullying; the distinction remains murky in that some of the other bullying behaviors (e.g., “made fun of you, called you names, or insulted you in a hurtful way” or “spread rumors about you”) could occur by either electronic or nonelectronic means. The results of the most recent administration of the SCS, in 2022, are summarized by Irvin et al. (2024).

Two general points about bullying and cyberbullying are worthy of brief mention in the context of current data sources. First, bullying is necessarily a difficult concept for national crime statistics because there is wide variation in the degree to which the states classify and consider bullying a crime in their penal or criminal codes, as opposed to regulating the behavior under the state’s education code. Likewise, there is variation in the ways in which cyberbullying—if called out specifically in state law—is handled, though some states directly criminalize cyberbullying because of the potential for adults to perform the bullying actions while posing as

___________________

13 Prior to deployment, the questions were cognitively tested by U.S. Census Bureau staff (Pascale et al., 2014).

14 Previously, as in the 2019 version of the SCS, a question about where the bullying incidents occurred listed “Online or by text” as a response option; see https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/survey/2019_scs.pdf. The location question was not asked in the 2022 questionnaire, part of broadening the supplement’s scope from the traditional “at school” to the more inclusive “during school.”

15 See https://bjs.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh236/files/media/survey/2022_scs.pdf. Another category/response in the main bullying question, number 22 on the questionnaire, makes explicit mention of social media: “excluded you from activities, social media, or other communications to hurt you.”

juveniles on social media and electronic forums.16 Second, as types of behavior that straddle the line between criminal and education/civil law, bullying and cyberbullying are covered to some extent in other educational and public health data surveillance systems, including the Youth Risk Behavior Survey coordinated by the CDC, the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Survey coordinated by the World Health Organization, and the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence jointly sponsored by the U.S. Department of Justice and the CDC (National Academies, 2016b).

Cybercrime Against Businesses, and the National Computer Security Survey

For purposes of measuring cybercrime, the major drawback of the NCVS and its supplements is that, being household surveys, they only examine offenses against survey respondents—individual persons, not businesses or organizations. This was not always the case, however. As described in more detail by the National Research Council (2008), the NCVS began in 1972 as the National Crime Surveys—plural—and included two commercial components, a national sample of 15,000 businesses and targeted samples of 2,000 businesses in 26 cities (data were only collected from eight of the focus cities at a time). However, an early review by an even more distant predecessor of our panel (National Research Council, 1976) recommended that city-specific sampling be stopped in favor of boosting the national sample size of the household crime survey and also advised that the commercial victimization survey be suspended and reassessed. Combined with budgetary reasons and perceived inadequacy of the business sampling frame then in use, the commercial victimization component of the National Crime Surveys was eliminated shortly thereafter.

Interest in commercial victimization has resurfaced over the years, and the emergence of cybercrime spurred particular attention. In 2001, a second effort to measure crimes against businesses was cosponsored by the BJS and the National Cyber Security Division of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (USDHS); RAND was engaged as the data-collection agent, and the

___________________

16 For example, Louisiana Revised Statute 14:40.7 (added in 2010, revised 2019; Title 14 is Criminal Law) defines cyberbullying—“transmission of any electronic textual, visual, written, or oral communication with the malicious and willful intent to coerce, abuse, torment, or intimidate a person under the age of eighteen”—as a crime, punishable by fine or imprisonment when the offender is an adult but “governed exclusively by Title VII of the Children’s Code” (i.e., the juvenile justice system) when the offender is under age 18. This overlaps with more wide-ranging anti-bullying laws enacted in 2022 and 2024 (Louisiana RS 17:416.14, Title 17 being the Education title of the statutes), including more detailed definitions and “electronic communication” as a means of bullying, but focused on establishing comprehensive policy within school districts rather than criminal sanctions for the offense.

survey was conducted first as a pilot and then in full in 2005. This effort, dubbed the National Computer Security Survey (NCSS), was developed to measure the nature and extent of computer security incidents, monetary costs, and other consequences. The specific types of incidents covered by the NCSS are shown in Box 2-5, and Box 2-6 shows that the NCSS also asked responding companies and organizations why incidents were or were not reported to law enforcement or other authorities. The survey collected data from 7,818 businesses. Although 67 percent of responding businesses detected cybercrime in 2005, most businesses did not report cyberattacks to law enforcement (Rantala, 2008).

Though the NCSS remains listed on the BJS’s website as an active program, it has not been fielded since the single instance in 2005, possibly owing to a lower-than-expected response rate (23%) in the initial administration (Rantala, 2008, p. 15).

BOX 2-5

Types of Computer Security Incidents Covered by 2005 National Computer Security Survey

Cyber attack

- Computer virus—defined as “a hidden fragment of computer code which propagates by inserting itself into or modifying other programs.” Meant to include worms, trojan horses, etc., but not spyware, adware, or other malware (which are to be included as “other computer security incidents”).

- Denial of service—defined as “the disruption, degradation, or exhaustion of an Internet connection or e-mail service that results in an interruption of the normal flow of information. Denial of service is usually caused by ping attacks, port scanning probes, excessive amounts of incoming data, etc.”

- Electronic vandalism or sabotage—defined as “the deliberate or malicious damage, defacement, destruction or other alteration of electronic files, data, web pages, programs, etc.”

Cyber theft

- Embezzlement—defined as “the unlawful misappropriation of money or other things of value, BY THE PERSON TO WHOM IT WAS ENTRUSTED (typically an employee), for his/her own use or purpose. INCLUDE instances in which a computer was used to wrongfully transfer, counterfeit, forge or gain access to money, property, financial documents, insurance policies, deeds, use of rental cars, various services, etc., by the person to whom it was entrusted.”

OTHER ENTITIES COLLECTING CYBERCRIME-RELATED DATA, PARTICULARLY FRAUD

Internet Crime Complaint Center

The FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) was originally founded as the Internet Fraud Complaint Center in 2000, adopting the current name and a broader focus in 2003. The IC3 primarily functions as an avenue for receiving complaints of internet-facilitated and internet-related crimes from the public. IC3 analysts assess the public reports for validity (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2023). Commonly, the relevant financial institution is contacted (i.e., to ensure that no further harm has been done to the victim’s account); the incident is also referred to the appropriate FBI field office, if necessary, for further

- Fraud—defined as “the intentional misrepresentation of information or identity to deceive others, the unlawful use of credit/debit card or ATM or the use of electronic means to transmit deceptive information, in order to obtain money or other things of value. Fraud may be committed by someone inside or outside the company. INCLUDE instances in which a computer was used by someone inside or outside this company in order to defraud this company of money, property, financial documents, insurance policies, deeds, use of rental cars, various services, etc., by means of forgery, misrepresented identity, credit card or wire fraud, etc.”

- Theft of intellectual property—defined as “the illegal obtaining of copyrighted or patented material, trade secrets, or trademarks including designs, plans, blueprints, codes, computer programs, software, formulas, recipes, graphics, etc., usually by electronic copying.”

- Theft of personal or financial data—defined as “the illegal obtaining of information that could potentially allow someone to use or create accounts under another name (individual, business, or some other entity). Personal information includes names, dates of birth, social security numbers, etc. Financial information includes credit/debit/ATM card, account, or PIN numbers, etc.”

Other computer security incidents—to include “all other computer security incidents involving this company’s computer networks—such as hacking, sniffing, spyware, theft of other information—regardless of whether damage or losses were sustained as a result.”

SOURCES: Panel generated from survey questionnaire at https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/ncss_1.pdf and Davis et al. (2008).

BOX 2-6

Response Options on Reporting and Nonreporting of Computer Security Incidents, 2005 National Computer Security Survey

To which of the following organizations were these incidents reported? Mark all that apply.

- Local law enforcement

- State law enforcement

- FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation)

- US-CERT (United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team)

- CERT® Coordination Center

- Other federal agency (Specify)

- ISAC (Information Sharing and Analysis Center)

- InfraGard

- None of the above

If any incidents were not reported to the organizations specified [above], what were the reasons? Mark all that apply.

- Handled internally

- Reported to third-party contractor providing computer security services

- Reported to another organization (Specify)

- Negative publicity

- Lower customer/client/investor confidence

- Competitor advantage

- Did not want data/hardware seized as evidence

- Did not know who to contact

- Incident outside jurisdiction of law enforcement

- Did not think to report

- Nothing to be gained/nothing worth pursuing

- Other (Specify)

NOTE: Question text excerpted from section of questions related to occurrences of fraud, but similar/identical wording applies to other incident types. SOURCES: Panel generated from survey questionnaire at https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/ncss_1.pdf and Davis et al. (2008).

investigation (Quigley, 2024). Complaints are submitted through the IC3 Network, which includes an online complaint referral form and an associated database of complaint information. The complaint form itself does not require the respondent to categorize the incident as a crime/cybercrime directly, but it provides an open-text field for response that analysts can fill in, based on the data provided, to classify the incident by type. An annual report (e.g., Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2023c,

2024) summarizes the number and geographical distribution of reported offenses, along with an estimate of the monetary losses incurred through the offenses. In 2023, IC3 received 880,418 complaints amounting to losses totaling $12.5 billion (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2024).

The annual reports regularly contain a table showing reported offenses within the past three years; four years of these three-year tables are combined in Table 2-5 to convey the range of offenses covered by the IC3 and shifts in their categorization over time. Numerous variants of fraud (labeled by the purported benefit in the fraud) dominate the listings in IC3’s reports, befitting the organization’s original name, but other cybercrime types (e.g., ransomware, crimes against children, and harassment/stalking) are reported to IC3 by the public and hence show up in IC3 annual reports. There is no apparent underlying structure to the IC3’s list of covered offenses, save that it shifts slightly from year to year and is revised based on changes in frequency of particular groups of offenses.

Federal Trade Commission’s Consumer Sentinel Network

The FTC’s Consumer Sentinel Network is a centralized database and repository for customer complaint data. While the IC3, initially established to monitor internet fraud, has expanded its scope to include other types of cybercrime, the FTC’s collection remains focused, in extensive detail, on crimes of fraud and identity theft as well as related scams and bad business practices. The same law that defined the federal offense of identity theft (P.L. 105-318; see Appendix C) defined the FTC as the “centralized complaint and consumer education service for victims of identity theft,” directing the FTC to “log and acknowledge” consumer complaints and to refer them to credit reporting agencies and law enforcement agencies as appropriate. The Consumer Sentinel Network database is populated by reports from the public through its online portal, but also extensively through data provided by other contributors (e.g., the IC3, the Better Business Bureau, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and state attorneys general). In 2023, the FTC collected 2.6 million reports classified as fraud, with $10.3 billion in reported losses (Fletcher, 2024). Box 2-7 shows the top-level report categories defined in the Consumer Sentinel Network, including 17 categories for fraud and seven categories for identity theft, all based on the good or service the offender is attempting to collect through the fraud or identity theft. The companion list of Consumer Sentinel Network report subcategories17 defines a pool of 97 goods, services, or other objectives of fraudulent activity. There is inherent fluidity to these categorizations; in discussion with the

___________________

17 See https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/CSNPSCFullDescriptions.pdf

| Victim Count | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offense | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 |

| Advanced Fee | 8,045 | 11,264 | 11,034 | 13,020 | 14,607 | 16,362 |

| BECa | 21,489 | 21,832 | 19,954 | 19,369 | 23,775 | 20,373 |

| Botnet | 540 | 568 | — | — | — | — |

| Charity | — | — | — | 659 | 407 | 493 |

| Civil Matter | — | — | 1,118 | 968 | 908 | 768 |

| Confidence Fraud/Romance | 17,823 | 19,021 | 24,299 | 23,751 | 19,473 | 18,493 |

| Corporate Data Breach | — | — | 1,287 | 2,794 | 1,795 | 2,480 |

| Credit Card/Check Fraudb | 13,718 | 22,985 | 16,750 | 17,614 | 14,378 | 15,210 |

| Crimes Against Children | 2,361 | 2,587 | 2,167 | 3,202 | 1,312 | 1,394 |

| Data Breach | 3,727 | 2,795 | 1,287 | 2,794 | — | — |

| Denial of Service/TDoS | — | — | 1,104 | 2,018 | 1,353 | 1,799 |

| Employment | 15,443 | 14,946 | 15,253 | 16,879 | 14,493 | 14,979 |

| Extortion | 48,223 | 39,416 | 39,360 | 76,741 | 43,101 | 51,146 |

| Gambling | — | — | 395 | 391 | 262 | 181 |

| Government Impersonation | 14,190 | 11,554 | 11,335 | 12,827 | 13,973 | 10,978 |

| Hacktivist | — | — | — | 52 | 39 | 77 |

| Health Care Related | — | — | 578 | 1,383 | 657 | 337 |

| Identity Theft | 19,778 | 27,922 | 51,629 | 43,330 | 16,053 | 16,128 |

| Investment | 39,570 | 30,529 | 20,561 | 8,788 | 3,999 | 3,693 |

| IPR/Copyright and Counterfeit | 1,498 | 2,183 | 4,270 | 4,213 | 3,892 | 2,249 |

| Lottery/Sweepstakes/Inheritance | 4,168 | 5,650 | 5,991 | 8,501 | 7,767 | 7,146 |

| Malwarec | 659 | 762 | 810 | 1,423 | 2,373 | 2,811 |

| Misrepresentation | — | — | — | 24,276 | 5,975 | 5,959 |

| Victim Count | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offense | 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 |

| Non-Payment/Non-Delivery | 50,523 | 51,679 | 82,478 | 108,869 | 61,832 | 65,116 |

| Other | 8,808 | 9,966 | 12,346 | 10,372 | 10,842 | 10,826 |

| Overpayment | 4,144 | 6,183 | 6,108 | 10,988 | 15,395 | 15,512 |

| Personal Data Breach | 55,851 | 58,859 | 51,829 | 45,330 | 38,218 | 50,642 |

| Phishing/Spoofing | 298,878 | 321,136 | 342,494 | 269,560 | 140,491 | 41,948 |

| Phishingd | — | 300,497 | 323,972 | 241,342 | 114,702 | 26,379 |

| Spoofing | — | 20,649 | 18,522 | 28,218 | 25,789 | 15,569 |

| Ransomware | 2,825 | 2,385 | 3,729 | 2,474 | 2,047 | 1,493 |

| Real Estatee | 9,521 | 11,727 | 11,578 | 13,638 | 11,677 | 11,300 |

| Re-Shipping | — | — | 516 | 883 | 929 | 907 |

| SIM Swap | 1,075 | 2,026 | — | — | — | — |

| Tech Support | 37,560 | 32,538 | 23,903 | 15,421 | 13,633 | 14,408 |

| Harassment/Stalking | 9,587 | 11,779 | — | — | — | — |

| Threats of Violence | 1,697 | 2,224 | — | — | — | — |

| Terrorism/Threats of Violence | — | — | 12,346 | 20,669 | 15,563 | — |

| Harassment/Threats of Violence | — | — | — | 20,604 | 15,502 | 18,415 |

| Terrorism | — | — | — | 65 | 61 | 120 |

a Renamed BEC (Business Email Compromise) from BEC/EAC (latter meaning Email Account Compromise) in 2022 report.

b Check Fraud added to Credit Card Fraud in 2022 report.

c Renamed Malware from Malware/Scareware/Virus in 2022 report.

d Renamed Phishing from Phishing/Vishing/Smishing/Pharming in 2022 report.

e Renamed Real Estate from Real Estate/Rental in 2020 report.

NOTES: —, category not used in reporting year; IPR, intellectual property rights; TDoS, Telephony Denial of Service. Rows indicating the separate handling of harassment, terrorism, and threats of violence are grouped at the end, out of alphabetical order, for ease of comparison. The only added calculations are the italicized entries for Phishing/Spoofing in 2018, summing the individual Phishing and Spoofing entries because the two offense types were not previously reported as a combined sum.

SOURCES: Panel generated from “Last-Three-Year Complaint Comparison” table in Internet Crime Report issues for 2020–2023 (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2021, 2022, 2023c, 2024).

BOX 2-7

Report Categories in the Federal Trade Commission Consumer Sentinel Network

Fraud

- Advance Payments for Credit Services

- Business and Job Opportunities

- Charitable Solicitations

- Foreign Money Offers and Fake Check Scams

- Grants

- Health Care

- Imposter Scams

- Internet Services

- Investment Related

- Magazines and Books

- Mortgage Foreclosure Relief and Debt Management

- Office Supplies and Services

- Online Shopping and Negative Reviews

- Prizes, Sweepstakes and Lotteries

- Tax Preparers

- Telephone and Mobile Services

- Travel, Vacations and Timeshare Plans

Identity Theft

- Bank account

- Credit Card

panel, Fletcher (2024) included Miscellaneous Reports and Unspecified Reports—as well as the Privacy, Data Security, and Cyber Threat report category (through which the FTC receives some reports and complaints about general cybercrime)—as types of fraud, identifying 47 subcategories. This fluidity is meant to keep FTC’s taxonomy of report types as an evolving system, with categories and subcategories created and collapsed over time based on the data being reported and permitting focus on emerging areas/issues of interest. Fletcher (2024) noted that categorization based on the type of good or service at issue avoids the definition of categories based on demographics, contact methods, and monetary loss—so, for instance, reports are not classified as “elder fraud,” “phone scams,” or “high-loss fraud”; however, that information is collected in the data series, which generally enables distinguishing between cybercrime- and noncybercrime-related instances. The code list of report categories is periodically reviewed; members of the public making reports to the FTC are asked to self-select a category, or one may be assigned by staff (e.g.,

- Employment and/or Tax-Related

- Government Documents or Benefits

- Loan or Lease

- Phone or Utilities

- Other Identity Theft

Other Report Categories

- Auto Related

- Banks and Lenders

- Computer Equipment and Software

- Credit Bureaus, Information Furnishers and Report Users

- Credit Cards and Loss Protection

- Debt Collection

- Education

- Funeral Services

- Home Repair, Improvement and Products

- Privacy, Data Security, and Cyber Threats—“Reports about data privacy, including children’s online privacy. This includes reports about the collection, storage, use, disclosure, or disposal of consumer data. Also included are reports about malware and computer exploits, including spyware, malware, denial of service attacks, etc.”

- Television and Electronic Media

SOURCE: Consumer Sentinel Network Descriptions of Report Categories, at https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/attachments/data-sets/category_definitions.pdf

through rules-based classification), and the FTC works to crosswalk its classification scheme with those of its data contributors.

Other Entities

Cyber-involved fraud is so ubiquitous and widespread that many other agencies and organizations are working in the field, among them AARP’s Fraud Watch Network, the Better Business Bureau, and the Identity Theft Resource Center. For instance, AARP’s Fraud Watch Network operates a free helpline, through which all members of the public can report incidents of fraud and receive support from trained volunteers. Reports made through the helpline are sent to the FTC’s Consumer Sentinel Network database (described earlier in this chapter). AARP’s Fraud Watch Network receives roughly 100,000 reports annually and approximately 300–500 calls per day (Fetterhoff, 2024). In 2024, victim reports to the helpline included identity theft; impostor business; tech support and computer viruses; fraudulent

sales; online dating and romance schemes; impostor government schemes; sweepstakes, prize, or lottery schemes; unauthorized money withdrawal; investment fraud and schemes; and phishing (Fetterhoff, 2024). However, the AARP’s focus is understandably less on data collection and analysis and more on providing fraud victims with an empathetic ear and necessary information services.

As the U.S. Government Accountability Office (2023) report observed, and as noted by our predecessor Panel on Modernizing the Nation’s Crime Statistics, other law enforcement agencies (e.g., Homeland Security Investigations and the U.S. Postal Inspection Service) and information reporting/surveillance systems (e.g., the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network of the U.S. Department of the Treasury) gather information about incidents that may constitute cybercrime, but still operate outside the existing national crime statistics apparatus.

COLLECTION OF CYBERSECURITY INCIDENT INFORMATION AND CYBERCRIME-RELATED INFORMATION FROM BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY

Trusted Entities and Information Sharing Safe-Havens: Information Sharing and Analysis Centers/Organizations and the National Cyber-Forensics and Training Alliance