Examining Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor (GLP-1R) Agonists for Central Nervous System Disorders: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 4 Ingestive Behavior Disorders

4

Ingestive Behavior Disorders

HIGHLIGHTS

- Eating disorders are behavioral illnesses, not a matter of lifestyle choice. (Richardson)

- Preclinical and clinical evidence indicate that GLP-1R agonists could be an effective treatment for binge eating disorder and perhaps other eating disorders. (McElroy, Mietlicki-Baase, Richardson)

- GLP-1R agonists affect the behavior of dopamine neurons in the brain’s reward regions, but the precise mechanisms remain unclear. Understanding them better could lead to insights into how GLP-1R agonists affect ingestive behavior disorders, such as binge eating. (Davis)

- One of the challenges for understanding the biological processes and changes in the GLP-1 signaling in the context of eating disorders is a shortage of funding opportunities for basic science or mechanistic studies in this area. (Mietlicki-Baase)

NOTE: This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of points made by the individual speakers identified, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Kimberlei Richardson said there is a common misconception that eating disorders are a matter of lifestyle choice, but, according to both the American Psychiatric Association and the National Institute of Mental Health, eating disorders are behavioral illnesses characterized by severe and persistent disturbance in eating behaviors and associated with distressing thoughts and emotions. The most common eating disorders are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder, she said, and approximately 9 percent of Americans, or 28.8 million people today, will have an eating disorder in their lifetime, and some 10,200 Americans die each year as a direct result of an eating disorder (Deloitte Access Economics, 2020). An estimated 42–52 percent of individuals diagnosed with binge eating disorder have a reported comorbidity of obesity, which increases the risk of mortality (Agüera et al., 2021; Udo and Grilo, 2018; Villarejo et al., 2012).

Significant evidence has been accumulated that GLP-1R agonists may be effective in treating such ingestive behavior disorders, Richardson said. For instance, a number of preclinical studies have indicated that these agonists play a role in regulating feeding and binge eating behaviors (Barrera et al., 2011; Holt et al., 2019; Mietlicki-Baase et al., 2013; Yamaguchi et al., 2017). There have also been clinical studies investigating the effect of GLP-1R agonists on binge eating behavior. In one, individuals treated with liraglutide demonstrated reduced binge eating behavior and lost more weight than those not treated with the drug (Robert et al., 2015). In another, GLP-1R agonists showed promising results in treating binge-eating behavior, though more rigorous clinical trials will be needed (Aoun et al., 2024).

Richardson concluded by listing the session objectives: (1) to review current knowledge about the mechanism of action of GLP-1R agonists and their therapeutic applications in ingestive behaviors, (2) to discuss the available scientific evidence of the clinical efficacy of these drugs for treating eating disorders, (3) to discuss the clinical consequences and adverse effects related to the use of GLP-1R agonists, and (4) to identify unique gaps and challenges in the field and provide suggestions for future research.

GLP-1R AGONISTS AND EATING DISORDERS

Susan L. McElroy, chief research officer at the Lindner Center of HOPE and Linda and Harry Fath Endowed Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, reviewed clinical evidence concerning the effectiveness of GLP-1R agonists in treating various eating disorders.

She began by listing all the feeding and eating disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition. The most common eating disorder is binge eating disorder, she said, and it is strongly

associated with obesity. Bulimia nervosa is also associated with obesity, as is atypical anorexia nervosa, where people have all the psychological symptoms of anorexia but are normal weight, overweight, or obese.

There are also several disorders not listed in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders that are associated with obesity but that researchers really need to learn more about, she added. These include food addiction, which has a strong overlap with binge eating disorder, antipsychotic-induced binge eating, and hyperphagia and polyphagia, which are types of intense overeating observed with monogenetic obesity, that is, obesity caused by a mutation in a single gene.

Of all of these, she said, binge eating disorder has been the focus of the most scientific research. A number of drugs have been used in clinical trials to treat binge eating disorder. Four of them are on the market—bupropionnaltrexone, liraglutide, orlistat, and phentermine-topiramate—but none of these four have clear evidence of effectiveness in treating binge eating. Orlistat, for example, has shown positive results for weight loss but mixed results for binge eating (McElroy et al., 2012).

At least two studies have focused on the effects of liraglutide in people with binge eating and who are overweight. In one, 44 patients were randomly assigned to liraglutide or treatment as usual. According to the Binge Eating Scale, a self-report measure of binge eating symptomatology, there was a significant reduction in binge eating in both groups. However, only the liraglutide group showed a significant weight loss and reduction in body mass index (Robert et al., 2015).

The only randomized controlled trial of liraglutide for the treatment of binge eating disorder that McElroy was aware of was a small pilot study with 27 individuals who were given either liraglutide or a placebo for 17 weeks (Allison et al., 2022). Again, only the liraglutide group showed weight loss, while both groups had a reduction in the number of binge eating episodes per week over the course of the experiment.

The reduction in binge eating in the control groups of the two experiments was not unusual, McElroy said, as researchers regularly see a placebo response in binge eating disorder, and they have now identified ways to conduct clinical trials to minimize that. Given the small numbers of participants and the existence of a placebo effect, both studies have limitations, she said, but they do suggest that liraglutide reduces binge eating in addition to reducing weight. Furthermore, the drug has been shown to be safe, making it a good candidate for treating binge eating, she added.

Finally, McElroy described a study that her group carried out in patients with stable bipolar disorder and obesity. Many mental illnesses are associated with obesity, including bipolar disorder, she noted, so such studies are important. It was a 40-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, and the majority of these patients were on antipsychotics. Despite that,

the patients given liraglutide had a marked decrease in weight (McElroy et al., 2024). Her team also carefully evaluated the patients for psychiatric side effects, including suicidality using the Columbia suicide scale,1 and found no indication that liraglutide increased suicidality or caused mood instability—a concern with several other weight loss drugs. In addition, the team assessed binge eating behavior using the Binge Eating Scale and found that liraglutide significantly reduced binge eating behavior while also reducing hunger.

Finally, she said that her team prescribes GLP-1R agonists to some patients diagnosed with obesity and an eating disorder. They believe that there are preliminary data to suggest these compounds may be helpful in treating binge eating disorder, including binge eating disorder induced by antipsychotic medication and binge eating disorder in people who are of normal weight. They also believe that the compounds might be helpful for some people with bulimia nervosa, especially those who also have obesity. She warned, however, that GLP-1R agonists could be misused by people with anorexia nervosa in their efforts to lose weight.

McElroy said that when people with obesity come to her center for treatment, the clinicians evaluate them very carefully for eating disorders as well as other psychiatric disorders. “There is no doubt obesity and psychiatric disorders are related,” she concluded, “and I think that’s been a completely ignored area.”

THE RESPONSE OF THE BRAIN’S REWARD REGIONS TO GLP-1R AGONISTS

Jon Davis spoke about research on how GLP-1R agonists affect dopaminergic neurons in the central nervous system, which are intimately involved with reward-seeking behavior.

He began by reviewing some clinical data from Novo Nordisk’s STEP (Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with Obesity) trial. Patients treated with 2.4 milligrams of semaglutide lost an average of about 16 percent of their body weight over 60 weeks, although there was a plateau around 52 weeks after which they lost little more weight. Then, after patients were removed from the drug, they regained an average of about 10 percent of their original body weight over the next 60 weeks, leaving them at about 6 percent down from their weight at the beginning of the trial (Wilding et al., 2022).

___________________

1 “The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) is a short questionnaire that can be administered quickly in the field by responders with no formal mental health training, and it is relevant in a wide range of settings and for individuals of all ages.” https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/dbhis/columbia-suicide-severity-rating-scale-c-ssrs (accessed November 10, 2024).

Given these results, Davis said, researchers at Novo Nordisk were interested in what leads to the plateau in weight loss and what leads to the weight regain once patients stop taking semaglutide. One interesting result, he added, related to how long-term use of a GLP-1R agonist affects the reward regions in the CNS. Novo Nordisk scientists gave patients a 3-mil-ligram dose of liraglutide—the highest dose approved for weight loss—for 35 weeks and examined their brains’ response to palatable food cues. What they found was that reward regions in the orbital frontal cortex, when corrected for body mass index, responded more strongly to the food cues after the 35 weeks of liraglutide than they had before. These were patients who had lost a significant amount of weight, he said, but their brains’ reward regions were reacting more strongly than before. “This would not be what we would predict,” he said, as patients who have been treated for many months with a GLP-1R agonist generally report having less appetite and interest in food.

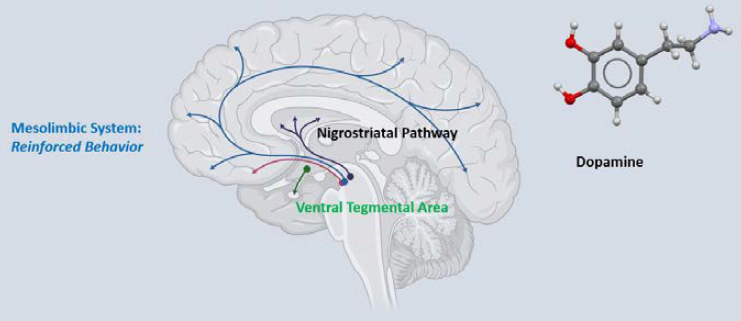

To explore potential mechanisms, the researchers took a closer look at the response of the brain’s reward regions—particularly its dopamine system—to GLP-1R agonists. He showed a diagram of the brain’s mesolimbic dopamine system, with a specific focus on the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and its projections to the nucleus accumbens as well as to the frontal cortex (see Figure 4-1). Over the past 50 to 60 years, Davis said, this system has been intensely studied for its ability to regulate substance use disorder as well as reward-based learning and reinforcement learning, but in the past 20 years it has become clear that this process controls appetite as well. And it turns out that GLP-1R agonists and other incretins (gastrointestinal hormones that regulate insulin secretion) modulate this mesolimbic dopamine system. Generally speaking, Davis explained, things that increase dopamine

NOTE: CNS = central nervous system.

SOURCE: Presented by Jon Davis on September 10, 2024.

levels motivate behaviors, while things that decrease dopamine levels do the opposite.

So how do GLP-1R agonists affect dopamine levels in this system? In one study that examined this issue, researchers administered exendin-4, a GLP-1 agonist, directly into the lateral ventricle of rats to see what happened to the activity of dopamine neurons in the VTA. The key result, Davis said, is that when the drug was administered, it not only reduced anticipation and consumption of palatable foods in the rats, but it also decreased the activity of dopamine neurons (Konanur et al., 2020). One might assume, then, that triggering GLP-1 receptors in the rodent brain has its effect on appetite and body weight by reducing the activity of dopamine neurons, he said. However, it is not that simple, as a similar study had very different results. In that study, mice were given semaglutide in their abdominal cavity, and its effects on appetite and dopamine signaling in the VTA were studied. Again, the animals showed decreased appetite and lost weight, but there was an increase in the activity of dopamine neurons (Kooij et al., 2024).

The differences between the two studies could be the dose used or the particular GLP-1R agonist that was administered, Davis said. It could also be the method of administration, either directly into the CNS or in the periphery, which would involve crossing the blood–brain barrier. “It is not clear at this point actually what’s going on with how these drugs are activating or engaging with the dopamine system,” he said.

Thus, he concluded, more studies are needed clarify exactly how the brain monoamine system is affected by GLP-1R agonists.

BINGE EATING AND THE ENDOGENOUS GLP-1 SYSTEM

Elizabeth Mietlicki-Baase, associate professor in the Department of Exercise and Nutrition Sciences at the University of Buffalo, spoke about studies in lab animals aimed at understanding how binge eating may affect GLP-1 expression in the brain and whether GLP-1R agonists might be a potential treatment for binge eating.

She began by defining binge eating as consuming a larger than normal amount of food in a discrete period of time. According to data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication in 2001–2003, the lifetime prevalence of binge eating behavior in the United States is 4.9 percent for women and 4.0 percent for men (Hudson et al., 2007), and binge eating is associated with obesity and other comorbidities. Furthermore, Mietlicki-Baase added, binge eating is not limited to those people with diagnosed eating disorder. “Plenty of people might binge eat,” she said. “It just doesn’t reach clinical diagnosis level. So, this is a problem that affects a lot of people.”

The current treatment options for binge eating disorder are limited, she said. They include evidence-based psychological treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy; lisdexamfetamine, which is a psychostimulant drug approved by the FDA for the treatment of binge eating disorder; and some off-label uses of pharmacotherapies. Given those limited options, Mietlicki-Baase became interested in GLP-1 as a pharmacological target that might point to a more effective treatment of the disorder (Balantekin et al., 2024; McElroy et al., 2018).

She and her team focused their attention on the nucleus of the solitary tract (NST), which produces preproglucagon, the precursor to GLP-1, and which has direct projections to many areas of the brain—particularly areas relevant to food intake and food reward. Therefore, they hypothesized that binge eating in laboratory animals would lead to changes in GLP-1 expression in the hindbrain.

Binge eating is modeled in rodents by limiting the animals’ access to a particularly palatable food, such as vegetable shortening, so that they eat more of it than if they were given more regular access. Control animals might be given access to the palatable food for 1 hour every day, for instance, while the trial animals might get access for 1 hour on every other day. When those trial animals do get their access, they overeat, or “binge.” (The animals are all given as much water and regular rat chow as they want.) This is not the same as binge eating in humans, Mietlicki-Baase noted, since it is missing the various psychological aspects and cognitive aspects to the disorder that are present in people. But the overeating aspect is similar, and this intermittent provision of palatable foods is a standard model for binge eating in rats. Mietlicki-Baase referred to what the rats do as “binge-like eating” to acknowledge the differences.

Her group’s first study looked at whether binge-like eating affected GLP-1 expression in the NST of male rats. Some rats were given intermittent access to the palatable food, while the control group had regular access. After nine weeks, they collected tissue and blood samples from the animals and performed various measurements. There were no differences in body weight between the two groups, which was critical, she noted, because it let them look at the questions about central and peripheral GLP-1 in the absence of body weight changes that could act as a confounding factor.

Examining GLP-1 receptor expression in the NST, the researchers found no differences between the two groups of rats. However, the expression of the GLP-1 precursor, preproglucagon, in the NST was quite different, being drastically reduced in the rats with only intermittent access to feeding (Mukherjee et al., 2020). Her group interpreted this as the rats’ losing a signal that tells them to stop eating.

Interestingly, plasma GLP-1 was actually increased in the rats with intermittent access. Her group was puzzled by this, but they now think

it could be due to the rats anticipating the food. There is some evidence in the literature, she said, that rats on a scheduled access of feeding have anticipatory increases in circulating GLP-1.

Given the changes in the NST triggered by binge eating, Mietlicki-Baase wondered what other parts of the brain might be involved. They looked at the VTA, which Davis had described in the previous presentation as being an important part of the brain’s reward system. They found that, interestingly, GLP-1 receptor expression was increased in the VTA in the rats that had “binged.” Given that there seem to be various effects of binge-like eating on the GLP-1 system, she said, “we’re very interested in understanding whether increasing central GLP-1 signaling could be a strategy to ameliorate binge eating.”

To see whether there might be sex differences in how binge-like eating affects the GLP-1 system, Mietlicki-Baase’s group carried out a similar experiment on female rats. In this case they saw no difference between the intermittent access group and the control group in the expression of the preproglucagon in the NST, but they did see greater GLP-1 receptor expression in the NST in animals with free access to palatable food compared with a chow-only control group. There were no differences in plasma GLP-1 among the groups.

In terms of future directions and challenges in the area, Mietlicki-Baase highlighted several points. Given the differences they saw between males and females, her lab would like to further explore potential sex differences in binge eating and GLP-1. Furthermore, she added, “There is really a need to understand some of these key biological processes and changes in GLP-1 signaling in the context of binge eating and what the timing of these effects is. We did these studies after about 8 weeks of binge eating. We don’t know what happens earlier.”

Finally, she wishes to investigate the potential effects of other hormonal systems. “We know with the advent of dual- and tri-agonists and other hormonal systems being targeted for obesity treatment, there could be a more effective drug or combination therapy that we have yet to investigate,” she said.

As for challenges, she said that finding funding for further basic science research to understand the neurobiology of eating disorders is one of the biggest.

DISCUSSION

The Effect of GLP-1R on Dopamine

Brian Fiske asked if there have been any preclinical data on how GLP1R agonists affect dopamine specifically in the context of motor control,

which is important information for neurodegenerative diseases as Parkinson’s disease. Davis said he was not aware of research looking at phasic firing of the dopamine neurons and locomotion or other neurodegenerative-like endpoints. What has been done so far, he said, has focused just on appetite, food intake, and body weight endpoints.

In response to an online question about whether anyone has looked at the effects of GLP-1R agonists on dopaminergic neurons in the VTA in terms of slice preparations, Davis answered that Matthew Hayes and his lab have done a lot of work on that and have found that GLP-1 activity usually dampens the activity of the dopamine system. However, a recent report observed that administering semaglutide increased VTA dopamine signaling during reward collection (Kooij et al., 2024). “If you think about what would be clinically efficacious for safe body weight loss,” he said, “increasing dopamine might be the best way to go, so you don’t have to worry about anhedonia, you don’t have to worry about suicidal ideations.” Particularly, in the case of the FDA-approved anti-obesity drug bupropionnaltrexone, the reported mechanism of action is blocking dopamine transport, leading to more dopamine in the synapse. This does seem to indicate that increasing dopamine may be a safe and effective way to lower body weight, concluded Davis.

The Potential Benefits of Co-Agonists

Richardson asked Mietlicki-Baase for her thoughts on co-agonism—that is, the combining of two agonists—in the treatment of binge eating. Mietlicki-Baase began by speaking about the hurdles in getting funding for studies testing co-agonism strategies to reduce binge eating. “Especially the basic science mechanistic studies can be a challenge to find agencies that are willing to support that research,” she said regarding investigation of binge eating. “I think that that may improve as these dual- and tri-agonists and next generation drugs are shown to be effective in obesity treatment.” And, she continued, it is possible that the repurposing of dual- and tri-agonists toward binge eating disorder or bulimia nervosa might become a more attractive area of research to fund as more evidence appears. In particular, she pointed to amylin2 in combination with GLP-1R agonists such as semaglutide as having great promise in treating obesity and other disorders. Some preclinical work has been done to understand the role of amylin in binge eating, she said, and amylin seems to be affected in models of intermittent food access, but much more research needs to be done

___________________

2 Amylin is a peptide hormone secreted along with insulin from the beta cells in the pancreas. It plays a role in regulating both blood sugar and satiety.

before it will be possible to turn this work into a pharmaceutical treatment for binge eating.

Davis added that a great deal of preclinical work indicates that amylin is probably a stronger suppressor of palatable food intake than other GLP1R agonists, so amylin is a good molecule to be looking at for treatment of binge eating. More generally, he said that as more work is done with dual- and tri-agonists, he expects that there will be a greater focus on various obesity-related complications such as anxiety, depression, and binge eating, since the treatments will have the potential to address more than just obesity.

In sum, many workshop participants have shown that not only are GLP-1R agonists effective in treating obesity, but they have also shown promise against other eating disorders such as binge eating. Their effect on eating disorders seems to be at least partially dependent on their actions on dopamine neurons in the brain’s reward regions, though much more research is needed to understand exactly how they work.