Examining Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor (GLP-1R) Agonists for Central Nervous System Disorders: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 5 Substance Use Disorder and Alcohol Use Disorder

5

Substance Use Disorder and Alcohol Use Disorder

HIGHLIGHTS

- Preclinical and clinical evidence shows that GLP-1R agonists act to decrease drug use and seeking for a wide variety of substances including alcohol, nicotine, and opioids. (Farokhnia, Grigson, Jerlhag, Schmidt, Xu)

- GLP-1R agonists reduce alcohol consumption in rats, and a major reason for that effect seems to be that the agonists act on the brain’s dopamine system to block the rewarding properties of alcohol. (Jerlhag)

- Unlike GLP-1R agonists, DPP-4 inhibitors do not seem to have any effect on alcohol use, even though their action in the body is to increase the amount of GLP-1. (Farokhnia)

- The GLP-1R agonist exendin-4 has been shown to decrease drug-seeking behavior during withdrawal in rats that previously self-administered cocaine. (Schmidt)

- Exendin-4 seems to have its suppressive effect on drug seeking in rats at least in part by activating inhibitory GABA neurons, which in turn suppress dopamine cell activity in the VTA. (Schmidt)

- A small-scale clinical trial found that a GLP-1R agonist was effective in reducing craving for opioids among people with opioid use disorder. (Grigson)

- Trial emulations using real-world data indicate that semaglutide is effective against a number of substance use disorders, including alcohol use disorder, cannabis use disorder, tobacco use disorder, and opioid overdose risk. (Xu)

NOTE: This list is the rapporteurs’ summary of points made by the individual speakers identified, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Lorenzo Leggio, clinical director and deputy scientific director at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and current Chief of the Clinical Psychoneuroendocrinology and Neuropsychopharmacology Section, a joint NIDA and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) laboratory at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Intramural Research Program, provided information on the numbers of “deaths of despair” in the United States from 1900 to 2017. These are deaths due to suicide, drugs, alcohol, and alcohol-related diseases such as liver disease. “Every 4.5 minutes, someone is dying in the United States because of addiction,” Leggio said.

Unfortunately, he said, there is still a misconception that alcohol and substance use disorder are no more than “bad behaviors” or a personal choice, but there are clear scientific data showing that addiction is a brain disease (Heilig et al., 2021; Leshner, 1997; Volkow et al., 2016). Furthermore, he added, there are treatments that can help patients. There are effective behavioral treatments, and there are also medications approved by the FDA for treating opioid, tobacco, and alcohol use disorders, although still more medications are needed, he added.

The search for new medications has been aided by the recognition that the interplay and the connections between the brain and the body, including the heart–brain axis and the gut–brain axis are very important in addiction. Glucagon-like peptide-1, or GLP-1, is a key element in the gut–brain axis, he said, and the question has been raised whether the GLP-1 system might be a new target for treating addictions. There have been a number of anecdotal reports of people on GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonists experiencing reduced cravings for alcohol, tobacco, and drugs (Doucleff, 2023; Tirrell, 2023), Leggio said, “and as a physician, I really think it’s very important to listen to these people.”

Scientists have been working to understand the role of the GLP-1 system in addiction, he said, and there is already a robust literature on the

topic (for recent review, see Bruns et al., 2024). In this session, he continued, the speakers would discuss where the field stands in terms of scientific evidence on the use of GLP-1R agonists and related drugs in the treatment of addiction.

PRECLINICAL STUDIES EXAMINING THE EFFECTS OF GLP-1R AGONISTS ON ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION

Elisabet Jerlhag, a professor of pharmacology at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, provided an overview of preclinical studies—primarily laboratory studies in rats—of the effects of GLP-1R agonists on alcohol consumption. As background, she noted that alcohol use disorder cannot be modeled in animals with a single model, so researchers use different models to reflect the different aspects of the disorder.

One common model is the intermittent access model, in which rats are given both water and alcohol to drink on every second day and have access only to water on the days in between. What happens in these situations in that the rats will quickly come to drink significant amounts of alcohol on the days that it is available, to the point that their blood alcohol levels correspond with intoxication in humans.

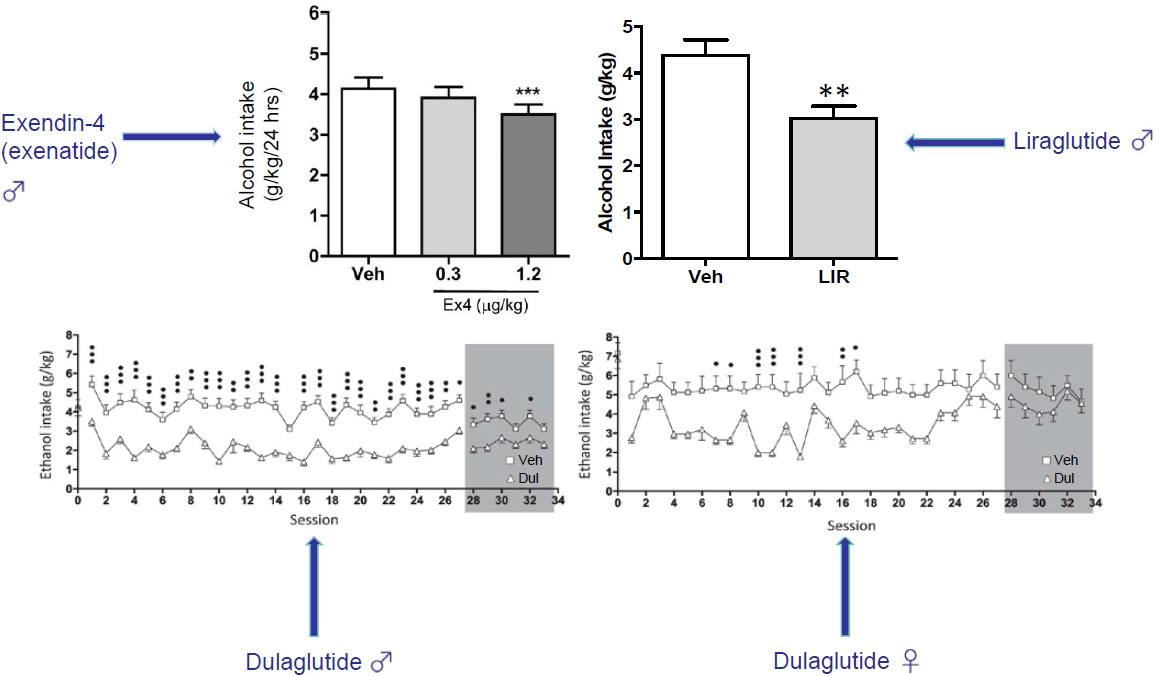

Jerlhag’s group used this model to test the effect of various GLP-1R agonists on alcohol intake in rats (see Figure 5-1). An early study showed that exendin-4 reduced alcohol intake in a dose-dependent manner (Egecioglu et al., 2013), but in retrospect the effect was quite small, she said. Later studies found much larger reductions in alcohol intake with liraglutide (Vallöf et al., 2016) and with dulaglutide (Vallöf et al., 2020). The earlier studies were done in male rats, Jerlhag said, but when her group added female rats to their investigations, they found a similar decrease in alcohol intake (Vallöf et al., 2020). Also, she added, there were no indications that the rats were building a tolerance to the GLP-1R agonists, and in some cases—the males but not the females—the treatment effect persisted after the rats were no longer receiving the drugs. Yet another experiment found that semaglutide reduced alcohol intake in both male and female rats in a dose-dependent manner (Aranäs et al., 2023). A group at NIDA reported similar findings on semaglutide and alcohol intake that same year (Chuong et al., 2023).

To see where the GLP-1R agonists were acting in the brain, Jerlhag’s group used fluorescently marked semaglutide, which they found in the nucleus accumbens in rats that were given alcohol but not in control animals (Aranäs et al., 2023). Thus, the possibility should be considered that alcohol drinking changes the penetration of the drug into the brain, she said.

A second model that the group used for alcohol use disorder was relapse drinking. In this model, the rats consume alcohol for about 3 months, it is

SOURCE: Presented by Elisabet Jerlhag on September 10, 2024. Adapted from Egecioglu et al., 2013; Vallöf et al., 2016, 2019.

taken away for 2 weeks, and then it is introduced again. In this situation the rats drink even more alcohol than they did before, which has been suggested as being parallel with alcohol craving in humans. Semaglutide was shown to prevent this relapse drinking in the rats (Aranäs et al., 2023). This is also observed by both exendin-4 and liraglutide, said Jerlhag.

A third model looked at the motivation to consume alcohol. In this case, rats are trained to press a lever to obtain alcohol, and their motivation is judged both by the total number of lever presses in a given period of time, such as 1 hour, and also by the “break point,” which is the maximum number of times a rat will press the lever to get a single alcohol reward. By these measures, both exendin-4 and liraglutide reduced rats’ motivation to consume alcohol (Egecioglu et al., 2013; Vallöf et al., 2016). In the case of liraglutide, that decrease in motivation persisted even after the rats stopped receiving the drug (Vallöf et al., 2016).

Jerlhag said that she believes the effects of these GLP-1R agonists on alcohol consumption have to do with the rewarding properties of alcohol. In both rats and humans, the desire to drink alcohol is driven to some extent by the rewards the brain associates with that drinking, and, indeed, in humans it has been shown that individuals who experience a great deal of reward from drinking alcohol are at a higher risk for alcohol use disorder later in life (King et al., 2021). In humans, the rewarding experience has been correlated to an increase in dopamine in the ventral striatum (Boileau et al., 2003), and this can also be seen in rodents. “So,” Jerlhag said, “we can model something in animals that also is seen in humans. And we hypothesize that that reflects reward in rodents as it does in humans.”

In experiments to test this, Jerlhag’s team has found that while alcohol leads to a dopamine increase in rats’ brains, treatment with exendin-4, liraglutide, or semaglutide blocks the effect (Aranäs et al., 2023; Egecioglu et al., 2013; Vallöf et al., 2016). So, they hypothesize that GLP-1 receptor agonists prevent a rat from feeling the usual reward it would get from alcohol, which contributes to a reduced alcohol intake, reduced motivation to drink alcohol, and prevention of relapse drinking.

These effects all take place in the brain. “Studies have shown that the brain GLP-1 receptors are quite important to regulate alcohol intake, but not the body GLP-1 receptors,” Jerlhag said. And there are a number of specific brain areas that seem to be involved, including the nucleus accumbens, some parts of the ventral tegmental area (VTA), the nucleus of the solitary tract (NST), and the laterodorsal tegmental nucleus (LDTg), which is interconnected with the VTA.

Relatedly, Jerlhag mentioned that nicotine use has also been studied in lab animals, with GLP-1R agonists found to prevent nicotine-related behaviors. As with alcohol, dopamine release is prevented, and the

motivation to consume nicotine is affected. Both exentin-4 and liraglutide have been shown to have these effects.

In closing, Jerlhag pointed to several next steps. She suggested, for instance, that future studies explore why different GLP-1R agonists have different outcomes. It would be useful to explore the mechanisms of action for these agonists in greater detail, and it would be valuable to study the reasons for the sex differences that are sometimes seen in response to the agonists.

DPP-4 INHIBITORS AND ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION IN RATS

Mehdi Farokhnia, a physician-scientist at NIH’s intramural research program at NIDA and NIAAA, expanded on the preclinical work studying the effects of GLP-1R agonists on alcohol consumption by describing similar studies on the effects of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors on alcohol consumption in mice and rats. DPP-4 inhibitors, which are used to treat diabetes, act in the body by increasing the levels of GLP-1, which in turn inhibits glucagon production, increasing the secretion of insulin and decreasing the level of blood glucose. Since DPP-4 inhibitors increase GLP-1 levels, they are a natural candidate for treating alcohol or drug addiction.

Offering some background on DPP-4 inhibitors, Farokhnia said that GLP-1 has a very short half-life in the body because it is degraded by DPP-4. Thus DPP-4 inhibition is an alternative approach to GLP-1R agonists for stimulating the GLP-1 system by increasing the amount of GLP-1 circulated in the body.

Farokhnia’s group initially tested the effects of two GLP-1R agonists, liraglutide and semaglutide, in male rats, and both reduced alcohol intake. Then, focusing more on semaglutide, they tested both male and female mice and rats across different paradigms, including binge-like drinking and dependence-associated drinking, and found that semaglutide reduced alcohol intake with no sex differences between males and females (Chuong et al., 2023).

To date, he noted, there has been only one clinical trial of a GLP-1R agonist in the treatment of alcohol use disorder. This was a 26-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of extended release exenatide (Klausen et al., 2022). There was no difference in the primary outcome—percentage of heavy drinking days—between the exenatide group and the placebo group. However, in a post hoc analysis, the researchers found that exenatide demonstrated a significant effect in reducing alcohol intake in those patients who had a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30. In further analyses using functional magnetic resonance imaging, they found that exenatide reduced cue reactivity (how the patients’ brains responded when showed cues that would trigger thoughts about drinking), while positron

emission tomography (PET) data showed that exenatide reduced dopamine transfer availability.

Given the preclinical work that GLP-1R agonists can reduce alcohol intake in rodents and the clinical work showing that they may have a similar effect in people, at least those with a high BMI, Farokhnia’s team examined the possibility that DPP-4 inhibitors might also reduce alcohol intake. They have tested linagliptin, which does not cross the blood–brain barrier, and omarigliptin, which does. They used different paradigms, including drinking in the dark in mice, which is a model of binge-like drinking, and also a dependence-associated model of alcohol intake in rats. So far, though, they have seen no indication that DPP-4 inhibitors might reduce alcohol intake.

To examine the potential effectiveness of GLP-1R agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors in treating alcohol use disorders from a different angle, Farokhnia’s group worked with electronic health records data from the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Veterans Aging Cohort Study. In particular, they examined people who had been treated with GLP-1R agonists or DPP-4 inhibitors and compared them to those who had not been treated with either. To estimate how much the individuals in the study drank, the researchers relied on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption (AUDIT-C), which asks three questions on alcohol drinking. The researchers only included people with an AUDIT-C score greater than 0, indicating some level of drinking at baseline, and used various statistical techniques to try to make sure that each pair of groups being compared matched up well on all the variables beyond the treatment condition. One of the strengths of this unpublished study was its size, with well over 10,000 people included in each of the groups used in the comparisons.

Additionally, the researchers examined how the two groups differed in their change in alcohol use from the beginning of treatment to the end. They found that those who had been treated with GLP-1R agonists showed a greater reduction in drinking than those in the control group or the DPP-4 inhibitor recipients. When restricted to those with a diagnosis of alcohol use disorder or those who had an AUDIT-C score of at least 8 (indicating hazardous drinking), the difference was dramatically greater—those who were treated with GLP-1R agonists had a much greater decrease in AUDIT-C scores from baseline to follow-up, said Farokhnia.

Again, however, the DPP-4 inhibitors showed no effect on alcohol use, either in the comparison between DPP-4 inhibitor users and a control or in the comparison between DPP-4 inhibitor users and GLP-1R agonist users in the unpublished study. “I always say this is the only time I was very happy to see negative results,” Farokhnia said, “because it replicates our preclinical findings.” In short, he concluded, “both preclinically and clinically we see that GLP-1R agonists reduce alcohol intake, and DPP-4 inhibitors don’t.”

He closed by saying that his team is carrying out a clinical trial of semaglutide in people with alcohol use disorder whose results should be available in a few years, and a number of similar clinical trials are being conducted in the United States and Europe. The idea that GLP-1R agonists could be an effective treatment against alcohol use disorder has been getting a great deal of attention in the media (Doucleff, 2023; Johnson, 2024; Leslie, 2023; Resnick, 2024; Tirrell, 2023), but as he and a group of colleagues in the field argued in a commentary published a few months before the workshop (Leggio et al., 2023), it will be too early to make judgments about the efficacy of these drugs until the data from clinical trials begin to appear.

PRECLINICAL STUDIES ON THE USE OF GLP-1R AGONISTS TO DECREASE COCAINE USE

Heath D. Schmidt, director of the Laboratory of Neuropsychopharmacology at the University of Pennsylvania, spoke about experiments done with GLP-1R agonists in preclinical models of cocaine use disorder. One of his lab’s goals is to identify novel anti-addiction therapies, and some of the agonists appear promising for that purpose.

The work in his lab uses the drug self-administration/reinstatement paradigm. Rats are implanted with jugular catheters, and after they have recovered from the surgery they are put into operant chambers where they can press a lever to get an intravenous infusion of cocaine. Typically, they allow the rats to self-administer cocaine for 21 days, at which point the cocaine solution is replaced with a saline solution for 5–7 days. During this abstinence period, the rats reduce their lever pressing. At this point the researchers can reinstate a rat’s drug seeking—that is, get the rat to press the lever more often—by re-exposing the animal to the same stimuli that cause cocaine-addicted humans to relapse, such as giving it an acute injection of cocaine (Hernandez et al., 2018).

To test whether a GLP-1R agonist would decrease the rats’ cocaine-seeking behavior, Schmidt’s group pretreated rats with exendin-4 before they reintroduced the cocaine solution after 1 week of abstinence. While the control rats that had not been pretreated with exendin-4 pressed the lever repeatedly seeking the cocaine, the rats given exendin-4 pressed it much less often, and the rats given the highest dose of exendin-4 pressed the lever less than one-third as often as the control rats.

The group was excited about the findings, he said, because “as far as we knew, it was the first demonstration that a GLP-1 receptor agonist could reduce drug seeking in a reinstatement model.” But they also wanted to determine whether the effect was due, at least in part, to activating GLP-1 receptors in the brain.

To see if the exendin-4 peptide penetrated the brain, the team put a fluorescent tag on the exendin-4 peptides and used that fluorescent tag to track the drug’s distribution throughout the brain. They found that exendin-4 did cross the blood–brain barrier and that it ended up in nuclei that were known to regulate drug seeking, including the VTA, the nucleus accumbens, and the laterodorsal tegmental nucleus (Hernandez and Schmidt, 2019; Hernandez et al., 2018, 2021). Another study in Schmidt’s lab, whose data have not yet been published, found that the exendin-4 induced c-Fos expression in the VTA, suggesting that it was activating neurons in the brain.

In another unpublished study, Schmidt’s lab looked to see which cells in the midbrain were expressing GLP-1 receptors. They found that GLP-1R transcripts were primarily expressed in Gad1-positive neurons in the VTA. When they looked at dopamine neurons in the VTA, they found no expression of GLP-1 transcripts. “These findings indicate that GLP-1 receptors are primarily expressed in GABA neurons in the VTA,” he said. The findings were confirmed by a second unpublished study that used single-nucleus RNA sequencing to look for GLP-1 receptor transcript expression in all cell types of the VTA.

These findings, Schmidt said, “support the hypothesis that the suppressive effects of exendin-4 in cocaine seeking may be due in part to activating inhibitory midbrain GABA neurons.”

To examine what is going on at the cellular level in more detail, Schmidt’s lab recently ran an in vivo fiber photometry experiment that allowed them to record intracellular calcium dynamics—specifically in GABA neurons of the VTA—during cocaine reinstatement tests. As before, the exendin-4 significantly reduced how often the rats pressed the lever during reinstatement tests, and they also found an increase in the activity of GABA neurons in only the exendin-4-treated rats when they were drug seeking. In a second experiment with similar technique, they looked at intracellular calcium dynamics in the dopamine neurons of the VTA rather than the GABA neurons. The control rats demonstrated a significant increase in dopamine cell activity associated with lever pressing, but this neuronal activity was not present in the rats pretreated with exendin-4.

These data point to the group’s current working hypothesis about how exendin-4 reduces cocaine-seeking behavior in rats, Schmidt said. The GABA neurons act to inhibit the dopamine neurons. When the control rats are re-exposed to cocaine after the week of abstinence, they push the lever at a high rate—that is, they are more persistent in seeking the cocaine, and there is an increase in dopamine cell activity, while the inhibitory GABA neurons are relatively quiet. However, treatment with exendin-4 activates the rats’ midbrain inhibitory GABA neurons, which in turn leads to decreased phasic dopamine cell firing and reduced drug seeking.

In summary, Schmidt said that systemic administration of a GLP-1R agonist, specifically exendin-4, attenuates drug seeking. The effective doses are well tolerated in cocaine-dependent rats; that is, they do not affect food intake, and they do not produce malaise-like effects. These preclinical findings support using GLP-1R agonists for treating cocaine use disorder. The data also suggest that the mechanism by which exendin-4 suppresses the drug-seeking behavior involves activating inhibitory GABA neurons.

Schmidt closed with a list of unanswered questions and future directions. A key research direction, he said, should be to determine the downstream molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the efficacy of GLP-1R agonists on drug-seeking and drug-taking behaviors. Part of the research should involve disentangling the relative contributions of postsynaptic versus presynaptic receptors in the behavioral responses to these agonists. He also suggested that researchers explore whether they can target central GLP-1-producing circuits in the brain to selectively reduce drug-mediated behaviors, study which GLP-1R agonists are most effective in reducing drug- and alcohol-seeking behaviors and look for any adverse effects of GLP-1R agonists in humans with substance use disorders. As an example, Schmidt said, he is particularly concerned about the potential for adverse gastrointestinal effects in humans with opioid use disorder. Finally, he concluded, he would like research to address the question of whether approaches targeting GLP-1 and additional neuropeptide systems with overlapping functional activity would be more effective and better tolerated than treatments with a single GLP-1R agonist alone.

CLINICAL TRIALS OF GLP-1R AGONISTS FOR TREATING OPIOID USE DISORDER

Patricia Sue Grigson said that people in the field have long thought about substance use disorders—and opioid use disorder in particular—in terms of their hijacking reward pathways, but perhaps they should instead be thought about in terms of their hijacking “need pathways.” “Why would individuals take such chances with their lives, with the lives of their offspring?” Grigson asked. Is it because they are seeking a reward or because they are desperately seeking to satisfy a need?

If addiction is hijacking substrates involved in these “need pathways,” she asked, could opioid seeking and taking be reduced by treatment with a known satiety agent? She and her team decided to test that possibility, by first testing GLP-1.

In one preclinical study, they let rats self-administer heroin or saline for 6 hours a day for 11 days, followed by 13 days of abstinence in their home cages. After this, the rats were injected with one dose of liraglutide at 0.3 milligrams per kilogram or with saline solution. Six hours later, they were

placed back into the test chamber with no drug available and tested for heroin seeking. The team began by inducing seeking by exposing the rats to various drug-related cues. Next, after the rats’ seeking slowed because they were not receiving any heroin, the rats were injected with a single IV infusion of heroin to trigger drug-induced seeking. Finally, the rats were injected with the stressor yohimbine to elicit stress-induced seeking.

In the case of seeking triggered by drug-related cues, Grigson’s team found that the rats with a history of heroin self-administration and that were pretreated with saline did a lot of seeking in response to these cues, but the rats that had been treated with liraglutide demonstrated significantly reduced seeking behavior. Similarly, the infusion of heroin triggered the saline-treated rats to contact the empty spout in an attempt to get more, while the liraglutide-treated subjects did not exhibit this behavior. Finally, when the animals were injected with yohimbine, the saline-treated animals exhibited seeking behavior, while those treated with liraglutide did not (Douton et al., 2022). In short, the GLP-1R agonist blocked all three “roads to relapse”—those elicited by cues, the heroin itself, and stress.

Grigson’s team saw similar results for fentanyl. Male rats that had self-administered fentanyl and then were abstinent could resist relapse if they had been treated with liraglutide (Urbanik et al., 2022), and this has been shown to be true in female rats as well (Urbanik et al., 2025). Another study showed that liraglutide administered chronically across the abstinence period instead of in a single acute dose just before the test still worked to reduce heroin seeking, particularly in rats that had a history of high drug taking (Evans et al., 2022). This is important for possible human application, as the drug regimen in this experiment more closely resembles the treatment that individuals with an opioid use disorder would undergo.

Grigson has also worked with a clinical team to examine GLP-1R agonists for the treatment of opioid use disorder in human participants in a phase 2 clinical trial.1 These participants went through medically assisted withdrawal, and they had the choice of having medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) with buprenorphine/naloxone or not. The patients were then randomized to receive either placebo or liraglutide once a day (with the dosage increasing across 18 days), then they were taken off the treatment for 2 days, and 30 days later they were followed up with a phone call.

During the course of the treatment, Grigson’s team measured blood glucose, body weight, and ambient drug craving using ecological momentary assessment, a smartphone app that asks questions four times a day about cravings, nausea, mood, and sleep. The researchers also measured blood

___________________

1 For more information on the phase 2 clinical trial, please see https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04199728?term=NCT04199728 (accessed December 30, 2024).

pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood oxygen saturation at the start of the study, with every increase in dose, and at the end of the study.

Grigson’s team recruited 25 individuals who were randomized into treatment groups. Twenty of them were tested with the ecological momentary assessment. Thirteen chose to have the buprenorphine/naltrexone MOUD, of which six were given placebo and seven received the liraglutide; of the seven who did not choose MOUD, four received a placebo and three got liraglutide. The liraglutide proved to be safe. It did not adversely affect body weight, blood glucose, or cardiovascular function in the 3-week study.

To measure efficacy, Grigson’s group collected 596 data points across 202 days. They used the Desire for Drug Scale, which asks responders to rate three aspects of desire for drugs on a five-point Likert scale—whether drugs intruded on their thoughts that day, whether they have missed the feeling that drugs can give them, and whether they have thought about how satisfying drugs can be (Love et al., 1998). The score on the scale is the average of the responses to the three items, which range from 0 for strongly disagree to 4 for strongly agree. The scale, originally developed for alcohol use disorder, has been shown to be a valid measure for opioid use disorder as well (Cleveland et al., 2021).

The team’s analysis of the data showed that individuals who were treated with liraglutide reported 40 percent less opioid craving than those that were treated with placebo, Grigson said. Importantly, she added, they found that the GLP-1 agonist was significantly effective beginning with the lowest dose. The individuals on placebo experienced increased craving as the day wore on from morning through evening, while the craving remained relatively flat throughout the day for those in the liraglutide group, so that they reported having significantly less craving than the placebo group in the afternoon and evening. Both groups reported high levels of stress, but for the individuals on the placebo, their higher levels of stress were associated with higher levels of craving, which was not the case for those taking the liraglutide.

The clinical trial did have some limitations, Grigson said, such as its sample size, the fact that the population was mostly male and mostly White, and that it was done in a residential setting. However, it did clearly indicate that the GLP-1R agonist was effective in reducing opioid craving, beginning with the lowest dose. It was effective at times of high risk, specifically the afternoon and evening, it was effective with or without the MOUD, and it dissociated craving from stress.

Looking to the future, Grigson concluded, more research is needed to understand the optimal treatment, such as how to identify the ideal drug, dose, treatment regimen, drug combinations, treatment parameters, and concomitant treatments to address psychological and physiological issues.

USING REAL-WORLD EVIDENCE TO STUDY THE USE OF SEMAGLUTIDE IN TREATING SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS

Carrying out randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to test the effectiveness of GLP-1R agonists in treating substance use disorders is very expensive and time-consuming, noted Rong Xu, a professor of biomedical informatics and founding director of the Center for Artificial Intelligence in Drug Discovery at Case Western Reserve University. She and her team have instead taken advantage of the large amounts of real-world data available in a large health care database to emulate RCTs and generate information about the effectiveness of these drugs much more quickly and less expensively than can be done with actual RCTs.

Xu’s team uses longitudinal data from TriNetX, a Boston-based company with access to data on 250 million unique patients from 120 health organizations across 19 countries. Xu’s studies have focused on U.S. data, which covers 117 million patients from 66 health care organizations across all 50 states. The data are very rich, including demographics, social determinants of health, genomic data, test diagnoses, and medication procedures, with up to 20 years of patient history. The health records are de-identified, so the patients are anonymous.

A randomized clinical trial generally has seven components, Xu said: eligibility criteria, treatment strategies, treatment assignment, outcomes, follow-ups, causal contrast of interest, and statistical analysis. In emulating such a trial with real-world data, she continued, the biggest challenge is the treatment assignment. “For randomized clinical trials, you randomly assign the treatment strategy to a participant,” she said, but this isn’t possible for real-world data. Instead, her team uses propensity score matching to make sure the exposure cohort and the comparison cohort are similar in terms of their characteristics. The resulting emulation trial generally costs less than $1 million to perform on potentially millions of patients, while a randomized trial with hundreds of patients will typically cost $10 million to $50 million, Xu said.

The first study her team published using this approach looked at the GLP-1R agonist semaglutide and its effects on alcohol use disorder (Wang et al., 2024a). In that study they looked at four cohorts that each had 5,000–80,000 participants: patients with obesity and no prior alcohol use disorder (AUD), patients with type 2 diabetes and no prior AUD, patients with obesity and preexisting AUD, and patients with type 2 diabetes and preexisting AUD. In the two obesity cohorts, they compared patients given semaglutide versus patients given other types of weight loss drugs, while in the two diabetes cohorts they compared patients given semaglutide versus patients given other anti-diabetes drugs. In the two cohorts whose members had no existing AUD, the outcome of interest was a first-time diagnosis of

AUD, while in the two cohorts whose members had preexisting AUD, the outcome of interest was a subsequent medical encounter for AUD. The patients were followed for 12 months, and the time at which an outcome of interest occurred, if it did, was recorded.

After analyzing the data, Xu’s group found that semaglutide was associated with a decreased risk for developing AUD by 50 percent among those who had never had the disorder and a risk for recurrent AUD decreased by 56 percent among those who had previously been diagnosed with AUD. For type 2 diabetes, the corresponding decreases were 44 percent and 40 percent (Wang et al., 2024a). It is possible, Xu said, that the decreases were lower in the case of diabetes because semaglutide was generally prescribed at a higher dosage for obesity than for diabetes.

Xu’s group used the same study approach—four cohorts covering both obesity and diabetes and both individuals with a preexisting cannabis use disorder (CUD) and those with no history of the disorder—to look at the effects of semaglutide on CUD (Wang et al., 2024b). The results were similar: Among patients with obesity there was a 44 percent reduction in the number of cases of incident CUD and a 38 percent reduction in recurrent CUD. Among those with type 2 diabetes there was a 60 percent reduction in incident CUD and a 34 percent reduction in recurrent CUD.

In a third study they examined the effect of semaglutide on tobacco use disorder (TUD). In this case, they looked at more than 200,000 patients with type 2 diabetes and preexisting TUD. They did not look at patients with obesity because the relationship between smoking and losing weight would introduce too many confounding factors. Patients on semaglutide were compared with patients on each of seven other anti-diabetes drugs, including first-generation GLP-1R agonists. They found that semaglutide was consistently associated with a reduction of 12–30 percent in diagnoses of TUD in all the stratified populations, a 40–70 percent reduction in the prescription of smoking cessation medication prescription, and a 20–30 percent reduction for smoking cessation counseling (Wang et al., 2024c).

In a fourth study they looked at patients with type 2 diabetes and a preexisting opioid use disorder and found that being treated with semaglutide was associated with about a 50 percent reduction in the risk of opioid overdose when compared with other anti-diabetes medications (Wang et al., 2024d). A fifth study found semaglutide to be associated with a 50–80 percent reduction in risk for suicidal ideation in both patients with obesity and patients with type 2 diabetes (Wang et al., 2024e).

In closing, Xu said that when her group used real-world data to emulate randomized clinical trials, they found evidence supporting potential benefits of using semaglutide for treating multiple substance use disorders. The limitations of the work include the fact that real-world data have various confounders and biases, and trial emulations do not necessarily

capture the outcomes from randomized clinical trials. Thus, in the future it will be necessary to carry out RCTs to verify the findings of these trial emulations, she said. Future work should also be aimed at understanding the mechanisms of action involved in GLP-1R agonists’ ameliorating substance use disorders.

DISCUSSION

Effects of GLP-1R Agonists on Endogenous GLP-1 Levels

Brian Fiske brought up the DPP-4 data that Farokhnia had discussed and said it reminded him of a question from an earlier session concerning whether it might not be feasible to elevate endogenous GLP-1. Could the system be so tightly regulated, he asked, that it would essentially be impossible to increase endogenous GLP-1 enough to meaningfully stimulate the GLP-1 system without directly targeting the receptors themselves? Is that what the DPP-4 data imply?

“That’s what we are thinking right now,” Farokhnia replied. Since the experiments he talked about were very preliminary, his group is carrying out more experiments, including measuring endogenous GLP-1 levels to see how much the levels are increased by the DPP-4 inhibitors. And even if a DPP-4 inhibitor did increase the levels of exogenous GLP-1 levels, he continued, it is quite possible that this increase would not help in controlling substance use disorders since although DPP-4 inhibitors regulate blood glucose levels in patients, they do not really affect appetite or eating.

In response to a question on the effects of GLP-1R agonists on the central norepinephrine system, Jerlhag said her lab has looked at that issue for various agonists, and the only one they have found so far that affects that system is liraglutide. “We found that it affected noradrenaline in prefrontal cortex, but not in any other areas,” she said.

Then, on the issue of whether GLP-1R agonists paired with GIP analogs might have a greater effect together than either has by itself, Jerlhag said her lab has done extensive studies on that, and they have found a strong positive effect from the dual agonist tirzepatide. It appears tirzepatide has a somewhat stronger effect than semaglutide, though the stronger effect is mainly visible in females.

Possible Mechanisms in the Actions of GLP-1R Agonists for Substance Use Disorder

Serena Jingchuan Guo, an assistant professor in the Department of Pharmaceutical Outcomes and Policy at the University of Florida College of Pharmacy, asked about the existence of studies looking into the mecha-

nisms behind the addiction prevention effects of GLP-1R agonists. As background, she described a targeted trial emulation study that her group had carried out with a national sample of Medicare beneficiaries. In the patients with a preexisting opioid use disorder, the researchers found that GLP-1R agonists had a modest protective effect against the opioid overdose, but in patients with no history of opioid use disorder or opioid overdose history, they found that, compared with DPP-4, the GLP-1R agonist was associated with an increased risk of newly diagnosed opioid use disorder. “We haven’t submitted it for publication yet,” she said, “because we couldn’t find a mechanism study to support the biological possibility.”

Xu said that in an unpublished study of semaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes, when they used AI to identify the targets of semaglutide in substance use disorder, they found that semaglutide has a lot of off-target effects beyond GLP-1 receptors. Indeed, she said, the top effect was not with a GLP-1 receptor but instead was something related to a brain reward system.

Regarding the effects Guo saw, Grigson suggested that “one might wonder if the drug is experienced as less reinforcing for the new users, and they might have been compensating by trying a higher dose.”

In response to a question about whether some of the effects of the GLP1R agonists on substance use might be due to aversion in the same way that reduced food intake for some of these drugs is related to nausea in humans, Jerlhag said her team used very low doses in their studies, and tests showed that these doses did not appear to affect nausea at all. Furthermore, the various GLP-1R agonists are consistent in their reduction in the rewarding effects of alcohol, especially by dopamine release.

Schmidt expanded on that answer. “I don’t think that the cocaine-exposed brain necessarily reacts the same way to these drugs that a drug-naive brain would,” he said, which is supported by preclinical studies. In their cocaine studies, for example, they have identified both systemic and intracranial doses of GLP-1R agonists that selectively reduce cocaine seeking and don’t affect food intake or produce malaise-like effects. “I think we’re taking a very dopamine-centric view of the mechanisms here,” he continued, “but there are certainly other circuits that are going to be involved.” In particular, one nicotine study showed that activating GLP-1 receptors in the medial habenula–interpeduncular nucleus pathway increases the aversive effects of nicotine (Tuesta et al., 2017). So there are clearly other things than just dopamine involved in both the reward and aversion circuits in the brain, Schmidt said.

Grigson added that in an unpublished preclinical study she found that the GLP-1R agonist reduced evidence of naloxone-induced withdrawal (i.e., aversive faces to a taste cue that has been paired with naloxone-induced withdrawal). It is possible, she said, that the agonist’s effects involve not

just reducing the rewarding aspects of a drug but also the aversiveness of the craving for the drug. “We’ll need more work to demonstrate that, though,” she said.

Matthew Hayes asked about the role of stress in addiction and relapse, and Farokhnia said that there is a long line of literature showing that different types of stress and stress neuropeptides do trigger relapse and drug-seeking behavior. However, Farokhnia continued, “like the link with GLP-1, I don’t think there has been a lot of work in the substance use arena. As everyone said, it’s been very dopamine-centric so far.”

A workshop participant asked whether substance use might affect the blood–brain barrier and alter the access of a GLP-1R agonist to the brain. Leggio noted that, similar to patients with Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s disease, there is some evidence that the blood–brain barrier is disrupted in people with substance use disorder. Jerlhag added that in her tests on alcohol-drinking rats, fluorescently marked semaglutide was binding into the nucleus accumbens, which had not been shown in regular rats. That is an indication, she said, that semaglutide might pass more deeply into the brain, at least in rodents.

Other Possible Factors Involved in GLP-1R Efficacy

Alexandra Sinclair pointed to the studies that found the GLP-1R agonists to be effective against alcohol use disorder only in a subgroup that had obesity, and she also noted that epidemiological studies of the efficacy of GLP-1R agonists against substance use disorder tended to have data mainly from patients with obesity because they were the most likely to be prescribed one of the agonists. Given that, she said, what is known about possible differences in efficacy between individuals with and without obesity? To Farokhnia’s understanding, the only clinical trial testing GLP-1R agonists on alcohol use disorder is the one he described in his presentation. That trial did find that people with a high BMI had a better response, but since it is the only such trial so far, it is too soon to know for sure whether that relationship between BMI and response will hold up. In their ongoing clinical trial, they are recruiting a wider range of participants, he said, but safety considerations keep them from recruiting people with a BMI below 25 because of concerns they might get too thin. Still, he concluded, “it’s very plausible to think that people with higher BMI may respond better to these medications.”

Leggio wrapped up the discussion session by responding to an online question from a workshop participant who asked about the social effects that GLP-1R agonists might have in humans. “Addiction is a complex disease where there are many social determinants,” Leggio said. He added that one of the main challenges relative to these drugs, in addition to determin-

ing whether they work in people with addiction, will be implementing them at the community level. “Today we do have medications approved by the FDA to treat addiction, but they’re only used for 2 percent to 20 percent of the patients,” he said. “So, think about if this was a cancer workshop, and I was telling [you] today that we only treat 2 percent to 20 percent of people with cancer. That would be unacceptable.” Given that, Leggio said, people in the field should also be thinking about implementation and the social implications for their patients.