Impact of Burnout on the STEMM Workforce: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: Appendix D: Breaking the Burnout Cycle: Building Organizational Strategies to Address Burnout Sources and Symptoms

Appendix D

Breaking the Burnout Cycle: Building Organizational Strategies to Address Burnout Sources and Symptoms

Arla Day

This paper was commissioned by National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Committee on Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine. Opinions and statements included in the paper are solely those of the individual authors, and are not necessarily adopted, endorsed, or verified as accurate by the committee or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

ABSTRACT

From its “inception” in the 1970s, we have accumulated decades of research outlining the antecedents and outcomes of burnout. The definition of burnout has remained comparatively stable, such that there is a degree of consensus on what burnout is (i.e., a syndrome of feeling emotionally exhausted, feeling detached/cynical toward others, and having a low sense of professional efficacy) (Maslach, 1976). An integral premise of job burnout is that its root causes are due to work-related factors, rather than individual “characteristics.” Therefore, when trying to ameliorate job burnout, efforts targeting the job (e.g., job redesign), the leader (e.g., effective leadership training), and the overall organization may be the most effective. Despite the abundance of burnout research, there is a relative paucity of actual intervention studies and best practices for individuals and organizations aimed at reducing the sources of burnout. Ironically, most interventions aim to

manage symptoms of burnout rather than eliminate the sources of burnout, such that they target individual workers—despite acknowledging the organization as the source of the burnout, creating a burnout intervention dilemma. The goal of this paper is to review burnout inventions, create a conceptual framework identifying the sources and intervention points for burnout, understand why there is symptom treatment vs. source discrepancy, identify gaps and discrepancies in the current literature, and provide suggestions for novel practices in addressing burnout.

INTRODUCTION

The early works of Freudenberger (1974, 1975) and Maslach (1976), which identified a pattern of worker exhaustion, cynicism/depersonalization of others, and feelings of a lack of accomplishment and professional efficacy, commenced a long and in-depth research and practice journey on burnout. There has been much written about burnout’s prevalence (Papazian et al., 2023; Woo et al., 2020), antecedents, and outcomes (Maslach et al., 2001). In stark contrast to this long history and the close to 2 million articles, books, and chapters written on it (Google Scholar, accessed August 17, 2024), our understanding of how we can best address burnout and reduce the sources of burnout is strikingly minimal. That is, by and large, we are lacking substantial knowledge in this area. Nevertheless, there are excellent studies demonstrating the utility of specific interventions, and there has been a recent growth of these intervention studies, as well as in meta-analyses on burnout interventions. These works highlight the areas of consistency in our knowledge, as well as the gaps, and the questions about quality of designs to improve our knowledge. Therefore, this paper incorporates the key literature, focusing on meta-analyses of work-related burnout interventions, identifying types of interventions, their overall efficacy, along with paths forward for research and practice.

More specifically, the purpose of this paper is threefold:

- To outline current knowledge as well as gaps in knowledge about burnout intervention research, with a focus on the sources of burnout (as a mechanism to look at interventions and required components of intervention programs)

- To provide a conceptual framework/overview of burnout, integrating the levels of burnout interventions to reduce the sources of burnout (i.e., primary interventions) and address burnout

- responses/symptoms by supporting employees who may develop burnout (i.e., secondary interventions) or who currently are burnt out (i.e., tertiary interventions)

- To understand rationales behind the lack of organizational practices, identify best practices and novel ways to address burnout, and create tips for organizations

WHAT IS BURNOUT: CONCEPTUALIZATION, DEFINITION, AND MEASUREMENT

Although some slight definitional variations exist, in general burnout is conceptualized as a response to prolonged exposure to workplace stressors (Freudenberger, 1974; Maslach, 1976; Maslach and Leiter, 2021). The World Health Organization (2022, p. 1748) classifies burnout as an occupational phenomenon and syndrome resulting from “chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed,” stipulating that it “refers specifically to phenomena in the occupational context and should not be applied to describe experiences in other areas of life.”

The most widely accepted definition of burnout classifies it as an ongoing syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion (EE); depersonalization (DP) or cynicism (CYN); and a lack of personal accomplishment (PA) or professional efficacy (PE) (see Maslach, 1976; Maslach et al., 1997; Maslach et al., 2001).1 EE involves feelings of physical and psychological fatigue, a loss of energy to complete tasks, and being unable to replenish one’s energy levels. DP/CYN involves negative, cynical, detached feelings and behaviors toward others at work, with a corresponding dismissal of them. Finally, reduced PA/PE involves a diminished feeling of accomplishment, professional competence, and self-efficacy, such that they do not feel like they are contributing or making a “real” difference in their work. Overwhelmingly, the primary measure of this concept of burnout is the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; Maslach et al., 1997), often being called the burnout “gold standard” (Thomas Craig et al., 2021).

However, despite the popularity of the MBI and its three-phase conceptualization, researchers have created alternative, but similar, scales. In general, these measures either use a similar framework as the MBI (e.g., Salmela-Aro et al., 2011), or a more simplified framework, focusing solely on exhaustion-like constructs and outcomes. For example, the Oldenburg

___________________

1 See Chen et al. (2012) for other definitions of burnout.

Burnout Inventory, or OLBI, measures two factors of exhaustion and disengagement (Demerouti et al., 2001; Demerouti et al., 2003; Halbesleben and Demerouti, 2005). The Shirom-Melamed Burnout Questionnaire measures physical fatigue and cognitive weariness (Shirom and Melamed, 2006) and tension and listlessness (Lundgren-Nilsson et al., 2012). The Bergen Burnout Inventory, or BBI, measures exhaustion, cynicism, and inadequacy (Matthiesen, 1992; Feldt et al., 2014; Salmela-Aro et al., 2011),2 and the Karolinska Exhaustion Scale measures aspects based on exhaustion: lack of recovery, cognitive exhaustion, somatic symptoms, and emotional distress. (Saboonchi et al., 2013). Finally, the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (Kristensen et al., 2005) assesses fatigue/exhaustion. Focusing solely on a fatigue/exhaustion component is deficient in examining burnout because exhaustion is a necessary, but not sufficient, criterion for burnout (Maslach et al., 2001). “Exhaustion is not something that is simply experienced—rather, it prompts actions to distance oneself emotionally and cognitively from one’s work” (Maslach et al., 2001, p. 403). Thus, studies typically use the MBI, and caution is advised when reading studies with single-item “measures” of burnout.

Organizing Framework to Study Burnout Interventions

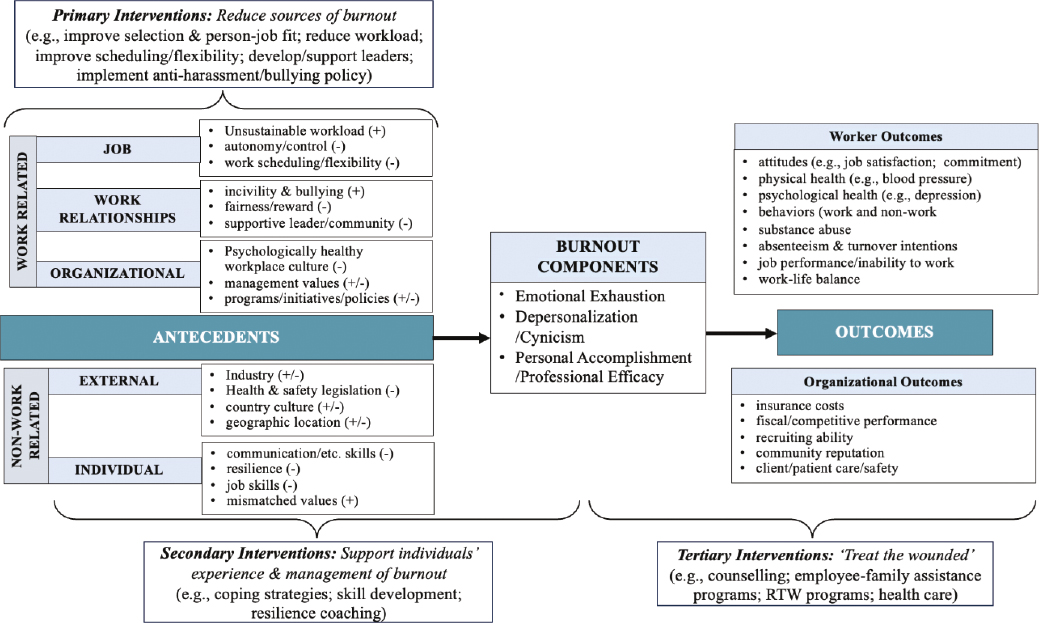

The first step in understanding how to address burnout is to examine its relationships with individual and organizational demands and resources, as well as individual and organizational outcomes. Figure D-1 is a general conceptual framework, encapsulating both burnout outcomes and sources, while categorizing these sources in a meaningful way to aid in developing burnout interventions. Figure D-1 builds on the premise that there are multiple sources of burnout, and thus, incorporating different levels of interventions (primary, secondary, and tertiary), and differentiating when and how to reduce sources of burnout versus address symptoms of burnout, is important. It also recognizes the importance of planning interventions that focus on the individual, group, leader, and organization levels (Nielsen et al., 2013), identifying these burnout sources and how they can influence the burnout response.

___________________

2 Matthiesen (1992) is the original author of the BBI, and Salmela-Aro et al. (2011) have a nine-item reduced version of the scale. Although the Matthiesen document is not publicly available, the items from the BBI are in Salmela-Aro et al.

Outcomes of Burnout

Multiple works have demonstrated the negative impact burnout can have on individual and organizational outcomes (e.g., Maslach et al., 2001; Swider and Zimmerman, 2010). As shown in Figure D-1, burnout can lead to negative psychological, physical, and behavioral outcomes for individuals. It also can lead to negative outcomes for the organization. Burnout also may have negative outcomes for families, such that burnout can affect burnout and well-being in one’s partner (e.g., Bakker, 2009; Thompson et al., 2020; Westman et al., 2001).3 For example, women’s EE (which results from job and emotional demands at work) affected their male partner’s level of EE (Demerouti et al., 2005).

Burnout can affect job attitudes (e.g., reduce job satisfaction; Iverson et al., 1998; Madigan and Kim., 2021) and affect overall life satisfaction and well-being (Demerouti et al., 2005). Burnout can increase levels of absenteeism (Iverson et al., 1998) and intentions to quit (Madigan and Kim, 2021). Burnout has been associated with increased use of psychotropic medication (Leiter et al., 2013) and negative physical health (e.g., blood pressure) and psychological health (Salvagioni et al., 2017). In their meta-analysis of burnout and safety, Salyers et al. (2017) found that higher burnout (higher EE and DP, and lower PA) was associated with reduced job performance and increased errors on the job (e.g., reduced patient safety, lower quality of healthcare). In their meta-analysis of burnout and job performance, Corbeanu et al. (2023) found that exhaustion, depersonalization, and inefficacy were associated with lower job performance. These relationships with well-being outcomes have implications for when and how we address burnout via tertiary interventions (see below).

Sources of Burnout

There also is a significant amount of research on the antecedents of burnout (see Leiter and Harvie, 1996; Maslach et al., 2001). Understanding the factors that foster/exacerbate burnout can help us to better understand how to address burnout. Leiter and Maslach (1999) identified six areas of work that contribute to burnout: workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values, and they measure these factors based on the perceived mismatch between worker and workplace. Although originally developed

___________________

3 For the purpose of this paper, individual factors and the work/organizational environment are the primary focal areas.

as antecedents of job stress, Sauter et al.’s (1990) psychosocial risk factors (e.g., workload and work pace, work schedule, roles stressors, career security, interpersonal relationships, and job content) also contribute to the development, and our understanding of, burnout. Figure 1 provides an abridged framework of these working life antecedents and psychosocial risk factors, clustering them into three work categories, and two nonwork categories: (a) job-level factors; (b) group or interpersonal factors, including leadership relationships and effectiveness; (c) organizational-level factors/culture; (d) individual-level characteristics; and (e) external factors.4 Based on Leiter and Maslach, there is also the understanding that person-job/organization misalignment of the factors within these categories can create burnout.

Job Factors

Job characteristics tend to be viewed as the key predictors of the occurrence of emotional exhaustion (Maslach et al., 2001). Workload (Iverson et al., 1998), long shifts and limited staffing (Dall’Ora et al., 2020), job control (Aronsson et al., 2017), autonomy (Iverson et al., 1998), and lack of schedule flexibility (Dall’Ora et al., 2020) are all associated with increased burnout. Leiter et al. (2013) found that specific job characteristics, such as information flow, skill discretion, decision authority, and predictability, were associated with reduced burnout over an 8-year time span. In their meta-analysis, Aronsson et al. (2017) found an association between workload and EE. Job-specific demands associated with COVID-19 also increased burnout: increased workload and a lack of specialized training regarding COVID-19 was associated with higher levels of burnout in nurses (Galanis et al., 2021). Similarly, healthcare workers who worked prolonged night shifts during the pandemic and were exposed to traumatic events experienced higher levels of burnout (Chirico et al., 2021).

Work Relationships

Negative work relationship factors (including team interactions and supervisor support) are associated with increased burnout (e.g., Iverson et al., 1998; Spector and Nixon, 2023). Conversely, overall workplace support can

___________________

4 The focus of this paper is on work factors, so while acknowledging there are multiple nonwork factors that could potentially affect burnout, nonwork factors are excluded from any in-depth reviews here.

be associated with lower EE (see Aronsson et al.’s meta-analysis, 2017). EE is associated with other mistreatment factors, such as specific supervisor and co-worker support, justice, and reward (Aronsson et al., 2017). Cynicism was associated with job demands, such as a lack of control and support, and personal accomplishment was only associated with reward (Aronsson et al., 2017). Supervisor, coworker, and peer support all tend to be associated with lower burnout (see, e.g., Iverson et al., 1998).

Leadership is an important relationship factor: In their meta-analysis, Harms et al. (2017) found that transformational leadership and leader-member exchange is associated with lower levels of EE and DP, and higher PA, whereas abusive supervision is associated with higher levels of all three components of burnout. In their logistic regression, Dyrbye et al. (2020) found that each 1-point increase in leadership score was associated with a 7 percent decrease in burnout.

The leadership-burnout relationship may be mediated by thriving, such that transformational leadership increases one’s levels of thriving, which reduces one’s levels of burnout (Hildenbrand et al., 2018). Harms et al.’s (2017) meta-analysis also highlighted an often-ignored part of the relationship: leaders’ levels of burnout can influence their own leadership behaviours. That is, leader burnout was associated with lower transformational leadership and higher levels of abusive supervision. Lower levels of transformational leadership and leader-member exchange and higher levels of abusive supervision are associated with higher levels of burnout for their followers.5 Similarly, workplace bullying is associated with increased burnout: bullying was related to a lack of satisfaction of employees’ need for autonomy, and this unmet need was associated with increased burnout (Trépanier et al., 2013).

Organizational Factors

Finally, poor organizational environments and a lack of resources are also associated with increases in burnout (Leiter et al., 2013). Organizational variables have been identified as the primary drivers to burnout (Gómez-Urquiza et al., 2020). Collectively, Kroth et al. (2019) found that general working conditions accounted for 36.2 percent of variance in burnout. In a prospective study on burnout in Finnish workers, working

___________________

5 Harms et al. (2017) caution that most of the studies in their meta-analysis used same source data. Thus, followers who had higher levels of burnout may have rated their leaders/supervisors more negatively.

conditions (measured in 1985) were associated with job burnout measured 13 years later in 1998 (Hakanen et al., 2011). There also is some limited evidence that job insecurity (which may reflect stressful or unstable work environments/cultures) is associated with EE and CYN (Aronsson et al., 2017).

Specific organizational practices, and ineffective practices, can negatively affect workers as well. For example, in their systematic review of interventions addressing health information technology stressors, Thomas Craig et al. (2021) argued that “the primary drivers of burnout for physicians have been related to electronic health records (EHRs) and overwhelming inefficiencies in clinical practice” (p. 986; see also Tutty et al., 2019), both of which can create ineffective workflows and reduced patient care. Similarly, Kroth et al. (2019) found that the usage and design of EHRs accounted for small, but significant, increases of variance in burnout. Day et al. (2017) studied workers in a healthcare organization that was going through a large reorganization: Workers’ perceptions of the organizational changes and demands they experienced during this reorganization was associated with increased EE and CYN levels, and reduced PE.

Types of work cultures can contribute to burnout: Masculinity contest culture occurs when workplaces (and organizational leaders) promote norms, practices, and values centered on competition and dominance in line with traditional masculinity ideals (Berdahl et al., 2018), and they have been associated with higher levels of burnout (Regina and Allen, 2023). Conversely, a supportive workplace culture that promote worker health and well-being are associated with lower levels of burnout. For example, after controlling for baseline levels of burnout, organizational culture that valued a focus on health was associated with reduced burnout 1 year later (Ybema et al., 2011).

External factors, such as COVID-19, also can increase organizational demands, creating more opportunities for burnout to occur, especially in healthcare workers. Not surprisingly, nurses experiencing increased demands/threats within their workplace had a higher risk of burnout: Having increased threats of COVID-19, working in high-risk environments, working long hours in quarantined spaces, and having insufficient supports (e.g., personal safety equipment, human resources support) were all risk factors for burnout (Galanis et al., 2021).

Individual Risk Factors

Although not the focus of this review, it is worth noting that individual factors can affect the level and experience of burnout. Therefore, we need to

take these factors into consideration when assessing burnout and designing and implementing burnout interventions. Simionato and Simpson (2018) found that younger psychotherapists with less work experience tended to have a higher risk for experiencing burnout. Similarly, during the pandemic, younger nurses (Galanis et al., 2021) and trainees and younger healthcare workers with less work experience (Chirico et al., 2021) also tended to be at more risk for burnout. There also is some suggestion that individual characteristics affect how one interprets, reacts to, and benefits from burnout interventions (Bartunek et al., 2006). Therefore, these factors can influence intervention effectiveness.

A MULTI-LEVEL ORGANIZATIONAL BURNOUT STRATEGY

Despite a solid appreciation of the effects of these antecedents on burnout, there has been limited progress in effectively “addressing” job burnout. Understanding these burnout sources (as shown in Figure D-1) highlights the complexity of the task: If burnout can arise from different antecedents and contexts, there probably is no simple, magic bullet to eliminate/manage burnout. Understanding burnout also highlights the substantial philosophical and practical differences in what it means to address burnout; that is, addressing burnout can either mean eliminating the sources of burnout or simply managing the symptoms of burnout.

Thus, as shown in Figure D-1, burnout can be addressed by (a) reducing the source of burnout, (b) changing one’s capabilities to handle burnout, and/or (c) reducing the symptoms of burnout (i.e., primary, secondary, and tertiary work interventions, respectively). Primary initiatives are aimed at changing the work environment (i.e., reducing the source of burnout and/or redesigning the workplace to minimize the stressors and/or increase resources to do one’s job; Hurrell and Sauter, 2013) and prevent burnout (LaMontagne et al., 2007). Primary interventions involve initiatives such as job redesign, organizational health regulations, and culture initiatives (Hurrell and Sauter, 2013), as well as workload management, increasing flexibility/autonomy to manage workload (e.g., De Simone et al., 2021); leader training (to support their team); and group training (e.g., to improve poor interpersonal relationships; e.g., Leiter et al., 2011, 2012).

Secondary programs target the individual and have the goal of providing support/training to help the employee cope with existing stressors (Maricuțoiu et al., 2016), to prevent the worsening of burnout symptoms (Bes et al., 2023), or to better cope with potential or anticipated daily or

ongoing work stressors (e.g., technology breakdowns, client rudeness). These interventions involve individual-based training and support, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), mindfulness, relaxation training, as well as work-related skills training (job training, communication skills training, etc.). Secondary programs aimed at general stress management and work-life balance (Hurrell and Sauter, 2013) also have been used to address burnout (Lloyd et al., 2013). Finally tertiary interventions address the burnout symptoms (i.e., “healing the wounded”), such that they prevent the progress of symptoms, reduce the extent of the disability, provide accommodations, and help to restore individual functioning (Hurrell and Sauter, 2013). These initiatives may include employee assistance programs, accommodations, and return-to-work programs.

REVIEW OF BURNOUT INTERVENTION META-ANALYSES

To provide an overview of the status of the burnout intervention literature, I reviewed meta-analyses that have been conducted on the different types of interventions addressing job burnout across organizations. I screened out most papers that were not true meta-analyses (e.g., systematic reviews, or “meta-analyses” with only two studies), or that did not look at the efficacy of some type of organizational or individual focused work process or intervention, or that did not have a worker sample. Table D-1 is an overview of these meta-analyses conducted on the efficacy of burnout interventions. I included meta-analyses up to 2024. I then reviewed the literature to search for additional relevant articles from the past few years that had not been included in a meta-analysis.

There was considerable variability in the types of interventions offered across the studies/meta-analyses. Compared with the vast literature on individually focused (primarily self-care) types of interventions, there are relatively few studies of organizational-based burnout interventions (Gregory et al., 2018). That is, despite a need to change the environment to reduce stressors, most interventions focus on making the individual more resilient to the ongoing work demands/stressors (Gregory et al., 2018). For example, of the 33 studies of healthcare workers in Cohen et al.’s (2023) meta-analysis, only 3 involved organizational-focused interventions (the other 30 involved individually focused interventions). Similarly, only 3 of the 39 interventions studies in de Wijn et al.’s (2022) meta-analysis, and 2 of 11 studies in the Bes et al. (2023) meta-analysis, involved organizational-based interventions.

TABLE D-1 Meta-Analysis-Based Studies of Burnout Interventions

| 1st Author Date Journal | Primary Findings | Studies & Sample Information | Overview of Intervention Types | Other Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ahola et al., 2017 Burnout Research |

|

|

|

|

|

Beames et al., 2023 Educational Psychology |

|

|

|

|

|

Bes et al., 2023 International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health |

|

|

|

|

|

Burton et al., 2017 Stress & Health |

|

|

|

|

|

Chakraborty et al., 2023 The Malaysian Journal of Nursing |

|

|

|

|

| 1st Author Date Journal | Primary Findings | Studies & Sample Information | Overview of Intervention Types | Other Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Thomas Craig et al., 2021 Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association |

|

|

|

|

|

De Simone et al., 2021 Aging Clinical and Experimental Research |

|

|

|

|

|

de Wijn et al., 2022 International Journal of Stress Management |

|

|

|

|

|

Dreison et al., 2018 Journal of Occupational Health Psychology |

|

|

|

|

| 1st Author Date Journal | Primary Findings | Studies & Sample Information | Overview of Intervention Types | Other Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Estevez-Cores, 2021 Journal of Occupational Health Psychology |

|

|

|

|

|

Fendel et al., 2021 Academic Medicine |

|

|

|

|

|

Haslam et al., 2024 American Journal of Medicine |

|

|

|

|

|

Iancu et al., 2018 Educational Psychology Review |

|

|

|

|

|

Lee & Cha, 2023 Scientific Reports |

|

|

|

| 1st Author Date Journal | Primary Findings | Studies & Sample Information | Overview of Intervention Types | Other Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lee et al., 2016 Applied Nursing Research |

|

|

|

|

|

Li et al., 2023 Behavioral Sciences |

|

|

|

|

|

Ma et al., 2023 Journal of Clinical Nursing |

|

|

|

|

|

Maricuţoiu et al., 2016 Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology |

|

|

|

|

| 1st Author Date Journal | Primary Findings | Studies & Sample Information | Overview of Intervention Types | Other Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ochentel et al., 2018 Journal of Sports Science & Medicine |

|

|

|

|

|

Oliveira et al., 2021 Educational Psychology Review |

|

|

|

|

|

Panagioti et al., 2017 JAMA Internal Medicine |

|

|

|

|

Perski et al., 2017 Scandinavian Journal of Psychology |

|

|

|

|

|

Salvado et al., 2021 Healthcare |

|

|

|

|

| 1st Author Date Journal | Primary Findings | Studies & Sample Information | Overview of Intervention Types | Other Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Soriano-Sánchez and Jimenez-Vazquez, 2023 Revista Acciones Médicas |

|

|

|

|

|

Suleiman-Martos et al., 2020 Journal of Advanced Nursing |

|

|

|

|

|

Wang et al., 2023 Frontiers in Psychiatry |

|

|

|

|

|

West et al., 2016 The Lancet |

|

|

|

|

| 1st Author Date Journal | Primary Findings | Studies & Sample Information | Overview of Intervention Types | Other Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Yildirm et al., 2023 Japan Journal of Nursing Science |

|

|

|

Not surprising, there is some variability in the efficacy across different programs/interventions and across the three components of burnout.6 There are many variables that may affect effectiveness of burnout interventions in terms of the content of the initiative, and its primary target or level of intervention (see more on the methodological review of burnout intervention studies in the appendix). Overall, most of these articles (the vast majority of which were published) demonstrated that the interventions offer some reduction in burnout. However, although disappointing, it also may not be surprising that many meta-analyses and systematic reviews also concluded that there was considerable variability across the content, focus, and quality of interventions, such that results are either “inconclusive” or must be viewed with caution (e.g., Ahola et al., 2017; De Simone et al., 2021; Thomas Craig et al., 2021).

To better understand the details of the interventions used in these meta-analyses, Table D-2 highlights examples of individual and organizational interventions. Most of the current burnout intervention literature has typically used an “individual vs. organization-intervention” dichotomy. Individual interventions include programs aimed to support coping skills, resilience, and/or job skills, including communication and interpersonal skills. Organization-directed interventions involve changes to the job or work-environment, such as increasing work flexibility, reducing workload, providing additional resources, or more in-depth job and organizational redesign (De Simone et al., 2021). These interventions are further differentiated by the types of interventions within these two categories: Within individual interventions, most interventions in the meta-analyses involved cognitive/emotional support training, with some focusing on skills training, and a few on physical exercise (although many of the exercise interventions were part of the cognitive, emotional support training. Organizational interventions were divided into interpersonal interventions (e.g., group, leadership, interpersonal skills) and participatory job redesign and organizational change (e.g., job/work redesign, participatory action interventions, and organizational change).

Individual-Focused Interventions

Ironically, even though burnout is classified as a reaction to deficient or difficult workplace environments, most burnout interventions tend to

___________________

6 Many studies did not include CYN/DP and PE/PA, and as such many of the meta-analyses did not have sufficient studies to look at the effects of these two components of burnout.

TABLE D-2 Examples of Individual and Organizational Interventions to Address Burnout

| Types of Interventions | Levela | Example Studies | Example Programs/Intervention Componentsb |

|---|---|---|---|

| INDIVIDUAL | |||

| Cognitive/Relaxation/Emotional | |||

|

2° | Lloyd et al. (2013) |

|

|

2° | Li et al. (2023) -meta- |

|

| Physical | |||

|

2° | Ochentel et al. (2018) |

|

| Types of Interventions | Levela | Example Studies | Example Programs/Intervention Componentsb |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2° | Di Mario et al. (2023) |

|

| Skill Training | |||

|

1° | Cohen and Gagin (2005) |

|

|

1° | Schoeps et al. (2019) |

|

|

1° | Dyrbye et al. (2019) |

|

| Accommodation/Return to Work | |||

|

3° | Ahola et al. (2017) |

|

| Types of Interventions | Levela | Example Studies | Example Programs/Intervention Componentsb |

|---|---|---|---|

|

3° | Blonk et al. (2006) |

|

|

3° | Hätinen et al. (2013) |

|

| ORGANIZATIONAL | |||

| Interpersonal/Group | |||

|

1° | Le Blanc et al. (2007) |

|

| Types of Interventions | Levela | Example Studies | Example Programs/Intervention Componentsb |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1° | Peterson et al. (2008) |

|

| Leadership Training | |||

|

1° 1° | (few in-depth programs) Gilin et al. (2023) |

|

| (Participatory) Job Redesign & Organizational Change | |||

|

1° | Gregory et al. (2018) |

|

|

1° | Best et al. (2023) |

|

| Types of Interventions | Levela | Example Studies | Example Programs/Intervention Componentsb |

|---|---|---|---|

|

van Weert et al. (2005) |

|

|

|

1°- & 2°- | Hakanen et al. (2017) |

|

|

1° | Dyrbye et al. (2020) |

|

| Types of Interventions | Levela | Example Studies | Example Programs/Intervention Componentsb |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1° | Nielsen et al. (2021) Reduced burnout |

|

|

1° | Leiter et al. (2011, 2012) |

|

|

Dunn et al. (2007) |

|

| Types of Interventions | Levela | Example Studies | Example Programs/Intervention Componentsb |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Hung et al. (2018) |

|

|

|

Reid et al. (2010) |

|

|

| COMBINED/MULTI-FOCUSED | |||

| (not a specific ‘type’ of intervention per se, but interventions that explicitly combine individual and organizational interventions) | |||

|

1°/2° | Ansley et al. (2021) |

|

a Most studies did not specifically identify the level of intervention (primary, secondary, tertiary). Therefore, the level was inferred based on the description and goals of the interventions.

b These interventions are examples of programs within each of the intervention category that may provide insight for readers (and not necessarily the best of the category, but representative of programs within each specific category).

be individual focused (see Ahola et al., 2017; Awa et al., 2010; Maricuțoiu et al., 2016; Panagioti et al., 2017; West et al., 2016, for overviews), with the most common being CBT, mindfulness, and relaxation training. These types of individual training have a stress management focus and tend to adopt cognitive-behavioral related interventions or mindfulness “stress reduction” strategies, including counseling and relaxation techniques (see, Awa et al., 2010; Maricuțoiu et al., 2016). Relaxation training reduced EE across six studies in Maricuțoiu et al.’s (2016) meta-analysis.

Another interesting line of individual interventions involves skills-based individual training, including specific job skills training and development in terms of “soft” interpersonal and communication skills. Maricuțoiu et al.’s (2016) meta-analysis provided evidence to demonstrate the effectiveness of these types of programs overall. Typically, the interventions involved some form of group workshop or individual coaching sessions (or a combination of both).

Although examined to a much lesser degree, other types of job skills training may reduce burnout if the source of burnout is a lack of knowledge or skills (e.g., which may result in increased workload, poor productivity, errors, or safety incidents). Within the individual interventions, there are “skills development” both in terms of soft and job-specific skills. For example, role-related hard skills (i.e., job/skill training) reduced EE across the five studies in Maricuțoiu et al.’s (2016) meta-analysis. Training aimed at general hospital job skills for less experienced social workers significantly reduced burnout (Cohen and Gagin, 2005). These types of interventions may be considered as primary interventions, as they are aimed at reducing the source of the burnout (improved job skills, improved safety, etc.).

Interpersonal-Focused Interventions

Although burnout was initially conceptualized with service-industry workers having to deal with challenging interpersonal interactions (suggesting that burnout interventions should help improve these social interactions), few studies have examined interpersonal-based interventions7 directly, although there are some that look at training interpersonal skills (e.g., communication skills training) at an individual level. Interpersonal

___________________

7 Interpersonal interventions may be subsumed under organization-focused interventions. However, I use Nielsen et al.’s (2018) IGLO (individual, group, leader, and organization) categorization to create greater differentiation of the causes and potential targets of the intervention, which can help both researchers and practitioners study burnout and redesign workplaces.

soft skills increased PA across four studies in Maricuțoiu et al.’s (2016) meta-analysis.

In a participative, interpersonal-focused study reducing incivility and burnout (i.e., primary intervention), Leiter et al.’s (2011, 2012) group-based CREW (Civility, Respect, and Engagement at Work) intervention used an incivility intervention (that aimed to improve the social relationships and levels of civility in healthcare units). In general, incivility in the intervention units was reduced over the program, and it was unchanged in the control units. Through these reductions, the nurses also experienced decreased levels of job burnout in the intervention group (unchanged/increased in the control group), providing some support for the efficacy of tailored, interpersonal-focused interventions.

Leadership training also may be considered a type of primary intervention aimed at improving interpersonal relationships in organizations. Dyrbye et al. (2019) conducted coaching interventions via trained leader coaches for physicians on diverse topics such as building work support/community; addressing workload and work efficiency; optimizing meaning of work; developing leadership skills; and engaging in self-care. Compared with the control group, physicians in the intervention group had significantly greater reductions in EE scores from baseline to post-intervention. Moreover, they examined the proportion of physicians reporting high EE: After 5 months, the percentage of physicians from the intervention group reporting high burnout reduced by 19.5 percent (compared with a 9.8 percent increase in the control group). However, there were no statistically significant reductions in DP scores.

Finally, Le Blanc et al. (2007) implemented a team-based, participatory burnout intervention for healthcare providers (i.e., physicians, nurses, radiotherapy assistants) from 29 oncology wards in the Netherlands to improve team support (and to increase control and participation). The healthcare providers engaged in various activities (e.g., set team goals, identified issues, and developed actions plans; designated members to check in on team member’s well-being). The team intervention was successful in reducing both EE and DP. Compared with healthcare providers in the control teams/wards, healthcare providers in the intervention wards experienced lower EE and DP at Time 2 and lower EE at Time 3.

Organizational-Focused Interventions

Organizational interventions subsume many very different programs, typically defined by targeting some aspect(s) of the workplace (e.g.,

changing work environment) to reduce sources of burnout (e.g., workload; poor scheduling; poor interpersonal relationships) and increase resources to do one’s job (e.g., Soriano-Sànchez and Jimenez-Vazquez, 2023). The meta-analyses provided some support for organizational initiatives, although conclusions are not definitive about the efficacy of these programs. Given the extreme variability in the types of organizational interventions, it is not surprising that there would be a corresponding variability in their effectiveness.

Many of the organizational interventions have worker input into the design: For example, participative action research involves empowering employees to identify workplace stressors and develop and initiate solutions (de Wijn and van der Doef, 2022; Nielsen et al., 2021). Participatory action research may be effective as it “offers the opportunity for joint creation of meaning [such as] . . . shared mental models of what changes need to be made to the way work is organised, designed and managed, joint decision making and action to make such changes” (Nielsen et al., 2021, p. 391). Organizational interventions can include “lean principles” (optimizing workflow to reduce waste of resources; Hung et al., 2018) and increased participative management style to improve worker well-being (Van Bogaert et al., 2017).

Job crafting (i.e., changing one’s job role and/or interpersonal relationships, or increasing resources and decreasing demands; Tims and Bakker, 2010) may be viewed as an individual-, interpersonal-, or organizational-level initiative, depending on the exact focus and design. Several studies look at the effect of job-crafting interventions (empowering workers to make changes in their jobs and work environment) on burnout (e.g., emotional exhaustion; Gordon et al., 2018), improving social relations to reduce burnout (Yang et al., 2023), and the selection-optimization-compensation model as a process to job crafting (e.g., Müller et al., 2016).

Group Health implemented organizational changes to improve access, physician productivity, and financial performance of the organization. Although the program was successful in achieving access and productivity, it also increased physician burnout. In response to this increased burnout, Reid et al. (2010) examined the efficacy of a 2-year, quasi-experimental (before and after treatment, with a control group) program. This participative program involved workshops with all clinic staff (i.e., frontline physicians, managers, staff), patients, and researchers to identify “the redesign components that care teams refined and implemented during the first year” (p. 836). They then implemented best practices to address these

issues (e.g., reduced patient load, increase patient appointment times; daily team meeting/huddles). The “underlying premise is that care teams, led by primary-care physicians, retain accountability for delivering primary care to patients in their practices” (p. 836). Compared with the control group, the intervention group had significantly lower levels of EE and DP 24 months after the beginning of the program; however, there was no significant difference in PA scores.

Dunn et al. (2007) examined the effects of a 5-year organization intervention/change at a primary healthcare group, Legacy Health Clinic. Legacy Health expanded their key organizational outcomes to include physician well-being, such that they “prioritized physician well-being equal to care quality and financial viability” (p. 1545) and created initiatives to support this focus. Over the 5-year period, the changes to the work process resulted in significant decreases in levels of physician exhaustion, as well as reduced turnover (Dunn et al., 2007).

Combined Interventions

There is some evidence that interventions that combine individual and organizational focused initiatives may be effective in reducing burnout (Awa et al., 2010; Bes et al., 2023; Thomas Craig et al., 2021); however, overall, there is little evidence that they are more effective than individual/organizational alone. For example, some research suggests that multimodal programs are not successful (e.g., Estevez Cores et al., 2021). In their meta-analyses, De Simone et al. (2021) found that combined interventions were effective in reducing burnout, but organizational programs tended to have larger reductions in burnout.

Although somewhat speculative, there are a few potential reasons why combined interventions may be effective, including the following: (1) multiple issues are being addressed simultaneously (e.g., reducing work/organizational demands, improving group functioning and relationships, improving individual skills and coping), thus addressing the complexity of burnout antecedents; (2) an organization’s engagement in creating combined initiatives may reflect their commitment to improving worker well-being, thus creating additional (and potentially unmeasured) supports for employees; and (3) having multiple aspects of the program may increase the overall “dosage” of the intervention. That is, participants may be more involved and spend more time addressing burnout from various standpoints, thus resulting in a higher treatment/dosage.

SUMMARY OF BURNOUT INTERVENTIONS

The review of burnout meta-analyses is far from conclusive, but it provided evidence for both individual and organizational-based initiatives, typically with individual-focused ones having some stronger results. However, some meta-analyses have found that having combined individual-organization initiatives are the most effective (e.g., Bes et al., 2023). Dreison et al. (2018) also noted a need for more studies evaluating this combined intervention approach and organizational interventions, beyond simply job training/education. That is, not all (organizational) interventions are equal, either in the quality of the intervention process or in its content. Moreover, the number of studies focusing on individual interventions far outnumbers the ones on organizational interventions (e.g., Bes et al., 2023; de Wijn and van der Doef, 2022).

Dreison et al. (2018) has called for more research looking at multiple ways of addressing burnout. This multifaceted approach also has the benefit of addressing the burnout intervention dilemma, such that focusing on multiple aspects of the sources of burnout could improve both the workplace and individual functioning. Only when we can create this holistic focus can we truly address job burnout and reduce the sources of burnout.

Therefore, from the evidence across these meta-analyses and interventions studies, it is obvious that there may be no “one” correct answer: That is, program efficacy may depend on the specific details of the intervention and organizational context, as well as the sample characteristics and the sources of the burnout. In general, it may be folly to think that burnout is always explained solely by a single factor. Instead, we must appreciate the complex interplay of individual, group, leader, and organizational antecedents that create environmental demands, as well as individual responses to these demands, that can lead to burnout. Therefore, a key aspect in addressing burnout is understanding burnout in the specific context. For example, Leiter et al. (2011) conducted an intervention to address a specific problem of incivility and poor collegial relationships in hospital workgroups, which was leading to burnout and other negative organizational outcomes. It also included supportive team activities, and a team facilitator. By using a participatory method to help teams identify their specific sources of burnout, the program allowed activities to be tailored to reduce incivility and thus reduce burnout. These types of tailored intervention, which focus on the source of the burnout, allowing participatory input into the design and solutions, and allowing for support for individuals, may be integral in making significant progress in burnout intervention research and practice.

DISCUSSION

The field [of burnout interventions] has made limited progress in ameliorating mental health provider burnout. Based on our findings, we suggest that researchers implement a wider breadth of interventions that are tailored to address unique organizational and staff needs and that incorporate longer follow-up periods.

– Dreison et al., 2018, p.18

This current review supports Dreison et al.’s conclusions about the state of the burnout intervention research. Despite the abundance of studies on burnout in general, the relative number of high-quality organizational-based intervention studies is low. Moreover, there are inconsistencies in findings across the studies, and many of them are plagued by bias and methodological issues. These problems are not necessarily surprising given the challenges involved in conducting high-quality organizational interventions aimed at changing the work environment to support workers. However, these studies, along with their quality and conceptual issues, can provide insights and (some cautious) suggestions for future research and organizational practice in addressing burnout and supporting worker health.

First, it is valuable to understand the rationale as to why there is this disconnect between having organizational sources of burnout and proposing individual solutions for burnout. That is, to address burnout we need an understanding of the possible reasons for the lack of validated interventions. Several reasons are suggested by the literature: (1) a lack of awareness about the problem and solutions; (2) a lack of organizational culpability; (3) organizational inertia (and lack of expertise); (4); burned-out leaders; and (5) practical issues (cost; access; productivity pressures).

Lack of Awareness/Knowledge

Leaders may not fully understand the sources of burnout and may view individual-based, resilience-building as a legitimate fix rather than a mere band-aid step in covering deeper organizational-based issues. Indeed, research shows that individual-focused interventions can help. Thus, the awareness and impetus for organizational change is decreased. Therefore, continued communication about the sources of burnout, along with ways organizations can address it, is critical.

Blame and Culpability

Even with general awareness of the causes of burnout, the organization must explicitly accept culpability that the workplace is a key source of the burnout. It is much easier (and cheaper, see below) to place the ‘blame’ on the employees. By framing burnout as an individual worker problem, organizations that prioritize productivity and efficiency (even at the expense of worker well-being) do not have to examine deeper, systemic issues like toxic work cultures, unrealistic expectations, or inadequate support structures and change fundamental business practices.

By blaming employees, organizations: (a) do not have to acknowledge their own responsibility in the role of burnout; (b) do not engage in organizational change mechanisms; and (c) do not have to design and implement (potentially seemingly costly and time-consuming) organizational change strategies. Basically, they can continue with business as usual, with the employee—not the employer—paying the cost. In essence, pushing employees may benefit the organization, or at least do so in the short-term (Walker, 2025). Getting organizations to accept responsibility is the most difficult rationales to overcome. Finding a champion at senior management levels may be an effective way forward.

Organizational Inertia

Even if there is an awareness and acceptance of the role the organization plays in burnout, organizational inertia is a powerful force to overcome. Organizational change is a challenging process, and the status quo can be affirming and safe. When there is a focus on short-term, rather than long-term, goals, leaders may argue that it makes procedural and fiscal sense to fix people rather than the organization. Therefore, there must be a concerted effort, preferably with a champion and upper management support, to identify and implement the required change. Importantly, part of the inertia may be related to a lack of expertise to identify and implement organizational strategies to engage in change. Having access to people knowledgeable in validation techniques (e.g., internal consultants; I/O psychology consultants; graduate students/faculty; etc.) could help them to identify, develop, and validate key strategies for the workplace. There are other reasons for this inertia including a perceived lack of organizational resources.

Burned Out Leaders

One of these organizational resources is the required personnel to create change. The role of creating change rests largely on leaders. Ironically, because leaders are operating in the same environment, there is a good chance they are overwhelmed and burned out as well. This depletion of energy and focus detracts from their ability to create effective organizational change. This becomes a Catch-22, such that we need energized and effective leadership to create organizational change to reduce burnout, but the leaders are too burned out to create the change that would ultimately reduce their burnout. That is, reducing burnout requires effective leadership, but burnout itself prevents leaders from being effective.

Practical Change Issues

As noted above, inertia can arise from the practical issues, such as a lack of access to experts, effective leadership, and fiscal resources, or a conflicting long-term organizational vision. Structural changes to reduce the sources of burnout—such as reducing workloads, increasing staffing, or modifying job expectations—can be expensive and require long-term investment. Conversely, training employees in mindfulness, stress management, or resilience is relatively cheaper and quicker to implement than overhauling work policies. Moreover, there are psychological constraints to overcome: Change is scary and perceived to be expensive and time-consuming, such that smaller and equally efficient changes are often overlooked. However, small and cheap changes can be effective: We often challenge organizations to think of how small and cheap changes can be effective. For example, mistreatment is a key source of burnout, but treating employees with respect is free.

Collectively, these rationales for not pursuing organizational interventions to reduce the sources of burnout can negate attempts to address the burnout problem. Understanding, and overcoming, these rationales can help ensure the success of existing organizational interventions as well as create new approaches to this old problem.

Novel Approaches to Addressing Burnout

Part of the original purpose of this paper was to identify unique, innovative initiatives to address burnout. However, once immersed in the

literature, and having identified some of the key sources, it becomes apparent that the search for unique “cures” to burnout is unrealistic. Expecting one single, definitive cure for burnout, given that it is influenced by a wide array of individual and organizational factors, is not feasible.

Moreover, searching for novel ways to address burnout may once again divert attention away from the underlying tenets of burnout in targeting primary initiatives aimed at reducing sources of burnout. However, this review identified effective interventions and processes, and in identifying some of the gaps, it has provided some novel ways at looking at burnout interventions. Therefore, in looking at unique ways of addressing burnout, we must (1) accurately assess both the sources of burnout and the extent to which workers are burned out; (2) envision burnout interventions as holistic, participatory processes/strategies, rather than individual programs (e.g., BUILDs process model, as described later in this section); which leads to (3) tailoring burnout interventions at the organizational, group, and individual levels by (a) identifying the specific sources of job burnout, and creating primary interventions to address these sources, (b) offering secondary interventions to help workers deal with ways of managing these stressors, (c) maintaining tertiary supports, which helps us to (d) create multifocal, combined interventions; and (4) understand and measure the exposure/strength/dosage of programs.

Addressing Burnout and Its Sources

We need to clarify the language for understanding and measuring sources of burnout versus assessing symptoms of burnout. Although there is relative consistency in the meta-analyses in how to assess burnout EE, CYN/DP, and PA/PE symptoms (most studies used the MBI), there is little mention of validly identifying and measuring the sources of burnout, even though many valid measures are available (e.g., leadership, bullying). More work must focus on understanding/measuring these sources with respect to burnout.

Moreover, in some research, burnout was conflated with stress, strain, and/or general fatigue. We must maintain the distinction between burnout (as a three-phase syndrome in response to poor organizational environments) and more general strain response (physical, psychological, and behavioural outcomes to stressors). Some studies only use EE, ignoring the DP/CYN and PA/PE components, providing an incomplete (and potentially misleading) indicator of the entirety of burnout. Finally, some studies used a one-item

self-report scale as to how much people feel they are burned out, which not only fails to assess the three components of the burnout construct but also relies heavily on individual interpretation of what burnout is supposed to be.

‘BUILD’ing Participatory Organizational Burnout Strategies

A primary focus on novel content of interventions distracts from an overall organizational burnout process/strategy. That is, as demonstrated by participatory organizational intervention process steps (e.g., Nielsen et al., 2021), a process/strategy provides a template for organizational leaders and employees to develop action plans to address their specific demands (using their specific resources) to help maintain and improve employee functioning.

Therefore, regardless of the interventions used, organizations must have a process to accurately assess their status quo, in terms of their employees’ levels of burnout, and the specific sources of burnout (as well as intervention effectiveness). Because the organizational sources of burnout are varied, organizations need to design interventions around the specific sources within their organization and have specific supports in place. Also, having a means to gather input and feedback from employees is integral to the intervention process. What works for one individual or environment may not work in the another. Using process models, such as the BUILDs model (Day, 2019) can help identify steps in addressing burnout at all levels. It involves getting buy-in from stakeholders, in terms of understanding the importance of measurement and burnout initiatives. Understanding and assessing the organizations’ status quo, in terms of their employees’ levels of burnout, and understanding that the specific sources of burnout are key steps in resolving burnout. Once the sources are identified, identifying and implementing key, targeted interventions are critical. Finally, organizations must support ongoing learning, getting feedback on program efficacy, and developing sustainability in organizational learning to support work well-being via continuous improvement and development processes. These types of processes help create meaningful, tailored initiatives to reduce sources of burnout, support employees, and manage employees’ experience of burnout.

Tailoring Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Interventions

Using a participatory process model also can help the overall organization understand the sources and outcomes of burnout to help tailor the program to the organizational context and to the individual. That is, different

facets of the workplace can impact worker burnout, such that “one size” of burnout intervention does not “fit all” instances of burnout. Abildgaard et al. (2019) lobbied for participatory organizational interventions, because they create “multiple intervention mechanisms interacting with the specific organizational contexts” (p. 1339).

Moreover, success of initiatives may vary across workers because the workers and leaders involved in organizational interventions may perceive the same intervention very differently (Bartunek et al., 2006). Therefore, more work is necessary to understand variations in perceptions of interventions, as well as intervention efficacy, based on key work (e.g., organizational level; industry) and individual characteristics (e.g., gender; race/ethnicity). However, if organizations take a truly individual-focused, tailored approach to addressing burnout, these individual differences transcend these group categorical data.

A participatory process also may help resolve the individual versus organizational debate; that is, as noted throughout this review, burnout is defined as a reaction to poor work environment and chronic workplace issues. As such, Maslach and Leiter (1997) have argued a need for organizational interventions to reduce these sources of burnout, and not simply ask workers to rethink how they respond to them. However, most interventions focus on secondary interventions (e.g., helping individuals develop coping mechanisms) rather than on primary interventions (i.e., changing the source of the burnout).

This situation may not be surprising given the challenges involved in conducting high-quality organizational interventions aimed at changing the work environment to support workers. Organizational interventions are complex, time-consuming, expensive, and hard to design (Gregory et al., 2018), and it is cheaper and easier to focus on supporting individuals rather than changing systems. That is, it is far easier to ask employees to develop stronger demand/stressor-management techniques (CBT, mindfulness) and “be less burned out” than to identify and reduce the sources of burnout (e.g., reduce workload, improve leadership, reduce patient/client/coworker incivility). However, it creates the key dilemma in addressing burnout by using secondary interventions to manage demands that could be reduced through primary prevention interventions.

In Valcour’s (2016) Harvard Business Review article on practical advice to reduce burnout, the three tips she provides to clients all focus on individual care factors: (1) prioritize self care, (2) shift your perspective, and (3) reduce exposure to job stressors. However, she provides the very

important caveat up front that “situational factors are the biggest contributors to burnout, so changes at the job, team, or organizational level are often required to address all the underlying issues. However, there are steps you can take on your own once you’re aware of the symptoms and of what might be causing them.” That is, we need to first improve the cause of job burnout (i.e., the workplace environment), and while that is happening, we can support and develop how employees are able to handle the fallout from job stressors and the resultant burnout.

Similarly, in their study of physician burnout, Gregory et al. (2018) noted that although these types of individually focused self-care programs “have shown a positive effect on reducing burnout, this intervention approach is inconsistent with the underlying theoretical framework for burnout” (p. 341). Therefore, they concluded that even though improving physician resilience “may be an important skill to develop . . . organizationally focused interventions that improve the practice of medicine within organizations is the optimal way to reduce physician burnout” (p. 342; emphasis added).

Primary Interventions: Understanding and Reducing Burnout Sources. As a relatively simple, yet integral, start for both researchers and practitioners, instead of talking about addressing or even reducing burnout (which implies more of a secondary/tertiary management of individual-focused conditions), we must start talking about reducing the sources of burnout (i.e., primary prevention). This simple change of phrase reflects a greater underlying difference in perspectives: Job burnout is, and should continue to be, defined as a syndrome resulting from exposure to work demands, many of which are manageable. As such, we need to stop thinking about burnout as an individual problem and go back to making it an organizational problem.

One understudied method for reducing burnout pertains to the area of recruitment, selection, and training, even though research has demonstrated the key aspect of having a “match” between the individual and the job. Leiter and Maslach’s (1999) work on the perceived congruency between the individual and key aspects of his or her organizational environment help us understand how burnout can arise from a mismatch between individual and organization. They proposed that the greater the perceived misalignment between the individual and their job, the higher the likelihood of burnout; conversely, the greater the perceived alignment, the higher the likelihood of feeling more engaged with work. That is, the “degree of perceived congruency between the individual and key aspects of [one’s] organizational

environment” can influence one’s level of burnout (Maslach and Leiter, 2008, p. 501).

Nurses’ perceived fit tends to be related to EE, and it also can moderate the relationship between empowerment and EE (e.g., Laschinger et al., 2006). This area has important implications for ways to reduce the sources of burnout: That is, if a person-job/work fit is key to well-being on the job, effective selection methods that assess this fit are essential. However, we see very little work incorporating human resource activities (e.g., recruitment, selection, training) in preventing burnout. A caveat is warranted here: This fit does not denote hiring people who are better able to handle unreasonable organizational demands. For example, organizations still must eliminate sources of supervisor, client, and colleague mistreatment burnout in the workplace. Congruency is meant to ensure that there is alignment in what is legitimately required by the job and key competencies of the incumbent.

Secondary Interventions. Despite a push toward organizational interventions, individual interventions have been shown to be very effective. They often help reduce strain outcomes and burnout, which makes sense. If you are not in control of the stressor and no one else is doing anything to reduce it, there are several possible outcomes: you can leave the organization, “deal with it” (effectively or ineffectively), and/or get sick. Therefore, being better able to deal with it can help you to function and feel better. However, should we be asking workers to develop better coping and recovery techniques to deal with the sources of burnout, such as bullying, overload, and lack of support and autonomy? Or should we strive to improve the work environment to minimize these demands? That is, although secondary approaches show promise in reducing strain and burnout (and although there are some innovative methodologies being offered on apps that can increase the visibility and accessibility of burnout programs), we still must use it as a secondary step, after we have reduced the sources.

Tertiary Interventions. Although advocating for primary and secondary interventions, tertiary interventions are still required. That is, despite best efforts, some people may still experience mild to severe burnout. Therefore, Maslach and Leiter (2008) argued that it can be valuable to look at burnout in a different, more pragmatic way by examining early indicators of burnout in workers:

If such early indicators were indeed valid predictors of future problems with burnout, then they could be used to identify “high risk” people who could be targeted for early, preventive interventions. This approach is a purely pragmatic one, which simply focuses on

people’s experiences at particular points in time rather than making other assumptions or including other variables. The basic premise is that if an individual is experiencing some early signs of burnout, then that information is sufficient for consideration of actions to prevent burnout and build engagement (p. 498).

This perspective does not blame the individual, but it considers the workers’ current state (from the interaction between self and work environment) and strives to prevent severe burnout by understanding and addressing these warning signs.

Holistic Multifocused Interventions

Given the value of all three levels of interventions, a systematic way to incorporate all levels, creating a holistic multifocused burnout strategy, is warranted. That is, the intent is to focus on reducing the negative aspects of the organizational environment that are creating burnout, while still supporting individual workers in how they handle work challenges. In Schein’s (1990) model of organization culture, he highlights the difference between artifacts (surface indicators of culture) and underlying values and basic assumptions of the organization. Innovative techniques or initiatives (i.e., surface-level artifacts) can be insufficient in reducing burnout if the organizational culture does not reflect an authentic, underlying value of its workers (e.g., views workers as disposable resources rather than a valuable commodity).

For example, in Dunn et al.’s (2007) organizational intervention across several healthcare facilities, management made physician well-being a priority on par with the facilities’ financial outcomes; that is, well-being was as important as profits. This action was rooted in changed underlying values, going beyond being a simply surface-level artifact to being a key driver in how they viewed physician health, the decisions they made, and additional actions they took to support physicians.

A caveat regarding using primary interventions (e.g., organizational change) is that, ironically, organizational change—even change for the better—can be challenging and contribute to worker stress (Day et al., 2017). That is, change to improve the workplace (e.g., Reid et al., 2010) and organizational interventions designed to reduce burnout (Van Bogaert et al., 2017) can have the unintended effects of increasing burnout.

However, Day et al. (2017) also found that control and support can buffer the negative effects of perceived change-related stressors on employees’ burnout. Therefore, including participatory components may improve

autonomy and increase supports while reducing change-related stressors. Similarly, using combined interventions—using both primary and secondary interventions—may help reduce individual strain/burnout during the longer-term change process. For example, when implementing organizational interventions aimed at reducing the sources of burnout, include participatory processes to ensure the change is tailored to the situation and individuals and incorporate ways of supporting employees and leaders through the change. A reduction in leaders’ stress can reduce followers’ level of burnout as well (Harms et al., 2017).

Strength and Quality of Interventions

A final consideration in developing burnout interventions is the strength (or “dosage”/exposure) of the intervention. Participants in the same intervention may have different dosages or exposure to the intervention, in the number of sessions attended, level of engagement, time spent on practicing new skills, and so forth. It is not always practical (or desired) to standardize the dosage across participants, but measuring dosage, or proxies of dosage, wherever possible is helpful. For example, as part of the CREW intervention (aimed at reducing incivility and burnout), hospital units tailored activities to meet their specific needs. This tailored and participatory nature of CREW added to its efficacy, but it also created ambiguity as to the dosage that each unit was receiving. In response, Leiter et al. (2011) examined the strength of intervention, finding there were no differences in burnout based on the different programs across the eight units. Conversely, de Wijn and van der Doef (2022) found a significant effect of exposure to intervention, such that studies in which nurses participated in most of the intervention sessions had higher effect sizes than did studies in which the sample had a lower participation/exposure. Therefore, some type of measure of intervention strength, exposure, or dosage should be included in burnout intervention studies.

Another way to think of dosage is in terms of organizational resources put toward the initiatives. Van Bogaert et al. (2017) concluded that “it is not surprising that the sites that have invested the most, in terms of financial human resources and facilitation have yielded the most improvements” (p. 34). Therefore, incorporating ways of increasing organizational, leader, and group efforts into the interventions, and integrating them into the operations of the organization, may create more beneficial outcomes.

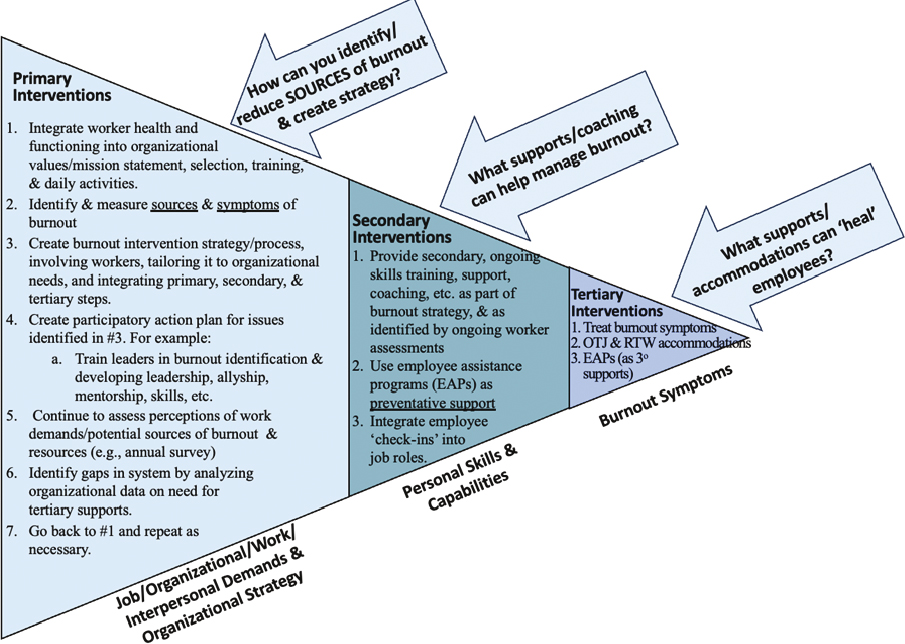

A template for a holistic workplace burnout strategy for burnout based on all the above areas is presented in Figure D-2. It highlights some

potential examples of primary, secondary, and tertiary initiatives that an organization can undertake to concurrently address organizational change and employee functioning. In line with most intervention frameworks, it outlines an initial (and predominant) use of primary interventions, followed by the use of secondary interventions. Ideally, tertiary interventions are seen, and used, as the last step in situations where primary and secondary interventions were not sufficient to reduce sources of burnout and help develop supports/resources for workers. Although (hopefully) used to a lesser extent, their important role in addressing the fallout from burnout is still essential.

CONCLUDING COMMENTS

There have been considerable steps made in understanding the causes of burnout, and substantial increases in recent years in secondary-level individual-focused interventions to address burnout via individual coping skills. However, it has been well documented that despite a general agreement that burnout arises from organizational causes, there are few validated organizational interventions. Moreover, these types of interventions also have greater variability around their content (e.g., interpersonal group initiatives, leadership development, work process changes) and goals (e.g., create manageable workloads, create better work relationships), which make it challenging to make solid conclusions about their effectiveness.

Understanding and directly addressing this disconnect between having organizational sources of burnout and proposing individual solutions for burnout can improve usage of organizational initiatives to reduce the causes of burnout. Organizations can improve awareness about the problem and identifying organizational solutions. They should ensure accountability for their own actions. They need to understand the underlying causes of organizational inertia (including a lack of expertise). Ironically, they must ensure their leaders are healthy and not burned-out to be able to support employees and create organizational change. Finally, they must provide resources to address the root causes of burnout, and still not catastrophize the problem so that it becomes seemingly insurmountable.

Interestingly, some of the key insights from the meta-analyses arise not from the data per se, but from the assumptions made in the studies, and some of the biases and violations of the assumptions. For example, (1) we need to be clear about what we mean my burnout: burnout, stress, and strain are all important worker outcomes and are related to each other, but it is meaningful to keep them distinct. Moreover, we need to look at

the full construct of burnout beyond emotional exhaustion (including depersonalization/cynicism and personal accomplishment/professional efficacy). (2) If we accept that the etiology of burnout is multifactorial, we also need to accept that there is no one overall panacea to prevent and reduce burnout. The use of individual-focused programs alone is antithetical to the definition of burnout, and it ignores the work sources of burnout. Thus, although mindfulness may help us get through multiple work (and nonwork) events across our lifetime, it is not the cure for those events. Targeting the actual events (reduce workplace bullying, improve client interactions) is much more effective that looking at ways to handle our reactions. That is, we must stop having a sole focus on managing worker symptoms and start reducing specific workplace sources of burnout. (3) Trying to find novel ways to reduce burnout may impede our ability to reduce both sources and symptoms of burnout. We may prefer novel and quick-fix solutions, yet the tried-and-true (and perhaps more long-term and challenging) option is still more effective. That is, if the causes of burnout are systemic within the organization, reducing burnout requires long-term changes to organizational culture to reduce the root causes of burnout. Therefore, (4) organizations can achieve these goals by creating an overall introspective burnout strategy, which focuses on the root organizational causes of burnout and which values worker well-being and functioning.

REFERENCES

*indicates a meta-analysis of burnout interventions

Abildgaard, J. S., Nielsen, K., Wåhlin-Jacobsen, C. D., Maltesen, T., Christensen, K. B., & Holtermann, A. (2019). “Same, but different”: A mixed-methods realist evaluation of a cluster-randomized controlled participatory organizational intervention. Human Relations, 73(10), 1339–1365.

*Ahola, K., Toppinen-Tanner, S., & Seppänen, J. (2017). Interventions to alleviate burnout symptoms and to support return to work among employees with burnout: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Burnout Research, 4, 1–11.

Ansley, B. M., Houchins, D. E., Varjas, K., Roach, A., Patterson, D., & Hendrick, R. (2021). The impact of an online stress intervention on burnout and teacher efficacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 98, 103251.

Aronsson, G., Theorell, T., Grape, T., Hammarström, A., Hogstedt, C., Marteinsdottir, I., Skoog, I., Träskman-Bendz, L., & Hall, C. (2017). A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health, 17, 1–13.

Awa, W. L., Plaumann, M., & Walter, U. (2010). Burnout prevention: A review of intervention programs. Patient Education and Counseling, 78(2), 184–190.

Bakker, A.B. (2009). The crossover of burnout and its relation to partner health. Stress and Health, 25(4), 343–353.

Bartunek, J. M., Rousseau, D. M., Rudolph, J. W., & DePalma, J. A. (2006). On the receiving end: Sensemaking, emotion, and assessments of an organizational change initiated by others. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 42(2), 182–206.

*Beames, J. R., Spanos, S., Roberts, A., McGillivray, L., Li, S., Newby, J. M., Bridianne, O., & Werner-Seidler, A. (2023). Intervention programs targeting the mental health, professional burnout, and/or wellbeing of school teachers: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Educational Psychology Review, 35(1), 26.