Impact of Burnout on the STEMM Workforce: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 6 Current and Innovative Approaches to Managing Burnout

6

Current and Innovative Approaches to Managing Burnout

Highlights from the Presentations

- Most current interventions as well as current research on interventions focus on supporting individuals rather than changing environments (Day).

- A holistic approach to addressing burnout considers four areas: Individual, Group, Leader, and Overall Organization, or IGLOO (Day).

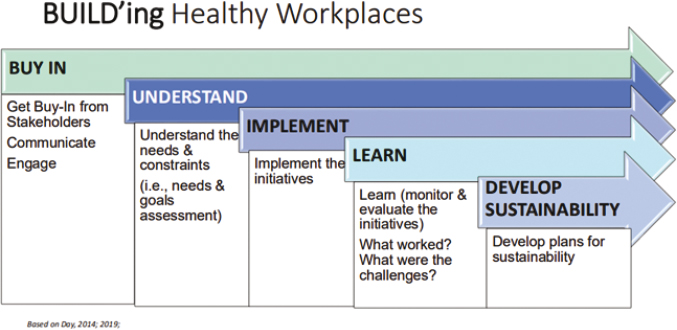

- One potentially fruitful model to introduce an intervention within an organization is the BUILD model, which encompasses Buy-in, Understand, Implement, Learn, and Develop sustainability (Day).

- As an analogy to burnout as a job hazard, a broken wrist or concussion from a fall can be treated, people can learn to watch for and avoid hazards, but, ideally, the hazard is removed (Day).

- A fallacy in the realm of policy is that easy tips and tricks will solve more complex challenges. Deeper investments are required (Adibe).1

- Unless and until the economic basis of burnout is addressed, rather than addressing it for altruistic reasons, interventions will be limited (Adibe).

The second day of the workshop turned from understanding the causes and consequences of burnout in science, technology, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM) to interventions. To launch the day, attendees took a quick online poll to rate the efficacy of current interventions. None saw current interventions as very effective, 62 percent saw them as somewhat effective, and 38 percent saw them as not effective. In sharing the poll results, planning committee chair Reshma Jagsi (Emory University) commented, “Maybe the discussions from yesterday show the reasons why. One size does not fit all.”

Alicia Kowalski (University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center) then moderated a session on current and innovate approaches to managing burnout that began with a presentation by Arla Day (St. Mary’s University) based on a commissioned paper. (See Appendix D for the full paper.) Bryant Adibe (Princeton University) served as discussant, followed by open discussion.

This paper was commissioned to provide current knowledge on effective interventions to address burnout in terms of both policies and practices that support those experiencing burnout and work to proactively mitigate burnout. In discussions with the author while planning this paper, it was determined that limiting to only interventions tested within STEMM would provide an incomplete picture. The decision instead was made to focus generally on a framework for understanding different types of interventions that could be employed in STEMM fields.

___________________

1 While speakers on Day 1 noted the value of addressing small “pebbles in the shoe” as meaningful but low-cost ways to address burnout, speakers in this panel were more divided. There was acknowledgment that smaller efforts can make a difference but also concern about focusing too much on the idea that individual nudges could accumulate and change societal problems significantly when deep investments are needed.

ADDRESSING BURNOUT

Day drew on the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of burnout, and noted it is an occupational syndrome that leads not only to exhaustion but also to cynicism and lack of accomplishment. She underscored the six causes elucidated by Christina Maslach and Michael Leiter (see Chapter 2). Workload alone does not create burnout. Although not the simple answer that one might wish for, it is caused by many things and is very context dependent. Research shows it comes from workload combined with (1) a lack of autonomy and control; (2) interpersonal relationships related to lack of work support, community breakdown, bullying and ostracism (e.g., Thompson et al., 2020), and incivility (Leiter et al., 2011, 2012); (3) organizational changes (Day et al., 2017); and (4) lack of transformational leadership (Day and Hartling, 2016). Outside the workplace, burnout can come indirectly from additional demands placed by friends and family and from within oneself (Bakker and de Vries, 2020; Hakanen et al., 2011).

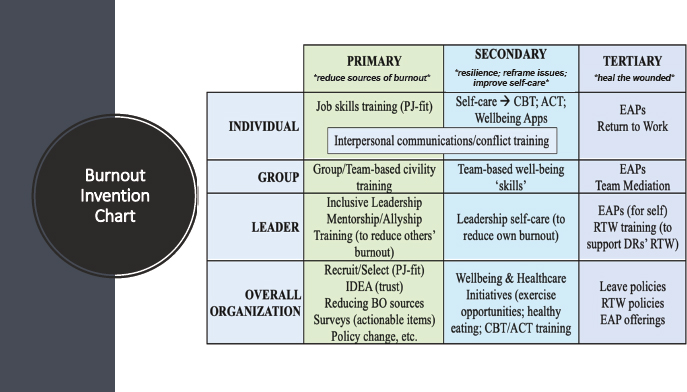

Two general ways to address burnout are to focus on the symptoms or focus on the sources. Addressing symptoms might involve caring for workers who have burnout (e.g., through counseling, leave, and resources for resiliency). Addressing the sources involves reducing the organizational causes and not just “healing the wounded.” She likened interventions to primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of medicine. For burnout, she suggested, the tertiary level would be to treat the symptoms, the secondary level would be to change perceptions and strengthen coping skills and resilience, and the primary level would be to change the environment through increased resources and decreased demands.

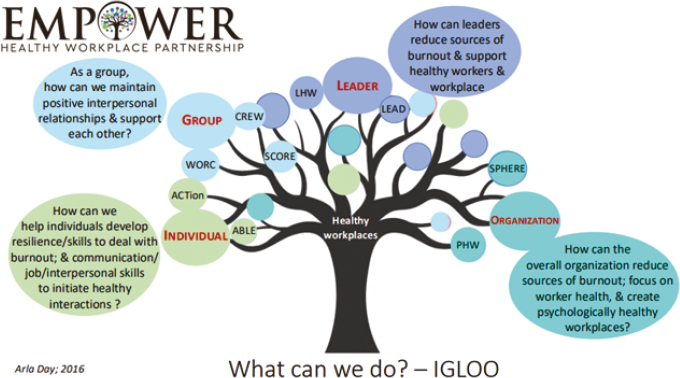

She offered another framework from the EMPOWER Healthy Workplace Partnership, with interventions at the levels of Individual, Group, Leader, Overall Organization, or IGLOO (see Figure 6-1). Approaches must be holistic, she stressed, so that all four levels are considered.

Elaborating on the framework, most interventions that are implemented and have been studied in the scientific literature are individual based, such as mindfulness and therapy to change perceptions of the workplace and improve coping and resilience. Other individual-focused interventions include family and friend support, healthy eating and sleeping practices, and delegation of responsibility.

Group- or team-focused interventions aim to maintain positive relationships, such as CREW (Civility, Respect, and Engagement in the

SOURCE: Arla Day, Workshop Presentation, October 2, 2024.

Workplace), led by Michael Leiter (Osatuke et al., 2013). Day explained the CREW framework was not specifically designed to reduce burnout, but it has been shown to improve workplace relationships and reduce burnout. She stressed CREW must be tailored to a specific work unit and implemented through a participatory process. The members of the unit decide the issues to tackle and what constitutes appropriate behavior.

Moving to leader-focused interventions, Day described a study in a West Coast healthcare system in which management allowed physicians to identify key issues and how to fix them. One thing that emerged was to place physicians’ health on par with financial performance as a priority. Leaders can also support mentorship and allyship, bring teams together, and treat all team members with respect. These actions will not change whole systems, but they also do not cost a lot. As she posed, how much does it cost to treat employees with respect? Little steps can lead to larger ways of well-being and lower burnout. Leadership self-care should also be incorporated into training, she continued. Leaders need to care for themselves and learn how to support their team’s well-being.

Organizational-focused interventions are varied and can take many approaches. She noted that one topic on which she wanted to see greater work that arose on the first day of the workshop was the issue of person-job fit. From an organizational perspective, she noted that this was important

SOURCE: Arla Day, Workshop Presentation, October 2, 2024.

in recruiting and training employees and giving them what they need to do their jobs. People are less burned out when they do things effectively.

Pulling together the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels, and IGLOO, Day offered a menu of potential interventions (see Figure 6-2). This menu highlights that burnout can be addressed at three levels. At the primary level, interventions can work to reduce the actual sources of burnout. At the secondary level, interventions can aim to improve resilience to experiencing burnout. At the tertiary level, interventions can respond to those who are already burned out. Interventions at each of these levels can operate across different groups or targets of the intervention. That is, a primary intervention addressing causes of burnout may target individuals by providing job skills training that helps them engage in their work more effectively and efficiently but could also target leadership by having leaders engage in mentorship training that may improve how they are engaging with employees. Overall, the model highlights the multiple levels and potential targets of interventions and what types of interventions sit at each intersection.

Where to start to create healthy workplaces? Day offered the idea of a BUILD model: Buy-in, Understand, Implement, Learn, and Develop Sustainability (see Figure 6-3). The model begins with gaining buy-in from key constituencies and engaging supporters to advance change. Next, the goal is to increase understanding—what are the needs and constraints of the

SOURCE: Arla Day, Workshop Presentation, October 2, 2024.

workforce that need to be addressed? From there, the next step is to take this knowledge and implement an initiative aimed at addressing the key pebbles in the shoe. After implementation, Day argued, it is important to learn and evaluate what worked and what did not. Finally, the goal is to develop sustainability to ensure that new and successful initiatives remain in place.

As key take-home messages, Day summarized that (1) burnout is not just emotional exhaustion but affects job performance; (2) most current interventions focus on supporting individuals, rather than changing the environment; (3) the best interventions are those that do not focus on the syndrome per se but on the causes; (4) there are no simple cure-alls to burnout, though there are simple actions that can be taken to improve environments; and (5) an ongoing process must be built. As an analogy to burnout as a job hazard, she noted that while a broken wrist or concussion from a fall can be treated and people can learn to avoid hazards, ideally, the hazard is removed so no one is at risk of injury in the first place.

REFLECTIONS

Kowalski highlighted Day’s observation about the lack of interventions and best practices at the organizational level and asked how more can be done. Day suggested looking at European organizations that tend to do better in this regard. She called for encouraging organizations to look broadly and to change the culture to realize the benefits and value of reducing burnout.

Adibe agreed that looking at organizational versus individual interventions is critical and noted some evolution in the literature over the past 20 or so years. Abide expressed skepticism that small “nudges” in individual behavior and fixes could have a broader impact. The nudge effect or nudge theory comes from a 2008 book from Richard Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein and posited that environments could be adapted in ways that influence how individuals and groups make decisions and potentially address larger societal problems such as choices in health or retirement (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008). In response to this theory, “nudge units” were set up both in the United States and abroad, with the hope that individual-level interventions could solve larger societal problems at less cost and social capital. Cumulative data show they have had limited impact. A 2022 systemic review by two proponents of the nudge effect showed an effect size of 1 percent or less (Chater and Loewenstein, in press).

In his view, a fallacy in the realm of policy is that easy tips and tricks or quick wins will solve more complex challenges. He argued that deeper investments are required, and burnout serves as an example. Some studies show that another effect of the focus on individual interventions is decreased public support for broader societal solutions. Without addressing core systemic issues, it will be tough to fight burnout, he said. He expressed some optimism that once it is recognized that societal-level problems cannot be solved by individual-level interventions, tools can be developed to investigate what he called the “well-being black box.” He and his team, for example, have developed a tool to help organizations understand the economic and other drivers of burnout within their system and provide recommendations for the organization to get at the root of them. “This allows the organization at the system level to provide better solutions and more closely mirrors what frontline providers actually want,” he said.

Day reiterated the point that rather than more research on the causes, efforts should be focused on organizations using tools in their specific context. Longitudinal work is also needed. There are no quick wins to the broader challenges producing burnout but instead a need to focus on the long term. She said she has optimistic and pessimistic perspectives. On the optimistic side, people want to and are thinking of how to tackle burnout. Pessimistically, she questions if organizations, and the people within them, really want to change.

Kowalski commented that many interventions are reactive, although more should be proactive. Day said a focus on the reactive might have limited outcomes. From a healthcare lens, Adibe commented that people

are in a reactive state because healthcare organizations are in a tough period economically. With declines in revenue, leaders may reduce staffing ratios, by decreasing administrative support or increasing productivity by raising Relative Value Units, or RVUs, thresholds.2 This gap drives burnout, but unless and until the economic basis is addressed, interventions will be limited. Economic arguments are what gets attention, rather than promoting well-being through the lens of altruism.

The demands on healthcare providers increase every year, Kowalski observed. Given that, she asked what could be studied further to mitigate the increased burden. Adibe responded that on a simple level, he urged leaders to listen to providers. Leaders are now making decisions with insufficient information. They need to know the trade-offs. For example, what does reducing administrative support do for turnover for physicians and nurses? What is important to the providers? He joked that a rallying cry should be “No more yoga!” (signifying a simple fix to a larger problem). Looking at the data from doctors and nurses, a study in JAMA ranked operational drivers like improved workflows and more autonomy in the clinic as more critical than wellness efforts (Aiken et al., 2023). Leaders need better metrics like this to make more informed decisions, he said.

Day underscored the problem with cosmetic approaches, such as offering apples in the cafeteria, while toxic bosses and ineffective processes persist. However, the challenge is finding the balance between changing systems and the smaller changes that Christina Maslach and Tait Shanafelt discussed that can snowball (see Chapter 2). If too much is done for individuals, bigger things are ignored until a crisis. She is a proponent of looking at what is possible within an organization but is tired of having to make the argument about cost and return on investment. “I would like to say ‘Stop hurting people as an organization.’ We have to hold organizations accountable,” she stated. Burnout should not be a “cost of doing business.” The challenge is to create a more efficient system and work environment where people are not getting sick. Referring to civility and efficiency, Kowalski commented on the physical layout of workplaces as a topic to study, such as the effect of the role of the physicians’ cafeteria in increasing communications through “casual collisions.” She wondered about other opportunities to think differently and creatively. Adibe expanded on the role of the built environment on well-being. In healthcare settings, for example, it has been

___________________

2 For more on RVUs, see https://www.cms.gov/cms-guide-medical-technology-companies-and-other-interested-parties/payment/physician-fee-schedule.

documented that the view from a hospital room affects patient outcomes. It is important to understand the optimal healing environment. Day added that remote work also highlighted that isolation can be detrimental to well-being, problem-solving, and culture.

OPEN DISCUSSION

Referring to Day’s comment about the need for a fit between an individual and an organization, a participant queried whether that blames the individual for any problems. Day said it is not a blame situation, but individuals must have the right training to maximize their capabilities. A mismatch of expectations might also occur, for example, when individuals say the workload is too heavy, but the system has set that amount of work as the target, a participant observed. Day suggested this is where participation comes in. A job analysis can show what is required and get people to talk about requirements and expectations.

Organizations in the midst of budget tightening have to deal with people, space, and data components, a participant commented. Adibe noted the overall state of the health system is reactive. Value-based care does not solve everything, but it is a proactive approach to patient care that may help ameliorate many challenges.3 A compounding factor of burnout for many physicians is when their patients cannot get needed care and resources, which contributes to the physicians’ sense of moral injury and defeat. A broader transition toward a more preventive healthcare system and support of social challenges outside the hospital is key.

Day noted that improvement requires more than just collecting data. It must be shared to get organizations and leaders to buy in. Another participant shared her experience implementing interventions. She noted there is often a different language between the people who work in the field of organizational development and related issues and the people who are working in the organizations themselves. She finds it effective to frame the issue through an enterprise risk lens, she said. She reminds leaders of tiers of risk, encompassing not only economic but also human, reputational, and management risks. Once embedded, workplace culture is part of an enterprise’s risk dashboard. Leaders need adequate information, Adibe agreed. A big challenge is that well-being and burnout have been considered separately

___________________

3 For more information from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services on value-based care, see https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/key-concepts/value-based-care.

from other enterprise factors. An enterprise risk dashboard or other tools such as a well-being dashboard4 he and his colleagues are developing that considers both economic and human factors may move it to more operational considerations and as part of all that an enterprise is doing. Day suggested that costs and return on investment can be part of the framing of risk, such as related to absenteeism and turnover. For example, a poor reputation affects employee recruitment, insurance, and other costs. She called for both a theoretical moral high ground and pragmatic considerations to get things done. A classic tenet is that attitudes need to change before behavior does, but maybe behavior change can lead to attitude change, she posited.

Kowalski suggested that well-being must be embraced as part of the fiber of the organization at the same level of professionalism, safety, and other aspects of quality. Adibe said one challenge of promoting wellness is the dearth of quality research. While a systematic review of well-being initiatives found that individual-focused interventions had little to no effect, the quality of studies was in general poor, which contributes to a lack of direction on how best to support physician well-being (Haslam et al., 2024). Philosophically, well-being is seen as an add-on or footnote, while other issues are prioritized. COVID-19 helped to change that, when widespread resignations placed enterprises at risk. If leaders do not have the tools to codify the risks, they will not find appropriate solutions. He called for better transparency around costs. Wellness must be at the “big table,” Day said. She noted some organizations put the concept in their mission, vision, or policies but do not act on it, which she called “wellness washing.” Clients and patients are always placed first, but British entrepreneur Richard Branson has advocated to put employees first and they will treat the customers well.

___________________

4 For more information on well-being dashboards, see https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.22.0219.