Impact of Burnout on the STEMM Workforce: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 4 Consequences of Burnout and Measurement Challenges

4

Consequences of Burnout and Measurement Challenges

Highlights from the Presentations

- Individual-level and occupational-level consequences of burnout have been well and sufficiently documented with enough data to implement and test interventions (Lai).

- Early-career STEMM workers are particularly vulnerable to burnout but there is relatively less on gender differences and especially on racial differences in burnout implications (Lai).

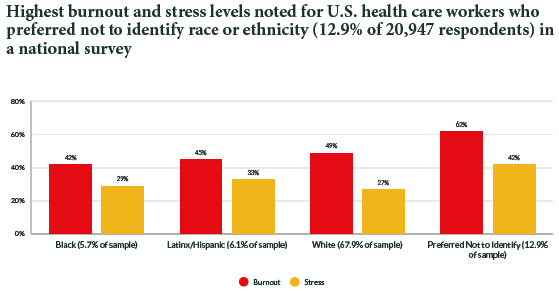

- One study reported particularly high burnout and stress among respondents who chose not to identify by race or ethnic group, which merits further exploration to understand how individuals of various racial identities choose to report or not report burnout (Lai).

- There is a need for more research on gender and racialized consequences of burnout for organizations, such as potential implications of uneven turnover. There is also a need for research on leader burnout and spillover effects of this (Lai).

- Besides looking at what is not working or who is experiencing burnout, it is valuable to look at the places where things are working or those individuals who are not experiencing burnout (Porta).

- Accountability is important, but care must be taken in determining what to measure to avoid unintended consequences (Lai, Porta).

Planning committee member José Pagán (New York University) moderated the next workshop session on the consequences of burnout in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM). Alden Lai (New York University) shared key observations derived from the commissioned paper he undertook with colleagues. (For the full text of the paper, see Appendix C). Carolyn Porta (University of Minnesota) served as discussant followed by general discussion with in-person and virtual attendees.

The paper at the heart of this panel was commissioned to examine the impact of burnout for individuals and organizations and how this might vary by key demographics such as gender and race. The paper and presentation also provided insight into areas where scientific knowledge of burnout, particularly along lines of gender and race, is still lacking.

REVIEWING CURRENT KNOWLEDGE TO SUGGEST FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Lai began by introducing the methodology of the literature review he conducted along with co-authors Mark Linzer, Amber Stephenson, Erin Sullivan, and Kenneth Wee. He explained that they took a review-of-reviews approach, a search for non-reviewed articles, and a backward and forward reference search to find the set of relevant scientific knowledge on the consequences of burnout in STEMM fields. He concurred with previous speakers that based on this review, “We have enough data to act.” Ultimately, he argued that doing more studies to identify consequences would be less helpful than studies to chart new areas of inquiry.

Researchers have captured a sufficient breadth of individual- and occupational-level consequences of burnout, although most are in medicine and other healthcare settings with less in other areas of STEMM. The individual-level consequences can be categorized into somatized symptoms, poorer quality of life, physical and mental health conditions, poorer cognitive function, substance use, and suicide ideation, with a range of manifestations (see Table 4-1).

TABLE 4-1 Individual-Level Consequences of Burnout

| Categories | Manifestations |

|---|---|

| Somatized symptoms | Headaches, neck pain, body pain |

| Poorer Quality of Life | Loss in appetite, loss in sleep, chronic fatigue |

| Physical health conditions | Gastrointestinal infections, respiratory infections |

| Mental health conditions | Anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, mood disturbances |

| Poorer Cognitive function | Poorer prospective memory, delayed memory |

| Substance use* | Alcohol use, medication use |

| Suicide ideation | Suicide ideation |

* Indicates mixed evidence, in part due to inconsistency in measurement tools.

SOURCE: Alden Lai, Workshop Presentation, October 1, 2024.

Occupational-level consequences include talent loss, poorer work performance, poorer employee well-being, and less talent growth (see Table 4-2).

Lai noted that the studies reviewed show that early-career STEMM workers are particularly vulnerable to burnout (e.g., Laschinger et al., 2015; Rudman and Gustavsson, 2012). For example, one study found that employees with 1 to 3 years of experience were most likely to leave, compared with those with fewer than 6 months or more than 5 years (Trinkenreich et al., 2024). It is important to be sensitive to those workers, Lai said.

TABLE 4-2 Occupational-Level Consequences of Burnout

| Categories | Manifestations |

|---|---|

| Talent loss | Intention to leave training programs, job, or profession |

| Poorer work performance | Absenteeism, reduced ability to work, less professionalism |

| Poorer employee wellbeing | Lower job satisfaction, regretting career choice |

| Less talent growth | Reduced engagement in professional development activities |

SOURCE: Alden Lai, Workshop Presentation, October 1, 2024.

Occupations, work responsibilities, and work settings drive some of the differences in the consequences of burnout, Lai continued. For example, nurses had higher burnout and reported more changes in their workload during the pandemic than did physicians (Peck and Porter, 2022). Those with direct involvement in treating patients are at higher risk for burnout (Mukherjee et al., 2022), and work settings such as emergency medicine and intensive care also affect the consequences of burnout (Hodkinson et al., 2022). In this way, the contexts of care in medicine as well as in the general context of work across other STEMM fields matter for how burnout manifests.

“Even without all the data, we can take meaningful action,” Lai said, echoing Tait Shanafelt’s earlier point that evidence-informed, rather than evidence-based, research can be sufficient. “The time to take action is now.” He underscored the lack of attention within the research to pronounced gender differences in burnout and urged implementation and testing of interventions. Drawing for existing evidence, women report higher burnout than men and a higher rate of intention to leave their jobs (Apple et al., 2023). Another study found that female neurologists were more likely to report suicide ideation than male neurologists (LaFaver et al., 2018).

Lai argued it was also very important to understand burnout and race. Specifically, he noted, “We need to better understand how persons of color choose to report burnout, as well as their lived experiences in the context of burnout.” To this point, Lai shared data on levels of burnout reported by Black, White, and Latinx healthcare workers as well as healthcare workers who did not share their racial identity (Prasad et al., 2021). Almost 13 percent of the respondents chose not to identify their race or ethnicity. This group ultimately reported the highest rates of burnout and stress: 62 percent reported burnout and 42 percent reported stress (see Figure 4-1). This raises the question of who the people are who prefer not to identify and why and what barriers this might pose to our understanding of racialized implications of burnout.

Another area where Lai argued more research is needed is to link the mechanisms between worker burnout and organizational and societal consequences, such as the domino effect in which leaders’ burnout has detrimental effects on their direct reports and the consequences of absenteeism and attrition. Other future work might include measurement issues related to subjective and objective measures to develop a more cohesive call to action; organizational and social contexts in which human capital is being eroded or lost (thus upending careers and losing out on innovation); and translating knowledge into action for workers, employers, and institutions.

SOURCE: Alden Lai, based on Prasad et al. (2021), Workshop Presentation, October 1, 2024.

REFLECTIONS

Porta is a nurse-scientist involved in workforce and public health, as well as a forensic nurse, an area with high turnover and experience with trauma. She offered two personal examples in which family members made choices based on the work environment about whether to stay or leave their jobs to ground her remarks. An uncle retired in 2022 but returned to the workplace as a consultant. In contrast, Porta’s daughter left a job where she felt objectified, and her manager did nothing to support her.

Most of the time people spend during the day is at work, and she expressed concern that the state of workforce science lags other sciences. The budget of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health is small compared with other research agencies. They are the healers charged with keeping society healthy, yet they have limited capacity to understand and improve workplace conditions. Porta commented on the disconnect between burnout and big data and called for more sophisticated tools to understand and predict burnout to prevent it. Sensors are used for all kinds of things, from vehicle tires to animal health, she commented, and real-time data collection, artificial intelligence, and predictive analytics may be useful in workforce well-being.

Porta also suggested looking at protective factors and what works. For example, if a study shows a burnout rate of 60 percent, what is going on with the 40 percent who do not experience burnout, she posed. It is also important to look at thriving workforce members and their workplaces.

The paper developed by Lai and colleagues is a good place to start, she concluded.

Pagán asked about the broader impact of the consequences in the studies identified by Lai. He responded that many of the studies reviewed pointed to the financial effects, such as an estimate that turnover costs $4.6 billion annually (Han et al., 2019). While they should be taken in account, he noted that the individual- and organizational-level consequences that surfaced are not captured by the numbers alone. Only a few studies have looked at the societal level. He noted that one study suggested more opioid prescriptions are given to patients when physicians are experiencing higher burnout.

Porta added that the costs of not retaining workers and of onboarding new workers are well known. Less well known are the costs of other factors. For example, she asked, how do we quantify and demonstrate the effect of inaction versus action in addressing workplace well-being. Pagán agreed that the information is hard to capture and asked why more organizations do not attempt to do so. Porta posited that many react to day-to-day operations and do not take the time to step back despite the importance. She has stayed with her organization because of the team, supervision, and organizational values, but a neighboring health system has a high turnover. It is important to find the space to look at why and seek transformational excellence.

Lai referred to Cha’s comments about workplaces in which family-friendly policies are widely used (see Chapter 3). Research by the Oxford Wellbeing Research Centre has shown that employee well-being improves firms’ performances, and the top 100 in terms of well-being outperform the Standard and Poor (S&P) index.1 Another immense challenge is that burnout can result from system failure and inefficiency. He agreed that unit-level action can be undertaken, and perhaps other pockets of opportunity can be identified.

OPEN DISCUSSION

During audience questions, a participant commented that healthcare organizations are accountable for many measures but are generally not accountable for workforce well-being and some upstream factors, such as workload, measured through self-reports or another type of measurement that were being implemented by healthcare organizations to address this. Lai said his review did not find research engaging directly with the ways

___________________

1 For more information, see https://wellbeing.hmc.ox.ac.uk/.

in which to use burnout measures as tools of accountability. He reminded the group that the Maslach Inventory (see Chapter 2) is intended as a discovery tool, not a diagnostic tool. He added that the Oxford Centre convinced S&P Global to include questions related to job satisfaction, stress, happiness, and other measures when reporting on corporate sustainability, although he does not see this happening widely in the healthcare space. Now might be the time to consider it, he urged. Porta offered lessons learned from Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulations: regulations incentivize industry to engineer out risk. When an entity is self-driven to protect itself, people are sometimes disincentivized to report a mental or emotional health need. Federal policies are important, but organizations must take the initiative to examine what is happening internally, especially if they are losing workers.

Echoing previous comments, a participant noted that the business case is well established to prevent burnout but does not lead to change. Measurements alone do not work, but retention as a metric may work. Porta said underreporting is a significant issue, which is why other ways of knowing beyond measurements are needed. One participant noted that those who are leaving are the very people who might otherwise advocate for more work-life balance if they stayed. Porta said that when people leave, an organization is losing creativity and the next big idea, and it must decide whether to transform. She pointed to an annual letter that finance leader Ross Stevens sends to stakeholders, in which he says his company is tough on ideas but kind to people.

Tait Shanafelt pointed to an important dimension related to accountability: If the wrong outcome is measured, it can foster gaming and underreporting and worsen the situation. In addition, less-resourced healthcare systems could be disadvantaged if the wrong metrics are focused upon. He suggested looking at a study under way by The Joint Commission2 as well as a piece by John Ripp and himself (Ripp and Shanafelt, 2024) about how to hold hospitals accountable for clinicians’ well-being. It is important to hold each other accountable, Porta agreed. “Team member, ally, accomplice—all have a role to play,” she said. Lai also called for internal accountability within a healthcare system to learn why some units are performing differently regarding burnout. Accountability can catch the

___________________

2 For more information, see https://www.jointcommission.org/our-priorities/workforce-safety-and-well-being/resource-center/worker-well-being/.

“bad apples” but also identify those with good intentions that need help in achieving the best outcomes.

Commenting on the role of leaders and training to effect change, Porta stressed the importance of an employee’s immediate supervisor, which she said is backed up in the literature and her own experience. She noted some health systems base part of leaders’ bonuses on their workers’ well-being, but leaders must be prepared for this role through support and mentorship.