Newborn Screening in the United States: A Vision for Sustaining and Advancing Excellence (2025)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

Newborn screening (NBS) programs in the United States provide a public health service available to all infants regardless of geographic, ethnic, or socioeconomic differences (Boyle et al., 2014; CDC, 2011). State- and territorial-run NBS public health programs identify babies at risk of serious but treatable conditions, and connect them to follow-up care with the goal of providing the best chance at a healthy life (HRSA, 2023a). Public health newborn screening encompasses dried blood spot, hearing loss, and congenital heart defect testing. Hearing loss and congenital heart defect screening are often referred to as point-of-care testing because these tests are both administered and interpreted at the site of clinical care for the newborn, rather than in a laboratory. Dried blood spot screening, on the other hand, involves collection at the point of clinical care but testing in a designated laboratory (Kemper et al., 2012). This report is focused on U.S. public health newborn screening using dried blood spots.

As a population health initiative, nearly every infant in the United States is screened at birth—by collecting blood from the baby’s heel on a special card, typically within the first 24–48 hours—and a small proportion of babies will be identified as at risk for a condition that benefits from early medical intervention (CDC, 2012; HRSA, 2023b). States and territories have authority over the policies and operations of NBS programs within their jurisdictions, while the federal government provides national guidance and some support and coordination. Although each state or territory independently determines what conditions their program will screen, a recommended set of conditions is provided by the

secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) with the support of a federal advisory committee. Ultimately, states and territories choose which conditions to screen to address the needs of their populations and comply with factors such as legislative requirements, budgets, workforce availability, technological resources, and the influence of advocacy (Grosse et al., 2016). Among those in public health, newborn screening is considered a great achievement based on its identification of infants with serious, urgent conditions who can receive life-saving treatment and intervention (CDC, 2011).

NBS programs provide a public health service to infants that extends beyond the screening test. Public health professionals play key roles in informing and educating parents of affected newborns and connecting these infants with confirmatory testing and follow-up care in the health care system. Further, NBS programs work with partners in a larger ecosystem that supports identification, follow-up, and treatment of babies. These partners include regulatory agencies, researchers, care providers, payors, advocacy groups, patients, and parents, among others.

HISTORY OF NEWBORN SCREENING

Early Roots in Advocacy

Public health newborn screening was built on a bedrock of advocacy and personal experience, with no clearer example than Robert Guthrie himself—whose work in the 1960s provided the scientific basis for newborn screening. As the father and uncle of children with intellectual disabilities, Guthrie applied his expertise as a medical microbiologist studying cancer toward developing an inexpensive bacterial inhibition assay that allowed for early detection of phenylketonuria (PKU) in newborns (Levy, 2021). PKU is a rare disorder in which buildup of the amino acid phenylalanine leads to brain damage and intellectual disability; early reports suggested that a low phenylalanine diet prevented intellectual disability in children with PKU (Bickel et al., 1953; NHGRI, 2014). The knowledge that intellectual disability from PKU could be prevented hit close to home for Guthrie, whose niece was diagnosed with the rare condition, influencing him to envision universal PKU screening. As a result, the concept of newborn screening was born—with the initial goal of population screening to identify infants at risk of PKU and connect them with prompt diagnosis and treatment (Levy, 2021).

Mandated screening for PKU, performed without parental consent, quickly became widespread, despite calls for further research on the disease pathology, test validity, and treatment outcomes and more cautious

implementation (AAP, 1967; Paul, 1998; Rule, 1965). Ultimately, PKU screening prevented intellectual disability for many infants identified with PKU who received treatment; however, there were several unintended consequences including malnutrition for infants with PKU with inappropriate diet management, PKU anxiety syndrome,1 and the phenomenon of maternal PKU (Brosco et al., 2008; Lenke and Levy, 1980; Paul and Brosco, 2013; Rothenberg and Sills, 1968).2

Tandem Mass Spectrometry and the Expansion of Newborn Screening

Following PKU screening, researchers began developing and implementing tests for other conditions (Watson et al., 2022). For decades, the number of conditions that could be screened was limited by the amount of blood available for testing. However, the application of tandem mass spectrometry to newborn screening in the 1990s opened the door to screening for exponentially more conditions. Using this biochemical technology, the levels and patterns of numerous metabolites can be analyzed from a single dried blood spot, enabling more accurate detection of risk for more conditions than previously possible (Chace et al., 2003). Tandem mass spectrometry was incorporated into public health newborn screening by some programs, leading to an increase in both the number of disorders screened and variability across NBS programs in the United States (Tarini, 2007; Tarini et al., 2006).

American Federalism and the Creation of Federal Guidance on Public Health Newborn Screening

State and territorial health policy decisions, including those for public health newborn screening, are made in the context of American federalism—the division of power and responsibilities between national and state roles (Turnock and Atchison, 2002). The relationship between state and federal roles in public health newborn screening has evolved over time. Under the U.S. system, states and territories establish health care practice standards unless Congress determines a significant national

___________________

1 In the 1960s, PKU anxiety syndrome was used to describe parents presenting with acute and chronic anxiety after their child received a false-positive screening result. These parents “persisted in their belief” that their infants may have intellectual delays “despite repeat [PKU] negative tests and considerable reassurance and support from physicians” (Rothenberg and Sills, 1968).

2 Maternal PKU occurs when a pregnant woman with PKU does not have appropriate diet management before and during pregnancy. High levels of phenylalanine in the mother’s blood can harm the developing baby and lead to intellectual disability, behavioral problems, and seizures in the baby (Lenke and Levy, 1980; Paul and Brosco, 2013).

policy warrants preemption of these standards (Kraszewski et al., 2006). From the inception of public health newborn screening, states and territories have had the authority to establish and implement NBS programs with the earliest statutes enacted in the 1960s (Levy, 2021). For nearly four decades, state and territorial laws on newborn screening were developed, and this decentralized approach led to variation in policies and practices for NBS programs across the United States.

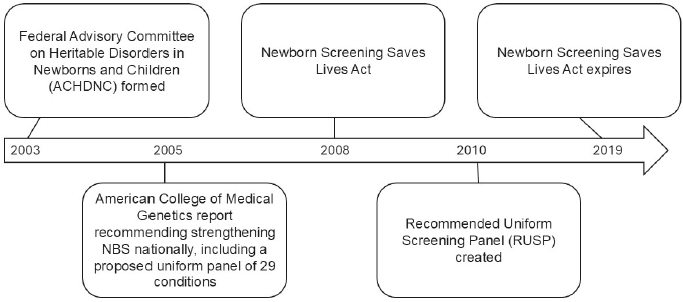

In the early 2000s, several actions were taken at the federal level to address the variability across state and territorial programs that had developed in the absence of national guidance (HRSA, 2021). First, the federal Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children (ACHDNC) was formed in 2003 as a provision of the Public Health Service Act to advise the secretary of HHS about newborn and childhood screening.3 Then, in 2005, the American College of Medical Genetics released a report commissioned by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) with recommendations to strengthen newborn screening nationally, including a proposed uniform panel of 29 conditions (ACMG Newborn Screening Expert Group, 2006). This report laid the foundation for the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP), a list of disorders that the secretary of HHS recommends be included as part of every NBS program—established in 2010 (HRSA, 2021).

The Newborn Screening Saves Lives Act was enacted in 2008 to expand federal support for state and territorial NBS programs and develop national guidance, including requiring ACHDNC to make recommendations on conditions for newborn screening. This legislation, which was reauthorized in 2014, expired on September 30, 2019 (Figure 1-1). Since then, attempts to reauthorize, and thereby reinstate, grant programs and other initiatives to support newborn screening, have been unsuccessful, at least in part due to concerns about the retention and reuse of newborn dried blood spots without informed consent (Sterman and Molina, 2023). Despite this, ACHDNC continues to operate as a discretionary committee and advise the secretary concerning conditions to include on the RUSP and improvements to public health NBS delivery (HRSA, 2021).

States and territories continue to have authority over the policy and practice of NBS programs in their jurisdiction, whereas the federal government provides support for state and territorial programs, offers national guidance—such as the RUSP, and coordinates some cross-state activities. Some states have also instituted RUSP alignment laws, which require a state’s NBS program to screen for conditions added to the RUSP within a certain time frame (EveryLife Foundation for Rare Diseases, n.d.).

___________________

3 Section 1111 of the Public Health Service Act, 42 U.S.C. 300B-10.

NOTE: NBS = newborn screening.

The federal guidance provided by the RUSP thus plays a greater role in such states than in those that use other processes to establish their set of screened conditions. Overall, this combination of state and territorial-based approaches with federal guidance and support allows states and territories to consider the needs of their population and their available resources but can produce variation in the ability of NBS programs to achieve and maintain excellence.

CONCEPTS UNDERPINNING PUBLIC HEALTH NEWBORN SCREENING

Principles for Population-Based Screening

Early NBS programs were heavily influenced by a 1968 report published by the World Health Organization titled the Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease, which recommends 10 principles, commonly known as the Wilson and Jungner principles, to guide screening for chronic conditions (Crowe, 2008; Wilson and Jungner, 1968). When applied to newborn screening, these principles have influenced inclusion of conditions based on the criteria of severity, urgency, and treatability—and with an emphasis on direct benefits to the child (Crowe, 2008). This report also discussed characteristics that screening tests should have to be employed at a population level (i.e., validity, reliability, yield, and cost). Wilson and Jungner proposed that tests should accurately, reliably, and efficiently identify individuals who have a condition and those who do not with high sensitivity and specificity, and they should do so relatively cheaply (Wilson and Jungner, 1968). These principles continue to guide the delivery of public health newborn screening and choices

concerning which conditions should be added to screening, although there are pushes to expand programs to include both conditions and screening technologies that may not fulfill these criteria (Currier, 2022; King et al., 2021).

Many jurisdictions in the United States operate public health newborn screening without a requirement for formal informed consent, meaning that parents do not have to give permission but may opt out for religious or other reasons (King and Smith, 2016).4 Although parents are generally permitted to refuse screening, many may not be aware of public health newborn screening or that they have the right to refuse (Rothwell et al., 2010). Different aspects of governmental authority are referenced when discussing nonconsented public health newborn screening, including the concept of parens patriae in which states have a role in defending the interests of those who are unable to protect themselves, including assuming parental rights to protect a child’s health and welfare when the parents are unable or unwilling to do so (Gostin, 2000; King and Smith, 2016). The ethical justification for nonconsented public health newborn screening was first articulated by Faden, Holtzman, and Chwalow. In their paper, the authors argue that PKU screening has a clear net benefit and parental refusal poses a serious, if unlikely, risk of harm to the baby; therefore, a lack of explicit consent is appropriate in this specific circumstance (Faden et al., 1982). Although not necessarily the authors’ original intent, the justification for nonconsented screening for PKU has been extended as other conditions have been added to public health newborn screening based on the criteria of urgency, severity, and treatability (Currier, 2022; Faden et al., 1982). Bioethical frameworks and principles underpinning public health newborn screening are explored further in Chapter 3.

Documenting the Public Health Achievements of Newborn Screening

As reflected in Box 1-1, those involved with and affected by newborn screening in the United States attribute several important successes to these programs. However, demonstrating the impact of newborn screening at a national level and its benefit to the public is complicated by limited coordinated data collection efforts for screening, short-term follow-up, and longitudinal monitoring of health outcomes (Watson et al., 2022). For example, it is difficult to draw clear lines between receipt of newborn screening and metrics of long-term benefits or cost savings at the population level from available data, although some evidence is

___________________

4 Consent and opt-out requirements vary across the 56 state and territorial NBS programs. These practices are discussed further in Chapter 2 and more information about individual programs can be found at https://www.newsteps.org/data-center/state-profiles (accessed January 30, 2025).

BOX 1-1

Newborn Screening in the United States

Newborn screening is considered an achievement by those involved in public health (CDC, 2011), but quantitatively documenting its successes can be difficult. Nevertheless, there are several features that indicate the value of newborn screening and the tremendous investment that has been made to identify infants at risk of serious, congenital conditions.

- All infants born in the United States have access to newborn screening.

- Of the ~3.6 million infants born annually, approximately 98 percent receive newborn screening (CDC, 2012; NCHS, 2024).

- Approximately 7,000 infants are identified with a disorder annually via dried blood spot screening (~20 per 10,000 infants) (Gaviglio et al., 2023).

- The United States provides global leadership in quality and accuracy of newborn screening through CDC’s Newborn Screening Quality Assurance Program (NSQAP), which offers quality assurance services to more than 670 laboratories worldwide, including all laboratories in the United States, laboratories in more than 86 countries, and 32 NBS test manufacturers (CDC, 2024b).

- The United States has led technology and assay development for newborn screening, including the incorporation of tandem mass spectrometry and molecular methods (Furnier et al., 2020; Therell and Adams, 2007; Watson et al., 2022).

available for a subset of conditions (Grosse, 2015; Van Vliet and Grosse, 2021). Even the most recent national statistic on the percentage of infants screened annually (over 98 percent) was published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2012—more than a decade prior to the publication of this report (CDC, 2012), although more recent statistics are available for birth prevalence (Gaviglio et al., 2023). Instead, these NBS achievements are most often illustrated through individual stories (APHL, 2013).

EMERGING TENSIONS IN PUBLIC HEALTH NEWBORN SCREENING

This report envisions a path forward to navigate the mounting tensions, challenges, and pressures facing newborn screening in the United States, while preserving and strengthening what is already considered a public health achievement. Tensions arise in public health newborn screening between population health needs and individual autonomy, challenging the ability of the system to address these often-competing priorities (Bayefsky et al., 2015). Public health NBS programs, for example, must balance their mandate to screen all newborns with the individual

needs and rights of each child and their family, including rising concerns about data privacy, as well as wavering trust (Grant, 2022). Public health newborn screening must also contend with opportunities and challenges posed by transformative therapies and genomic sequencing, which open the door to expanding the conditions screened within an already resource-constrained environment (Andrews et al., 2022; CDC, 2012; GAO, 2016). The process for adding conditions to the RUSP ensures a rigorous evaluation of evidence but struggles to keep pace with medical advances and places a burden on advocacy communities and others (Andrews et al., 2022; Bailey et al., 2021; Kemper et al., 2014). Furthermore, well-resourced advocacy communities are better positioned to engage in research and advocate for inclusion of their condition on the RUSP and state panels, whereas conditions with less funding and advocacy support face challenges gaining recognition and prioritization (Halley et al., 2022; Largent and Pearson, 2012). These tensions are often highest among those deeply interested in or affected by newborn screening. If unaddressed, the tensions, challenges, and pressures described, among others, may imperil this public health service (Currier, 2022; McCandless and Wright, 2020).

Ongoing Efforts by Partners in the NBS Ecosystem5

Partners across the NBS ecosystem recognize these complex, ongoing challenges and are taking actions to address them. Reflecting the scope of public health newborn screening, partners involved in these activities include federal agencies, state and territorial public health departments, researchers, professional societies and consortia, advocacy groups, individuals, and others. To strengthen NBS programs and harmonize across states and territories, the Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL) entered a cooperative agreement in 2012 with the Genetic Services Branch of HRSA to coordinate the Newborn Screening Technical assistance and Evaluation Program (NewSTEPs), which provides quality improvement tools, an innovative data repository, and technical resources (Ojodu et al., 2017). APHL has received new funding from HRSA through a cooperative agreement titled National Center for Newborn Screening System Excellence (NBS Excel).6 Initial steps have also been taken by different partners to build a more robust data infrastructure, including the NewSTEPs data repository for programmatic data, quality indicators, and short-term follow-up data, established in 2013, and then more recently, CDC’s creation

___________________

5 The report focuses on critical functions and actions to strengthen public health newborn screening for the future; descriptions of the roles and structures of federal and nonfederal activities relevant to newborn screening are current as of March 24, 2025.

6 See the NBS Excel and NBS Propel notice of funding opportunity, https://www.hrsa.gov/grants/find-funding/HRSA-23-077 (accessed February 3, 2025).

in 2021 of a national laboratory data platform, Enhancing Data-driven Disease Detection in Newborns (ED3N) (CDC, 2024a; Ojodu et al., 2017).

HRSA launched a series of grants in 2023 to fund activities to improve and expand the NBS system, address timely collection and reporting of NBS specimens to improve early diagnosis and treatment for individuals with heritable conditions, improve short-term follow-up through long-term follow-up, and help families understand and navigate the process from confirmation of a diagnosis to treatment (HRSA, 2024).7 In lieu of passing the NBS Saves Lives Act, Congress increased funding for CDC’s NSQAP and HRSA’s Heritable Disorders Program.8 Rare disease patients, their families, and advocacy groups, such as the National Organization for Rare Disorders, EveryLife Foundation for Rare Diseases, and Expecting Health, have created influential resources (e.g., Newborn Screening State Report Card and the Newborn Screening Family Education Program) to help reduce gaps in the NBS ecosystem, built nomination packages, developed disease-specific registries to inform research, and raised their voices for changes to better support the needs of their communities (Andrews et al., 2022; Expecting Health, 2024).

A vision forward could help foster and integrate these parallel efforts and address challenges to public health newborn screening that still loom on the horizon. To build upon these ongoing efforts, Congress included a mandate in the 2023 appropriations process for a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine study “to examine the current status of Newborn Screening systems, processes, and research and make recommendations for future improvements.”9

STUDY SCOPE AND APPROACH

In recognition of these challenges and to help inform the future of U.S. newborn screening, the Office on Women’s Health in the Department of Health and Human Services asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine to convene an ad hoc committee of experts to provide short-term options to strengthen existing NBS programs and a vision for the future. The committee’s statement of task is presented in Box 1-2.

___________________

7 See the NBS Excel and NBS Propel notice of funding opportunity, https://www.hrsa.gov/grants/find-funding/HRSA-23-077 (accessed February 3, 2025), and the NBS Co-Propel notice of funding opportunity, https://www.grants.gov/search-results-detail/349438 (accessed February 3, 2025).

8 Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023, Public Law 117-328, 117th Congress (December 28, 2022); House of Representatives Report No. 117-403 (2022).

9 Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023, Public Law 117-328, 117th Congress (December 28, 2022); House of Representatives Report No. 117-403 (2022).

BOX 1-2

Statement of Task

An ad hoc committee of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine will examine the current landscape of newborn screening (NBS) systems, processes, and research in the United States. The committee will make recommendations for future improvements that help modernize newborn screening to be adaptable, flexible, coordinated, communicative, capable of efficient and sustainable adoption of screening for new conditions using new technologies, and a public health program from which all infants benefit. The committee’s work will focus on the following tasks:

- Examine state and federal capacities to strengthen current screening processes and implement screening for new conditions, including considerations for future conditions added to the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP).

- Review existing and emerging technologies that would permit screening for new categories of conditions and describe

- how these new technologies may impact states;

- changes to public health infrastructure needed to incorporate new technologies while upholding and implementing the required components of newborn screening;

- options for incorporating new technologies to allow for screening of additional conditions; and

- research, technological, and infrastructure needs to improve diagnosis, follow-up, and public health surveillance.

- Review NBS data collection processes for tracking disease prevalence, improving health outcomes, conducting longitudinal follow-up, defining the natural history of conditions that can be screened for, and measuring quality of life.

- Examine the RUSP review and recommendation processes, including the process of selecting new conditions that could be added to the RUSP; conducting review of the evidence to support adding new conditions; scaling up these review and recommendation processes to efficiently handle the review of potentially hundreds of conditions; and considering whether additional factors should be included in the analysis of harms and benefits (e.g., societal harms such as financial cost or opportunity costs, and family benefits such as avoiding the “diagnostic odyssey”).

The committee’s final report will describe (a) short-term options that could be implemented at the state and/or federal level over the next 2 to 3 years to help strengthen existing NBS programs and address the current challenges facing state programs, and (b) a vision for the future of NBS and a road map for how to implement and achieve that vision over the next 5 to 15 years. The report will include options for how to implement longitudinal follow-up data collection to improve understanding of the impact of NBS on infant health outcomes (including morbidity and mortality, and quality of life for screen-positive infants). The committee will consider the resources required for implementation, such as changes to the current NBS system that will need to occur; the feasibility of implementing the future vision; and the challenges and barriers that may arise when trying to implement the road map.

The committee’s charge focuses on newborn screening through blood spot testing. During the newborn period, babies receive other types of testing, including hearing screening and pulse oximetry screening for potential heart disease; these other forms of newborn assessment were out of scope for this study. Similarly, the study focuses on the NBS program as implemented in the United States, and the strategies set forth in this report are targeted to partners within the U.S. NBS ecosystem. The United States has long been at the forefront of newborn screening, influencing and supporting initiatives and programs worldwide (APHL, 2013; CDC, 2024b). Therefore, this report’s guidance may also help inform other countries and international bodies including the World Health Organization and the International Society for Neonatal Screening as they encounter challenges and opportunities similar to the ones this study addresses.

Committee’s Interpretation of the Charge

Although the statement of task asks for both near-term operational solutions and a long-term vision for the future, the committee quickly realized that no single study could fully attend to both duties with the given scope and time line. A number of partners supporting public health newborn screening, including such federal agencies as HRSA and CDC, are actively working to address more immediate problems within the existing framework. With the encouragement of these partners, the committee prioritized its efforts toward developing a longer-term vision for building a more modern, sustainable, and adaptable NBS ecosystem and a road map to accomplish this vision after first reviewing and examining the current state and ongoing efforts to address challenges in public health newborn screening.

A future for public health newborn screening in which all infants can benefit needs to be grounded in clear goals and ethical principles. Public health newborn screening plays an important role in detecting disease and connecting affected infants and families to the clinical care system to improve health outcomes. However, disparities in access and quality can affect babies’ and families’ experience of public health and health care systems and affect these outcomes. The report focuses on recommendations to strengthen the excellence and support the quality of public health newborn screening, while recognizing that systemic issues in the larger U.S. clinical care system are likely to present ongoing and important areas of work but are outside of this study’s scope.

Study Approach

Reflecting the complexity of its task, the committee included 14 members with expertise in public health newborn screening, state and federal public health, lived and parental experience, bioethical and

legal issues, existing and emerging screening technologies, health systems, health economics, and clinical care disciplines. The committee met multiple times over the course of the study for public virtual and hybrid workshop sessions with speakers who generously shared their research, evidence-based observations, expertise, and experiences with the committee, as well as in committee and working group discussions to analyze the available evidence and develop the conclusions and recommendations presented in this report. See Appendix A for further information on how the committee conducted its work and Appendix B for brief biographies of committee members and staff.

Central to the committee’s approach was soliciting input from individuals interested in or affected by newborn screening in the United States to support ethical decision making; enhance legitimacy, transparency, and justice; and build trust (APHA, 2019). With additional support from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the committee commissioned a team of consultants, together with National Academies staff, to engage with groups and individuals across multiple sectors with lived or professional experience in newborn screening through a series of listening sessions and a virtual questionnaire available in both English and Spanish. More than 600 people participated in these activities, including parents, members of the rare disease community, health care providers, researchers, NBS laboratory and follow-up professionals, public health professionals, payors, industry representatives, privacy advocates, and members of the public.

While responsive to outside needs, concerns, and preferences, the committee recognized that different groups have varied desires and interests and it examined ideas and suggestions in the context of the available scientific evidence. An overview of this engagement process is available in Appendix A with further details on who participated (demographics and sector/group affiliations) and a paper summarizing input is publicly available and titled What We Heard: Engagement Summary on Newborn Screening in the United States.10

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

Following this introduction, Chapter 2 reviews the history and current implementation of public health newborn screening in the United States, including the landscape of partners involved in the broader NBS ecosystem. Chapter 3 discusses the importance of grounding decision making for public health programs such as newborn screening in ethical principles,

___________________

10 Susanna Haas Lyons Engagement Consulting, 2024. Available on the study website at https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/newborn-screening-current-landscape-and-future-directions (accessed October 8, 2024).

concepts, and values. It articulates the approach this report takes to the focus of newborn screening and types of diseases it includes, providing a foundation for analyses and recommendations made in subsequent chapters. Chapter 4 focuses on NBS programs implemented at the state and territorial levels as central actors in achieving the aims of newborn screening, discussing how to support and enhance program excellence. Chapter 5 considers how public health newborn screening can responsibly apply emerging technologies, particularly opportunities and challenges associated with the use of genomic sequencing. Chapter 6 describes the research enterprise relevant to newborn screening. Such research is essential for generating and expanding the evidence base informing public health newborn screening; better understanding and addressing ethical, legal, and social issues; and addressing public health impacts and implementation. Finally, Chapter 7 describes how all parties in the NBS ecosystem can take actions to enable a future vision for newborn screening, through both strategic coordination and optimization of existing processes.

REFERENCES

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics). 1967. Statement on compulsory testing of newborn infants for hereditary metabolic disorders. Pediatrics 39(4):623-624.

ACMG Newborn Screening Expert Group. 2006. Newborn screening: Toward a uniform screening panel and system. Genetics in Medicine 8(Suppl 1):1S-252S.

Andrews, S. M., K. A. Porter, D. B. Bailey, and H. L. Peay. 2022. Preparing newborn screening for the future: A collaborative stakeholder engagement exploring challenges and opportunities to modernizing the newborn screening system. BMC Pediatrics 22(1):90.

APHA (American Public Health Association). 2019. Public health code of ethics. https://www.apha.org/-/media/files/pdf/membergroups/ethics/code_of_ethics.ashx (accessed December 30, 2024).

APHL (Association of Public Health Laboratories). 2013. The newborn screening story: How one simple test changed lives, science, and health in America. https://www.aphl.org/aboutAPHL/publications/Documents/NBS_2013May_The-Newborn-Screening-Story_How-One-Simple-Test-Changed-Lives-Science-and-Health-in-America.pdf (accessed December 30, 2024).

Bailey, D. B., K. A. Porter, S. M. Andrews, M. Raspa, A. Y. Gwaltney, and H. L. Peay. 2021. Expert evaluation of strategies to modernize newborn screening in the United States. JAMA Network Open 4(12):e2140998.

Bayefsky, M. J., K. W. Saylor, and B. E. Berkman. 2015. Parental consent for the use of residual newborn screening bloodspots. JAMA 314(1):21.

Bickel, H., J. Gerrard, and E. Hickmans. 1953. Preliminary communication: Influence of phenylalanine intake on phenylketonuria. Lancet 262(6790):812-813.

Boyle, C. A., J. A. Bocchini, and J. Kelly. 2014. Reflections on 50 years of newborn screening. Pediatrics 133(6):961-963.

Brosco, J. P., L. M. Sanders, M. I. Seider, and A. C. Dunn. 2008. Adverse medical outcomes of early newborn screening programs for phenylketonuria. Pediatrics 122(1):192-197.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2011. Ten great public health achievements - United States, 2001-2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60(19):619-623.

CDC. 2012. CDC grand rounds: Newborn screening and improved outcomes. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 61(21):390-393.

CDC. 2024a. Enhancing data-driven disease detection in newborns. https://www.cdc.gov/newborn-screening/php/about/ed3n-project.html (accessed September 20, 2024).

CDC. 2024b. Newborn screening quality assurance program. https://www.cdc.gov/laboratory-quality-assurance/php/newborn-screening/index.html (accessed July 31, 2024).

Chace, D. H., T. A. Kalas, and E. W. Naylor. 2003. Use of tandem mass spectrometry for multianalyte screening of dried blood specimens from newborns. Clinical Chemistry 49(11):1797-1817.

Crowe, S. 2008. A brief history of newborn screening in the United States. Staff discussusion paper (President’s Council on Bioethics). https://bioethicsarchive.georgetown.edu/pcbe/background/newborn_screening_crowe.html (accessed January 14, 2025).

Currier, R. J. 2022. Newborn screening is on a collision course with public health ethics. International Journal of Neonatal Screening 8(4):51.

EveryLife Foundation for Rare Diseases. n.d. RUSP alignment legislation. https://everylifefoundation.org/newborn-screening-take-action/support-legislation/ (accessed February 21, 2024).

Expecting Health. 2024. The newborn screening family education program: Learn. Connect. Advocate. https://expectinghealth.org/programs/newborn-screening-family-education-program (accessed August 21, 2024).

Faden, R. R., N. A. Holtzman, and A. J. Chwalow. 1982. Parental rights, child welfare, and public health: The case of PKU screening. American Journal of Public Health 72(12): 1396-1400.

Furnier, S. M., M. S. Durkin, and M. W. Baker. 2020. Translating molecular technologies into routine newborn screening practice. International Journal of Neonatal Screening 6(4):80.

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2016. Newborn screening timeliness: Most states had not met screening goals, but some are developing strategies to address barriers. GAO 17-196. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-17-196.pdf (accessed January 10, 2025).

Gaviglio, A., S. McKasson, S. Singh, and J. Ojodu. 2023. Infants with congenital diseases identified through newborn screening—United States, 2018–2020. International Journal of Neonatal Screening 9(2):23.

Gostin, L. O. 2000. Public health law: Power, duty, restraint (vol. 3). Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Grant, C. 2022. Police are using newborn genetic screening to search for suspects, threatening privacy and public health. https://www.aclu.org/news/privacy-technology/police-are-using-newborn-genetic-screening (accessed July 23, 2024).

Grosse, S. 2015. Showing value in newborn screening: Challenges in quantifying the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of early detection of phenylketonuria and cystic fibrosis. Healthcare 3(4):1133-1157.

Grosse, S. D., J. D. Thompson, Y. Ding, and M. Glass. 2016. The use of economic evaluation to inform newborn screening policy decisions: The Washington state experience. Milbank Quarterly 94(2):366-391.

Halley, M. C., H. S. Smith, E. A. Ashley, A. J. Goldenberg, and H. K. Tabor. 2022. A call for an integrated approach to improve efficiency, equity and sustainability in rare disease research in the United States. Nature 54:219-222.

HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration). 2021. History of the ACHDNC. https://www.hrsa.gov/advisory-committees/heritable-disorders/timeline (accessed July 31, 2024).

HRSA. 2023a. About newborn screening. https://newbornscreening.hrsa.gov/about-newborn-screening (accessed July 29, 2024).

HRSA. 2023b. Newborn screening process. https://newbornscreening.hrsa.gov/newborn-screening-process (accessed July 29, 2024).

HRSA. 2024. Cooperative newborn screening system priorities (NBS Co-Propel) program. https://mchb.hrsa.gov/programs/cooperative-newborn-screening-system-priorities (accessed September 26, 2024).

Kemper, A. R., C. A. Kus, R. J. Ostrander, A. M. Comeau, C. A. Boyle, D. Dougherty, M. Y. Mann, J. R. Botkin, and N. S. Green. 2012. A framework for key considerations regarding point-of-care screening of newborns. Genetics in Medicine 14: 951-954.

Kemper, A. R., N. S. Green, N. Calonge, W. K. K. Lam, A. M. Comeau, A. J. Goldenberg, J. Ojodu, L. A. Prosser, S. Tanksley, and J. A. Bocchini, Jr. 2014. Decision-making process for conditions nominated to the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel: Statement of the US Department of Health and Human Services Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children. Genetics in Medicine 16(2):183-187.

King, J. R., L. D. Notarangelo, and L. Hammarström. 2021. An appraisal of the Wilson & Jungner criteria in the context of genomic-based newborn screening for inborn errors of immunity. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 147(2):428-438.

King, J. S., and M. E. Smith. 2016. Whole-genome screening of newborns? The constitutional boundaries of state newborn screening programs. Pediatrics 137(Suppl 1):S8-S15.

Kraszewski, J., T. Burke, and S. Rosenbaum. 2006. Legal issues in newborn screening: Implications for public health practice and policy. Public Health Reports 121(1):92-94.

Largent, E. A., and S. D. Pearson. 2012. Which orphans will find a home? The rule of rescue in resource allocation for rare diseases. Hastings Center Report 42(1):27-34.

Lenke, R. R., and H. L. Levy. 1980. Maternal phenylketonuria and hyperphenylalaninemia. New England Journal of Medicine 303(21):1202-1208.

Levy, H. L. 2021. Robert Guthrie and the trials and tribulations of newborn screening. International Journal of Neonatal Screening 7(1):5.

McCandless, S. E., and E. J. Wright. 2020. Mandatory newborn screening in the United States: History, current status, and existential challenges. Birth Defects Research 112(4): 350-366.

NCHS (National Center for Health Statistics). 2024. Birth data. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/births.htm (accessed July 31, 2024).

NHGRI (National Human Genome Research Institute). 2014. About phenylketonuria. https://www.genome.gov/Genetic-Disorders/Phenylketonuria#al-1 (accessed July 25, 2024).

Ojodu, J., S. Singh, Y. Kellar-Guenther, C. Yusuf, E. Jones, T. Wood, M. Baker, and M. K. Sontag. 2017. NewSTEPs: The establishment of a national newborn screening technical assistance resource center. International Journal of Neonatal Screening 4(1):1.

Paul, D. B. 1998. The history of newborn phenylketonuria screening in the US. In Promoting safe and effective genetic testing in the United States, edited by N. A. Holtzman and M. S. Watson. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Paul, D. B., and J. P. Brosco. 2013. The PKU paradox: A short history of a genetic disease. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

Rothenberg, M. B., and E. M. Sills. 1968. Iatrogenesis: The PKU anxiety syndrome. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry 7(4):689-692.

Rothwell, E., R. Anderson, and J. Botkin. 2010. Policy issues and stakeholder concerns regarding the storage and use of residual newborn dried blood samples for research. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice 11(1):5-12.

Rule, J. 1965. Screening of newborn infants for metabolic disease: Committee on fetus and newborn. Pediatrics 35:499-501.

Sterman, J., and D. Molina. 2023. Tasked with critical testing, newborn screening programs feel pinch of funding struggles. InvestigateTV. https://www.investigatetv.com/2023/05/22/tasked-with-critical-testing-newborn-screening-programs-feel-pinch-funding-struggles/ (accessed August 2024).

Susanna Haas Lyons Engagement Consulting. 2024. What we heard: Engagement summary for committee on newborn screening: Current landscape and future directions. Washington, DC: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Tarini, B. A. 2007. The current revolution in newborn screening. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 161(8):767-772.

Tarini, B. A., D. A. Christakis, and H. G. Welch. 2006. State newborn screening in the tandem mass spectrometry era: More tests, more false-positive results. Pediatrics 118(2):448-456.

Therell, B. L., and J. Adams. 2007. Newborn screening in North America. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 30(4):447-465.

Turnock, B. J., and C. Atchison. 2002. Governmental public health in the United States: The implications of federalism. Health Affairs 21(6): 68-78.

Van Vliet, G., and S. D. Grosse. 2021. Newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism and congenital adrenal hyperplasia: Benefits and costs of a successful public health program. Médecine Sciences 37(5):528-534.

Watson, M. S., M. A. Lloyd-Puryear, and R. R. Howell. 2022. The progress and future of US newborn screening. International Journal of Neonatal Screening 8(3):41.

Wilson, J. M. G., and G. Jungner. 1968. Principles and practice of screening for disease. Public Health Papers 34. Geneva: World Health Organization.