Newborn Screening in the United States: A Vision for Sustaining and Advancing Excellence (2025)

Chapter: 2 Current Landscape of Newborn Screening in the United States

2

Current Landscape of Newborn Screening in the United States

“Our daughter’s newborn screen changed the entire course of our lives . . . The support and education we have received since the positive result has been a blessing. It is knowledge that every family deserves.” – Parent

For more than 60 years, public health newborn screening (NBS) has directly touched the lives of essentially all babies born in the United States. The public health impacts of newborn screening are felt across society, but perhaps most profoundly by infants born with serious conditions screened for at birth, along with their families and caregivers. These achievements are made possible by a vast array of individuals, organizations, infrastructure, processes, and funding mechanisms that compose an informal NBS system that supports public health newborn screening for approximately 3.6 million babies born across the country each year.

Before considering the future for public health newborn screening, understanding the current landscape is critical. This chapter provides context on the history, goals, and implementation of public health newborn screening using dried blood spots in the United States;1 discusses the roles of key players in newborn screening; and identifies developments that may bring new opportunities and raise new questions.2

___________________

1 As reflected in Chapter 1, newborn screening encompasses dried blood spot, hearing loss, and congenital heart defect testing. The scope of this report is limited to dried blood spot screening in the United States.

2 Descriptions of the roles and structures of federal and nonfederal activities relevant to newborn screening are current as of March 24, 2025, including the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children.

OVERVIEW OF PUBLIC HEALTH NEWBORN SCREENING IN THE UNITED STATES

Public health newborn screening is intended to support both the health of individuals and that of the U.S. population overall (Brosco et al., 2015). It is carried out and supported by a large and varied network of public health and private laboratories, public health follow-up programs, clinics, research organizations, private companies, and government entities, yet unlike many other sprawling bureaucratic systems, it is experienced by each family individually during what many consider to be among the most momentous occasions of their lives—the birth of a child.

Terminology Used in this Report

This report distinguishes three distinct, yet interrelated domains related to newborn screening: public health NBS programs, the public health NBS system, and the broader NBS ecosystem. These distinctions help clarify roles, responsibilities, and the scope of activities involved in the screening, identification, and treatment of newborns.

NBS programs: Public health newborn screening is implemented by 56 separate public health NBS programs covering individual U.S. states and territories with the goal of identifying babies at risk of certain conditions and connecting them to clinical care.3

Public health NBS system: The successful delivery of newborn screening as a public health service depends on partnerships beyond individual NBS programs. The public health NBS system refers to all the partners directly involved in implementing public heath newborn screening. This public health NBS system includes state- and territorial-run NBS programs; state and territorial entities that oversee and support the operations of NBS programs; offices, advisory committees, and programs within federal agencies that provide guidance and support to NBS programs; clinical care providers and infrastructure involved in executing newborn screening for all infants and follow-up to confirm and connect those identified as at risk; partnerships with patient and family organizations, nonprofit entities, and professional associations tied directly to policy and practice of public health NBS; and others.

Broader NBS ecosystem: The report uses the term NBS ecosystem to represent the broadest scope of activities related to newborn screening. This ecosystem includes the NBS system and all sectors that interact with and influence newborn screening beyond the public health framework.

___________________

3 There are 56 newborn screening programs, including all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Programs are run by states and territories, but for brevity, the report will refer to these as state-run programs.

This includes activities providing long-term clinical care and support for affected infants and families, research to better understand the genetic basis, natural history, and detection of diseases in newborns and develop new tools, technologies and treatments, additional or complementary forms of screening carried out in clinical settings (separate from the sample collection and screening carried out through public health NBS), and the broader array of public- and private-sector efforts and organizations that support relevant research and clinical care.

By delineating these three domains, this report aims to provide a more structured understanding of the NBS landscape. Recognizing these distinctions enables more precise discussions to enhance the effectiveness and sustainability of public health NBS efforts.

The next section provides an overview of the NBS process as families experience it. This section also expands on the descriptions above to describe the array of processes and players involved in implementation of the public health NBS system and the broader NBS ecosystem.

How Families Experience Public Health Newborn Screening

Although there is wide variation in how public health newborn screening on dried blood spots is carried out across the United States, in general, the process can be broken down into three main steps (Figure 2-1) (HRSA, 2023b; NICHD, n.d.).

Families may learn about newborn screening before the birth of their child, or they may not know of its existence until a nurse comes to collect a blood spot from their newborn, or they may never know (Botkin et al., 2016). In most programs, there is no formal opt-in process, although families do

NOTE: NBS = newborn screening.

have the option of opting out in most jurisdictions (President’s Council on Bioethics, 2008).4 To collect the blood spot, a nurse, midwife, or technician pricks the baby’s foot with a small needle, a procedure known as a “heel stick.” A few drops of blood are then extracted from the baby’s foot and applied to a filter paper card. A nurse, midwife, technician, or hospital or birth center clerk records additional details about the infant on the card (such as name, sex, weight, race and/or ethnicity, and contact information for the baby’s parents and primary care provider). The blood spot is then transported to a laboratory for testing. Results from testing are transmitted to state- or territorial-run follow-up programs that then communicate findings with the baby’s health care provider, either directly or through office personnel, and in some cases, directly with the family. If the results suggest that the baby may have a health condition the screening process is intended to detect, health care providers and NBS program personnel work together with the family to refer the infant for further retesting as needed, diagnostic evaluation and confirmatory testing, and clinical care (HRSA, 2023b; NICHD, n.d.).

This process is intended to happen quickly. According to timeliness goals established in 2015, the blood spot should be collected within 48 hours after birth, the blood spot should arrive at the laboratory for testing within 24 hours of collection, and all tests should be completed within the infant’s first 7 days of life (HRSA, 2017). For certain time-critical health conditions (e.g., maple syrup urine disease), the laboratory aims to communicate any presumptive positive results to the baby’s health care provider by the time the baby is no more than 5 days old (HRSA, 2017).

Box 2-1 includes definitions of terms relevant to the screening and diagnosis of conditions in infants.

Players and Processes Involved in NBS Program Implementation

NBS programs are implemented at the state or territorial level with decision making and operations largely under state or territorial authority (Andrews et al., 2022; HRSA, 2023a; Watson et al., 2022). There is no central or integrated system for laboratory testing of newborn blood spots, and the 56 NBS programs use the services of an array of NBS public health laboratories and privately run laboratories (Dubay and Zach, 2023).5

___________________

4 Two exceptions are Wyoming, which requires parental informed consent (see https://health.wyo.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Updated-Newborn-Screening-Rules-12-2019.pdf), and Nebraska, which does not permit parents to opt out of screening (see https://law.justia.com/cases/nebraska/supreme-court/2008/1136.html).

5 See https://www.newsteps.org/data-center/state-profiles?q=data-resources/state-profiles (accessed September 26, 2024) for up-to-date information on each state or territory’s newborn screening program, including their responsible laboratory.

BOX 2-1

Terms Relevant to the Screening and Diagnosis of Conditions

Screening test: The systematic application of determinations (i.e., measurement procedures, physiological evaluations, or assessments) among a defined population (e.g., newborns) with the goal of detecting individuals at sufficient risk for a specific disease, group of diseases, or phenotypic difference to merit additional investigation or guide preventive action.

Diagnostic testing: Also called confirmatory testing. A test to prove or disprove the presence of a specific disease, group of diseases, or phenotypic difference suspected based on screening results. For newborn screening and identity confirmation, confirmatory testing must be performed on a new specimen, rather than on any existing screening specimen.

First-tier screen: A single test, combination of tests, physiological measurement, or assessment performed on all newborns to screen for a disease, group of diseases, or phenotypic difference as the first step in the laboratory screening algorithm.

Second-tier screen: Also called reflex testing. Additional test, physiological measurement, or assessment, performed as a second step in a laboratory screening algorithm on a subset of newborns, that uses the initial screening specimen (i.e., specimen recollection not necessary) when first-tier screening results are out of range.

In-range screening result: Also called expected range. The range of values for a measure in a typical healthy population.

Out-of-range screening result: Test result that is outside the expected range of testing results.

Borderline result: A term sometimes used for an out-of-range screening result that is close to a program-established screen-positive cutoff value and that indicates moderate risk/possible disease, rather than high risk/probable disease.

Screen negative: A final, reportable result for a disease, group of diseases, or phenotypic difference, based on the NBS result(s) and laboratory screening algorithm, indicating that the risk for that disease, group of diseases, or phenotypic difference is low and that no additional NBS follow-up is needed

Screen positive: A final, reportable result for a disease, group of diseases, or phenotypic difference, based on the NBS result(s) and laboratory screening algorithm, indicating that the risk for that disease, group of diseases, or phenotypic difference is higher and that additional follow-up is needed.

Screen inconclusive: A final, reportable result based on the NBS result(s) and laboratory screening algorithm for a screened disease, group of diseases, or phenotypic difference, indicating the inability to accurately interpret the screening result, typically leading to a request for a repeat dried blood spot specimen.

False-positive result: Screen-positive result in an unaffected newborn.

False-negative result: Screen-negative result in an affected newborn.

SOURCE: CLSI, 2023.

Although the federal government provides guidance and some support for these programs, the federated nature of NBS programs across the United States has led to substantial variation in how screening is implemented in different places, which is discussed in greater detail below.

Looking behind the scenes at the three main steps in the public health NBS process reveals a complex array of processes and players that make the NBS system run (Kanungo et al., 2018). During the blood spot collection step, the main players involved include newborns and their families; personnel who take and handle the blood spot at the hospital, birth center, or home birth setting; and those involved in transporting the sample to a laboratory for testing (Kanungo et al., 2018). The specific processes determining where, when, and how samples are collected, processed, and transported may be influenced by legal mandates and rules, funding mechanisms, and various state and institutional policies (HRSA, 2023b).

During the testing step, key considerations include what conditions are tested, what assays are performed, and cutoff values for what is considered in or out of range. Laboratories and NBS programs are the groups most directly involved in this step day to day. However, the practices and processes they use are determined by a wide range of additional partners and factors across the NBS ecosystem, including the advisors, advocates, and lawmakers involved in determining what conditions are included and how laboratories operate; scientific research enterprise, which contributes to the evidence about conditions that may be selected for screening; and the research, industry, and government entities involved in test technology development and capacity.

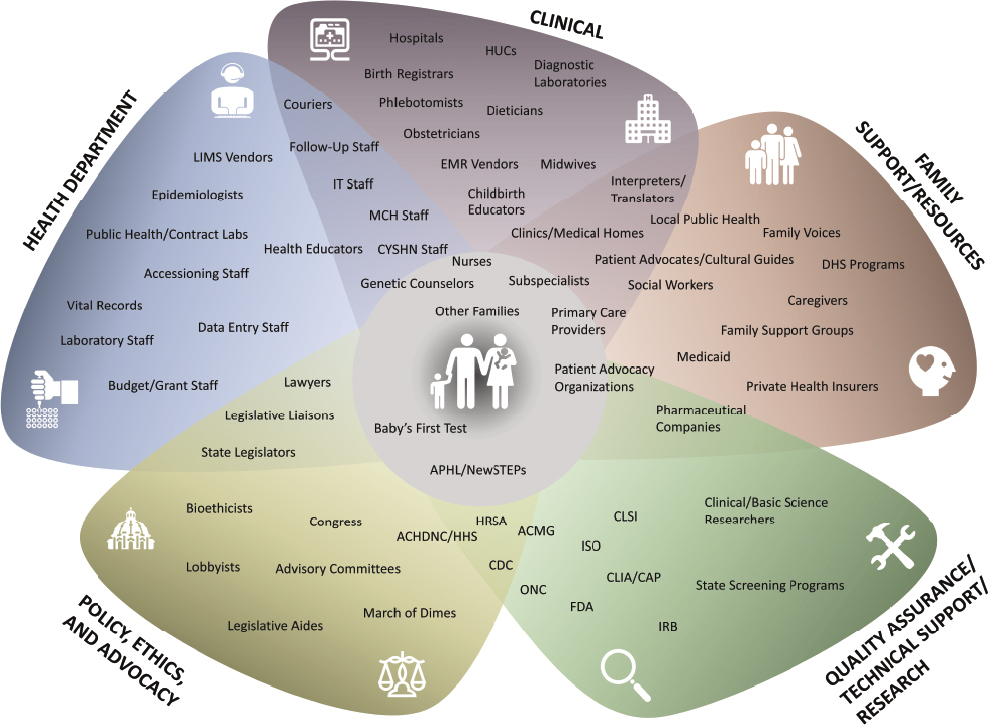

The results of laboratory testing determine the next steps of followup communication, diagnostics, and care. Results can be categorized as screen positive, screen negative, screen inconclusive, false positive, or false negative (see Box 2-1) (CLSI, 2023). If the results are in range for all tests performed, no further testing is done, and the results are made available to the baby’s primary care provider who may share them with the family. If the results are out of range, this triggers additional testing and follow-up, a process that can involve NBS program personnel, primary care providers, specialty clinicians, and families (HRSA, 2023b). If a diagnosis is confirmed for a condition, health care providers may recommend intervention or monitoring (HRSA, 2023b). Health care systems and policies, payors, patient advocates, and families can all play a role in determining the follow-up care received by people born with serious conditions. Box 2-2 briefly summarizes the roles of key players in the broader NBS ecosystem. Box 2-3 summarizes the roles of federal partners involved in newborn screening. Figure 2-2 provides further detail on the many players involved in implementing and supporting newborn screening.

BOX 2-2

Key Players Across the Broader NBS Ecosystem

Newborns and their families: Newborns receive public health newborn screening so that those born with certain serious health conditions can be identified and referred for treatment, which can extend their lives and improve quality of life. Families interact with the NBS system when a blood spot is taken and when the results are communicated during follow-up.

NBS programs: NBS programs run by U.S. states and territories implement newborn screening for babies born in that state or territory. Not every state program has its own laboratory; some will contract services from other states’ laboratories or private laboratories, but every program performs their own follow-up activities. Programs may receive guidance and other forms of support from federal, state, territorial, and other sources, but they operate independently under state or territorial authority.

Federal partners: Federal agencies and advisory bodies provide guidance regarding conditions recommended for screening; issue grants; support research; provide quality assurance and control support; and perform some oversight and regulatory functions relevant to newborn screening, including reviewing test devices and laboratory protocols. There is no formal federal oversight mechanism for newborn screening as a whole and no direct federal source for routine programmatic funding of NBS programs.

State and territorial legislators and policy makers: State and territorial legislators and policy makers contribute to NBS programs through various levers. State and territorial legislatures have the authority to establish and regulate the programs themselves, direct how programs will be administered, make determinations about NBS fees, and allocate federal funding and resources to these programs. State and territorial legislatures may influence which conditions are added to the screening panels directly via legislation or indirectly by authorizing state health departments to do so.

Patient advocates: Advocates play an important role in raising awareness of serious, often rare, disorders, which are often included within the umbrella of rare disease; encouraging their inclusion among the disorders selected for newborn screening; educating families about newborn screening and rare diseases; and helping to facilitate access to care among families of children born with serious disorders. Advocates also contribute to evidence collection to support condition nomination; financially support research initiatives related to newborn screening and advocacy efforts to expand NBS programs; and advocate for federal- and state-level programmatic funding for NBS programs.

Health care providers and health care systems: Health care providers communicate with families about newborn screening, collect blood spots for testing, and convey the results back to families. Providers and health care systems carry out clinical and administrative processes as required by NBS programs in both hospital birth settings, birthing centers, and midwife-facilitated home births. Primary care providers and specialty clinicians facilitate diagnostic testing and clinical care for infants identified as at risk via newborn screening.

As the process moves from screening to diagnosis to treatment and long-term follow-up, the responsibility for follow-up transitions from the NBS program to health care systems.

Payors: Health insurers and programs such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program determine and comply with policies regarding coverage of fees for care related to newborn screening, which may include fees related to blood collection, follow-up diagnostic testing, and clinical care.

Researchers and research organizations: Researchers and research organizations produce the scientific evidence that advisory bodies and NBS programs use to inform decisions about which conditions to screen, which testing methods to use, and best practices for providing clinical care. Researchers also investigate ethical, legal, and social issues related to newborn screening to inform policy and practice.

Industry: Private companies provide for purchase laboratory equipment and supplies necessary to conduct newborn screening. Some state- and territorial-run programs use private laboratories to screen their dried blood spots. Private companies also develop new screening and diagnostic tools as well as drugs or other treatments for disorders. Industry often provides financial support for selected research initiatives related to newborn screening and advocacy efforts to expand screening programs.

SOURCE: Andrews et al., 2022; APHL, 2015; HRSA, 2023b; Severin and Jones, 2023; Watson et al., 2022.

BOX 2-3

Federal Partners Involved in Newborn Screening

The primary federal partners involved in newborn screening include the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (HHS, 2015). Each agency works with its partners to support newborn screening, including through ex officio membership on the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children, described below.

HRSA: HRSA provides grants and programmatic support for state and territorial NBS programs in their efforts to implement screening for new conditions and provide appropriate follow-up care for children with serious conditions identified via newborn screening. HRSA also administers processes related to the Federal Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children (ACHDNC).

ACHDNC advises the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on newborn and childhood screening, including the appropriate application of tests, technologies, policies, guidelines, and standards to effectively reduce morbidity and mortality in newborns with serious disorders. ACHDNC makes recommendations to the secretary on which conditions should be added to the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (HRSA, 2022a, 2024a).

FDA: FDA regulates in vitro diagnostics, a category of medical devices that includes the tests used for newborn screening. FDA does not perform any direct testing of devices but reviews data and protocols from tests conducted by device manufacturers and determines whether the device has substantial equivalence (if there is a similar existing device) or a reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness (if it is a new type of device) (Caposino, 2024; Watson et al., 2022). FDA also regulates drugs and biological products used to treat disorders, including overseeing approval processes for new products (Watson et al., 2022).

CDC: CDC’s Newborn Screening and Molecular Biology Branch supports quality assurance for laboratories and screening tools involved in newborn screening through the Newborn Screen Quality Assurance Program (CDC, 2024d). It also assists NBS programs in their efforts to implement screening for new conditions, works to improve screening test performance and interpretation, facilitates training and technology transfer, and provides a national data platform to improve quality and interpretation of NBS results – Enhancing Data-Driven Disease Detection in Newborns (CDC, 2024a,c). CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities also contributes to the broader NBS ecosystem through many avenues, including supporting other forms of screening relevant to infants, developing surveillance systems and registries, and creating resources for primary providers, patients, and their families (Boyle et al., 2012; CDC, 2024f).

NIH: NIH and its institutes fund research projects, infrastructure, and collaborations that provide evidence used for decision making around newborn screening. This includes research to understand diseases that are or may be selected for newborn screening; develop and improve screening and diagnostic tests; develop treatment and management strategies; investigate ethical, legal, and social implications associated with newborn screening; and facilitate translational research (Parisi, 2024; Watson et al., 2022).

AHRQ: AHRQ awards research grants and supports the dissemination of findings related to improving the safety and quality of public health systems and care delivery. It does not have a program specific to newborn screening but has supported research focused on assessing and improving NBS programs (Mistry, 2024).

NOTES: ACHDNC = Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children; ACMG = American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics; APHL = Association of Public Health Laboratories; CAP = College of American Pathologists; CLIA = Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments; CLSI = Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; CYSHN = Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs; DHS = Department of Human Services; EMR = electronic medical record; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; HHS = Department of Health and Human Services; HRSA = Health Resources and Services Administration; HUC = health unit coordinator; IRB = institutional review board; ISO = International Organization for Standardization; IT = information technology; LIMS = laboratory information management system; MCH = Maternal and Child Health; NBS = newborn screening; NewSTEPs = Newborn Screening Technical assistance and Evaluation Program; ONC = Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT.

SOURCE: Amy Gaviglio, Connetics Consulting. Used with permission.

DISORDERS INCLUDED IN PUBLIC HEALTH NEWBORN SCREENING

Phenylketonuria (PKU) was the first condition for which newborns were routinely screened in the United States (NICHD, 2017a). An inherited disorder affecting the body’s ability to metabolize the amino acid phenylalanine, PKU causes phenylalanine to accumulate in the body and interfere with brain development. If left untreated, it can lead to intellectual disability and seizures. Starting a low-protein diet in the first days of life can prevent these

issues; as such, identifying infants with PKU shortly after birth can dramatically improve quality of life for these infants and their families (NHGRI, 2014). The development of an inexpensive blood test for PKU in 1961 made it possible to screen for the disorder shortly after birth and begin treatment for those identified to have the disease (Levy, 2021). Routine PKU screening of newborns was enacted into Massachusetts law in 1963 and adopted by most other states within the decade that followed. The implementation of this routine screening is credited with virtually eliminating PKU as a cause of intellectual disability in the United States (NICHD, 2017a).

As a disorder that (1) affects health, (2) is detectable in newborns, and (3) has improved health outcomes when treatment is delivered presymptomatically, PKU is emblematic of the types of conditions that have historically been the focus of newborn screening (NHGRI, 2014; Schnabel-Besson et al., 2024). To achieve the public health goals of screening, it is important for screening to result in better outcomes than would have occurred in the absence of screening (Wilson and Jungner, 1968). This determination involves weighing multiple potential benefits and harms related to early detection and treatment for a given health condition. As science and technology have advanced and it has become feasible to detect and treat a variety of other medical conditions manifesting in newborns, an increasingly broad array of conditions has been deemed suitable for public health newborn screening (Currier, 2022).

While various federal advisory groups, research, and programs have supported and informed state NBS programs over the decades, the determination of how many and which disorders to screen has always rested with the individual state and territorial NBS programs (Fabie et al., 2019). This has led to substantial variation in the disorders included in public health newborn screening from state to state. By the early 2000s, some states screened for as few as 3 conditions while others screened for as many as 43 (ACMG Newborn Screening Expert Group, 2005). In 2003, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) established the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children (ACHDNC) to advise the secretary of Health and Human Services about newborn and childhood screening, and in 2010 the secretary established the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP), a list of disorders programs are encouraged to screen (HRSA, 2021).

Federal Processes for Selecting Disorders

The RUSP is the primary mechanism through which the federal government helps to guide state and territorial decisions about the selection of disorders for public health newborn screening. Informed by an expert analysis by the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) released in 2005, the RUSP was established in 2010 with an initial list of 29 core

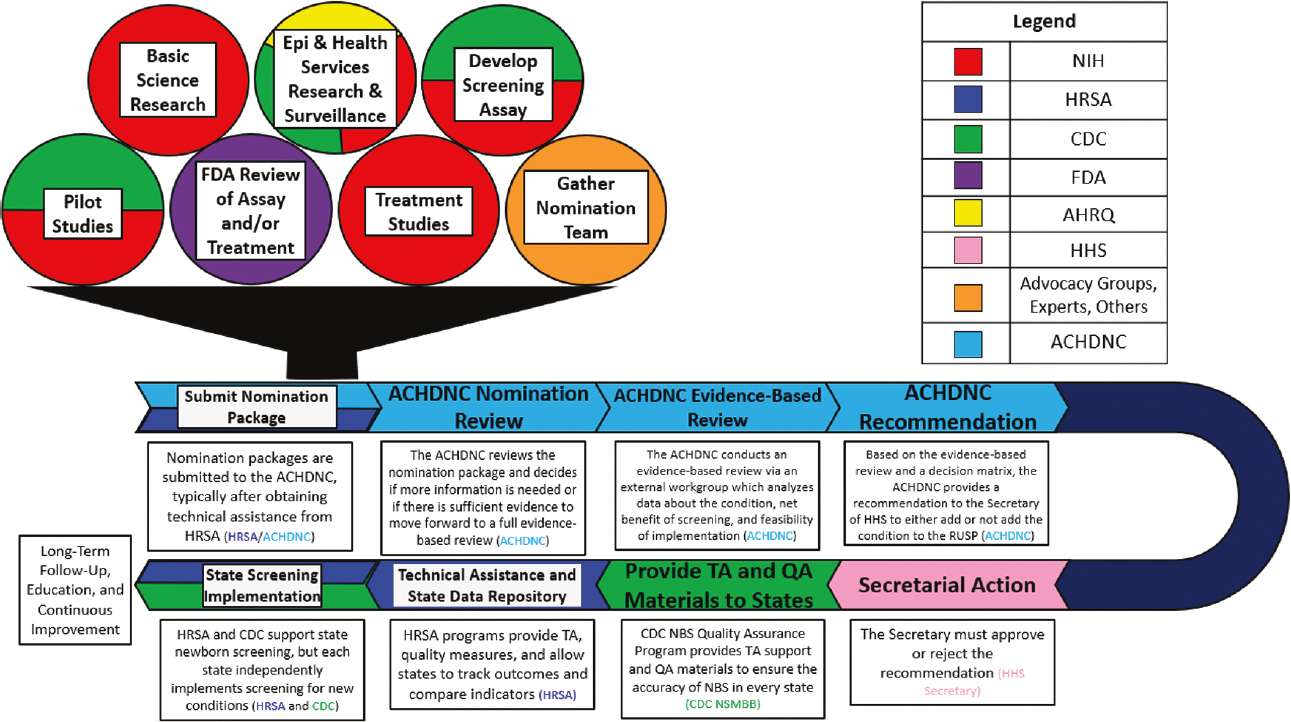

NOTES: ACHDNC = Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children; AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Epi = epidemiological; FDA = Food and Drug Administration; HHS = Department of Health and Human Services; HRSA = Health Resources and Services Administration; NIH = National Institutes of Health; NBS = newborn screening; NSMBB = CDC’s Newborn Screening and Molecular Biology Branch; RUSP = Recommended Uniform Screening Panel; TA = technical assistance.

SOURCE: Presented by Jeffrey Brosco, HRSA, January 26, 2024. Minear et al., 2022. CC PDM 1.0.

conditions identified as primary targets for screening and 25 secondary conditions (disorders that are detected in the differential diagnosis of a core disorder, but lack an effective treatment or are poorly understood) (ACMG Newborn Screening Expert Group, 2006).6 As of August 2024, the RUSP includes 38 core conditions and 26 secondary conditions (HRSA, 2024d). Only 2 of 56 programs currently screen for all 38 RUSP core conditions.7 Once added to the RUSP, there is not a formal mechanism for removing a condition if population screening reveals that the condition does not meets selection criteria (e.g., net benefit) (Kemper et al., 2014).

The process for adding conditions to the RUSP involves the collective efforts of hundreds of people across the NBS ecosystem (Figure 2-3).

___________________

6 ACMG released its report in 2005, and an executive summary was published in Genetics in Medicine in 2006.

7 See https://www.newsteps.org/resources/data-visualizations/newborn-screening-status-all-disorders (accessed January 28, 2025) for up-to-date information on the number of RUSP conditions screened by each program.

The submission of a preliminary nomination form to ACHDNC marks the beginning of the official process to add a condition to the core RUSP panel, but the process actually begins much earlier (Armstrong, 2024; HRSA, 2024c). Prior to submitting a full nomination package, nominators first submit a preliminary nomination form, which is considered by the Nomination and Prioritization workgroup of ACHDNC. The nominators can complete a full nomination package once the working group verifies that the following requirements are met for the condition: an NBS test is available; there is an agreed-upon case definition; a prospective population-based study has been conducted that has identified at least one infant with the condition; and identification before clinical onset allows provision of an effective, approved therapy.8 To generate a nomination package requires conducting and reviewing research on the health condition, its causes, and its effects; strategies for detecting the condition in newborns, including a population-based pilot study; and approved treatments for the condition (HRSA, 2022b).

Multiple federal and other partners play a role in funding, carrying out, and evaluating studies and technologies relevant to the condition to be nominated. This includes National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) support for basic and translational research; Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reviews of the screening assay and/or treatment; and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) contributions to disease surveillance, screening tool validation, and pilot studies for newborn screening using the proposed assay (Brosco, 2024). Critically, this process also relies on the establishment of a nomination team that typically includes patient advocates, scientific and medical experts, and other partners who gather and evaluate the evidence and assemble the nomination package, a process that typically takes several years (HRSA, 2022b).

After an initial review, the ACHDNC decides if sufficient evidence is available, and votes to assign, or not assign, the nominated condition to the external Evidence-Based Review Group (ERG). The ERG systematically reviews the evidence, models the expected effect on health outcomes if the condition were to be added to the RUSP, and assesses the feasibility of implementation by NBS programs. The goal of this review is to not only assess the potential benefits and harms of screening newborns for the disorder but also to identify gaps and anticipate challenges to implementation if screening were to be recommended (HRSA, 2024c).

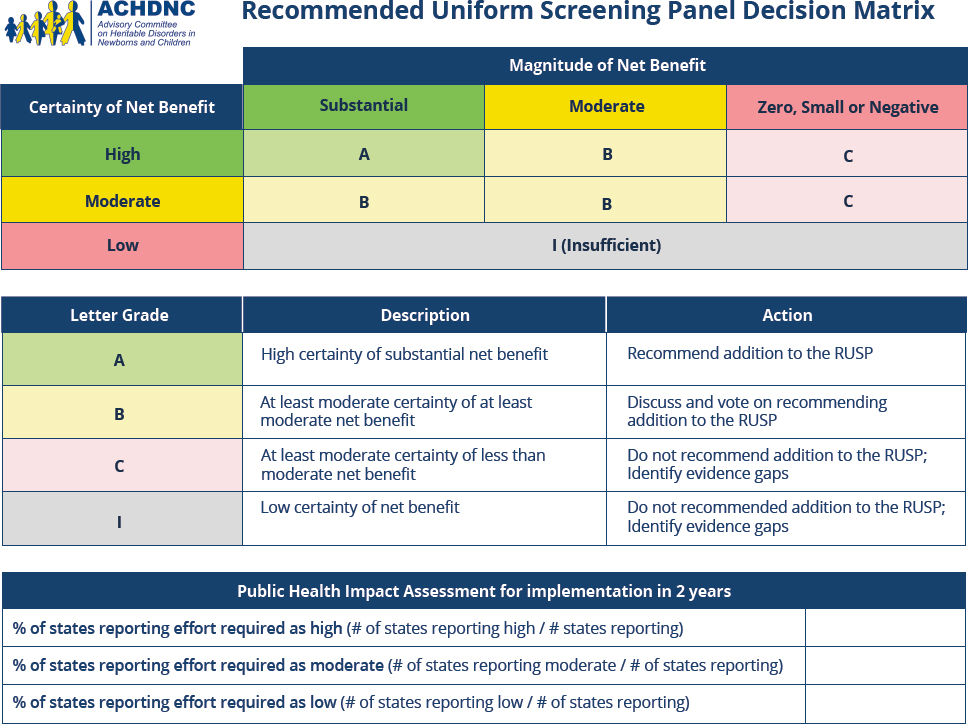

ACHDNC uses the evidence review group’s report along with a decision matrix (Figure 2-4) to make a recommendation to the secretary of HHS regarding whether the condition should be added to the RUSP. The decision matrix, updated in August 2024, prompts each committee

___________________

8 The nomination process was updated to include a preliminary nomination form in May 2024 in response to feedback from families, clinicians, and other affected individuals. See https://www.hrsa.gov/advisory-committees/heritable-disorders/rusp/nominate (accessed March 24, 2025).

SOURCE: HRSA, 2024e.

member to assess the net benefit of screening all newborns and the certainty of the evidence regarding the net benefit. Designations for net benefit were adapted from the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force with an A designation indicates a high certainty of net benefit and leads to recommendation for addition to the RUSP (Calonge, 2023). Using the decision matrix, members also assess the feasibility of implementing screening, and the readiness of programs to implement expanded screening (HRSA, 2024c), although cost-effectiveness of screening, diagnosis, and treatment is not usually considered in this process (Grosse et al., 2016). The decision matrix is a tool to support the committee’s decision making, but members ultimately make the decision that is then passed along to the secretary. The secretary then accepts or rejects the recommendation. If a condition is recommended for inclusion and that recommendation is accepted, the condition is added to the RUSP (HRSA, 2024c).

While ACHDNC and the RUSP are mechanisms for providing evidence-based guidance to state and territorial NBS programs, the process of adding conditions to the RUSP also poses challenges. One challenge is the length of time the process takes. According to Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) documentation, the shortest time elapsed from the submission of a nomination package to secretarial action was 21 months and the longest was 10 years, with most taking 3–4 years

(HRSA, 2022b). Several stages of review and decision making coupled with the frequency of ACHDNC meetings (only a few times a year) can contribute to the length of the RUSP process. The duration can be further prolonged by necessary resubmissions of nomination packages with additional information that required further research (HRSA, 2022b). Such information is often essential to inform how to screen for the targeted condition safely and effectively (see Box 2-4). While acknowledging the reasons behind the duration of the process, the RUSP process also faces scrutiny for its ability to keep up with medical advances and for the burden it places on the rare disease advocacy community (Andrews et al., 2022; Armstrong, 2024; Kennedy, 2024). These frustrations can drive some advocates to bypass the evidence-based RUSP review process, turning instead to state legislatures to expedite the addition of conditions to NBS panels (APHL, 2015; Susanna Haas Lyons Consulting, 2024).

A related challenge is the sheer amount of effort and time required to assemble the necessary evidence and clear the required reviews at each stage. Generating the evidence used as part of this process reflects an enormous undertaking across the NBS ecosystem—spanning basic science, translational and clinical research, technology development, and population-based pilot studies. These studies must be proposed, funded, conducted, and interpreted. Maintaining the attention and funding necessary to drive this evidence-generation process can also require significant effort on the part of advocacy groups (Armstrong, 2024).

Population-based pilot studies are a particularly onerous component of the nomination package that pose a “chicken or the egg” dilemma: to be considered for nomination to the RUSP for screening, a condition must have already been screened as part of a population-based study. These studies are important to demonstrate feasibility and public health impact (ACHDNC Pilot Studies Workgroup, 2016). However, they require significant funding and effort or may be initiated after a condition is added by a state following political advocacy, thus circumventing other evidence-based mechanisms for addition to newborn screening (APHL, 2015).

A final challenge, and one which could further compound the first two, is that emerging knowledge and technologies present a more complicated array of options—and a more complicated array of potential benefits and harms—for public health newborn screening (Currier, 2022). New technologies pose resource and expertise demands on state- and territorial-run programs, including purchasing new equipment, validating new testing processes, training personnel, storing data, handling sensitive genetic information, and more (Currier, 2022; Watson et al., 2022). Beyond the practical demands and challenges to programs, ethical, legal, and social questions are raised by employing new technologies in newborn screening (Grant, 2022; Ram, 2022; Ross and Clayton, 2019). As it becomes possible to test for an ever broader range of conditions, including

BOX 2-4

Case Study: SCID

The process by which severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) was incorporated into routine newborn screening provides an illustrative example of the complexity of the review, recommendation, and implementation processes for adding new conditions to screening panels; the many stakeholders and rights holders involved; and challenges related to assessing and implementing new screening technology.

SCID is a rare disorder in which a person’s immune system is compromised, leaving them extremely vulnerable to infection. There are several forms of the condition, most of which have a genetic cause. Because babies born with SCID do not have a normally functioning immune system, they can become seriously ill or die from infections. SCID can be effectively treated with a bone marrow transplant, gene therapy, and other established therapies (NIAID, 2019).

The addition of SCID to the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) marked the culmination of many years of effort on the part of physicians and researchers, individuals and families, state newborn screening (NBS) laboratories, SCID experts and advisors, patient advocacy groups, and other partners (Ballard, 2024). Advocacy for adding SCID to the RUSP started well before the RUSP existed, at the first meeting of the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children (ACHDNC) in 2004 (Ballard, 2024). In the years that followed, the development of an assay to measure a marker known as a T-cell receptor excision circle (TREC), which is absent or low in infants with SCID, made it more feasible to screen for SCID using dried blood spots (Chan and Puck, 2005). The first pilot study for TREC-based newborn screening for SCID began in Wisconsin in 2008 (Baker et al., 2010). ACHDNC initially voted against recommending SCID for the RUSP in 2009, citing five key evidence gaps including the lack of identification of a confirmed case through population-based screening, but in 2010 voted in favor of recommending SCID for the RUSP after receiving additional information to address these gaps (Geleske, 2010; HRSA, 2021).

SCID was officially added to the RUSP as a core condition shortly after the RUSP was established in 2010, and by the end of that year several states had begun routine screening (HRSA, 2021). However, the road to implementation was only just beginning; it was not until 2018—a full 8 years after SCID was added to the RUSP—that SCID newborn screening was adopted across all state and territorial NBS programs (Currier and Puck, 2021).

The implementation of universal newborn screening for SCID was associated with significant improvements in survival for babies born with SCID in the United States (Thakar et al., 2023). However, SCID’s path to the RUSP—and the long road to universal implementation—also highlights challenges. One challenge cited by those involved is that generating the evidence necessary for approval and urging the actions necessary for implementation required considerable time and effort on the part of advocates at every step (Ballard, 2024). Another challenge stems from the fact that the TREC test was the first DNA-based test to be proposed for newborn screening, creating a learning curve requiring decision makers, NBS laboratories, and other players to establish new frameworks and processes for reviewing the evidence for the test, supporting quality assurance and validation, and conducting pilot studies (HRSA, 2010). Lastly, unbiased

population screening for SCID using the TREC test presents the challenge of uncovering secondary findings of non-SCID T-cell lymphocyte deficiencies (Kwan et al., 2014). Best practices for follow-up of infants at risk for non-SCID T-cell lymphopenias remain unclear (Kubala et al. 2022). Non-SCID T-cell lymphocyte deficiencies are included as secondary RUSP conditions as secondary findings when screening for SCID (HRSA, 2024d).

As technology continues to advance and additional test modalities are proposed for newborn screening, similar issues may emerge for future disorders. In addition, even many years after the TREC test was developed and SCID was recommended for newborn screening, questions remain regarding best practices for screening, follow-up diagnostic testing, and treatment for babies born with SCID, as well as gaps in communication, data collection and reporting, and uneven access to specialized care (Currier and Puck, 2021, Gaviglio et al., 2023; Sheller et al., 2020). These challenges demonstrate that for many disorders selected for newborn screening, the job is not finished when a condition is added to the RUSP; there remains a need for continued investment in scientific research and program evaluation to elucidate best practices, improve public health systems, and ensure the best possible outcomes for people born with serious disorders.

adult-onset conditions, carrier status, and others, there is not always a clear action associated with the test results, a clear benefit to screening in the newborn period, or a complete understanding of the potential psychosocial harms (Currier, 2022). Such considerations can make it more difficult to assess the evidence and guide decision making.

A case study describing how severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) was added to the RUSP (Box 2-4) illustrates how the process works and some of the challenges involved.

State Processes for Selecting Disorders

Although the RUSP exists to help inform and harmonize newborn screening across the country, there is no federal law or regulation requiring state NBS programs to align with the RUSP (HRSA, 2024d). Each NBS program establishes its own processes for selecting disorders and implementing screening according to state and territorial laws and regulations. The responsibility for carrying out decision-making processes around NBS panels (and overseeing screening programs) typically rests with state or territorial public health departments, the state board of health, or a combination of such bodies (HRSA, 2024b). Some states have laws or proposed legislation requiring public health departments to align their NBS panels with the RUSP, while other states have no requirements regarding RUSP alignment (EveryLife Foundation for Rare Diseases, n.d.).

Most states have expert committees (akin to a state-level ACHDNC) that consider conditions nominated for screening, review the evidence, and make a formal recommendation to approve or reject the nomination (APHL, 2015).9 This process often involves receiving public comments and assessing projected costs and logistical considerations in addition to considering the scientific evidence about the disorder, its detection, and its treatment. States often use criteria similar to those used by ACHDNC to guide decisions at a national level, but they do so in a state context, gauging the expected benefits, harms, and feasibility of implementation in the context of the particular state or territory and its population (Montana DPHHS, n.d.). Moving through such state-level processes involved in reviewing, recommending, and implementing newborn screening for a new condition often takes several years (Singh et al., 2023).

Cost can be an important issue at the state and territorial level, with some states performing cost-benefit analyses comparing the status quo to adding the nominated condition to the updated screening panel (Thompson, 2024). Adding a condition to a state or territory’s NBS panel typically increases the cost of screening, and while some federal grants may be available to offset this (see Chapter 4), most states usually raise NBS fees to accommodate adding new conditions (Dorley, 2024).

IMPLEMENTATION OF NBS PROGRAMS

Newborn screening in the United States is carried out by state and territorial NBS programs. These programs receive guidance and support from federal entities but operate independently under the authority of their state or territory. As a result, programs vary substantially.

Program Oversight and Operations

NBS programs are generally run by state or territorial health departments with oversight and support from state legislatures and other officials, boards of health, or other entities (GAO, 2003).10 Coordinating a state NBS program is a complex endeavor. In addition to determining which conditions to screen, states must address countless details about how screening is performed, including policies and practices for blood spot collection and parental consent, qualifications and training for personnel, the laboratory equipment and test protocols to be used, how results are

___________________

9 See https://www.newsteps.org/resources/data-visualizations/newborn-screening-advisory-committees (accessed September 26, 2024) for up-to-date information on whether programs currently have an advisory committee, if the advisory committee is mandatory or voluntary, meeting frequency, and other details.

10 See https://www.newsteps.org/data-center/state-profiles?q=data-resources/state-profiles (accessed January 30, 2025) for additional details about how each state and territorial program is run.

communicated and clinically assessed, and how all these activities will be financed (Dubay and Zach, 2023; Lewis et al., 2011). These factors can also change as laws, technologies, and funding structures evolve over time, necessitating careful management and frequent adjustments.

The addition of a new condition to a state’s screening panel sets off a cascade of additional tasks and decisions on top of the program’s continuing operations. When a new condition is approved for the state panel, the NBS program must do the following:

- coordinate with hospitals, laboratories, health care providers, payors, and others to identify, validate, and establish standard operating procedures for the testing methods to be used;

- establish expected ranges for interpreting the results;

- identify equipment needs and secure the necessary funding, facility space, and infrastructure to perform the new tests;

- incorporate the new condition into electronic data management and tracking systems;

- establish follow-up protocols;

- identify health care providers and specialists as needed; and

- educate and train personnel.

All of this happens within systems that often require complex processes for establishing contracts, procuring materials, hiring staff, obtaining approvals, and communicating with stakeholders. In addition, all of these decisions have financial implications. When adding a new condition for screening, states must identify a funding mechanism to cover the initial implementation and continued ongoing operations (Dorley, 2024; Thompson, 2024).

The complexity of operating NBS programs and onboarding new conditions contributes to a significant lag time between when a new condition is added to the RUSP and/or state screening panel and when screening is universally implemented. According to one analysis, implementation for disorders added to the RUSP between 2010 and 2018 took as few as 2.1 years on average for spinal muscular atrophy and as many as 4 years on average for Pompe disease among states and territories that incorporated those conditions into their screening panels (Singh et al., 2023).

Variation Across Programs

Since the inception of newborn screening in the 1960s, there has been substantial variation in how NBS programs operate (Watson, 2006). As discussed above, programs have long varied regarding the number and types of conditions they screen. Program implementation also differs widely (see Box 2-5).

BOX 2-5

Variability Across State and Territorial NBS Programs

Considerable variability exists across state- and territorial-run newborn screening (NBS) programs. Each program must comply with the legislative requirements of their jurisdiction and implement the program using the funding, workforce, and other resources available to them. As such, programs vary in terms of the number of core Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) conditions screened, the timeliness with which results are returned, and the fee charged to hospitals for screening each newborn, among other factors. NBS programs also have variable health information technology (IT) infrastructure at hand to ensure rapid, accurate, and effective communication between laboratories, follow-up programs, and clinical care. Health IT infrastructure can also allow for greater interoperability and comprehensive data capture as greater emphasis is placed on longitudinal follow-up for infants identified through newborn screening (Abhyanker et al., 2015). Below provides a snapshot of the variability of state-run programs across the United States.

Core RUSP conditions screened: State and territorial programs screen from 31 to 38 of the 38 conditions on the RUSP.

Timeliness: In 2022, 18 programs reported from 3 percent to 100 percent of time-critical results within 5 days birth, with a median of 57 percent of results reported (NewSTEPs, 2023).

Fees: For programs that charge fees (typically billed to hospitals), fees for each baby screened range from $30 to $258 with a median cost of $185. Five programs do not charge a fee.

Electronic messaging: There are 15 programs that can both send and receive Health Level Seven (HL7) electronic messaging, 3 programs can only receive HL7 electronic messaging, 3 programs can only send electronic messaging, and 25 programs can neither send nor receive electronic messaging; 10 programs did not provide data.

Information systems:

- Laboratory information management system (LIMS): 23 programs use Revvity, 14 use Neometrics/Natus, 6 use internally developed programs, 3 use StarLims, 9 use other LIMS, and 1 program did not provide data.

- Follow-up information management system: 16 programs use Revvity, 10 use Neometrics/Natus, 17 use internally developed programs, 2 use StarLims, 9 use other information systems including Excel, and 1 program did not provide data.

- Only 25 programs use the same information systems for both laboratory and follow-up.

NOTE: See https://www.newsteps.org/data-center/dashboards-and-reports (accessed January 30, 2025) for up-to-date information on each state or territory’s NBS program, including their responsible laboratory.

Although the procedure for collecting a blood spot is consistent across states and collection contexts, the processes surrounding collection vary, and are not always well documented. For example, there are few data about how and when parents are informed about newborn screening. Most state programs have no formal opt-in process but allow parents to opt out of newborn screening for religious or other reasons (President’s Council on Bioethics, 2008). The information that is collected on the sample card (including details about the infant such as race or ethnicity, home address, and other features) also varies from state to state. In addition, some states perform only a single screen in the first days of life, while others perform an additional screen 12 weeks later with a new dried blood spot sample.

These second screens are typically collected by the primary care provider and sent for testing with the goal of increasing identification of children for certain conditions (e.g., congenital hypothyroidism) (HRSA, 2023b; Shapira et al., 2015). This second screen is different from second-tier or reflex testing which is performed for only a subset of infants who have an out-of-range result on their initial screen; second-tier screening is performed using the same blood spot, whereas second screen uses a newly collected blood spot (Caggana et al., 2013).

Testing of blood spots may be done in state laboratories, university centers, private laboratories, or even be outsourced to laboratories in other states (GAO, 2003; NewSTEPs, 2021). Laboratories may use different tests or methodologies to detect risk for the same condition with variable accuracy, specificity, and sensitivity (Dubay and Zach, 2023; McGarry et al., 2023; Rehani et al., 2023). Most NBS programs operate their laboratories 6 days per week and their follow-up offices 5 days per week, although operational hours can range between 5 and 7 days per week for both.11 Programs that operate for more days per week are more likely to achieve compliance with timeliness goals (Sontag et al., 2020).

The funding mechanisms for supporting NBS programs also vary from state to state (Johnson et al., 2006). While many programs receive state funding and federal grants, most funding for NBS program operations comes from fees that NBS programs charge to birthing facilities. These fees are often bundled with other charges for newborn care that are billed to insurance companies (Costich and Durst, 2016). Newborn screening is required coverage for most health plans under the Affordable Care Act.12 Therefore, insurance will cover the cost of newborn screening

___________________

11 See https://www.newsteps.org/resources/data-visualizations/operating-days-and-hours (accessed September 26, 2024) for up-to-date information on each program’s operating days and hours for both laboratory and follow-up.

12 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-148, 124 Stat. 119.

for most newborns, either through Medicaid—which covers the cost of approximately 40 percent of births in the United States annually (CMS, 2024)—or private insurance. Hospitals are required to perform screening even for families who cannot pay (NICHD, 2017b). However, uninsured individuals may be asked to pay the NBS fee depending on the program.13 For those delivering outside of hospital settings, these fees can be a challenge as home births and birth center births are much less likely to be covered by insurance (AABC, 2024; Coupal et al., 2021; MacDorman and Declerq, 2019). Birthing centers and birth workers report that they often assume the cost of NBS tests or pass the cost onto families (AABC, 2024). The fees NBS programs charge range from $0 to over $200 per blood collection card purchased or processed, with most programs’ fees falling between $51 and $150 per card.14 An analysis revealed no correlation between the fees charged and the number of conditions screened, laboratory operating hours, or follow-up activities (Ojodu, 2024).

Finally, programs differ in their processes for following up on screening results. Each NBS program develops its own protocols for testing blood samples, with many using a tiered system to analyze secondary parameters and increase the specificity of results for screens that fall outside of expected ranges in first-tier testing (Furnier et al., 2020; Rehani et al., 2023). Programs may vary in their processes for handling repeat screening or additional diagnostic testing for presumptive positive, borderline, or unsatisfactory results, as well as the involvement of NBS program personnel and laboratories versus primary care providers or specialty clinicians in these processes (HRSA, 2023b). As infants with serious health conditions transition from screening to diagnosis and care—thus transitioning from a public health program to the health care system—the extent of NBS program involvement in facilitating clinical care or ongoing surveillance can also vary.

Timely identification of infants with serious disorders is at the core of the value proposition for newborn screening; as such, compliance with timeliness goals is a key quality indicator for NBS programs. According to timeliness goals articulated by ACHDNC in 2015, blood samples should be collected within 48 hours after birth and received at the laboratory within 24 hours of collection, presumptive positive results for time-critical conditions should be communicated to the baby’s health care provider no later than 5 days of life, and presumptive positive results for all other conditions should be communicated to the baby’s health care

___________________

13 For example, see https://doh.wa.gov/you-and-your-family/infants-and-children/newborn-screening/screening-cost (accessed February 19, 2025).

14 See https://www.newsteps.org/data-resources/reports/nbs-fees-report (accessed September 26, 2024) for up-to-date information on fees associated with each program.

provider no later than 7 days of life (HRSA, 2017). Data for 2012–2015 showed that most states were not meeting these goals for 95 percent of specimens (GAO, 2016). Recent data collected from 25 state-run programs indicated an improvement in timeliness metrics especially for programs open 7 days per week; however, timeliness goals are still not being fully met (NewSTEPs, 2023; Sontag et al., 2020). Other quality indicators that have been used to assess NBS programs include percentage of infants lost to follow-up (i.e., infants that did not receive a confirmed diagnosis or diagnosis ruled out), percentage of newborns not screened, percentage of unsatisfactory specimens, and more.15

Many factors may influence states’ ability to meet timeliness goals and other quality indicators. For example, the task of transporting samples from isolated communities in Alaska to a testing laboratory in Iowa is drastically different from transporting samples from a major university hospital to a laboratory on the same campus.16 The vulnerability of systems to events such as power outages, blizzards, and hurricanes can also affect NBS program performance (National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, 2017). The complexity of the conditions being screened can also challenge timeliness. As with any program administered by state and territorial governments, NBS programs are also vulnerable to evolving legislative priorities and variability in state budget allocations. In addition, disease prevalence, population demographics, and clinical capacity for specialized management and treatment can be different between states, all of which affect newborn screening. While variation in the practice of public health newborn screening may be understandable and even inevitable given these circumstances, to fulfill the value proposition of newborn screening requires that such variability does not extend to the outcomes experienced by newborns and their families.

Support for Public Health NBS Programs

State and territorial NBS programs receive both programmatic and monetary support from federal sources. This support can take a variety of forms, from crosscutting resources intended to benefit all NBS programs to grants issued for specific NBS programs or activities. Organizations outside the federal government, such as professional organizations and advocacy groups, also provide support and resources to NBS programs and the NBS system as a whole.

___________________

15 See https://www.newsteps.org/data-center/quality-indicators?q=data-resources/quality-indicators (accessed September 26, 2024).

16 See https://www.newsteps.org/data-resources/reports/courier-system-report (accessed September 26, 2024).

Several laws have played an important role in federal activities relevant to public health newborn screening. Examples include the Children’s Health Act of 2000,17 which led to the establishment of ACHDNC; the Newborn Screening Saves Lives Act of 2007,18 which provided funding for various NBS activities and led to the establishment of the RUSP; and the Newborn Screening Saves Lives Reauthorization Act of 2014, which extended and expanded upon the 2008 legislation but expired in 2019 when it was not reauthorized a second time (HRSA, 2021).19 Although there is no direct federal source for routine programming support of NBS programs, programs can receive federal funding through Title V block grants and grants from the Heritable Disorders Program under the Children’s Health Act of 2000 (Johnson et al., 2006).

HRSA leads several efforts aimed at facilitating effective public health newborn screening across the country. In addition to its direct involvement administering ACHDNC and the RUSP, HRSA provides support to state and territorial NBS programs through state grant mechanisms known as NBS Propel and Co-Propel, a national coordinating center known as NBS Excel, and family engagement and leadership projects. These efforts began in 2023 and the period of performance for these grant programs will end in 2028. These efforts are intended to help NBS programs address state- or territory-specific challenges, support screening implementation for core RUSP conditions, and improve follow-up (HRSA, 2024a,e). Where particular gaps in access to follow-up and treatment have been identified (for example, in access to high-quality treatment and follow-up for sickle cell disease), HRSA also funds condition-specific programs to address these gaps (HRSA, 2023c).

A variety of federal, state, and nonprofit partners play critical roles in carrying out activities supported by HRSA. For example, the Association of Public Health Laboratories receives HRSA funding to develop and maintain the Newborn Screening Technical assistance and Evaluation Program (NewSTEPs),20 a program that provides data, technical assistance, and training to support some NBS programs. Another example is Baby’s First Test, an educational resource for families and health professionals (Baby’s First Test, 2024b). Baby’s First Test was initially funded through a cooperative agreement between HRSA and the nonprofit organization Genetic Alliance; it is now maintained through partnership agreements, licensing, and sponsorship (Baby’s First Test, 2024b).

___________________

17 Children’s Health Act of 2000, Public Law 106-310, 106th Cong., 2nd sess. (October 17, 2000).

18 Newborn Screening Saves Lives Act of 2008, S1858, 110th Cong., 1st sess., Congressional Record 153, No. 191, daily ed. (December 13, 2007).

19 Newborn Screening Saves Lives Reauthorization Act of 2014, HR1281, 113th Congress., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 160, No. 158, daily ed. (December 8, 2014).

20 See https://www.newsteps.org/ (accessed September 26, 2024). Although there are 56 newborn screening programs, only 53 are actively providing data to NewSTEPS.

CDC also provides substantial support to state NBS programs. Its efforts focus on building capacity directly within state NBS programs as well as through CDC’s Newborn Screening and Molecular Biology Branch, which provides a variety of services to support NBS laboratories. CDC activities have included issuing grants to support state implementation of screening for conditions added to the RUSP; developing a national contingency plan for ensuring continued NBS program operation during crises; providing reference materials and improving test performance for biochemical and DNA-based screening through its national Newborn Screening Quality Assurance Program; and providing technical assistance, training, and site visits to inform and enhance laboratory practices (CDC, 2024a,e).

In addition, CDC’s Enhancing Data-Driven Disease Detection in Newborns (ED3N) project is under way to establish a national data platform to improve the quality and interpretation of NBS results (CDC, 2024c). A new funding program starting in 2024 will establish a Center of Excellence to Enhance Disease Detection in Newborns with a goal of positioning NBS programs to adapt in response to new technological developments and meet increasing demands (CDC, 2024b).

These and other sources of support can play a vital role in facilitating quality assurance, operational improvements, and education and outreach to support high-quality NBS programs across the country. However, the availability of grants and other mechanisms of support does not automatically mean that all NBS programs will benefit from them. Lower-resourced states and programs may face greater challenges allocating staff resources toward applying for grants and taking advantage of various opportunities for programmatic support and improvement. Unchecked, this dynamic could lead to a situation where well-resourced NBS programs get stronger while federal channels of support do not always effectively reach the programs that could use them most.

COLLECTION AND USE OF BLOOD SPOTS

Blood samples are central to newborn screening. An examination of the practices and processes for the collection and use of samples—from obtaining consent for the initial heel stick all the way through to the eventual destruction of samples and data—highlights important facets of the current NBS system and some of the challenges it raises.

Consent and Sample Collection

Questions about parental consent have been raised throughout the history of newborn screening (Annas, 1982; Faden et al., 1982). When should parental consent be required, and when should parents be able

to opt out of screening? Can a parent’s right to refuse screening be outweighed by the potential harm that occurs if a child with a serious and treatable condition is not identified in time to fully benefit from treatment? When parents opt out of newborn screening, does it undermine not only their own child’s right to access screening but also the public health benefits of newborn screening more broadly?

Consent requires that a participant must be informed, demonstrate understanding, and voluntarily agree to participate. NBS programs take a variety of approaches to consent (King and Smith, 2016). Since newborns cannot speak for themselves, consent for newborn screening applies to the infant’s parent(s) or guardian(s). The vast majority of NBS programs take an opt-out approach, which assumes the baby will be screened unless a parent opts out, rather than requiring parents to affirmatively opt in. Most states allow parents to opt out for reasons of religious belief, and some allow parents to opt out for religious or personal reasons. A few programs include stipulations that parents should provide informed consent, be informed of their right to object, and/or be given a reasonable opportunity to opt out (President’s Council on Bioethics, 2008). Bioethical foundations underpinning newborn screening are explored further in Chapter 3.

Although NBS programs in general have thus far been allowed to set their own processes for obtaining consent or allowing parents to opt out of universal screening, these are not settled questions. Debates related to these matters have surfaced repeatedly during the history of NBS programs and are likely to continue to arise in the future (Annas, 1982; Currier, 2022; Faden et al., 1982; Ross, 2010). The factors that influence the outcomes of these debates may also change as technologies and social contexts evolve (Goldenberg and Sharp, 2012). For example, if new screening technologies raise concerns about the risks of screening (e.g., psychosocial effects; data privacy; false positives and misinterpretation; ethical, legal, and social issues), it could tip the balance in favor of more parental control over participation in screening. The public’s level of trust in science, medicine, and government could also influence how people view opt-out screening and the restrictions that should be placed upon these activities. Questions about who reaps the benefits and who incurs harms from newborn screening can also raise important considerations relevant to the conditions included on screening panels and the use of opt-out versus consented screening.

Testing Methods

Tests with the appropriate specificity and sensitivity are critical to the effectiveness of newborn screening as a public health intervention (Wilson and Jungner, 1968). A test with too many false positives burdens families

and health care systems with unnecessary stress and expense, whereas a test with too many false negatives undermines the value of universal screening and leads to missed or delayed diagnoses (Goldenberg et al., 2016). In addition, to be viable for newborn screening at a population level it is important for tests to be cost-effective and feasible to implement rapidly at scale using dried blood spots (Wilson and Jungner, 1968). Achieving and demonstrating all of these parameters requires substantial investments in basic research, test development and refinement, and pilot testing within NBS programs (Watson et al., 2022).

The tests used for newborn screening have evolved over time (Watson et al., 2022). Most tests used or proposed for newborn screening fall into two main categories: biochemical tests and molecular (or DNA-based) tests (Almannai et al., 2016; CDC, 2024c). Biochemical tests measure biomarkers contained in blood that are associated with specific health conditions. For example, the test for PKU measures the amount of the amino acid phenylalanine in a baby’s blood since children with PKU have elevated phenylalanine. Similarly, the test for cystic fibrosis measures the amount of the protein immunoreactive trypsinogen, which is typically elevated in babies with this condition (Minnesota Department of Health, 2022). Biochemical methods are used in both first-tier and second-tier testing (see Box 2-1 for definitions) (Almannai et al., 2016; CDC, 2024c).

Technology improvements in the 1990s enabled scientists to develop tests that measure multiple biomarkers with a single test, an approach called multiplexing. Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) is the main platform used for multiplex testing (Chace et al., 2003). The availability of MS/MS made it feasible for NBS programs to efficiently screen for more disorders, which ultimately led many states to substantially expand their screening panels between 1990 and 2008 (ACMG Newborn Screening Expert Group, 2005; Tarini, 2007). Other biochemical testing methods include high-performance liquid chromatography, liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, fluorometry, and isoelectric focusing (Minnesota Department of Health, 2022).

Molecular or nucleic acid-based tests identify genetic markers that are associated with health conditions. These genetic markers can be found in the DNA that each of us has within our cells (the genome), or they can be produced from various biological processes. The adoption of molecular tests for newborn screening is in its early stages. SCID was the first condition recommended for the RUSP that required the use of a molecular screening test, the TREC test (Van Der Spek et al., 2015). This test detects small DNA segments that are produced by certain immune cells, which are absent or low in infants with SCID, using a technique known as quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Chan and Puck, 2005). Other molecular testing methods include various other forms of PCR,

next-generation sequencing, and whole genome sequencing (Friedman et al., 2017).

Currently, NBS programs use nucleic acid-based methods to detect specific diseases with single gene or targeted genotyping, most often as a second-tier screen to achieve greater specificity when a first-tier biochemical test shows results outside of the expected range (Smith et al., 2020). These methods can also be used to provide just-in-time information to help clinicians prepare for their initial communication with families regarding NBS-positive results (Furnier et al., 2020). However, the potential capabilities represented by methods such as next-generation sequencing and whole genome sequencing extend far beyond this targeted use. If used as a first-tier strategy, genetic sequencing could theoretically be used to identify a much broader array of conditions than is currently included in newborn screening (Goldenberg and Sharp, 2012). For example, genome-based screens could enable easier identification of not only the types of conditions that have historically been included in NBS programs—serious, identifiable in newborns, and treatable if identified early—but also health conditions that may emerge later in life, conditions for which no treatments are available, and even other genetic information not directly related to health. This possibility raises questions about what types of information parents and the state should be able to obtain about newborns, how this information should be used and how it should be protected, and what additional benefits and harms may result (King and Smith, 2016).

Limited representation of different ancestral groups in genomic databases further complicates opportunities to expand the use of nucleic acid-based methods in newborn screening. Underrepresented ancestral backgrounds have higher rates of variants of uncertain significance,21 which could lead to misclassification of benign variants as pathogenic or missed diagnoses owing to an inability to recognize pathogenic variants (Rosamilia et al., 2024). Current second-tier testing for cystic fibrosis reveals these vulnerabilities as babies from underrepresented ancestral backgrounds are at a higher risk of receiving false-negative results and delays in intervention (McGarry et al., 2023). There are ongoing efforts to increase representation of different ancestral groups in genomic databases to ensure that all individuals receive access to the benefits of nucleic acid-based screening (All of Us Research Program Investigators, 2019; Fatumo et al., 2022; Wonkam

___________________

21 Variants, or genetic differences, are categorized as either pathogenic, likely pathogenic, uncertain significance, likely benign, and benign based on the ACMG guidelines. A variant is categorized as uncertain significance if there is insufficient or conflicting evidence to determine its clinical significance (Richards et al., 2015).

et al., 2022). See Chapter 5 for further discussion of the applications for nucleic acid-based methods in newborn screening with a focus on genomic sequencing.

Storage and Secondary Use of Blood Spots

The blood spots collected for newborn screening can be useful for various purposes after the initial screening tests are completed (Baby’s First Test, 2024a). Some of these potential uses are essential to the operation of NBS programs, others may benefit the infant or their family, while others may benefit society more broadly. Issues around the storage and subsequent use of blood spots after newborn screening raise important ethical, legal, and practical questions.

For families, blood spots from newborn screening can potentially be used to carry out subsequent testing (for example, to clarify an uncertain result or test for additional conditions) without requiring another blood draw (Baby’s First Test, 2024a).

Further, the use of leftover blood spots is instrumental for improving and ensuring the quality of NBS programs. These residual blood spots, which match the composition of the state’s population, are used by the NBS program for quality assurance and quality control purposes to continuously validate that the test methods used are accurate and reliable for each baby born (De Jesús et al., 2015; Texas Health and Human Services, 2024a,b).

Blood spots can also help advance biomedical research. Since a vast majority of infants participate in newborn screening, blood spot cards represent a large collection of biological samples that is broadly representative of the population. Blood spots can be used for environmental pollutant tracking and detection, genetic and epigenetic studies, biomarker detection, and drug monitoring (McClendon-Weary et al., 2020). Studying these samples can also lead to new insights about health and disease, including opportunities to identify, treat, and even prevent certain health conditions (Rothwell et al., 2019).

Like other aspects of newborn screening, there is no standard or universal practice for the storage and secondary use of blood spots across NBS programs; each state or territory establishes its own policies and practices (Lewis et al., 2011). Blood spots may be retained for a month or indefinitely; most states retain them for at least 6 months. They are typically stored in facilities managed by the laboratories that carry out NBS tests.22

___________________

22 See https://www.newsteps.org/data-resources/reports/dbs-retention-report (accessed September 26, 2024) for up-to-date information on the length of time programs retain dried blood spots associated with each program.