Newborn Screening in the United States: A Vision for Sustaining and Advancing Excellence (2025)

Chapter: 7 Envisioning the Future of Newborn Screening

7

Envisioning the Future of Newborn Screening

Newborn screening (NBS) as a public heath endeavor faces a complex array of needs, competing priorities, and viewpoints. NBS programs, federal agency partners, families, care providers, and many others must address longstanding challenges around the inclusion of conditions on screening panels, difficulties advancing the evidence base in the context of rare diseases, and the lack of awareness about public health newborn screening, while attending to issues on the horizon such as the appropriate use of genome-based screening technologies and continued legal and ethical scholarship around the consent and reuse of blood spot samples. A high-performing NBS system must exemplify excellence, and this chapter focuses on actions essential to not only sustain public health newborn screening but strengthen and prepare it for the future.

Taking a strategic, system-based approach to public health newborn screening is needed to navigate these challenges, bring together the many involved and affected parties, foster proactive recognition of shared challenges and issues, provide clarity and develop guidance, and work collaboratively with partners throughout the NBS system to develop solutions while respecting state and territorial autonomy. Drawing on the information and analyses provided throughout this report, the committee drew two overarching conclusions that informed its recommendations for preserving and strengthening newborn screening:

Overarching Conclusion 1: The next era of public health newborn screening needs to effectively use the resources and knowledge of state- and territorial-run public health programs and embrace opportunities for national coordination, strategy, and priority setting. Leadership and coordination at the national level

are needed to set priorities and maintain high performance while adapting to the longstanding and emerging challenges facing public health newborn screening.

Overarching Conclusion 2: Many perspectives—not only those of decision makers in the federal government—are essential to creating a unified vision for public health newborn screening and a road map to achieve it, but driving this vision forward will require federal leadership, accountability, and coordination.

RECOMMENDATIONS

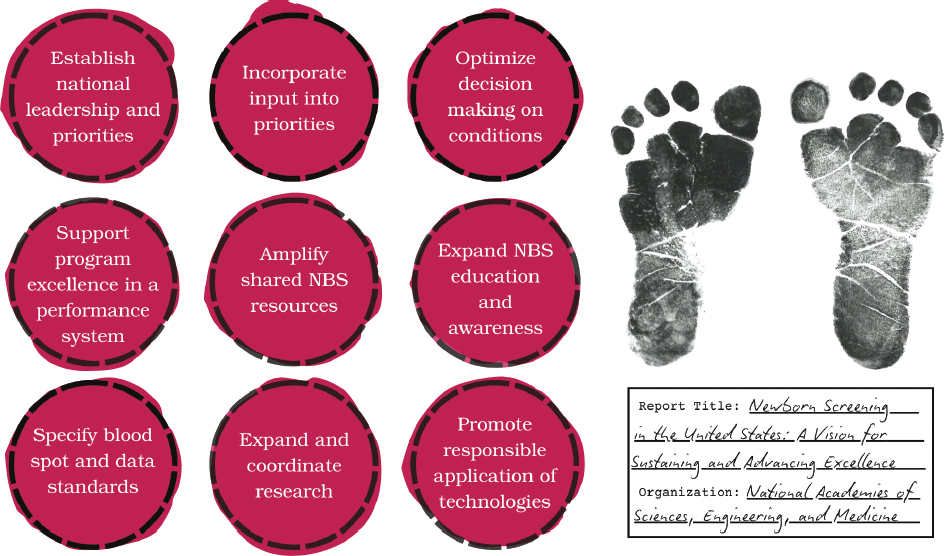

The nine recommendations below outline a path forward to navigate the tensions and pressures facing public health newborn screening in the United States while preserving and enhancing what is already a valuable and effective public health achievement (Figure 7-1). Collectively, these recommendations call for a more systematic and coordinated approach to align the NBS ecosystem around shared goals, build on the large array of efforts and programs already under way, and support newborn screening as it enters its next era.1

Establish National Vision, Coordination, and Leadership

Newborn screening, although fundamentally operated as a state- and territorial-run program, has been searching for a national vision for over

NOTE: NBS = newborn screening.

___________________

1 The report focuses on critical functions and actions to strengthen public health newborn screening for the future; descriptions of the roles and structures of federal and nonfederal activities relevant to newborn screening are current as of March 24, 2025.

two decades. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG), and others have called for increased national coordination and guidance since the late 1990s (AAP Newborn Screening Task Force, 2000; ACMG Newborn Screening Expert Group, 2006; Andrews et al., 2022). Among these reports, the 2006 ACMG report provided recommendations to move “toward a unified screening panel and system” to contend with a similar set of challenges as today. These recommendations served as the basis for establishing the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP)—a key piece of national guidance (ACMG Newborn Screening Expert Group, 2006).

Beyond the RUSP, five federal partners—the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)—each provide support, leadership, and guidance for different portions of the NBS landscape (see Chapter 2) (HHS, 2015). However, the totality of newborn screening encompasses processes and priorities that traverse public health, clinical care, and research. Parties across the broader NBS ecosystem have acknowledged that insufficient coordination and communication among federal agencies have previously hampered national data collection and decision making regarding the funding and implementation of newborn screening (Andrews et al., 2022). Greater national leadership can support that goal as well as the accomplishment of others, identified in Box 7-1.

Despite the efforts and progress of the federal agencies and others to bring a more unified vision to the complex landscape of public health newborn screening, the same challenges have persisted—and new ones have arisen. Box 7-2 provides examples of challenges that require national approaches to effectively address.

Recommendation 1: Establish national leadership and set priorities. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) should provide unified leadership, accountability, and coordination across government agencies, newborn screening (NBS) programs, and the broader NBS community.

- With input from partners (see Recommendation 2), HHS should establish a 10-year strategic plan to implement this report’s recommendations and begin to implement them.

- HHS should designate a mechanism with appropriate authority, accountability, and resources to facilitate realization of this plan.

Federal leadership, accountability, and coordination are needed to advance this coherent vision for public health newborn screening, enhancing

BOX 7-1

Goals to Be Addressed with Increased National Vision and Coordination

- Create more intentionality and coordination within an ecosystem that has been highly fragmented, particularly on the federal level, ultimately bringing more resources, authority, and capacity to the patchwork quilt of public health newborn screening (NBS).

- Align on a national vision and strategic plan by convening and drawing on perspectives from interested parties across the NBS ecosystem to ensure voices are heard.

- Develop a continuous performance improvement process, together with state and territorial NBS programs, to ensure the highest standards for public health newborn screening across all jurisdictions.

- Enable the collection of timely data to proactively inform policy decisions and act strategically within the entirety of the NBS ecosystem.

- Effectively allocate resources by maximizing their usefulness at a national and state level to address issues within the NBS ecosystem.

- Establish an accountability partner at the federal level for the achievement of goals within the NBS ecosystem.

- Serve as a communication locus for multiple stakeholders and rightsholders across the NBS ecosystem to enhance awareness of needs and opportunities and align efforts.

its impact without diminishing the unique roles and responsibilities of different parties. Although implemented through 56 state and territorial programs, public health newborn screening is buttressed by the contributions not only of federal agencies, but also of laboratory and clinical professional communities, patient groups, researchers from academia and industry, and others (see Chapter 2). All participants in this informal NBS ecosystem are dedicated to excellence within their sphere, but fragmentation and lack of

BOX 7-2

Selected Challenges in Public Health Newborn Screening Requiring National Coordination to Address

- Geographic disparities across state- and territorial-run newborn screening (NBS) programs

- Timely evidence generation to inform the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel

- Effective public communication concerning newborn screening

- Long-term follow-up infrastructure

- National recommended standards for the collection, retention, sharing, and use of newborn dried blood spots

coordination can permit goals and efforts to misalign. Newborn screening needs to embrace opportunities for coordination and priority setting while leveraging and respecting the autonomy and local expertise of state-run programs. Additional federal partners are essential to the success of newborn screening, and their involvement would enhance coordination and impact. For example, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is not a named federal NBS partner (HHS, 2015), but Medicaid covers NBS fees for approximately 40 percent of births annually (CMS, 2024). A coordinated approach, coupled with appropriate resources, authority, and accountability, can better align the efforts of the many partners involved in public health screening and enable each to understand their role in driving a strategic plan forward.

The national vision and coordination called for in this recommendation could be operationalized in different ways, while also recognizing and respecting the autonomy and unique roles of federal and state programs and agencies. Several options are described below.

Increased Interagency Coordination

Effectively using existing practices and authorities, federal agencies could maintain their respective spheres of influence and coordinate through interagency working groups with renewed purpose to develop strategic plans. Additional, relevant federal partners (e.g., CMS) can be brought into these working groups to strengthen coordination. However, such an approach would not permit whole-of-government coordination, nor would it provide a true accountability partner that can give due attention to the totality of public health newborn screening, avert issues related to diffusion of responsibility, and ensure progress on all items in the strategic plan.

Accountability Partner Embedded in an Agency

Another option would be to designate an accountability partner at one of the federal agencies, which could avoid issues related to diffused responsibility for achieving NBS-related goals. However, the five federal agencies that interact in newborn screening each contribute guidance and support (HRSA, CDC, NIH, FDA, and AHRQ) in different spheres, and the entirety of responsibilities would not fit neatly under any one agency.

Private–Public Strategic Council

The Department of Health and Human Services could create a public–private strategic council to establish a vision and set strategic priorities for public health newborn screening. However, executing that vision would be difficult with no oversight authority or budget. The ad hoc nature of

many advisory bodies also means that long-term sustainability to monitor progress in achieving priorities or to identify and address issues over time is limited and uncertain. An advisory body would also be limited in its ability to coordinate across the agencies and ensure the most effective and strategic use of resources.

Nonprofit Entity

A separate nonprofit entity could be created to convene partners to establish a national vision, and with appropriate funding, provide resources and supports. A nonprofit entity could excel at building partnerships across the public and private sectors to craft and enact innovative solutions. This model has been effective for the Fund for Public Health NYC, which was established as an independent nonprofit organization to connect the New York City Health Department to private-sector partners and the greater philanthropic communities.2 However, a primary purpose of a national mechanism would be to have appropriate authority and coordination across the federal agencies. Given that a nonprofit entity is situated outside of the federal government, opportunities to provide oversight and coordinate among the federal agencies would be limited.

Office, Point Person, or Advisor in HHS

An office, point person, or advisor could be designated in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to ensure coordination and a unified plan across the federal government and others, while recognizing and preserving the unique roles and responsibilities of agencies, state-run programs, and other stakeholders and rightsholders. The HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary of Health, which oversees HHS public health efforts, is a potential locus for such accountability.3 An office, point person, or advisor in HHS could coordinate across agencies, have convening power to solicit input from a wide-ranging set of stakeholders, establish national standards and guidance, and have a dedicated budget to follow through on strategic plans. This mechanism would require an investment of resources and might face scrutiny about government expansion. However, federal offices, point persons, and advisors are designated for many reasons, and often to advise on topics affecting vulnerable populations. Newborns are a large potentially at-risk population in the United States, with nearly 3.6 million babies screened each year, and an investment of resources could be merited to reduce morbidity and mortality across the population.

___________________

2 https://fphnyc.org/about/our-story/ (accessed December 12, 2024).

3 https://www.hhs.gov/ash/index.html (accessed December 18, 2024).

Combined Approaches

Some of the options outlined may be able to be combined to balance trade-offs and maximize benefit. For example, an office, point person, or advisor in HHS could be combined with a nonprofit entity. The position in HHS could provide oversight, accountability, and coordinate across federal agencies, and the nonprofit entity could function as the operational arm.

Incorporate Multistakeholder and Rightsholder Input on Newborn Screening

Creating a unified and strategic plan for newborn screening must draw in many perspectives—not only those of decision makers in the federal government. Representatives of the many groups personally and professionally affected by newborn screening must be engaged in identifying critical issues and potential solutions, developing a unified vision and strategic plan, and continually advancing and implementing this plan.

Recommendation 2: Incorporate multistakeholder and rightsholder input into newborn screening priorities.4 The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services should establish a multistakeholder/rightsholder advisory body to provide input to the national leadership identified in Recommendation 1. This advisory body should identify high-level, cross-agency, cross-state, and cross-system challenges; elevate potential solutions to those challenges; inform the development of a strategic plan; and monitor and advise on progress in its implementation. The advisory body should engage wide-ranging expertise and experiences to inform the strategic plan and enable all partners to understand their role in driving it forward.

Currently, the discretionary HHS Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children (ACHDNC) provides recommendations to the HHS secretary on newborn and childhood screening, including the appropriate application of tests, technologies, policies, guidelines, and standards to effectively reduce morbidity and mortality in newborns and children with serious disorders (HRSA, 2024b). ACHDNC might seem like a natural fit to take on such a strategic advising task. However, as currently designed, ACHDNC would not

___________________

4 The term rightsholder is incorporated to recognize use of this term among Native American and Indigenous communities and to reflect their distinct legal and political contexts.

be suitable to take on this function for two reasons. First, although the scope of ACHDNC’s mandate is theoretically broad, the committee’s attention is primarily directed toward reviewing conditions for potential addition to the RUSP. This emphasis is responsive to the importance of evidence-based decision making for adding conditions to the RUSP, but it limits ACHDNC’s capacity to focus on overarching strategy. Second, the current membership of ACHDNC primarily represents federal agencies, state-run programs with a focus on laboratory expertise, and medical professionals.5 The current ACHDNC does not comprise the full breadth of expertise and experiences that would be necessary for this more strategic advisory mission.

The multistakeholder/rightsholder advisory body called for in Recommendation 2 would focus on high-level, cross-agency, cross-state, and cross-system challenges. Other mechanisms or approaches are needed to address processes associated with the RUSP (see Recommendation 3). The multistakeholder/rightsholder advisory body could be established in different ways, including as a formal federal advisory committee or through other federal or nonfederal convening mechanisms. Regardless of how it might be implemented, a wide range of expertise and perspectives is essential to the success of public health newborn screening and the advisory body would need to include

- members among state/territorial NBS program directors, laboratory experts, and follow-up experts;

- prenatal and birth care providers;

- health care providers such as genetic counselors, pediatricians, and disease specialists;

- members reflecting family and rare disease community organizations and perspectives;

- the multiple federal agencies involved;

- philanthropic organizations active in this area; and

- the private sector.

Newborn screening involves a complex nexus of federal, state, tribal, and private rights and responsibilities. Additional conversations are needed with tribal nations and leaders to understand these intersecting rights and authorities, involve tribal communities in the national vision for newborn screening, and ensure that priorities and solutions meet the needs of Indigenous communities.

___________________

5 The current membership roster of ACHNDC is available at https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/heritable-disorders/achdnc-membership-roster.pdf (accessed December 18, 2024). Public health, medical, or community advocacy organizations may also serve as nonvoting organizational representatives.

Optimizing the RUSP

Prior to the creation of the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel in 2010, there was no national guidance on which conditions to include in state NBS panels, leading to substantial variation in disorders screened from state to state. Although the RUSP is not a mandate, it has helped harmonize the landscape of NBS programs and emphasized the importance and role of rigorous evidence review when making decisions about conditions to include in population-wide screening (See Chapter 2).

Overarching Conclusion 3: The Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) remains an important source of evidence-based guidance on which conditions to include in state panels for newborn screening (NBS). Striving for alignment with the RUSP promotes consistency across NBS programs and provides infants born across the United States with an equal opportunity to be screened for these conditions.

However, the process for evaluating or incorporating new conditions on the RUSP is long and burdensome (Andrews et al., 2022; Armstrong, 2024; HRSA, 2024a; Susanna Haas Lyons Engagement Consulting, 2024). This protracted time line is a consequence of multiple inputs spanning evidence generation, nomination, evidence review, decision making in the face of limited and incomplete data, and other associated factors. There are no simple answers to the RUSP. A complete reimagining of the RUSP review process risks exhausting already resource-constrained public health and clinical care systems; however, the process as it currently exists is untenable, burdensome, and frustrating to many.

Addition of a condition to the RUSP also does not translate into uniform screening implementation, or even consideration, across states and territories. Instead, advocates and others must navigate state-by-state processes for adding conditions to NBS panels. Every state or territory needs a mechanism to ensure the systematic consideration of conditions added to the RUSP in a timely manner, even if screening is not ultimately implemented.

Recommendation 3: Optimize decision making on conditions included in newborn screening. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and state and territorial newborn screening (NBS) programs should optimize the process of considering conditions in public health newborn screening.

- HHS leadership should designate a focused committee or mechanism to provide advice on the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP), composed of appropriate experts and distinct from the strategic advisory body in Recommendation 2. In addition to advising on nominated

- conditions, this committee should (1) proactively assess which conditions could meet criteria for inclusion on the RUSP; (2) identify specific gaps in evidence necessary for RUSP decision making for conditions identified in this assessment and highlight what strategic research is needed (see Recommendation 8); (3) periodically reassess evidence and consider whether RUSP removal is warranted for any condition based on knowledge gained from its implementation in public health newborn screening.

- HHS leadership should expand the scientific and technical capacity for reviewing evidence for conditions under consideration for addition to the RUSP, including exploring the applicability of rapid review mechanisms.

- State and territorial NBS programs should have a mechanism to consider implementation of RUSP conditions within a designated time line.

This recommendation could be achieved by focusing and enhancing the ACHDNC’s current mission. In the near term, action is needed to streamline the evidence generation and review processes for the RUSP while maintaining sufficient scientific and technical rigor. A major first step is commissioning a landscaping analysis to understand which conditions could fit inclusion criteria for public health newborn screening, facilitate proactive decision making, and identify gaps in research evidence necessary to inform decision making for RUSP inclusion. Such gaps could inform conditions to include in NBS pilot studies or other research endeavors. This analysis would be critical to enable strategic research investment and timely, evidence-based decision making. Comparisons of gene-condition lists across multiple newborn sequencing research programs focused on serious, urgent, and treatable conditions may inform this work (Downie et al., 2024; Minten et al., 2024). For example, a comparison across 27 programs identified 74 genes included by over 80% of programs (Minten et al., 2024). Of those genes, 58 are associated with conditions already on the RUSP, but other associated conditions could provide a starting point for a landscaping analysis.

In the face of genomic technologies and ongoing therapeutic innovation for rare diseases, groundwork must also be laid for a future where an increased number of conditions that align with the public health goals of newborn screening could be incorporated in screening. Pilot testing the feasibility of adopting more rapid review mechanisms used by consented research studies exploring DNA-based screening in newborns is one avenue to explore. The processes used for condition review and inclusion determinations for consented research studies using genomic sequencing

in newborns, such as NC Nexus or Early Check, may be informative as these studies include hundreds of conditions on screening panels (Cope et al., 2024; Milko et al., 2019). However, their primary focus is on whether conditions meet inclusion criteria of being serious, urgent, and actionable; review of implementation data is not included. One study comparing rapid review versus full systematic review mechanisms to assess newborn screening for a single condition found that rapid reviews may be appropriate tools if safeguards are in place (Taylor-Phillips et al., 2017).

Exploring the implications of adopting or adapting rapid review mechanisms for the RUSP may be one first step toward reenvisioning the RUSP process, though careful attention will need to be paid to context as RUSP decisions inform universal public health newborn screening rather than consented research pilots. The process for adding conditions to the RUSP will need to be reexamined periodically, in light of further developments in screening technologies and in the evidence base for diseases that could potentially be included, as well as in the context of the enhanced public health NBS system recommended in this report.

Other actions to enhance the RUSP process include increasing the number of scientific and technical experts involved in evidence review and designating a dedicated or specialized committee or mechanism whose focus is to provide advice on the RUSP. Evidence evaluation for RUSP decision making needs to focus on relevant scientific, clinical, and technical aspects of the condition; its effects and treatments; and its implementation in public health screening. Issues related to individual NBS program operational feasibility are better addressed through supports to state-level programs (see Recommendations 4 and 5).

State and territorial NBS programs may need to work with their legislatures, public health departments, and other involved communities to identify and implement a mechanism to assess conditions as they are added to the RUSP. One mechanism could include a process and time line for considering a newly added RUSP condition by their state’s advisory committee (e.g., Washington State).6 Another would be for a state or territory to enact RUSP alignment laws, which require NBS programs to implement screening for RUSP conditions within a certain time frame. While some states already have these mechanisms in place, others do not.7 When states or territories do not implement a RUSP condition, some may choose to inform parents of other mechanisms parents could pursue

___________________

6 See https://sboh.wa.gov/sites/default/files/2024-11/Tab09a_Cover%20Memo_NBS%20TAC%20Review.pdf (accessed March 6, 2025).

7 The National Organization for Rare Disorders documents policies for considering and/or implementing RUSP disorders across the United States. See https://rarediseases.org/policy-issues/newborn-screening/#_ftn3 (accessed March 7, 2025) and select appendices to see detailed information about each state.

for screening (e.g., private laboratory testing). Although mechanisms for timely consideration or implementation of RUSP conditions are needed, the successful implementation of high-quality screening across programs will require more robust systems of support, described below.

Establish a System to Support NBS Program Excellence

Public health newborn screening is implemented through 56 NBS programs, which operate independently from each other under a wide range of operational and funding structures and within the different contexts of their local health care systems. Variation in the practice of newborn screening across state- and territorial-run programs is inevitable given these circumstances and can enable programs to address their specific circumstances and populations. However, strengthening the network of NBS programs requires addressing detrimental variability that arises from insufficient resources or support and that can negatively affect health outcomes. Ensuring that all 56 programs have what they need to achieve excellent performance in their essential functions requires more systematic data collection and analysis and more strategic alignment of financial and nonfinancial supports and incentives (see Chapter 4).

Enhanced data collection and analysis efforts can build on the foundation initiated through current, grant-based efforts that rely on voluntary submission from NBS programs, such as the Association of Public Health Laboratories’ (APHL’s) Newborn Screening Technical assistance and Evaluation Program (NewSTEPs) data repository and resource center, supported by a grant from HRSA.8 Clarity on common metrics and commitments to collect and use data systematically is needed from NBS programs and federal agencies.

Recommendation 4: Support newborn screening (NBS) program excellence in a performance system. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) leadership (Recommendation 1) and state- and territorial-run NBS program directors should partner to establish a universal performance improvement system. Data collected should enable each program to assess its laboratory and follow-up performance, benchmark with peers, and iteratively improve its processes. To accomplish this the following needs to occur:

- HHS should incentivize participation from all programs.

- HHS should collaborate with state and territorial NBS program directors to identify a common set of performance

___________________

8 See https://www.newsteps.org/ (accessed December 18, 2024).

- metrics all states will collect to monitor and improve laboratory and follow-up performance.

- State/territorial-run NBS programs should agree to participate and commit to using collected data to close gaps and pursue excellence.

- HHS should provide responsive financial investment and technical assistance based on performance assessment.

Several approaches could be taken to establish a universal NBS performance excellence and improvement system. One option could be to augment the existing NewSTEPs or envisioned Enhancing Data-driven Disease Detection in Newborns (ED3N) resources.9 Currently, data collected through NewSTEPs may not target the most useful metrics, have limited or partial participation from state and territorial NBS programs, and are not analyzed and used in a holistic way to inform responsive or strategic decisions. CDC’s ED3N platform, currently in development, aims to serve as a voluntary collection and analysis platform for biochemical and molecular testing data to assist NBS partners to improve screening performance. Potential ED3N modules for clinical or follow-up data analysis have also been envisioned (see Chapter 4).

Strengthening, expanding, and systematizing NewSTEPs and/or ED3N infrastructure to serve as a universal NBS performance improvement system would require coordinated efforts with federal and state agencies, programs, and others to identify and agree on a common set of key performance metrics, incentives for programs to participate, and responsive funding and technical assistance based on performance. Other potential approaches could include establishing an expanded federal cooperative assistance program (such as the CDC Epidemiology and Lab Capacity Program) or other forms of private or nonprofit organization that focus on performance excellence (such as the California Perinatal and Maternal Quality Care Collaboratives) (see Chapter 4). For the approach selected, the HHS leadership mechanism established in Recommendation 1 would need to provide funding (both to support the system itself and to incentivize state and territorial program participation), oversight, guidance, and accountability.

Measuring, documenting and understanding the longer-term effects of newborn screening on the care, services, and health outcomes of infants diagnosed with a screened condition is important for analyzing how well newborn screening programs function and for making decisions about their future. Designing and implementing a mechanism to collect and analyze such long-term follow-up data after newborn

___________________

9 https://www.cdc.gov/newborn-screening/php/about/ed3n-project.html (accessed March 4, 2025).

screening remains challenging because it entails information across state public health agencies, medical records housed in varied care settings, public and private insurance records, and other data sources. A universal and strategic NBS performance improvement system might not, at least initially, include metrics related to long-term follow-up. Although long-term follow-up data are critical to understand the public health effect of newborn screening and to strengthen the NBS system, collection of such information requires clinical health and public health partnerships, health information technology infrastructures, and other capacities that are outside the scope and ability of most state and territorial NBS programs. See Chapter 5 for options to address long-term follow-up data collection.

Amplify Program Excellence Through Shared Resources

NBS programs vary in their resources, expertise, and capacities for advanced technical analysis of newborn blood spots, development and implementation of new screening assays, establishing connections with specialized genetic counseling and clinical care communities for screened conditions, and other factors. As described in Chapter 4, available federal resources are often ad hoc or grant based, requiring NBS program staff to identify challenges, locate prospective resources, and prepare competitive grant applications. While helpful, this approach risks exacerbating existing disparities among programs, in which already strong and well-resourced NBS programs are better positioned to apply. Informal “ask a colleague” requests through community forums such as the APHL NewSTEPs discussion board and via personal networks and contacts, as well as formal, individual state-to-state agreements, are other approaches used to supplement NBS programs’ capacities.

All programs must achieve and maintain excellence in the core functions necessary to deliver on the promise of universal, at-birth newborn screening. Strengthening the network of 56 NBS programs will require each to have access to the range of resources, capacities, and expertise needed to provide an excellent public health service to all babies. Mechanisms to facilitate sharing across NBS programs will also help maximize and support more efficient use of scarce resources and expertise, such as for capabilities for advanced technical analysis and genetic counseling expertise.

Recommendation 5: Amplify newborn screening (NBS) program excellence through shared resources. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) leadership (Recommendation 1) should foster NBS programs’ ability to

efficiently access and use specialized resources and expertise. To achieve this, HHS should survey NBS program directors to identify each program’s capacities, strengths, and sources of specialized expertise in both laboratory and follow-up performance; assess this resulting landscape; and establish infrastructure for more systematic and efficient use of shared resources among programs.

A variety of mechanisms and approaches could be used to implement this recommendation. One useful first step is identifying the landscape of strengths, specialized resources, and expertise each NBS program provides, along with major gaps or needs. HHS could develop a centralized repository of such information, establish or designate resource centers to facilitate connections between programs, and provide additional or targeted federal support to enable programs to share these assets and skills. Which resource-sharing agreements would need to be established among states, the benefits and burdens that would pose, and the ability for national templates and federal support to facilitate that process would need to be better understood.

More formalized centers for expertise could also be established at several NBS programs to provide direct services and peer mentorship. Establishing or designating centers for specialized expertise would help provide access to important capacities, although the full implications would need to be further explored as this approach may direct federal resources toward the already strongest programs.

Parents and Providers as Partners in the NBS System

Despite longstanding calls for increased NBS education, particularly during the prenatal period (ACOG Committee on Genetics, 2019; Botkin et al., 2016; Davis et al., 2006; Therrell et al., 2011), current efforts are not effectively engaging all families (see Chapter 4). Many parents are unaware of newborn screening until the moment it occurs, and others do not recall that their infant ever received newborn screening (Campbell and Ross, 2004; Kusyk et al., 2013; Susanna Haas Lyons Engagement Consulting, 2024). Parents and caregivers need more systematic information about the purpose of newborn blood spot screening, when and how it will happen, what to expect after blood spot collection, and parental options—both concerning screening and the retention and reuse of the residual dried blood spot. Education and engagement can take varied forms including printed materials (e.g., pamphlets and posters), electronic resources (e.g., videos, images, and websites), and conversations with care providers and educators. Many NBS educational resources exist,

developed by family support and advocacy organizations, professional associations, government agencies, and others.10 Providers must have sufficient knowledge about the basic practices of newborn screening, how to routinely integrate and disseminate resources on newborn screening into care, and the fundamentals of genetics so they are prepared to engage with patients responsibly about newborn screening.

Recommendation 6: Expand public and professional newborn screening (NBS) education and awareness. Engagement with pregnant individuals, parents, and caregivers should occur at multiple points during the perinatal period. This education should start in the prenatal period and cover the purpose of newborn screening, when and how it will happen, what to expect after blood spot collection, parental options, and communication of the infant’s results.

- All professional associations involved in perinatal and infant care should issue recommendations for communicating about newborn screening with pregnant patients, parents, and/or caregivers and support accurate communication through professional education.

- The multistakeholder/rightsholder advisory body described in Recommendation 2 should work with relevant professional societies, patient/family organizations, and experts in effective public communication to design goals and communication approaches that can be adapted to local contexts, drawing on existing materials and research.

Reaching as many parents and caregivers as possible will require disseminating resources at multiple points by multiple actors using a “no wrong door” approach. Key opportunities for communication include prenatal care and prenatal classes, following birth at the point of screening, and during the newborn period as part of pediatric care. Relevant professional societies that must participate in NBS education include, but are not limited to, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nurses; American Association of Birth Centers; American College of Nurse-Midwives; American Academy

___________________

10 Links to multiple resources and materials on newborn screening are available through the HRSA’s Newborn Screening Resources page (https://newbornscreening.hrsa.gov/about-newborn-screening/newborn-screening-resources; accessed November 27, 2024), through Baby’s First Test (https://www.babysfirsttest.org/newborn-screening/resources; accessed November 27, 2024), through Expecting Health (https://expectinghealth.org/programs/newborn-screening-family-education-program; accessed February 4, 2025), and through multiple other sources.

of Pediatrics; American Academy of Family Physicians; National Association of Family Nurse Practitioners; National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners; Society of Pediatric Nurses; and others. Clarifying professional recommendations and clinical practice guidelines for NBS education during the perinatal period, as well as the coding and reimbursement of such services, may be necessary to help support and facilitate widespread adoption.

Specifying Standards for the Retention and Use of Dried Blood Spots

After newborn screening, a portion of the dried blood spot is usually left over. These residual dried blood spots have many important uses that are essential to the core purpose of public health newborn screening, including retesting or second-tier testing if needed, as well as quality control, assurance, and improvement efforts. Residual dried blood spots can also be used for other purposes, including for research or forensics (see Chapter 4). Despite these important potential uses, there are few consistent policies at the federal, state, tribal,11 or laboratory level setting rules or expectations for NBS dried blood spot retention and use, along with varying parental disclosure or consent policies about what will happen to their child’s specimen (Botkin et al., 2013; Ram, 2022).

Stakeholders and rightsholders throughout the NBS system have strong views on the appropriate uses and limitations of these specimens. Concerns about storage and reuse are rising and have only been exacerbated by instances of law enforcement access for the purposes of prosecution. Several court cases have challenged the retention and secondary use of these blood spots as federally unconstitutional under the Fourth Amendment (prohibiting unreasonable searches and seizures) and the Fourteenth Amendment (prohibiting the deprivation of liberty without due process), leading to the destruction of millions of blood spots. Developing clear state standards and protections are necessary to act in trustworthy ways and avoid federal constitutional challenge.

Recommendation 7: Specify standards for the retention, sharing, and use of newborn dried blood spots and derived data.

-

State legislatures should set law and policy for the retention, sharing, and use of newborn dried blood spots and any derived data. These policies and laws should do the following:

- Protect the retention of newborn screening (NBS)

___________________

11 Additional clarifications may be needed to understand legal authorities over newborn dried blood spots collected in tribal health care settings, jurisdiction of tribal data sovereignty, and applicable state laws governing NBS programs.

-

- dried blood spots for at least a limited period for primary public health screening goals including, but not limited to, retesting samples, quality assessment, and quality improvement.

- Set transparent practices for the retention, sharing, and use of dried blood spots for purposes other than those described above, including research.

- Allow parents the option to request the destruction of their child’s specimen after the limited time period of retention for primary public health screening goals, and allow the dried blood spot contributor the option to request the destruction of their own specimen when they reach the age of 18.

- Prohibit the sharing or use of NBS dried blood spots and derived data to conduct criminal, civil, or administrative investigations and/or impose criminal, civil, or administrative liability on the NBS contributor or blood relatives.

- The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) leadership (Recommendation 1) should provide national guidance or recommendations on these standards.

- HHS leadership and state legislatures should establish additional guidance if NBS programs begin implementing genomic sequencing methods that increase the generation and identifiability of sensitive data.

Courts have pointed to the duration of retention as a critical component of assessing whether the government collection of NBS dried blood spots and associated data is “narrowly tailored” to achieve the public health goals of newborn screening.12 Courts have also established that written consent for research with dried blood spots collected for public health newborn screening is necessary.13 However, opt-in approaches for research with residual dried blood spots have been criticized as being too burdensome for hospitals to implement. Concerns arise that hospitals will not ask for consent and therefore limit the supply of dried blood spots for research, even from parents that would otherwise consent (Botkin et al., 2013; Drabiak-Syed, 2011). For example, the comprehensive opt-in approach implemented by the Michigan BioTrust for Health resulted in a reduction in dried blood spots available for research but did not result in an increase in parental refusal for public health newborn screening

___________________

12 Kanuszewski v. Mich. HHS, 927 F. 3d 396.

13 Kanuszewski v. Mich. HHS, 684 F. Supp. 3d 637, 660 (2023).

itself. The program considered the consequences of this approach, which favors increased transparency, a reasonable public health trade-off (Duquette et al., 2011, 2012; Langbo et al., 2013). Balancing these feasibility, ethical, and legal concerns will require national guidance. Further discussions may be needed as the legal landscape continues to evolve.

National guidance could also include recommendations for how to securely and effectively store NBS dried blood spots, including practices to preserve samples for future use, secure facilities, and label samples.

Strengthening the NBS Research Enterprise

NBS policy and programmatic decisions must be guided by a robust review of the available evidence (see Chapter 5). Research that informs these decisions falls into four major categories:

- defining conditions to guide screening, diagnosis, and treatment;

- developing laboratory testing and applying emerging technologies;

- understanding ethical, legal, and social issues; and

- investigating public health practice, feasibility, and impacts.

However, robust and timely evidence generation in these areas is complicated by many factors, including the rarity of conditions considered for inclusion in newborn screening and the lack of coordination limiting the ability to draw clear conclusions (Bailey, 2022; Halley et al., 2022; Largent and Pearson, 2012). Furthermore, research funding is not consistently strategic and responsive to pressing needs for public health newborn screening, diminishing the effect of these investments. Therefore, a national plan with associated research infrastructure is needed to ensure that research informing public health newborn screening provides timely evidence to address priorities.

Recommendation 8: Expand and coordinate research to inform newborn screening (NBS) policy and practice. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services should establish an NBS research network with centers that address system-level research priorities in a coordinated and nimble manner. This network of research centers should operate in partnership with state/territorial NBS public health programs as appropriate to carry out research in the following areas:

- Defining diseases to guide screening, diagnosis, and treatment.

- Developing laboratory tests and applying emerging technologies.

- Understanding ethical, legal, and social issues.

- Investigating public health practice, feasibility, and impact.

Centers in this NBS research network should develop their own research questions and work together to generate evidence to address high-priority issues in the areas above. Such studies will help inform analyses and policy decisions affecting the delivery, quality, cost, and health outcomes associated with public health newborn screening. The NBS research network should involve patient advocacy groups in research design to facilitate bidirectional communication about perspectives, needs, and interests. This recommendation is not meant to replace all federally funded investigator-initiated NBS research, which is important to promote creativity and elevate research questions identified among investigators throughout the community.

Investing more systematically and strategically in NBS research would also advance research on rare diseases. NBS research and rare disease research have unique but complementary scopes (see discussion in Chapter 5). Because population-based screening is an important approach for understanding the full phenotypic spectrum for rare diseases and identifying presymptomatic individuals, many are eager for their condition of interest to be added to public health newborn screening. However, NBS research must not be conflated with public health newborn screening, which cannot be used for research purposes. Instead, NBS research provides an important avenue to understand rare diseases and inform the development of treatments and other related priorities. This investment toward NBS research would thus complement but have a distinct focus from other initiatives aimed at advancing rare disease therapies, such as the NIH-funded Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network and FDA’s recent establishment of the Rare Disease Innovation Hub.14

Applying Technology to Newborn Screening

Decisions around the application of screening technologies require the same level of scrutiny, analysis, and alignment with vision and ethical principles as other decisions that affect the practice of newborn screening. Recent advances in genomic sequencing technology have attracted substantial research investment to determine the usefulness and acceptability of genomic sequencing in newborns (Minear et al., 2022). DNA-based tools, including sequencing of single genes, are

___________________

14 See https://www.rarediseasesnetwork.org/ and https://www.fda.gov/industry/medical-products-rare-diseases-and-conditions/fda-rare-disease-innovation-hub (both accessed January 16, 2025).

already used in limited capacities across NBS programs (Furnier et al., 2020). Genomic sequencing could provide the opportunity to screen for all genetic conditions that meet criteria for inclusion on NBS panels using a single platform as a first step. However, many questions remain about how it could be implemented responsibly, whether it is acceptable to the public, what protections might be needed, how to ensure equitable access and accurate interpretation across ancestral populations, whether it is economically and practically feasible, and more (see Chapter 5). Key questions can guide the investments and activities of funders and investigators across government, nonprofit organizations, and industry.

Recommendation 9: Promote the responsible application of technologies to newborn screening (NBS). Funders and investigators of feasibility studies should address the following key scientific, technical, ethical, and implementation questions before considering genomic sequencing for public health newborn screening:

- What sequence should be generated, what sequence/variants should be analyzed and interpreted, and what results should be returned?

- What strategies are necessary to ensure the accuracy of variant interpretation across ancestral populations?

- What are public attitudes concerning the application of genomic sequencing into public health newborn screening as a first-tier screening tool?

- What data should be stored after screening, if any, and how will the privacy of genomic data be protected given its risk of reidentification?

- Is genomic sequencing as a first-tier screening methodology cost-effective?

- What funding, resource sharing, and/or distributed system of clinical expertise would be necessary and effective to support employing population-based genomic sequencing as a first-tier tool across NBS programs?

Near-Term Actions to Make Progress Toward This Vision

Accomplishing the nine recommendations presented above entails a long-term vision. However, progress can be made now through multiple actions to advance elements of these recommendations and strengthen public health newborn screening. Box 7-3 highlights examples of achievable starting points.

BOX 7-3

Selected Examples of Starting Points and Near-Term Actions

- Identify each newborn screening (NBS) program’s capacities, strengths, and sources of specialized expertise in laboratory operations, follow-up, education, and other areas (state and territorial NBS programs, federal agency partners, and information coordination and repository partners such as the Association of Public Health Laboratories).

- Connect NBS records to vital records that record births. This helps understand whether every baby received newborn screening and informs analysis (NBS programs, working with their state legislatures and public health departments as needed).

- Implement electronic messaging so NBS programs can both receive and transmit electronic messages. This enables rapid communication between NBS programs and health care providers and may support more timely connection to clinical care (NBS programs, working with their state legislatures and public health departments as needed).

- Begin identifying core metrics to understand whether screening assays perform differently among babies from different ancestral backgrounds and to understand whether all at-risk babies received follow-up and a clinical care handoff (NBS programs, working with other state offices, primary and specialty care providers, electronic health record vendors, and other partners).

- Commit to providing existing NBS communication materials (for example, a simple brochure) and engaging in initial conversations about newborn screening with all prospective parents during prenatal visits (prenatal care provider associations, care providers, NBS programs, and NBS education partners such as patient and family organizations).

- Understand each state’s current requirements for the collection, retention, sharing, and use of newborn dried blood spots and derived data, and enact protections against law enforcement use of NBS blood spots if not already prohibited (NBS programs, working with other state offices as needed).

- Index newborn screening in the Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization system to provide greater clarity on the scope and range of investigator-initiated research funding addressing NBS (NIH).

- Commission the analysis of conditions to determine which meet inclusion criteria for newborn screening and to identify evidence gaps to guide research (HHS).

- Begin aligning partners to define the goals of a national system for the collection and analysis of long-term follow-up data, including the key questions to be addressed from the resulting data analysis and the associated outcomes to track, such as survival.

REFERENCES

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics) Newborn Screening Task Force. 2000. Serving the family from birth to the medical home. A report from the Newborn Screening Task Force convened in Washington, DC, May 10-11, 1999. Pediatrics 106(2 Pt 2):383-427.

ACMG (American College of Medical Genetics) Newborn Screening Expert Group. 2006. Newborn screening: Toward a uniform screening panel and system. Genetics in Medicine Suppl 1:1S-252S.

ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) Committee on Genetics. 2019. Newborn screening and the role of the obstetrician-gynecologist. ACOG Committee Opinion Number 778. Obstetrics and Gynecology 133(5):e357-e361.

Andrews, S. M., K. A. Porter, D. B. Bailey, Jr., and H. L. Peay. 2022. Preparing newborn screening for the future: A collaborative stakeholder engagement exploring challenges and opportunities to modernizing the newborn screening system. BMC Pediatrics 22(1):90.

Armstrong, N. 2024. Advocacy perspectives on adding new diseases: Experiences with developing a nomination package. Presented at Committee on Newborn Screening: Current Landscape and Future Directions Meeting 2. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42052_03-2024_newborn-screening-current-landscape-and-future-directions-meeting-2 (accessed January 23, 2025).

Bailey, D. B., Jr. 2022. A window of opportunity for newborn screening. Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy 26(3):253-261.

Botkin, J. R., A. J. Goldenberg, E. Rothwell, R. A. Anderson, and M. H. Lewis. 2013. Retention and research use of residual newborn screening bloodspots. Pediatrics 131(1):120-127.

Botkin, J. R., E. Rothwell, R. A. Anderson, N. C. Rose, S. M. Dolan, M. Kuppermann, L. A. Stark, A. Goldenberg, and B. Wong. 2016. Prenatal education of parents about newborn screening and residual dried blood spots: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatrics 170(6):543-549.

Campbell, E. D., and L. F. Ross. 2004. Incorporating newborn screening into prenatal care. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 190(4):876-877.

CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services). 2024. 2024 Medicaid & CHIP beneficiaries at a glance: Maternal health. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/downloads/2024-maternal-health-at-a-glance.pdf (accessed February 19, 2025).

Cope, H. L., L. V. Milko, E. R. Jalazo, B. G. Crissman, A. K. M. Foreman, B. C. Powell, N. A. DeJong, J. E. Hunter, B. L. Boyea, A. N. Forsythe, A. C. Wheeler, R. S. Zimmerman, S. F. Suchy, A. Begtrup, K. G. Langley, K. G. Monaghan, C. Kraczkowski, K. S. Hruska, P. Kruszka, K. S. Kucera, J. Berg, C. M. Powell, and H. L. Peay. 2024. A systematic framework for selecting gene-condition pairs for inclusion in newborn sequencing panels: Early Check implementation. Genetics in Medicine 26(12):101290.

Davis, T. C., S. G. Humiston, C. L. Arnold, J. A. Bocchini, Jr., P. F. Bass 3rd, E. M. Kennen, A. Bocchini, P. Kyler, and M. Lloyd-Puryear. 2006. Recommendations for effective newborn screening communication: Results of focus groups with parents, providers, and experts. Pediatrics 117(5 Pt 2):S326-S340.

Downie, L., S. E. Bouffler, D. J. Amor, J. Christodoulou, A. Yeung, A. E. Horton, I. Macciocca, A. D. Archibald, M. Wall, J. Caruana, S. Lunke, and Z. Stark. 2024. Gene selection for genomic newborn screening: Moving toward consensus? Genetics in Medicine 26(5):101077.

Drabiak-Syed, K. 2011. Legal regulation of banking newborn blood spots for research: How Bearder and Beleno resolved the question of consent. Houston Journal of Health Law and Policy 11:1-46.

Duquette, D., A. P. Rafferty, C. Fussman, J. Gehring, S. Meyer, and J. Bach. 2011. Public support for the use of newborn screening dried blood spots in health research. Public Health Genomics 14(3):143-152.

Duquette, D., C. Langbo, J. Bach, and M. Kleyn. 2012. Michigan BioTrust for Health: Public support for using residual dried blood spot samples for health research. Public Health Genomics 15(3-4):146-155.

Furnier, S. M., M. S. Durkin, and M. W. Baker. 2020. Translating molecular technologies into routine newborn screening practice. International Journal of Neonatal Screening 6(4):80.

Halley, M. C., H. S. Smith, E. A. Ashley, A. J. Goldenberg, and H. K. Tabor. 2022. A call for an integrated approach to improve efficiency, equity and sustainability in rare disease research in the United States. Nature 54(3):219-222.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2015. Report to Congress: Newborn screening activities. https://mchb.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/mchb/programs-impact/nbs-report.pdf (accessed February 21, 2025).

HRSA (Health Resources and Services Administration). 2024a. Nominate a condition. https://www.hrsa.gov/advisory-committees/heritable-disorders/rusp/nominate (accessed December 18, 2024).

HRSA. 2024b. Charter: Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/heritable-disorders/achdnc-charter.pdf (accessed December 18, 2024).

Kusyk, D., K. Acharya, K. Garvey, and L. F. Ross. 2013. A pilot study to evaluate awareness of and attitudes about prenatal and neonatal genetic testing in postpartum African American women. Journal of the National Medical Association 105(1):85-91.

Langbo, C., J. Bach, M. Kleyn, and F. P. Downes. 2013. From newborn screening to population health research: Implementation of the Michigan BioTrust for Health. Public Health Reports 128(5):377-384.

Largent, E. A., and S. D. Pearson. 2012. Which orphans will find a home? The rule of rescue in resource allocation for rare diseases. Hastings Center Report 42(1):27-34.

Milko, L. V., J. M. O’Daniel, D. M. DeCristo, S. B. Crowley, A. K. M. Foreman, K. E. Wallace, L. F. Mollison, N. T. Strande, Z. S. Girnary, L. J. Boshe, A. S. Aylsworth, M. Gucsavas-Calikoglu, D. M. Frazier, N. L. Vora, M. I. Roche, B. C. Powell, C. M. Powell, and J. S. Berg. 2019. An age-based framework for evaluating genome-scale sequencing results in newborn screening. Journal of Pediatrics 209:68-76.

Minear, M. A., M. N. Phillips, A. Kau, and M. A. Parisi. 2022. Newborn screening research sponsored by the NIH: From diagnostic paradigms to precision therapeutics. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics 190(2):138-152.

Minten, T., N. B. Gold, S. Bick, S. Adelson, N. Gehlenborg, L. M. Amendola, F. Boemer, A. J. Coffey, N. Encina, A. Ferlini, J. Kirschner, B. E. Russell, L. Servais, K. L. Sund, R. J. Taft, P. Tsipouras, H. Zouk, ICoNS Gene List Contributors; D. Bick, R. C. Green, and the International Consortium on Newborn Sequencing (ICoNS). 2024. Data-driven prioritization of genetic disorders for global genomic newborn screening programs. medRxiv [Preprint]. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.24.24304797.

Ram, N. 2022. America’s hidden national DNA database. Texas Law Review 100(7):1253-1325.

Susanna Haas Lyons Engagement Consulting. 2024. What we heard: Newborn sceening in the United States. Presented to the Committee on Newborn Screening: Current Landscape and Future Directions at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. https://www.nationalacademies.org/documents/embed/link/LF2255DA3DD1C41C0A42D3BEF0989ACAECE3053A6A9B/file/D35FB72C883DD3F3496A747004FB20B434E54764D1D0?noSaveAs=1 (accessed December 18, 2024).

Taylor-Phillips, S., J. Geppert, C. Stinton, K. Freeman, S. Johnson, H. Fraser, P. Sutcliffe, and A. Clarke. 2017. Comparison of a full systematic review versus rapid review approaches to assess a newborn screening test for tyrosinemia type 1. Research Synthesis Methods 8(4):475-484.

Therrell, B. L., Jr., W. H. Hannon, D. B. Bailey, Jr., E. B. Goldman, J. Monaco, B. Norgaard-Pedersen, S. F. Terry, A. Johnson, and R. R. Howell. 2011. Committee report: Considerations and recommendations for national guidance regarding the retention and use of residual dried blood spot specimens after newborn screening. Genetics in Medicine 13(7):621-624.