Innovations in Pharmacy Training and Sustainable Practice to Advance Patient Care: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 2 Pharmacy Deserts and Workforce

2

Pharmacy Deserts and Workforce

KEY POINTS*

- Participants should identify keystone pharmacies in their area and support them to stay open. (Akiyode)

- Partnerships between academic institutions and health systems will be critical to increase access to pharmacy services, especially for medically underserved areas. (Youmans)

- Community pharmacies will not be viable or sustainable in the future without modernization (i.e., reimbursement and payment reform) of pharmacy practice. (Walmsley)

__________________

*These points were made by the individual workshop speakers/participants identified above. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

The first session focused on building an expanded workforce that serves pharmacy desert areas. Specifically, the objective of the session was to explore strategies to address pharmacy deserts and improve health outcomes and consider effective approaches and processes for recruiting and training pharmacy students. Moderator Ranti Akiyode, Howard University College of Pharmacy, said that addressing pharmacy deserts is critical for improving health outcomes in rural, suburban, and urban communities. The recent increase in pharmacy closures, coupled with a decrease in applications to schools, threatens access to pharmacy care for all communities,

she said. Innovative and collaborative approaches will be necessary to ensure a strong and sustainable workforce and eliminate pharmacy deserts.

CURRENT STATE: COMMUNITY PHARMACIES

Delesha Carpenter, UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, gave an overview of the state of community pharmacies and the impact of pharmacy closures. In 2020, nearly 90 percent of Americans lived within 5 miles of a pharmacy. However, recent years have seen many chain and independent pharmacies closing, with more closing than opening between 2018 and 2021, most often in Black and Latinx neighborhoods and low-income urban localities. Such areas already have limited access to health resources, said Carpenter, so closures are particularly impactful. A pharmacy desert can be defined by various metrics, including driving distance or time, but is generally an area with low access to pharmacies. Carpenter reported that over 50 million Americans (17.7 percent) live in pharmacy desert census tracts. In addition, almost 29 million (8.9 percent) live in “keystone pharmacy” census tracts (Mathis et al., 2025); keystone pharmacies would create a pharmacy desert if they were to close. Keeping these pharmacies open is a priority, said Carpenter, and several strategies are being considered to do so: higher or supplementary dispensing fees; getting them included in Medicaid and Medicare Part D preferred pharmacy networks; reforms to the system of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs); and addressing predatory health insurance practices.

Carpenter added that pharmacy closures have many impacts on a community, including decreased medication adherence, vaccinations, access to medications, ability to consult pharmacists, and employment opportunities. Individual patients face negative impacts as well, particularly those who rely on pharmacies to deliver medications or manage a complicated medication regimen, she said. Carpenter then emphasized the importance of considering a community’s characteristics when looking at the impact of a pharmacy closure. If a pharmacy closes but another pharmacy is in the vicinity, it may or may not have the capacity to absorb more patients or offer the same services. For example, not all pharmacies offer naloxone dispensing, transitions of care programs, or COVID-19 and flu testing. When keystone pharmacies close, communities lose access to these critical services. Another impact of closures is a loss of training opportunities for students, said Carpenter. They will lack experiential rotations and exposure to pharmacies serving high-need communities; these losses ultimately impact the pipeline of pharmacists who may eventually work in these or similar communities.

CURRENT STATE: PHARMACY WORKFORCE

According to the Census Bureau, pharmacists make up roughly 0.26 percent of the workforce, said Sharon Youmans, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) (El-Zein, 2024). In 2023, this translated to about 337,400 pharmacists. The Bureau of Labor Statistics projected a 5 percent growth in employment over the next 10 years, along with a 9 percent growth in the areas of medical diagnostics and medication management (MM). Despite pharmacy closures, Youmans said many opportunities remain for pharmacists.

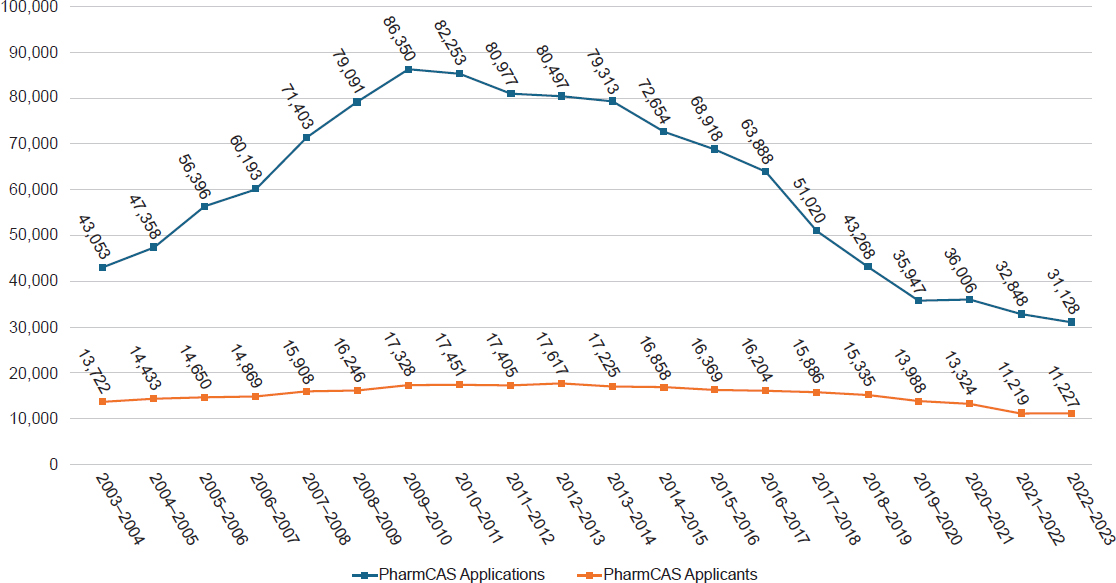

Pharmacy schools have increased considerably, from 80 in 2000 to 141 in 2025, according to American College of Clinical Pharmacy (AACP) data (Brown, 2020; Youmans, 2025). However, applications have remained fairly steady and dropped in recent years (Figure 2-1). A variety of factors influence a student’s decision to apply, said Youmans. On the positive side, students cite prestige of the doctorate, job security and salary, ability to improve health and well-being of others, wide range of potential careers, influence of family members, knowing a pharmacist and/or exposure to the profession, and opportunities to work with other health care professionals. Factors that dissuade some from applying include the high cost, curriculum difficulty, and board exam and licensure requirements.

Youmans commented on the number of schools and organizations that have developed strategies to increase enrollment in pharmacy school. These include recruiting students from nontraditional groups, such as veterans or engineers, and emphasizing the broad array of services pharmacists provide. Other strategies include reducing costs through scholarships or innovative educational approaches. For example, costs can be reduced by moving from a 4-year to a 3-year program, using technology to deliver curriculum online, or methodologies aimed at making education more efficient and economical. Youmans gave a specific example of the new the UCSF Pharm Tech to Pharm.D. Pathway Program, designed to increase pharmacists from medically underserved regions and prepare technicians to successfully apply to pharmacy school (UCSF, 2025). It is a 1-year program with monthly seminars on topics such as career opportunities, interviewing skills, and preparing a personal statement. Thus far, the program has accepted 23 students, more than double its initial target of 10 students, said Youmans.

BRIDGING CURRENT STATES AND EXPLORING SOLUTIONS

Walmsley agreed with other speakers’ comments that a growing number of community pharmacies are closing across the country in both rural and urban spaces for two main reasons. First, the practice model is challenging. It is virtually impossible to make community pharmacies sustainable without payment reform. Second, pharmacists are lacking in certain

SOURCE: Presented by Sharon Youmans on May 29, 2025. Created by and used with permission from American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy.

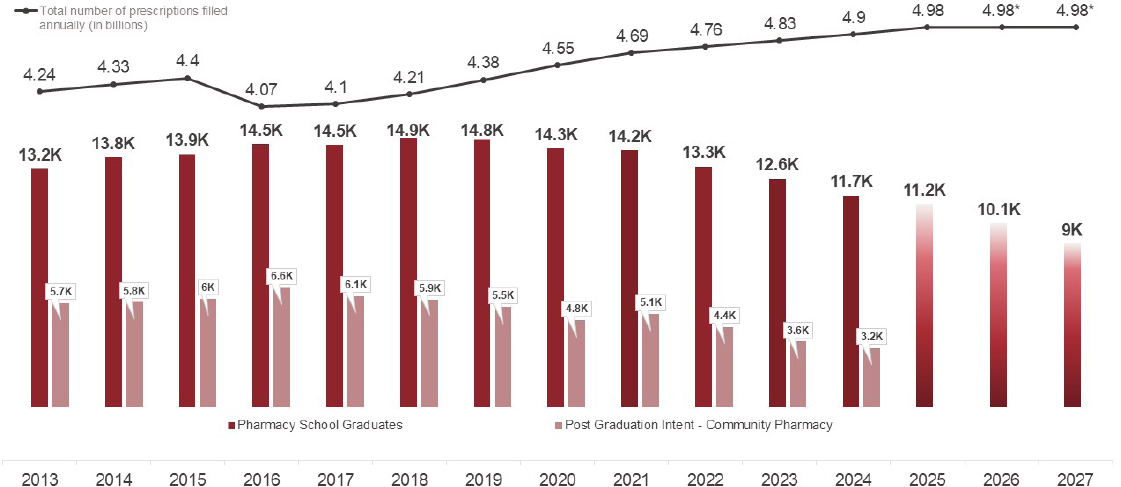

areas. Walmsley noted that Walgreens was forced to close some pharmacies in major metropolitan areas due to the difficulty of filling positions. The pharmacists graduating and entering the workforce each year are declining, while the demand for services is increasing (Figure 2-2). Furthermore, a smaller proportion of graduates are choosing to enter community pharmacy. The question, said Walmsley, is how to increase the students who want to go into community practice, while at the same time transforming care delivery in a way that is safe, effective, and accessible for patients?

To address these issues, Walgreens has focused on five main pillars:

- Pharmacy Modernization: Defining the future of pharmacy and focusing investments on the next generation of pharmacy—both people and infrastructure.

- Pharmacy Operating Model: Optimizing and enabling operational excellence through the advancement of technology, centralized services, and community pharmacy administration.

- Core Clinical Programs: Continuing to manage and scale key pharmacy programs, including immunizations.

- Core Rx Profitable Growth: Developing key programs that benefit patients and improving patient experience.

- Elevating the Role of the Pharmacist: Continuing to advocate for provider status, ensuring patient safety and pharmacy compliance, partnering with critical stakeholders.

Walmsley described some of the specific solutions that Walgreens has pursued. For example, the Walgreens Deans Advisory Council was formed in 2024 to work collaboratively on solutions for the challenges facing community pharmacies (Walgreens Boots Alliance, 2024). Walmsley noted how the success of Walgreens and other community pharmacies is tied together with the success of colleges of pharmacy, saying, “we all win and lose together.” The council has four main objectives, she said: evolving the community practice model, improving on aspects of pharmacy practice strategy and administration, collaborating on ways to enhance the talent pipeline, and elevating community pharmacy practice as a practice setting of choice.

Walgreens has also focused on improving the pathway from technician to Pharm.D. It employs over 50,000 technicians, said Walmsley, but only 1 percent of these go on to get a Pharm.D. Walgreens surveyed its technicians and found that 75 percent are interested in pursuing a Pharm.D., but they are dissuaded by the costs of tuition and fees; the challenges of balancing work, family, and school responsibilities; and the lack of prerequisite courses (Simmons et al., 2025). In response, Walgreens developed several solutions for its employees. PharmStart is a fully funded online education program designed to help its technicians meet the prerequisites for pharmacy school (Walgreens Boots Alliance, 2025). The Pharmacy Educational

NOTE: Data drawn from AACP, Fall 2022 Degrees Conferred—Profile of Pharmacy Students, fall-2022-pps-degrees-conferred_0.xlsx (live.com); AACP, Fall 2021 Degrees Conferred—Profile of Pharmacy Students, fall-2021-pps-enrollments-appendix.xlsx (live.com); AACP, Fall 2020 Degrees Conferred—Profile of Pharmacy Students, fall-2020-pps-degrees-conferred.xlsx (live.com); AACP, Fall 2019 Degrees Conferred—Profile of Pharmacy Students, fall-2019-pps-degrees-conferred.pdf (aacp.org); AACP, Fall 2022 Enrollments—Profile of Pharmacy Students, fall-2022-pps-enrollments-appendix_0.xlsx (live.com); AACP, Fall 2023 Enrollments—Profile of Pharmacy students, fall-2023-pps-enrollments-appendix.xlsx; AACP, Fall 2023 Degrees Conferred—Profile of Pharmacy Students, fall-2023-pps-degrees-conferred.xlsx; and AACP Graduating Student Survey, Graduating Student | AACP.

SOURCE: Presented by Lorri Walmsley on May 29, 2025. Created by and used with permission from Lorri Walmsley at Walgreens.

Assistance Program offers up to $40,000 in tuition assistance to ease the financial burden, while a 401(k) match program helps team members who are repaying student loans earn their full retirement match even if they can’t contribute their share (Walgreens, 2025). These programs, said Walmsley, are designed to help employees achieve their educational and career goals while minimizing the burdens.

Walmsley shared two other strategies used by Walgreens to improve patient care despite shortages of pharmacists: micro-fulfillment centers (MFCs) and centralized services (CS). Walgreens has 12 MFCs across the country that use technology and robots to fill routine medications. A traditional Walgreens pharmacy gets around 40 percent of its prescriptions filled in MFCs, which frees up staff to provide additional clinical services. This program, she said, has resulted in significant improvement in clinical services provided, such as vaccinations and medication synchronization. Another strategy is a CS system. It supports community pharmacies with tasks such as data entry, data review, and phone calls so that team members have time for patient-facing services.

DISCUSSION

Akiyode and Marie Chisholm-Burns, Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU), moderated a discussion among panelists and participants, covering several different issues.

Strengthening the Technician to Pharmacist Pipeline

Akiyode noted that both Walmsley and Youmans discussed the importance of educating and training technicians to alleviate the shortage of pharmacists. She asked them to elaborate on this pipeline and address any challenges they see. Youmans responded that the UCSF Pharm Tech to Pharm.D. Pathway Program has been well received by the health systems in the area and the state pharmacist associations. UCSF does not have the capacity to accept everyone who is potentially interested in this type of program, she said, but it could be easily replicated at other institutions. The program allows people to explore the possibility of becoming a pharmacist and gives them resources and information about how to pay for education and balance the demands of work, family, and school. Addressing these barriers for technicians would better equip them to successfully train as pharmacists. Another facilitator of pharmacy workforce development would be offering different ways to deliver the curriculum and allow more flexibility that could promote nontraditional paths into higher levels of pharmacy training. Furthermore, she said, there is a gap in faculty

development in how to create a supportive environment for different types of students.

Youmans noted that strengthening pathways into pharmacy could make a real difference in the workforce. For example, in California, 51 percent of technicians but only 5 percent of pharmacists identify as Hispanic (California Health Care Foundation, 2021). This is a “huge, huge gap” with “huge, huge potential.” Walmsley added that the technician population also could ameliorate the issue of pharmacy deserts. Many technicians already work in these areas and want to stay. She further commented that pharmacy education programs may need to be modified so technicians can stay in their communities while studying (e.g., through online programs or asynchronous classes). Technicians are likely to be adults with homes, children, and financial obligations. If students have to leave their communities to attend school, she said, they may not return. As an employer, Walgreens is exploring what kind of support these employees need to further their career in pharmacy.

Both Youmans and Walmsley said they expect to have more data about the successes and challenges of their pipeline programs in the upcoming years.

Increasing Interest in Community Pharmacy

Recalling Walmsley’s statement that only about 30 percent of graduating students are interested in community pharmacy, Akiyode asked panelists for strategies that could make it more attractive. Walmsley identified two important factors: access to community pharmacists and faculty role models. During students’ required rotations, there is a need to “make pharmacy cool again” by showing students all the varied activities that community pharmacists do. Counting pills is not “cool” to the average student, she said, so offering opportunities for them to try other roles could be key to changing attitudes. Walmsley has observed that fewer practicing community pharmacists seem to be on faculty at colleges of pharmacy. Students aspire to be like the faculty they see, she said, which means seeing role models and real-world examples of community pharmacists. Youmans added that she has seen a disconnect between ideas students have in their heads and what is happening in the world. Students often have a misconception that community pharmacy is not as challenging or interesting as clinical pharmacy; inspiring learners to question these ideas, she said, can instill a curiosity about all potential career paths. A participant suggested that the attractiveness of community pharmacy is also impacted by the financial viability of the business model. He asked how pharmacies could be made more sustainable so that they can continue to operate in the communities that rely on them. Walmsley replied that payment reform “has

to happen today.” Pharmacies are filling prescriptions at a loss, and this is not a sustainable model. Furthermore, making time and space for other clinical activities that pharmacists get paid for would go a long way toward ensuring sustainability. Several avenues exist for making pharmacy more efficient, she said, including using technology and technicians. Redesigning how community pharmacies practice and deliver care in a way that is effective, efficient, and sustainable, she noted, may be the key to sustainability.

Targeted Recruitment and Funding

A participant expressed concerns about the shortage of pharmacists in rural and underserved areas by asking panelists for their perspectives on programs that focus on recruitment and funding in such pharmacy deserts. Chisholm-Burns responded that Oregon has programs that will repay student loans for health professionals who commit to serving in medically underserved areas. Walmsley added a note of caution that many state loan repayment programs do not include pharmacists and said that advocating for expanding such opportunities is important to pursue. Walmsley shared another approach for improving the rural workforce, which is to recruit students from high school; one medical school program in Oklahoma targets students involved in 4H and Future Farmers of America, who are often very leadership oriented. Walmsley suggested that pharmacy schools could learn from examples like this and also partner with employers to get creative about how to fill the workforce gaps in underserved areas. Youmans described a program at UCSF in which students came to San Francisco for the first years of pharmacy school and then returned home to the Central Valley to complete their rotations and residencies. She noted that many organizations are interested in supporting these types of programs as a way to increase the workforce in underserved areas. Chisholm-Burns underscored how recruiting students directly from these areas can lift financial and other burdens they have with finding housing in rural areas for rotations or residencies in these communities.

This page intentionally left blank.