Innovations in Pharmacy Training and Sustainable Practice to Advance Patient Care: Proceedings of a Workshop (2025)

Chapter: 3 Well-Being of the Pharmacy Workforce

3

Well-Being of the Pharmacy Workforce

KEY POINTS*

- Despite strategies to modify individual factors that play a role in burnout and well-being, the most effective interventions are at the systems and organizational levels. (Harris)

- It can be helpful to realize that challenges exist across multiple disciplines, and the solutions may lie in working together. (Brandt, Harris, Johnston)

- Burnout is an issue among not just practicing pharmacists but also students. (Lockman)

- Lack of recognition can contribute to frustration and burnout. (Speedie)

__________________

*These points were made by the individual workshop speakers/participants identified above. They are not intended to reflect a consensus among workshop participants.

Session 2 explored workplace environments that foster well-being of the pharmacy workforce. The objective was to discuss innovative strategies for creating safe, supportive, and interprofessional work environments that reduce clinician burnout and empower pharmacists within their chosen area (e.g., community, health system, academia, policy, managed care, industry, research). Suzanne Harris, University of North Carolina Eshelman School of Pharmacy, set the stage for the roundtable discussion with a brief presentation on the well-being of the workforce, the problem of burnout, and efforts that have been made to address these issues.

Burnout is a significant issue in all health professions, including pharmacy, said Harris. A 2023 systematic review across eight countries found that 51 percent of pharmacists were experiencing burnout (Dee et al., 2023). The consequences include work absences, leaving the profession, personal deterioration, impacts on personal and professional relationships, poor work performance and errors, and poor patient interactions. Numerous national organizations have undertaken efforts to address burnout; including the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience, which released the National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being in 2022. Making investments to reduce burnout and improve well-being benefits individual pharmacists, the systems they work in, and the patients they serve, said Harris. On the organizational and societal levels, improved well-being can improve productivity, absenteeism, turnover, and errors. On the individual level, it contributes to improved morale and purpose, job satisfaction, work–life integration, and physical and mental health.

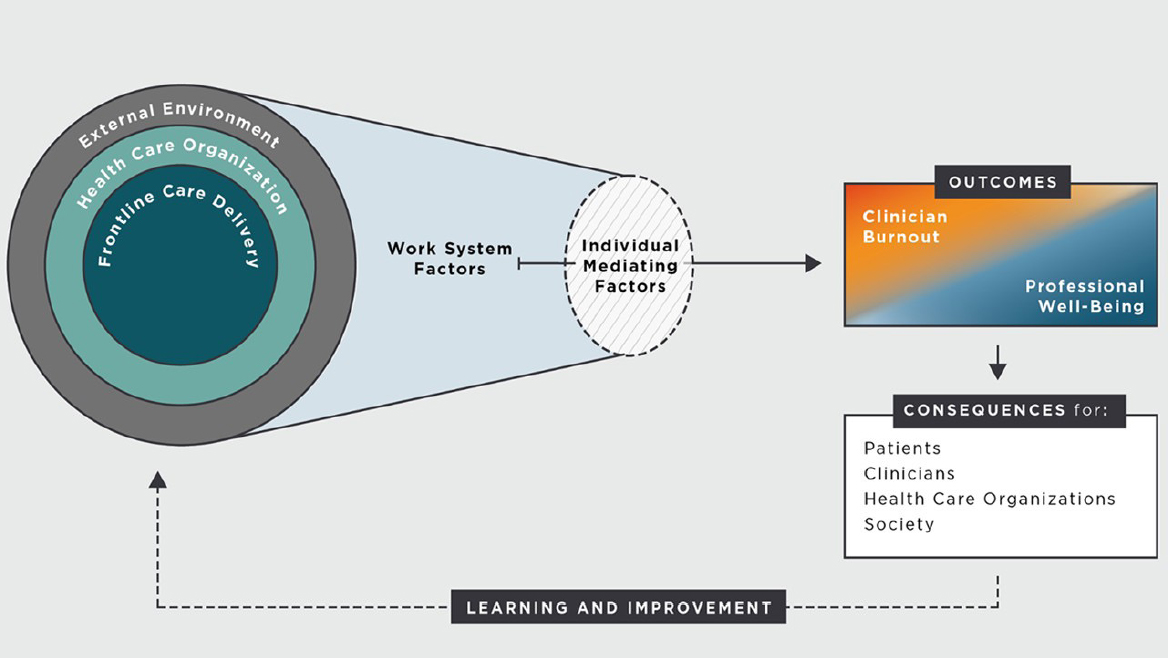

Many factors on different levels contribute to clinician well-being, said Harris. It is influenced by individual factors, work system factors, and the external environment (see Figure 3-1). A fair number of external factors are outside the control of the individual or even one particular institution, she noted, and while individual factors such as resilience can mediate work system or environmental factors, they cannot entirely alleviate them.

Harris shared a list of factors that negatively contribute to well-being, which could be across the profession of pharmacy, within specific workplaces, or linked to key roles:

- Across the profession: workforce shortages and imbalances, financial pressures from rising costs and low reimbursement, evolving technologies, a lack of flexibility and work–life balance;

- Hospital setting: inadequate administrative and teaching time, too many nonclinical duties, feeling contributions are underappreciated, high-stress environment with little room for error;

- Community setting: time constraints and performance metrics, multiple responsibilities, financial pressures, time spent managing drug shortages;

- Faculty role: overwhelming workload, inadequate resources, workplace inefficiencies, unexpected factors;

- Resident role: long working hours, time and deadline pressure, medical emergencies, financial pressures; and

- Student role: too little time, overwhelming academic workload, competitive culture, non-coursework commitments.

SOURCE: Presented by Suzanne Harris on May 29, 2025. NASEM, 2019.

If burnout is primarily driven at the organizational and systems levels, said Harris, the solutions would also be expected to stem from those levels. She pointed to priority areas for well-being recommended by the National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being that can be applied to pharmacy (see Table 3-1). The main message, she said, is that quality patient care requires a thriving workforce, which means a culture and environment that fosters well-being. Harris offered another way of thinking about burnout, saying that it is the flipside of professional fulfillment; if burnout is “a feeling of exhaustion, distress, and cynicism related to one’s job,” professional fulfillment is “a sense of engagement, reward, and contentment with one’s career.”1 Efforts to improve it—such as giving workers more control over their schedules, or ensuring alignment between personal and organizational values—can also reduce burnout, she added.

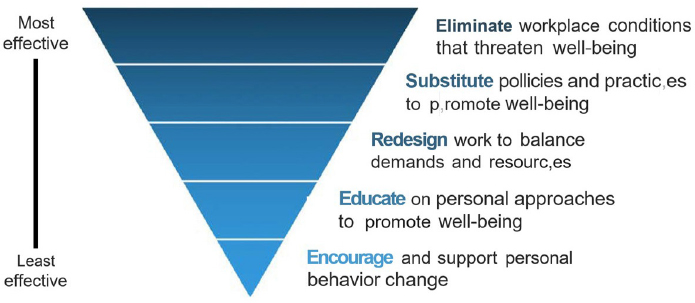

Despite strategies to modify individual factors that play a role in burnout and well-being, said Harris, the most effective interventions are at the systems and organizational levels (see Figure 3-2). The higher-level

TABLE 3-1 Considering Priority Areas for Pharmacy Workforce Well-Being

| Strategy | Examples |

|---|---|

| Positive work and learning environments and culture |

|

| Compliance, regulatory, and policy barriers |

|

| Diverse and inclusive health workforce |

|

| Measurement, assessment, strategies, and research |

|

| Effective technology tools |

|

| Mental health and stigma |

|

| Well-being as a long-term value |

|

SOURCE: Presented by Suzanne Harris on May 29, 2025. Adapted from NASEM, 2019. National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26744/national-plan-for-health-workforce-well-being.

___________________

1 Well-Being Index, 2025. https://www.mywellbeingindex.org/downloads/wbi-a-path-forward/ (accessed October 22, 2025).

SOURCE: Presented by Suzanne Harris on May 29, 2025. Adapted from National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health by AACP (2022) and used with permission from American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy.

interventions are more likely to have a sustained impact over time compared to the lower-level, individual interventions.

Just before opening the discussion to panelists, Harris projected a select list of resources that included action plans and resource guides:

NAM:

- National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being (https://nam.edu/publications/national-plan-for-health-workforce-well-being/)

ASHP:

- Implementing Solutions: Building a sustainable, healthy pharmacy workforce and workplace (https://wellbeing.ashp.org/-/media/wellbeing/docs/Implementing-Solutions-Report-2023.pdf)

- Resource Guide for Well-Being and Resilience in Residency Training (https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/professional-development/residencies/docs/ASHP-Well-Being-Resilience-Residency-Resource-Guide-2023.pdf)

AACP:

- Creating a Culture of Well-Being: A Resource Guide for Colleges and Schools of Pharmacy (https://www.aacp.org/sites/default/files/2022-08/creating-a-culture-well-being-guide.pdf)

National Collaborative for Improving the Clinical Learning Environment:

- Compendium of Well-Being Resources 2024 (https://storage.googleapis.com/wzukusers/user-27661272/documents/ff6470da0e104ee5bc9422705bb52ef0/NCICLE Compendium of Well-Being Resources.pdf)

PANEL DISCUSSION

Harris moderated a discussion on the topic of well-being and burnout; she asked the four panelists to comment on a variety of questions and topics.

Priority Areas

Harris asked each panelist to consider the seven priority areas identified by the National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being (see Table 3-1) and speak about strategies within these areas that they have seen in their own work. Nicole Brandt, University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, MedStar Health, replied that the University of Maryland in Baltimore is fortunate to have an interprofessional campus, with schools of medicine, pharmacy, nursing, social work, physical therapy, and dentistry. It is intentional about offering interprofessional opportunities to students, she said, with the belief that training together helps people work better together. Interprofessional training and practice can provide support. When pharmacists get frustrated and feel like they don’t have control of their work environment, Harris interjected, it can be helpful to realize that challenges like burnout exist across multiple disciplines affecting the broader workforce and not just pharmacy. S. Claiborne “Clay” Johnston, Harbor Health, agreed with the potential for interprofessional collaboration to improve well-being. As a medical doctor, Johnston sees burnout as pervasive in health care right now; it is not specific to one particular profession but fundamental to the current system. Working across disciplines allows health professionals to recognize the diversity in expertise and perspectives and tap into different solutions and ideas, he added. Kashelle Lockman, Society of Pain and Palliative Care Pharmacists, University of Iowa, said that interprofessional education has been foundational to her practice as a palliative care pharmacist. That team can be “incredibly useful” for mitigating the factors that can contribute to burnout. For example, palliative care team members, such as social workers and chaplains, can help support the team when navigating the emotional process of a patient’s death. Lockman noted, however, that the hierarchies and power dynamics on some interprofessional teams can actually contribute to burnout by making people feel undervalued and underappreciated. One way to make this less likely, she said, is to have

clear role allocations and open discussions with team members about how to work together better.

Financial Models and Well-Being

Harris observed that several speakers discussed the challenges with current financial models for pharmacy and the impact on sustainability. She asked panelists about the relationship between financial instability and pharmacist well-being. Johnston shared a story to illustrate the impact of financial constraints on providing quality care. As the inaugural dean of the University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School, he (and his colleagues) tried to tear down and rebuild the medical school model in a way that made more sense. They brought multidisciplinary groups together to provide care by condition, which improved outcomes. However, he said, insurance companies would not modify their payment systems for this work. These financial constraints are nearly impossible to overcome, he said, even when building a medical school from the ground up. Johnston’s new company, Harbor Health, brings insurance and the care group together. Within this integrated system, it is easier to see the roles of different health professionals and evaluate the costs associated with care. With skyrocketing drug costs, said Johnston, pharmacists need to drive the leadership in thinking about appropriate use of medications. Harbor Health aims to put pharmacists in these positions so that they can use their expertise and perspective to improve the health system as a whole. This is “cool” work that generates substantial value, he said; it attracts people to the profession and improves professional satisfaction and well-being.

Burnout in Students

Lockman commented on burnout as an issue among not just practicing pharmacists but also students. The financial burden of school is a significant stressor, she noted. Adding a residency delays the repayment of student loans and further contributes to financial distress, and finding creative ways to make school more affordable may be one way to help mitigate such stress. For example, the University of Utah has a program supported by philanthropy, First Year Free (University of Utah, n.d.). The tuition of all accepted students is covered for 1 year, and while food and housing are not included, students are satisfied with the program, and applications have risen. Students and residents have lives just like everyone else, said Lockman, and schools need to help them navigate their challenges and model resilience and well-being. For instance, if a student has a significant personal crisis, they need to know that it is okay to ask for time or support, rather than feeling like they have to “prove themselves.” Lockman said that

the importance of well-being and self-care can be reflected in every aspect of education, from selection criteria to residency requirements. She encouraged educators to be curious about each piece of the training process and assess the value and potential harm of decisions related to program design and implementation.

PRIORITIZING STRATEGIES FOR WELL-BEING

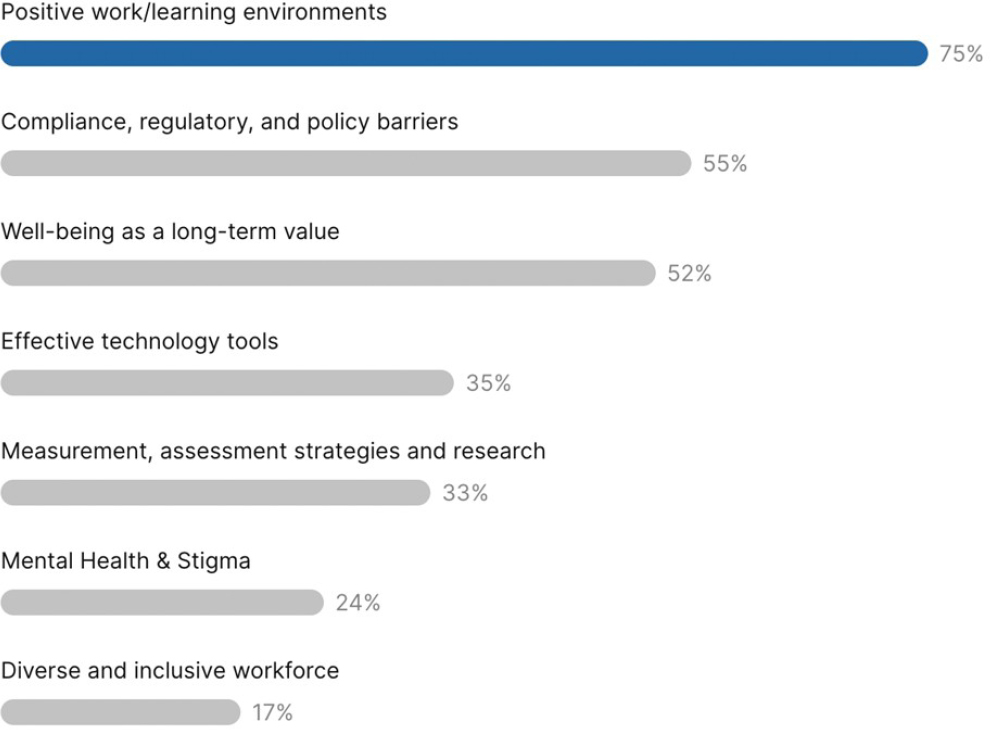

Participants were asked to work in small groups to look over a list of strategies (see Table 3-1), then discuss which could be prioritized to mitigate burnout and foster the well-being of the pharmacy workforce. Each group shared their thoughts via an online poll; virtual participants uploaded their ideas individually. After reviewing the inputs (see Figure 3-3), Harris asked participants to share why a particular strategy was prioritized over others on the list.

SOURCE: Presented by Suzanne Harris on May 29, 2025. Results of online Slido poll conducted among in-person and virtual workshop participants, May 29, 2025.

Positive Work/Learning Environments

Phillip Rodgers, professor and chair of family medicine at the University of Michigan, shared his perspective on the work environment. Redesigning the processes and environments of workplaces can be one way of addressing well-being and burnout, he said. Rodgers emphasized the importance of focusing on relationships rather than transactions in patient care encounters, team member interactions, and leadership work. Johnston agreed with the importance of relationships and said that people choose the health professions because they want to help people; he suggested that technology could be leveraged to take over some of the transactional elements so that pharmacists could focus on relationships. A participant emphasized that positive relationships among the health care team can mitigate or reduce burnout.

Another important aspect of a positive work environment, said Speedie, is being seen and recognized for one’s expertise and skills. She observed that patients may not even know who the community pharmacist is, and this can contribute to frustration and burnout. Furthermore, other health professions team members sometimes do not acknowledge the pharmacists as an important contributor to patient care. Speedie said that pharmacists need “to speak up” but that a solution is needed at the interprofessional level as well. She added that in addition to recognition, a positive work environment is one in which employees are treated like people with lives outside of work, and the employer is flexible and supportive of people’s needs.

Effective Technology Tools

The industry is ripe for greater integration of technology, said Hogue. There have been some investments in leveraging technology, such as Walgreen’s use of micro-fulfillment centers (MFCs) and robotic prescription filling, but at the local community pharmacy, “the telephone’s ringing off the hook, the drive-through is beeping, the people are crying.” Part of the reason for the lack of innovation, said Hogue, is a fear that technology will take away pharmacist jobs. He argued that if technology or technicians were to take over putting pills in a bottle, this would free up pharmacists to focus on taking care of patients and making medicines work. Adopting technology to alleviate workload and improve the experience in the pharmacy would reduce work stress and improve well-being, said Hogue.

Measurement, Assessment Strategies, and Research

A participant noted that while creating a positive work environment is a valid goal, there is a gap in research and assessment to determine what

components make up such an environment and have a positive impact on well-being. The environment is an outcome, not a strategy, she said, adding that research on the root causes of burnout and challenges to wellbeing is key to evidence-based practices for attaining that positive work environment. Another participant agreed and noted the many solutions and strategies, on both institutional and individual levels, but it is critical to assess these strategies to know what works. Harris observed that both quantitative and qualitative assessments are necessary to achieve a full understanding of the factors that lead to burnout and the factors that can mitigate burnout.