Bridge Construction Inspection Training Resources and Practices (2025)

Chapter: 2 Literature Review

CHAPTER 2

Literature Review

Introduction

This chapter documents findings obtained from the literature review. The purpose of this chapter is to establish the foundation and framework for the results presented in Chapters 3 and 4, which include the survey results and case examples. It is worth noting that there is a diverse range of literature pertaining to bridge construction inspection. This chapter focuses on the main topics related to training resources and practices of bridge construction inspection. The chapter starts with a brief discussion of bridge construction inspection practices, including the responsibilities of bridge construction inspectors. Next, the chapter discusses typical components of bridge construction inspection. The chapter then presents the core competencies of bridge construction inspectors. Finally, the chapter discusses bridge construction inspection training resources and the career development of bridge construction inspectors.

Overview of General and Bridge Construction Inspection

Bridge construction inspection plays an essential role in the state and federal highway systems. To ensure the safety and quality standards of a bridge during construction and operation, state DOTs depend on construction inspectors to ensure that the construction work is carried out in accordance with the provided plans and specifications and that it complies with the contract documents. For bridge construction, inspectors are tasked with performing inspection of both permanent structures (e.g., foundations, substructures, and superstructures) and temporary works (e.g., formwork, falsework, shoring systems, and others). Fustok and Alemi (2000) emphasized the critical role of the inspector in verifying the compliance of permanent structures with project plans and specifications, as well as ensuring that construction works and products meet quality standards. Additionally, the inspector is tasked with examining temporary works proposed for use by the contractor.

The construction inspection process involves several main steps: (1) preparation, (2) conducting an on-site review (e.g., a physical review), (3) evaluating data, and (4) reporting. Under the preparation step, the construction inspector reviews inspection objectives, plans, and guidelines and gathers preliminary data. The FHWA emphasizes the importance of the construction inspector reviewing the following items prior to conducting an on-site review:

- Plans and specifications

- Correspondence, change orders, and material testing quality levels

- Previous reviews and progress reports

- Pre-award issues and bid tabulations

- Construction inspection program and emphasis areas

- State policy and procedure manuals

- Organization, staffing, and authority

- Applicable federal and state regulations (FHWA 2004).

Under the on-site review step, many inspection items can be examined during the construction process. Figure 1 shows a sample checklist of construction inspection items adapted from the FHWA (2004). Qualified construction inspectors are equipped with the expertise to skillfully gather review information through meticulous observation, in-depth discussions, and comprehensive file reviews, eschewing reliance solely on a checklist. The level of scrutiny applied to each item during the inspection is contingent upon the breadth of the inspection and the available time (FHWA 2004).

Notes: NPDES = National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System; SHPO = State Historic Preservation Office; COE = U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; FWS = U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Under the evaluating data step, construction inspectors analyze data collected from their field observations that are typically recorded following the inspection. The FHWA provides six steps for evaluating construction inspections:

- Document facts by recording information obtained from observations, test results, actions taken, and other relevant details

- Conduct observations by potentially requesting additional inspections, measurements, or tests to validate opinions or address concerns

- Seek input from appropriate technical and authoritative sources to ensure well-informed decisions

- Provide guidance when necessary without directly controlling the operation as a construction inspector

- Reach conclusions regarding the acceptability of operations, actions taken, the final product, and the quality of supervision

- Make decisions based on the inspection process and promptly inform all affected parties (FHWA 2004).

During the reporting step, construction inspectors must meticulously record their observations, facts, and opinions. It is their duty to maintain a comprehensive and precise log of the work carried out by contractors. Keeping a detailed written diary of inspection activities, including the work inspected, any noteworthy occurrences, and significant discussions, is crucial. The FHWA states that “inspection reports should have substance rather than just verbose wording. . . . Reports should be as specific as possible, and ambiguity should be avoided. Hearsay should never be documented unless upon further review facts are found to support the hearsay” (FHWA 2004).

The FHWA/National Highway Institute (NHI) publication Bridge Construction Inspection Instructor-Led Training states that the main responsibilities of the construction inspector vary among state DOTs, but these responsibilities typically include:

- Understanding the contract documents thoroughly.

- Monitoring the contractor’s conformance with contract documents:

- Notifying the contractor of any known deviation from the contract documents.

- Documenting and reporting whenever materials or work performed fail to fulfill the contract requirements.

- Informing the engineer of progress, problems, and instructions given to the contractor.

- Exercising good judgment (FHWA/NHI 2022).

Materials Field Inspection of Bridge Construction

For bridge construction projects, Fustok and Alemi (2000) emphasized three main types of material inspections: concrete, reinforcement, and structural steel. For concrete, the main considerations for the material inspection include that:

- The contractor is responsible for all concrete mix designs;

- The mix designs are based on the specification requirements;

- The inspector reviews and approves the proposed concrete mix designs;

- The inspector reviews methods and frequency of sampling and testing of concrete; and

- Concrete cylinders are sampled, cured, and tested to determine their compressive strength.

The typical tests to check concrete properties include tests for:

- Cement content;

- Cleanness value of the coarse aggregate;

- Sand equivalent of the fine aggregate;

- Fine, coarse, and combined aggregate grading; and

- Uniformity of concrete.

For reinforcement, considerations for the material inspection include that:

- The inspector checks reinforcing steel properties and fabrication based on the specifications.

- The inspector reviews a certificate of compliance and a copy of the mill test report for each heat and size of reinforcing steel.

- Reinforcement steel should be loaded, transported, unloaded, and handled in a way that prevents damage.

- If prolonged exposure is expected, reinforcement steel should be protected from the weather.

- Unloaded reinforcement steel should be blocked off the ground and stored in piles separated by size and type.

- For epoxy-coated reinforcing bars, the inspector checks the coating thickness and adhesion requirements based on the specifications. Epoxy coatings need to be touched up, even after placement [Fustok and Alemi 2000; Georgia DOT (GDOT) 2021].

For structural steel, the considerations for the material inspection include that:

- The inspector reviews a copy of all mill orders, certified mill test reports, and a certificate of compliance for all fabricated structural steel.

- Steel piling, sway bracing, and concrete piling surfaces should be prepared for special protective coatings.

- The inspector pays special attention to structural steel used to fabricate fracture-critical members (Fustok and Alemi 2000; GDOT 2021).

- The coating integrity on steel elements must be maintained during erection. The inspector verifies the coatings inspection at the fabricator, inspects for coating damage, and verifies that erection does not damage coatings. If any damage is identified, it must be repaired in accordance with approved repair procedures using approved materials (FHWA/NHI 2022).

Inspection of Bridge Construction Activities and Components

Bridge construction inspectors spend most of their time in the field, ensuring that bridges are built according to project plans and specifications. There are multiple operation inspections of a bridge during construction. Fustok and Alemi (2000) highlighted five operation inspections: (1) layout and grades, (2) concrete placing, (3) reinforcement placing, (4) welding of structural steel, and (5) high-strength bolts.

For the layout and grade inspection, the inspector uses the reference points to check the bridge geometry, including horizontal and vertical alignment. The typical inspection activities related to bridge construction layout and grades include:

- Pile locations and cutoff elevations,

- Footings location and grades,

- Column pour grades,

- Abutments and wing-wall pour grades,

- Falsework grade points,

- Control grade points, and

- Overhang jacks and the edge of the deck (Fustok and Alemi 2000).

For concrete placing inspection, the inspector checks each load of ready-mixed concrete with a ticket that shows the volume of concrete, mix number, time of batch, and reading of the revolution counter. The typical inspection activities related to concrete placing include:

- Ensuring that the concrete meets the specification requirements, such as elapsed time of batch, number of drum revolutions, concrete temperature, and concrete slump;

- Ensuring that acceptable formwork materials are used, such as lumber, plywood, metal, or plastics;

- Checking tools and vibration to consolidate the concrete and ensuring that no segregation occurs during the concrete placement;

- Checking the thickness and height of the soffit in the stems while placing the concrete;

- Ensuring that there is no disturbing of the forms or projecting reinforcing bars after placement;

- Ensuring that there is no displacement in reinforcement bars; and

- Ensuring that the appropriate application of curing methods and materials has occurred (Fustok and Alemi 2000; GDOT 2021).

For inspection of reinforcement placing, the inspector checks the grade, size, quantity, and location of steel rebar. The typical inspection activities related to reinforcement placing include ensuring that:

- The reinforcement is firmly and securely held in position by wiring,

- The rebar mat at each intersection is tied on the outer edges and at alternate intersections within the mat,

- The rebar mat is supported using chairs fastened with cast-in wires,

- Dowel bar positions meet the specification requirements, and

- Reinforcing steel is protected from bond breaker substances (Fustok and Alemi 2000; GDOT 2021).

The inspector is responsible for the quality assurance inspection of all welding of structural steel. The inspector verifies that equipment, procedures, and techniques are in accordance with specifications. For the inspection of high-strength bolts, the inspector is responsible for checking the marking and surface condition of bolts, nuts, and washers to ensure compliance with specifications. Additionally, the inspector is responsible for monitoring the installation of the work to ensure that the selected procedure is routinely and properly applied (Fustok and Alemi 2000).

Bridge Foundations

A bridge’s foundation is critical to the bridge’s safety and performance. Structural excavation for a bridge is typically the same as for any other concrete structure. The bottom of the excavation must be cut to the correct elevation and provide a firm and uniform foundation. The excavation must be large enough to provide sufficient space around the structure for forming and other operations. Temporary shoring is often used due to the limited construction work space for bridge replacement projects.

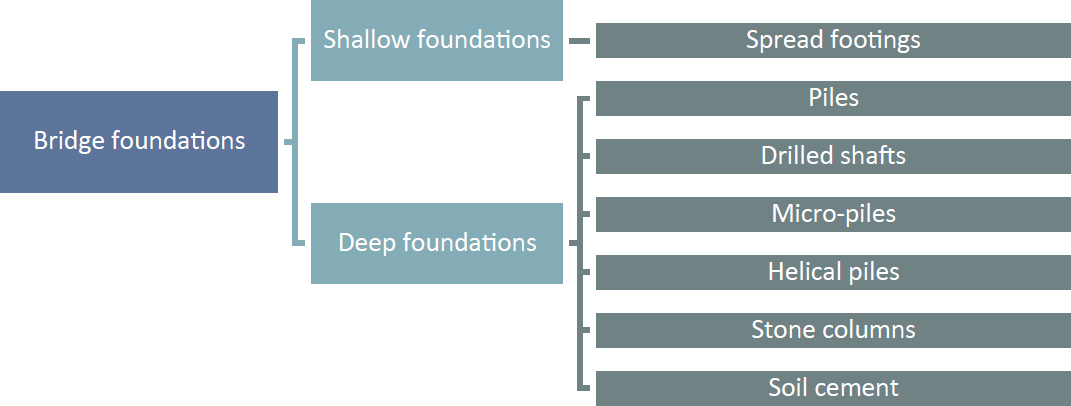

There are two types of foundation systems—shallow and deep. Shallow foundations bear on surface soils or rock at the bottom of an excavation. Shallow foundations are typically referred to as spread footings. Deep foundations penetrate the soil layers near the surface and are supported by strata below the surface layer. Deep foundations typically include piles, drilled shafts, micro-piles, helical piles, stone columns, and soil cement columns. Figure 2, adapted from FHWA/NHI (2022), shows typical types of foundations for bridges.

It is essential for construction inspectors to have knowledge and experience in foundation construction, including foundation layout, foundation verification, and foundation inspection items based on substructure type (footing, piles, drilled shafts, micro-piles, helical piles, stone columns, soil cement, soil anchors, and soil nails, cofferdams, and others). Verification measurements are used by the inspector to ensure that the foundation is accurately positioned in accordance with the project plans. The accuracy of the verification depends on the tools and methods being used.

Table 1 summarizes typical inspector responsibilities for the main types of bridge foundation construction inspections.

Bridge Substructures

Figure 3, adapted from FHWA/NHI (2022), shows typical types of substructures for a bridge. The two main bridge substructures are abutments and piers. Abutments act as the end supports for the bridge girders and deck. There are several types of abutments, including conventional, cantilevered, isolated pedestal stub, mechanically stabilized earth (MSE), gravity, integral, and semi-integral. Piers are intermediate supports for the bridge superstructure between abutments. There are several types of piers, including solid, hammerhead, multi-column, and pile-bent.

The inspection of substructure construction is crucial to a bridge. Inspectors are responsible for ensuring that each substructure element is built to the correct size and is in the correct location with the correct construction materials. FHWA/NHI noted that “if any of these items are not in compliance with the plans and specifications, the substructure may not be able to support the bridge as intended for the duration of its design life” (FHWA/NHI 2022). Table 2 summarizes typical inspector responsibilities for three main substructure types (abutment, concrete pier, and MSE wall).

Bridge Decks and Superstructures

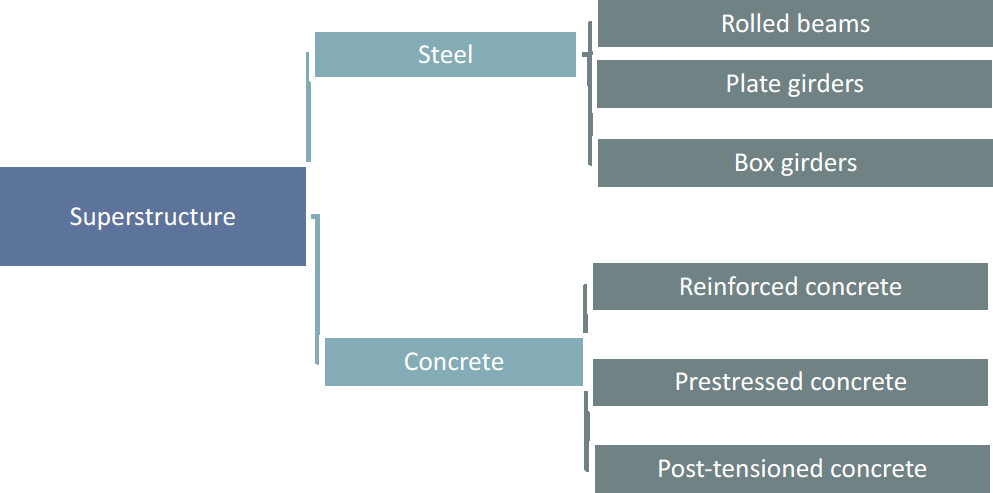

Construction inspectors are responsible for inspecting many items in bridge superstructures during construction. Figure 4, adapted from FHWA/NHI (2022), shows the basics of bridge substructures based on materials. For steel bridges, modern bridge steel members include rolled beams and plate and box girders. Rolled beams are commonly used in shorter-span steel bridges. Rolled beams are produced at the steel mill and cut to length. Plate girders are common bridge members used to span long lengths. Plate girders are fabricated from individual plates cut to length and welded to form the web and flanges. Box girder bridges are plate girders with two web plates. Steel box girders are constructed similarly to plate girders (FHWA/NHI 2022). The construction of steel bridges typically uses high-strength bolts and welding. Modern bridge concrete members include reinforced concrete, prestressed concrete, and post-tensioned concrete.

Structural steel and precast concrete members (e.g., girders) are typically inspected at the fabrication site. In the field, construction inspectors inspect these members for conformance with the plans and specifications as well as for any damage that may have occurred during transportation to the project site. It should be noted that construction inspectors are responsible for checking contract drawings, specifications, and submittals to ensure the timely detection of problems during the construction process.

Table 1. Inspector responsibilities for typical bridge foundation construction (FHWA/NHI 2022).

| No. | Foundation Types | Typical Inspector Responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spread footings |

|

| 2 | Piles |

Before driving piles

|

| 3 | Drilled shafts |

|

| 4 | Micro-piles |

Prior to the beginning of installation

|

For superstructure erection, proper bracing during construction is crucial for ensuring safety. Bracing can include permanent bracing shown on the drawings as well as temporary bracing necessary until the deck is complete or the diaphragms are installed to connect the girders together (FHWA/NHI 2022). Table 3 summarizes typical inspector responsibilities for typical bridge construction superstructures.

Competencies of Construction Inspectors

This section discusses competencies for general construction inspectors, but the discussion is appropriate for bridge construction inspectors. Effective bridge construction inspection requires technical KSAs specific to bridges. The American Public Works Association (2019) has stated that construction inspectors should possess KSAs in testing, measurement, inspection, documentation, planning and management of job site inspections, and soft skills. There are various core competencies required of construction inspectors to perform their inspection responsibilities. NCHRP Research Report 1027 (Harper et al. 2023) classifies these competencies into four groups: (1) academic, (2) technical, (3) personal effective, and (4) workplace competencies. The competencies found in academia consist of KSAs acquired in educational environments, usually through K–12 education and higher learning. Technical competencies pertain to the specific KSAs required for carrying out construction inspection responsibilities. Personal effective competencies encompass KSAs that reflect an individual’s personal qualities. Workplace competencies involve the general KSAs necessary to fulfill essential job responsibilities (Harper et al. 2023). Table 4 contains definitions of each competency associated with these four groups.

Table 5 shows the relationship between these four types of core competencies and three levels (i.e., entry, intermediate, and advanced) of construction inspection positions. NCHRP Research Report 1027 (Harper et al. 2023) outlines a comprehensive framework for categorizing construction inspectors into three distinct levels based on their experience and qualifications:

- Entry-level construction inspectors: Individuals at this level typically have 0 to 3 years of inspection experience. They are often new to the field and work under direct supervision, handling responsibilities that align with their limited experience in construction inspection.

Table 2. Inspector responsibilities for typical bridge substructure construction (FHWA/NHI 2022).

| No. | Substructure | Typical Inspector Responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abutment |

|

| 2 | Concrete pier |

|

| 4 | MSE wall |

|

Table 3. Inspector responsibilities for typical bridge superstructure construction (FHWA/NHI 2022).

| No. | Substructure | Typical Inspector Responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bearing installation |

|

| 2 | Superstructure erection |

|

| 3 | Bridge deck |

Preplacement phase

|

- Intermediate-level inspection positions: With 4 to 8 years of inspection experience, professionals at this level are expected to have similar educational backgrounds as entry-level inspectors. However, they are required to have accumulated a more substantial amount of hands-on experience and must take on additional responsibilities reflecting their heightened expertise.

- Advanced-level positions: Individuals at this level possess extensive experience in inspection, with over 8 years of practical knowledge and expertise in the field. A high school diploma is typically the lowest level of education needed. To move up to an advanced-level position, intermediate-level inspectors may be required to obtain a college degree in addition to their experience. This reflects the advanced nature of their responsibilities and the depth of their expertise in construction inspection.

Table 4. Definitions of construction inspector core competencies (adapted from Table 3.2 of Harper et al. 2023).

| KSA | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Academic Competencies | Computer skills/digital literacy | Able to use required technologies or computer-related tools and applications |

| Critical and analytical thinking | Analyze, evaluate, question, and interpret information | |

| Basic math | Perform basic calculations using mathematical principles such as arithmetic and algebra | |

| Advanced math | Perform more complex calculations using mathematical principles such as geometry and trigonometry | |

| Reading/literacy | Understand and interpret written information presented in work-related documents | |

| Science | Apply scientific rules and methods to conduct tests and solve problems | |

| Written communication | Clearly communicate important information to others in writing | |

| Oral communication | Clearly communicate important information to others through oral discussions | |

| Technical Competencies | Construction materials | Able to identify and manage work associated with materials (e.g., compile existing sign inventory, guard rail inventory, materials designated for salvage, materials designated for reuse, materials found on a project for use) |

| Construction means and methods | Knowledge of construction materials, means, and methods and ability to apply knowledge when inspecting | |

| Construction scheduling | Understanding project master schedules and progress schedules | |

| Contract requirements | Able to understand contract requirements associated with the work and the requisite experience with the work to be an effective inspector | |

| Inspecting and testing | Able to inspect, test materials, and document work | |

| Plans and specifications | Able to understand and use the project plans and specifications for inspections | |

| Performance measures | Knowledge and application of developing, tracking, and reporting performance measures | |

| Project development | Knowledge of the project development process | |

| Quality control/quality assurance | Knowledge of quality control and quality assurance principles | |

| Regulations, policies, and procedures | Understanding and applying agency regulations, policies, and procedures | |

| Risk | Knowledge of risk identification and analysis | |

| Safety | Knowledge of construction safety and the ability to recognize unsafe situations at the job site | |

| Surveying | Knowledge of surveying and working with surveyors | |

| Tools and technologies | Able to use appropriate tools and technology to perform and record the work, including cameras, videos, tablets, and smart applications | |

| Verification | Able to perform and verify project controls, alignment, layout, and beam profiles using appropriate tools and technology [e.g., total station, GPS, lidar (light detection and ranging)] | |

| Personal Effectiveness Competencies | Adaptability and flexibility | Exhibit the capacity to adapt to changing conditions on a project effectively |

| Dependability and reliability | Exhibit the traits of being responsible and accountable at work | |

| Desire to learn | Demonstrate the willingness to learn new information for performing inspections, as well as problem solving and decision-making | |

| Initiative | Exhibit the willingness to work | |

| Integrity | Be honest with and respectful to others | |

| Interpersonal skills | Demonstrate skills to work with others from various backgrounds and the ability to work through issues and conflicts efficiently | |

| Leadership | Influence and guide others to improve efforts and achieve goals | |

| Professionalism | Demonstrate adherence to the accepted code of conduct for the job | |

| Workplace Competencies | Attention to detail | Meticulously perform inspection tasks |

| Building relationships | Develop and maintain collaborative relationships within the agency and with external organizations that can provide assistance and support | |

| Check, examine, and record data | Transcribe, record, and maintain information/data in written or electronic format | |

| Expectation focus | Setting goals and achieving desired outcomes | |

| Following directions | Perform work diligently based on the instruction and management provided | |

| Planning and organizing | Use logical and systematic processes to achieve goals; prioritize workload to ensure meeting of deadlines | |

| Problem solving and decision making | Able to identify the cause and effect of problems; analyze existing information to develop appropriate and sound decisions/solutions | |

| Teamwork | Demonstrate skills to work efficiently as a team and be aware of others |

Table 5. Core competencies for construction inspection (adapted from Table 3.3 of Harper et al. 2023).

| Competencies | Entry Level | Intermediate Level | Advanced Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academic | Reading literacy, basic math, oral communication | Entry-level competencies plus written communication, advanced math | Intermediate-level competencies plus critical and analytical thinking |

| Technical | Plans and specifications | Entry-level competencies plus inspections and testing, contract requirements | Intermediate-level competencies plus quality control/quality assurance, regulations and policies |

| Personal Effectiveness | Integrity, desire to learn, initiative, professionalism, dependability and reliability | Same as entry level | Intermediate-level competencies plus leadership |

| Workplace | Following directions | Entry-level competencies plus check, examine, and record data | Intermediate-level competencies plus planning and organizing |

Bridge Construction Inspection Training

The main purpose of training is to provide construction inspectors with sufficient KSAs to perform effective bridge inspections during construction. It should be noted that some parts of this section discuss training practices and resources and types of training for general construction inspectors, but the discussion is appropriate for bridge construction inspectors.

Types of Training

State DOTs have used different methods for training their construction inspectors. NCHRP Research Report 1027 (Harper et al. 2023) notes that formal training typically involves a structured learning environment within an academic setting. This comprehensive approach encompasses various modalities, such as traditional classroom-based instruction, hands-on training under the guidance of an instructor, and interactive online training sessions led by an instructor. Formal training is particularly essential for equipping new hires and existing staff with the specific KSAs required to successfully contribute to a highway construction project (Harper et al. 2023). Important factors in formal training are discussed in the following:

- It is important to create a clear and organized training plan that outlines the necessary progression of training.

- The training program should cover both technical skills and professional development.

- Different training programs should be developed for laboratory and field inspectors due to the differing competencies required for these roles.

- Subject-matter experts (SMEs) should be involved in delivering the training content.

- Regular updates should be made to training programs and materials.

- Trainers should also receive training (Harper et al. 2023).

Online training offers flexibility and eliminates the need for instructors and attendees to travel. According to NCHRP Research Report 1027 (Harper et al. 2023), state DOTs have been employing online training methods to cover essential aspects of construction inspection. However, it is important to note that online training has its limitations, particularly in replicating hands-on applications and field experience, which are integral components of construction inspection training.

NCHRP Research Report 1027 (Harper et al. 2023) indicates that the on-the-job training (OJT) approach involves practical, hands-on experience in the field, where experienced trainers provide instruction and support. During OJT, a construction inspector gains practical experience by conducting real-time inspections on an active construction site. This immersive learning

approach allows inspectors to apply their training directly to the challenges and complexities of real-world construction projects. The primary advantages of an OJT approach are that it:

- Allows inexperienced inspectors to observe and learn from experienced inspectors, enabling the transfer of inspection knowledge from seasoned inspectors to trainees;

- Allocates sufficient time to mentor the trainee;

- Takes into consideration the amount of work and the type of tasks involved; and

- Enhances the expertise, capabilities, and skills of seasoned inspectors to provide more effective guidance to trainee inspectors (Harper et al. 2023).

The self-paced learning/training method enables inspectors to acquire new knowledge by progressing through self-guided training materials (Harper et al. 2023). For instance, GDOT has developed a voluntary, self-paced training approach for its construction inspectors (Marks and Teizer 2016). There are nine training modules for GDOT’s self-paced training: (1) general provisions, (2) auxiliary items, (3) construction erosion control, (4) earthwork, (5) bases and subbases, (6) pavements, (7) bridges, (8) minor drainage structures, and (9) incidental items. Figure 5 shows an overview of GDOT’s self-paced training on the bridge construction inspection module.

Table 6, adapted from NCHRP Research Report 1027 (Harper et al. 2023), summarizes the main challenges of construction inspection training and strategies to overcome these challenges. It should be noted that not all of these challenges apply to bridge construction inspection training.

Table 6. Challenges in construction inspection training (adapted from Harper et al. 2023).

| Challenges | Strategies |

|---|---|

| Scheduling conflicts | Provide condensed, just-in-time training sessions at easily accessible locations and self-paced learning to reduce the time required to complete the training. Deliver instructor-led virtual training in the evenings and on weekends. Use downtime and nonconstruction periods for training. |

| Lack of staff resources | Utilize self-paced learning. Use instructor-led virtual training that can be provided to many inspectors simultaneously with limited staff. Schedule annual boot camps when staff are available (e.g., nonconstruction season). Use retirees as SMEs to develop and deliver materials. |

| Lack of funding | Provide training online to reduce the costs and time to attend the training. Provide practical tools and materials for self-paced learning. |

| Lack of time to plan and organize training | Provide condensed and self-paced training programs that reduce the time required to organize and plan the training. Use boot camps that take place at the same time annually to reduce planning and organizing. |

| Lack of accessible training locations | Partner with local training centers and higher education programs. Use of instructor-led virtual training that is provided evenings and weekends. Use downtime and nonconstruction periods for training requiring travel, and have state transportation agency cover travel costs. |

| Low interest or enrollment | Require training for inspectors rather than relying on them to attend. Provide incentives and clear progression possibilities to entice attending training that is not required. Clearly advertise and promote upcoming training options. |

| Lack of communicating training events | Determine a schedule of training events and clearly communicate the plan to inspectors regularly and at least 8 weeks before the scheduled training. |

| Low-quality training | Maintenance of the training program by reviewing training materials regularly and revising as needed. Use of performance measures to know if the training was effective or not. |

| Lack of incentive | Develop training programs that are tied to career paths and promotions so that inspectors are encouraged to attend training. |

Training Resources and Practices

State DOTs typically rely on SMEs to develop and deliver construction inspection training materials (Wight et al. 2017; Mitchell et al. 2016). SMEs are staff experienced in specific content areas who are DOT employees or are hired from a third-party consultant firm. State DOTs are also using experienced retirees with field presence as SME trainers (Dylla and Hansen 2019). SMEs play a crucial role in addressing any recognized knowledge gaps in the foundational content by providing essential resources and information. Their responsibilities also encompass the development, review, and approval of training materials to ensure the accuracy of content. Additionally, SMEs are tasked with delivering the training. Previous publications by Wight et al. (2017), Islam et al. (2017), and Mitchell et al. (2016) highlight a historical preference among state DOTs for having in-house SME trainers handle the development, maintenance, and delivery of training curricula.

State DOTs heavily use construction manuals and standard specifications for bridge construction inspection training. NCHRP Research Report 1027 (Harper et al. 2023) states that while these documents are helpful resources for training construction inspectors, they are sometimes difficult to use in the field. Several DOTs (e.g., New York, Minnesota) have achieved success by creating dedicated web pages and using various social media platforms to offer comprehensive training resources for their inspectors. The following sections briefly discuss sample DOT bridge construction inspection training practices.

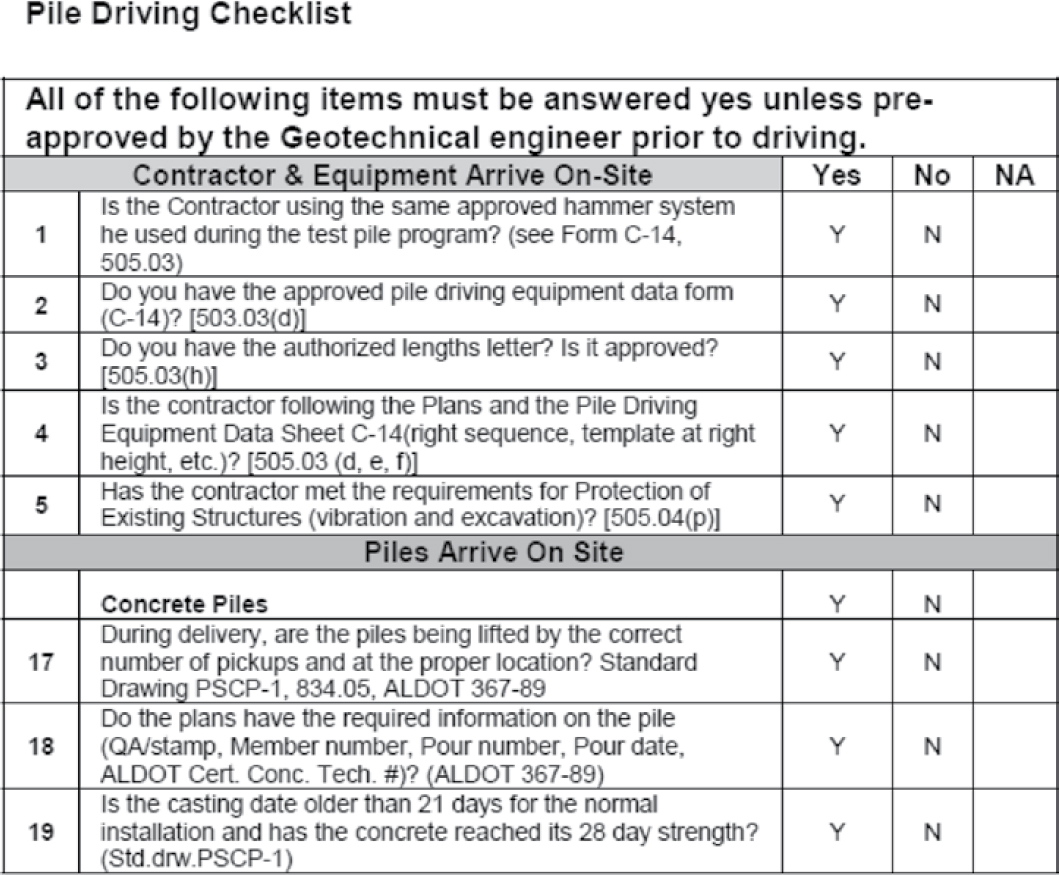

Alabama DOT’s Bridge Construction Inspection Training

The Alabama DOT (ALDOT) has used the Bridge Construction: Hip Pocket Guide for bridge construction inspection (ALDOT 2008). The guide was designed for field use. The guide contains various essential checklists and construction forms to aid the inspector during the various

stages of construction. The checklists and forms focus on the most important issues of bridge construction during field inspection and include:

- Working drawings checklist,

- Environmental policy,

- Bridge foundation construction,

- Pile-driving inspection checklist,

- Drilled shaft inspection checklist,

- Bridge substructure construction,

- Bridge superstructure construction,

- Anchor bolt checklist,

- High-strength bolt checklist,

- Field welding inspection checklist, and

- Field painting inspection checklist.

Figure 6 shows a sample of the pile-driving checklist. ALDOT (2008) emphasized that the guide is intended as a convenient reminder of the most important items, and it is not a replacement for their full manual.

New York State DOT’s Bridge Construction Inspection Training

The New York State DOT (NYSDOT) has a series of videos for bridge construction inspection, including for basic construction inspection, bridge deck inspection, pile-driving inspection, bridge painting inspection, and construction safety training for construction inspectors. For example, under basic construction inspection, the training video covers the following topics:

- Role in the department

- Role in the field

- Typical day

- How to interact with the public

- How to address media inquiries

- How to work with the contractor

- Available contract resources

- Department electronic resources (NYSDOT 2020).

Under bridge deck construction inspection, the training video covers the following topics:

- Inspection staff preparation

- Advance preparation

- Preplacement meeting agenda

- Dry run (This covers all necessary checks and verification related to bridge deck construction.)

- Placement day

- After the placement

- Inspectors’ duties

- Deck pour reference materials.

Under pile-driving inspection, the training video covers the following topics:

- Pile types

- Splicing piles

- Toe treatments

- Pile coating

- Pile-driving hammers

- Pile-driving leads

- Methods of starting piles

- Pile testing

- Safety

- Pile inspection

- Communication and forms.

Additionally, NYSDOT provides a series of construction inspection checklists for bridge construction:

- QC [quality control] Checklist—Bridge Deck Concrete Placement

- QC Checklist—Pile Installation

- QC Checklist—Structural Steel Painting

- QC Checklist—MSE Wall Inspection

- QC Checklist—Cofferdams.

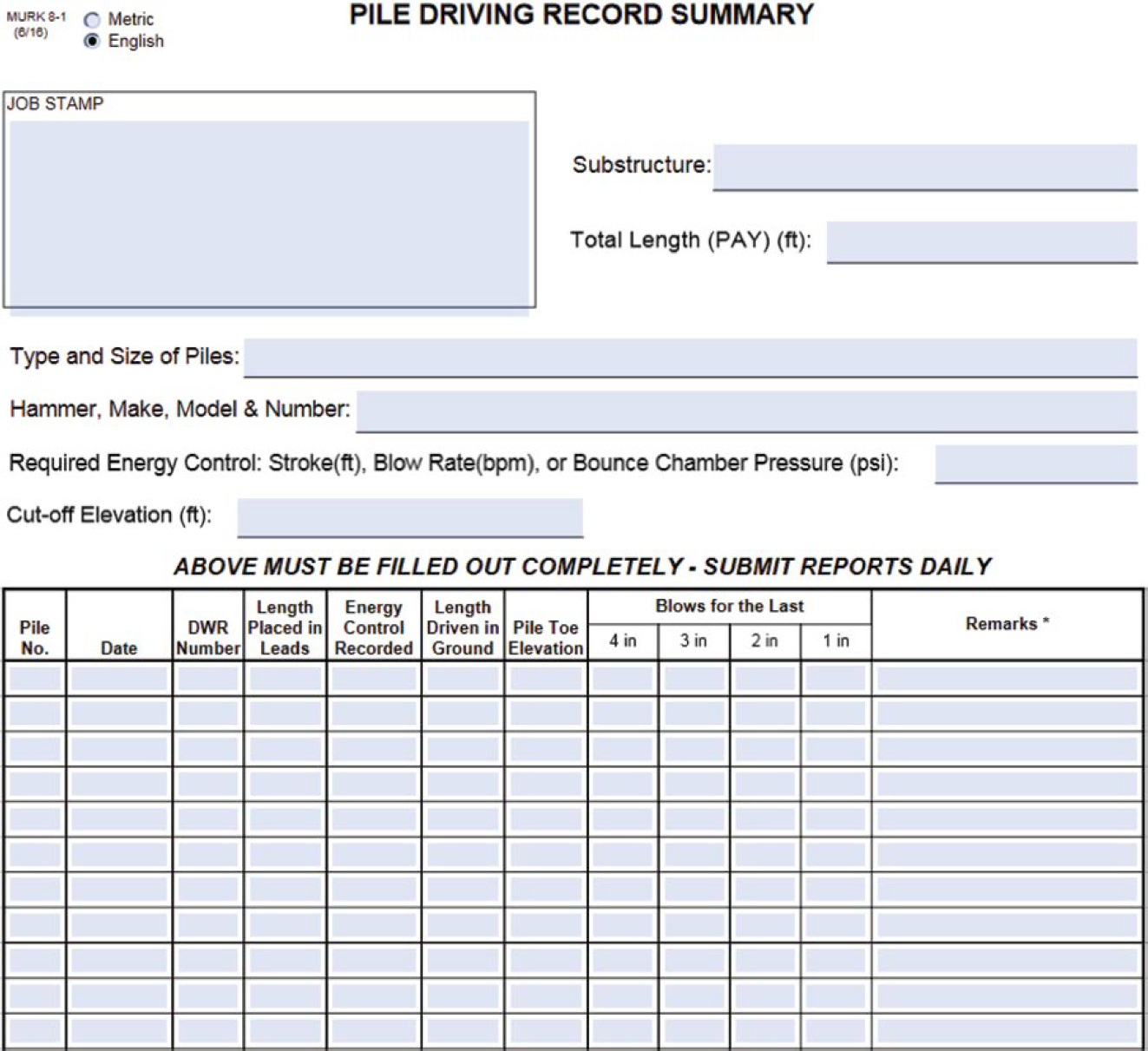

NYSDOT also provides a series of construction inspection forms. Figure 7 shows a sample of the pile-driving record summary form.

Minnesota DOT’s Bridge Construction Inspection Training

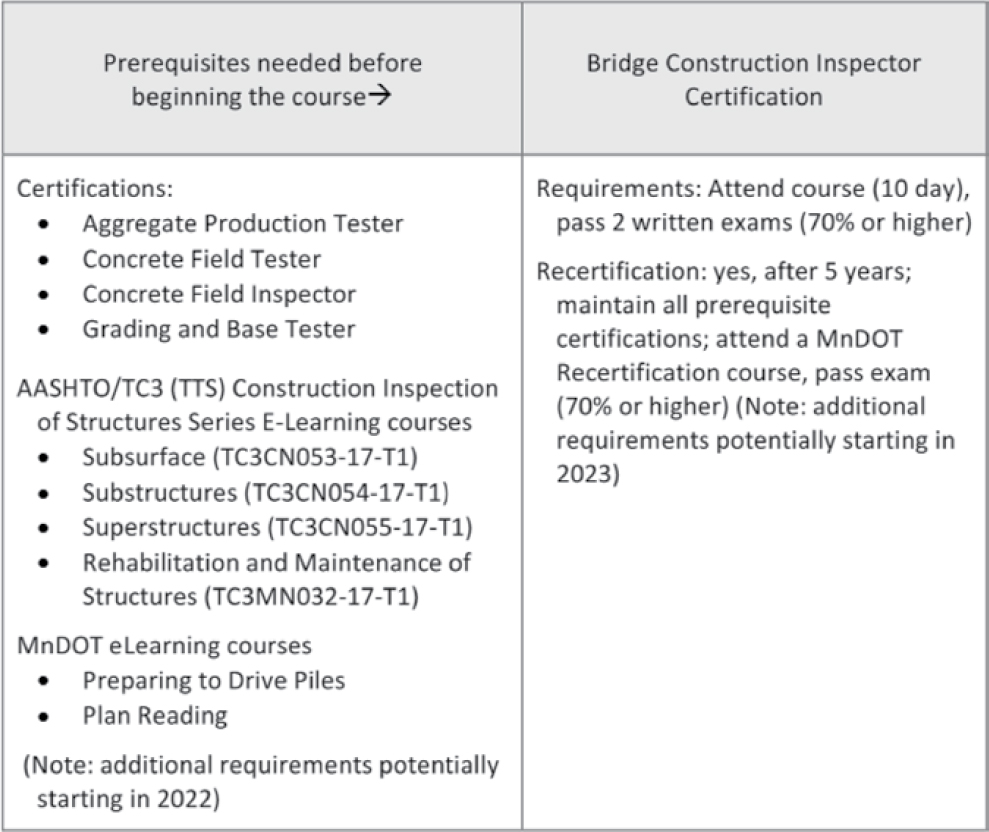

The technical certification program at the Minnesota DOT (MnDOT) has offered several courses for bridge construction inspectors. These training courses are developed and taught cooperatively by technical experts from MnDOT, private industry, and educational institutions. To attend bridge construction inspector courses, MnDOT requires participants to be certified as Aggregate Production Testers, Concrete Field Testers, Concrete Field Inspectors, and Grading and Base Testers. Participants are also required to take MnDOT e-learning courses and AASHTO/Transportation Curriculum Coordination Council (TC3) Construction Inspection of Structures Series E-Learning courses. Figure 8 summarizes the requirement for bridge construction inspector certification.

The MnDOT e-learning courses include:

- Introduction to pile driving; bridge foundations,

- Preparing to drive piles,

- Driving test and foundation piles, and

- Plan reading.

The AASHTO/TC3 Construction Inspection of Structures Series E-Learning courses include:

- Subsurface (TC3CN053-17-T1)—This course gives an overview of the underground and foundation-related aspects of structures that require monitoring and inspection during construction.

- Substructures (TC3CN054-17-T1)—This course offers an overview of substructures and essential inspection components, particularly those that provide support for the girders or beams of the superstructure deck, such as abutments, bents, and piers.

- Superstructures (TC3CN055-17-T1)—The course offers an overview of superstructures and the critical inspection components, focusing on the section of the structure located above the substructure.

- Rehabilitation and Maintenance of Structures (TC3MN032-17-T1)—This course covers important inspection components for rehabilitation and maintenance and addresses technical details for expert understanding.

- Reinforcing Steel for Structures (TC3MS064-21-T1)—This course provides in-depth coverage of the production process and material characteristics of reinforcing steel before it is delivered to the construction site.

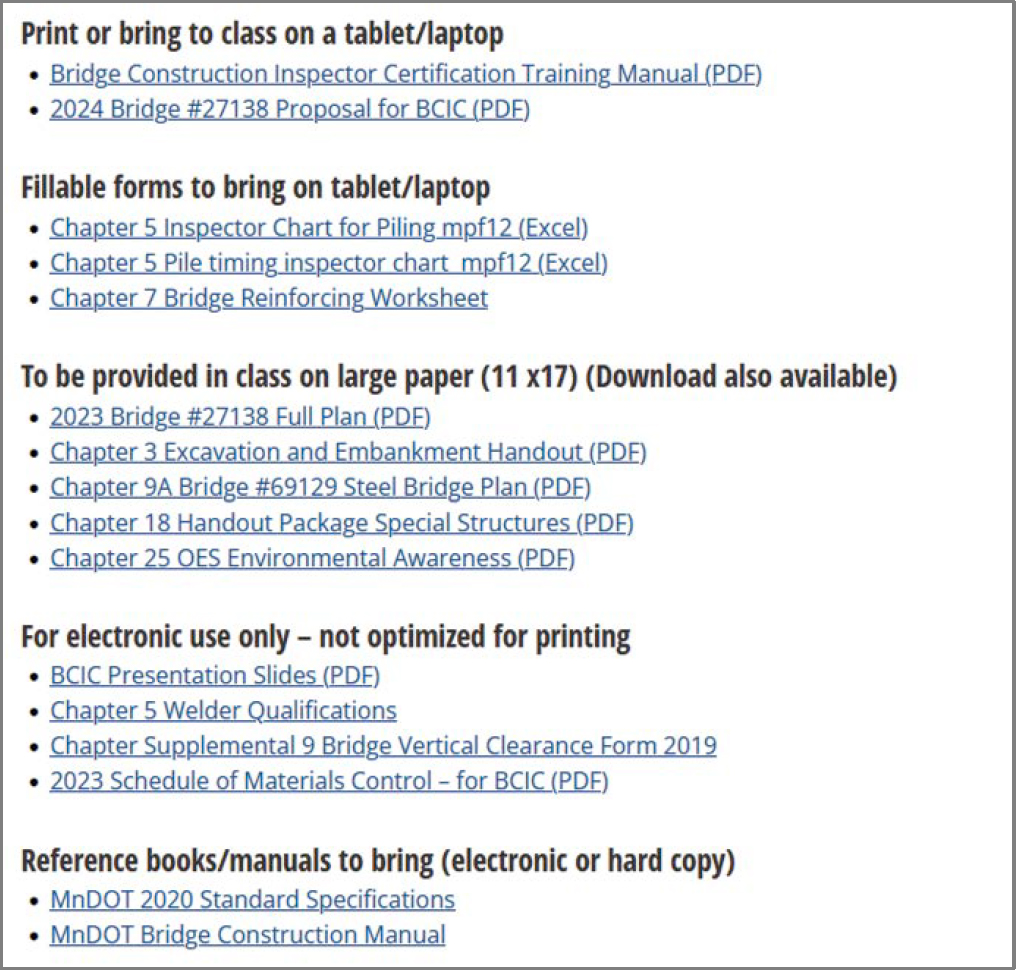

Additionally, MnDOT provides a series of training resources for bridge construction inspectors, including MnDOT bridge construction manuals and MnDOT standard specifications. Figure 9 shows a snapshot of MnDOT bridge construction inspection training resources.

Career Advancement of Bridge Construction Inspectors

This section mainly discusses career advancement for general construction inspectors, but the discussion is appropriate for bridge construction inspectors. Career development is a process that involves the advancement of individuals through various stages in their professional lives. This progression not only benefits individuals by helping them grow and achieve their career goals but also benefits the organization by ensuring that employees are skilled, motivated, and able to contribute effectively to the overall success of the agency. According to NCHRP Research Report 1027 (Harper et al. 2023), it is more efficient and cost-effective for state DOTs to retain and develop in-house inspectors rather than to be constantly recruiting and training new inspectors. The career advancement of bridge construction inspectors is contingent upon their capacity to acquire new KSAs while enhancing their existing ones. Table 7 summarizes the main resources for state DOTs to help bridge construction inspectors advance their knowledge and skill sets.

Note: BCIC = Bridge Construction Inspector Certification.

Table 7. Resources for bridge construction inspectors to maintain and advance their career path (adapted from Table 5.3 of Harper et al. 2023).

| Resources | Remark |

|---|---|

| Standard specifications | Usually only for reference due to the length. Important for inspectors to know how to use them when needed. |

| Construction manuals | Expounds on specifications and standards to provide guidance and techniques for construction inspections. |

| Guidelines, technical reports | Short and easy-to-read documents. Designed for online availability. |

| Training/mentoring | Develop an informal or structured training and mentoring program. Evaluate potential mentors from within the DOT to ensure involvement. Explore non-agency and third-party consultant mentors. |

| Memorandums | Communicate time-sensitive information. Maintain a database of past memorandums to ensure applicability. |

| Staff meetings | Provide opportunities to gain feedback on construction inspection topics. Meetings with district/regional leadership and statewide conference with all in-house inspectors. |

It should be noted that standard specifications and construction manuals are typical documents for bridge construction inspectors across all state DOTs. Some state DOTs (e.g., Alabama, Georgia, and Wisconsin) have specific guidelines or technical reports for construction inspectors to inspect a bridge during construction. Some state DOTs (e.g., New York, Texas, and Minnesota) also have various training resources for bridge construction inspectors. Other resources for bridge construction inspectors to keep up with current key knowledge and skill sets include mentoring programs, memorandums, and staff meetings.

When construction inspectors leave their employment, state DOTs face several negative impacts. These include lost investments in training, the depletion of valuable experience, the loss of critical skill sets, and the additional costs associated with finding and training a replacement. The career development of a bridge construction inspector is influenced by a variety of factors, including their abilities, skills, level of experience, personality traits, geographical location, and personal needs. NCHRP Research Report 1027 (Harper et al. 2023) provides a set of suggested practices for state DOTs to retain and develop career paths for construction inspectors (see Table 8).

Although the practices in Table 8 were developed for general construction inspectors, they are appropriate for enhancing the bridge construction inspection workforce. The building partnerships practice involves actively promoting and fostering cross-system partnerships with local, state, and federal programs, as well as with colleges, universities, and construction organizations. These partnerships are critical in ensuring effective and comprehensive bridge construction inspection processes (Marks and Teizer 2016). By engaging with the industry, state DOTs can effectively pinpoint the KSAs required as well as any existing gaps. This allows them to verify competencies and tailor training programs specifically for bridge construction inspectors.

Table 8. Practices for state DOTs to retain and develop construction inspection workforce (adapted from Table 5.6 of Harper et al. 2023).

| Recommended Practices | Description |

|---|---|

| Develop construction inspector series of positions | Develop a series of technical/inspection positions. Many state DOTs use detailed employment series for engineering positions, and those processes can potentially be used to develop technician series for inspection positions and career development. |

| Build partnerships | Build cross-system partnerships with local, state, and federal programs as well as colleges, universities, and construction organizations to develop successful construction inspector-focused education and training initiatives. Partnering with local community colleges and 4-year institutions allows experts to help provide the education and training necessary for promotions. Using available local expertise and building relationships with higher education provide more resources to state DOTs to educate and train their inspectors. |

| Connect with the industry | Stay connected to the contracting industry and service providers to identify KSA needs and gaps, validate competencies, and customize training as needed. |

| Provide awareness of technological innovations | Build awareness of technological innovations to enable construction inspectors to develop new skills. |

| Form co-ops with higher education | Consider forming co-ops with higher education and other external training and certification organizations, where state DOT staff provide the training while using the institution or organization’s resources and facilities. |

| Provide internal agency programs | Form internal agency programs to grow construction inspectors through mentoring and shared learning. These programs can also show the value of inspectors to other divisions and departments in the agency. |

| Help inspectors track their careers | Have construction inspectors take hold of their careers by tracking their work and experience and providing evidence (e.g., portfolio) to management that shows that an inspector is worthy of a promotion. |

Summary

The literature review findings outlined in this chapter document the key areas in which training and qualifications for the bridge construction inspection workforce are essential. The primary objective of this chapter is to offer an in-depth comprehension of the resources and methodologies employed in training for bridge construction inspection. The responsibilities of inspectors in the realm of bridge construction inspection, as well as the core competencies (also known as KSAs) necessary to effectively carry out bridge construction inspection, were discussed in detail. Additionally, the various resources, tools, and types of training used in bridge construction inspection, along with the opportunities for career advancement available to bridge construction inspectors, were presented.