Practices for Transportation Agency Procurement and Management of Advanced Technologies (2025)

Chapter: 9 Case Study for Electronic State Transportation Improvement Program

CHAPTER 9

Case Study for Electronic State Transportation Improvement Program

Case Study Summary

This case study involves RIDOT migrating from an analog, largely manual State Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) to an electronic STIP (e-STIP) solution.

From a procurement perspective, this case study is unique in that the technology acquisition was conducted without an RFP process; rather, the state transportation agencies involved in the case utilized a series of single-source partnerships along with in-house development to accomplish the needs. Indeed, some specialized technology uses lack market solutions and require consultant support rather than competition to achieve a solution.

Despite lacking an RFP process, this case still presents many lessons learned about deploying a new enterprise-wide technology that can be useful to other DOTs that may utilize an RFP approach. In many instances, a new technology project requires unique procurement approaches that substantially differ from those used for engineering, construction, and maintenance projects.

This scenario would apply to future DOTs that have identified a need for an advanced technology for which no suitable existing market solutions exist that can meet their requirements. Although rarer, the development of a single-source approach can be successful in such cases, but it does come with substantial planning, market research, legal work, and procurement justification.

Multiagency Coordination

The e-STIP system was a coordinated effort of three agencies as well as the centralized IT group:

- RIDOT Division of Planning: RIDOT is responsible for the state’s highway network, including bridges, pavement, safety, pedestrian and bicycle facilities, and stormwater systems for the roads. RIDOT is also responsible for some of the state’s ferries, including the seasonal Providence to Newport ferry and commuter rail transit facilities in Rhode Island.

- RIPTA: RIPTA serves as the statewide transit provider that offers fixed-route buses, paratransit, flex zones, and commuter services.

- Rhode Island Department of Administration’s Division of Strategic Planning (RIDSP): RIDSP coordinates and compiles the program of projects RIDOT and RIPTA put forward to develop the STIP (alongside other transportation plans). RIDSP develops the text and analysis portion of the STIP. RIDSP is also responsible for actively seeking public participation during the STIP public review and adoption process. RIDSP serves as staff to the metropolitan planning organization (MPO).

- Division of Enterprise Technology Strategy and Services: The division, under the leadership of the chief digital officer, encompasses the Office of Digital Excellence, the Office of Information Technology, and the Office of Library and Information Services. Its mission is to enable the Rhode Island state government to achieve its goals efficiently and effectively by providing strategic leadership in applying IT.

Purpose, Goal, and Objective of the Project

This project’s goal was the development and configuration of a statewide planning suite (SPS) to facilitate the acquisition of candidate STIP projects from RIDOT, RIPTA, and municipalities.

Current State Environment Prior to the New Technology Procurement

From a STIP project intake perspective, the existing analog project intake process was overwhelming. The existing system was a labor-intensive process for managing transportation investment proposals submitted by municipalities. Municipalities submitted proposals using paper and pen, often physically marking maps with highlighters as part of these submissions. These proposals could involve investments exceeding $100 million. There were also redundant workflows across the agencies that resulted in re-entry of the same data.

Staff members at the MPO faced numerous challenges in handling the manual data inputs, including the need to manually comb through applications, collect notes, and evaluate processes. The data for each proposed project were then entered into a database manually, which further highlights the repetitive and labor-intensive nature of the work. This manual approach led to inefficiencies in data entry and project management, which brought a risk of suboptimal project outcomes.

Despite these challenges, the existing process did contribute to the development of a new 10-year plan that included an asset management approach to meet performance goals. This plan initiated a shift in perspective, viewing projects as “bundles” of multiple projects rather than as isolated initiatives. Yet overall, there was consensus that many aspects of the STIP adoption process needed to be updated from the perspectives of policy, programming, and technology.

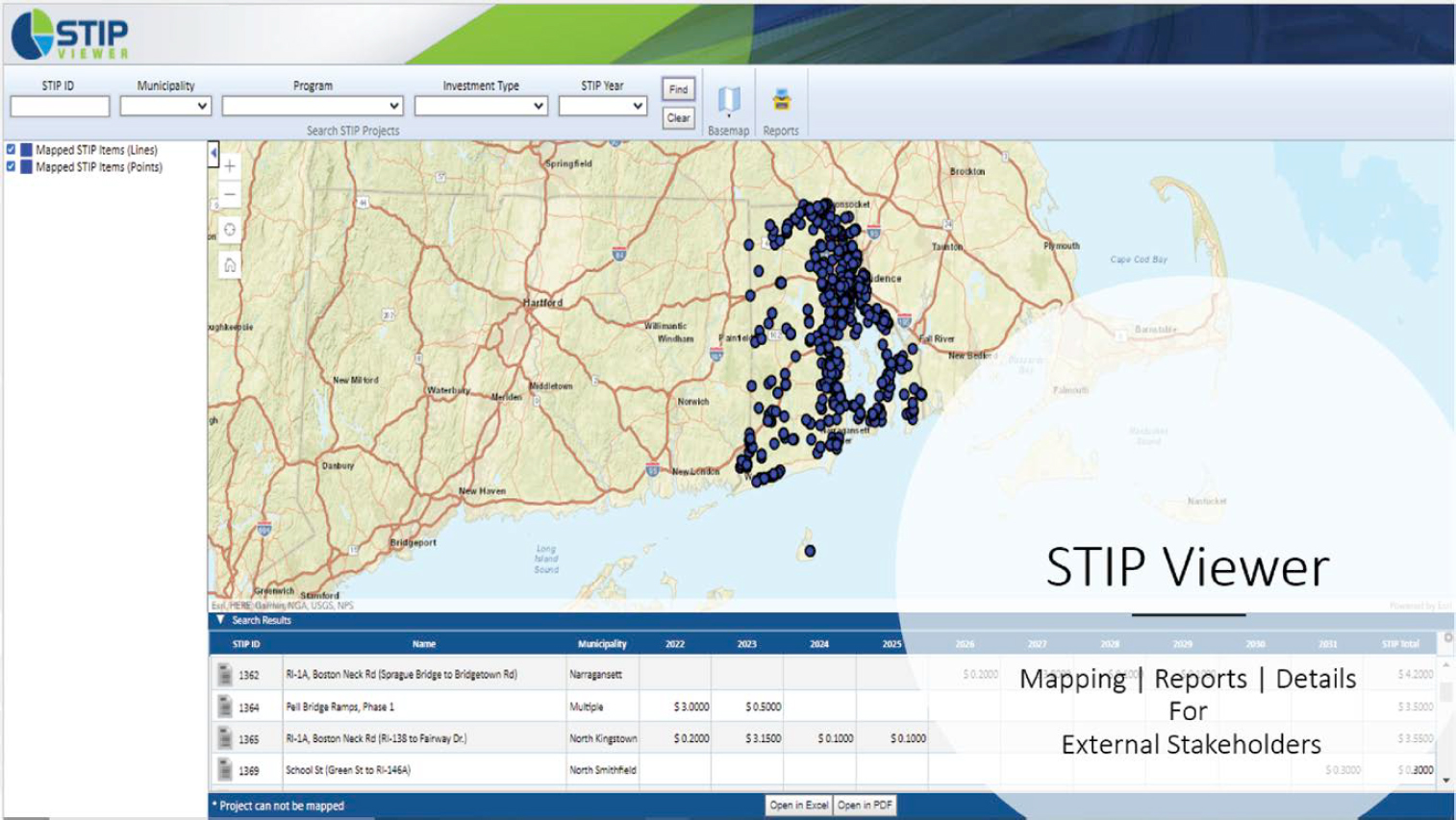

Figure 14 illustrates the conceptual process by which Rhode Island planned to migrate to an e-STIP. The past STIP involved a paper application process that was stored in a local database and enabled the public to view limited project information in an online map. The first major step taken was to utilize the STIP bundler to generate STIP projects in a map-based environment better controlled for cost predictability. The mapping dashboard provided more information than in the past. Looking to the future, the goals for the next STIP were to develop a statewide intake framework for transportation (SWIFT) for STIP project intake, which will ultimately enable better project selection based on a data-driven scoring process. The future state will also use a custom-designed STIP viewer to display the STIP project information in both a tabular and map-based environment.

Market Research Activities

To explore options to transition towards an e-STIP, RIDSP partnered with FHWA to organize a peer exchange with other DOTs in the region who brought experience with a data-driven e-STIP. This event was pivotal in highlighting the gap between leadership’s perception of their current capabilities and the actual situation, as well as the risk of over-engineering the systems.

Key insights from this exchange emphasized the need for robust systems to support an e-STIP, highlighting the importance of establishing clear processes and responsibilities for interpreting and responding to data. It also revealed various methods of incorporating equity into the STIP process, such as transparent project evaluation systems, pre-submission counseling, and community engagement.

Furthermore, the peer exchange stressed the importance of managing municipalities’ expectations through improved processes and technology, such as comprehensive gap analysis. Balancing thoroughness with efficiency in designing STIP processes was identified as a critical challenge.

The state also partnered with the GIS mapping software firm ESRI to develop a framework for the e-STIP suite of applications. The envisioned capabilities of the e-STIP solutions include realizing goals from the Long-Range Transportation Plan, facilitating project acquisition from various stakeholders, supporting performance-based planning with standardized tools, reducing recurring STIP amendment activities, and generating economies of scale by bundling projects.

In summary, the state learned about technology options on the market through collaborative peer exchange and partnership with experienced agencies and a GIS software firm.

The peer exchange and surrounding efforts to canvas the marketplace for out-of-the-box solutions revealed that none of the existing products met the state’s needs. Therefore, the state was faced with the struggle of determining which set of vendors, tools, and technologies would need to be utilized to develop the necessary e-STIP system.

Future State

The state ultimately implemented multiple initiatives in parallel, including:

- A contract was executed with an external vendor to manage public comment intake, multiagency coordination on the response, and then output to the STIP public comment report.

- RIDOT developed the STIP bundler in-house. The agency placed all assets in a map-based environment to much more easily identify projects to feed the STIP. The map-based environment also made it easier to bundle assets into STIP projects when doing so made geographic and contracting sense and would achieve greater cost savings (e.g., generate economies of scale in project execution by identifying two or more individual projects for bundling into a single super project). The bundler also enabled the state to spot conflicts in projects.

- The state worked with an external vendor on the development of SWIFT for STIP project intake. The focus of the solution was to approve STIP projects based on data-driven analysis and criteria.

- A separate vendor was brought in to implement STIP manager software to manage the financials associated with the STIP and publicly display the STIP via map viewer tools. The focus was to manage the funding, schedule, reporting, and amendments of approved STIP projects created through the SPS. Figure 15 shows a sample of the custom-developed STIP viewer.

Single-Source Justification

To enable contracts with external vendors who would develop the intake solution and STIP manager software, separate “single-source” justifications were compiled. The justification was compiled as a joint effort of RIDSP and RIDOT and reviewed by the Division of Enterprise Technology Strategy and Services. There were several key aspects to the single-source justifications, which are described in the following (note that the actual process could perhaps be better termed as a “limited source” justification, given the competitive nature of selecting the software vendor and implementation partner):

- The prior relationships of the separate vendors were reviewed. In this instance, separate vendors were required to work together and integrate seamlessly to develop the necessary applications. A proven track record of two vendors having worked together in the past was established in the justification.

- Based on the considerations discussed, the software provider (responsible for the development and configuration of an SPS) was selected via the DOT’s Master Price Agreement (MPA), which was already on file. The MPA was established via an open competition posted to the Bid Board administered by the State of Rhode Island Division of Purchases (State of Rhode Island, Division of Purchases, Department of Administration n.d.). The justification for using this specific software firm was based on the prior item (proven track record of working with implementation firms for similar scopes) along with their pricing information that was already on file with the DOT.

- The software provider noted two implementation companies for the DOT’s consideration. The DOT received quotes and reviewed demonstrations from the two competing vendors. The following information was evaluated between the two:

- – Initial quotes for implementation services,

- – Forecasted costs for annual maintenance,

- – Status as a DBE/Women’s Business Enterprise (WBE),

- – History of implementing similar solutions in bordering DOTs, and

- – Review of sample systems provided by each firm.

Upon reviewing this information, the selected implementation partner was justified due to their superior evaluation in every category (cheaper upfront and annual costs, status as a WBE, demonstration of more robust sample systems, and more relevant experience in bordering DOTs). All this information gathered in a competitive arena was substantiated to justify the selection of this vendor to incorporate the approved STIP projects into a centralized database.

The implementation partner was contracted via a separate agreement from the software vendor. This was because the software provider cannot resell third-party software; therefore, any products, technology, or software solutions that may be added by the implementation partner could not be subcontracted under the software provider. One downside of this approach is that the DOT takes on greater responsibility for coordination between two entities under separate contracts.

Challenges Encountered and Lessons Learned

There were many findings that may be valuable to future DOTs who undertake a similar program or even use an RFP approach. The following highlighted findings are organized by procurement phase.

Pre-Solicitation Phase

- A healthy amount of background research and legwork was performed before the agencies solidified the actual needs and intended outcomes. Many of the project requirements were driven by formal reporting needs at the state and federal levels.

- There was a robust review protocol from the state’s Division of Information Technology for cybersecurity and resource-planning perspectives. A major effort was undertaken to ensure the project would not put any data at risk or cause issues when redundancies in the current state were being eliminated (this was conducted before the project was approved to proceed into procurement). This concern was in part due to the largely manual legacy procedures, which would be centralized into a single database. Another aspect of the concern was justifying the single-source approach, in that cybersecurity personnel wanted to ensure the source’s system was fully compliant with all security requirements. There was also a substantial focus on determining whether dedicated servers would be needed to run the future state system. The Division of IT was involved from the initial planning stages of the project and was instrumental in the review of the single-source justification early on.

- The agencies noted that it would have been helpful to possess a clearer understanding of who should be on the project team from the beginning. For example, key team components included:

- – GIS experts who understood the DOT’s terminology and had a background in data storage and data management.

- – Representatives from roads/highways specialties, ArcGIS-Pro specialists, etc.

- – Adoption of a testing lead from each agency. The project team asked them to put together a master spreadsheet of the scenarios tested and the outcomes being sought in each scenario.

- – Ideally, a dedicated IT project manager to run point during implementation would have been present. The DOT in this instance felt that the implementation vendors often “spoke a different language” than the DOT’s in-house engineers and planners. At times, the DOT sensed that the vendors did not fully understand what the DOT’s engineers and planners needed. Therefore, an IT project manager (or similar resource) would have been helpful to act as a “translator” throughout the implementation efforts.

- Gaining approvals to proceed with a tailored solution strategy was important. From a cost–benefit perspective, perhaps the most impactful information in gaining executive approvals was quantifying the pain of the current state (in particular, there was a recent event wherein a major amendment in the STIP required roughly 7 months of manual effort to process, which pulled staff time away from other initiatives). Another helpful justification was noting that other DOTs were already undertaking similar initiatives.

Single-Source Procedures

- Single-source contracting encountered a lengthy contracting duration.

Post-Solicitation Phase

- Deployment of an enterprise-wide solution was difficult while other live systems ran in parallel. At first, the vendor would complete an integration and notify the DOT to give feedback, which resulted in DOT staff conducting independent reviews. A major flaw in this initial process was the lack of direction regarding what the DOT should look for when testing new integrations. The DOT and their vendors continually had to compare iterations. For each process improvement implemented, dedicated tracking of reference points was required for testing and iteration. Eventually, a master tracking system was compiled in spreadsheet format to document each scenario that was tested and what outcome was being sought. Each scenario was iterated in a test environment until staff felt it was accurate. Finally, guides were developed to help other staff and public users learn to use the final tools.

- The agencies learned that software companies and their staff speak a different language than transportation engineers and planners. The task of helping the software and other vendors understand the agencies’ needs was a consistent challenge that required dedicated resources.

- In terms of long-term life-cycle management of the new system, the agencies must now retain the services of these vendors and technology providers for the long term. This is an important consideration in single-source procurement scenarios, wherein the resulting technology solution is somewhat custom-built. Managing vendor relationships in this scenario can be difficult because there is less opportunity to expose the vendors to competition and test the market from other providers; rather, in a single-source scenario, the vendors may help build the system from scratch or in a highly customized manner, and the DOT will pay a maintenance fee depending on what that solution ends up becoming. Furthermore, all future upgrades and enhancements must go to the same vendors.

- Among the most important aspects of gathering requirements is fully documenting the current state environment concerning data. During implementation, the agencies found that the vendors unanimously wanted to know where the existing data were located and where they needed to go in the future state. Ideally, this information should be a priority to document during requirement-gathering efforts in the pre-solicitation phase. Other useful information to document includes master diagrams and workflows.