Practices for Transportation Agency Procurement and Management of Advanced Technologies (2025)

Chapter: 1 Introduction and Background

CHAPTER 1

Introduction and Background

The primary aim of this research project was to establish a comprehensive guide that will assist state departments of transportation (DOTs) in enhancing their procurement practices for new transportation systems technologies. The guide is designed to achieve three key objectives: First, it aims to identify successful procurement practices that align with industry standards. Second, it seeks to outline procurement processes that are sufficiently flexible to accommodate the rapid pace of technological advancements. Lastly, the guide endeavors to provide sustainable strategies for information technology (IT) and procurement officials within DOTs to effectively implement and evaluate these procurement processes.

The procurement and management of advanced technologies present unique challenges that differ significantly from those encountered in engineering and construction services. This process involves acquiring both the technology itself and associated services, including deployment, training, and support. Such procurements have a broader impact on DOT internal operations, as these new solutions need to be seamlessly integrated into the existing technology infrastructure. The range of solutions varies from ready-to-use “out of the box” options to highly customized developments, where integration with other existing and future systems is a critical factor for success.

This industry is relatively new and rapidly evolving, in contrast to the more established construction sector. It poses greater difficulty in developing technical specifications compared to the conventional engineering design process. Additionally, these projects must cater to a wide array of user groups, such as system owners, custodians, procurement, administrative staff, and others, making the process more complex and multifaceted.

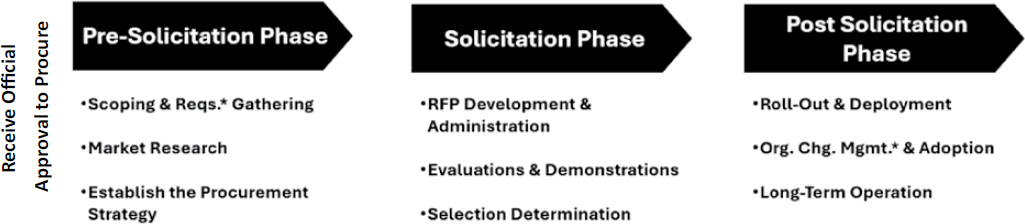

As shown in Figure 1, the life cycle of a technology project is typically segmented into three critical phases, which begin with the official approval to proceed to procure a technology. The first, the pre-solicitation phase, involves initial solicitation preparations such as scoping, requirements gathering, and conducting market research. Following this, the solicitation phase encompasses the development and administration of the request for proposal (RFP), the evaluation of submissions, demonstrations from vendors, and ultimately, the selection of the appropriate technology solution. The final phase, post-solicitation, is focused on the roll-out and deployment of the technology, managing organizational change and adoption, and ensuring the long-term operation and maintenance of the system. Each of these phases is pivotal in ensuring the successful procurement and implementation of new technology projects within DOTs.

Challenges in the Pre-Solicitation Phase of Technology Projects

The pre-solicitation phase of technology projects requires substantial planning. Past studies have shown that the seeds of problems are often sown early in the project life cycle. A survey of 600 U.S. business and IT executives (Geneca 2011) revealed startling figures: 75% believed

Figure 1. Life cycle of a technology project.

their projects were doomed from the start, and 80% spent at least half their time on rework due to unclear objectives, confusion over roles and responsibilities, and insufficient stakeholder involvement. Furthermore, another study on early warning signs of technology project failure identified the “Dominant Dozen” risks, which were predominantly people- and process-related, rather than technological (Kappelman et al. 2006). This suggests that proper training and tools are crucial for increasing the probability of success of technology projects.

Challenges in the Solicitation Phase of Technology Projects

The solicitation process for new technologies is fraught with challenges. First, the procurement process itself can vary across different types of technology more than is the case with procurements with which DOTs are more familiar, such as engineering, construction, and facilities projects (Johansson and Lahtinen 2012; Jørgensen 2006; Moe et al. 2017). In this environment, new technology procurements necessitate many important decisions and points of definition in the solicitation process itself, including, but not limited to, a clear definition of requirements, functionality and use cases, implementation timelines, and evaluation criteria and weights (Hassan et al. 2018; Nguyen et al. 2021). Technology procurement decisions, especially in the context of new software, have the potential to be highly influenced by sales and marketing information put forth by technology providers, which in turn can set unrealistic expectations within the client organization about the level of scope, functionality, and reliability that each vendor can ultimately achieve (Ibrahim et al. 2013).

Challenges in the Post-Solicitation Phase of Technology Projects

After the RFP activities are completed and a technology vendor is contracted, the challenges shift towards successful deployment, adoption, and maintenance of the technology. The Standish Group, after analyzing three decades of technology project performance, found that 26% of IT projects fail (either canceled or unused after implementation), and 46% face challenges such as budget overruns, delays, and reduced features (Johnson 2020). Moreover, a study by McKinsey and the University of Oxford on 5,400 technology projects highlighted an average cost overrun of 66% and a schedule overrun of 33%, with larger projects tending to perform worse (Bloch et al. 2012). These findings underscore the complexity and risk inherent in managing technology projects, especially in their later stages.

Data Collection

Data collection for this project was executed through three primary methods to ensure a comprehensive analysis. Initially, 75 examples of advanced technology RFPs were gathered from various DOTs to scrutinize the nuances of procurement strategies, timelines, evaluation metrics, and specific requirements, with the aim of creating an accessible digital repository of RFPs and scopes of work (SOWs). Concurrently, a collaboration with the Center for Procurement Excellence (CPE) allowed for engagement with a network of procurement professionals across multiple state procurement offices, leveraging their collective experience in handling a high volume of IT procurements to understand the procurement landscape from their perspective. Lastly, thorough interviews with personnel from DOTs, spanning approximately 1 hour each, provided in-depth insights from different functions, including procurement, contracts, information technologies, and various user groups, thus covering a broad spectrum of perspectives from traffic to program management and beyond. The study’s primary data sources are shown in Figure 2.

The following state transportation agencies (STAs) and municipalities were interviewed:

- California Department of Transportation (Caltrans).

- Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT).

- Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT).

- Idaho Transportation Department (ITD).

- Maine Department of Transportation (MaineDOT).

- Maryland Department of Transportation (MDOT).

- Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT).

- New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT).

- New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT).

- Rhode Island Department of Transportation (RIDOT).

- Rhode Island Public Transit Authority (RIPTA).

- South Carolina Department of Transportation (SCDOT).

- Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT).

- Texas Department of Information Resources (TxDIR).

- City of Detroit, MI.

- Mohave County, AZ.

- Pima/Maricopa County, AZ.

- Nashville Department of Transportation (NashDOT).

Note that multiple interviews were conducted with each agency to focus on differing topics and to gather many perspectives.