Practices for Transportation Agency Procurement and Management of Advanced Technologies (2025)

Chapter: 3 Pre-Solicitation Phase

CHAPTER 3

Pre-Solicitation Phase

Overview

This chapter is a compilation of tools and best practices related to the pre-solicitation phase of technology procurements. Its content was derived from a combination of the following:

- Collaboration with the CPE to adapt several existing procurement tools for specific applications to transportation technologies.

- Interviews and discussions with procurement professionals who are members and associates of the CPE.

- The research team’s collective experience procuring advanced technologies across the public and private sectors.

- Transportation-specific input from roughly two dozen interviews with DOTs and other transit authorities conducted as a part of this study.

This chapter is organized into three sections of narrative content to describe best practices for the pre-solicitation phase of technology procurements. These sections include:

- The importance and critical elements of the SOW.

- The importance and critical elements of documenting the current state environment.

- Other tips and lessons learned for documenting the SOW and current state.

Pre-Solicitation Phase Tools for Practitioners

Five tools to assist DOTs in the pre-solicitation phase of their technology procurement efforts are also included in the appendices. A brief explanation of how to use each tool is given in this report; however, because the tools contain various file types (Word, Excel, PDF), the individual tools are provided as separate files so that they can be directly used in their native file format. The list of tools includes:

- Appendix A: SOW Assessment. A tool that can be used to grade/score/assess the quality of an SOW for any technology-related project. The scoring system is defined within the template and follows the five critical elements of a highly effective SOW for technology projects. The one-page tool is intended to be brief and highly usable across a broad range of technology types.

- Appendix B: Template for SOW for Technology Implementations. A detailed template to assist DOT project teams in developing their SOW for new technologies. The 11-page template includes step-by-step instructions and examples for each of the five critical elements of a highly effective SOW.

- Appendix C: Template for Mandatory Requirements. An Excel-based template for tracking mandatory requirements on an item-by-item basis. This template coincides with the SOW template in Appendix B.

- Appendix D: Template for Desired Requirements. An Excel-based template for tracking desired requirements on an item-by-item basis. This template coincides with the SOW template in Appendix B.

- Appendix E: Template for Current State for Technology Implementations. A detailed template to assist project teams in documenting their current state environment prior to procuring a new technology.

Project Intake and Early Planning

The integration of the concept of operations (ConOps) tool, as used by MaineDOT, is essential to highlight. This tool has been identified by the research team as a pivotal element in the planning and execution of transportation projects. The ConOps is a strategic planning document that facilitates the transition from traditional, outdated systems to contemporary, integrated solutions. It provides a comprehensive blueprint, delineating the project’s purpose, essential requirements, and operational procedures. This high-level overview is instrumental in shaping the functionality of new systems. Crucially, the ConOps is integral to the development of RFPs, ensuring a streamlined and effective project implementation process. This is particularly valuable in scenarios involving accelerated timelines or other challenging conditions. Furthermore, the ConOps aids in identifying potential gaps and areas requiring future research, thereby maintaining alignment with the overarching research objectives and ensuring a coherent and forward-looking approach to project planning.

Refer to Appendix L for a template example of a ConOps document that is based on input from MaineDOT, MnDOT, and others.

Another aspect of an effective project intake process is to remind internal project teams to review state or agency guidelines on data, software, and other technology-related policies. Each state or agency may have different governing policies related to the early planning of new technologies, especially related to justifying the need for new technology, planning for how new technology will be integrated into the current technology environment, cybersecurity protocols, and more. Early review of existing guidelines will result in a more efficient and effective procurement process that minimizes potential surprises downstream.

Funding Considerations

Another point of pre-solicitation planning occurs when DOTs decide to use federal funds from the U.S. Department of Transportation through the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the Federal Transit Administration (FTA), or the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA). The FHWA, FTA, and FRA each provide federal funds based on the actual mode (or modes) of transportation (highways, transit, or rail) that the DOT operates and maintains.

Through the procurement process, DOTs may acquire various commercially available technology goods and services in compliance with the federal funds they receive to complete advanced technology projects. DOTs are permitted to use their own procurement procedures that reflect applicable state and local laws and regulations if those procedures conform to the procurement standards of the government-wide Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards, under 2 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) §§ 200.314 through 200.326 (National Archives n.d.-a).

Additionally, if federal funding is used for intelligent transportation system (ITS) projects provided by FHWA, the regulations under 23 CFR Part 940 must be followed for the procurement of ITS technologies (National Archives n.d.-b).

Another consideration is the Build America Buy America Act, which was enacted as part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 (Office of Acquisition Management n.d.). There are also acknowledgments of prohibited platforms, which restrict foreign sources of technology (U.S. Department of Transportation 2024).

DOTs are responsible for adherence to maintaining their own procurement standards in the settlement and satisfaction of all contractual and administrative issues related to contracts entered in support of the federal funding awarded or allocated. This includes disputes, claims, protests of awards, source evaluation, or other matters of a contractual nature. Other responsibilities include:

- Ensure contractor integrity and compliance with federal laws and regulations.

- Maintain records of the procurement and contracting process.

- Ensure Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (DBE) participation is addressed.

- Checking the System for Award Management for debarred and suspended contractors (U.S. General Services Administration n.d.) and referring to suspension and debarment FAQ provided by the US General Services Administration (U.S. General Services Administration 2024).

There are also considerations for the size and type of procurements when using federal funds. For example, fair and reasonable procedures shall be used for all procurements not exceeding the simplified acquisition threshold of $250,000 (or lower if state or local laws have a lower threshold). Contracts secured under the simplified acquisition procedure must still document that the DOT took actions to ensure that it is receiving the best price for the services/goods purchased (e.g., document three separate price quotes and justify why one was chosen). Contracts exceeding $250,000 need to go through a formal competitive bidding process.

Furthermore, if a DOT is conducting a sole source procurement, it must follow the same policies and procedures it uses for procurements from its non-federal funds under 2 CFR § 200.317. Sole source procurements are conducted by noncompetitive proposals, wherein the solicitation of a proposal is from only one source.

Additional information related to procurement guidance when leveraging federal funds can be found at:

- FHWA: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/bipartisan-infrastructure-law/guidance.cfm (FHWA n.d.).

- FTA: https://www.transit.dot.gov/funding/procurement/procurement (FTA n.d.).

Defining the SOW

The SOW outlines the technology requirements that a DOT’s project team aims to procure from technology providers. The SOW might also include or be referred to by various terms, such as “specifications,” “minimum qualifications,” “functional requirements,” “business requirements,” and “security requirements.” However, irrespective of the terminology, the SOW serves as the backbone during the pre-solicitation phase, providing a clear directive for the DOT project team and potential technology providers. A draft SOW should be completed before conducting market research.

Timing for SOW Development

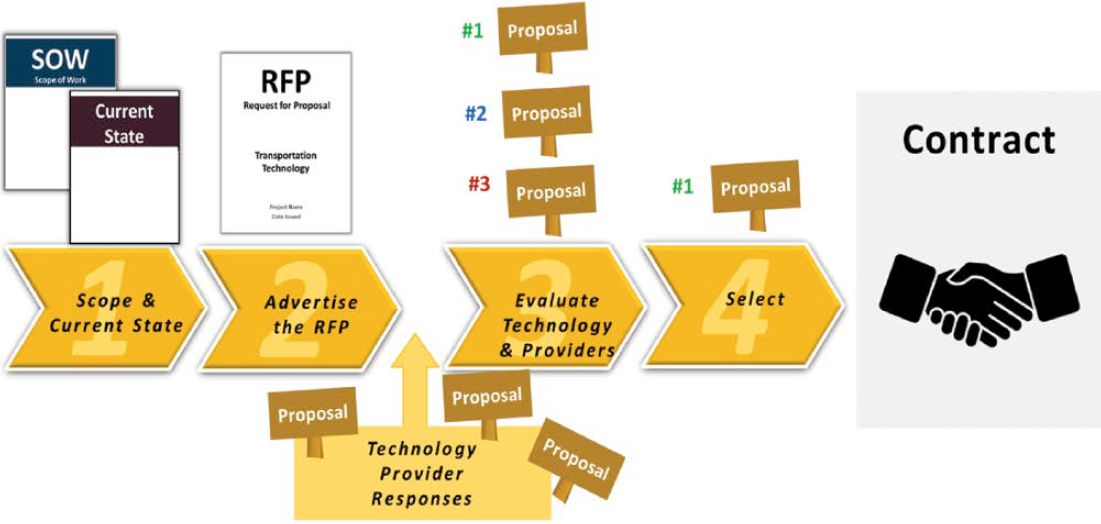

Establishing the SOW and the current state of affairs should precede the release of the RFP. Figure 3 depicts the general sequence of events that is preferred for most technology procurements. It is not uncommon for organizations to prematurely engage in discussions with technology providers or initiate requests for quotes prior to finalizing their SOW. A premature engagement

typically consists of user groups extending invitations to individual vendors to conduct demonstrations, presentations, meetings, and/or other direct engagements but without the formal support, guidance, and supervision of procurement and contracting staff. This misguided sequence of activities tends to result in confusion and inefficiencies.

Conversely, market research processes are to be conducted in coordination with appropriate procurement and contracting staff. This enables more formal and centralized tracking of the outreach and engagement of external vendors before the eventual solicitation. Further, there are established market research techniques such as a request for information, pilot-level RFPs, and others that can be facilitated with the involvement of procurement professionals. Finally, the involvement of procurement professionals can also ensure that market research activities are openly advertised to the entire marketplace (which avoids giving the false impression of favoritism if only certain known vendors were engaged).

Developing a comprehensive (or at least a draft-level) SOW prior to market research interactions facilitates a systematic approach, ensures all project needs are accurately identified, and fosters alignment among stakeholders. Furthermore, proper procurement protocol typically requires or strongly prefers that discussions with external technology providers about their products and services be conducted in a formal and organized process with the full knowledge, support, and guidance of the DOT’s procurement professionals. Figure 3 shows the major activities during the RFP (see Figure 1 for the overall phases).

Significance of the SOW

The SOW is a pivotal document that equips technology providers with the necessary information to consider the project and develop a robust proposal. Inadequately prepared SOWs may lead to reduced competition, wide pricing ranges, and poor-quality proposals, as vendors may find the SOW unachievable or unfair (see Figure 4). Poor SOWs may also result in vendors submitting generic, marketing-heavy proposals and assigning less competent teams to the project. All these impacts can result in a greater probability of scope gaps, change orders, and dissatisfaction during the post-solicitation technology roll-out.

When crafting the SOW per optimal practices, the DOT’s project team specialists need to adopt the viewpoint of the technology providers submitting proposals for the project. To accomplish this, it is advisable to pose the following key inquiries:

- What type of data would be beneficial for technology providers to submit their most competitive and precise pricing?

- Which specific information will assist technology providers in devising a reliable plan and timeline for implementation?

- How can we reduce the potential for assumptions, ambiguities, and unnecessary precautions?

- What information will enable technology providers to submit their best price with minimal contingencies?

- What is the most important information that should be included in the SOW?

Critical Elements of the SOW

The SOW should incorporate more than just a list of itemized requirements. It should also address the DOT’s overall objectives, use cases, project parameters (e.g., budget, schedule), and the current state of technology within the organization. Here are the key components:

-

Overview and purpose of the project. This section, kept to a maximum of 1–2 pages, should include a brief description of the project and the underlying motivations behind it. This section serves as a brief “pitch” or “promotional message” to draw the attention of prospective technology vendors. It should succinctly explain the “what” and “why” of the project (“what” technology is being acquired and “why” the DOT is initiating this project).

- – The project summary should provide a high-level outline that is accessible to the layperson (someone who is not a technical specialist in the DOT’s project team or knowledgeable about the technology in question). This is crucial because most technology providers have non-technical administrative personnel who will sift through new RFPs and assess whether the project aligns with their company’s capabilities. Bearing this audience in mind, the project overview should be devoid of technical lingo, jargon, intricate details, and specifics; instead, think of this section as a quick advertisement to catch the attention of the technology provider community.

- – The project goals, aims, and impetus should succinctly relay the key business incentives and intent of the project. Put simply, why is the DOT’s project team keen on this project? What will constitute a successful outcome in the coming years? This information becomes

- a guiding beacon for technology providers as it allows them to tailor their proposal and strategy around the client’s fundamental objectives.

- – Understanding the fundamental “why” behind their client’s projects is always of great value to technology providers. Indeed, many technology providers affirm that this insight is more useful than an exhaustive list of itemized prerequisites from clients. Offering a lucid description of the project goals, motivations, and anticipated outcomes acts as a guiding beacon for the technology provider community, typically leading to superior proposals that are custom fitted to the specific needs of the DOT’s project team group.

- – Reduction in pending jobs, missing reports, etc.

- – Completion of pending tasks.

- – Decrease in reporting discrepancies.

- – Improved efficiency in task delegation.

- – Similar objectives.

-

Future state. This element outlines how the DOT envisions the use of the technology upon implementation, from user interactions to legacy data incorporation. The future state section is designed to articulate how the DOT’s project team foresees the application of the technology once it is in place. This section, for instance, should detail:

- – Which user groups are anticipated to engage with the technology and how?

- – How will the technology ideally interact with other facets of the client’s tech ecosystem?

- – Which historical data will be transferred and utilized with the new technology?

- – The anticipated basis of pricing and corresponding quantities is crucial to ensure that proposals are comparable in a “like-for-like” manner, to the greatest extent feasible. Pricing requests are best matched to the providers’ pricing schemes; for example, some software packages may be priced based on the total number of employees, specific user counts, various measures of data volumes, and so forth. When DOTs request pricing from technology providers, there is less chance of confusion when the pricing request is matched to the providers’ known pricing structure; however, emphasizing this aspect of technology procurements may be different than what DOTs have historically used for non-technology sectors (where the pricing schemes are often more consistent and well known).

-

Itemized requirements. A well-organized list of technology requirements (functional, business, technical, security, etc.) is essential. The requirements should be categorized into mandatory and desired elements, as follows:

- – Mandatory requirements are treated as pass/fail items which are the minimum expectations of the technology provider or their technology. In other words, the proposing technology provider and their product(s) must meet every mandatory requirement. Failure to meet any individual mandatory requirement will result in automatic disqualification of the technology provider. Therefore, mandatory requirements should not be overly burdensome in such a way that unnecessarily constrains competition.

The DOT project team can achieve this by articulating a clear problem they wish to resolve. What is the business motivation behind this effort? What is the necessity and objective of the new technology? This information is generally simpler to document than the granular specifics within a requirements list. In essence, outlining the overall purpose can prove more beneficial for technology providers than supplying minutely specific data around functional, technical, business, security, and data requirements.

In drafting the SOW, the most beneficial step a DOT’s project team can take is to outline your needs from a bird’s-eye view. What will the technology do for you? What results do you wish to achieve? For instance, the expected outcomes from a computerized maintenance management system could encompass:

- – Desired requirements are where the value proposition of each technology provider will truly shine. The client’s goal is to achieve as many of these requirements as possible. However, technology providers will not be disqualified for missing one of the desired requirements. Typically, the technology providers who can meet the most desired requirements will be front-runners in the evaluation process.

-

Schedule and budget. The RFP should provide a clear picture of the project’s schedule and budget constraints. This information helps standardize proposals from various vendors.

- – Schedule constraints should describe the anticipated duration of the implementation or deployment phase. This helps to set a benchmark for all competitors to propose to, which will give a more comparable representation of costs (and does not prohibit technology providers from providing alternative proposals for more rapid or more conservative deployment capabilities). The DOT should also clearly identify any phasing considerations; for example, do certain requirements or functionalities need to be delivered before others? Also, the client should identify whether a legacy system will be decommissioned at a particular time.

- – Budget constraints are an important way to clarify the client’s needs and what they can reasonably afford. The best practice is to provide a clear and direct budget in the RFP, ideally publishing both the budget for one-time up-front costs as well as ongoing annual budgets for licensing, support, and long-term operation. For example, the RFP may include a statement such as, “The project budget is $3,000,000 over 5 years, of which $500,000 is allocated for implementation and $500,000 for annual subscription and support.”

-

Unique considerations. This section should consider the technology provider’s point of view. What might be unique or unusual about the DOT’s specific needs vs. the technology provider’s other customers? One example would be to define the type of legacy data that the technology provider must handle. Other important information includes any unknowns or assumptions built into the SOW. The client should directly identify these items and, wherever possible, provide a reasonable benchmark for technology providers to include in their proposals (which keeps the proposals comparable across the technology provider pool).

Identify any areas of the scope that are not well-defined or well-known. A best practice is to openly identify these items and ideally provide a reasonable benchmark or “guesstimate” for providers to use in their proposal.

Providing an assumed quantity or definition for unknown items is better than omitting these items, for two reasons:

- – First, identifying these items ensures the proposals will be compared equally because providers will not miss or overlook the information.

- – Second, providing a reasonable benchmark will minimize guesswork or other contingencies the providers may add to their pricing to cover the unknowns.

Finally, it is important to show that the DOT has resourced a dedicated project team and will make subject matter experts available to support the project.

Be aware that introducing additional categories or definitions of requirements is not advisable. Shy away from other classifications of requirements that are “nice-to-have” or “on roadmap.” Such categories may only be advisable in the largest, most complex projects that span the entire DOT enterprise and represent tens of millions in annual spending. Instead, for most technology projects, focus on the two categories of mandatory vs. desired, and simply discard the rest. This will lead to a more succinct, precise enumeration of itemized requirements that genuinely capture the core priorities of the DOT’s project team.

Critical Elements of the Current State Environment

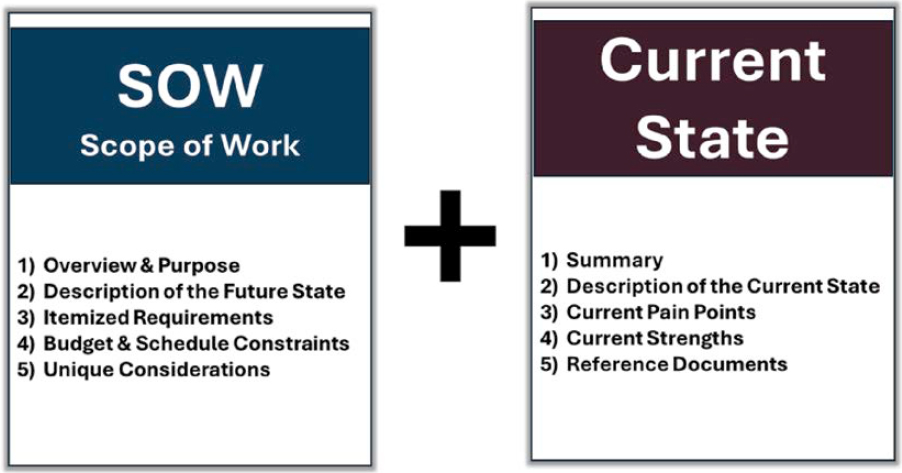

The “current state” serves as an instructional guide encompassing crucial aspects pertaining to the DOT’s existing environment that will be impacted by the project. This includes a definition of the legacy system(s), if any. This section should also cover the operational environment that currently exists and make use of the current technology or legacy system. The current state information will eventually be included in the RFP document alongside the SOW. As shown in Figure 5, the SOW and current state work together within the RFP. Their combined purpose is to “paint the picture” for prospective technology providers regarding the DOT’s future need vs. current environment concerning the new technology being solicited.

The Value of the Current State to Technology Providers

The current state often takes precedence over the SOW for technology providers. One reason is that technology providers already have a clear expectation of the future state because it is essentially the specifications of their existing technology (which they already understand in detail). They need to set up their technology to fit the client’s specific environment.

For a technology provider, the client’s existing environment is generally the largest unknown of the entire project and represents their greatest risk. Technology providers are therefore extremely interested in learning about the client’s current state, because it gives them more insight into the environment they would be integrating their technology into.

This current state is a primary consideration for pricing (especially as it relates to the technology implementation or roll-out). As illustrated in Figure 6, implementing technology is akin to navigating from “Point A” (current state) to “Point B” (the future state described in the SOW). The current state’s criticality surpasses that of the future state because it provides a clear starting point, offering foresight into potential roadblocks and challenges in the journey. It is crucial to note that technology providers usually possess a comprehensive understanding of the future state, as it essentially involves deploying their own system specifically tailored to the client’s environment.

In the analysis of technology RFPs from DOTs, the research team reviewed a series of three RFPs issued by a single DOT for deployment of connected vehicle signal phase and timing. The technologies included equipment systems with signal phase and timing encoders/processing

units, roadside unit antennas, power and communications cables, on-board units, specialized tools, and diagnostic software. These RFPs were issued over 4 years for different regions of that state. One noticeable change across the three RFPs was that the issuing DOT included increasingly greater detail on the existing configuration requirements.

Five additional reasons are provided to further explain why the current state is so critical to project success:

- Comparative analysis. Facilitates a more effective comparison between technology provider proposals due to a mutual understanding of the project’s starting point.

- Realistic approaches. Allows technology providers to design feasible strategies for transitioning from the current state to the future state.

- Team alignment. Provides a clear understanding of the required skill sets, enabling technology providers to assemble the most suitable team to meet client-specific needs.

- Efficiency. Each day spent gathering these data pays dividends throughout the implementation phase.

- Accuracy. If the client fails to gather this information, the technology provider will need to do so at a later stage, consuming additional time and resources and potentially leading to less accurate data.

In summary, the inclusion of explicit, concise, and comprehensive information on the current state significantly increases the probability of selecting the most suitable system and technology provider team. Therefore, the current state should be thoroughly documented and considered an indispensable part of the technology implementation process.

Common Reasons Why Project Teams Fail to Document the Current State

Multiple justifications exist to which client teams may appeal to bypass the current state analysis. This section reveals the seven most frequently cited reasons and debunks their efficacy as valid grounds for omitting the current state.

- The current state is superfluous as technology providers focus on the future state. To the contrary, technology providers value the current state equally, if not more, than the future state. From their perspective, their task is to guide the client from the current state to the future state. They are already acquainted with their system’s potential future state capabilities, but the current state determines their pricing, planning, resources, and capacity to optimize the system according to the client’s needs. Without insight into the current state, technology providers undertake the deployment without necessary insights.

- Documentation of the current state causes providers to propose a “rip-and-replace” of the legacy system, which is not what the DOT wants to achieve. In reality, documenting the current state does not necessarily imply an exact replication of the legacy system in the new system. The current state is a launching point, and the future state requirements, which can deviate from the current state as desired, should also be defined. Irrespective of the future state’s goals, technology providers need to comprehend the client’s current state, which establishes the baseline of the project.

- Current state disclosure reveals constraints, which can invite greater change orders and cost additions during the project. The reality is that every challenge, gap, and constraint will eventually incur costs; they cannot be neglected or evaded. The crucial question is whether the client would prefer to competitively price the best approach to tackle these challenges or negotiate each one individually during project execution under pressure. Opting for competitive pricing promotes innovation and reduces change orders, delays, and associated distress.

- Outsourcing current state documentation to the technology provider is more cost-effective. Some project teams will cite how busy they are as a reason for not documenting the current state. They may also say that the selected technology provider is best suited to help the DOT in capturing the current state information because the provider has more experience in implementing the new technology type. Though feasible, this scenario favors the technology provider financially and devalues the client’s ability to document their system. Technology providers cannot match the client’s accuracy in documenting the current state. The effort to provide access to the current states still requires significant client resources. Furthermore, omitting the current state from the RFP process will result in the competing providers making different assumptions in their pricing and project approach, which will ultimately favor the provider who takes the greatest risk in omitting contingencies.

- Absence of a legacy system means the current state cannot be documented. This case can entail the presence of existing programs, data, processes, workflows, and staff, even without a formal technical system. For such instances of manual and home-grown environments, the current state’s documentation becomes even more crucial. Due to the unfamiliarity of technology providers with the specifics of the DOT’s home-grown environments, omitting the current state leads to greater uncertainty, risk, and increased contingency in the technology provider’s pricing.

- Insufficient time for current state documentation. The current state will eventually need documentation, either now or later. If deferred, the technology provider’s lack of familiarity may lead to longer documentation time. The question arises: should the technology provider be billing during this process? Or can the DOT capture the current state more cost-effectively (while likely also doing a better job)?

- Irrelevance of the current state due to adaptability to the technology provider’s solution. Regrettably, no solution exists that completely disregards the current state. Consider system integration requirements, unique operational aspects, historical data formats, operational needs for dashboards and reports, and specific calculations or functions, all of which denote elements of the current state.

- Addition of a new capability for which the current state does not exist. In some cases, there is no existing system, which can leave agency staff unsure about how to describe the current state. This would be true in the case of requesting all new capabilities; therefore, a current state does not exist, and the agency will be augmenting its current operations with new technology, associated procedures, and integrations. In such cases, the addition of an entirely new capability would require an organizational change effort, wherein agency staff will need training and will experience a learning curve as the new technology is integrated into operations.

In conclusion, the importance of current state documentation is indisputable. Each day spent on its documentation can potentially save multiple days during the implementation phase. The significant payback amplifies the question: Can clients afford to neglect current state documentation?

Critical Elements of the Current State

The documentation of the current state should ideally comprise five primary elements, each providing significant insights to the technology providers, as follows:

- Summary. This element aims to provide a holistic understanding of the client’s current state environment. It should explore whether there is a legacy system to be replaced or whether this will mark the client’s initial venture into implementing this type of technology. If the latter, the current procedures should be detailed. This section should also summarize the participating user groups and their extent of involvement, thereby assisting technology providers in gauging the organization’s technological familiarity. Additionally, it should highlight the current workflows and business practices most likely to change due to new technology.

- Description of the current state. This portion needs to encapsulate further details of the relevant data from the existing environment. This may include the historical number of users of the legacy technology, if any, or the current procedures that the new technology will impact. Also, any pertinent quantities, such as the number and types of existing equipment, assets, and related items, should be documented. Historic volumes of transactions, events, or other activities related to the new technology’s role within the organization would also be beneficial.

- Pain points. This section should outline the most prominent pain points (around five to 10) associated with the current state environment and operations, particularly those related to the new technology. It would be best to provide a succinct, easy-to-understand list that includes each point.

- Strengths: advantages. This segment should shed light on any advantages of the current state that should be preserved in the future state. Information of this nature can underscore the importance of certain functions or applications of future technology, thereby facilitating technology providers in formulating their proposals.

- Reference documents. This last section should incorporate links to additional current state details, which most commonly include architectural diagrams, integration schemas, workflows, use cases, and similar information.

Tips for Developing the SOW and Current State

This section shares several tips to help project teams undertake the process of developing their current conditions and SOW. These are proven practices to overcome the top six greatest challenges in completing the pre-solicitation activities related to the SOW and current conditions.

Tip #1: Always Start by Documenting the Current State

Many practitioner groups can underestimate the significance of portraying their current state environment. Yet, this aspect is a critical determinant for technology providers when they craft precise pricing, schedules, and resource requirements for their services, including implementation, deployment, and associated data migration tasks. If the SOW lacks a clear description of the current state, the technology providers will effectively be navigating without a map in terms of where to start with technology deployment, which inevitably leads to additional contingencies

in their pricing. Also, the client will incur extra costs, as the technology providers must sit with them to glean the necessary current state information. Moreover, the current state heavily influences the deployment timeline. If the client compels technology providers to make assumptions in their proposals, it becomes highly probable that the project will face schedule setbacks and other change orders later.

When a client neglects to include their current state in the RFP, they will surely bear the cost eventually. The chosen technology provider will invariably wish to understand the client’s present operations to ensure their technology is deployed optimally. If the client procrastinates gathering their current state until after the contract has been signed, they compel the technology provider to aid in this effort while their time is being billed—a route that invariably proves costlier than if the client had done it independently. Moreover, remember that nobody comprehends the subtleties of the client organization as well as the client, so assigning this task to a technology provider will invariably result in less accurate outcomes.

Another compelling rationale to start with the current state is that it represents the most straightforward part of the entire scoping procedure. Frequently, project teams can become stuck or delayed when articulating their future state requirements, mainly because the future state can seem more nebulous and might involve novel technology aspects that the team is not yet acquainted with. Nonetheless, the project team is undoubtedly well-versed in the structure of the current state environment, which makes it an ideal starting point to ensure the scoping process does not hit a roadblock at the onset.

Tip #2: Understand the Balancing Act of Overly Prescriptive vs. Too Open-Ended

Perhaps the greatest dilemma when crafting the SOW is determining the necessary information to include and the level of detail required (see Figure 7). Overloading the SOW and current state with excessive information can pose a risk. Presenting an SOW that borders on information overload or that carries overly specific requirements can make it burdensome for technology providers to respond promptly (and may even drive them away from your business altogether). However, being too vague can lead technology providers to incorporate additional contingencies to account for the gaps in the SOW.

The consequences of each extreme in the balancing act are as follows:

Consequences of an overly prescriptive SOW and current conditions:

- Can notably escalate cost and schedule.

- Eliminates the flexibility to suggest strategies and innovations for the specific environment.

- Constrains technology providers in terms of the work and the way it is executed.

- Reduces the level of accountability felt by proposers when they are under contract.

- Brings risk to the project.

Consequences of an open-ended SOW and current conditions:

- Open to interpretation.

- Encourages the minimum.

- Less consistency in pricing (wider range in cost proposals).

- Less competitive pricing (increased contingency).

- Discourages proposers from submitting.

- Brings risk to the project.

The principal objective of the SOW is to offer a clear and reasonable benchmark, allowing technology providers to generate precise pricing and proposals in response to the RFP. A well-defined SOW ensures the cost proposals are directly comparable, akin to parallel comparisons. Therefore, DOT project teams should strive to make this benchmark easy for technology providers to locate and comprehend (and the benchmark should be presented regarding the core cost drivers that technology providers will utilize in formulating their quotes).

Bear in mind that the objective is not to make the SOW unbearably detailed. DOT project teams are advised to adhere to the page restrictions described previously in the sections on the SOW and current state. The SOW simply needs to create a clear image and align with industry norms to facilitate fair competition (see Figure 8). Excessive focus on upfront details can cause proposers to overlook major objectives and bypass crucial background information (current state). Information that may sometimes seem apparent or extraneous is highly beneficial to bidders.

In summary, DOT project teams should seek a clear, concise, accurate, and complete set of SOW and current state documentation. The goal is to avoid the extremes of being overly prescriptive or too open-ended because both scenarios lead to the negative consequences described earlier.

Tip #3: Beware the Potential Politics Around Releasing the Budget (and Schedule)

Perhaps the greatest “political hot button” is whether to publish the project budget and schedule constraints openly. Project teams should be ready to navigate this question along with potential internal pushback against openly releasing this information to prospective technology providers.

The preferred practice from this study is to disclose the budget directly in the RFP. The precise budget should be released, not a rough estimate or a range but the true amount at the project team’s disposal. However, ensure the disclosure is done correctly and by adopting the right procurement procedures.

The thought of releasing the budget initially elicits reservations. However, consider the broader context. The primary concern is the potential exploitation of the disclosed budget by technology providers, who may inflate their prices to align with the budget. But how often does a project budget truly surpass the project scope? Put another way, how frequently does the project team have more money than they need? In most instances, organizations are in the reverse situation, where their budget is inadequate or “tight” for their project scope. This reality implies that the project team frequently asks technology providers for more than the project’s budget can afford.

To help project teams understand the impacts of releasing the budget, evaluate both scenarios: having a constrained budget or having more money than is needed. In each scenario, the pros and cons of releasing vs. concealing the budget are considered.

What are the pros and cons of concealing the budget?

- Downside #1. Concealing the budget deprives technology providers of the opportunity to use their expertise to mitigate the largest project risk—the insufficient budget allocation.

- Downside #2. Concealing the budget inadvertently aids underperforming providers, whose competitive advantage often hinges on their initial low cost. High-performing providers might find it hard to differentiate themselves in such situations, making lower performers appear more attractive in a financially constrained scenario.

- Downside #3. When providers’ estimates overshoot the hidden budget, it often leads to frustration, blame, and even potential project termination. This situation may trigger inappropriate scope reduction, aggressive negotiation, and “value-engineering,” which result in inefficiency and additional expenditure of time and effort.

- Benefit #1. The project is safeguarded against providers inflating their prices. However, if the project is already working on a tight budget, this advantage is moot because there is not enough money to support the original scope, let alone inflated prices.

What are the pros and cons of openly disclosing the budget?

- Benefit #1. Technology providers can utilize their expertise to propose cost-saving strategies and innovative scope alternatives, thereby adding more value to the project and making the interviews and product demonstrations more productive.

- Benefit #2. The disclosure of the budget provides a clearer picture of the DOT’s scope and purpose, which ultimately helps prospective technology providers differentiate themselves and tailor their proposals to meet the DOT’s project-specific needs.

- Benefit #3. Providers can detail why their price estimates differ from the DOT’s constrained budget. This process can clarify the project team’s understanding of cost elements, which will aid them in their discussions with their internal budgeting authorities.

- Downside #1. Providers might inflate their prices to meet the budget in scenarios where the DOT has excess funds. However, given that this is a rare occurrence, this risk is mostly theoretical. If the project does have surplus funds, price inflation can occur. But the presence of a single honest provider offering a fair price is enough to keep the competition in check. Providers are unlikely to artificially increase their prices based on the budget; they are more likely to do so based on perceived risks and their need for the project. Further, the procurement process always includes price as a weighted evaluation factor, with additional cost controls and safeguards in place, which also ensures the DOT will not overpay. Therefore, it is typically beneficial to disclose the budget.

In summation, there is little actual risk in disclosing the budget; the risk is mostly perceived. Therefore, the preferred approach is to share the project budget as a strategy to attract the best technology providers at the best prices.

Tip #4: Clearly Establish the Project Team’s Roles and Responsibilities Prior to Scoping

The DOT’s project team should include the perspectives of end users and subject matter experts (SMEs) to ensure the new technology will be a proper fit to accomplish their objectives. However, this does not mean that the end users and SMEs need to be experts in how the technology works or the specific capabilities of a particular technology; rather, these stakeholders should focus on clearly articulating their needs, goals, and current state environment. The biggest needs in a DOT’s project team are usually described by answering the following questions:

- What operational problem is the DOT’s end user group trying to solve?

- What outcomes are the end users and SMEs trying to achieve? What would success look like?

- What are the biggest pain points with the current state? What are the biggest dislikes with how things are done right now?

- What are the most common use cases of how the technology will be used?

- What makes this project unique relative to other DOTs (identifying how the project is unique relative to other DOTs may benefit from benchmarking with other DOTs during market research efforts)? Do the end users have any specific needs that might be overlooked by external technology providers?

In addition, it is typically beneficial for DOT project teams to collaborate with their organization’s IT group to comprehend any technical prerequisites or related policies (e.g., security, functional). These often encompass security considerations, data regulations, and other facets related to integrating new technology into the organization. While the DOT project team is not required to have deep expertise in these areas, they need to engage actively with their IT counterparts to gather this vital information. It is worth noting that the IT department frequently has pre-prepared documentation that can be incorporated into the project’s SOW.

Tip #5: Perform Market Research as Required

All DOT project teams should conduct a thorough process of market research before putting an RFP on the street. Market research refers to the systematic identification of potential technology vendors and products that could fulfill project requirements. This section provides six guidelines to enhance the effectiveness of the market research process.

Market Research Guideline #1: Distinguish Between Market Research and Evaluations

Evaluations are defined as assessments of competing technology providers or products. Such assessments should be kept separate from market research and wait until the formal RFP is launched and full proposals are received. Many project teams start to form preferences and evaluation-like judgments during the market research process, which goes against the principles of a fair, open, and competitive public procurement process.

Instead, project teams should focus on the primary objectives of market research, which are:

- Do not rank technology providers or pass judgment on them.

- Do not solicit proposals, quotes, or product demonstrations from technology providers (all of this is reserved for the later RFP stage).

- Identify all potential technology providers and/or products that could meet the client’s minimum requirements, irrespective of the odds. Evaluative statements during the market research phase should be curtailed, as it is not the appropriate stage for evaluations.

Market Research Guideline #2: Be Cautious of Marketing Information from Technology Providers

During market research, it is crucial not to be swayed by marketing materials and presentations from technology providers. Marketing material could result in an unjustifiable bias among the client’s project team, leading to skewed preferences for certain providers. Market research is not an evaluation process and parallel proposals have not yet been submitted; hence, it is inappropriate to make evaluative judgments at this stage and to review overly marketing-based materials.

Market Research Guideline #3: Discourage Direct, One-On-One Meetings with Technology Providers

While technology providers often request one-on-one meetings with clients ahead of the RFP process under the pretense of better understanding client needs, these meetings can potentially create biased evaluations by building premature relationships. Such meetings primarily serve as marketing opportunities for technology providers and can introduce unnecessary biases within the client teams and evaluators.

Market Research Guideline #4: Exercise Caution When Engaging Vendors Claiming Subject Matter or Industry Expertise

External vendors can provide valuable insight, but they should not be overly relied upon. It is essential to remember that vendors typically rank entire companies and product offerings rather than specific project teams and their capabilities. These vendors may carry their own biases and potentially favor certain technology providers based on previous associations. However, it can be beneficial for vendors to provide a comprehensive list of potential technology providers and systems that could meet the client’s minimum requirements, if this strategy is used effectively.

Market Research Guideline #5: Avoid Traditional RFI Processes Unless Necessary

Traditional request for information (RFI) processes should only be employed if clear objectives have been defined. Many RFIs turn into disorganized collections of marketing content from technology providers with minimal tangible benefits. Before initiating an RFI process, the DOT should identify specific information that needs to be collected and make decisions based on the RFI responses. The DOT should also explicitly tell vendors not to submit marketing materials.

Market Research Guideline #6: Publicize the Project During Market Research

The market research phase presents an opportunity to advertise the upcoming project to the technology provider community, aiming to attract interest and stimulate competition during the RFP stage. This includes identifying points of contact for procurement, indicating an upcoming procurement process, and initiating non-disclosure agreement procedures if necessary to avoid future delays in the procurement process.

Project Team Formation and Key Decisions

Identifying the right team is crucial, and understanding the organization’s level of technological maturity plays a pivotal role in shaping team formation and key decisions. The organization’s internal context ranges from simply upgrading existing operations to the adoption of entirely new technologies without any baseline.

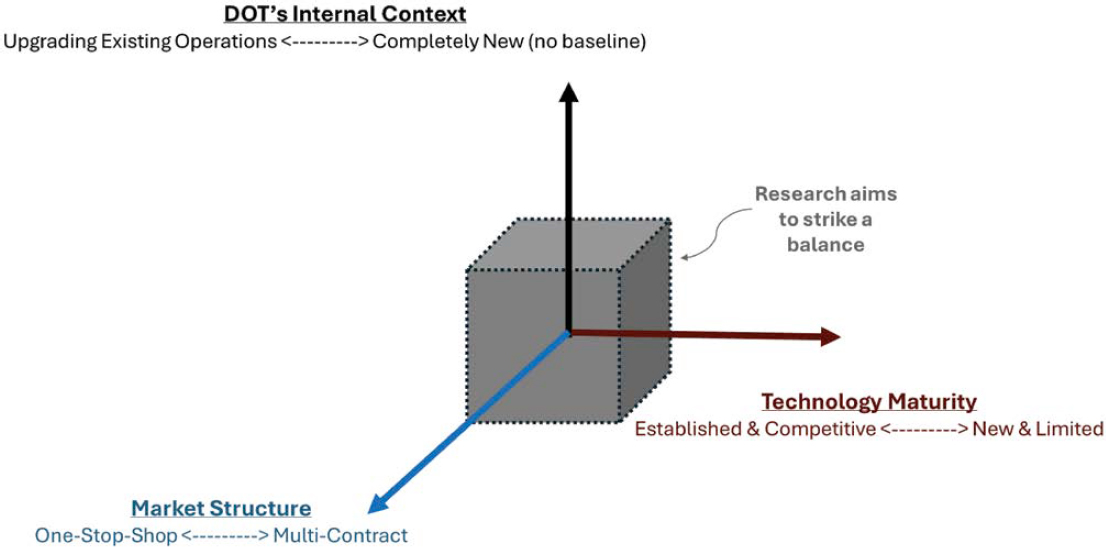

As Figure 9 illustrates, there are three major considerations in the early planning stages of a new technology procurement:

- STA’s internal context. The new technology procurement may range from simply replacing or upgrading an existing legacy system to seeking a completely new technology solution that has no existing use cases of baseline knowledge in the organization. The internal context may also consider the extent to which the new technology will be enterprise-wide or limited to selected internal groups. This consideration is so important because the internal context will impact the level of detail with which the scope and requirements can be gathered (e.g., upgrading an existing technology will have a much more detailed understanding of the current integrations, requirements, and data characteristics).

- Technology maturity. The technology being sought in the procurement process may be a solution that is well-established (e.g., already used by many other DOTs) or it may be a fairly new solution on the market. In the case of a well-established solution, the project team can more easily contact other DOTs as part of a reference-checking process. In more “cutting edge” cases, conversely, the project team may add additional time and resources to market research activities.

- Market structure. Depending on the technology’s complexity, more than a single technology provider may need to be engaged. For example, some technologies are provided by a single provider (the DOT will only sign a single contract at the end of the procurement). In other cases, the technology solution may comprise multiple individual parts, each of which is provided by a separate vendor. In such cases, early decisions need to be made regarding whether the DOT will sign separate contracts or request that all vendors team up in subcontractor relationships.

Overall, this research report attempts to strike a balance between these considerations, understanding that each technology procurement can vary considerably depending on the specific scenario. The research has incorporated feedback from a variety of scenarios. The research aims to find a middle ground that aligns with the complexity and the specific needs of the project. This balance ensures outcomes are both practical and beneficial and avoids extremes that may not be feasible or universally beneficial. Achieving consensus on what constitutes acceptable

advancement in technology is essential. The organization must navigate within its capabilities to develop consistent, useful tools for most technology projects that DOTs will procure.

Market Research Considerations

Conducting market research for a new technology solution prior to entering a formal procurement or solicitation event can be a critical step in ensuring the success of the solicitation process. Market research involves gathering comprehensive information about the available technologies, understanding the needs and preferences of the target users, and evaluating potential suppliers and their capabilities. By analyzing market trends, competitive offerings, and regulatory requirements, DOTs can identify the best-fit solutions and set realistic expectations for performance and cost. Additionally, engaging with industry experts and stakeholders helps identify potential risks and opportunities, ensuring that the procurement strategy is well-informed and aligned with organizational goals. Effective market research enhances decision-making and improves the likelihood of selecting a technology solution that delivers long-term value and meets the organization’s specific needs (by adjusting the subsequent solicitation process).

Another important function of market research is to find and engage potential DBEs. In cases of procuring advanced technology where the DOT may be less familiar with the marketplace as a whole, the need to perform dedicated outreach to advertise, connect, and communicate with DBEs becomes even more critical.

There are several methods of conducting market research. Among the most common are to review existing contract vehicles and approved vendor lists, reach out to peers, conduct internet searches, or query business directories. One formal mechanism that DOTs are familiar with is to initiate an RFI or similar procedure. This method is beneficial in the case of advanced technologies that may be new and therefore have less available information via the aforementioned market research sources. An RFI is a formal document used to gather information from potential technology providers about their products, services, and capabilities. The primary purpose of an RFI is to collect data that help the DOT understand what solutions are available in the market, assess their suitability for meeting the organization’s needs, and identify any potential constraints or opportunities.

An RFI typically includes several sections, such as:

- Project information. An overview of the DOT’s needs and objectives, potentially including a summary of the project scope and technical requirements.

- Response questions. The RFI will typically ask about the technology provider’s offerings, potentially including technical specifications, pricing models, delivery timelines, and support services.

- Market trends. Questions to understand how each technology provider’s offerings compare with current market trends and innovations.

- Additional insights. Some DOTs will ask the technology providers for recommendations, best practices, and any additional information that could be relevant to the DOT’s decision-making process.

RFIs are used early in the procurement process to help organizations refine their requirements, develop a better understanding of the market landscape, and shape the subsequent RFP or request for quotation processes. They are instrumental in making informed decisions and ensuring that the final procurement strategy is comprehensive and aligned with the organization’s goals.

One DOT that participated in the study shared information about their RFI process for a large, enterprise-wide software solution. In this scenario, the DOT conducted an RFI roughly 1.5 to

2 years before issuing the RFP. The RFI was publicly released and was found to be useful in identifying potential providers and gathering budget information (which helped justify the internal budget request), and it aided in defining requirements and evaluation criteria in a manner that was attractive to providers.

In addition to RFIs, most DOTs will also include outreach to other DOTs to understand whether the same technology solution has already been procured and possibly implemented by a peer. DOTs may also examine cooperative purchasing contracts for pre-existing technologies that have already been vetted. An example of this is discussed in Chapter 9 with the case study from Rhode Island.

Cybersecurity Considerations

All new technology procurements must be carefully reviewed from a security standpoint. This represents a significant difference from typical engineering, construction, and operations procurements, which typically do not involve new technologies that present cybersecurity threats.

There must be management support and commitment to establish a strong and responsible cybersecurity culture at the DOT. IT professionals account for roughly 3% to 4% of an engineering organization such as a DOT. Therefore, it can be difficult to establish the importance of IT-related topics, among which cybersecurity may be the most important. An effective strategy to build support and cultural awareness is to discuss new technology procurements in the context of risk to the agency. Another effective approach is to showcase how failure to follow a responsible cybersecurity protocol can slow down the implementation of a new technology, which ultimately expresses the cybersecurity risk in terms of traditional engineering project management, namely, risks to being on time, on budget, and delivering the levels of quality the project was intended to achieve.

From a cybersecurity standpoint, the worst-case scenario occurs if the DOT has already purchased a new technology and then comes to the cybersecurity team afterward to request support in implementation. Rather, the cybersecurity team should be engaged immediately as the project begins early planning.

Most DOTs have matured to the level of preparing an acceptable user policy (AUP) or similar governing protocol. In such policies, typically a prohibited behavior is the solicitation, implementation, or creation of any IT software or hardware solution without following IT-related governing procedures. In other words, if a project team or individual acts outside the policy requirements, there may be justification for personnel action against them. Some DOTs require every employee to sign their AUP (or similar document) every year as part of mandated cybersecurity training.

The nature of cybersecurity is such that DOTs have a wide variety of policies, procedures, and maturity levels. This can lead to instances where technology vendors attempt to play clients off one another; for example, project teams should be prepared for vendor claims such as, “We work with other states, and they don’t ask us to do this.” Such claims are not sufficient justification to omit, overlook, or gain exemption from cybersecurity considerations. The DOT’s cybersecurity experts should always be consulted for their professional assessment.

Another cybersecurity challenge is building the DOT’s security framework along with associated standard policies and procedures. The goal is not to have hundreds of pages of documentation on procedures, but actual living policies and procedures with accompanying administrative controls.

Within individual RFPs for new technologies, there are several cybersecurity documents and procedures that are commonplace:

- The RFP will typically be released with an appendix that prescribes the DOT’s cybersecurity rules and requirements. By submitting a proposal, vendors acknowledge that they accept all requirements.

- The full contract language around cybersecurity is often published in the RFP as well. Although most DOTs do allow for contractual redlines to be submitted by proposing vendors, DOTs rarely budge on terms or conditions related to cybersecurity standards.

- Project teams can also be assured that some flexibility can be accessed concerning cybersecurity. For example, one chief information security officer (CISO) who was interviewed noted that if a new technology does not meet one requirement, but does meet the other 95%, the cybersecurity team and CISO may have the flexibility to modify requirements as necessary. It should be noted that procurement can be a lengthy process, and cybersecurity aspects can change even during the procurement timeline itself (e.g., due to technology advancements, implementation of parallel technology efforts, or changes in databases).

- Some DOTs have project intake processes that consider cybersecurity aspects upon early project ideation. Requested technologies that are expected to reduce cybersecurity threats across the broader agency may be awarded central IT funds in support of the new technology.

Example of Cybersecurity Consideration in Early Project Intake Procedures

MnDOT has a full IT project request process for formally establishing the need for a new technology. The initial request considers the business case for the new technology, which includes aspects such as whether the new technology is commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS), the overall business readiness (with emphasis on how the new technology will impact the existing technology environment, including integrations and data sources), current state environment (existing applications, applicable sunset deadlines, etc.), requirements related to policy or regulation, and initial budgeting (available funds, estimate of internal resources, and total cost of ownership).

All new IT project requests are entered into a centralized planning hub where they are prioritized for funding decisions.

There are also several roles that cybersecurity professionals fulfill during the procurement process itself:

- Cybersecurity professionals often answer questions from vendors and provide explanations during the RFP process.

- Cybersecurity professionals may conduct reviews of proposed technologies or vendors alongside the evaluation process.

- Sometimes cybersecurity professionals serve as formal evaluators during the proposal review process. Other times they are consulted for their input rather than serving as formal voting members of the evaluation committee.

- In many DOTs, cybersecurity evaluations are part of the review in every technology project.

Another important lesson is to recognize that modifications to existing technology are, in effect, the creation of new technology. This applies even if the modification is made under an existing contract. Such modifications should be treated with the same level of scrutiny and consideration as entirely new solutions. Additionally, it is essential to consider these modifications in the context of longer-term implementation and system maintenance. Options for enhancements and upgrades should be evaluated comprehensively to ensure they align with the organization’s evolving needs and security standards. Furthermore, any change made to an application necessitates an update or review of the DOT’s system security plan or equivalent. This is not just a procedural formality; it is a fundamental aspect of maintaining system integrity and security. These practices not only enhance the effectiveness and security of the technology but also streamline the procurement process, ensuring that modifications and new technologies are appropriately evaluated and integrated.

Another consideration is technologies that fall under the “set-it-and-forget-it” category. In other words, technologies that are procured once and may not be revisited for several years (examples include traffic signal devices, programmable logic controls, and supervisory control and data acquisition systems). DOTs should not wait until there is a major problem to revisit these

technologies. Rather, DOTs should plan for reviews at regular interviews. For example, the cybersecurity team may ask internal project teams or departments whether they have recently completed a summary cybersecurity questionnaire.

NCHRP Web-Only Document 355: Cybersecurity Issues and Protection Strategies for State Transportation Agency CEOs: Volume 2, Transportation Cyber Risk Guide is a resource on cybersecurity considerations. This guide touches upon several considerations that are relevant to the procurement of new technologies. Among these considerations are to build an agency-wide culture of awareness and vigilance regarding the importance of cybersecurity, provide staff training related to procurement processes (knowing that most staff are neither procurement professionals nor cybersecurity gurus), and recognize that the gap between agency workforce capabilities and the degree of cybersecurity vulnerability increases each time a new technology is implemented (Ramon et al. 2023).

Finally, one distinction is that cybersecurity is not the same topic as information privacy. Personal and protected information includes sensitive data such as social security numbers, driver’s license numbers, etc. However, this is not typically within the primary jurisdiction of the cybersecurity team and may even be managed by a separate agency altogether (e.g., the Department of Motor Vehicles may oversee the confidentiality of driver licenses). DOTs will typically have established privacy controls that account for instances where confidential information will be involved, even if that confidential information will be managed by another agency.

DBE Considerations

DBE considerations are an important component of the procurement process. When embarking on new procurements, agencies should ensure that DBEs have an equitable opportunity to compete for and participate in DOT-funded projects. This includes establishing DBE goals, encouraging the use of DBE sub-vendors, and providing support through outreach and technical assistance. The DOT’s adherence to DBE regulations promotes a level playing field and aims to foster a diverse and inclusive economic environment within the transportation industry. These considerations are integral to the DOT’s procurement strategy, aligning with broader federal objectives to advance equitable business practices and economic growth among disadvantaged communities.