Practices for Transportation Agency Procurement and Management of Advanced Technologies (2025)

Chapter: 4 Preparing the Solicitation

CHAPTER 4

Preparing the Solicitation

Overview

This chapter addresses the importance of the RFP and describes best practices for structuring the RFP and coordinating the evaluation process.

Solicitation Phase Tools for Practitioners

This chapter also references four tools (provided as appendices) to assist DOTs in the solicitation phase of their technology procurement efforts. They include:

- Appendix H: RFP Contents and Scorecard. A tool that standardizes the evaluation of RFPs by facilitating transparent discussions between customers and procurement teams, thereby ensuring well-defined, clear, and unbiased criteria for vendor selection and aiding in making informed decisions.

- Appendix I: Cost Sheet Example. A detailed template to illustrate how costs can be collected from the vendors.

- Appendix J: Evaluation Guide and Score Sheets. Acts as a playbook for the procurement process, specifying roles, responsibilities, evaluator templates, and ethical guidelines to ensure a standardized, fair, and transparent vendor selection.

- Appendix K: Guide to Effective Vendor Debriefings. A guide that aims to streamline vendor debriefings post-procurement, serving as an effective tool for fostering transparency and encouraging vendor participation in future projects.

Challenges in Writing Effective RFPs

Writing a good RFP is fraught with challenges, one of which is the inherent complexity when multiple award factors are considered. Criteria can range from cost and delivery time to less quantifiable factors such as sustainability practices or innovative capabilities. This not only amplifies the complexity of the RFP but also necessitates a multifaceted evaluation team with expertise across these varying criteria, making the process resource intensive.

Another issue is the extended time frame required for thorough evaluations. An exhaustive analysis of each proposal against complex award factors demands substantial time and resources. Each response needs to be assessed, compared, and ranked, a process that can prolong the overall project timeline significantly.

Additionally, the inclusion of multiple award factors increases the potential for subjectivity in the evaluation process. While some criteria, such as cost and delivery time, are straightforward

and quantifiable, others, such as innovation or sustainability practices, are more subjective and harder to measure consistently. This subjectivity can complicate the evaluation process, making it more difficult to defend decisions and increasing the potential for scrutiny. Furthermore, having more factors can make the debriefing process more challenging, as evaluators must provide clear and detailed explanations for how each factor influenced the final decision, which can be complex when dealing with less quantifiable metrics.

The challenges of writing an effective RFP are especially present for DOTs due to the vast diversity of technologies being procured. Whether it is enterprise software, mobile technology, data analytics, field monitoring systems, or various types of hardware, each comes with a unique set of criteria for evaluation. The complexity of these technologies is also on the rise, with an ever-expanding pool of providers. This technological diversity and complexity make traditional procurement methods obsolete, as they are often not tailored to address the nuances of the technology sector.

Another layer of difficulty is the long-range planning required in transportation projects. DOTs must consider not just immediate requirements, but also future needs that may extend years into the future. This involves life-cycle costing, long-term compatibility, and the capacity for data-sharing across platforms. These long-term considerations can significantly complicate the RFP process, requiring a complex evaluation model that accounts for both immediate and future needs.

Evaluating the cost of technology procurements is a particularly challenging aspect of the RFP process. Costs are often multifaceted and can vary significantly based on a range of factors such as licensing structures, payment terms, and additional fees. For instance, some vendors may offer a straightforward annual licensing fee, while others might employ a more complex, tiered pricing model based on the number of users or usage levels. Additionally, the upfront costs of installation and implementation can differ widely and may not be fully transparent in the initial proposals. Long-term expenses, such as ongoing maintenance or potential upgrades, further complicate the cost assessment. Therefore, comparing costs across various proposals is rarely a straightforward exercise and often necessitates a deep dive into the financial intricacies of each option to arrive at a truly cost-effective decision.

In the transportation sector, procurement is often a highly collaborative process involving multiple stakeholders. Sometimes, DOTs are the primary end users and must collaborate with other units such as procurement and IT departments. In other instances, they serve as SMEs, offering advice and insights to other business units during the acquisition process. This variability in roles adds another layer of complexity to the RFP writing and evaluation process, as the criteria and evaluation models may differ depending on the stakeholders involved.

Structuring the RFP

A well-organized RFP is crucial for a smooth and efficient procurement process. Organized formatting and clear instructions make it easier for vendors to determine what exactly needs to be submitted, thereby minimizing the risk of disqualification due to incomplete or incorrect submissions. An organized RFP also exudes professionalism, fostering confidence in the process and the issuing organization. Moreover, a structured format is simpler and faster for vendors to review, which in turn encourages more and better-quality responses. A well-organized RFP reduces frustrations for all parties involved, streamlining the process and increasing the likelihood of a successful procurement outcome.

It is preferred that a technology RFP for DOTs be organized into the following seven parts:

- SOW,

- Current conditions,

- Proposal requirements,

- Evaluation procedures,

- Administrative requirements,

- Proposal forms, and

- Attachments and exhibits.

Part 1: Create a Clear SOW

The SOW serves as a critical component in the procurement preparation phase, particularly for DOTs. It outlines what the DOT aims to acquire from technology vendors and may go by various names, such as SOW, specifications, or minimum qualifications. The SOW provides essential information that vendors require to formulate competitive and accurate proposals. It directly impacts the number and quality of proposals received.

A poorly prepared SOW can have several detrimental consequences. Lack of clarity or unrealistic expectations can lead to decreased competition, as vendors may opt not to participate in the bidding process. Those who do participate may offer less accurate pricing, leading to a wide array of cost estimates that can cause confusion during the evaluation stage. Additionally, vague or incomplete SOWs often result in proposals filled with marketing “fluff,” as vendors resort to generic or boilerplate materials in the absence of specific project information. This not only hampers the selection of a well-matched team but also increases the likelihood of change orders and unexpected challenges during technology implementation. Chapter 3 of this report provides significant detail on how to structure the SOW.

Part 2: Current Conditions

Similar in purpose to the SOW, the current conditions serve as a foundational baseline that allows vendors to fully comprehend the scope and implications of a project and thereby develop a realistic proposal. This section generally starts with an overview and background section to give a snapshot of the existing situation. Measurable aspects like volumes and quantities are outlined to offer scale and perspective. Pain points specify the problems or challenges currently faced, while strengths highlight areas of efficiency or effectiveness. Supplementary figures, diagrams, and references add depth and detail to aid understanding. This section is crucial for vendors for multiple reasons: it helps them gauge the impact of the proposed changes, confirms whether the SOW is practically achievable, allows the identification and preemptive addressing of potential challenges, and provides a means to verify the accuracy of the SOW. By laying out the current conditions comprehensively, vendors can make more informed decisions and offer proposals that are both realistic and targeted to an organization’s specific needs.

In the context of procuring technology, the section on current conditions could include several specific elements. One important aspect is an overview of existing systems, such as software, databases, and hardware setups. This gives vendors a fundamental understanding of the technology landscape they would be entering. Another important point to include is a high-level description of how these various systems interact with each other, which helps to outline possible integration points or challenges. If the systems or technology are user-facing, details about public experiences, such as customer interfaces, are useful for gauging requirements for usability. It is also helpful to include details about the types and volume of data the organization manages, as this can have implications for data storage, processing, and security. Providing these specifics ensures that vendors can make more tailored and context-aware proposals.

Part 3: Proposal Requirements

The proposal requirements should be straightforward and concise, outlining exactly what information and content are needed for evaluation. Vendors should be directed to corresponding proposal forms that capture all the required data and insights. To keep submissions manageable and focused, maximum page limits should be defined. By setting clear guidelines and parameters, vendors can provide the specific information needed for a thorough evaluation, which will streamline the review process for both parties.

General Formatting Requirements

At first glance, document formatting might appear inconsequential; however, it plays a pivotal role in how smoothly the evaluation process can be conducted. Guidelines for formatting should be crystal-clear to prevent any ambiguity. For example, providing explicit details on how to submit the proposal documents is important:

- Submit the proposals on standard 8½″ × 11″ document size.

- 1″ margins.

- Minimum font size of 10.

- Font type must be Times, Arial, or Calibri.

- Must be single-spaced.

- Definition of a single page (if using maximum page limits).

- Specify the use of required forms and templates.

This is just an example, as each RFP template and DOT will have its own requirements.

Submission Requirements and Procedures

The most common method for proposal submission is electronic. Therefore, details such as the website or link for submission and any limitations on file type and sizes should be explicitly stated. Additionally, it is preferred that the cost details of proposals be submitted in a separate envelope or document, which is not provided to the evaluators until the evaluation process is completed. This step minimizes the risk of bias during evaluation. The research team has found that providing the proposers’ cost details to evaluators while they are reviewing other aspects of the proposal can greatly affect their evaluations. For example, a remarkably low-cost proposal might result in an evaluator predisposed to view that vendor’s entire submission more favorably (if they perceive it to be a “good deal”) whereas another evaluator may question the viability of a low-cost proposal (if they perceive it to be “too good to be true”).

Proposal Contents and Due Diligence

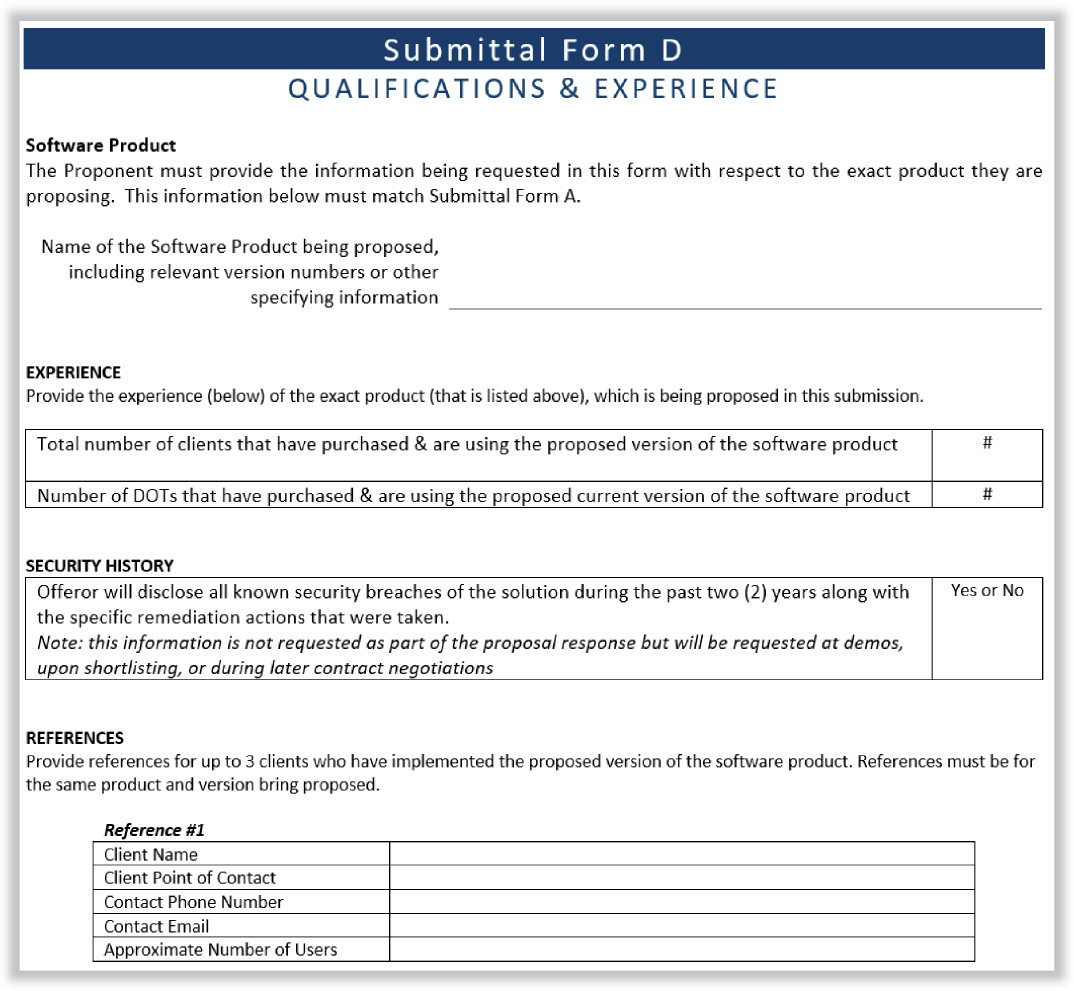

The RFP should meticulously outline what exactly needs to be included in the proposal. For instance, if the issuing organization wishes to gauge qualifications and experience, instructions should dictate that proposers include specific, clear data on their backgrounds (see Figure 10).

Publishing the evaluation criteria and their respective weights is an advisable approach. It allows vendors to concentrate on what is most critical to the decision-making process of the client, reducing the likelihood of objections. If the criteria and weights are not specified, vendors may perceive the selection process as opaque and may suspect that weights were manipulated after proposal review to achieve a certain outcome.

Regarding cost, this should be determined through numerical analysis. The vendor who submits the lowest-cost proposal receives full points for the cost criterion. Other vendors earn points proportional to how much higher their cost proposals are in relation to the lowest cost.

In the transportation technology space, there is a growing presence of new tech startups, making due diligence crucial. With approximately 40% of businesses in the IT sector closing within 3 years, this typical life cycle is a crucial consideration. Identifying a superior vendor and solution is advantageous, but their potential to exit the market within several years could create significant long-term serviceability issues. Factors to scrutinize within a vendor’s profile might include:

- The entities or individuals financially backing the company.

- A proven track record over the last 5 years of successful project completions, supported by customer testimonials (however, DOTs should be careful not to make such experience requirements overly burdensome, which can then limit new entrants).

- Tangible evidence suggesting the vendor’s sustainability and longevity in the industry.

- Previous experience in handling similar projects.

- The origins of the company, as well as the professional background of key project members.

Another consideration for DOTs is that there may be a mismatch between the typical lifespan of IT vendors and highway transportation systems. Advanced technologies may be provided by newer vendors who have been in business for a relatively short period when

compared to the decades-long operation of highway transportation systems. Even vendors who have been in business a long time may not provide long-term commitments to update and service products or provide replacement components. For example, the technology vendors interviewed in Chapter 6 noted that their preferred contract lengths were between 3 and 5 years long.

Part 4: Evaluation Procedures

The evaluation procedures section of an RFP outlines the methodology for assessing proposals against predefined criteria. It specifies the weighting for each criterion, ranging from cost and technical capabilities to more qualitative aspects like innovation or sustainability. The section also details how scores will be assigned and aggregated. Additionally, the role of the evaluation committee is delineated, including responsibilities for reviewing, scoring, and ranking the proposals. This section is crucial for transparency and fairness, as it sets the framework for an objective evaluation, allowing vendors to understand how their submissions will be evaluated. See Chapter 4 for more details. It is important to remember the “Golden Rule” of evaluation procedures.

The Golden Rule of Evaluation Procedures:

Clearly state exactly how proposals are going to be evaluated and scored . . .

. . . And then follow through on what was said.

It is also important to understand that there are “weighted” and “non-weighted” metrics. Weighted metrics help in computing the most advantageous proposal by assigning points, whereas non-weighted ones ensure that the bidder meets basic requirements. Weight metrics consist of two elements: (1) facets scrutinized and scored by the appraisal committee and (2) numerical comparisons based on information given by vendors.

Understanding that weighted criteria, such as a vendor’s written proposal, are designed to help the DOT confirm the vendor’s previous experience and grasp of the project’s requirements is crucial. This confirmation can be derived from information about the vendor team’s prior work, completed projects, or individual resumes. Evaluating the vendor’s proposed methodology, solutions, and timelines is an effective way to gauge their capacity to meet the project’s goals.

Additionally, it is essential to address the issue of vendor capture, especially with bespoke systems. Vendor capture occurs when an agency becomes dependent on a single vendor, especially with custom systems. To mitigate this, incorporating requirements for thorough documentation and comprehensive staff training can help ensure the agency can manage the system independently, thereby reducing reliance on the vendor. This approach also promotes internal technological expertise among the agency’s own staff.

There are many examples of potential evaluation criteria, such as:

- Schedule/duration,

- Past experience,

- Staff resumes,

- Methodology and approach,

- Service approach,

- Minority and Women-Owned Business Enterprise requirements,

- Technical requirements,

- Financial capabilities,

- Subcontractor plan,

- Quality control plan,

- Staffing plan,

- Safety plan,

- Technology experience,

- Bonding and insurance,

- Warranties, and

- Claims and litigation history.

Regardless of the criteria used in an RFP, it is crucial to include elements that allow for differentiation among proposers. Extensive evaluation criteria have several downsides. For one, they can increase the amount of time and effort required from proposers, which may discourage participation and result in a lower response rate. On the evaluation side, more complex proposals require a longer assessment period, which lengthens the overall procurement process. Importantly, a more involved or complex RFP does not necessarily lead to the selection of the “best” proposer for the project. Therefore, it is essential to strike a balance to ensure the RFP effectively distinguishes between candidates without unnecessarily complicating the process for all parties involved.

CPE supports an approach where no single criteria should account for more than 35% of the total points in the evaluation process. Placing too much emphasis on one particular item can skew the assessment and may not reflect the overall suitability of a proposal. By capping the weight of any individual criteria, a more balanced and holistic evaluation approach is achieved, allowing for a fair and comprehensive assessment of all proposals.

Individual Evaluations

It is preferred that evaluations be conducted on an individual basis prior to a panel or consensus meeting (wherein evaluators may reconsider their evaluations based on panel discussions). This approach fosters independent thinking and minimizes the risk of collective bias affecting the outcome. Evaluators should be advised not to discuss their assessments with anyone before allowed outlets (such as panel meetings) and should only contact the procurement team if they require clarification on any aspect of the evaluation process. This approach also ensures that procurement has a record of individual scores that can be referred to in case of any subsequent changes after discussion (to ensure fair treatment and proper procurement justification is documented).

It is imperative that evaluations remain as unbiased as possible. To achieve this, evaluators should rely on logic and verifiable performance documentation when determining their ratings. The aim is to be as honest and fair as possible in assigning these ratings. It is important to note that these evaluations are not used for awarding a specific project, but rather for pre-qualifying vendors for inclusion in an overall program. These “pre-evaluations” help the owner feel more confident that the vendor may meet their needs. Also, the procurement official should feel free to seek clarification on any ratings submitted. This may include requesting additional comments from evaluators or making the decision to modify or reject a rating entirely.

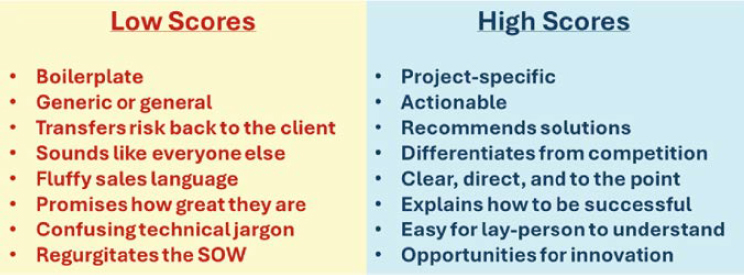

When evaluators are being educated on how to score a proposal, Figure 11 may help them determine what constitutes a “low” score versus a “high” score.

Interviews

For large or complex projects, meeting the individuals who will be assigned to the contract can be beneficial. This can be accomplished through a team presentation. The first consideration in this approach is the length of the presentation. Most presentations typically last between 60 and 90 minutes. While DOTs are allowed to conduct longer sessions, exceeding a 2-hour duration could make it difficult for evaluators to maintain focus on the content.

To better ascertain the total time commitment for the agency to conduct interviews, a typical example may be useful. Assuming four short-listed technology providers are each invited to a 2-hour interview process, it is likely that the agency will need to spread the four interviews across two workdays. With an evaluation committee of five members, this is more than 40 hours of collective personnel time to participate in interviews—and this does not include the participation of one to two procurement representatives (another 8 to 16 hours) nor the surrounding coordination and logistics of the interviews (which can be another 5 to 10 hours of effort). In sum, an interview process can require more than 50-60 hours of total personnel time for an agency to conduct. Therefore, interviews are often reserved for larger and more complex projects and must also be balanced with the potential need to conduct technology demonstrations, which require a similar number of resources as interviews.

It is advisable to prepare the agenda script before releasing the RFP, and this script should be included in the RFP document itself. Suppliers usually prepare a PowerPoint presentation to cover the required agenda topics and may supplement this with additional handouts or illustrations. Though such presentations were traditionally conducted in person, a recent trend has been a shift toward virtual presentations. After the supplier concludes the presentation, it is then scored by the evaluators.

Instead of team presentations, individual interviews are a more effective method for assessing the qualifications of personnel for large or complex projects. Conducting these interviews separately allows the project owner to evaluate the true expertise and capabilities of each team member. Conducting individual interviews can help:

- Identify whether the individual has experience and expertise.

- Identify whether the individual has thought about the specific project.

- Identify whether the individual can lead the team.

It is crucial to meet the individuals responsible for the day-to-day execution of the project or service and determine whether they are “experts” in the field. Interviews should generally involve the overall project manager or project lead, as well as one to two other key personnel who will significantly contribute to the project’s success. For technology-related projects, the project lead and the integration lead should typically be interviewed.

While it is important to interview critical personnel, it is also necessary to be mindful of their time constraints, as these individuals are often in high demand. To minimize strain on the supplier, the process should be straightforward. Interviews should be scheduled with ample advance notice and clear expectations should be outlined in the RFP. A viable time frame for each interview is 20–25 minutes.

The research team has noted that individuals regarded as experts commonly display the following traits during interviews:

- Answer questions quickly and concisely.

- Present the service as straightforward and uncomplicated.

- Aim to take control to lessen the DOT’s workload.

- Proactively identify potential risks and challenges, along with mitigation strategies.

- Willingly accept both responsibility and accountability for tasks and outcomes.

The following are some suggested interview questions:

- Describe what differentiates you personally from your competition.

- Describe your project approach to completing the scope within our time and budgetary constraints.

- What are the greatest risks or challenges with completing this work?

- Describe how you will integrate our existing data into the new system and your plans to quality control (QC) the data to identify issues/mistakes.

- How would you verify that data are stored pursuant to our organization’s security requirements?

Other project-specific questions can also be valuable.

Key Points for Evaluation Procedures

In summary, during the evaluation process:

- Transparency is enhanced by openly disclosing both criteria and their corresponding weights.

- Although a variety of criteria can be utilized, adding more does not necessarily improve the quality of submissions and may increase work for both vendors and evaluators.

- The focus of evaluated criteria should be on effectively distinguishing between different proposers.

- While written responses in proposals often address both past experience and current needs, the latter should be given priority.

- As a general guideline, the cost factor should be weighted at approximately 25% and should never exceed 35% of the overall evaluation.

- For large or complex projects, individual interviews are more effective than team presentations for assessing team member qualifications. Interviews should involve key personnel, be straightforward, and last 20-25 minutes to evaluate the expertise and fit for the project.

Part 5: Administrative Requirements

The administrative requirements section of an RFP serves as a guidepost for all logistical and procedural aspects related to the submission and evaluation of proposals. It typically includes crucial deadlines, such as when proposals are due and the timeframes during which interviews or presentations may occur. Insurance requirements, detailing the types and levels of coverage expected from vendors, are also often specified. Other administrative items that can be outlined here range from the format in which proposals should be submitted to how queries about the RFP should be directed. This section ensures that vendors are fully aware of the administrative expectations and timelines, thereby streamlining the overall procurement process.

Part 6: Proposal Forms

The inclusion of proposal forms for every component of a vendor’s submission is a best practice that benefits both parties involved in the RFP process. By providing specific forms or templates for each requirement or section of the proposal, vendors are guided on precisely what

information is needed. This not only simplifies the task for vendors but also ensures uniformity in the responses, making it easier for the evaluation committee to compare and assess submissions. Failure to use such standardized forms can lead to disorganized proposals that are time-consuming to evaluate and can introduce inconsistencies in the review process. To be clear, it is preferred that every component that will be submitted and/or evaluated should be done as a fillable form or template.

In many of the technology RFPs that were analyzed from DOTs as part of the literature review, the RFPs successfully defined the structure of vendor proposals that were desired; however, oftentimes no corresponding forms or templates were provided.

Cost Proposal Forms

Evaluating the cost of technology procurements poses a unique set of challenges, especially for DOTs. Understanding the major factors that drive costs is crucial; these can range from the types of licenses required and the level of employee involvement to the number of transactions and storage needs. Vendors may employ a variety of pricing models, further complicating the comparison process and making it challenging to determine the true value of each proposal.

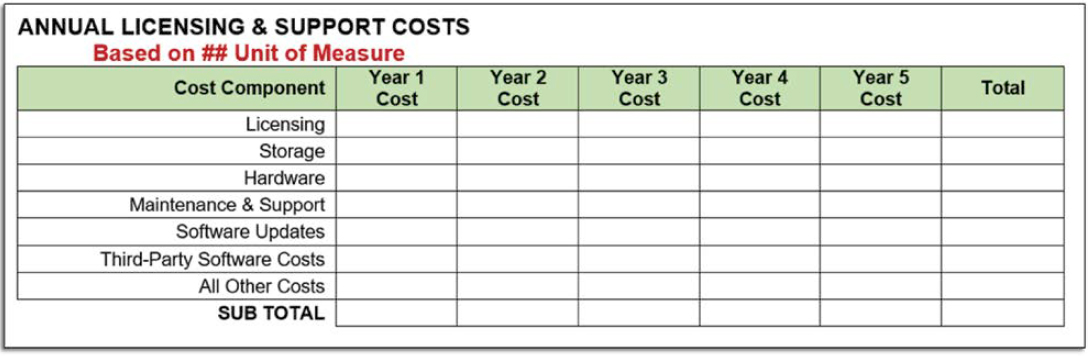

To mitigate these challenges, adopting a standardized form of assessment is advisable. This approach not only facilitates uniform evaluation but also allows for a comprehensive understanding of the costs involved. The form should consider both one-time expenditures like implementation and setup, as well as recurring costs such as licensing and ongoing support. This comprehensive method enables a more accurate and fair assessment of the total investment required for each technology proposal. Figure 12 shows a simple example of different types of annual cost components, including licensing, storage, hardware, maintenance, and updates. If a DOT is not sure how to evaluate cost, the best approach is to use simple definitions.

Part 7: Attachments and Exhibits

Attachments and exhibits are included in a supplementary section in an RFP, housing technical project details, feasibility studies, drawings, plans, specifications, and any other intricate information relevant to the project. By segregating this complex and detailed information from the main body of the RFP, the core document remains streamlined and easier to comprehend. This approach is conducive to attracting a broader range of vendors, as they can quickly grasp the essentials of the RFP while still having access to in-depth information needed for a comprehensive proposal. This organization enhances both the readability and the effectiveness of the RFP as a tool for procurement.

Create a Source Selection Plan Before RFP Release

The source selection plan (SSP) outlines the methods for assessing and rating submitted proposals and should closely correspond with Parts 3 and 4 of the suggested RFP format. Serving as a guide or set of instructions for evaluators, the SSP describes how the evaluation and scoring of proposals will be conducted, effectively acting as the “rule book” for the process. This document may also be referred to as the “evaluation guide,” “source selection guide,” or “proposal evaluation guide.” The SSP should cover the following elements:

- Duties and obligations of the procurement team/buyer.

- Ethical considerations and conflict of interest protocols.

- Methods for evaluation and scoring guidelines.

- Additional key factors.

Finalizing the SSP—that is, the evaluation process—is crucial prior to issuing the RFP. This ensures that evaluators and domain experts can contribute their insights before the RFP is made public. Ultimately, the SSP provides an agreement between the program office and the acquisition office as well as instructions for evaluators. Appendix C includes an SSP template.

Duties and Obligations of the Procurement Team/Buyer

Different individuals involved in the procurement serve varying functions. This section will describe these roles.

Procurement agent (also known as contracting officer, purchasing specialist, buyer, etc.)

- Represents the procurement office.

- Ensures all parties adhere to relevant policies, regulations, and rules throughout the procurement cycle.

- Assumes responsibility for all matters involving the procurement, from initiation to completion.

- Provides guidance and assistance to evaluators, helping them navigate the complexities of assessment.

- Schedules critical activities to streamline the procurement operation.

Evaluators

- Assess and rate submitted proposals.

- Uphold impartial and equitable decision-making.

- Limit bias or external influence.

- Avoid any conflicts of interest.

Ethical Considerations and Conflict of Interest Protocols

The SSP is not a resource for ethical or statutory advice. However, if a member of the evaluation committee has concerns about potential conflicts of interest or ethical dilemmas, they should immediately notify the procurement contact. The buyer provides conflict of interest and confidentiality statements to all evaluators and collects signed forms for the official procurement file. Should an ethical conflict arise during the evaluation process, the buyer is responsible for safeguarding the fairness of the process and minimizing potential harm through legal or public repercussions.

Methods for Evaluation and Scoring Guidelines

The SSP will describe how the evaluation process is to take place. In general, there are four major steps to the evaluation process:

- The procurement contact will send the responsive proposals to each evaluator.

- Each evaluator will review and score each document. Evaluators should take notes to highlight any major strengths or weaknesses.

- Evaluators will participate in a consensus meeting to discuss their thoughts on each proposal.

- The procurement contact will identify the final ratings of each proposal.

This section of the SSP will also outline the methods evaluators should use to score proposals, including the rating scale and the importance of conducting individual assessments. It will guide evaluators on how to provide insightful comments (these comments will also be helpful during debriefings; see Appendix K for a vendor debriefing template).

RFP Administrative Best Practices

After creating an effective RFP, attention shifts to assessing the incoming proposals. The criteria for this evaluation should be outlined in the RFP. This section delves into how to execute a fair and streamlined appraisal procedure. One important reminder is to use fewer criteria wherein the number of written responses required of vendors does not become overly burdensome. In some instances, client organizations may request a written response for every individual requirement that is itemized in the SOW; however, this adds substantial paperwork, which is time-consuming and may be a deterrent for top-tier software firms. Should the owner collect documents from vendors outlining how their offering meets the SOW, avoid giving it excessive importance. Let software demonstrations serve as the avenue for checking actual product capabilities.

Advertising Period

The advertisement period during the RFP phase is a crucial window that spans from the time the RFP is issued until the deadline for proposal submissions. This is the period during which suppliers prepare their proposal responses. Key activities that take place during this time include issuing the RFP, holding a pre-proposal meeting, and releasing any addenda. The length of the advertisement period can vary depending on the complexity of the project and the requirements for the proposal. For small or simple projects that do not require subcontractors and have straightforward proposal responses, a 4- to 6-week period is generally sufficient. However, for larger or more complex projects that require the involvement of subcontractors and demand more intricate proposal responses, an advertisement period of 6–8 weeks is advisable.

Pre-Proposal Meetings

Pre-proposal meetings serve as a vital component in the procurement process, aiming to educate and inform potential vendors about the project’s scope and objectives. These meetings typically have a structured agenda where the client provides a high-level summary of the SOW, and the procurement agent reviews procedural requirements. It also offers an opportunity for suppliers to ask questions. While some organizations make attendance at these meetings mandatory to ensure vendors receive critical information, others opt for a more flexible approach, recognizing that unforeseen circumstances can prevent attendance. If crucial details not present in the RFP are discussed, they should be disseminated via an addendum.

Logistical considerations for these meetings are equally essential. When the meeting is conducted in person, the room should be adequately equipped with sufficient seating for both vendors and internal attendees, and presentation tools such as projectors and computers should be readily available. Virtual meetings require proper software licenses for anticipated attendance and should undergo a test run to avoid technical difficulties. Regardless of the meeting format, a sign-in sheet is necessary for tracking attendance, especially if the meeting is mandatory, and can facilitate networking among vendors.

Lastly, the meeting should be interactive to provide maximum value to attendees. The question- and-answer segment is essential for clarification and allows vendors to resolve minor questions instantly, while major queries that deviate from the RFP should be submitted in writing for formal responses. The conclusion of the meeting should reiterate important timelines and remind vendors to submit all questions in writing. Site walks can also be included for projects where understanding the physical space is crucial. The aim is to treat this meeting not as a mere procedural step, but as a chance to help vendors submit more informed and competitive proposals.

Evaluation Procedures

The evaluation process for proposals in a project involves a multi-step approach for robust and fair selection. An evaluation committee, ideally consisting of three to seven members with a mix of technical and non-technical skills, is crucial. The process begins with an administrative review that weeds out non-compliant proposals based on set criteria such as timely submission and formatting. It is advisable to include checklist templates in the RFP for clarity and efficiency. These proposals then go through a rigorous scoring matrix, often built in Excel for its simplicity and functionality, to evaluate various criteria such as cost, qualifications, and approach. Analyses of the results encompass not only calculations but also risk minimization strategies such as dual spreadsheet comparisons and checks for evaluator errors. Formatting of the spreadsheet for readability and a thorough cost analysis are key to quality results. The end goal is to transition to negotiations with the highest-rated proposer.

Creating the Evaluation Committee

Optimally, an evaluation committee should have between three and seven members. Fewer than three makes justifying scores challenging, while more than seven complicates coordination. The team should combine both technical and non-technical evaluators. In this context, technical evaluators are defined as staff who have experience and knowledge of the new technology and how it will operate (at least to some level of detail). Often technical evaluators are considered among the internal SMEs (who have knowledge of the project and technology being procured). Non-technical evaluators, conversely, are typically regarded as non-SMEs. Sometimes non-SMEs are required to “fill out” the evaluation committee because the DOT may not have enough SMEs to comprise an entire committee. Non-technical evaluators can also provide the viewpoint of end users or adjacent users who may occasionally interact with the future technology (yet may lack detailed knowledge of its use, maintenance, integrations, and so forth).

The Evaluation Period

The advertisement period marks the end of the RFP stage and initiates the selection phase, where all compliant proposals are assessed. The evaluation process begins with an administrative review, conducted by the procurement agent, to determine whether each proposal is “responsive.” Proposals are scored on a pass/fail basis and must meet specific criteria, such as timely submission and adherence to all proposal requirements such as paper size, font, and language. Firms that fail this initial screening are immediately eliminated from further consideration and will not be assessed by the evaluation committee.

Following the administrative check, the focus shifts to the “responsible” aspect, assessing vendors’ capabilities and qualifications to meet the project’s demands. This includes verifying certifications, financial strength, insurance, and other requirements. To streamline this process, checklist templates for all responsiveness and responsibility requirements should be included in the RFP. This aids vendors in confirming their compliance with all criteria and assists procurement agents in efficiently reviewing the submitted proposals.

Once proposals pass these initial screenings, they are then scrutinized by an evaluation committee, typically comprising three to seven personnel who have some connection to the project. This committee evaluates and scores the written proposal responses based on predetermined criteria and weights. This evaluation may also involve a consensus meeting, presentations, and interviews, particularly for large and complex projects. Non-scored elements in the technical evaluation, such as cost, might still influence the overall ranking; for example, the contract officer rather than a technical review panel may be responsible for tracking cost evaluations.

The final stages of the selection phase may involve best and final offers for more complex projects to ensure proposals are comparable. Once evaluations are complete, the process transitions to the negotiation stage with the highest-rated proposal. This comprehensive multi-step approach ensures a thorough and fair evaluation, aiding in the selection of the most qualified vendor for the project.

Creating a Scoring Matrix

The purpose of creating a scoring matrix is to systematically analyze all submitted proposals consistently and efficiently. Microsoft Excel serves as an excellent tool for this task because it is simple to use and widely accessible. Additionally, the matrix does not require complex formulas and can be set up even by someone without an Excel background. The primary activities involve preparing an Excel matrix to prioritize information based on defined criteria such as approach, qualifications, interviews, and cost.

In setting up the Excel file, it is crucial to understand its basic elements such as rows, columns, and cells, as well as worksheet tabs. For each criterion, a new worksheet should be inserted and renamed accordingly. The setup includes entering firm names, evaluator names, and other relevant data. While data for most criteria can be easily copied across sheets, the cost data usually require a different treatment. Unlike other criteria, where a higher number is preferable, a lower cost is generally considered better. Therefore, cost sheet setup will differ from other sheets.

The analysis phase comes after the setup, where each evaluator’s scores are entered and calculated. To identify the best score among all, an “analysis” tab is added for a quick overview. The calculations are not too complicated but require patience and care to ensure accuracy. If you are not comfortable with Excel formulas, it is perfectly fine to manually enter the numbers. It is crucial to spot-check all results to minimize errors. To conduct a quick analysis or comparison, formulas can be used to compare the scores of the first- and second-place vendors, as well as the first-place and lowest-cost vendors.

In summary, Excel offers an effective yet straightforward way to manage and analyze large amounts of data for proposal evaluations. Although formulas are simple, caution must be exercised to avoid errors, especially when you are dealing with multiple evaluators, proposers, and criteria. Always take your time and double-check your work. Excel’s flexibility also allows for running multiple matrices, which is particularly useful when shortlisting candidates or dealing with complex projects.

Analyzing the Results

Analyzing the results of a proposal evaluation involves more than just collecting and calculating data. Ensuring the quality of your results is crucial for informed decision-making. This guide aims to provide a comprehensive approach to minimizing risks, recognizing evaluator mistakes, understanding the importance of formatting, and conducting thorough cost analysis.

Best Practice 1: Focus on Minimizing Risk.

To ensure the integrity of the evaluation, consider these options:

- Create two versions of the spreadsheet and compare results. If both versions yield the same output, your risk of errors is reduced.

- Request that another person create their own spreadsheet for comparison. Independent verification can add another layer of certainty to your findings.

Best Practice 2: Recognize that Evaluators Make Mistakes.

Be vigilant in checking evaluator scores for inconsistencies or errors. Discrepancies could indicate a lack of understanding of the criteria or simple human error, which can skew the outcome.

Best Practice 3: Formatting Can Improve Efficiency.

Inefficient or unclear formatting can make your spreadsheets difficult to understand. Keep these tips in mind:

- Group data into major categories: cost, fees, hourly rates, lump sums, etc.

- Use symbols and shapes along with colors to highlight strengths and weaknesses. This can help users understand which areas require attention immediately.

Best Practice 4: Conduct a Thorough Cost Analysis.

Understanding the financial implications is crucial. Basic cost metrics you should consider include:

- Minimum (min.),

- Maximum (max.),

- Average (avg.),

- Outliers or any cost risks, and

- Significant differences/disparities in projected hours between proposals.

Best Practice 5: Calculate Comparisons and Create Different Evaluation Simulations.

Often, comparisons between the highest-ranked supplier and the lowest-priced supplier are necessary for evaluating the effectiveness of the RFP process and the value provided to clients. Running various evaluation model simulations can offer a comprehensive view. Initially, the way different evaluators score the same supplier should be examined to detect inconsistencies or subjective biases. Next, exploring the scoring dynamics between the top two suppliers reveals what specific factors contribute to the differences in their rankings—whether it is quality, speed, innovation, or something else.

Close examination of how tight the top two to three scores are can shed light on whether multiple suppliers are similarly qualified, thus necessitating a more nuanced evaluation based on secondary criteria. An analysis of the impact of cost helps clarify whether a low or high price equates to the best quality. Finally, a study of how individual evaluators’ scores influence the overall rankings can show if certain evaluators are skewing the results and may suggest a need to revisit evaluation guidelines.

Through these varied simulations, hidden biases may be discovered, areas for RFP process improvement may be identified, and, ultimately, a more well-informed decision that maximizes value to the DOT can be reached.

Consensus Meetings

A consensus meeting serves as a pivotal point in the RFP process, aiming to align the evaluators’ perspectives for informed decision-making. To achieve this goal, it is essential to be well-organized and follow a structured approach.

It is important to confirm that each evaluator has submitted not just the ratings but also their comments. If there are missing elements, contact the evaluators to obtain this information. A quick assessment of each evaluator’s score should also be carried out to ensure that it aligns with their comments. Conducting these activities in advance will minimize delays during the meeting itself.

Setting up the Meeting

The meeting should ideally be planned well in advance, with a date set as part of the source selection plan. Although a reminder sent to the evaluators 2 weeks before the meeting is advisable, there should be no last-minute scrambling to schedule the event. While most consensus meetings can be conducted within 2-4 hours, it is prudent to set aside an entire day to accommodate any unforeseen delays or discussions. Room requirements include adequate space and necessary equipment such as a computer and projector.

Running the Meeting

The meeting should start by walking through the agenda, which can be segmented based on variations in scores. This approach ensures that differing viewpoints are discussed first, followed by areas where there is greater consensus. It is crucial to reassure evaluators that the objective is not to pressure anyone into changing their scores. The meeting should serve as a platform for evaluators to openly discuss each proposal, ensuring that no crucial information has been overlooked.

The meeting also serves to fortify records for any future debriefing sessions or, in worst-case scenarios, formal protests. Therefore, it is essential to maintain detailed records of the evaluators’ reasoning and documentation. If during the meeting, something does not feel right, stop the discussion and schedule an escalation event with a supervisor.

Final Steps

At the end of the meeting, evaluators should be shown an adjusted average score and reminded of the rating scale. If necessary, a final consensus score should be obtained from all evaluators. In some cases, secondary meetings may be required for product demonstrations or presentations.

Keep in mind that the main objective of a consensus meeting should be an open discussion rather than coercion of score adjustments. Meetings often last 2-4 hours, but it is advisable to plan for a full day. Sound pre-meeting preparations can help make the process smooth and efficient, ensuring that no crucial details are missed. It is also important to have justification and documentation when scoring results change during a consensus meeting.

Technology Demonstrations

Many vendors have specialized demonstration experts whose primary role is to showcase their product in the most favorable light during the sales cycle. To ensure an objective evaluation, DOTs should take steps to exclude these experts from the product demonstration stage. Instead, treat these demonstrations as product verifications, not as traditional demos. Proper planning for this verification process should be finalized before issuing the RFP, and vendors should be given written guidelines as part of the initial RFP documentation.

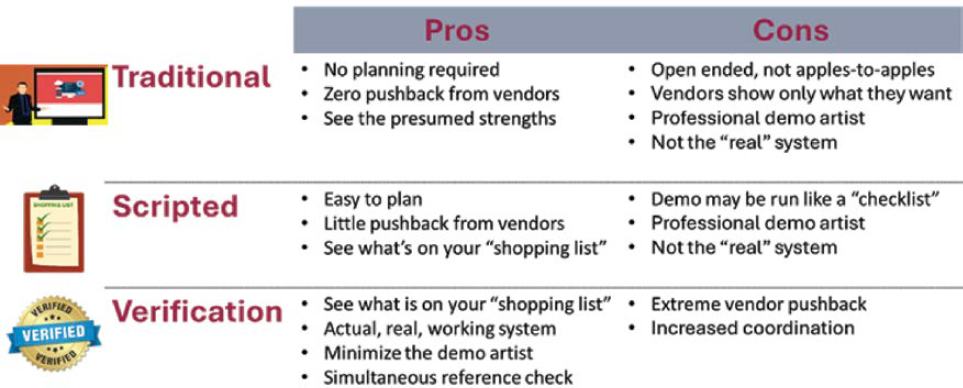

There are three types of software demonstrations:

- Traditional. The traditional software demonstration is essentially an open forum where vendors have the freedom to showcase their products. This type of demo requires the least amount of planning from the client’s side and is often the easiest to set up. A notable feature of traditional demonstrations is that they are generally conducted by a “professional demo artist,” who specializes in presenting the software in the best light. However, it is essential to

- be cautious; what is often shown may not be the actual system being considered for purchase, but a more polished or simplified version designed to impress.

- Scripted. In contrast to traditional demos, scripted demonstrations are more structured. The client provides a list of specific requirements or functionalities they wish to see during the demo. Vendors receive this list in advance, which allows them to prepare adequately. While this format offers a more targeted approach and ensures that key features are showcased, it is essential to note that these demonstrations are often also conducted by professional demo artists. Consequently, although the DOT gets to see functionalities important to the agency, it might not be the actual working system but a prepared scenario that the vendor knows well.

-

Verification. Verification demonstrations are distinct because they focus on showcasing a product that is already in use. This is neither a “sandbox” nor a “demo” system; it is the actual system being proposed for the project at hand. In this setup, the vendor coordinates with an existing client who is currently using the product. Representatives from this client execute the script or demonstrate the software, providing authentic insights into its real-world capabilities and limitations. This type of demonstration offers the most realistic perspective but also requires the most coordination and planning to execute successfully. When using this approach, consider the following procedures:

- – Create a maximum of eight to 10 specific problem scenarios that the new system should address and ask the vendor how their solution can resolve these issues.

- – Organize live demonstrations, either in person or via video conferencing. Allow for hands-on experiences following the live demo.

- – If a vendor claims their product has a specific capability that the evaluation committee is unsure of, make sure the vendor includes that feature in the demonstration for verification.

Figure 13 summarizes the pros and cons of each software demonstration method.

Each type of software demonstration comes with its challenges, and the best choice often depends on the specific needs and constraints of the client. Traditional demos are the most straightforward but may not provide an accurate representation of the product. Scripted demos offer targeted insights but are also often “staged” to some extent. Verification demos provide the most authentic experience but can be logistically challenging to arrange. Understanding these nuances can help DOTs make an informed decision about which demo type is most suitable for their unique requirements.

There are different ways to evaluate technology demonstrations. For example, when evaluating connected vehicle signal phasing and timing deployment, DOTs provided a series of test cases for proposing vendors to perform. A score of 0 points was given for any test case where the vendor failed to pass, whereas passing each test case resulted in full points being awarded. The RFP also

allowed for a verbal interview (oral presentation) which asked vendors to address (a) the project approach for furnishing, installing, integrating, testing, and training; (b) the project team and work plan; (c) the technical and functional requirement description, including equipment certification; and (d) the training approach and resources for technical support.

Factors for Success

If the DOT agrees to a verification-style demo, it is important to understand the challenges often associated with software demos:

- Vendor relationships pre-RFP. Vendors often establish strong relationships with potential clients before the RFP process. To address this, the evaluation committee should review and document these relationships to ensure transparency and fairness in the evaluation process.

- Evaluator research. Evaluators may independently research vendors and products, and thus bring in their biases. To manage this, evaluators should disclose their experiences and potential biases before participating in the evaluation process.

- Vendor resistance. Vendors might resist specific demo requirements, especially those they find cumbersome or detrimental to showcasing their product. Clear communication and justification of these requirements by the evaluation committee can mitigate resistance.

Consider the following procedures when conducting software demos:

- Pre-educate the vendors. The evaluation team should set expectations by educating vendors multiple times on the verification process. This upfront effort aligns all parties on the purpose and scope of the demo.

- Time efficiency. Keep demos concise, aiming for a 1- to 1.5-hour window. This ensures focused engagement from all parties and avoids information overload.

- Concurrent interviews with the implementation team. Conduct interviews with the implementation team at the same time to provide a broader perspective and allow for more in-depth evaluations.

- Streamlined RFP and evaluation process. The evaluation committee should ensure a well-structured RFP and evaluation process. The more streamlined and reliable this process is, the smoother the verification demos will go.

- Multiple pre-education sessions. Organize multiple pre-education sessions to ensure vendors fully understand what is expected in the verification demos.

Debriefings

The debriefing process in the RFP administration is crucial for maintaining transparent and professional relationships with vendors. A well-conducted debriefing can offer valuable insights into why a vendor was not selected, pinpointing areas of weakness and opportunities for improvement. This practice not only helps vendors for future proposals, but also prevents misconceptions that could lead to a poor reputation for the client, low response rates for future RFPs, or even protests alleging process violations.

The traditional approach often involves sending a letter to inform vendors they were not selected, and require them to request additional information. A better approach is to include a summary sheet with the initial notification, which vendors could otherwise access via the Freedom of Information Act. The summary sheet could include information such as the vendor’s overall ranking/score, the average scores of all the proposers, the number of proposers, cost details, and more. This proactive communication is appreciated by suppliers and typically reduces the need for a formal debriefing, thereby saving time for the buyer. Debriefing materials should be prepared in advance and transparent, aiding vendors in their continuous improvement while maintaining the integrity of the selection process.