The Language of Life: How Cells Communicate in Health and Disease (2005)

Chapter: 1 Small Talk

1

SMALL TALK

In broad daylight, you are floating in darkness. You swim in silence because you cannot hear. On your right, a cloud of sugar molecules drifts just a few centimeters away—dinner, but how will you find it? On your left, a noxious chemical seeps toward you—but unless you know that you’re in danger, how can you escape? If you are the bacterium Escherichia coli, sharing space in the human gut with other indigenous flora and fauna, this is your world: unpredictable, at times even inhospitable. But don’t dwell on your limitations. Your kind came to life when the earth was still hot and sulfurous and has used the intervening eons to craft all the tools and techniques you need to survive in a capricious environment.

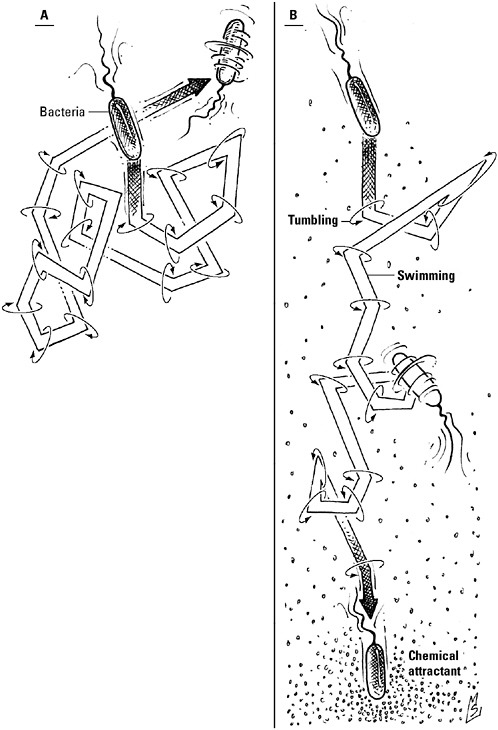

You have many talents. For one thing, you can move. Let the bottom dwellers and the stone huggers ache to be noticed by some passing current; evolution taught you to waltz—chassé, pause, spin, glide, ONE-two-three, ONE-two-three, left, right, zigzag. Your dancing shoes are a skein of protein filaments, or flagella, powered not by muscles and tendons but by a gearbox of proteins that operate as a rotor, twirling the flagella at more than 100 revolutions per second. When the rotor turns counterclockwise, the flagella spiral

into a single tail and you glide in a smooth, straight line. When it spins clockwise, the flagella unfurl and stroke, each to its own beat, and you spin and tumble in place. Reverse again and you resume swimming in a new direction. The rotor switches back and forth as regularly as a metronome, spinning one way for a few seconds, then the other. Spinning and swimming, you meander along to its rhythm, improvising a daydream of a dance that textbooks refer to as the “random walk.”

It’s a good thing you don’t have a mother—she’d surely admonish you to watch where you’re going. You can’t afford to be so oblivious, she’d scold, or you’re liable to waltz right into trouble. As neurobiologist Rodolfo Llinas warns human ramblers, “Active movement is dangerous in the absence of an internal plan subject to sensory modulation. Try walking any distance, even in a well-protected, uncluttered hallway, with your eyes closed. How far can you go before opening your eyes becomes irresistible?” But you could tell her not to worry—you can chart a less haphazard course when you need to. Should an appetizing snack appear on the horizon, the rotor lingers in counterclockwise mode, so that you swim straight ahead, in the direction of the meal, instead of meandering aimlessly. A distasteful substance, on the other hand, shifts the rotor clockwise, and you tumble in search of an escape route—the path you’ll follow when it resumes its usual alternating pattern.

By repeatedly adjusting the proportion of clockwise-to-counter-clockwise rotation, you can forego your wandering ways in favor of a one-step forward, one-step-sideways shuffle—not exactly what a more advanced creature might think of as purposeful movement but a “biased random walk” that hitches determinedly, if somewhat erratically, toward satisfaction or away from catastrophe. Microbiologist Ann Stock explains: “If the cell finds itself moving in the proper direction, it suppresses tumbling and moves further in that direction. Then it randomly reorients and heads off in a new direction, one that might still be good or may now be bad. If it’s going in the

E. coli, out for a walk. In the absence of an attractant (an edible amino acid, oxygen) or a repellant (distasteful metal ions, for example) stimulus, the bacterium alternates randomly between periods of tumbling in place and smooth swimming by switching the direction in which its flagella rotate (A). Should E. coli detect a chemical signal, however, the information will be relayed to the motor turning the flagella, causing the flagella to rotate preferentially in one direction. Here (B), an attractant has encouraged rotation in the counterclockwise direction; as a result, the bacterium swims more than it tumbles, moving in the direction of the food source.

wrong direction, it goes back to tumbling. It seems tortuous, but the same patterns are used by grazing animals to find better pastures. You do a little sampling in all directions and keep going when things are good and reorient when they’re not.” But how did you determine which direction was the “right direction”? And how did you use that information to change the rotation of your flagella?

I look and listen and touch; if I could swim with you, I would know the human gut as wet and warm, a muffled rush of murky water. But there are other ways to experience life. Your world is vivid with chemicals as well as colors, molecules as well as sounds. They could be your connection to the outside world, the cues that could chart your path. Even this solution presents difficulties, however. Like other cells, you are surrounded by a protective membrane of lipids and proteins isolating your fastidiously composed internal fluids from the unpredictable excesses of your surroundings. Nothing that might upset the delicate balance critical to life can penetrate this barrier—but neither can the chemical signals bearing news about current events. Inside your hermetically sealed bubble, the rotor proteins controlling your flagella are waiting for direction; outside, messengers with the information needed by the rotor proteins mill restlessly in front of closed doors.

Troublesome organism, isn’t there any end to your problems? Evolution should have just given up on you, allowed you to starve in silence. Instead it has crafted words to describe your world and rules for combining them, the building blocks of a language that tells you how to move in step with the world around you and gives your crooked walk a glamorous name: “chemotaxis,” movement directed by chemicals.

BETTER MOVEMENT THROUGH CHEMISTRY

The ancestors of E. coli did not have plastics, but they did have another type of polymer suited to a wide range of applications: proteins. More heterogeneous than polystyrene or polyurethane, nature’s

megamolecules are combinations of 20 different building blocks, or amino acids, coupled to each other by the electron-sharing arrangement known as a peptide bond. Man-made plastics can be shaped, molded, or extruded to order, but protein polymers automatically bend themselves into useful shapes, guided only by their affinity for water and the social relationships between their constituent amino acids—no heat or specialized machinery required.* Scores of fragile alliances between amino acids act in concert to stabilize the folded protein, resulting in a three-dimensional configuration as unique as a fingerprint.

Productive only when wedded to another molecule, the protein relies on this structure to play the role of matchmaker, embedding an advertisement for a soul mate in the loops, bulges, and trenches created on its outer surface by the folds:

“Are You My Better Half?”—SFP (single folded protein) with secure position in healthy cell seeks compatible molecule with interest in chemical engineering, architecture, or communication for exclusive short-term relationship. Please reply with details of your chemical structure.

The molecule with the most compatible profile wins the date and enters into a marriage of convenience, arranged by evolution to accomplish a specialized task. Paired with a matching substrate, an enzyme speeds up a vital chemical reaction. A rotor protein and a flagellar protein conspire to move a bacterium. And a protein with a soft spot for a nutrient or a toxin (call the partners “receptor” and “ligand”), as well as a torso rich in water-repelling, or hydrophobic, amino acids on intimate terms with the lipid-rich plasma membrane, is the perfect spy, relentlessly drawn to important information and

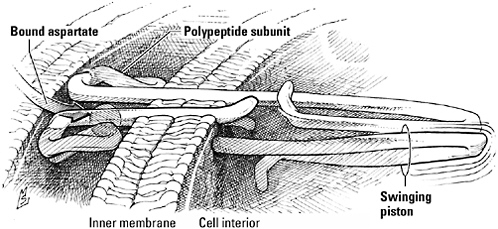

The Tar receptor. The binding site of this sensor protein, which can detect both the amino acid aspartate and repellants such as nickel, projects above the outer surface of the plasma membrane. A mobile helical segment spanning the membrane acts as a “swinging piston” that nudges the first member of an intracellular team of proteins charged with relaying the news to the flagella.

built to share that information with an insider able to put it to good use.

E. coli sponsors five such receptor-ligand partnerships—its five senses. The receptor that biologists call “Tsr” is married to the amino acid serine. The Tar receptor’s partner is aspartate. Tap prefers peptides; Trg falls for proteins that bind and transport the sugars ribose and galactose. Aer is devoted to oxygen instead of nutrients. To conserve precious space in a small genome, adultery is not only permissible but encouraged; Tar, for example, has leave to consort with repellants, such as nickel ions, in addition to aspartate.

The architecture of the receptor determines how it will speak as well as to whom it will speak. Look, for example, at the Tar receptor in cross section (you can’t, of course, but X rays or the magnetic field generated by a nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer can), and you’ll see that it’s not a single protein but a dimer (pronounced “DIE-mer”)—a pair of identical polypeptide subunits. Note how each rears up out of the membrane like a flower, crowned with a rosette of four helical segments that cradle Tar’s preferred ligands. Two of these heli-

ces wind out of the binding site and through the membrane, tapping into the rich cytoplasm below. Rooted, Tar is not rigid, however. During the subtle shape-shifting triggered when receptor and ligand embrace, one transmembrane helix is pushed downward and forward. The kick delivered by this “swinging piston” transmits news of the binding of attractant or repellant from outside to inside; in effect, Tar uses its own body to announce the discovery of ligand, much as an electronic sensor might activate a buzzer or a flashing light.

In an organism as small and simple as E. coli, one word (or one nudge from a dangling helix) should be enough to tell a rotor “left” or “right.” But this bacterium must have had a finicky language

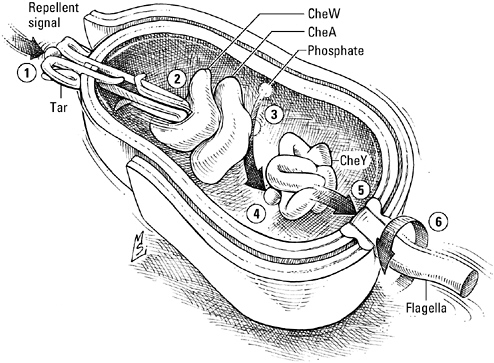

A bacterial “sentence.” The binding of a repellant signal to the Tar receptor (1) sets the helical piston swinging (2), prompting CheW, the “word” heading the intracellular portion of the sentence, to activate the kinase CheA (3). This enzyme transfers a phosphate group to CheY (4); phosphorylated CheY (5), in turn, tells the rotor protein, currently turning counterclockwise (6), to change direction.

teacher, for it insists on speaking in complete sentences. The receptor is the subject of this sentence, the predicate a team of intracellular molecules called “Che” (for chemotaxis) proteins that relay the message from receptor to rotor and add the nuance of context. CheW, the team member that heads this bucket brigade, is merely a go-between. When Tar detects a repellant, CheW takes the kick, then pokes the next protein in line, CheA, the action verb at the core of every chemotactic sentence.

One of a large and influential family of enzymes known as “kinases” (from a Greek word meaning “to move”), CheA, like its kin, responds to a wake-up call with an expletive—“Phosphate!” The chemical group that puts the “P” in ATP, phosphate, bristling with three negative charges, has the power to twist proteins inside out, turn ordinary amino acids into powerful magnets, and disrupt long-standing relationships—a switch flipping switches. “Nickel! Pass it on,” whispers CheW, and the excited kinase spits a phosphate group into the face of one of its own histidine residues. The histidine, in turn, spews it at the nearest bystander, an aspartate protruding from the final protein in the relay, CheY. To CheY, phosphate is not an insult but the gift of wings. It soars across the cell, landing on the rotor protein. “No more swimming!” it bellows. The rotor obediently shifts into clockwise mode. Flagella flail, and the bacterium spins like a child on a tilt-a-whirl.

The news of aspartate binding outside the cell travels via the same protein relay but has the opposite effect. Instead of agitating, the receptor tells CheW to tell CheA to keep its mouth shut. The kinase dozes; CheY stays home and keeps to itself. And without phosphorylated CheY meddling with the rotor, the bacterium continues to swim, gliding smoothly toward the food source.

Writers are admonished to be sparing in their use of adjectives, but E. coli shamelessly adds two modifiers to every chemotactic sentence. Such verbosity isn’t a sin in this language, however—the extra words, the enzymes CheR and CheB, add contextual information

the bacterium needs to fine-tune responses, in the form of methyl groups ( a “methyl group” is a chemical “special teams” unit consisting of a carbon atom surrounded by three hydrogen atoms) that they plug in to or pull out of sockets in the tails of chemotactic receptors. Whenever the binding of an attractant stills the receptor and quiets CheA, CheR inserts methyl groups into the sockets; with each addition, the receptor recovers more of its voice. The binding of a repellant, on the other hand, prompts CheA to activate the CheB enzyme along with CheY. Phosphorylated CheB unplugs methyl groups, hushing both receptor and kinase. By adding and subtracting methyl groups, the two enzymes can adjust receptor sensitivity to mitigate the effect of ligand binding. “You can think of chemotaxis receptors as sitting in a balance between the ligand binding state and the methylation state (that is, the number of methyl groups attached to the receptor protein),” explains Ann Stock. “When the two are properly balanced, you have a steady state output. If you add a stimulus, you throw the receptor into a new signaling state, where you get some sort of response. Then, if you change the methylation state to counterbalance the presence of ligand, you restore the initial steady state output.” This balancing act, known as adaptation—the bacterial equivalent of the adjustment your eyes make when you walk out of a dark room into bright sunlight—links the response to a change in the amount of ligand, rather than concentration per se, extending the range of the chemotaxis system over five orders of magnitude.

Methylation not only keeps bacteria alert but also makes them smarter; in addition to volume control, it serves as a primitive form of memory. A physical record of the bacterium’s most recent interaction with the environment, the methylation state of the receptor records the concentration of attractant or repellant. Then, a few strokes later, the organism can reference this value, compare it to the current level of stimulation, and engineer a midcourse correction if necessary. Stock concludes: “The cell is testing out its environment at one point in time. It’s swimming, it’s moving to a new place,

comparing. And then it makes the decision whether to go forward or tumble based on what has happened over time.”

“The modern era begins, characteristically, with a revolution,” writes historian Jacques Barzun in From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life, referring to the cultural upheaval that began with Martin Luther’s challenge to the Catholic Church. However, as Barzun notes, this cataclysm did not simply erupt out of the blue. The influence of earlier reformers and critics, the invention of the printing press, the introduction of higher-quality paper and ink, and the emergence of skilled printers provided the ideas and tools necessary to transform a local protest into an international spectacle.

Come here. Run away. Just as the Protestant reformation had its roots in the earlier efforts of Wycliff and Gutenberg, the revolution in communication that would one day guide interactions between cells almost certainly had its origins in simple directives like these, governing interactions with the environment. Pioneered by a distant ancestor fortunate enough to stumble upon the virtues of proteins for engineering alliances between molecules, the chemotactic sensory apparatus of bacteria like E. coli illustrates fundamental principles common to the transfer of any type of biological information via chemical signals: the exploitation of protein topography to discriminate signals; the use of transmembrane receptors to circumvent the barrier posed by the plasma membrane; the coordination of perception and response, as well as the integration of multiple signals, by means of protein relays featuring kinases; the regulation of receptor sensitivity by chemical modification. Using these principles as a template, evolution would construct a chemical language that would end the isolation of cells, that would allow them to talk to one another, to cooperate, to live as a group yet behave as a single organism—one of the most extraordinary achievements in the history of life.

GROUP DECISIONS

“You want a crab?” A skinny boy of about 10 holds a saucer-sized crustacean by a front claw and shakes it at me.

“That’s a big one. You’re not taking it home?”

His mother, who is trying to persuade his younger brother to pick up the sand castle paraphernalia, looks up and glares at me. “It already smells,” she hisses. Behind her, two hungry seagulls nod in agreement.

“Sure,” I reply, and hold out a small plastic bucket.

Back at our beach blanket, my 13-year-old daughter Haley looks up from the latest issue of Teen People and peers into the pail. “Why do you have a dead crab?”

“It’s not dead; it’s just not moving.” I prod gingerly at the crab with the end of a pencil, but it has turned peevish and uncooperative. It squats at the bottom of the pail like a sullen garden toad, refusing to budge. I poke more aggressively. Without warning the stalks supporting the crab’s beady black eyes shoot straight up at me. “Ahhh! Did you see that? It popped its eyes at me!”

“It’s being weird because it’s in a bucket of hot water,” Haley remarks, turning the page.

“I was going to draw its picture, but I think maybe I’ll just let it go. Would you like to help me?” I ask.

We pick a spot near a rocky outcrop, checking first for the gulls. When I’m certain they’ve moved on in search of other prey, I tip the pail into the surf. Torpid in captivity, the crab dances in the saltwater, energetic as a wind-up toy. It punches at the foaming wavelets, scrambles along the edge of the rocks, cartwheels, hops. It clutches at the slippery rocks. Finally, it darts sideways into a crevasse and disappears, safe at last from hungry gulls and grasping humans.

Dozens of species of marine bacteria also call this tidal flat home—and they don’t take any more kindly to deportation than my crab. Relocated to the laboratory, most die, no matter how attentively they’re coddled. Microbiologists at Northeastern University

suspected this failure to thrive was not the result of bumps and bruises incurred during the move itself but of homesickness afterward; to prove it, the researchers decided to culture the beach along with the bacteria. They cut out a block of beach sand and isolated the resident bacteria. Instead of transferring the microbes to petri dishes, however, they corralled them in small diffusion chambers formed by sealing a washer between two permeable membranes, placed them back on their native sand in a marine aquarium, and submerged the chambers in seawater, in effect “returning” the bacteria to the wild. Cultured the traditional way, less than 1 percent of the bacteria originally isolated would have survived; surrounded by the comforts of home, 22 percent, including two previously unknown species, not only survived but thrived.

In the laboratory incubator, it is never winter—but it’s not home either. “We’ve tended to use bacteria as model systems in the laboratory,” says Ann Stock. “But we realize now that the conditions that you keep them under in a laboratory don’t even come close to scratching the surface of the kinds of environments they find themselves in when they’re living in the real world.” For some species, like these marine microbes, the difference between their native environment and the lab environment is more than their fragile physiology can handle. Others are more resilient; a few, like E. coli, adapt so well, Stock notes, that it’s easy to forget they were once wild creatures. Unless culture conditions demand some effort, these domesticated bacteria find it easy to forget survival skills that were essential in the wild; after all, why waste effort on rotors and receptors when safety is a given and food is delivered regularly to your doorstep? If you don’t use it, it’s best to lose it. “There’s a tremendous selection for efficiency,” Stock observes. “We see all the time in the laboratory that cells will lose genes or the expression of genes and behaviors that you’d see in the wild-type environment because you don’t maintain selection for them.”

Shielded from the demands of the real world, many domestic

bacteria have not only lost their ambition but also mothballed a talent that until recently no one knew they even had—the ability to talk. Speechless in agar, bacteria at liberty in soil and pond water, milk and meat, the open sea, or the human body are not mute, but chatter relentlessly to each other, in chemical dialects that follow the same organizational principles as chemotaxis. They trade gossip. They sound alarms and plan invasions. And, most surprising of all, they form alliances, primitive communities that allow them to enjoy benefits—more efficient use of resources, access to environmental niches unsuited to single cells, safety from predators—once thought to be the sole province of “traditional” multicellular organisms like plants and animals.

“Certainly bacteria are the best-studied organisms,” says microbiologist Bonnie Bassler. “But they have always been considered to live these sorts of individualistic, asocial lives. And it’s just not true.” In their native environment, bacteria are social creatures, eager to collaborate and able to do so because, like more complex organisms, they have discovered that the key to civilization is communication.

Unlike E. coli, the roses beautifying my fence don’t have to watch where they’re going because they aren’t going anywhere. Plants, able to feed themselves by trapping sunlight, have sprouted roots instead of flagella and thrown in their lot with the soil. Staying put is a good way to avoid running into trouble but no way to meet members of the opposite sex. Enter the honeybee. In return for a contribution to its pantry—a share of the pollen and sweet nectar to be made into honey—it does the heavy lifting of reproduction for the rose, distributing pollen like love letters as it wanders from flower to flower. It’s a win-win proposition for everyone: the plant finds a mate; the bee feeds its brood.

In the moonlit shallows off the coast of a South Sea island, the Hawaiian bobtail squid Euprymna scolopes and the marine bacterium Vibrio fischeri have negotiated an equally beneficial arrangement.

Night is a dangerous time to trawl these waters. The squid’s shadow ought to give it away; instead, all a hungry fish sees is silver—Euprymna, bright as the moon, is invisible to its enemies, thanks to the hospitality it extends toward V. fischeri. In return for room and board in a sac on the underside of the squid’s body, V. fischeri produces an enzyme, luciferase, facilitating a chemical reaction that releases energy in the form of light. The luminescent bacteria ensconced in the light organ enjoy a free meal, while the illuminated squid avoids becoming someone else’s.

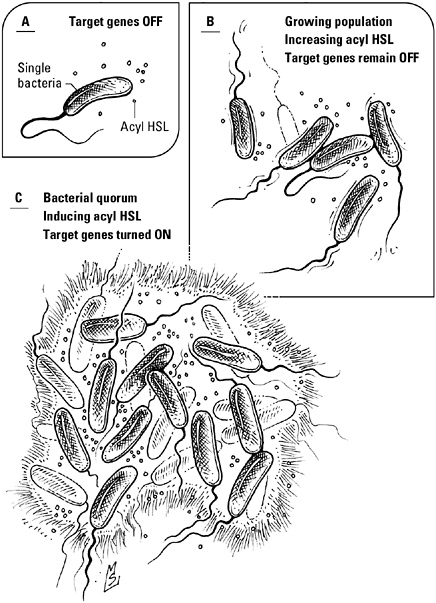

Keeping the lights on all of the time is expensive, whether you’re paying for kilowatt-hours or burning food to synthesize light-making enzymes. When it’s on its own in the open ocean, therefore, V. fischeri hides its lights under a bushel, switching off the luciferase gene until it’s inside the light organ of a cooperative squid. The bacteria “know” when they’ve reached this safe haven the same way teenage girls know when they’re at the “right” party—all of their friends are there. V. fischeri, of course, can’t take a head count by cell phone. But it can secrete chemical messengers to advertise its presence, and it can listen for signals secreted by others, drawing on the same principles underlying simple sensory mechanisms for keeping track of the physical environment to develop similar mechanisms for keeping track of the social environment.

In the language of V. fischeri, the word for light is “N-(3-oxohexanoyl)-homoserine lactone.” Non-native speakers are welcome to use the colloquial term “autoinducer,” coined by Harvard researchers Kenneth Nealson and John Woodland Hastings, when they proposed, over 30 years ago, that a chemical substance synthesized and secreted by the bacteria themselves cued the expression of the luciferase gene. Even that’s a large word for a molecule so small the plasma membrane poses no barrier to it—it leaks out of the bacterial cell almost as fast as it’s made—and it’s being made most of the time, because V. fischeri has a habit of muttering to itself more or less constantly, even when no one’s listening. In open water, where

individual cells are rarely in close contact, the signal is diluted so much that by the time it reaches the nearest neighbor it’s inaudible. In the cramped quarters of the squid light organ, however, where as many as 10 billion bacteria crowd together, concentrations of autoinducer swell to cacophonous proportions, sending an unmistakable message to every member of the group: “You are not alone.”

The chemotaxis signaling mechanism employs a relay of proteins, but V. fischeri is terser; the sudden flood of autoinducer molecules activates a dormant protein, LuxR, that is both receptor and response regulator. CheY is only a lowly mechanic, fiddling with a rotor. LuxR is an artist, the genome its medium. One of an elite class of proteins known as transcription factors, it has permission to turn genes on and off: luciferase—on; luxI, which encodes the enzyme responsible for synthesizing the autoinducer—on; luxR, the receptor gene itself—off. The production of signal and light, increased by LuxR, is simultaneously tempered by a compensatory decrease in receptor number, allowing V. fischeri to fine-tune the light response, just as the addition and subtraction of methyl groups allow E. coli to adjust the sensitivity of chemotaxis receptors.

A single bacterium can generate only a pinpoint of light. But a group of bacteria, operating as a team, can produce enough light to forge a mutual defense pact with a larger organism. “It’s mob psychology,” quips Bonnie Bassler, but it’s also a model of parliamentary procedure: all decisions are deferred until a requisite number of voters can be assembled. “If the bacteria wait, and they count themselves, and then they all do it together, they can have an enormous impact and frankly overcome tremendous odds,” she continues. Known to microbiologists as “quorum sensing,” this show of hands allows the group to “organize [itself] to act like a huge multicellular organism,” reaping the attendant advantages of cooperative living as a consequence.

The recipient of a 2002 “genius” award from the MacArthur Foundation, Bassler began working on quorum sensing a decade ago,

Quorum sensing—a bacterial discussion about light. The bacterium V. fischeri emits a chemical signal, known as an acyl HSL, to announce its presence to others. In the open sea this signal rapidly dissipates (A). Within the confines of the squid light organ, however, the concentration of acyl HSL increases as the number of bacteria increases (B). When the concentration reaches a threshold level, the signal triggers the expression of genes encoding the proteins responsible for the light-generating chemical reaction (C).

when most biologists thought of V. fischeri as a freak of nature, its discussions of population density no more than “an odd anomaly of these interesting but not very important glow-in-the-dark bacteria from the sea. It was considered fringe science,” she recalls. Today, quorum sensing is hot gossip, thanks to research by Bassler and others demonstrating that V. fischeri isn’t the only species counting with chemicals. “All bacteria probably do what it does,” she maintains. “And they don’t just turn on light; they turn on all kinds of functions that make sense for bacteria to express when they’re in a community but not when they’re alone. There’s an enormous range of behaviors besides luminescence that are regulated by cell-cell communication.”

More than 50 other species of Gram-negative bacteria (so named because of their reaction to a commonly used staining procedure) count out loud by releasing chemicals similar to V. fischeri’s autoinducer, known collectively as acyl homoserine lactones—acyl-HSLs for short. In nearly every instance, a LuxI-like enzyme synthesizes the acyl-HSL signal, which is detected and translated into action by a LuxR-type receptor/transcription factor controlling critical genes. But as Bassler says, not everyone is interested in discussing how to make the world a brighter place. Many—take Pseudomonas aeruginosa, for example—are busy plotting murder and mayhem. This deviant, which preys on the injured and the immunocompromised, brings weapons instead of light when it comes to visit: so-called virulence genes, encoding proteins that allow it to stick to, penetrate, and poison host cells. But if P. aeruginosa launches its attack before the expeditionary force has multiplied into an army, it risks tipping off the victim’s immune system. Communication by quorum sensing helps the bacteria time the release of their virulence factors to coincide with a critical population density, evading detection until the cohort is large enough to take on the defenders and win.

Gram-positive bacteria, such as the common soil microbe Bacillus subtilis, also count heads. In the dark, damp earth of the forest

floor, B. subtilis relies on quorum sensing, in the context of current economic conditions, to choose between two retirement options. In well-to-do communities, the quorum opts to stay put and maintain the family home, promoting each other to “competent” status, in which everyone can activate genes for the machinery needed to scavenge DNA fragments from dead colleagues and repair defects in their own genomes. Bacteria confronted with a dwindling food supply, on the other hand, call for hibernation and migration. Neighbor croons to neighbor a chemical lullaby that puts everyone to sleep as spores, until fresh provisions arrive or a passing creature, a breeze, a storm-instigated rivulet sweeps them off to greener pastures.

Acyl-HSL isn’t spoken here, however. B. subtilis and other Gram-positive bacteria have their own way of saying things, in oligopeptides, short chains of amino acids cut from larger proteins and shipped out of the transmitting cell on the back of a dedicated transport protein. Instead of an all-in-one receptor/response regulator, Gram-positive bacteria are equipped with a “two-component” signaling relay, consisting of a receptor that is also a histidine kinase and a second protein that is a transcription factor. Well-fed bacteria say “Com X,” and the binding of oligopeptide and receptor leads to the phosphorylation of the transcription factor, enabling it to activate competence genes. Starving bacteria call out “CSF,” and everyone curls up into a spore. Skillful communication promotes sensible decisions; in times of plenty, the bacteria maintain the integrity of their genomes instead of languishing as spores, while in the face of imminent catastrophe, they postpone rebuilding and hunker down to weather the crisis.

Life may have begun as a single cell, but it did not stay that way for long. “Several hundred millennia ago, prehistoric humans learned that there is strength in numbers,” Bassler and colleague Stephen Winans note in a recent review, but “bacteria made this discovery at least a billion years earlier,” a discovery destined to preside over the

birth of cooperative behavior and social organization. Just as “the evolution of language likely aided in the ability of protohumans to coordinate the behavior of the group,” the evolution of chemical signaling—quorum sensing—facilitated the emergence of group behavior in bacteria. As a result, they argue, quorum sensing is not simply a bacterial idiosyncrasy but “one of the first steps in the development of multicellular organisms.”

THE TALK OF THE TOWN

“Now the whole earth had one language and few words.” According to the biblical account of the Tower of Babel, the human race wouldn’t need translators if it weren’t for a few arrogant architects—we’d all still be speaking the same language. Instead, a bewildering array of at least 6,000 different tongues and regional dialects confounds international communication, impedes commerce, and undermines diplomacy. No wonder enterprising wordsmiths have tried to create a “universal language” that would allow speakers of English and German, Pashto and Hindi, Swahili and Tagalog to talk freely with one another. One of the best known—and arguably the most successful—of these artificial languages is Esperanto (meaning “one who hopes”), created in 1887 by a Polish doctor, Ludwig L. Zamenhof. An amalgamation of Latin, Romance languages, German, English, Greek, and Slavic, Esperanto features a simple, law-abiding structure devoid of the irregular verbs, gendered nouns, and arcane spellings that plague natural languages; as a result, aficionados claim, it’s five times easier for a native English speaker to learn than French or Spanish, 10 times easier than Russian, and 20 times easier than Chinese.

Perhaps bacteria, unable to build towers that offend deities, have been rewarded for their humility. Perhaps they have simply been prudent closet cleaners, careful as they updated and revised their genomes over millions of years, not to lose their universal language,

chemical signals understood by all, in addition to the secret dialects each species uses to talk to its own kind. Despite its carefully engineered simplicity, Zamenhof’s Esperanto can count perhaps 2 million speakers worldwide, but this “bacterial Esperanto,” as Bonnie Bassler calls it, may boast millions of speakers in a square centimeter, all of whom were born knowing it. Invaluable in a world teeming with strangers, these universal signals enable bacteria to ask not only “How many?” but also “Who are you?”

If you want to be a molecular geneticist, why not make your life easy by studying an organism that’s small, economical, and doesn’t bite, that has only one chromosome, and that spawns a new generation every 20 minutes? And if you want to make the job even easier, why not go one step further and select a microorganism that has a heritable trait you can study with the naked eye simply by turning out the lights? That’s why Bonnie Bassler chose Vibrio harveyi.

Bassler’s affection for seafaring bacteria began in graduate school, when they rescued her thesis. “I was working on a project that involved chicken cells and it was going nowhere. Then my thesis advisor got a small grant from the Navy to study how bacteria adhered, because when boats get barnacles on the bottom, the first thing that happens is you get bacteria sticking to the surface. So he handed me a little vial of marine bacteria and told me to figure out how they stick,” she recalls. Afterward, when she wanted to master the tools and techniques of the DNA trade, the incandescent talents of marine Vibrio species again made them the perfect lab partners. “As a wannabe geneticist, if you’re going to make mutants, all you have to do is turn out the lights in the room and see if they don’t make light or if they glow when they shouldn’t. This is perfect for me because what could be easier?”

Bassler came to the Agouron Institute in La Jolla, California, to work with Mike Silverman, the “one person who was doing genetics in these wild bacteria” as well as the pyrotechnician who had spearheaded the effort to identify the components of V. fischeri’s LuxI/

LuxR quorum-sensing mechanism. Under his direction she used a similar approach to dissect V. harveyi’s quorum-sensing system and discovered that it had a different way of talking about light. In contrast to V. fischeri, this Gram-negative bacterium ferried messages to genes via a two-component relay like that found in Gram-positive species. And it secreted a second autoinducer—but this one, christened simply “AI-2,” wasn’t an acyl HSL. What sort of molecule it was, no one could say, because AI-2 resisted purification and defied every attempt to determine its chemical structure. Scientists may have been mystified. Among bacteria, however, Bassler discovered that AI-2 was common knowledge.

Now with her own lab at Princeton University, Bassler and a new team of co-workers cloned the gene responsible for producing AI-2, and, as is common practice, compared their sequence to that of other bacterial genes on file in public databases. To their surprise, the search uncovered a nearly identical gene in more than 40 other species of bacteria, Gram-positive as well as Gram-negative, including a “list of the clinical ‘Who’s Who’ in pathogenesis”: Vibrio cholerae, the cholera-causing black sheep of the Vibrio family; several Salmonella and Streptococcus species; the respiratory pathogen Haemophilus influenzae; Borrelia burgdorferi, responsible for Lyme disease; Helicobacter pylori, maker of ulcers; and Yersinia pestis, infamous as the causative agent in bubonic plague. “As far as we can tell,” says Bassler, “they’re all making the identical molecule. In the acyl-HSLs, the acyl side chain differs from bacterium to bacterium, and that confers exquisite species specificity. We think this is more of a universal language.” In fact, she suggests, AI-2 may be one of the oldest and most familiar words on earth. Because it’s spoken by both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, it is likely to have evolved before the two lineages diverged—and before they began speaking in acyl-HSLs or oligopeptides.

Not only did Bassler determine that AI-2 is a universal signal, she finally solved the mystery of its chemical composition. She knew

that the synthesis of AI-2 began with a compound that cells often turn to when they need methyl groups, S-adenosylmethionine. And she had learned that an enzyme, LuxS, finished the job, but wasn’t a meticulous chemist. The floppy carbon skeleton that was LuxS’s handiwork could be folded in several different ways. So-called pure preparations were actually a mixture of all these configurations, only one of which was the structure preferred by living bacteria. “It was like sludge,” says Bassler. Then she came up with the idea of using the AI-2 receptor—which could be purified—to trap the correctly folded AI-2 signaling molecule. “We wondered, ‘Couldn’t we take the receptor to go into this mix and pick out the right structure?’ So my colleague and friend Fred Hughson crystallized the sensor protein bound to the true autoinducer. That’s how we got the picture.” The “picture”—the chemical structure of AI-2, as revealed by X-ray crystallography and mass spectrometry—resembled a pair of pentagons glued long end to long end and riveted together at the top by an unusual bolt: a boron atom. This was the quirk that had foiled so many previous attempts to identify AI-2. “Boron has had this mystery role in biology,” explains Bassler. “It’s known that boron is required by all these different organisms, but no one knew any reaction that it was involved in until this one. It’s like brand-new chemistry.”

Examination of the synthetic path from S-adenosylmethionine to AI-2 also suggested why this particular molecule might have been available to so many kinds of bacteria: its synthesis provided a solution to the universal problem of what to do about S-adenosylhomocysteine, the toxic metabolite left behind after S-adenosylmethionine relinquished its methyl group. “It’s a detoxification pathway,” Bassler notes. “The bacteria almost have to make it, because of this toxic intermediate.” In the process they inadvertently discovered a way to fashion a molecule with a message: I am.

Such self-aggrandizement led to grander things than counting family members. Bacteria that could speak in words understood by all could build relationships with other species, other cultures. They could build consensus. They could even build cities.

It’s a footloose existence, swimming and tumbling in a flask, through the gut, across a pond. But most bacteria are not nomads at heart; given a choice, what they really want is a place to call home, a refuge from the tiresome rush of air or water, where they can cling and congregate. A rock, a pipe, your teeth, plastic or glass, even the interface between a container of water and the overlying air, are potential building sites—provided they’re up to standard, because bacteria are as choosy about the neighborhood as any other potential home-owner. For some species a feast of sugars, or the perfect blend of amino acids, is the selling point, as compelling as an ocean view or award-winning schools. Some want fresh air, oxygen; some are drawn like a microscopic magnet to iron. Others need balmy temperatures or a particular salt concentration. How they would annoy a real estate agent, inspecting and rejecting neighborhood after neighborhood—warm, cold, luxurious, Spartan, salty, metallic, well aerated—in search of the illusive site that meets all of their demands.

“This is not a step they take lightly,” insists microbiologist Roberto Kolter. “Bacteria don’t just run into a surface. It’s a decision they make, to go and assemble themselves on that surface.” In his office at the Harvard Medical School, Kolter touches a key on his computer keyboard to start a video documentary he’s made that traces the natural history of one such settlement. Black dashes dart across the screen, like grains of wild rice shaken on a sheet of paper. They are house-hunting Vibrio cholerae—cholera bacteria—Kolter explains, and instead of poking their noses into closets or testing the faucets, they are probing the area with their flagella. “Individual cells will come and visit the surface for a while and then they leave. They haven’t committed to staying. But eventually, they make a decision. When the flagellum feels that it’s on that surface, it transduces a signal to the rest of the cell, and they begin to make the glue that sticks them.” He taps the screen with a pencil, pointing to a bacterium that has come to a standstill. “So this guy has made the commitment.” Seconds later he spots two more. “Or somebody around

here, this one. And now you see that another one has joined it.” Soon dozens have made similar decisions and settled down on the plastic surface.

This will be a family neighborhood now. It’s time to trade in the compact car for a minivan or for bacteria settling onto a rock or a pipe, to replace flagella with a mode of transportation better suited to solid ground—a grasping finger of cytoplasm that microbiologists call a pilus. Here’s how it works. Put your hand on a desk or tabletop and make a fist. Now, extend your index finger, bend your finger at the tip so you can grip the surface, and pull your hand up to your fingertip. Repeat—reach, grip, drag. Surface-dwelling bacteria use their pili like you’re using your finger, to crawl, or “twitch,” from place to place. And where might they be going? Why, to visit their new neighbors, of course.

On the screen, introductions are made by head-on collision, as two or three twitching bacteria slam into one another, run-ins that inaugurate enduring friendships. Traffic jams mature into cul-desacs. Chains of cells wind into tight spirals. The ties that bind these alliances are made of sugar, strands of sticky glycoproteins woven together to form a matrix that glues neighbor to neighbor and everyone to the surface. “They are like pioneers settling down to build a village,” Kolter says. “The matrix keeps them from swimming away.”

If a warm rock is a homestead, a warm rock dotted with such “microcolonies” is prime real estate. Families expand their territory, newcomers crowd in, late arrivals snatch the last parcels of open space. But there’s more going on here than a population explosion. Putting down roots inspires a level of cooperation and civic responsibility unknown in fluid environments. Neighbors who were strangers only hours ago now collaborate to erect buildings, construct roads, distribute food, establish defenses, and organize trade. By the time the day is over, this village will mature into a bustling, well organized metropolis, a social arrangement that researchers such as Roberto Kolter call a “biofilm.”

Step on a biofilm straddling a rock in a stream and all you’ll notice is a slippery scum. Fly over the surface with Roberto Kolter at the helm of a confocal scanning microscope—an instrument that uses a laser beam to scan a specimen one focal plane at a time and then integrates the slices to reconstruct a three-dimensional image—and you’ll get an aerial view of the skyline below the slime. Pillars and mushrooms jut up from the surface, high-rises that are home to millions of bacteria. A network of canals weaves around and between the pillars. These canals—in reality, fluid-filled channels dredged by growth-inhibiting secretions oozing from the bacteria themselves—form a primitive circulatory sytem, piping nutrients to those living in the high-rises and draining away dissolved waste products.

Cultural diversity and economic inequality, as characteristic of bacterial cities as our own, give rise to a patchwork of ethnic neighborhoods reflecting the uneven distribution of resources, regional differences in gene expression, and a willingness to accommodate multiple species. “In different areas of the biofilm, gene expression is different, so the bacteria take on different jobs. One guy is the cabinetmaker and one guy is the mechanic and one guy is the librarian,” says Bonnie Bassler. Kolter concurs. “Chefs and grocers may settle together in the restaurant district, while musicians may settle near concert halls,” he writes. For example, bacteria living near the surface of the biofilm, with easy access to oxygen and nutrients, are entrepreneurs, trend setters, lookouts. They grow and divide vigorously. Those with addresses in deeper layers, on the other hand, must make do with what little food and oxygen manage to reach the interior; the only job open to them is that of spore. But how do residents decide who is to explore and who is to sleep, where to erect a tower or dig a canal?

Silence is for pastoralists and loners. City dwellers need to talk. Bacterial cities print no newspapers and hold no public hearings, but chemical interchanges guide their behavior from the moment they begin to gather; as always, everyone’s favorite topic of conversation is

population density. Kolter explains: “The ones that stick signal to all of the others, ‘We are at high density, so we are going to be more committed to staying here.’” Within the microcolonies, quorum-sensing signals then direct the construction of the biofilm’s distinctive pillars and issue orders to excavate its interconnected canals.

Without signals, settlements cannot grow into species. Mutant bacteria, stripped of their ability to produce acyl-HSLs by genetic engineering, never progress beyond the microcolony stage. Instead of an orderly arrangement of towers and channels, these misfits, no longer capable of teamwork, pile on top of one another in an anarchic tangle devoid of architectural detail or social convention. Because biofilms are rarely the work of a single species—the plaque that forms on the surface of teeth, for example, may be home to more than 500 varieties of microbes—city residents have to know generic terms as well as their own species-specific dialect. “Acyl-HSLs are involved, but other signals are also important,” notes Kolter. Exchanges carried out in bacterial Esperanto—signals like Bassler’s AI-2—help strangers who speak different languages among themselves collaborate to define neighborhoods, assign jobs, and recruit passersby.

City living has many advantages. Food can be harvested more efficiently, distributed collectively. Walls repel barbarian invaders. A solid foundation is an anchor in a storm. But one day the food supply may run out, the stream may be flooded with pollutants, the host will die. When living conditions take a turn for the worst, biofilm residents issue new signals, telling everyone that it’s time to move on. Enzymes blowtorch holes in the web of glycoproteins, pillars and mushrooms collapse, channels dilate and then disappear, as clumps of bacteria pull free and swim away in search of greener pastures. Don’t think of this breakdown as a disaster—deconstruction is part of the natural life cycle of bacterial cities. “If the bacteria were unable to escape the biofilm, the biofilm would, like an old apartment building, become a death trap,” says Kolter.

Bacteria may live and work together as a biofilm as long as it’s expedient; heart and lung bond for life. Still, this community of one-celled organisms shares many features with the complex tissues of plants and animals: a characteristic internal structure, a division of labor, a developmental program, all choreographed by chemical signals. Through the artful use of tribal dialects and a chemical lingua franca, bacteria can transcend their humble origins and mimic the great civilizations of larger organisms.

A PATTERN LANGUAGE

In his books, The Timeless Way of Building and A Pattern Language, architect Christopher Alexander describes a “vocabulary” of design elements he believes are essential to the construction of towns, neighborhoods, and buildings in harmony with their surroundings, because they are “deeply rooted in the nature of things.” The words in this language are descriptions that Alexander calls patterns, configurations of architectural features that bear a particular relationship to one another:

In a gothic cathedral, the nave is flanked by aisles which run parallel to it. The transept is at right angles to the nave and aisles; the ambulatory is wrapped around the outside of the apse; the columns are vertical, on the line separating the nave from the aisle, spaced at equal intervals. Each vault connects four columns, and has a characteristic shape, cross-like in plan, concave in space. The buttresses are run down the outside of the aisles, on the same lines as the columns, supporting the load from the vaults. The nave is always a long thin rectangle—its ratio may vary between 1:3 and 1:6, but it is never 1:2 or 1:20. The aisles are always narrower than the nave.

A pattern is not a blueprint, however; it not only describes what a structure should look like but also reflects the events and activities that typically occur there. For example, “each sidewalk … includes both the field of geometrical relationships which define its concrete

geometry, and the field of human actions and events, which are associated with it.” Because it unites form and function, a pattern, says Alexander, represents a solution to a problem that “occurs over and over again in the environment.” And an ideal pattern is the best solution, one that describes “a property common to all possible ways of solving the stated problem … a deep and inescapable property of a well-formed environment.”

In our spoken and written language, nouns, verbs, adjectives, and other parts of speech—solutions to the design problems associated with converting thought and experience into sounds: the naming of objects, the representation of tense, the subtle nuance of description—can be linked in ways specified by the rules of grammar to form larger patterns, or sentences. Similarly, elemental architectural patterns—entrances, hallways, windows—can be combined to generate larger structures that maintain sensibility and harmony, provided they follow a prescribed set of rules, “patterns which specify connections between patterns.” A well-designed building, in other words, is like a grammatically correct sentence, an orderly arrangement of elements that “makes sense” because it follows the rules of this three-dimensional syntax.

In the turbulent incubator of a primeval world, the one-celled ancestors of all life forms conceived and nurtured ways to describe the physical world, as well as the social environment, in the language of chemistry. Chemical signals, and the machinery that cells evolved to detect and interpret them, became life’s parts of speech; the conventions observed when these elements were grouped to form pathways, the rules of biological syntax; the sequences constructed according to these rules, grammatically correct statements capable of informing behavior. This language, based on molecules rather than sounds—particularly proteins, folded, coiled, and looped into “configurations of architectural features that bear a particular relationship to each other”—has a three-dimensional aspect missing from spoken language. It is, in a sense, a pattern language, featuring design elements crafted from carbon and hydrogen rather than wood,

stone, or brick, which represent solutions to the problems encountered by cells as they evolved mechanisms to collect and transmit information about the outside world:

Problem: Finding the right words to start a conversation.

Solution: Make do with what you have. Cells didn’t have to look any further than their own doorsteps to find molecules, like S-adenosylhomocysteine, that could be recast as signals, or methods that could be co-opted to make new ones, like the protein technology that Gram-positive bacteria used to craft oligopeptides.

Problem: Say what?

Solution: Get in shape. Protein topography solved the problem of discriminating signals, with unique combinations of ridges, clefts, and loops that could easily tell serine from aspartate, an autoinducer made by the same species from an autoinducer made by a stranger.

Problem: The cell membrane.

Solution: The transmembrane receptor. Receptor proteins, with a sensor component to recognize the signal, a lipid-loving segment to insinuate it in the membrane, and a cytoplasmic component to broadcast the news of signal binding inside the cell solved the problem of ferrying information across an impenetrable barrier.

Problem: Delivering the mail.

Solution: Teamwork. Receptors could have been linked directly to the intended recipient of the message—a gene, a rotor protein. But cells found a more elegant solution in the relay, exemplified by the Che protein sequence of E. coli. Extra signaling proteins increase complexity but more than make up for the imposition by providing opportunities to amplify and regulate the flow of information along the way. And by mixing and matching receptors and relays, as E. coli does with its four receptors and one set of Che proteins, a cell can economize, creating multiple signaling pathways with fewer proteins—a feature exploited to maximum advantage, as we will see, by the cells of higher animals.

Problem: Staying alert.

Solution: Redecorate. An informant who chatters relentlessly stops being informative—and so would a signaling mechanism that could be turned on but couldn’t be turned down or turned off. A notch on a receptor or relay protein where a methyl group, a phosphate, or another protein could be attached allowed cells to fine-tune signal transmission. As a result, signaling pathways could remain responsive over a wider range of signal concentrations and react to changes in signal intensity rather than signal concentration.

Dogs and cats have devoted owners, horses and dolphins their aficionados. Bacteria have scientists like Bonnie Bassler and Roberto Kolter. To them bacteria are more than the occupants of the lowest rung on the ladder of life. “Bacteria are incredibly sophisticated organisms,” insists Kolter. “They have been evolving much longer than us. I don’t like the term ‘primitive,’ and I don’t like to think of bacteria as fossils. If you think of diversity as the number of genes, bacteria as a group have a hundred times more than animals, spread all over the planet. In this sense they are much more complex.”

Bassler agrees. “Everybody talks about them as being the simplest thing. I think they are the most sophisticated organisms. There’s just no slop. They’re perfected for every niche that they live in. They don’t have a nucleus or organelles, and they still do everything we do.”

Our bodies may be breathtaking in their sophistication, yet bacteria—life crammed into the smallest, most efficient package—have come up with the same answers to life’s most challenging questions. They use the same genetic code, live by the same metabolic reactions. And like our own cells, they talk to one another, using a chemical pattern language governed by a common set of grammatical rules. These conversations, an extension of sensory mechanisms developed to coordinate responses to environmental stimuli, allow them to socialize as our cells do, to build communities with many similarities

to complex differentiated tissues, and, in so doing, to enjoy improvements in the quality of life—better nutrition, more stability, safety from predators—that are the perquisites of multicellular living.

By exploiting the distinctive architecture of proteins and their affinity for a select group of signaling molecules, bacteria have crafted a language, talked their way to becoming the longest-running life forms on earth, and set the stage for more ambitious adventures in multicellularity. Words have changed and vocabularies grown but the basic syntax of the language of life—the signal-receptor-relay sequence illustrated in elegant simplicity by bacteria—has been conserved across kingdoms; it is also the foundation of the sophisticated biological sentences of higher organisms. A proven solution to a universal problem, this sequence and the elemental patterns that compose it truly describe “deep and inescapable properties” of communication in all cells.