The Language of Life: How Cells Communicate in Health and Disease (2005)

Chapter: 4 Life in the Balance

4

LIFE IN THE BALANCE

The weather report called for snow, followed by freezing rain, but, hey, that’s why you bought an all-wheel-drive vehicle in the first place. Still, you hadn’t counted on leaving the office so late, adding poor visibility to your difficulties. Clutching the steering wheel as the car hovers just above the road surface on a scrim of ice, you remind yourself how Consumer Reports extolled the safety record of this model. Suddenly, the minivan in front of you glides sideways. Your antilock brakes grind and grasp for a purchase. Only some feral instinct keeps you pumping the brake pedal and steering into the skid, so that you slide instead of spin. Until you’re in your own driveway, your heart’s in hyperdrive, you’re sweating like it’s July instead of January, your muscles have their own antilock brakes.

It’s easy to be dispassionate a few hours later, after you’ve had a cup of tea and warmed up, to tell your sister who called to see if you were safe that the trip was no big deal and sound as if you mean it. Nearly capsized by anxiety during the crisis, heart and lungs now clock along at their familiar steady pace, righted by some internal peacekeeper with a faultless sense of balance.

What impressed physiologist Walter Cannon most about the mammalian body was this inherent stability, that even though assailed by “the fell blows of circumstance”—winter storms and summer drought, accidents and predators, bodily injury (or the threat of it), hunger, thirst, overexertion, infection, and toxins—it was a model of constancy. “Confronted by dangerous conditions in the outer world and by equally dangerous possibilities within the body,” he asserted in his 1929 book, The Wisdom of the Body, mammals “continue to live and carry on their functions with relatively little disturbance.” Rather than simply hoping for the best, they have evolved mechanisms that allow them to resist stress by reacting to it. Cannon called this balancing act—“the coordinated physiological processes which maintain most of the steady states in the organism”—homeostasis.

Such stability, Cannon observed, is possible only because biological processes are so elastic. Often misconstrued as a sort of clamping mechanism that locks parameters like body temperature and heart rate at some constant value, homeostasis is actually a dynamic process. Pushed off center, the body pushes back, allows one parameter to deviate from the mean in order to return another to the range of acceptable values. But these corrective responses themselves must also be checked or they will push conditions too far in the opposite direction, placing a new set of excessive demands on delicate molecular machinery. An essential feature of homeostasis, therefore, is an intricate network of checks and balances meant to contain responses to stress before they spiral out of control.

Your “fight-or-flight” response to a skid on an icy road illustrates this action-reaction nature of homeostasis. Confronted with danger, the body marshals resources needed to fuel a getaway or mount a defense. The heart works harder and faster, an obedient liver mobilizes glucose, muscles tense in anticipation. Once the crisis has passed, however, there’s no need for internal organs to work so hard. Now the body puts on the brakes, setting in motion mechanisms to slow heart rate, reduce blood pressure, and conserve energy.

Quick to shift gears, your body, thanks to these braking mechanisms, is equally quick to reequilibrate.

Cannon recognized that such a coordinated response to disruptive events could not occur in a large multicellular organism without the rapid dissemination of information. That this communication must involve the exchange of chemical signals was also apparent. Adrenaline, for example, was clearly responsible for the changes in circulatory function, muscle tone, sweating and shivering, and mental alertness that constituted the response to emotional excitement; deprived of its call for action by disease or experimental manipulation, the slightest stress sent the body into a tailspin. But in Cannon’s time, only a few such signals had actually been identified and isolated. As for “what influences the signal and how the signal sends orders to the organs that make the correction,” that, Cannon admitted, “must remain a mystery until further physiological research has disclosed the facts.”

Research has taken the mystery out of the discussions that maintain homeostasis. In the signaling pathways responsible for such mundane functions as the upkeep of tissues and the disposition of nutrients, scientists have not only discovered how “the unstable stuff of which we are composed … learned the trick of maintaining stability” but also how an accumulation of petty misunderstandings can throw the body off balance, how a misstep here, a stumble there, can escalate until there’s no turning back from a freefall into disaster.

FLESH AND BLOOD

I don’t remember why I went back upstairs, but it’s a damn good thing I did. The new claw-foot bathtub, which should have been draining into the outflow pipe, was instead draining all over the painstakingly selected color-coordinated ceramic tile floor, the result of a hairline crack in its base. Manufacturing defect? A sudden stop of the delivery truck? One too many turns of the wrench during

installation? Months later, I’m no closer to an answer, a refund, a new plumber, or an operative bathtub.

Just add it to the list.

The walls were painted only a few weeks before the bathtub was installed, and they already need a touch-up. The bathroom window frame—along with the six others in the upstairs bedrooms—has warped so badly that wedging a screen into it has become a Herculean task. My rocking chair is about to collapse. Another slat is loose on the deck railing, the freezer in the basement just went haywire, and the washing machine makes an ominous clunk during the spin cycle. It’s enough to make you dread Saturdays and wonder if mortgage approval ought to be contingent on opening a direct deposit account at the Home Depot.

Maintaining the infrastructure is an ongoing concern for the body as well as the home owner. Accidents can and do happen, even to the most careful. Skin cells rub off on clothes, wash away in the shower. The lining of the stomach needs a steady stream of new cells to replace those corroded by acid, seared by spicy food, mutilated by powerful enzymes. A red blood cell’s days are numbered—at about 120 to be exact—from the moment it reaches maturity. Injuries must be repaired and casualties replaced, or the body will deteriorate as steadily as an aging house.

During development, when the embryo was just a mosaic of equivalence groups, replacing cells lost through accident or injury was easy—survivors simply divided to bring the number back up to normal. In the adult, home repair is the province of experts. Some jobs are carried out by cells with good memories, able to recall and repeat words they learned during development: the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels, liver hepatocytes, fibroblasts. Others may have retired their cell-cycle machinery, but these journeymen, fed the right combination of growth factors or embryonic signals, can still duplicate their DNA and divide to yield two identical daughters. And for everything else, there are stem cells.

Forget botox. The profligates that biologists call stem cells have their own secret for staying young: run away and hide in a place far from the machinations of transcription factors with an eye on your genes. While most cells were finalizing their career choices, therefore, stem-cells-to-be gave up on growing up and stole off to secluded environments, or niches, deep inside nascent organs, where they could postpone differentiation indefinitely. There, they will be permitted to divide all life long. But in contrast to drudges like fibroblasts, the progeny of stem cells are not always identical twins. On average, about half the daughters of stem cells leave the niche and complete the task their mothers abandoned, differentiating into replacements for cells lost by mature tissues. The others stay behind and become stem cells themselves, so that the number of cells in the niche remains constant. The closest we’ll ever come to being immortal, this little bit of the embryo in the adult body is a self-perpetuating, inexhaustible resource, ready to be tapped whenever accident or attrition creates a need for new cells.

The skin is an example of a tissue that could keep a contractor employed seven days a week. Shielding the lower layer, or dermis, is a roof, the epidermis, shingled with stacks of interlocking keratinocytes (named for the cords of keratin protein stacked end to end inside of them) and in constant need of repair. For starters it’s always losing shingles. The “cells” nearest the surface are actually ghosts; dead keratinocytes shed in prodigious numbers every day. To replace them, the epidermis relies on a cache of stem cells stored near the epidermal-dermal border. Like machine parts loaded onto a conveyor belt, cells continuously exit this so-called basal layer, rise toward the skin surface, mature into full-fledged keratinocytes, and finally die, their internal organelles crowded out by keratin filaments, their future reduced to an afterlife as house dust.

As if planned obsolescence wasn’t trouble enough, the skin, our largest organ, is also one of the most vulnerable, enduring “more direct, frequent, and damaging encounters with the external world

than any other tissue in the body.” Assailed by wind, weather, ultraviolet light, and the occasional sharp object, the skin must marshal stem cells in the epidermis as well as fibroblasts and endothelial cells in the dermis to repair the damage. For these jobs—complicated, with several kinds of cells to engage and direct—the skin needs to be a more articulate conversationalist. Reaching into the past, it must recall words that will fire up the cell cycle and motivate the dormant; billing and cooing, it must recruit and educate the immature.

Conditions at the site of a freshly inflicted wound are no different from those at any accident scene—hectic, theatrical, and noisy, a pandemonium of cries for help, police and paramedics barking orders, onlookers offering help and comforting the injured. Once the damage is contained, however, the reconstruction team is ready to go to work, led by blood cells—actually fragments of larger cells—known as platelets. “You there!” they shout at fibroblasts in the nearby dermis. “Platelet-derived growth factor!” The fibroblast crew snaps to attention, begins dividing, and dives into the wound bed to hammer down floorboards of collagen, the foundation of the tough scar that will replace the spongy blood clot. “Good job,” say the platelets. “You’ve earned a promotion.” Now the fibroblasts can issue orders of their own: the fibroblast growth factors FGF2 and FGF7. Then they’re promoted again, to myofibroblasts, lectured by platelet-derived growth factor until they are tough enough to contract and pull the edges of the wound together.

Meanwhile, in the basal layer of the epidermis, epidermal growth factor (EGF) and TGF-β (the patriarch of the family that includes bone morphogenetic proteins) talk to the keratinocytes and their progenitors. EGF gives motivational talks to the stem cells, encouraging them to divide. Assisted by FGF, it also orders the new keratinocytes to slide sideways and raise a roof over the wound. TGF-β gives keratinocytes the green light to call in the plumbers. I can’t find someone to reconnect a bathtub, but with a single word—“vas-

cular endothelial growth factor,” or “VEGF”—the cells rebuilding the skin can command the installation of an entire network of new capillaries.

Generating the blood destined to flow in these vessels is a more complicated project than building skin, however. Blood contains at least 10 different kinds of cells: erythrocytes, the red blood cells that ferry oxygen; three types of phagocytes, white blood cells eager to devour bacteria and scavenge the corpses of fallen cells; B cells that secrete antibodies and T cells that kill damaged or infected cells and nurture B cells; natural killer cells; platelets and the megakaryocytes that spawn them. All are born in the bones, and all are the handiwork of a single cadre of uniquely versatile stem cells.

Their queen arrived without fanfare, hidden under the bark of an ornamental shrub. Instead of accepting a crown, she marked the beginning of her reign by breaking off her wings. Now she lives to lay eggs and will never again see the light of day.

The walls of their very ordinary suburban house, my neighbors learn, have become home to a great dynasty: blind workers, fierce soldiers with huge snapping jaws, pale nymphs on the threshold of adulthood, and at the dark, cool heart of the nest, the queen of this Empire of Termites, reclining in her brood chamber.

The human skeleton is home to another occult kingdom ruled by a caste of immigrant queens. While the bone matrix slowly turned to stone, its substratum of spongy connective tissue, the marrow, remained red, warm, and alive. Earlier in development, hematopoietic (“blood-making”) stem cells, born in so-called blood islands—clumps of mesoderm orbiting the yolk sac—poked around the primordial aorta, visited the nascent liver. Now they are ready to come home. Tired of foreigners and suffused with archetypal memories of a faraway palace waiting for them in the bones, they ride the bloodstream to humerus and femur, pelvis and sternum, crawl out of the bone capillaries, and settle in the marrow. Now, like the ter-

mite queen in her timbered hall, these hematopoietic stem cells recline on their cushions, breeding blood cells as inexorably as she lays eggs.

Hematopoietic stem cells never entirely give up their wandering ways. Even in adults, “at any given time, a few—in a mouse, maybe a hundred cells—can be found in the circulatory system,” says Amy Wagers, a stem cell researcher at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston. But the overwhelming majority, she emphasizes, stay in the bone marrow. If they left, they’d have to grow up. “Hematopoietic stem cells need the niche to stay stem cells,” says Wagers. “If a daughter cell loses contact with niche cells, it goes on to differentiate.”

And what are the words to this spell that confers eternal youth and an infinite capacity for self-renewal? The bone marrow cells kept the secret for a long time, but scientists have finally pieced together a few of the words—and discovered that the best way to talk to infants, even infantile cells, is in baby talk. Some of the same signals that controlled cellular fate and drove cell division in the embryo can be found in the mature organism cooing at stem cells. Wnt, for example, can keep even hematopoietic stem cells transferred from their precious niche to a culture dish dividing and replenishing. Notch is another synonym for “stay young”; Sonic hedgehog is a third.

In times of crisis, these signals can turn up the volume, sending cell division into hyperdrive. At peak capacity the hematopoietic stem cell population may increase by as much as tenfold. “Mobilization is an evolutionarily conserved process and probably originated as a response to catastrophic blood loss,” suggests Wagers. Legions of new stem cells rush out of the bone marrow, migrate to the periphery, and colonize sites in the liver and spleen. From these migrants, “you can expand the entire blood cell tree,” Wagers notes, adding that as few as five stem cells are enough to reconstitute the hematopoietic system: erythrocytes, phagocytes, granulocytes, T and B lymphocytes, and platelets.

Bearing life-giving oxygen and fighting off enemies are both honorable professions; still the daughters of blood stem cells relinquish their immature obsession with dividing and their antipathy to commitment slowly and cautiously. You can’t help but sympathize—to take that first step, altering their gene expression pattern just enough to become a so-called lineage-restricted stem cell, they must give up both their limitless potential and their immortality. They can still divide, and their identity is still a work in progress. But some have committed to the myeloid path, which will train them to become red blood cells, platelets, or phagocytes and others to the lymphoid path, where they will prepare for careers as B cells or T lymphocytes—both irrevocable decisions—and all will die, most within six to eight weeks of that fateful choice.

Each step on the path to maturity entails another sacrifice. The daughter of a lymphoid progenitor must commit to either the B cell or the T cell lineage; the daughter of a myeloid progenitor may continue down the path marked “red blood cells” or the one marked “macrophage,” or one of the granulocyte pathways, but she may not cross paths or change directions. Progeny of these committed lineage-restricted stem cells relinquish the last of their stem cell privileges: the right to divide. Resigned to their fate, they can do no more than refine their gene expression pattern to complete the task of preparing for their chosen jobs.

Such weighty decisions for infant cells, so unreasonable to expect them to muddle through on their own. Fortunately, they have a school right on the palace grounds. Cavities and alleyways serve as classrooms, and instructional materials are provided by the stromal cells in the bone marrow, the endothelial cells of capillaries, or mature blood cells. Cells that graduate earn the right to a job in the blood, with a guarantee of lifetime employment.

Classes here at Marrow High are taught in “Cytokine,” a dialect related to Hormone. In fact, you can think of cytokines as minihormones, made and secreted by small clusters of cells rather

than endocrine glands. Like adrenaline, estrogen and progesterone, thyroid hormone, and insulin, cytokines are words meant for discussions with colleagues who don’t live next door, but while endocrine hormones travel far and wide in the bloodstream, most cytokines have a shorter range of influence; they are a middistance medium.

Like growth factor receptors, cytokine receptors relay signals through tyrosine kinases; like G protein–coupled receptors, this kinase transducer is a separate protein. Known as “Janus kinases,” after the two-faced Roman god, or JAKs, these transducer kinases respond to the binding of cytokine by phosphorylating themselves and then the receptors. The receptors then phosphorylate an SH2-interaction domain-containing transcription factor of the STAT (for signal transducers and activators of transcription) family. Finally, two STATs pair off to form a single gene regulatory complex that carries the message into the nucleus.

Here’s the curriculum for a developing red blood cell. A freshman precursor cell of the myeloid (red blood cell/macrophage) lineage signs up for the introductory course “Commitment 101.” Required reading: the cytokines stem cell factor (known colloquially as “Steel”), interleukin-3, and interleukin-9. A passing grade entitles a graduate of this class to call itself an “erythroid precursor cell,” automatically registered for next term’s “Introduction to the Erythrocyte Lineage,” where it will delve deeper into the meaning of interleukin-3 and Steel. After that, cells take a sequence of laboratory courses. In “Responding to Hypoxia I and II,” they will hear lectures by one of the few cytokines adventurous enough to brave a trip through the bloodstream: erythropoietin, produced and secreted by the kidney. When they’re done, red blood cell aspirants will know how sensors in the kidney monitor blood oxygen, how a crisis that causes oxygen levels to fall—a move to the mountains, blood loss from a massive injury—prompts the kidney to release erythropoietin, and how they should respond to that alarm. To round out their education, students will complete an internship in which they’ll prac-

tice the preparation and use of hemoglobin and a final exam in which they’ll be asked to jettison their nuclei and pack themselves with the hemoglobin they’ve made. Cells that complete the entire course of study will be awarded a “Master of Oxygen Transport” degree, entitling them to begin their 120-day stint as cellular oxygen tanks.

We chose plastic laminate when we replaced the kitchen floor because it looks like wood but is easier to repair. And when someone does drop a kitchen knife or break a glass, we’re prepared—we have six boxes of the stuff stored in the garage. When we get around to repainting that bathroom, we have three cans of paint (wall and trim colors) as well as drop cloths, drip pans, brushes, and rollers. Extra wallboard? We’ve got that, too, stacked behind the flooring. The old curtain rods? Wouldn’t dream of throwing them out. We’ve even bought replacements for those old windows—and enough to replace the windows downstairs, too. In fact, we’ve accumulated so many building materials in the course of remodeling it’s hard to tell if that structure on the side of the house is a garage or a lumber yard.

Apoptosis is the body’s alternative to a yard sale. On a day-to-day basis, it regulates the number of stem cells and their progeny so that the number of cells born never outstrips the number lost. Even in times of crisis, when stem cell reservoirs are churning out replacements to repair some catastrophe, it maintains homeostasis and prevents unnecessary clutter. Finally, suicide offers cells a way to atone for any errors made during the course of cell division—an important safeguard when continuous transit through the cell cycle is a way of life.

Silence and isolation can convince any cell it’s better off dead, and stem cells are no exception. For example, hematopoietic stem cells cultured without the benefit of stem cell self-renewal signals such as Wnt quickly lose their will to live. The proapoptotic and antiapoptotic factors contesting the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane may also play a significant role in stem cell apoptosis.

Increasing levels of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 can give hematopoietic stem cells a new lease on life, and these survivors are more vigorous as well, replenishing irradiated bone marrow even more effectively than the stem cells of normal mice.

Development does not end when we are born. No matter how long we live, the cells set aside to repair body tissues will never grow up, never stop dividing. Conversely, part of us is always dying. Apoptosis sweeps away the superfluous, preserving the balance calculated over millions of years of evolution.

Notions of expansion are unacceptable to a society ruled by homeostasis. The community of cells that constitute the adult body is a closed society and “has no provision for any process which would be the equivalent of immigration. Nor has it any provision for unlimited growth, either as a whole or in its parts,” writes Walter Cannon.

“Indeed, when some cells reproduce themselves in an uncontrolled manner they form a malignant disease, endangering the welfare of the organism as a whole. Against such pathology,” he concludes, “the body has no protection.”

BAD, MAD, OR OUT OF CONTROL?

Question: What do a one-eyed lamb and some cancer patients have in common? Answer: Both have abnormalities in Hedgehog signaling to thank for their problems.

Fresh greens, cool mountain air, and the freedom to wander at will—what could be healthier for a mother-to-be? Sheep ranchers know, however, that in the Rocky Mountain meadows, danger can be as close as the next bite. Veratrum californicum, commonly known as the corn lily, grows here, and pregnant ewes that nibble on its broad leaves early in their pregnancies give birth to lambs with mis-shapen faces and a single monstrous eye. “Cyclopia,” veterinarians call it.

In the 1950s a Basque shepherd working for a rancher in Idaho

pointed out the corn lily plant to agents from the U.S. Department of Agriculture seeking a reason for a sudden surge in the incidence of cyclopia. It made pregnant sheep sick, he told them. In controlled trials, USDA scientists showed that ewes deliberately fed corn lily leaves gave birth to cyclopic lambs. From the plant’s tissues they isolated a cholesterol-like compound responsible for its disastrous effects on the developing fetus and called it, appropriately enough, “cyclopamine.”

Cyclopamine caught Philip Beachy’s attention because he’d learned that mice lacking the signaling protein Sonic hedgehog were also born with cyclopia. Beachy reasoned that cyclopamine might be interfering with Hedgehog sentences; based on its chemical structure, he thought at first it might be disrupting the synthesis of the all-important cholesterol tail. “Then we learned that it interfered with signaling, not processing,” he says. “It blocks cells’ ability to respond to Hedgehog, and its target is Smoothened. In animals treated with cyclopamine, the Hedgehog pathway is constantly suppressed, even if Sonic hedgehog is present, because the drug disconnects Smoothened from the transcription factor complex.”

Gorlin’s syndrome, also called basal cell nevus syndrome, causes a constellation of birth defects that are the mirror image of cyclopia. Instead of a single eye, patients with this heritable condition have abnormally wide-set eyes and a broad, flat nose. But the most disturbing feature of Gorlin’s syndrome is not how patients look but how easily they develop cancer. A diagnosis of Gorlin’s syndrome is nearly synonymous with a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma, the most common form of skin cancer. Nearly all patients eventually develop skin cancer—unless they succumb first as children to the brain cancer medulloblastoma.

Cyclopamine silences Hedgehog signaling. In Gorlin’s syndrome the Hedgehog signaling pathway is never quiet. “These patients turn out to be heterozygous for Patched,” says Beachy (that is, one copy of the two copies of the gene is defective; the other, inherited from

the other parent, is normal). Every patient eventually gets basal cell carcinoma when a second mutation in the remaining Patched allele results in a total loss of function.” Without a functioning Patched receptor, Beachy explains, “Smoothened fires constitutively. The pathway is full-on, even in the absence of Sonic hedgehog, because there’s no repressor.”

Some cells just seem to be looking for trouble. Basal cell carcinomas originate in the basal layer of epidermis that includes skin stem cells and their immediate progeny, still immature and capable of dividing. Tissues like these, home to noteworthy populations of stem cells, constantly in need of repair, and among those most likely to encounter carcinogens—chemicals, ultraviolet light—are an accident waiting to happen, poised on a knife-edge between normal repair processes and pathological overgrowth. “Stem cells already look a lot like tumor cells,” Beachy says. “They already have the capacity for growth. It’s just restricted to a particular niche.” A little misunderstanding, an incendiary word, a heritable case of logorrhea and cells like these may escape the homeostatic constraints that ordinarily temper cell division, a failure that can quickly endanger the welfare of the entire organism.

Eyes see, brains think, and lungs breathe. Skin protects; bones support. Cancers grow. Reckless proliferation is cancer’s trademark, encroachment its principal weapon in a battle with the body. As cancer researchers Gerard Evan and Douglas Green put it in 2002, “Much of the characteristic pathology of cancer arises spontaneously as a consequence of interactions between the expanding mass and its somatic milieu.” Cancer’s growth spree often begins with a media takeover: subversion of the signaling pathways that regulate proliferation and embryonic development. The architects of this rebellion are perverted versions of cellular signaling proteins, receptors and kinases that have had an amino acid or two deleted, added, or swapped in a genetic accident, so they no longer mean quite the same thing they did before the mishap.

Mutation is the price organisms pay for a long life in a perilous and imperfect world. Spontaneous chemical reactions, reactive forms of oxygen, ultraviolet light from the sun, and environmental toxins assail the DNA. Retroviruses leave their genetic garbage in the genome. Every time a cell divides, whether it’s to build a limb, maintain the blood supply, or heal a wound, a gene can be miscopied or duplicated. Pieces of chromosomes can trade places, separating genes from regulatory sequences. Fortunately, innate surveillance and repair mechanisms spot and correct most mistakes before they spawn deviant proteins. Should a mutation slip past unnoticed, however, the corrupted gene will give rise to a corrupted protein.

Genetically reengineered proteins can disrupt conversations related to proliferation—and trigger a cancer—in two ways. Expansions, deletions, or rearrangements in genes that encode growth factors and developmental signals, their receptors, or components of their intracellular signaling pathways replace normal counterparts with hyperactive imposters that encourage cells to thumb their noses at their neighbors and divide as often as they please. The genes src and fps, encoding the kinases that led to the discovery of interaction domains and adaptor proteins, are examples of such oncogenes, tricksters that cells mistake for legitimate growth signals. Ras, the benign little GTPase we met mediating between growth factor receptors and MAP kinases, is another, mutated in one out of every four human cancers. Mutations in the genes for receptor tyrosine kinases—the epidermal growth factor receptor, the PDGF receptor, FGF receptors—crop up routinely in breast, lung, and ovarian cancers, leukemias and lymphomas, and multiple myeloma.

Other mutations stifle the voice of reason. They knock out so-called tumor suppressor genes, encoding proteins responsible for putting the brakes on cell division. Cells with these mutations hear “go” but never “whoa.” Gorlin’s syndrome illustrates the way a deleted negative can drive cells crazy. Without the Patched receptor to keep Smoothened in check, a Hedgehog sentence always means “yes” even if it no longer begins with Hedgehog.

The pressure to maintain homeostasis is strong, and a single mutation may not be enough on its own to overwhelm the interlocking mechanisms that strive to keep cell numbers constant. But the longer a cell lives, and the more often it divides, the more opportunities it has to accumulate mutations, overriding one control after another until it crosses the line into malignancy. Amy Wagers, referring specifically to hematopoietic stem cells, suggests that longevity is precisely why stem cells may be “hot spots” for tumor initiation: “They are the only cells in the blood that live long enough to accumulate all the hits. Even if you get two or three mutations in progenitor cells, those progenitors are going to die.”

The evolution of colorectal cancer is a well-studied example of how such a succession of small genetic errors can add up to one life-threatening malignancy. The fourth most common type of cancer in the United States, it typically originates in an outgrowth of the gut epithelium known as a polyp. Small polyps are small problems, from a medical point of view, precancerous assemblages of slightly irregular cells easily removed during colonoscopy. But as a polyp grows in size, its constituent cells become increasingly abnormal, antisocial, and aggressive, finally penetrating the intestinal wall as a full-fledged, invasive cancer. Analysis of the genetic makeup of colorectal tumors at various stages of this clinical progression, carried out by Bert Vogelstein, Ken Kinzler, and colleagues at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, have demonstrated that the progression from polyp to cancer is accompanied by a sequential accumulation of mutations, beginning, in many cases, with the derangement of a critical signaling mechanism—the pathway headed by the embryonic mitogen and morphogen Wnt. Mutations in the gene encoding the protein APC (for adenomatous polyposis coli, a hereditary cancer syndrome in which patients develop hundreds or even thousands of polyps), one of the bullies in the Degradation Complex that attacks the β-catenin protein to keep it out of the nucleus, occur in more than 70 percent of colorectal cancers; look closely and you may find them lurking in even the smallest and least malevolent of

polyps. With APC disabled, the rest of the gang disperses. A steady stream of intact active β-catenin molecules chant “go, go” at genes, as if a steady stream of Wnt messages were bombarding the cell. What cells wouldn’t divide manically under such pressure?

But the transformation still isn’t complete. Spurred on by an oncogene, a polyp can balloon into a mob of delinquent cells yet still remain no more than a local disruption. To graduate to a cancer, the cells must acquire not only a mutation that gives them leave to divide with abandon but also a mutation that allows them to flaunt one final social convention: the obligation to die.

They’ll have those expensive Japanese maples you just planted for dinner and enjoy the heirloom tomatoes for dessert. Go ahead and spread blood meal around your annuals—they’ll munch as eagerly as if you’d sprinkled salt on the plants instead of a repellant. No fence, even an electrified one, can stop them. Your car can—but you’ll pay an average of $2,200 to repair the damage.

Welcome to Pennsylvania, home to more white-tailed deer per square mile than any other state on the East Coast.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, deer were so scarce that the Pennsylvania game commission released 1,200 between 1906 and 1925 to appease frustrated sportsmen. Today, 1.5 million deer are devouring woodlands, farm crops, and ornamental plantings to the ground; colliding with 40,000 to 50,000 motor vehicles each year; and providing sustenance to the ticks harboring Lyme disease. The Pennsylvania Audubon Society estimates that in some areas the deer population is nearly four times what the land can actually support. Even urban parks are experiencing a population explosion—in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park, for example, nearly 300 deer crowd into a space big enough for thirty.

The state animal is overrunning the state because most of the natural barriers to overpopulation have failed. Well-fed deer have more babies. With farmers and home owners serving up a veritable feast, it’s no wonder the deer are breeding more like rabbits, with 90

percent of adult does giving birth to twins or even triplets every spring. But at one time even a bumper crop of fawns would have been cut down to size by the forces of nature. Some would have lost out in the competition for food, while many others would have become food, a feast for hungry predators. Now, with food available year-round, wolves and mountain lions decidedly scarce, and hunting curtailed by anxious residents of housing developments that encroach on the forests, the deer have few enemies to keep their numbers within bounds. Once just part of the ecosystem, they are now its greatest enemy, threatening to destroy their native habitat as well as corn crops and landscaping.

“The cancer cell is a renegade,” writes oncologist Robert Weinberg. “Unlike their normal counterparts, cancer cells disregard the needs of the community of cells around them. Cancer cells are only interested in their own proliferative advantage. They are selfish and very unsociable.”

Tony Pawson is more forgiving. Cancer cells are mad, not bad, he says; they act crazy “because they hear voices that fool them into growing. They think they are responding to an external voice, and so they’re behaving inappropriately.” Mutations in growth-regulating mechanisms have cursed them with delusions of grandeur. Oblivious to time-honored social principles like cooperation and self-control, they overrun neighbors they no longer recognize as allies.

But to Gerard Evan of the University of California San Francisco Cancer Center, cancer cells, like the white-tailed deer eating my neighbors out of house and home, are out of control because chance and circumstance have upset the balance of nature. Proliferation is only one side of the equation; after all, Evan points out, “our cells divide by the zillion every day”: during embryonic development, as the egg expands into a multicellular newborn, and in adulthood, to replace the cells we lose in the course of a long, active life. With so many opportunities for cell division to run amok, cancers should be as common as colds.

Yet rebel cells fail along the way to cancer far more often than they succeed.* The reason, Evan argues, is that under normal conditions the human body, like an undisturbed ecosystem, is a self-correcting arrangement. In the forest, a lucky break—a mild winter, a parasite die-off—is usually balanced by inevitable misfortune—a dry summer, a new plant disease. In the body, cell numbers are kept relatively constant by a similar network of checks and balances. If more cells are born, more must die. Only an unusual conjunction of circumstances can tip the balance.

“Replication is an amazing piece of evolutionary conjuring. It’s the easiest thing in the world to proliferate, but it’s quite difficult to proliferate incorrectly,” Evan says.

The magic lies in skilled locksmithing. “How do you make it easy for you to get into your apartment but almost impossible for someone else?” he asks. “You install a combination lock. To open the door, you have a key that flicks all of the pins, in the correct order. You can’t pick the lock by flipping just one pin. You need the key that flips them all.” Similarly, he argues, cells discourage illicit building programs by placing growth under lock and key. The pins of this lock are a network of intermeshing signaling pathways that link cell division and cell survival. Thanks to proteins that cells can use in more than one sentence, signals that order cells to grow also command them to commit suicide. In this ecosystem, apoptosis preys on the exuberant, sweeping through a field of proliferating cells and disposing of the extras like a pack of hungry wolves.

When net growth is permissible—to repair an injury, for example—cells have a key that allows them to “get into the apartment” safely: a unique combination of signals able to activate the growth program while simultaneously blocking the death program. “The two together give you something you don’t have singly,” says Evan.

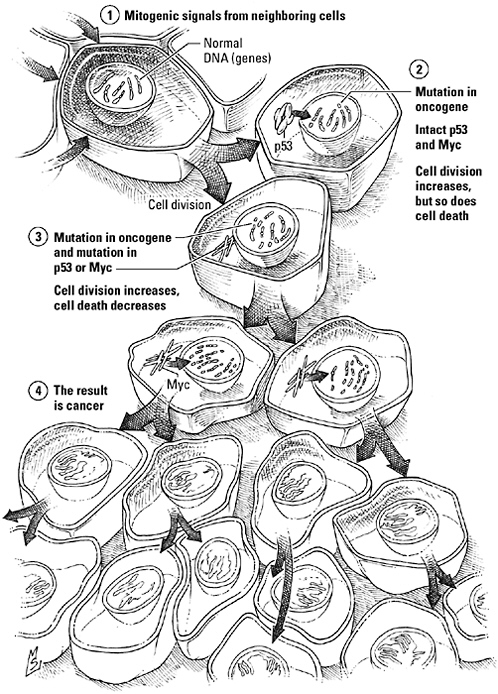

Coupling proliferation to apoptosis was a master stroke for preserving population homeostasis, a way to underwrite the upkeep on a relentlessly eroding body while minimizing the risk of cancer. As long as birth and death remain tightly linked, even a mutation in an oncogene cannot ignite a population explosion because cells die almost as quickly as they divide. But if cells also lose their will to die, the stage is set for an ecological disaster. A mutation that promotes growth and a mutation that prevents death—that’s the “minimal platform” on which all cancers are built, Evan concludes.

“Cancer cells, by and large, don’t do anything normal cells wouldn’t do following injury or during development,” he says. “What’s different is how they regulate—or don’t regulate—that behavior. They have mutations that make them live out of control.”

For centuries, religious law banned suicides from church graveyards; civil law called for their corpses to be dragged through the streets, hanged, or burned. But even the most orthodox wavered when an individual chose to die in defense of the faith, the crown, or another human being. As one sixteenth century writer observed, “If it were not permitted to expose our lives for the lives of others, the physician could not exercise his art in time of plague, nor could the wife brave the danger of contagion to care for her husband stricken by the plague, nor could a shipwrecked man cede to another the plank that is his salvation.” The altruistic deaths of heroes and martyrs argued that choosing to die could be a noble sacrifice as well as a grievous sin, that while a man could kill himself out of wickedness, madness, or despondency, in an act of unbelievable devotion, he could also “lay down his life for his friends.”

A cell with a damaged genome has an obligation to lay down its life before it becomes the ultimate biological weapon. Like the sacrificial deaths of saints and heroes, such suicides are acts of altruism, undertaken to safeguard the health and well-being of the body as a whole. But should a troubled cell begin to entertain the idea of sedi-

The “cancer platform.” Mutations in oncogenes stimulate abnormal proliferation but are not by themselves sufficient to cause cancer because interlocking signaling mechanisms that oversee cell growth and voluntary cell death, or apoptosis, ensure that any signal triggering an increase in growth will trigger an increase in cell suicide as well. A mutation that uncouples these processes or blocks apoptosis, however, eliminates this natural brake on uncontrolled growth and opens the door to a full-fledged malignancy.

tion instead of suicide, a counselor is on call at all times, ready to remind it of its sworn duty to protect the community at large. Named “p53” (for its molecular mass), healthy cells are barely aware of its existence, for most of the p53 protein a cell makes is marked for the garbage disposal almost as soon as it’s off the ribosome. When a damaged cell is detained at a cell cycle checkpoint, however, p53 is phosphorylated and stabilized. Now this thanatologist can either shut down the replication machinery or select a go-between (the proapoptotic thug Bax is one of its favorites) to remind the cell of its civic duty to die.

If a mutant cell should slip past the sentinels, the body can still depend on oncogenes. Oncogenes? The corrupted proteins that may have caused that cell to go haywire in the first place? That’s right—because many oncogenes are also “apogenes,” telling cells to grow one minute and to kill themselves the next. “When you pick up the proliferation program, you pick up the death program as well,” Gerard Evan explains.

The most notorious two-faced double-dealer of all is the transcription factor biologists call “Myc,” activated when growth factor sentences take a 90 degree turn at the level of Ras, opting for the clause with the second messenger PIP3 as its direct object. A real workaholic, Myc oversees the expression of nearly 10 percent of our genes, from metabolic enzymes to structural proteins, from proteins needed to copy DNA to the proteins operating the cell cycle. In its active form, therefore, Myc can fiddle with switches, pull out plugs, and reprogram machinery all over the cell. For example, at the same time it’s cranking up cell division, Myc is also turning in the dividing cells to the police. “Just trying to help,” it insists, as it adjusts a cell’s hearing—the better to hear signals of stress and injury certain to trigger suicidal ideation. “How about some air in here?” it chirps, as it opens windows in the mitochondrion, releasing deadly cytochrome c. Perhaps it would caution cells not to run with scissors, but these scissors are caspases, and they cut so beautifully.

“Myc has these two contradictory properties—it drives cell proliferation and it drives cell death. And that seems counterintuitive,” notes Evan, “until you compare it to putting the brake on when you start your car. Before you shift into drive, you first need to protect against accidents. You take a second look to see if it’s safe to proceed before you actually go anywhere.” Similarly, he continues, Myc reminds the cell to “stop, look, and listen” before it dives headfirst into proliferating. “Myc equips the cell with the wherewithal to expand and remodel and, at the same time, with all it needs to abort if necessary.”

Mutations in Myc are tantamount to brake failure. A cell with a mutated oncogene is already in a big hurry to divide. Without Myc to insist on caution, it shoots out of the driveway and peels away full-speed toward disaster, running over nearby cells unable to get out of its path.

Apogenes and altruism are for conformists. A cancer cell obeys no social conventions, accepts no limits, acknowledges no authority. Bad, mad, and out of control, even a direct command to commit suicide may no longer contain its pathological rebelliousness.

My husband pounced on the box of books at a yard sale, paid five dollars for the lot, and dragged them home. “I had these as a kid. We bought them in the grocery store,” he mused as he took them out one by one and read their titles: “Mathematics. The Insects. The Universe. The Planets.”

“Hey, give that here,” I interrupted, recognizing his find immediately as a nearly complete collection of the Time-Life Nature and Science Library. “I remember these. They were one of the things that got me interested in science.”

Vishva Dixit grew up in a rural village in Kenya, far from a grocery store, but he too was attracted to science by the Time-Life Nature and Science Library. “I can’t imagine it now,” says Dixit, now a senior researcher with the South San Francisco drug company

Genentech, “but we used to get these Time-Life science books, called things like The Insects or The Planets, 10 miles from the equator, in an African village. I looked at them, and I don’t know if it was a curse or an enlightenment, but that just captivated me. I said, ‘This is what I want to be.’”

Dixit’s parents wanted him to be a doctor—a “profession that guaranteed security”—not a scientist. He completed medical school in Kenya, then chose “an enlightened research-oriented program” at Washington University in St. Louis for his residency. Six years later, Dr. Dixit had his own laboratory, as well as his medical degree, and he’d just discovered a problem he couldn’t wait to investigate.

“I ran into an article in Scientific American on tumor necrosis factor, this protein that could literally make tumors melt away,” he recalls. “And it struck me that here was a substance that you just sprinkled on cells and, lo and behold, they died, while you observed them, in a matter of hours. They were as dead as doorknobs. There was nothing complex. This wasn’t a mouse you had to manipulate or a dissection you had to do. The question was ‘What happened?’”

Tumor necrosis factor, Dixit had learned, was a subtle chemical weapon. It didn’t simply injure or poison cancer cells. It ordered them to kill themselves.

The decision to die is not one that cells take lightly. They would prefer to wait for an explicit command, from p53, say, or from a signal like tumor necrosis factor, one of a family of signaling proteins that apoptosis researchers call “death ligands.” When Dixit began his quest to learn how tumor necrosis factor persuaded cells to kill themselves, the scientific community knew that this death ligand, like other signaling molecules, transmitted its sinister message to its victims by way of specific receptors that spanned the cell membrane. They even knew the DNA sequence of the tumor necrosis factor receptor. What no one could figure out, however, was what happened after signal and receptor connected.

“Much to our chagrin, there was nothing in their [the receptors’] sequence that suggested a signaling mechanism. They weren’t linked

to a G protein. They weren’t kinases. How in blazes were they signaling?” says Dixit.

Then scientists studying apoptosis in the development of C. elegans discovered the ced-3 protease—and that a mammalian enzyme used in the production of certain cytokines, interleukin-1β-converting enzyme, or “ICE,” closely resembled the worm protein. They speculated that an ICE-like protease might be the elusive death effector, a hypothesis that led to the discovery of the first caspase. In addition, Dixit learned that the receptors for death ligands were molecular arms dealers. Like the adaptor proteins of receptor tyrosine kinase pathways, death receptors contain an interaction domain, the “death domain,” that enables them to recruit a band of confederates—other adaptor and scaffolding proteins—and link them to form a chain that allows them to access the killer caspases.

“In the end, it was a very simple model,” Dixit observes. “What I liked about it was the elegance of its simplicity. It was very chaotic when we began to work on it, a morass of confusion. Yet when the smoke clears, you are left with this work of art.”

Actually, recent evidence suggests that tumor necrosis factor signaling is not quite as simple as it first seemed. Just as Myc can promote cell division or call for cell death, this death ligand, it turns out, can also be a life ligand. In fact, the initial reaction of the adaptor that’s first to join up with an activated tumor necrosis factor receptor, known as “TRADD,” is not to look for a caspase but to call for a kinase that forwards news of ligand binding to the transcription factor NF-κB, an overseer of proliferation genes. The activation of NF-κB then rouses antiapoptotic factors that promote cell survival rather than cell death.

Thoughts of suicide don’t surface until this “complex I” breaks up, freeing TRADD and the kinase to drift into the interior of the cell in search of new partners. Now another death domain–containing protein, FADD (for Fas activated death domain, Fas being another of the death ligands), makes an appealing sidekick. FADD already has connections to a signaling caspase; together with recep-

tor-activated TRADD, the three form a second signaling complex, complex II, able to activate a killer caspase and trigger apoptosis.

In other words, the tumor necrosis factor receptor, more like Myc than one of the proapoptotic thugs that punch holes in mitochondria, is a checkpoint where cells can weigh the decision to live or die. If signaling through complex I and NF-κB wins out, the cell will survive. If the voice of complex II drowns out the proliferation option, death by suicide is the decision. But one little mutation is all it takes to override the voice of reason. Addle the tumor necrosis factor receptor or one of the adaptor proteins and apoptosis drops off the list of options. Now the terms “death ligand” and “death receptor” have new meanings. Without the brake of suicide, cells can plunge into a frenzy of malignant proliferation; worse, the activation of NF-κB allows cancer cells to resist chemotherapy, compromising treatment. Such mutations have been identified in breast and lymphoid cancers and have been shown to promote tumor growth and metastasis.

Cancer cells have even more devious ways of compromising signaling by death ligands. Some lung and colon cancers, for example, lie to receptors to circumvent the death ligand FasL, elaborated by white blood cells patrolling for such miscreants. Under ordinary circumstances, the binding of FasL and the Fas receptor spells certain death. In one study of 35 lung and colon tumors, however, about half had discovered how to make an inactive soluble form of the Fas receptor. This “decoy receptor” bound and sequestered FasL, shielding the tumors from its lethal effects.

Death ligand signaling, “is, of course, an irreversible mode of signaling,” Vishva Dixit concludes. “Then again, death is an irreversible event.” But by virtue of mutations that allow them to ignore irrevocable calls for suicide, seditious cancer cells can escape the finality of death, or at least postpone it until their irresponsible behavior destroys their habitat.

We all want to live as long as possible; forever sounds good to many. But as cancer researchers like Gerard Evan can tell you, immortal-

ity—on the cellular level at least—is incompatible with life. A refusal to die is an invitation to cancer—a triumph for the malignant cell, a loss for the forces of homeostasis, and a disaster for the body.

EATING TO LIVE, LIVING TO EAT

I meant to eat breakfast. But then I cut my finger with the new bread knife, the phone rang, the bagel burned, I spent 20 minutes looking for the checkbook so I could get the credit card bill in the morning’s mail, the phone rang, I remembered that I needed to reschedule the orthodontist because Haley needed to stay after school to make up an algebra test, the dogs wanted to go out, and the phone rang again.

I settled for a second cup of coffee.

And I meant to eat lunch—I even grabbed a package of strawberry Pop Tarts on the way out the door, en route to my riding lesson. I looked forward to snacking on them during the drive home. Then my cell phone rang. I should have pulled over, but I was running late, so I sacrificed eating in favor of keeping one hand on the wheel. Then I had to negotiate a road under repair and a couple of bad drivers. By the time I arrived at the school to pick up Haley, I’d forgotten all about food.

“How can you eat these things?” she demanded, holding my Pop Tarts at arm’s length. I did have to admit they were a little worse for the wear after an afternoon on the front seat of a warm car.

“Hey, that’s my lunch.”

“You should eat a real lunch already.”

“If they’re so awful, why are you eating them?”

“I need to replace lost energy. I had swimming and an algebra test today.”

We finally split the Pop Tarts. Then we picked up poster board for Haley’s science project, dropped off the videos, and replenished the milk supply. We drove back to the barn so that Haley could commune with her pony and picked Jenny up from work. I gave a short lesson in factoring polynomials, solved the crisis of two collies

and a library book, did a load of laundry, found a missing pair of eyeglasses, abused a couple of telemarketers, and recited the many reasons why we could not buy a third horse. I wanted chicken, but that would have caused another crisis, so I agreed to spaghetti and meatballs and finally sat down to dinner—my first real meal of the day. (My husband was in Boston that night. He had dinner at the Ritz Carlton.)

It isn’t easy balancing the needs of two careers, three other people, and four animals with those of one mother. And it isn’t easy for my body, either, balancing a 16 hour-a-day demand for energy with my unorthodox eating habits. Yet despite my best efforts to destabilize my internal milieu, my blood glucose levels have remained high enough to keep me from fainting and low enough to keep my doctor happy. More impressively, my body has juggled supply and demand well enough over the long term that I can still wear the Armani jacket I bought before I had children and began to live on Pop Tarts and pasta.

Six months ago, Joe never thought much about what he ate or when he ate it either. He was one of those people who are “never hungry” in the morning. He was usually “too busy” for lunch. “Really, the only meal I ate every day was dinner,” he says. “That and maybe a bowl of ice cream with my wife later while we watched television.” But that was before a blood sugar reading over 1,000—10 times the acceptable level for a healthy person—landed Joe in the intensive care unit of the local hospital for a week. Now he juggles portion sizes, food selection, medication, and exercise and worries if eating a piece of fruit will give him enough energy to make it through to lunch or add too many calories, if taking a walk will keep his blood sugar within acceptable limits or send it plummeting too far in the opposite direction.

Diabetes sneaks up on people that way. “I should have seen it coming. I had all the symptoms,” Joe recalls. “I was thirsty all the time. Of course, if I drank more that meant I went to the bathroom

more often. And my eyes. I couldn’t understand why my vision was getting worse and worse, even though my eye doctor had just changed my prescription again. For God’s sake, my dad even died of diabetes. And I still didn’t realize it until it was almost too late.”

Steeped in fluid, the cells of the body drift in blissful isolation far from the chaos of the outside world. For Walter Cannon the constancy of this fluid matrix was the key to a “free and independent life,” the shield behind which cells could devote themselves to their specialized functions without risking starvation, dehydration, or exposure. “Insofar as the constancy of the fluid matrix is evenly controlled,” Cannon noted, “it is not only a means of liberating the organism as a whole from both internal and external limitations, but it is an important measure of economy, greatly minimizing the need for separate governing agencies in the various organs.”

Keeping cells well fed is one of the most important duties of the homeostatic mechanisms regulating the composition of the fluid matrix. Mammals, supporting large brains as greedy as a gas-guzzling SUV, must satisfy a relentless demand for fuel. If they were barnacles, flooded with dinner options on every incoming wave, meeting that demand would be as simple as waiting for the sea to wash over them. But they must take their meals when and where they can, and glucose availability rises and falls accordingly. Yet while a hearty dinner staves off one sort of crisis, it creates another, for the glucose that sustains cells can also poison them. High concentrations of glucose trigger fluid retention, ischaemia, and the release of vascular permeability factors, events that are especially destructive to the delicate capillaries supplying the retina, kidney, and peripheral nerves. To be on the safe side, any glucose the body cannot use immediately should be discarded before it causes trouble—but that would be wasteful in light of the effort invested to obtain that fuel. Regulatory mechanisms must find a middle ground. Too little glucose and active cells will not have enough fuel to meet their energy

needs. Too much and the body risks irreparable destruction to the vasculature, resulting in blindness, crippling neuropathy, or renal failure.

Communication is the basis of a sound energy policy, emphasizing a balance between starving cells and killing them with kindness, tempering the after-dinner surge in blood glucose and wasting most of a hard-won meal. A central element of this policy is the dialogue between body tissues and the endocrine gland known as the pancreas, mediated by the hormone insulin. Released in response to rising blood glucose levels (for example, immediately following a meal), insulin titrates the concentration of glucose by suspending the mobilization of glucose reserves and commanding muscle, liver, and fat cells to clear the excess and store it as glycogen or fatty acids. “Waste not, want not,” it pontificates, proud that an imminent threat has been transformed into a resource the body can draw on to keep cells in times of scarcity.

For the 18 million Americans like Joe who suffer from diabetes (specifically, type 2 diabetes, the form of the disorder responsible for 90 to 95 percent of cases), this dialogue has broken down. The most prevalent metabolic disease in the world, type 2 diabetes increases the risk of heart attack and stroke two- to fourfold, accounts for 24,000 new cases of blindness each year, and is the most frequent cause of kidney failure and nontraumatic limb amputation. When you add up the costs of treatment, rehabilitation, and lost productivity, diabetes costs the American health care system an estimated $100 billion annually. Once a disease associated with middle age (that’s why you’ll sometimes still hear it referred to as “maturity-onset diabetes”), children—some as young as 4—now account for an increasing proportion of the nearly 1 million new cases diagnosed each year. Worse, the prevalence of the disease is increasing at an alarming rate both here and abroad; worldwide, the number of cases of type 2 diabetes is expected to double over next 25 years.

When communication between the mechanisms responsible for

cell proliferation and the mechanisms promoting apoptosis fails, the result is cancer, a population crisis. When insulin signaling fails, the result is a metabolic crisis. Once under exquisite control, blood glucose levels spiral higher and higher, with devastating consequences for the health and well-being of the body.

INSIDE THE BLACK BOX

Herophilus of Chalcedon might have made it into the history books even if he hadn’t discovered the pancreas. Records suggest that this Greek surgeon and anatomist, the beneficiary of a new mind-set free of proscriptions against tampering with the dead, performed the first public dissection of the human body in the fourth century BC. Did those spectators see it, the warty finger of tissue behind the liver, pointing toward the body wall? If so, their testimony has not survived. But we do know that during one of his dissections, Herophilus took note of the structure now known as the pancreas.

Physicians of his time would have been more familiar with the symptoms of diabetes—profound thirst, frequent urination (the name is Greek for “siphon”), rapid weight loss, coma, inevitable death—for descriptions of the disorder date back to 1500 BC. But it would be nearly 2,000 years before anyone connected the pancreas to the condition or before medicine could offer patients more than palliative treatment to ease their suffering. Pancreas means “all flesh” in Greek, and for centuries the name was appropriate. Most considered it little more than a lump of flesh; even the famed Roman physician Galen maintained that it was no more than a cushion supporting the abdominal organs and the large blood vessels coursing through the trunk. Then, in 1642, German physiologist Johann Georg Wirsüng discovered the duct connecting the pancreas and the duodenum, the initial segment of the small intestine. Professor Wirsüng was murdered by an irate student before he could learn more, but investigators who followed up on his observation demon-

strated that the duct was a conduit for digestive secretions. The pancreas was an exocrine gland.

And it was also an endocrine gland. In 1869 a student at the Berlin Institute of Pathology named Paul Langerhans took a second look at the pancreas under the microscope. In addition to the large flat cells surrounding the pancreatic ductwork, Langerhans found islands of small round cells that had never been described by earlier investigators. Apposed to the capillaries rather than the ducts, these cells in the “islets of Langerhans,” as they came to be called, delivered their secretion to the bloodstream instead of the gut. Like adrenaline, this substance was a hormone; practitioners of the new twentieth-century specialty of endocrinology christened it “insulin” (from the Latin “insula,” meaning island).

Remove the adrenal glands and the consequence was Addison’s disease. Remove the pancreas of a dog, Oskar Minkowski and Joseph von Mering of the University of Strasburg reported in 1888, and the unfortunate animal developed diabetes. Conversely, patients with diabetes exhibited degeneration of the islet cells, reported Eugene Opie of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Diabetes, researchers concluded, was an endocrine deficiency disorder; if so, it ought to be possible to treat the condition by replacing the lost hormone, much as hypothyroidism could be treated with extracts of the thyroid gland. In 1921, Frederick Banting and his student assistant Charles Best did, in fact, reverse the symptoms of diabetes in a dog after surgical removal of the pancreas with injections of a crude insulin preparation—proof in principle that the deficiency theory was correct. Within a year the two had successfully treated their first human patient. Insulin quickly became the standard treatment for diabetes.

For many diabetics, insulin was the difference between life and certain death. But as early as the 1930s, endocrinologists discovered that some patients did not respond to insulin. Indeed, when a test was finally developed to measure blood insulin levels in 1960, these

patients were found to have insulin levels that were actually abnormally high, rather than alarmingly low. Insulin-deficient patients were usually young, lost weight, and deteriorated rapidly without insulin treatment. Insulin-resistant diabetics were older, had milder symptoms, and were more likely to be overweight than underweight. Their condition often improved if they lost weight and followed a strict diet, even without insulin.

Diabetes, it seemed, was really two diseases, with similar symptoms and similar sky-high levels of blood glucose but different causes. In the classic, or type 1, form of the disorder, the pancreas falls silent. Patients stop producing insulin because the immune system mistakes pancreatic islet cells for dangerous invaders and destroys them. Insulin-resistant, or type 2 diabetes, on the other hand, is an attention disorder, not a deficiency disorder. The pancreas speaks, but body tissues no longer listen. At first, insulin resistance is silent, because the pancreas does such a great cover-up job. In an attempt to restore balance, it secretes more and more insulin—in effect, trying to get the receptor’s attention by shouting. Instead, glucose levels keep rising, glucose homeostasis deteriorates, and clinical symptoms of diabetes emerge.

Not surprisingly, the identification of insulin receptors with radioligand studies triggered speculation that type 2 diabetes might be the result of a defect in insulin receptors, which compromised cells’ ability to hear and respond to the hormone. However, a closer look at the relationship between insulin binding and insulin activity quickly undermined this notion, says cell biologist Alan Saltiel. Insulin responsive cells, he explains, can lose nearly all of their insulin receptors without affecting their response to insulin. “Cells have far more insulin receptors than they need. You can get full activation by occupying only 10 percent of the receptors on the cell surface. So if you had, say, a 50 percent reduction in the number of receptors, you might expect to see a shift in sensitivity but not in receptor activation. That started a strong emphasis on signal transduction.” The

problem was that before 1981 scientists knew almost nothing about what happened after insulin bound to its receptor.

In the late 1970s, insulin researcher Pierre de Meyts created a cartoon for the journal Trends in Biochemical Sciences to accompany a review article written by Ronald Kahn, who now directs the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston. “It was a picture of a guy pointing to a blackboard with this picture of a theoretical cell,” Kahn recalls. “It showed the insulin receptor and then inside the cell was this black shading and it said ‘and then something happens.’ At the bottom of the diagram it said ‘glucose goes down.’ And the guy pointing to the board is saying, ‘We’ve come a long way since our black box concept.’”

Kahn pioneered the effort to pry open insulin’s black box. “Up until about 1981, we knew that the receptor was a binding molecule, but we really had no idea about its signaling,” he recalls. “Then in 1982 we published a paper that defined the insulin receptor as a receptor tyrosine kinase. And with that we created a mechanism to get the signal inside the cell.”

Like other receptor tyrosine kinases, the insulin receptor has a split personality. In fact, it’s actually two proteins in one, a pair of α subunits that constitute the binding site, and a pair of β subunits that constitute the kinase. When insulin isn’t around to intervene, the α subunits keep their β partners in a headlock, choking off enzyme activity. Insulin binding frees the active site, allowing the β subunits to phosphorylate each other. Active and attractive, the phosphate-decorated receptor has no trouble drawing other binding partners or convincing them they’d look better with a phosphate or two themselves.

Joslin researchers, including Kahn and Morris White, identified the first intracellular substrate of the insulin receptor in 1985, a protein they called simply “IRS (for insulin receptor substrate)-1,” and then a second, IRS-2. A year later they discovered that IRS proteins

bound through their phosphotyrosines to SH2-containing molecules—the next components in the signaling relay. “And that, I think, really set the paradigm,” Kahn concludes.

The number of insulin substrates, however, kept growing. Then again, Kahn notes, insulin does a lot more than micromanage blood glucose levels. It also regulates the storage, synthesis, and release of fatty acids, supervises the construction of proteins, stimulates cell growth and proliferation, offers hints during development, and extends cellular life span. To carry out all of these jobs, insulin activates multiple signaling pathways, shifting from one to the other by selecting different options from its vocabulary of substrates.

“Now we know that something like 10 proteins are substrates for the insulin receptor,” says Kahn. “Almost all of them have multiple phosphotyrosines, which bind many SH2—and some non-SH2—containing molecules. We know that the PI3 kinase pathway is responsible for most of the metabolic actions of insulin and that the PI3 kinase is itself an enzyme composed of a regulatory subunit, which comes in eight forms, and a catalytic subunit, which comes in two. And we know that it [the kinase] activates Akt [another signaling protein] downstream. So if you just look at the metabolic pathways and you consider the receptor, the various receptor substrates, the various isoforms of PI3 kinase, and the molecule Akt, there are literally over a thousand potential combinations of signaling molecules.”

The challenge, he continues, is to select the right combination for each task. Just as stem cells must have a key to liberate cell division from apoptosis, cells responding to insulin must unlock a signaling pathway before they can use it. “We used to talk about insulin and its receptor as being like a lock and key. Now I like to use the analogy of a combination lock,” Kahn explains. “You literally have to dial 25 to the right, 14 to the left, and 16 to the right. If you dial 35 to the right and 12 to the left, you’re doing a lot of the same things, but sometimes that lock just won’t open. The whole thing is

a much more delicate balance of signaling operations than we would have guessed. That’s what gives a hormone like insulin its subtlety.”

In the case of glucose homeostasis, the critical combination is the one that relocates glucose from the outside of cells to the inside. “The transport of glucose is the rate-limiting step in glucose disposal, especially in muscle and fat,” says Alan Saltiel. “In type 2 diabetes, glucose transport is defective. There’s a bottleneck at this step.” Insulin still binds and the receptor still adorns itself with phosphate, but the lock has been broken, the key lost, the combination forgotten. The door to glucose transport is closed, and nothing hormone or receptor can say will open it.

If a molecule of glucose was as small and sleek as a molecule of water, glucose could seep into cells. Instead, it has to be carried in on the back of a dedicated transport protein, GLUT4, shuttled in and out of the plasma membrane by its own fleet of membrane-bound vesicles. Until insulin calls, these transporters are stored, in their vesicles, deep inside the cell, tied to a hitching post researchers believe may be the actin fibers of the cytoskeleton.

The sequestration, liberation, and translocation of GLUT4-containing vesicles is a complicated process, according to Saltiel. “The vesicles have to form. Then they’re sorted into compartments. They’re tethered to a specific location. Eventually they’re released, although only some can actually move. These are tracked, probably by the cytoskeleton. They have to cross a barrier of actin at the membrane, find a place to dock, and finally fuse. All the steps have to work together to control the process.”

Just freeing the transporter-laden vesicles from their tethers—the step regulated by insulin—is complicated. In contrast to the average signaling assignment, this job requires two combinations, each opening a distinct insulin-signaling pathway. “Both pathways are necessary, neither is sufficient. They are independent but coordinated,” Saltiel says. The first pathway follows the sequence outlined

by Ron Kahn: IRS protein—PI3 kinase—PIP3—Akt. The second utilizes a different pool of receptors and a different signaling relay and operates out of a unique location: pockets of plasma membrane known as caveolae, a subtype of the membrane lipid aggregates that cell biologists call “lipid rafts.” The combination that unlocks this pathway begins with an insulin receptor and the substrate Cbl, trucked in to take advantage of the available phosphotyrosine by a protein called CAP. Once activated, Cbl and CAP hitch a ride on the raft, binding to the lipid-loving protein flotillin. Here, they fiddle with a series of adaptors that flip the last pin in the lock, releasing a go-between that communicates with the GLUT4 vesicles.

Convoy! The garage opens, and a steady flow of GLUT4 vesicles heads to the surface of the cell, picks up a load of glucose, and trucks it off to be stored as glycogen or made into lipid.

Researchers now believe that the attention deficit at the heart of type 2 diabetes is almost certainly the result of a subtle defect downstream of the insulin receptor, a disaffected adaptor or inept kinase that alters the meaning of the sentence just enough to render it unintelligible to the GLUT4 and its vesicles. However, cautions Kahn, it doesn’t have to be the same defect in every patient. “What exactly do we mean by the term ‘insulin resistance’?” he asks. “Are all the steps resistant? Only some of the steps? Are some steps more resistant than others? Are they more resistant in some tissues? Individuals probably differ. For researchers that creates a problem finding genes. For clinicians it creates challenges for finding a ‘universal treatment,’ because each patient is different.”

WEIGHT WATCHING: AN EXERCISE IN FUTILITY

“You can talk to each other. That’s allowed,” says Barbara Reynolds. It’s the first night of her seminar “Diabetes and You,” and Reynolds, a nurse-educator at St. Mary’s Hospital in Middletown, Pennsylvania, is trying to help a dozen anxious people recently diagnosed with type 2 diabetes relax. Over the course of the next month, she assures

them, she’ll be able to teach them to understand and cope with their illness instead of fearing it. “I ended up specializing in teaching about diabetes because of my mother,” she tells the group. “She flunked two courses like this—one of them was mine. That was my motive for thinking it was possible to do this better.”

Tonight’s session will focus largely on background information: what diabetes is, how it’s treated, how and when patients should check their blood sugar, when to call the doctor. One week will focus on medication. But most of the time will be devoted to the one issue that vexes people with type 2 diabetes more than any other: food. Most of the people in this room are overweight, and that weight is almost certainly what upset their insulin signaling mechanisms in the first place.

Obesity and type 2 diabetes are best friends. More than 80 percent of people with type 2 diabetes are obese, and many experts argue that the increasing incidence of diabetes can be explained in part by the increase in the American waistline. About 60 percent of the adult population—and 15 percent of children—are currently thought to be overweight. From the standpoint of glucose homeostasis, even a few extra pounds can be detrimental, if they’re in the wrong place. Abdominal obesity—the familiar “pot belly”—is especially likely to lead to insulin resistance and eventually diabetes.

For those who already have type 2 diabetes, losing weight is like getting a hearing aid. When patients shed pounds, their response to insulin improves. As a consequence, their plasma glucose levels stabilize, and their chances of developing serious complications like blindness and kidney failure decrease. That’s why doctors emphasize the importance of weight loss and exercise, and educators like Barbara Reynolds spend so much time teaching about portion sizes and “carb choices.”

Reynolds doesn’t like the word “diet.” “It makes me think of deprivation,” she says. She prefers to call it “meal planning,” stressing how thinking of food this way “puts the choice back in your

hands. You say what you’re going to eat.” But no matter what they call their calorie counting and apples-for-cookies trade-offs, patients are likely to find shedding excess pounds an uphill battle—and they’re not alone. Despite an estimated $30 billion to $50 billion spent each year on diets, drugs, and exercise programs in this country, most overweight individuals trying to lose weight fail; of those who do succeed, about 90 percent will eventually gain it all back.

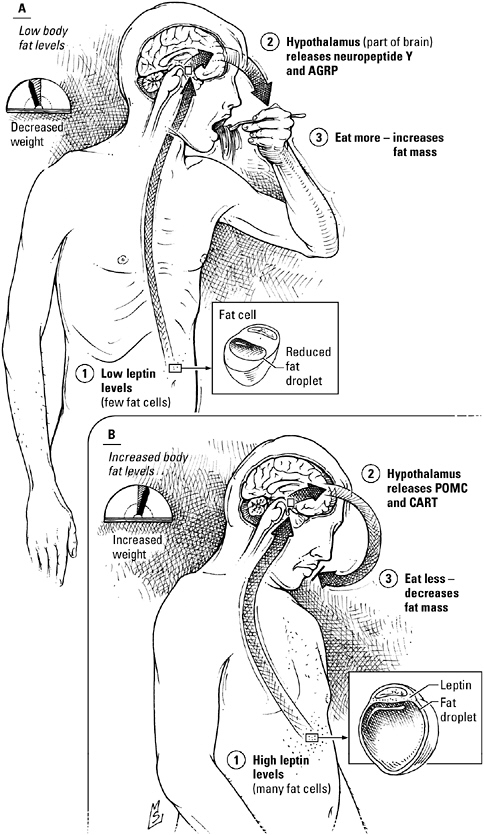

Dieting is so often an exercise in futility because body weight, like glucose levels, is controlled by homeostatic mechanisms. “Biological factors determine body mass, which is then defended,” says Jeffrey Friedman, an obesity researcher at Rockefeller University. “Deviations in weight in either direction elicit a potent counterresponse to resist change.”

The defense of body weight and the troubled relationship between weight and insulin action both feature strong opinions from the most unlikely of orators: the fat cell. Long considered no more animated than a bottle of cooking oil, fat cells, scientists have learned, are every bit as talkative as the pancreas or the adrenal glands. Fat cells, you see, are part of the endocrine system, too.

Jeff Friedman started working on appetite because he didn’t get his fellowship applications in on time. With a year to kill until he could apply again, the aspiring gastroenterologist took a job with Mary Jane Krieg, a neurobiologist at Rockefeller University who studied the biological basis of drug addiction. Krieg gave Friedman the job of perfecting an assay for an endogenous morphine-like peptide, β-endorphin, and suggested he contact another Rockefeller scientist, Bruce Schneider, an expert on the use of antibodies to track and capture proteins, for some suggestions.

Schneider was interested in the neurobiology of feeding behavior and was using the assays as part of his research on a peptide hormone that was secreted by the gut and acted in the brain. The hormone, called cholecystokinin, seemed to signal when an animal