The Language of Life: How Cells Communicate in Health and Disease (2005)

Chapter: 2 Build It and They Will Talk

2

BUILD IT AND THEY WILL TALK

Take a deep breath. Now thank the former bacteria living in each and every one of your cells that the oxygen you just inhaled sustains you rather than kills you.

The hardy cells that pioneered life were remarkably self-sufficient, capable of building their own walls and membranes, re-creating their own DNA, manufacturing their own proteins. But one necessity—the energy needed to power essential chemical reactions—could not be generated by even the most industrious and had to come from outside sources. Life’s first cells made do with resources they found close at hand, tapping the chemical energy of inorganic compounds such as hydrogen sulfide—effective, but limited. Their progeny, however, discovered an inexhaustible alternative directly overhead: sunlight, earth’s most abundant energy source. Chlorophyll, a green pigment able to convert light energy into chemical energy, allowed these innovators to draw on the sun’s plentiful energy reserves to drive the synthesis of carbohydrates they could burn as fuel.

It was a clever and effective way to make a living, fashioning your own food from sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide. But photo-

synthesis also had a downside. The chain of chemical reactions that culminated in energy-rich sugar and starch also generated a noxious pollutant: oxygen, not only useless but dangerous to organisms that had evolved in its absence, wanton in its disregard for the integrity of biomolecules. Life on earth might have corroded like a rusting nail if not for evolution’s uncanny ability to transform potential calamity into opportunity. A vanguard of enterprising organisms upgraded their metabolism with proteins that could harness the volatility of oxygen to increase the amount of energy extracted from carbohydrates. This invention—biologists call it “respiration”—not only protected vulnerable cellular constituents from oxygen toxicity but also enabled its inventors to realize a significant improvement in energy efficiency.

So some lived on geochemicals, some on sunlight. And others lived off the largess of others, solving their own energy problems by devouring their neighbors. Earth’s first predators, they had no teeth or claws but used their own bodies to capture their prey, embracing, then engulfing and digesting it. A meal of oxygen-loving bacteria had additional benefits for one of these lucky predators, however. Just as “it was the horse’s value as a mount, not as a meal, that quickly came to dominate its relationship with man,” it was the victim’s cache of respiratory enzymes, rather than its nutritive value, that proved more valuable to the predator. Instead of being dismembered and digested, these captives were permitted to survive and reproduce. Generation by generation, their descendants gradually ceded most of their DNA to the predator’s genome; trading their freedom for a free ride, the aerobes became permanent houseguests, the cellular constituents we know today as mitochondria.

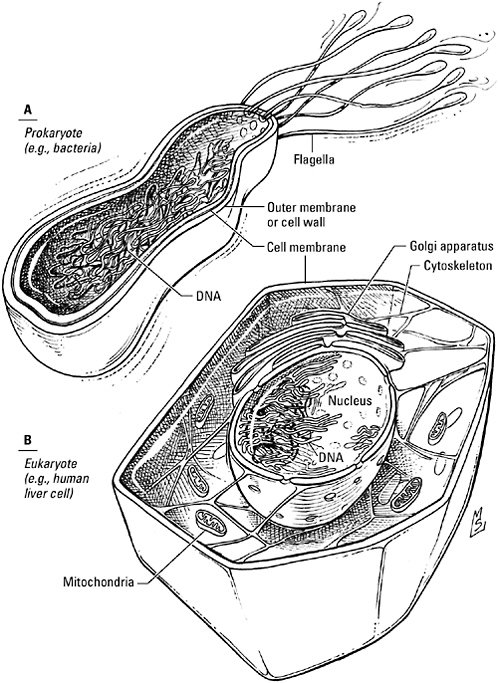

The organism that domesticated a microbe it should have digested was odd in other ways as well. While the sulfur eaters and photosynthesizers preferred an open floor plan and an informal lifestyle—their DNA rolled and stored in a corner, their proteins

unbounded by walls or closets—this creature was a compulsive organizer. Its DNA was enclosed in a membrane-bound bubble, a chance involution of the cell membrane that gave it and its successors their family name: the eukaryotes (from the Greek charyon, meaning nucleus). An advance comparable to the invention of pottery, membranes grew so popular, in fact, that eukaryotes would ultimately appear to have splurged at an evolutionary Tupperware party, stretching, wrapping, and sealing a pliable membrane to form compartments of every shape and size. While they were adding interior walls, they stripped away the stiff outer cell wall favored by prokaryotes. In its place they erected an internal scaffolding of protein rods and filaments, a so-called cytoskeleton, that gave shape to their soft bodies but permitted them to move freely about.

A new social contract arrived along with the new furniture. Bacteria, eager to cohabitate, have never married—even those who settle in cities don’t hesitate to move on if times get tough. But these eukaryotes, just as quick to recognize the many advantages of communal living, lived by the motto “until death do us part.” Their alliances were indissoluble, their commitment to their colleagues, unequivocal. Some—these would become plants—decided good fences make good neighbors after all and surrounded each of their cells with a cocoon of cellulose. Others—the clan that biologists call “metazoans” and we know as animals—forswore rigid walls that prevented real intimacy for good. They dared not only to collaborate with their neighbors but also to touch and even embrace them.

A revamped metabolism, the freedom to bend and move, a lasting marriage, and a physical form that enabled physical contact were more than cosmetic changes—they were adaptations that supported a revolutionary new lifestyle. Yet they also led to formidable new problems in organization and management. For solutions to these problems, eukaryotes turned to a tried-and-true faculty: the gift of speech, embodied in the chemical language of receptors and kinases.

FROM THE GROUND UP

I turn on my cell phone and instead of “Welcome,” the screen announces “Holla!”

Ordered to erase the welcome message “can’t knock the hustle,” my older daughter Jennifer has substituted this. “‘Holla’?” I ask. “Don’t you mean ‘Hello’?”

“No. It’s ‘Holla’.”

“What’s with that?”

“It’s just something we say. Like, if somebody scores at a basketball game, everybody yells ‘Holla!’ Or if I see one of my friends on the stairs, we go ‘Holla!’”

“So if I saw one of my friends in the mall, could I yell ‘Holla, Marie’?”

Jenny rolls her eyes. “Only if you wanted to sound like an idiot.”

“What if I saw you in the mall?”

“Don’t go there.”

“So when do I use it?”

“You don’t. You’re my mother, not my friend.”

As any adolescent can tell you, parting ways with the adults isn’t easy. You can’t live somewhere else, you don’t have a full-time job, and even if you can drive, it’s their car. One way you can put distance between yourself and your parents, however, is to update their language. You can throw away some words, change the meaning of others, and add new ones to put your stamp on every conversation.

Eukaryotes—you could think of them as “Generation E”—had outgrown old-fashioned ideas like oxygen phobia and unprotected chromosomes, but they still had to share living space with bacteria, the older generation. Tinkering with language was one way to distance themselves from their elders, to establish their independence and keep the old folks from learning every detail of their personal lives—information that could be used against them. “As soon as eukaryotes evolved, they had to deal with bacteria,” notes E. Peter

Greenberg, a microbiologist at the University of Iowa College of Medicine. “They needed signals bacteria didn’t recognize, and that’s probably why our signals are different from their signals.”

But an identity crisis was only one of many factors inciting multicellular eukaryotes—particularly metazoans, or animals—to tamper with the language of life. First of all, they were growing faster than my daughters’ wardrobes. In a world still dominated by single-celled organisms (both eukaryotic and prokaryotic), bigger was better; as biologist John Tyler Bonner writes, “There is always an open niche at the top of the size spectrum; it is the one realm that is ever available to escape competition.” Selection for size, Bonner continues, goes hand in hand with “a selection for a better integration, a better coordination of the adhering cells.” The small, limited to brief exchanges with their immediate neighbors, didn’t need an expansive vocabulary or long-distance phone service. The cells constituting larger organisms, however, had to keep in touch with distant relations as well as those next door. Existing options just wouldn’t do; they needed new kinds of signaling molecules, sturdy enough to survive a trip from one part of the body to the other.

For animal cells the freedom to embrace also established a new forum for discussion. Adrift in the primal ocean, they resisted dispersal by clinging tenaciously to each other in a continuous layer known as an epithelial sheet—life’s first true tissue. In contrast to a biofilm, which conforms to the curvature of a rock, the edge of a tooth, or the surface of a pipe, an epithelial sheet could adopt any shape it chose, even curl up and anneal edge to edge to form a tube or sphere. Within such a hermetically sealed compartment, conditions could be specified by the organism, not left to the whims of a capricious environment, and cells could speak without their words being diluted and dissipated by every passing wave. Cellular behavior could be micromanaged by editing the content of this internal milieu—providing, of course, the organism had the words to spell out exactly what cells should do and when.

As if a population explosion and an inner life weren’t enough to manage, there was the building program. Sheets could be fashioned into shapes, populations arranged to form patterns, and tissues assigned specialized tasks, but external features and internal organs did not form spontaneously. They had to be built from scratch, starting with a single fertilized egg—a feat that would have been impossible without contractors and career counselors. To shape head and limbs, gut and heart, brains and bones, multicellular animals needed road maps and directions, words of wisdom to keep embryonic cells on track as they searched for their destiny.

With their lockboxes for chromosomes, their bold exploitation of oxygen, their compulsive use of membranes, their internal skeletons, and their odd ideas about commitment and intimacy, animal cells were as different from their elders as low-rise-jeans-wearing, multiply pierced, skateboard-toting, electronically enhanced modern adolescents are from theirs. Yet the more things changed, the more they stayed the same. Cells, whether prokaryote or eukaryote, had to navigate the same capricious environment, face the same challenges collecting and disseminating information. The availability of resources and the presence of danger, the quality of life and the actions of neighbors, still had to be encoded in a form understandable to genes and proteins, still had to be transferred across an impermeable plasma membrane, still had to be delivered to targets that organized responses. So it’s not surprising that while the conversations of eukaryotes sparkled with new ideas—solutions to the new problems created by their secession from the prokaryotic lineage, their quest to occupy the “niche at the top of the size spectrum,” and the inherent difficulties associated with constructing and operating a larger, more complex body—much about these exchanges was strangely familiar.

But how could evolving eukaryotes be both traditionalists and trendsetters, as plain spoken as bacteria yet at the same time profoundly more articulate? The answer is simple: they were brilliant architects. Answers to age-old questions could still be found in a

common pattern language, in archetypal patterns based on the architecture of molecules (particularly the ornate topography of proteins), in sentences that followed the same law-abiding internal organization as those of prokaryotes. Working from the ground up, cells extended and updated this library of fundamental design elements to adapt the chemical language of life to meet their growing needs. New signals, new substrates, new patterns, new combinations enhanced language skills, but the real differences between the language spoken by eukaryotic cells and the language of their prokaryotic counterparts lay in the scope not the structure of that language, in the breadth and elegance of the vocabulary, and the intricacy of sentences, rather than in the wholesale redesign of fundamental mechanisms.

Linguists debate the existence of a “universal grammar,” an internal structure common to all languages, genetically programmed into the human brain. For cell biologists there is no debate. The language they study, the pattern language of cells, undeniably possesses a common internal structure. Elemental patterns and established rules of syntax, as familiar to E. coli as they are to human beings, constitute the universal grammar, part of the legacy of every cell.

A SURFEIT OF SIGNALS

Feeling under the weather? Tired, feverish, congested? Today, a doctor would probably attribute your symptoms to this season’s flu virus. If you were a patient in ancient Greece, however, your physician would have known nothing of viruses and infections. He would have blamed the problem on an imbalance in bodily secretions called humors, each representing one of the four elements thought to compose all matter: yellow bile, associated with fire; phlegm, cold and wet like water; blood, corresponding to air; and black bile, dark and inert as earth.

The Age of Mythology gave way to the Age of Reason, and the

humors of the Greeks were relegated to museums along with the statuary and temple artifacts. But secretions responsible for health and well-being are still very much with us; today, we know them as “hormones,” from the Greek hormao, meaning “I excite.” Carried from speaker to target by the blood, these sturdy chemical messengers were the perfect solution to one of the quintessential problems facing multicellular eukaryotic organisms—coordinating the behavior of cells separated by long distances.

Bacteria may have been the first to use chemical signals, but the first chemical signals discovered by scientists were hormones, in particular the secretions of the so-called endocrine, or ductless, glands: the thyroid and the adrenals, the pancreas, the testes, and the ovaries. The knowledge that these glands had far-reaching effects on body functions predates even the Greeks, for farmers and herders have been familiar with the profound changes in appearance and behavior that accompany castration, the surgical removal of an endocrine gland, for millennia. And the idea that these effects were mediated by glandular secretions took shape more than 200 years ago, when Theophile de Bordeau, court physician to Louis XV, speculated that “each gland … is the workshop of a specific substance that passes into the blood, and upon whose secretions the physiological integration of the body as a whole depends.” By the middle of the nineteenth century, scientists could cite clinical observations that supported Bordeau’s hypothesis. “A diseased condition” of the adrenal glands, for example—now known as Addison’s disease, after the English physician Thomas Addison, who published the first description of the condition in 1855—disrupted cardiovascular function, digestion, and appearance: “The leading and characteristic features of the morbid states to which I would direct attention are anaemia, general languor and debility, remarkable feebleness of the heart’s action, irritability of the stomach, and a peculiar change of color of the skin … with the advance of the disease … the pulse becomes weaker and weaker, and without any special complaint of

pain or uneasiness the patient at length gradually sinks and dies,” while damage to the thyroid gland was toxic to the mind as well as the body—“cretinism” they called the result.

Cries of help from tissues deprived of some vital elixir only the adrenal gland or the thyroid gland could supply, some argued. But until someone actually isolated such a substance, any conversations initiated by the endocrine glands would remain confidential, and the simplest farmer would know as much about cellular communication as the most learned academic.

On an otherwise ordinary day in 1894, Edward Albert Schäfer, professor of physiology at University College London, was recording the blood pressure of a dog as part of a routine experiment when he was interrupted by a stranger with a vial of a mysterious substance and an urgent request. Dr. George Oliver introduced himself—taking care to note that he too was a former student of Schäfer’s revered mentor, William Sharpey—and explained that when he was not treating patients he spent much of his time in a modest laboratory he’d set up in a back room of his home, designing medical instruments he then tested on family members. His latest invention was an “arteriometer,” designed to measure the diameter of a blood vessel through the overlying skin; to try out this device, he had injected his son with glycerin extracts of various animal glands and recorded changes in the diameter of the boy’s radial artery.

Oliver admitted that most of the extracts had done nothing. But one, prepared from the adrenal glands, had triggered a spectacular constriction of the artery. Didn’t the professor agree that this might mean the extract contained one of the glandular secretions so keenly sought by scientists? Oliver handed the vial to Schäfer and exhorted him to inject some of the liquid it contained into the dog lying on the table. And Schäfer—perhaps merely curious, perhaps a bit intimidated by Oliver’s fervor—agreed:

So, Professor Schäfer makes the injection, expecting a triumphant demonstration of nothings, and finds himself, like some watcher of the skies when a new planet swims into “his ken” watching the mercury rise in the manometer with surprising rapidity and to an astounding height, until he wonders whether the float will be thrust right out of the peripheral limb. So the discovery was made of the extraordinary active principle of the suprarenal gland.

Chemists—John Jacob Abel and Jokichi Takamine—took over next. They plied the crude extract with acids and solvents and ammonia; by the turn of the century, they had succeeded in purifying the “active principle.” Abel called the substance “epinephrine,” and Takamine “adrenaline,” after the gland that secreted it.

Cells could talk—and over what distances!—by exchanging chemical signals, molecules produced and excreted by cells of the endocrine glands and carried to cells in target tissues by the bloodstream. But hormones (following the purification of adrenaline, chemists also isolated cortisol, the missing factor in Addison’s disease, from the adrenal glands, as well as thyroxine from the thyroid gland, estrogen and progesterone and testosterone from the gonads, insulin and secretin from the pancreas) represented only one of the many new types of words that animal cells added to their vocabularies. Conversations with the cells next door did not become obsolete just because they couldn’t be heard on the other side of the body, and so short-range signals, as well as novel ways of deploying them, proliferated as well. Development, for example, relied heavily on signaling molecules that never strayed from the neighborhood where they were made and secreted. Neurons, the cells comprising the nervous system, pioneered a new type of interface for conducting one-on-one conversations, and recruited dozens of new substances—small molecules, peptides, even gases like nitric oxide—to encode their messages. Membrane-bound signals set up lines of communication between the gelatinous matrix surrounding cells and the cytoskel-

eton supporting them. Cells of the immune system improvised signals from the dismembered bodies of pathogens. Even death had its own dialect.

To find these new signals, eukaryotic cells, like bacteria, didn’t have to look any farther than their own backyards. Built from chemicals, operated and maintained by chemicals, and fueled by chemical reactions, they lived in a dictionary. If a stray metabolite, a common nutrient, or a by-product already on hand wasn’t quite right, or if they were still at a loss for words, they could always turn to proteins for ideas. Thanks to a constantly evolving genome, new models were always coming on the market—enzymes born to be wordsmiths or precursors pregnant with prospective signaling peptides. Adrenaline, for example, is just the amino acid tyrosine dressed up in fancy clothes, the neuronal messengers norepinephrine and dopamine, by-products of the same synthetic process. Testosterone, the hormone that creates boys and turns them into men, begins life as cholesterol, as do estrogen, progesterone, and cortisol. Many growth factors are proteins, insulin and secretin are peptides—new signals but manufactured according to time-honored procedures.

Biodiversity—the mosaic of life forms populating an ecosystem—confers the resilience that enables that system to respond to a variety of environmental challenges. A diversity of signaling molecules provided evolving eukaryotic organisms a similar flexibility to meet the challenges posed by new internal contingencies. Whether the situation demanded a subtle phrase appreciated only by intimates, a hearty greeting to faraway relations, words with a lasting impact, or words quickly forgotten, their cells found a way to say it—an innovation essential to the survival of the vulnerable ecosystems contained in their bodies.

COULD YOU REPEAT THAT PLEASE?

Paul Ehrlich’s nineteenth-century professors called him disorganized, incorrigible, unteachable. A modern educator would probably call

him a “visual learner.” While other medical students spent long hours in the library preparing for exams, Ehrlich spent hours in the laboratory coloring tissue sections with dyes created by the burgeoning German chemical industry, far more fascinated by the unique patterns they created—one stained only the cytoplasm of cells, another only nuclei, a third bacteria, the one in the bottle next to it, the cells they attacked—than by the anatomy of the hand or the names of bones. Who would have thought such an indifferent student would ever become a doctor or that the diphtheria and tetanus antitoxins he began investigating in his own laboratory would interact selectively with the noxious secretions of these pathogens alone, a specificity that recalled that of the dyes he’d tinkered with in medical school?

Other professors called John Newport Langley brilliant. A contemporary of Ehrlich, Langley was a respected Cambridge physiologist, the first to describe the so-called autonomic nervous system that relays nerve signals to body organs, as well as a fellow of the Royal Society, president of the Neurological Society of Great Britain, editor of the Journal of Physiology, and the recipient of dozens of honorary awards. Who would have thought such a virtuoso would have anything in common with a man who was the despair of his teachers? Yet Langley was also fascinated by the selectivity of chemicals (drugs in this case), how each seemed to home in on some tissues and ignore others. Both nicotine and the South American arrow poison, curare, for example, were attracted to muscle—yet the first stimulated contractions, while the other blocked them.

Despite their differences, both men also came up with the same explanation for such specificity: physical attraction. A dye stained certain structures and not others, Ehrlich suggested, because it bound to some component found only in those structures. Diphtheria anti-serum neutralized the poisonous secretions of diphtheria bacteria because it recognized a structural feature peculiar to that toxin; in the body, cells fell victim to bacterial assault because they also contained a feature—Ehrlich called it a “side chain”—that matched a

loop or groove in the toxin molecule. Similarly, Langley proposed that drugs formed “compounds” with a “receptive substance” on the surface of the muscle cell and suggested that compounds like nicotine and curare canceled each other’s actions because both vied for this same target.

“Corpora non agunt nisi fixata,” Ehrlich concluded. “Agents cannot act unless they are bound.” Pharmacologists agreed, and endocrinologists reasoned that hormones, too, probably exerted their biological effects by binding to receptors. The idea was so commonsensical, yet for half a century after Ehrlich and Langley first posited the existence of “side chains” and “receptive substances,” receptors themselves remained as elusive as hormones once had. “Receptors had no basis in fact; they were more of a metaphysical entity. No one had any thought of what they might be,” explains Nobel Prize–winning pharmacologist Alfred G. Gilman. Scientists could see their handiwork in muscle contractions or the constriction of an artery, but the tales told by such reactions were only hearsay, events several steps removed from the actual binding site. As a result, says Gilman, “People were spectacularly clueless about how signaling might occur.”

Once again, adrenaline would animate a theory, replace metaphysics with molecules. Matriarch of hormones, it still had stories to tell, this time about the nature and behavior of receptors, beginning with the mysterious mechanism that translated the binding of a hormone at the surface of a cell into a response on the other side of the plasma membrane.

A body pumped up on adrenaline can’t run on thin air. Fighting and fleeing are high-energy activities, fueled by the breakdown of glucose. Running out during an emergency could be catastrophic; fortunately, the liver maintains a reserve supply, harvested from the bloodstream in times of plenty and stored in polymer form as glycogen as well as an enzyme, glycogen phosphorylase, able to

deconstruct the polymer. Congenitally lazy, however, glycogen phosphorylase spends most of its time sleeping, the sweet taste of sugar no more than a dream. Snug under a soundproof quilt of cytoplasm and membrane, the enzyme might never hear the clanging of a catecholamine if not for the efforts of the adrenergic (adrenaline-specific) receptor.

The receptor, Earl Sutherland learned, is a typical manager—it doesn’t rush off and wake up glycogen phosphorylase itself; instead, it delegates the job. An apprentice at the time to biochemists Carl and Gerty Cori, Sutherland, along with fellow future Nobel Prize winners Edmond Fischer and Edwin Krebs, learned in the early 1950s that the adrenergic receptor activates a kinase (now known, aptly enough, as “phosphorylase kinase”) and the kinase is the alarm clock that actually rouses glycogen phosphorylase. But if he wanted to know more about this relay, Sutherland realized, he was going to have to pull back the covers and find out how receptor and kinase interacted on the underside of the plasma membrane, after the interaction of receptor and adrenaline on the outside.

Disrupt the membrane and expect a receptor to behave normally? Biologists agreed one might as well crack open an egg expecting a live chick to hop out. “It was almost the definition of a hormone, that its effects could only be observed in the intact cell—if you broke up the cell, the hormone effect went away,” observes Gilman. Fortunately, he adds, Earl Sutherland was a lucky man. Along with colleague Theodore Rall, Sutherland discovered that liver cells could be ground to a pulp without compromising adrenaline’s ability to activate glycogen phosphorylase. In fact, Sutherland and Rall found that they could spin the slurry in a centrifuge to separate receptor and enzyme entirely (glycogen phosphorylase, a cytoplasmic protein, floated in the fluid portion at the top, while the membrane fragments containing the receptor settled to the bottom), put them back together again in a test tube, and recover a response to adrenaline as robust as that found in a living cell.

If the receptor was a protein—and Sutherland and Rall assumed it was—it ought to fall apart when heated. So as a control they added adrenaline, then boiled the membrane fragments to destroy the receptor before recombining them with the cytoplasmic fraction. But to their surprise the hormone had still managed to activate glycogen phosphorylase. They concluded that the sequence from receptor to enzyme must contain yet another go-between, and it was not a protein. This hardy molecule, Sutherland learned, was a nucleotide—an amalgamation of a sugar, a nitrogen-spiked moiety or “base,”and phosphoric acid—related to the ATP (adenosine triphosphate) cells relied on to power chemical reactions but bent into a ring and decorated with a single phosphate group instead of three, a structure reflected in its chemical name: “cyclic-3′, 5′-adenosine monophosphate,” or “cyclic AMP” for short. He called this adrenaline-by-proxy a “second messenger” because it repeated the command first issued by adrenaline. “It was a biochemical, rather than physiological, demonstration of receptor activity, one of the first times you could think of receptors in real biochemical terms,” concludes Gilman.

Within a few years it would be possible to think of receptors in even more intimate terms. The study of cell signaling was about to enter the Nuclear Age.

Hydrogen: small, light, invisible. Iodine: a reminder that life began in the sea. Carbon: black scaffold of life. Phosphorus: so volatile it ignites spontaneously. Sulfur: the biblical brimstone. Nuclear chemists can induce all of them to form radioactive isotopes, a transformation that changes their destiny—they will now inevitably, inexorably, disintegrate—but not their basic chemical nature. Recruited as substitutes for their naturally occurring, stable counterparts, radioactive atoms readily assume the same roles in chemical reactions. But they are as conspicuous in the finished product as the nonconformist neighbor who lets his lawn “go natural” and paints his shutters pink, meaning that the activities of the molecules har-

boring them can be monitored as readily as the movements of a wild animal fitted with a radio transmitter.

Radioactive tracers took the secrecy out of biomolecular behavior. Nutrients spiked with radioisotopes exposed synthetic pathways to public inspection. Radiolabeled amino acids recounted the life stories of proteins. Woven into DNA and RNA, radioactive nucleotides charted the course of cell division and the transcription of genes into RNA recipes for proteins. And with radiolabeled hormones and drugs acting as reporters, scientists could finally relish eyewitness accounts of the long-clandestine interactions between receptors and signaling molecules.

Cyclic AMP turned out to be a popular word. In the decade following Sutherland’s discovery of the molecule, scientists discovered at least a dozen other hormones and neurotransmitters, in addition to adrenaline, that utilized it as a second messenger. In fact, by 1969 so many scientists had become interested in such receptors that it seemed as if “half the world at the time was studying cyclic AMP,” recalls biochemist Robert Lefkowitz. The investigators supervising Lefkowitz’s postdoctoral research at the time, biochemists Ira Pastan and Robert Roth, were part of the wave. They were especially intrigued by the idea of hunting down cyclic AMP–dependent receptors with the new radioactive tracers, and so “the project they cooked up for me was studying adrenocorticotropic hormone—ACTH—using 125I-ACTH,”* he explains. The assignment led to a paper in the prestigious journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, “the first description of a receptor that acted through cyclase”—and the first entry in a scientific bibliography that now includes more than 500 publications.

But Lefkowitz had no intention of devoting his entire career to

ACTH receptors. His real passion was adrenaline, his goal to use similar “radioligand” binding assays to study its receptors. “On the emotional side,” he notes, “I was a fellow in cardiology at the time and I wanted to do something which would have immediate relevance to clinical medicine.” And on the practical side, peptide hormones “were harder to work with, and there were few compounds that interacted with their receptors. In the case of epinephrine, there were hundreds of compounds.”

That “side chain” idea had filled Paul Ehrlich’s head with dreams of miraculous cures—and the shelves of pharmacies with new medicines. Extrapolating from the specificity of his dyes and antitoxins, Ehrlich argued that it ought to be possible to identify chemical agents with a similar specificity for pathogens, “substances which have an affinity to the cells of the parasites and a power of killing them greater than the damage such substances cause to the organism itself, so that the destruction of the parasites will be possible without seriously hurting the organism.” He called the concept “chemotherapy” and demonstrated its legitimacy with his discovery of the arsenic derivative arsphenamine, or Salvarsan, the first man-made anti-infective agent. Following the same line of reasoning, physiologists-turned-drug-prospectors panned for drugs that would bind to the “side chains” recognized by endogenous signaling molecules, replicating or blocking their action. In the case of adrenaline, the hunt had been especially productive, providing physicians, as Lefkowitz points out, with an entire pharmacopoeia of drugs attracted to adrenergic receptors: drugs to shore up failing hearts, reduce soaring blood pressures, cheer depressed brains, neutralize life-threatening allergic reactions, and dilate airways throttled by asthma.

Lefkowitz selected promising members of this library and tagged them with the radioisotopes 125I or 3H, then offered them to the red blood cells of frogs and turkeys, fat cells and lymphoma cells, membranes from heart and brain. He counted receptors and compared the rate and affinity of binding to the efficacy of the drugs in physi-

ological assays. He set up contests between his radioligands and unlabeled adrenergic drugs, calculated their affinities (the strength of the interaction between drug and receptor), and used these values to construct pharmacological profiles of the receptors in various tissues. His profiles corroborated an odd feature of adrenergic receptors first described by pharmacologist Raymond Ahlquist in the 1940s: they had multiple personalities. Those located on blood vessels, for example, responded vigorously to adrenaline but only tepidly to the adrenaline-like drug isoproterenol (Ahlquist had called these “α [alpha] receptors”), while those in the heart were their mirror image, preferring isoproterenol to either epinephrine or its precursor norepinephrine (these he called “β [beta] receptors”). The binding assays differentiated α and β receptors more emphatically than bioassays; in fact, drug profiling suggested they could be subdivided even further: α receptors into two groups (α1 and α2); β receptors into three (β1, β2, and β3).

Once researchers like Lefkowitz could get close to adrenergic receptors with binding assays, it also became realistic to think about extracting the receptor protein from the membrane and purifying it—using radioligands to track the protein during the rough-and-tumble purification process—dissecting it into its constituent amino acids, even cloning its gene. Not that receptors submitted to captivity meekly. Like other membrane proteins, they were maddeningly agoraphobic, loathe to abandon their familiar lipid-rich environment, quick to unravel and collapse if treated too harshly. Nonetheless, by 1982, Bob Lefkowitz and his co-workers had corralled the β2-adrenergic receptor; by the end of the decade, they had purified β1- and α-adrenergic receptors as well—proof that receptor subtypes were actually distinct proteins, not experimental artifacts.

Once they’d cloned the gene for the β2-receptor and deduced something of its internal structure, it was not difficult to see why the protein had been so recalcitrant either—it was woven into the very fabric of the plasma membrane. Seven hydrophobic segments, each

coiled into a helix, pierced the membrane, connected by loops of hydrophilic residues that protruded into the watery environment on either side. Viewed in cross section, the receptor appeared to have been sewn in place by an amateur who forgot to secure the ends of the thread, a baggy running stitch of a protein with one end draped across the surface of the membrane and one dangling in the cytoplasm.

Earl Sutherland discovered adrenaline’s intracellular surrogate. Bob Lefkowitz put its receptors on display. Martin Rodbell added one receptor and one enzyme and came up with three components.

A COMMUNITY OF EFFORT

The son of a Baltimore grocer, Rodbell might have been a chemist—he did his doctoral research on phospholipids, the most important ingredient in your standard cell membrane. Or he might have been a poet—he’d studied French existential literature in college and liked to embellish scientific presentations with original poems. He might even have become a mathematician or an engineer, given his fascination with the avant-garde field of cybernetics—the term invented by Norbert Wiener to describe mechanisms common to machines and biological organisms—particularly the branch aficionados were calling “information theory.” Instead, he chose endocrinology. He would study the compositions of cells rather than those of poets, by translating the language of life into the language of machines.

Where some saw a liver cell, Rodbell saw a tiny computer. “The living cell,” he would later write, “is in essence a communication device, built primarily of organic matter rather than the silicon of today’s computers.” Drawing an analogy to the circuitry common to modern electronic devices, Rodbell proposed that “signal transduction”—the transfer of information from the external environment to the inside of the cell—required a sensor component, or “discriminator,” to detect chemical signals, the data in this system; an output

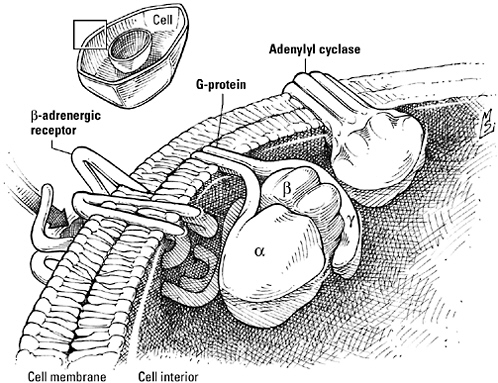

component, or “amplifier”; and, in addition, a third component, a “transducer,” that did the actual work of converting the signal detected by the discriminator into a form that could be understood and converted into a response by the amplifier. In the adrenaline-adrenergic receptor-cyclic AMP system, for example, the receptor played the role of discriminator, and the enzyme that generated cyclic AMP, which had been christened “adenylyl cyclase,” was the amplifier. What Rodbell’s transducer might be—if it even existed in living cells—was anyone’s guess.

The search for the transducer began with the receptor. Using the peptide hormone glucagon to stimulate adenylyl cyclase in liver cells, Rodbell decided to warm up with a few standard-issue experiments—radioligand binding studies with radioactive glucagon, assays to measure the output of cyclic AMP at different hormone concentrations—that should have been a mere formality. They weren’t. Radiolabeled glucagon behaved strangely in the test tube, and the results of the binding studies did not mesh with the results of the cyclic AMP assays, even though both were carried out under the same conditions.

For Martin Rodbell, this apparent setback was a breakthrough. As he looked back over the experimental protocols, he noted that both assays contained ATP—the starting material for cyclic AMP and also the source of many a headache for biochemists. “Realizing from painful experience as a graduate student that commercial preparations of ATP contain a variety of contaminating nucleotides,” he wrote afterward, “I tested many [other] types of … nucleotides.” As he suspected, the “ATP” he’d bought from a scientific supply company was, in fact, contaminated with significant quantities of “another type of nucleotide,” called guanosine triphosphate, or GTP. GTP would have been insulted by the suggestion it was a mere impurity, however. Adenylyl cyclase, it turned out, liked having its ATP spiked with GTP; offered the real thing, it quit making cyclic AMP.

Rodbell proposed that GTP was needed to jump-start the cyclase because this nucleotide manipulated the transducer to promote

the orderly transfer of information from receptor to enzyme. What’s more, using a radiolabeled analog of GTP, he identified a guanine nucleotide binding site in liver cells distinct from the binding site for glucagon. Subsequent studies showed that the transducer/binding site not only attached itself to GTP but devoured it as well, using a molecule of water like a crowbar to pry off a phosphate group and turn GTP into guanosine diphosphate, GDP. In other words, this component—Rodbell called it an “N protein”; his successors preferred the term “G (for guanine nucleotide) protein”—like protein kinases, was a phosphate-driven switch. The receptor was the finger that toggled the switch, adenylyl cyclase, the object of its machinations. In the absence of hormone, GDP was snuggled in the binding site, and the G protein was switched off. When the receptor got fired up by the binding of hormone, it drove the GDP out, allowing a molecule of GTP to take its place. Now the switch was on. The activated G protein stimulated adenylyl cyclase, then snapped a phosphate from GTP to regenerate GDP and reset the switch.

Even bacteria value such “GTPases”—who wouldn’t find such a simple switch useful around the house? But only eukaryotes had the genius to incorporate them into signaling pathways. The transducer Rodbell discovered interceding for glucagon, subsequently christened “Gs” because it stimulates adenylyl cyclase, was, in fact, only the first of what has proven to be an extended family of such G proteins. Another, Gi, inhibits the production of cyclic AMP. A third, Gq, activates the enzyme phospholipase C, prompting the synthesis of another second messenger. The one known as Gt serves rhodopsin, the “light receptor” of the visual system, while others work hand in hand with receptors for hundreds of odors.

Rodbell referred to the transducer as a protein, but it was not at all clear that this element was, in fact, a separate molecular entity. “There was no compelling reason to believe that the guanine nucleotide binding site was on a separate protein; it could have been intrinsic to the receptor or the effector protein [adenylyl cyclase],” Alfred Gilman explains.

Gilman took up where Rodbell left off, recognizing that the only way to determine if the G protein was part of the receptor, part of the enzyme, or a third protein was to try to isolate it. “Al Gilman and I were on a parallel course for nearly a decade,” says Robert Lefkowitz. “What I was trying to do with β receptors, he was trying to do with G proteins.”

You could say Alfred Goodman Gilman was born to be a pharmacologist. His father, Alfred Gilman, was not only a respected professor of pharmacology—the first chair, in fact, of the pharmacology department at Albert Einstein College of Medicine—but also (along with Louis S. Goodman) co-editor-in-chief of one of medicine’s best-known and most-respected texts, The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, now in its 10th edition. “As my friend Michael Brown once said, I am probably the only person who was ever named after a textbook,” Gilman the Younger notes.

As a child, Gilman, inspired by trips to the Hayden Planetarium, wanted to be an astronomer, but fate seemed to have hitched his star to adenylyl cyclase. Earl Sutherland (of cyclic AMP fame) was a family friend. He persuaded Gilman to accept a place in a new M.D.-Ph.D. training program at Western (now Case Western) Reserve University; there, Theodore Rall, Sutherland’s former collaborator, became Gilman’s graduate advisor. After receiving his degree, Gilman tried to switch to brain research, signing on as a postdoctoral fellow with neurobiologist Marshall Nirenberg at the National Institutes of Health. Instead, his new mentor put him to work designing a better assay for cyclic AMP. Gilman finally capitulated. He gave up on the brain and took on the task of purifying Gs instead.

Where Lefkowitz used radiolabeled drugs, Gilman used lymphoma cells with a curious genetic defect. The parent strain, a common laboratory cell line known as S49, suffered from what toxicologists would call an “idiosyncratic drug reaction”—exposed to the rush of cyclic AMP generated by adrenergic drugs like isoproterenol, they died in their dishes. The mutant variety of S49 cell survived. Their resistance to the lethal effects of cyclic AMP, Gilman

and others learned, wasn’t the result of a defect in adenylyl cyclase—the enzyme was fine. And the mutants had plenty of fully functional adrenergic receptors. The problem was at the level of the G protein; as a consequence, Gilman and colleague Elliot Ross reasoned, they should be able to determine if a protein isolated from normal cell membranes was, in fact, the sought-after G protein by introducing it into mutant S49 cells, treating the cultures with isoproterenol to increase cyclic AMP, and seeing if the cells lived or died. “What was needed was to rejoin the missing link,” he explains.

By 1980, Gilman and his colleagues had succeeded in purifying a protein that met the criteria for a bona fide G protein—actually a protein alliance, for Gilman discovered that a G protein is really a confederacy of three polypeptides. Gα, the largest, is also the busiest: the subunit that initiates the collaboration with receptors, it also binds guanine nucleotides, strips GTP of its phosphate, and activates adenylyl cyclase (and other effectors). Gβ and Gγ are Siamese twins. In a dormant G protein the three subunits cling to each other, forming a single complex. When Gα ejects GDP, however, Gβ and Gγ get booted out as well. After Gα has gotten enzyme prodding and nucleotide trading out of its system, the others return to the fold, regenerating the original tripartite protein.

Once thought to be superfluous or at best, supportive, today the Gβγ duo is recognized to be an important intermediary in its own right, linking G protein–coupled receptors to other signaling relays, in addition to the one headed by adenylyl cyclase. “It’s now appreciated that the separation of Gα and Gβγ represents a real branch point in signaling,” Gilman explains. “βγ complexes regulate downstream effectors as much as Gα does.” When the G protein is inactive and all three subunits are bound together, he continues, “the interaction between α and βγ mutually occludes the surfaces that each uses for downstream interactions. Subunit dissociation liberates sites of interaction on both Gα and Gβγ.”

In addition to the G protein amino acid sequence, Gilman and

others now have pictures of one of these proteins, the inhibitory G protein Gi. Because Gi is among the rare proteins willing to strike a pose for crystallographers (most balk at the thought of sitting still in crystal formation), they have been able to reconstruct its three-dimensional structure from X-ray diffraction patterns and magnetic resonance spectra. They can show you Gα hanging from the plasma membrane by its fingernails and trawling for hormone-activated receptors. Look at Gβ and its unshakeable sidekick, Gγ, straddling Gα’s switch region; no wonder they’re popped off when that switch snaps shut. Fortunately, as you can see, Gβ, shaped like a seven-bladed propeller, looks as if it’s ready to travel. And Gγ is a born passenger. Slung across its partner’s shoulder, it just holds on and takes in the scenery, one end trailing like a ribbon in the breeze.

“Put it down in my mind to great insight and intuition that a third piece had to be there,” says Gilman, who shared the 1994 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Martin Rodbell for their work on G proteins. Rodbell himself credited teamwork, comparing his discussions with co-workers to the conversations between cells. “Biological communication,” he said in his acceptance speech, “consists of a complex meshwork of structures in which G proteins, surface receptors, the extracellular matrix, and the vast cytoskeletal network within cells are joined in a community of effort, for which my life and those of my colleagues is a metaphor.”

GPCR. No, it’s not the name of a new alternative rock band. It’s an abbreviation for “G protein–coupled receptor,” one of the names researchers have given the β-adrenergic receptor, the glucagon receptor, the ACTH receptor, and all the others that communicate through a G protein transducer. You could also call them “7TMRs,” for “seven transmembrane receptors”; if you don’t like abbreviations, call them “heptahelical receptors,” or “serpentine receptors,” for the way they flow sinuously across the plasma membrane. You’ll never be wrong, for all 800-odd proteins that belong to the G protein–

The β-adrenergic receptor, a G protein-coupled receptor. Like other members of this expansive receptor family, the β-adrenergic receptor is actually the first element of a three-protein phrase that also includes a G protein (in this case, Gs), a GTP-driven switch, and an effector, here the cyclic-AMP-generating enzyme adenylyl cyclase. The binding of signal to the receptor triggers the release of GDP from the Gα subunit of Gs, subsequently replaced by GTP, and the dissociation of Gα from the Gβ and Gγ subunits. GTP-activated Gα then stimulates adenylyl cyclase, increasing the generation of cyclic AMP, while the Gβγ duo goes its own way and speaks to other signaling relays.

coupled receptor family have the same seven-helix, membrane-spanning structure. “We were shocked,” insists Bob Lefkowitz, who discovered the pattern when he found that his newly sequenced β2-adrenergic receptor and the G-protein-coupled light receptor, rhodopsin, were look-alikes. “It came as a complete surprise. But the importance was recognized immediately.”

Animal cells haven’t discarded sensor kinases or receptors that double as transcription factors. Nor did their innovations in the re-

ceptor department begin and end with G protein-coupled receptors; all told, scientists have described at least 16 different varieties of receptor listening for signals in these cells. But multicellular animals begin more sentences with a receptor-G protein pair than with any other introductory word or phrase. A new take on an old idea—the transmembrane receptor—GPCRs illustrate how multicellular eukaryotes used simple design elements as the basis for larger patterns that expanded their language skills. Versatile and productive, these receptor phrases can be found controlling every type of physiological function in metazoan organisms, from simple housekeeping chores like the disposition of glucose to the intricate machinations of the brain.

SNAP TO IT

If cells were editors, they’d point out that the complete sentence, as spoken by the adrenal gland to the liver cell, goes like this: “adrenaline—β-adrenergic receptor—Gs—adenylyl cyclase—cAMP—cyclic AMP protein kinase (or “PKA”; heading the relay between receptor and target, it’s the first protein to heed cyclic AMP’s call)—phosphorylase kinase (Sutherland’s kinase, it’s phosphorylated and activated by PKA)—glycogen phosphorylase—THEN—Gβγ—G protein-coupled receptor kinase (“GRK,” for short)—β-adrenergic receptor (phosphorylated by GRK)—β-arrestin—OR—PKA—β-adrenergic receptor (phosphorylated by PKA)—Gi—AND THEN”—well, more about that in a moment.

It’s a mouthful, compared to the terse commands issued by prokaryotes. Yet despite the extra words, the speech still observes the same conventions as V. fischeri’s demand for light or the spore-making commands of B. subtilis. Hormones, G proteins, second messengers—these are new and creative, but beginning a sentence with the binding of a signal to a receptor is a tradition observed anytime, anywhere, that cells gather together. Kinases remain the backbone of the workforce; they have simply chosen new substrates; specifically,

serine, threonine, and tyrosine. Messages are still handed from protein to protein, only the number of steps from receptor to target has increased.

Admittedly, creativity and eloquence posed challenges. Composed haphazardly, with proteins out of sequence, longer sentences could easily degenerate into nonsense. The mail could languish undelivered if the elements of a relay were scattered to the four corners of the cell or if an essential kinase was trapped in the crosstown traffic of a busy cell. And signaling proteins used once and then discarded were a senseless luxury; cells would have needed even more proteins—and more genes—every time they had something new to say.

Coherence, order, and efficiency demanded a way to connect and share signaling proteins. The answer? Conjunctions. Taking advantage once again of the unique structural features of proteins, eukaryotic cells came up with a design element that was the molecular equivalent of “and” or “or.” A pattern without precedent, this new kind of signaling protein neither manipulated phosphates nor activated enzymes but evolved specifically to forge connections. Variously called linker, adaptor, or scaffolding proteins, the new connectors were mortar and magnet to eukaryotic cells, bridging the gaps between signaling elements, preventing errors that could lead to catastrophic misunderstandings, and conserving genetic resources by increasing the versatility of the proteins they connected.

Imagine you’ve just finished painting the living room, and now it’s time to fold up the drop cloth you put down to protect the carpet. You could wrestle with the damn thing yourself. But wouldn’t the job be easier if you had a helper, folding from one end while you folded from the other?

If proteins were painters, they’d have that floor clear in no time—for them, folding is always a group effort. That’s because the amino acids that make up a protein are organized into blocks called do-

mains. Each domain, a segment of 40 to 350 amino acids, assumes responsibility for folding that part of the protein, then works with the others to complete the job.

Domains, biologists believe, may have started off as proteins themselves. Over time the genes encoding them were inadvertently duplicated or fused with other genes to form a composite gene that encoded a new, larger protein. Although they had lost their independence, domains integrated into bigger proteins still folded themselves into the same familiar shapes and continued to carry out the functions they’d perfected while living on their own. So-called interaction domains, for example, retained the inherent ability to recognize and dock with a “consensus sequence” on another protein. As a consequence, a protein that acquired an interaction domain during the course of evolution inadvertently acquired a new associate as well. Such genetically engineered congeniality was not without risks—there was no law to prevent the same interaction domain from being spliced into several proteins. Conflicts would have been inevitable if not for the fact that in each protein the domain also recognized a unique configuration of amino acids flanking the consensus sequence, a second binding site responsible for choosing the one best match from the pool of potential partners. But even if promiscuity was forbidden, a protein could practice polygamy by adding more interaction domains, allowing it to bond simultaneously with several well-chosen consorts.

As the population of proteins needed to operate increasingly complex organisms grew, interaction domains emerged as an important locus of social control. Partnerships based on these domains organized proteins into teams and networks, directed them to specific locations within the cell and regulated their activity. Portable and self-sufficient, domains facilitated experimentation with new combinations of proteins and graced old warhorses with new flexibility. Yet at the same time they minimized demands on the evolving genome; as molecular biologists Mark Ptashne and Alexander

Gann argue in their book, Genes & Signals, “to evolve increasingly complex biological systems, it may not be necessary to invent many kinds of new gene products. Rather, more sophisticated functions can be achieved, for example, by increasing the number of interactions that any one protein can make, through the reiterated use of simple binding domains, thereby expanding the possibilities for combinatorial association.”

In organisms that needed to direct the behavior of a multitude of cells, interaction domains that “expanded the possibilities for combinatorial association” were the perfect way to expand signaling pathways.

Molecular biologist Tony Pawson, of the Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, calls the intracellular tyrosine kinase Fps the “Rodney Dangerfield of protein kinases.” Just because its cousin Src is built from a gene victimized by the first-known animal tumor virus, Src gets all the respect—or the src gene does anyway. Signaling researchers like Pawson think Fps deserves celebrity status, too. Not just because its gene can also be corrupted by a tumor virus, or because an analysis of what went wrong shed light on how such viruses could turn an ordinary cellular protein into a lethal weapon, but because, in addition, Fps led Pawson to the discovery of one of the most popular interaction domains in eukaryotic signaling pathways.

Pawson discovered that the Fps kinase of healthy cells (encoded by an intact gene, designated “c-fps” to differentiate it from the version damaged by the virus, designated “v-fps”) has two domains: at one end of the protein, a catalytic domain responsible for manipulating phosphate, and at the other end, a domain essential to the protein’s descent into cancerous delinquency. It was this second domain that was targeted by the virus, giving rise to the mutation that transformed c-fps into v-fps. What’s more, Pawson learned, the cancer-causing domain was not peculiar to Fps but was a feature of all

tyrosine kinases that resided in the cytoplasm instead of the plasma membrane—including Src, where it seemed to play a crucial role in making this kinase mind its manners. Intact Src speaks only when spoken to. The rest of the time it’s silent because the critical domain binds to a phosphorylated tyrosine on the other side of the protein, blocking access to the enzyme’s active site. “The kinase is rolled up like a pillbug,” says Pawson. “It bites its own tail, causing a conformational change that inactivates it.” Only when an extracellular signal breaks the bond does Src unwind and start talking about growth and division. Src-gone-bad, on the other hand, literally can’t keep its mouth shut. The tumor virus that mauls it has deleted the phosphorylated tyrosine; without a handhold, the interaction domain cannot hold the protein together, the untethered kinase can babble nonstop, and the poor cell is deluded into thinking it’s tapped into a bottom-less pool of some growth factor. Poor Fps—overshadowed again. Pawson called the dangling interaction domain “SH2,” for “Src-homology 2.”*

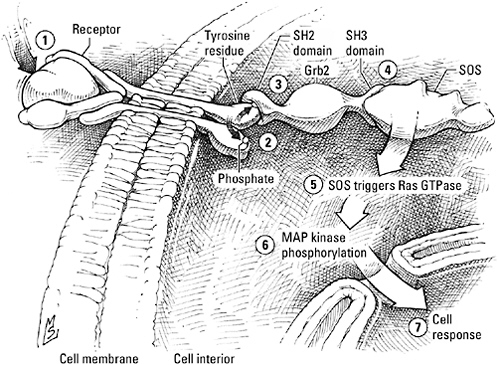

The receptors for many growth factors are themselves tyrosine kinases, with a message for transcription factors that mediate the expression of genes critical to cell proliferation and maturation. Access to these regulatory proteins, sequestered in the cell nucleus, is tightly controlled by a sequence of phosphorylate-and-activate reactions catalyzed by a trio of kinases. Scientists call them “MAP—for ‘mitogen-activated protein’—kinases,” but you could think of them as the Three Fates of Signal Transduction because they control the destiny of so many signals and cells. Playing the role of Clotho, the Initiator, is the MAPKKK, short for MAP kinase kinase kinase. She phosphorylates, and activates, the MAP kinase kinase, or MAPKK. The picture of continuity, what this enzyme receives from one she

gives to the next, bequeathing phosphate and message to her sister the MAP kinase (MAPK), who completes the sequence and intercedes between the world outside the nucleus and the sacred space within.

Naturally, there are relays to connect growth factor receptors and the MAP kinases, pathways that converge on a GTPase known as Ras. And therein lies a problem—the receptor can neither stretch far enough to reach Ras, nor force the eviction of GDP to activate it. The receptor would be reduced to talking to itself if not for the intervention of an adaptor protein and a nucleotide-juggling catalyst, made possible, Pawson discovered, by src-homology interaction domains.

The receptors are a conspiratorial lot; after they bind a growth factor, they pair off and phosphorylate each other’s tyrosine residues. That makes an SH2 domain the perfect confidant. Lucky for the receptors, one is waiting nearby, part of the adaptor protein Grb2; remember it as “grab two,” because that’s what it does: with one hand—the SH2 domain—it clasps a phosphorylated receptor tyrosine residue; with the other—an SH3 interaction domain—it clasps SOS, the protein that masterminds the substitution of GTP for GDP on the dormant Ras GTPase. And when the message arrives at the MAP kinases (after another hand off or two), interaction domains once again keep the conversation going. A scaffolding protein offers a safe haven where MAP kinases can sit down and talk, passing information smoothly from first to last.

Pawson compares interaction domains like SH2 and SH3 that link signaling proteins to the studs on the surface of Lego bricks. Like Lego bricks, proteins fitted with these domains can be snapped together to form sentences of any length. If signaling elements are far apart, adaptor proteins sporting multiple interaction domains can span the distance to connect them, their specificity ensuring that the word order is correct. From an evolutionary point of view, domains are economical as well. If a new demand creates a need to recast a sentence, proteins can be shifted from one signaling pathway

A generic receptor tyrosine kinase. The binding of a signal—a growth factor, for example (1)—triggers the pairbonding of two of these receptors, enabling each to phosphorylate tyrosine residues on the cytoplasmic tail of its partner (2). The Grb2 adaptor protein binds to the phosphorylated tyrosine of the receptor by way of an SH2 interaction domain (3) and to the next protein in the signaling sequence, SOS, by way of an SH3 domain (4). SOS then flips the Ras GTPase switch to the “on” position (5) and activates the MAP kinases (6), which transmit the message to the cell nucleus (7).

to another simply by splicing an interaction domain to create a new connector, rather than waiting around for the evolution of several entirely new proteins. “Interaction domains allow for rapid evolution,” says Pawson. “Say you invented a tyrosine kinase and wanted to use it to signal diverse targets—to interact with or modify maybe 100 different proteins. You would need to invent different ways of doing it for every target, an option that would take lots of evolutionary time. Whereas if you invented an SH2 domain to bind phosphorylated proteins, you would only need to do it once. Then you could take that domain, stick it into a protein, and kerblam!—you can interact with the receptor.”

Leave it to resourceful eukaryotes to find a way to protect a cell’s hearing and get the most out of a receptor protein at the same time. Repetition isn’t any more informative to a liver cell getting its ear talked off by a torrent of adrenaline than it is to a bacterium swimming in sugar, and so the muse that inspired the use of methyl groups to fine-tune the sensitivity of bacterial chemotaxis receptors came up with the idea of using phosphate groups to regulate β-adrenergic receptor sensitivity. Desensitization-by-phosphate can be delegated to one of two kinases: protein kinase A—the same PKA that activates phosphorylase kinase in the “free glucose” campaign—or an enzyme developed specifically for the job, a G protein-coupled receptor kinase, or “GRK,” recruited by the Gβ-Gγ duo in retaliation for their expulsion by Gα. It’s rumor-mongering, protein-style; regardless of which kinase does the deed, the β-adrenergic receptor’s romance with Gs is history.

Worse, a receptor time-out can be a prelude to exile or even execution. GRK continues its meddling by introducing the now unattached and phosphorylated β-receptor to a new suitor, β-arrestin. A scheming rapscallion of a protein, β-arrestin is involved in some shady goings-on with certain membrane proteins—machinations that typically end in the receptor’s abduction; surrounded, then spirited away inside the cell in a pinched-off bleb of membrane. If the receptor’s lucky, it will escape with its life and eventually find its way back to the plasma membrane. Should β-arrestin’s mood turn surly, however, the receptor will be abandoned to certain death in its membrane-bound prison, dissolved by a brew of acidic chemicals and vicious protein-eating enzymes.

But that’s wasteful. Why discard a perfectly serviceable receptor when you can redeploy it, arranging a transfer to another pathway that can still make good use of it? PKA does that—rather than sending the receptors it phosphorylates to the trash bin, it turns them over to the care of another G protein. Seconded to Gi instead of Gs, the β-receptor’s new job description calls for a rendezvous with the

MAP kinases, as if it were a growth factor receptor instead of a hormone receptor.

β-arrestin can direct the receptor to a new career in growth regulation as well, if it’s dressed up as an adaptor. When β-arrestin-the-connector comes to call on a phosphorylated β-adrenergic receptor at the membrane, it comes with three MAP kinases in tow, clinging like burrs to interaction domains built into its topography. Gone is the old preoccupation with catastrophe. Instead of being deported or destroyed, the β-adrenergic receptor gets a new lease on life—and the cell gains another new way to discuss matters of growth and division, without inventing a single new protein.

Architect Christopher Alexander puts it simply: “Patterns,” he notes, “need the context of others to make sense.” Adaptor and scaffolding proteins incorporating versatile interaction domains allowed eukaryotic cells to join protein to protein and pattern to pattern, mixing and matching components to create novel pathways and larger networks. In doing so, they added context without sacrificing clarity, increasing the versatility of signaling proteins while obviating the need for a supercomputer-sized genome.

A LIVING LANGUAGE

Begin your building project, suggests Alexander, with a foundation that doesn’t just sit on the ground but is actually connected to it; sink columns, like tree roots, into the earth below to improve stability and to integrate the building with its natural surroundings. Join column to column at the top with perimeter beams to frame rooms and build a base of support for the next story. Position windows and doorways to take advantage of natural light, highlight a beautiful view, facilitate the flow of traffic between rooms; insert half walls and alcoves to separate activities and afford privacy without isolating people behind closed doors. If possible, break up a single building

into several units—a cluster of small shops or a house and an adjoining cottage, keeping at least half the site as open space. Finally, don’t be selfish and shortsighted—consider your project an opportunity to improve the community at large, locating it to minimize sprawl, preserve green space, and maintain an optimal population density.

According to Alexander, the hierarchal nature of an architectural “pattern language” means that the solutions to the largest design problems—How large should a city be? How can we achieve a balance between urban, suburban, and rural areas? How do we design communities that work toward common goals yet respect diversity?—grow naturally out of the solutions to the smallest—floors and walls, windows and doorways. In such a hierarchical system, every pattern “helps to complete those larger patterns which are ‘above’ it, and is itself completed by those smaller patterns which are ‘below’ it.” A builder need never start entirely from scratch; rather, using a common set of design elements and integrating those elements to form larger patterns, he or she can generate any house, every neighborhood, even an entity as large as a city or a community.

Nature understands this “timeless way of building,” homing in on adaptive solutions to fundamental biological problems, then elaborating on these patterns. As developmental biologists John Gerhart and Marc Kirschner note in their book, Cells, Embryos, and Evolution, “where we most expect to find variation, we find conservation, a lack of change. There is divergence in the accumulated genetic changes … and in protein sequences, but there is conservation in the function and structure of many of the mechanisms of the cell.” Rather than demolish and rebuild, they argue, cells are more likely to recycle, to change the way existing mechanisms are regulated or utilized, rather than the way they work.

Eukaryotic signaling mechanisms exemplify this principle of conservation. Tried and true solutions to the fundamental problems of cell-cell communication, the basic design elements that constitute the language of life, pioneered by simple organisms, were “carried

forward in modern, more complex organisms, elaborated upon but not really changed all that much,” says Kirschner. “So they must have been a very good framework on which to build a very complex organization of a large number of cells, with a lot of cell differentiation and spatial organization.”

Yet paradoxically, signal transduction mechanisms, paragons of conservation, have also been agents of great change. The bridge between the social environment that surrounds the cell and the internal machinery that frames its responses, signaling pathways are respected members of the management team regulating core functions. As a result, changes in “contingency” based on the transfer of responsibility for a conserved function from one signaling pathway to another have become one of the most popular ways for multicellular eukaryotes to experiment without endangering essential processes, going hand in hand with the evolution of these organisms.

G protein-coupled receptors, one of the great linguistic innovations of eukaryotic organisms, demonstrate brilliantly how eukaryotic signaling mechanisms manage to be both conservative and flexible. The receptor protein itself is the epitome of consistency. Like other transmembrane receptors, it comprises an extracellular binding site, a unique configuration of ridges and clefts that correspond, lock-and-key fashion, to the three-dimensional structure of the signal; a midsection submerged in the plasma membrane; and a cytoplasmic segment charged with activating an intracellular signaling relay. It always has the same seven-helical structure. And it always gets its point across by doing a little dance with a G protein, a molecular switch toggled on and off by the binding and breakdown of GTP.

That two-protein two-step introduces plenty of opportunities for improvisation, however. Through the clever use of kinases and adaptors, the β-adrenergic receptor, for example, can be dancing with Gs one minute and then taking a break, preparing to die, or waltzing off with a stranger the next. Adrenaline’s message is usually a call to

arms, but when a sentence typically headed by a growth factor receptor kinase is rewritten this way with a G protein-coupled receptor as its subject, it changes its tune, placing cell growth under the aegis of a new contingency.

The modular construction of G proteins also fosters creativity. Gs, Gi, and all the others, like the receptors they assist, have a common structure: Gα, the anchor; Gβ, the propeller; Gγ, the tail. Within that framework, however, cells have many options. Sixteen different genes code for the α subunit of the tripartite G protein. β subunits are encoded by five. Twelve genes specify γ subunits. By mixing and matching α, β, and γ genes, a cell can create, in theory at least, dozens of different G proteins. And when you add over 800 options for your receptor, “you get a lot of flexibility,” says Al Gilman. “Each cell can go to the genome as if it were going to the local Radio Shack. It can shop for the kind of receptor it needs today, with hundreds to choose from. Then it can go to the counter and start picking a G protein, again, with dozens of possibilities. By combining components, it can build its own custom switchboard, adapted to meet its own individual needs.” Simply by changing receptor-G protein combinations—changing contingencies—an organism can redeploy a conserved process in different types of cells, under different circumstances, or at different times in its life.

Skillful use of mobile interaction domains offered yet another way to conserve patterns while manipulating contingencies. Easily spliced into a new gene, archetypal interaction domains like SH2 and SH3 transformed ordinary proteins into versatile Lego bricks, equipped for jobs in signaling pathways as adaptors or scaffolds. Receptors and kinases continued to do the heavy lifting, while proteins fitted with these interaction domains worried about details like word order, recruiting and assembling signaling components in an approved fashion.

But adaptor and scaffolding proteins did more than prevent verbal anarchy. Domains introduced a new level of complexity, enabling

cells to merge signaling pathways to form networks and redirect components to other partners in alternative pathways. A linguist would say that they made the language of life more productive, meaning that eukaryotic organisms were not restricted to a handful of truisms but could combine signaling proteins in innovative ways as they evolved, generating novel sentences as needed to guide the behavior of large numbers of cells in a wide variety of circumstances. One of the features that distinguish spoken language from the vocalizations of animals or the rigid, formal “languages” of computer science, this flexibility has given multicellular eukaryotes a breathtaking capacity for innovation, a freedom to play with the identity, lifestyle, and spatial organization of cells that has been critical, Gerhart and Kirschner conclude, to the diversity of these organisms.

“Patterns have enormous power and depth; they have the power to create an almost endless variety,” Alexander concludes. Starting with walls and roofs, doors and windows; building up to houses and combining them with offices and stores; adding parks and highways, people can build a city from simple design elements. Similarly, combining signals and receptors, second messengers and G proteins, teams of kinases, adaptors and scaffolds, and linking pathways to create networks, “a few thousand gene products can control the sophisticated behaviors of many different cell types.” Just as the smallest patterns help to complete the larger patterns of neighborhood and city, these smaller molecular patterns help complete complex signaling pathways that, in turn, help complete the even larger patterns of cell and organism.

Doors slam and dogs bark—Jenny and Haley are home from school. Backpacks thump. Someone ruffles through today’s mail; someone else drops a CD player. A quarrel about the ownership of a hat is already taking shape.

“Holla!” I venture.

“Oh my God,” they reply in the tone reserved for my most egre-

gious displays of parental simplemindedness. “NO ONE says that anymore.”

Don’t worry—they will have new words for me to learn. The adoption of words from pop culture, changes in meaning and pronunciation, the relentless influx of slang, the influence of technology and globalization continue unabated, living proof that language is a living entity. It never stops growing or changing, and, if you listen carefully to the younger generation, you learn something new every day.