The Language of Life: How Cells Communicate in Health and Disease (2005)

Chapter: 5 "The Scenario-Buffered Building"

5

“THE SCENARIO-BUFFERED BUILDING”

All buildings are predictions.

All predictions are wrong.

—Stewart Brand, How Buildings Learn

We moved a closet, tore out a vanity, and added a bathtub because the previous owners of our house had installed a dressing room instead of a master bathroom. Across the street, a couple with three growing children bumped out the back wall to extend their kitchen and family room. A more ambitious neighbor raised the roof, added dormers, expanded the garage to include space for three cars, and installed a fence to contain their new puppy. The people on one side just added a deck; those on the other replaced a 12-year-old fence.

“Buildings keep being pushed around by three irresistible forces—technology, money, and fashion,” writes author, editor, and designer Stuart Brand in How Buildings Learn. Houses and office buildings, libraries and schools, grocery stores and gas stations, hotels, restaurants, museums, and concert halls change and grow continuously, because those who live in them, work in them, and visit them change too. Families shrink and grow. A business that once relied on paper goes broadband. Damage from storms, floods, and fires must be repaired. Trends wax and wane: today, a kitchen island is critical; tomorrow, it’s extra closet space.

Unfortunately, most architects, says Brand, prefer to think of their creations as everlasting. The buildings they design resist change. “They’re designed not to adapt; also budgeted and financed not to, constructed not to, administered not to, maintained not to, regulated and taxed not to, even remodeled not to.” Unconventional floor plans, poor uses of space, rigid materials, and inaccessible plumbing or wiring conspire to make even essential updates difficult and costly. In the most defiant cases, extinction may be easier than renovation, and those responsible for deciding the fate of such an architectural dinosaur may well decide to raze and start over again.

Given that change is inevitable, Brand argues that architects should confront the issue head on instead of avoiding it. Buildings remain versatile, he says, when they’re constructed according to a strategy rather than a plan. Strategic or “scenario-based” construction asks those who will use the building to draw up a list of scenarios—ways their circumstances might change in the future—and to examine what the building will have to do to accommodate those developments. Are residents expecting to add to their family? What if a business starts thinking about consolidating divisions, doesn’t land a particular job, can anticipate new government regulations? When the possibility of change is actually factored into the design, a structure remains relevant because it can grow and adapt without breaking the bank or running into an insurmountable roadblock. “A good strategy ensures that, no matter what happens, you always have maneuvering room,” Brand concludes.

Nothing is certain except change. Whether it is a building or a living organism that will be called on to cope, the longest-lived structures are certain to be those best prepared to accommodate bumps in the road. No one would ever accuse the developer who built my neighborhood of being so farsighted—otherwise he would not have placed a ventilation shaft in an interior closet wall. Evolution, however, is a master of scenario-based building. Organisms must be prepared to

adapt or they risk extinction. Since it cannot imagine or foresee the future, however, evolution has instead encouraged mechanisms that confer flexibility and championed processes that allow for experimentation while minimizing the number of fatal mistakes.

The mutability of DNA, the modular nature of proteins, and the co-option of old molecules for new purposes represent some of life’s most successful efforts to accommodate the need to adapt. The power and utility of these mechanisms are nowhere more evident than in the evolution of the design elements of the pattern language that made the advantageous transition to a multicellular lifestyle possible. What’s more, the signaling mechanisms constructed from these patterns were themselves powerful agents for change. Through the use of structural motifs like interaction domains, organisms could revamp the regulation of conserved biochemical functions, link signaling pathways, and control the timing and location of developmental events.

Yet any mechanism that involves alterations to the basic structure of proteins—even a mechanism as light on its feet as adding and subtracting protein domains—requires the luxury of time, time that generations may have, but the individual does not. In addition, the need to adapt has a personal as well as a global dimension. Each individual has his or her own crosses to bear, problems that are irrelevant to anyone else and that are likely to change from day to day. A truly comprehensive scenario-based strategy for life in a capricious environment therefore had to include ways of adapting in the short term as well as over the long term, a way to accommodate change on a minute-by-minute, day-by-day level within the lifetime of each individual, a solution flexible enough that it could be customized to account for personal experience and unique circumstances.

A seemingly insurmountable problem at first glance, but look—that humble bumpkin, E. coli, has its hand up; even it knows the answer. Big-picture evolution has provided the bacterium with enzymes to digest two different sugars. But if the immediate environ-

ment is offering an unfamiliar substance and someone introduces a few drops of lactose-rich fluid on the other side of its flask, what’s the best course of action? Sit in place and wait for a fortuitous mutation to provide a new digestive enzyme able to deal with the strange food? Of course not—the bacterium stops spinning in place and hitches itself over to the sugar it can already digest. Sometime in the future it may change its genes, but today it changes its behavior instead.

Infinitely flexible and quick as the turn of a flagellum, behavior—a response to a perceived stimulus—was evolution’s ultimate coping mechanism, a solution to today’s problems and a way to change again tomorrow if necessary. As is true for so many other biological processes—the development of the embryo, the control of proliferation, the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis, the regulation of critical functions like heart rate and breathing—this integration of perception and response (and eventually emotion and thought as well) could never proceed without communication. In the bacterium, discussion is as simple as a chain of proteins, beginning with a transmembrane receptor and ending with the rotor protein cranking the flagellum. However, in metazoan organisms the adoption of a multicellular lifestyle and a gradual increase in size again demanded communication between cells, over longer and longer distances. Hormones were one solution to this new variation on the problem of long-distance message transmission. But hormonal conversations are promiscuous—it doesn’t matter which islet cell responds to insulin as long as one does—and conversations coordinating stimulus and response had to be precise. After all, if an animal wants to move its right hind leg, the message must get to the right hind leg muscles, not the muscles of the left hind leg, the right front leg, the jaw, the ribcage, or the tail. Challenged to accommodate the twin demands of scope and fidelity, metazoans came up with a new type of cell, the neuron, with a unique shape well suited to the receipt and transmission of messages over vast distances: at

one end, an arbor of short processes, or dendrites, perfect for collecting and integrating information from multiple sources; at the other, a single long process, the axon, that reached out for as long as three yards to contact a faraway partner. To propagate messages from one end of the process to the other, the neuron evolved specialized channel proteins that allow it to manipulate the concentration of charged particles, or ions, and conduct electrical impulses. Much as current flows through a wire, these impulses, known as action potentials, travel down the axon from its origin near the cell body to its terminal.

Axons and ion channels solved the problems posed by distance; a new appliance, developed especially for conversations between neurons, met the need for precision and solved the problem of translating the action potential into a format suitable for cell-cell communication. This structure, the synapse, locked specific neurons into a long-term monogamous relationship. In addition, through the clever use of membranes, actin fibers, and glue, it assembled tools to facilitate the rapid release of chemical signals and sealed off the point of contact, so that neurons could carry on private discussions without worrying that everyone in the neighborhood might eavesdrop on the proceedings. Thanks to these adaptations, cells of the nervous system could use the same type of chemical signaling mechanisms employed elsewhere in the body yet ensure the accuracy essential to the effective, minute-by-minute control of behavior.

In a body of talkative cells, neurons are the most renowned conversationalists. Other tissues discuss the everyday, the practical, or the essential: What should we do about dinner? Am I part of the hand or the head? Could someone please help me patch this cut? The cells that make up our nervous systems describe sunsets, craft poetry, solve equations, remember birthdays, dream. Yet despite their eloquence, they remain true to the fundamental principles of cellular communication. Neurons may sport a college-level vocabulary of perhaps as

many as 100 different signaling molecules (neuroscientists call them “neurotransmitters”), but their conversations utilize the same principles and the same signal-receptor-relay syntax pioneered by the simplest organisms, long before the existence of language, thought, or emotion.

“FAR-SPEAKING” CLOSE UP

The year 1876 was a banner year for communication. In Boston, Alexander Graham Bell filed a patent for an invention capable of “transmitting vocal utterance telegraphically,” the device that would come to be known as the telephone. And in the Spanish city of Zaragoza, an aspiring doctor named Santiago Ramón y Cajal scraped together the remnants of his army payout and made a down payment on a microscope, an investment that would turn out to be priceless to our understanding of neuronal communication.

Cajal had only a rudimentary knowledge of microscopic anatomy or, indeed, of the operation of his new instrument itself; what little he did know came from a brief tenure in the laboratory of his histology professor. He had never actually prepared a specimen for microscopic examination. He could not read German, so he could not consult the leading textbooks. No one at the University of Zaragoza, where he was employed as an anatomy instructor, knew or cared enough about microscopy to teach him. Too inconsequential to merit laboratory space at the university, he was forced to set up a makeshift lab in an attic. Diffident, socially inept, and more sincere than scholarly, his prospects for a career in academia were modest at best.

Yet what Cajal lacked in technical expertise or sophistication, he made up for in dedication and a passionate commitment to self-improvement. As a boy he had wanted to be an artist, an idea that horrified his father, who apprenticed him to a cobbler rather than permit him to take up such a scurrilous profession. Now, as a scientist, the keen eye, inexhaustible patience, and a matchless ability to

re-create on paper what he saw in the microscope were the very traits that made him a sterling anatomist. Gleaning what he could from journals and a few books written in French, he taught himself microscopic technique. To further his study of the literature, he learned German. Applying his newfound skills, he published monographs on the ultrastructure of the epithelium and the muscle fibers of insects and wrote and illustrated a histology textbook. And of all the tissues he observed, described, sketched, or read about in the accounts of other anatomists, none interested him more than the brain.

“In my systematic explorations through the realm of miscroscopic anatomy, there came the turn of the nervous system, that masterpiece of life,” he recalled in his autobiography. Here was a tissue truly worthy of his prodigious talents. “To know the brain,” he wrote, “is equivalent to ascertaining the material course of thought and will.” Yet the difficulties posed by the intricate morphology of nerve cells and the density of their fibers had frustrated the efforts of others to understand the structure and function of the nervous system. That the propagation of nerve impulses involved some sort of electrical activity was clear. But no one could explain how the anatomy, physiology, or arrangement of nerve cells could account for such activity, much less how the brain solved problems or encoded memories. “Nobody could answer this simple question: How is a nervous impulse transmitted from a sensory fiber to a motor one?” Cajal noted.

At the conclusion of his book Minds Behind the Brain, in which he reviews the lives and accomplishments of 18 of the major figures in the history of neuroscience, historian Stanley Finger asks what it was that inspired these individuals to greatness. All, he concludes, had a love of learning, an “addiction” to discovery, a healthy skepticism toward established dogma, an “unwarranted optimism.” But Finger also emphasizes the importance of insight, timing, and the right frame of mind. “The truly great scientists are observant opportunists whose minds are more open than most to anomalies and new

ideas,” men and women, he notes, citing physiologist Sir Charles Sherrington, who have “an intuitive flair for asking the right question” at the right time. Perhaps this explains why neuroscientists still speak of Cajal with reverence. Committed, curious, and foresighted, he was prescient enough to recognize that the time had come to ask the difficult questions about the brain, because it might finally be possible, through the studious application of microscopic techniques, to find answers. Bold enough to ask, he was then astute enough to see. “He treated the microscopic scene as if it were alive,” Sherrington recalled. Over 100 years ago in a country that was then the most backward of scientific backwaters, using no more than a microscope and his own eyes, Santiago Ramón y Cajal discovered or anticipated some of the most fundamental principles of neuroscience, observations that began to explain how the properties of neurons could lead to the behavior of organisms.

When Cajal began his research in the final years of the nineteenth century, neuroscientists were the only members of the scientific community who seemed unaware that everyone else had embraced the “cell theory”—the idea that cells were the building blocks of living tissues—advanced decades earlier by the German biologists Jacob Schleiden and Theodor Schwann. But who could blame them for their intransigence? In contrast to the simple geometric forms of other cells, the neuron, with its mane of dendrites and its taproot of an axon, resembled something that could as easily have come from the garden as a body tissue. Histologists could not even agree where one neuron ended and the other began. Based on the limited amount of detail revealed by the few available dyes, many argued that the processes of each neuron were fused to those of its neighbors, forming an unbroken network, or reticulum, rather than a conventional tissue composed of discrete cells.

In 1887, Cajal was summoned to Madrid to administer the examinations for doctoral candidates in descriptive anatomy. During

his stay, a young neurologist, Don Luis Simarro, showed Cajal some slides of the brain stained with a new technique he had learned in Paris. Building on the well-known reaction of silver salts to light that had inspired the development of photography, an Italian physician, Camillo Golgi, had treated sections of brain tissue with a solution of silver nitrate, hoping to capture more detailed images of neurons. He was successful beyond anyone’s imagination. For reasons that are still obscure, the silver stain impregnated a tiny proportion of neurons (somewhere between 1 and 3 percent); in these neurons, however, the stain permeated the entire arbor of processes, revealing the intricate structure of the whole neuron as clearly as if it had been drawn by an artist in pen and ink. Using this reazione near, or “black reaction,” Cajal learned, Golgi had been able to describe in vivid detail the architecture of neurons in several brain regions, including the cerebellum and the olfactory bulb.

A few iconoclasts had already begun to question the reticular theory, to criticize the possibility that of all the body tissues only the brain and spinal cord were not made up of discrete cells. Surely Golgi’s stain would shed light on the matter, everyone thought. But Golgi was the most ardent reticularist of all. Anyone looking at his slides could see how the processes of these cells crossed, overlapped, intertwined—proof, he insisted, that they must be linked seamlessly in a brainwide web.

The silver stain was as capricious as it was beautiful, Simarro cautioned Cajal. Even Golgi himself acknowledged that it was time-consuming and inconsistent, that one experiment could produce the stunning images Cajal had admired while the next failed utterly. But Cajal recognized that in the “black reaction” he had found the “tool of revelation” that would allow him to visualize the brain in the detail necessary to begin unraveling its secrets. He had ideas for improving the technique. And he had an idea why it had still not resolved the question of whether neurons were individual cells or a reticulum.

The problem, as Cajal saw it, was that in the adult brain it was impossible to see the forest for the trees:

Two methods come to mind for investigating adequately the true form of the elements in this inextricable thicket. The most natural and simple apparently, but really the most difficult, consists of exploring the full-grown forest intrepidly, clearing the ground of shrubs and parasitic plants, and eventually isolating each species of tree, as well as from its parasites as from its relatives … the second path open to reason is what, in embryological terms, is designated the ontogenetic or embryological method. Since the full-grown forest turns out to be impenetrable and undefinable, why not revert to the study of the young wood, in the nursery stage, as we might say?

Using a modified, more dependable version of Golgi’s silver stain, Cajal probed the “young wood” in the brains of the immature and found that if he applied the technique before the myelin sheath formed, “the nerve cells, which are still relatively small, stand out complete in each section; the terminal ramifications of the axis cylinder are depicted with the utmost clearness and perfectly free.” In the cerebellum he not only observed the plump bodies of Purkinje cells described by earlier investigators but also described axons that split and wove baskets around them, as well as axons that climbed the cell body and insinuated themselves throughout the dendritic arbor like “ivy or lianas to the trunks of trees.” He observed long processes of sensory neurons coursing into the brain from the retina and olfactory bulb. He saw the elegant pyramidal cells of the cerebral cortex, the chunky interneurons of the spinal cord. Nowhere did he see nerve cells fused together in a reticulum.

From his observations, Cajal drew two historic conclusions. First, the brain, like other tissues, was made up of individual cells, which stood shoulder to shoulder with each other but did not fuse. Second, the arrangement of neurons and the orientation of their processes suggested that the neuron was a one-way street. Sensory nerves, for example, had their dendrites in the periphery, while the tips of their axons were located in the brain—a layout that made perfect sense if

the dendritic arbor took in information. The dendrites of motor neurons, on the other hand, were located in the brain or the spinal cord, and their axons terminated on the muscles, out in the body, implying that the axon forwarded information. A neuron, in other words, listened with its dendrites and, if it chose to send its own message in turn, spoke via an inpulse (the action potential) that traveled away from the cell body down the axon.

Sir Charles Sherrington was greatly impressed with the “neuron doctrine” and Cajal’s “principle of dynamic polarization”—so impressed, in fact, that he wrangled a speaking engagement at the Royal Society and insisted his Spanish colleague stay at his house afterward.* What’s more, Sherrington recognized that if neurons were not joined together and if “the nerve-circuits are valved,” there must be something special about the point of contact, some structural feature or mechanism that enabled a signal to cross the gap between axon to dendrite. “In view of the probable importance physiologically of this mode of nexus between neurone and neurone,” Sherrington argued, “it is convenient to have a term for it.” He called the connection the “synapse,” from the Greek meaning “to clasp.”

Even the sharp eyes of a master like Cajal could not provide any further detail: the synapse was a gap so narrow it was beyond the resolution of any light microscope. An eyewitness account of the architecture of the synapse—indisputable proof for any diehard who still harbored doubts about the neuron doctrine—had to wait until the 1950s, when neurobiology saw the introduction of a tool even more powerful than silver: the electron microscope.

Like all architectural innovations, the neural synapse evolved to solve problems, in this case the problems associated with distance, preci-

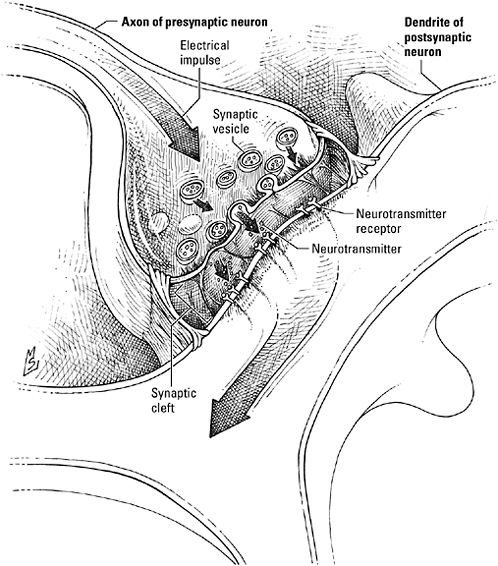

sion, one-way transmission, and diffusible chemical messengers. Electron microscopic studies of the ultrastructure of the synapse, along with the identification of proteins specific to the presynaptic (the axon) and postsynaptic (the receptive dendrite) membranes, have revealed that this specialized junction incorporates design elements and construction materials developed to address each of these problems. Some, such as receptors that double as ion channels, are distinctly neuronal. Others—specialized adhesive proteins tailor-made to reinforce connections between cells, for example—are adaptations of tools and techniques that metazoans have been working on since the invention of the epithelium, when they first began joining cell to cell in an organized fashion.

By definition the neural synapse is asymmetric. On the presynaptic side the axon terminal is specialized to meet the challenges of directed secretion. Of course, the process of secretion itself is not peculiar to neurons (hormones and digestive enzymes are other examples of substances forcibly extruded by the cells that make them); in all secretory cells the product to be exported is packaged in membrane-bound vesicles, which dock at, then fuse with, the plasma membrane, disgorging their contents into the extracellular space in the process. But the neuron faces a problem unknown to the cells of the gut or the adrenal gland. Proteins, including membrane proteins needed to construct secretory vesicles, are made in the cell body, far from the axon terminal, which may be up to three yards away. An intra-axonal “railway” of microtubules is available to transport these proteins down the axon, but if the presynaptic terminal had to wait for the train every time it needed to get a message across the synapse, moving an arm or a leg might take weeks. To get conversation up to realistic speed, neurons have installed a revolving secretory apparatus at the synapse. Instead of waiting for new vesicles to travel the length of the axon, they recycle the ones they already have, refashioning them from the plasma membrane and refilling them locally. Fully loaded vesicles are then kept at the ready, concentrated at release

The neural synapse.

sites within the so-called active zone, which looks out directly on the receptors waiting across the cleft. Some vesicles have already redocked at the plasma membrane before the action potential ever arrives; a few have even begun to fuse, poised to expel their neurotransmitter at a moment’s notice. Behind these first responders, backup vesicles wait in a grid anchored to the presynaptic membrane, like racehorses

pawing in the starting gate. And behind them still more vesicles are held in reserve, tethered to actin fibers in the cytoskeleton and prepared to drop into the grid should a volley of impulses deplete the pool concentrated at the active zone.

The buzzers that spring the loaded vesicles are voltage-sensitive proteins built to channel calcium ions. Planted throughout the active zone, the doors of these calcium channels are kept tightly closed while the neuron is quiescent. The arrival of an action potential flings the doors open, flooding the terminal with calcium. “Go!” it shouts. In response, the vesicles discharge their payload, and the liberated neurotransmitter seeps across the synaptic cleft into the waiting hands of the receptors on the postsynaptic neuron.

Even if you’re not a histologist, you’d have no trouble spotting the postsynaptic membrane in an electron micrograph—it’s the one underlined in black. Actually a tightly woven matrix of protein, this postsynaptic density, as it’s called, locks neurotransmitter receptors in place directly opposite the secretory apparatus of the presynaptic neuron. Some it even arranges like flowers in a centerpiece. For example, receptors for the amino acid neurotransmitter glutamate, which come in two varieties, are organized with those subtitled “NMDA” (because of their affinity for the compound N-methyl-D-aspartate) in the center, surrounded by the type known as “AMPA” (for alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-isoxazole-4-proprionic acid, one instance where an acronym is absolutely, totally justified). In addition to receptors, the postsynaptic density contains proteins that participate in signaling relays (kinases, for example), proteins that regulate the internalization and recycling of receptors, and proteins that connect the array to the internal scaffolding of the dendrite.

Holding the entire construct together are adhesion molecules, membrane proteins that reach across the gap in both directions to clasp axon to dendrite like the hooks and loops of Velcro. Within the confines of the synapse, those called neurexins, located on the presynaptic terminal, bind neuroligins, their “receptors,” on the postsynaptic terminal. Others, known as cadherins, flank the synapse; their

intracellular domains bind to catenins, which anchor them to the cytoskeleton. Adhesion molecules do more than maintain connections and align neurons, however. Available in a wide range of isoforms (variants of the same protein made by splicing mRNA fragments in different ways), the cadherins, in particular, bind one another with a specificity as selective as any signal-receptor pair. During development, neurons rely on these interactions to assist them in identifying an appropriate partner. In the adult brain, adhesive interactions between the “parasynaptic” cadherins form a seal around the synapse that ensures privacy and precision.

The word “telephone” means “far speaking,” an ideal term for a device that could allow a person to speak directly with another across town, across the country, or on the other side of the world. Neurons, that felicitous invention of talkative metazoans, are also “far-speaking” devices. With their axons traversing the brain and coursing through the spinal cord, neurons allow one part of the nervous system to talk directly to another, no matter how far apart they are. And where axon and dendrite meet, the architectural features of the synapse direct the release of neurotransmitter, focus the attention of receptors, maximize precision, and guarantee clear, high-fidelity conversations.

DRIVERS WANTED

Ross Harrison was the only biologist to win a Nobel Prize and have nothing to show for it—he was selected by the Nobel committee in 1917, but because of the World War, the prize in physiology or medicine that year was not actually awarded. So let’s give Harrison his due. He was, after all, the man who invented tissue culture, and he used it to answer a critical question about the development of the nervous system: How did peripheral nerves, such those innervating the muscles, body organs such as the heart, or sense organs in the skin, connect with their targets?

It was a problem that had also intrigued the master. Cajal’s con-

temporary Viktor Hensen claimed that the neuron and peripheral sense organ began as a single cell that stretched from brain to periphery and then divided. Cajal and a number of other prominent anatomists disagreed. Neuron and target developed independently, they argued, and the axon of the nerve cell grew outward to meet the organ destined to be its partner. The resolution of his silver stain had even allowed Cajal to visualize the uncommitted tips of young axons and to track their progress in serial sections prepared over the course of embryonic development.

Beautiful and detailed as they were, Cajal’s slides were only snapshots, however. Harrison’s method of culturing living tissue outside the embryo allowed him to actually visualize the movement of axons in real time. To create a micronursery, Harrison dribbled a ring of wax on a microscope slide. He placed a drop of lymphatic fluid on the surface of a glass cover slip—a substitute for the fluid milieu of the embryo. Then he submerged a tiny piece of tissue excised from a frog embryo in the drop and inverted the cover slip over the ring of wax. The wax sealed out microorganisms and prevented dehydration, while the cover slip permitted a clear view of the goings-on within the “hanging drop.” Harrison observed that cultured explants of presumptive epidermis or mesoderm—precursors of target organs—made no attempt to explore their new environment. However, when he examined explants from the neural tube in tissue culture, Harrison saw young axons poking out of the explant and growing toward the edges of the drop, as if searching for their missing targets.

But how did they ever find their way? Perhaps they navigated like most men, to whom maps are an impediment and asking directions an insult—they set off in the general direction confident they’ll recognize their destination when they get there. Or perhaps evolution put a wife in every axon, an instinct unafraid to consult a map. Cajal favored the latter. The free ending of the axon, he noted, “appeared as a concentration of protoplasm of conical form,” a structure he called a “growth cone.” He imagined this growth cone to be

an inquisitive, groping structure, a sense organ “endowed with amoeboid movements” and possessing “an exquisite chemical sensitivity.” All this prying and probing enabled the growth cone to “read” chemical signposts marking the path to the target; as it crawled from marker to marker, the little navigator hauled the axon along behind like a length of cable.

Cajal was correct. Homing axons are not gifted with a wiring diagram, written in the genes—a solution to the routing problem that would have required a supercomputer-sized genome. Nor do they have an internal compass. But they have not been abandoned to wander in the dark either. Every millimeter of the way the young axons can rely on chemical signals to chart their course, direct them around corners, and tell them when to steer clear, steadily and accurately guiding them to their posts.

“Philadelphia—45 miles.” In my mind the journey from my house in the suburbs to the University of Pennsylvania, where I’ll be using the medical library, can be broken down into several steps. First, there’s I-95, leading into the city. Then I have to navigate the expressway through the city, the fearsome left-hand merge onto I-76, and the turn onto South Street. Once I’m in the university neighborhood, I’ll head for my favorite parking garage and hope it’s not full. Finally, I’ll ease the car into a parking space—or bully a student into yielding one on the street.

En route, I’ll be relying on dozens of road signs to show me the way. Lines on the pavement will mark out lanes, the median, and the shoulder of the road. Overhead and on either side are signs that tell me “Go here”: the green exit signs for the Vine Street Expressway and I-76, street signs for Chestnut Street and Walnut Street, and the white sign at the entrance to the parking garage. And there are signs that warn me not to go in certain directions as well, such as “Wrong Way—Do Not Enter,” posted to keep people trying to get on the highway from turning onto the off-ramp, and the one-way signs that are the bane of city driving.

Growing axons en route to their targets travel in stages, too, and they’ll also be on the lookout for road signs to help them make decisions as they go. Some, like the white and yellow lines that indicate my lane, will define their road. Others will tell them when to turn as well as whether to go right or left, the equivalent of exit or street signs. Still others will block their progress: Do Not Enter signs, or Stop signs planted at their targets to let them know that they should park, fold up their growth cones, and set about building a synapse.

The developing spinal cord is an example of a master cartographer. When we last saw this part of the nervous system, young neurons had scarcely begun to think of the long journey ahead. Just born, they were still sorting out the details of their identity. Now they’re finally ready to head out: motor neurons to the muscles; interneurons to the neighbors; and a third group, known as commissural neurons, to partners on the opposite side of the spinal cord. These cells, which will coordinate the left and right sides of the body when they’re fully grown, have the hardest route, featuring an especially tricky turn. Neurons starting out on the left, for example, first grow down the wall of the spinal cord toward the floor plate. But before they hit bottom, they’ll have to make a 90-degree turn, cross the midline, and continue growing on the right side of the cord, without accidentally wandering back to the left.

Culture a piece of spinal cord with a bit of floor plate and commissural axons grow out of the cord explant and toward the floor plate as if drawn by invisible magnets. The big attraction is actually a

A road map for neural development. Growing axons, like drivers, depend on a variety of road signs to keep them on course as they move toward their destinations. A, the adhesion proteins known as laminins, which bind to integrin receptors on axonal growth cones, act as “lane markers” to keep axons on the correct path without straying. B, chemoattractants, exemplified by the netrins that direct commissural neurons in the spinal cord to the midline, are the neural equivalent of exit or street signs. C, signals like the ephrins post Do Not Enter signs to keep axons away from off-limit areas.

pair of signaling proteins called “netrins,” which direct the growth cone via receptors that mimic the receptor tyrosine kinases favored by growth factors, engaging an adaptor protein studded with SH2 and SH3 domains to activate a GTPase. In the living embryo, netrins are “go here” signals; like highway exit signs, they point commissural axons toward the midline. Netrin-1 is secreted by the floor plate cells. Netrin-2 is spoken by cells just above the floor plate. The ventral-to-dorsal gradient of netrin-2 lures axons into the second gradient of netrin-1, which guides them downward and inward, toward the center of the floor plate.

Anyone who’s still confused can flip back a page and consult two markers that ought to be familiar from the previous stage of development—Sonic hedgehog and the bone morphogenetic proteins. Already loitering around the floor plate after it’s finished the task of patterning the ventral spinal cord, it’s understandable that Sonic hedgehog would take up a new career as a guide to migrating axons, supplementing the efforts of the netrins. Overhead, BMPs have nothing to do either; they might as well busy themselves pushing any errant axons away from the dorsal half of the spinal cord. “Thus, together, these findings provide a pleasing result,” write developmental neurobiologists Frédéric Charron, Marc Tessier-Lavigne, and colleagues. “Shh and BMPs, which initially cooperate to pattern cell types along the dorsoventral axis … later appear to cooperate to guide commissural axons … the attractant is at the ventral midline, providing a pull, and the repellant is at the dorsal midline, providing a push.”

Once they reach the midline, whether they’re drawn by netrins, pulled by Sonic hedgehog, or shoved southward by BMPs, the axons find a carpet of adhesion molecules rolled out for them across the midline. Receptors on the growth cones allow them to tiptoe from one side of the cord to the other along this runner. Then, before they can change their minds or wander off course, they lose their taste for adhesive proteins. As a result, they cannot go back the way they

came; that road’s blocked, and they’re forced to follow a new path in their new location.

At the other end of the nervous system, you may encounter a clutch of axons crowding the entrance ramp leading from the retina into the brain. If you had been here a few hours earlier, you might have caught a road crew of glial cells, those occupants of the nervous system that didn’t make the final cut to be neurons, painting fresh lines to mark the highway from eye to brain. Barred from using white or yellow paint, however, they turned to the adhesive protein laminin, squirting a stripe of this indicator directly into the “skin” of the extracellular matrix that coats their surfaces. Receptors in the growth cones of retinal axons adhere to the laminin in the matrix, much as your finger might stick momentarily to the tacky surface of not-quite-dry paint. Laminin is no ordinary glue, however. This adhesive is also a signal, and laminin receptors, known formally as integrins, relay this signal to the cytoskeleton (as well as to intracellular signal transduction relays).

Look closely at integrins and you’ll note an uncanny resemblance to G proteins. A composite of two subunits, α and β, the binding domain of an integrin contains a propeller similar to Gβ, and an I/A domain comparable to Gα. When binding a laminin, the propeller and the I/A domain separate (just as Gα and Gβγ dissociate when stimulated by a G protein–coupled receptor), activating the integrin and dispatching a signal to the cytoskeleton via a short tail that spans the membrane; in the case of the neurons waiting to leave the retina, the message reads: “You’re on the right path.” The fibrous cytoskeletal proteins tighten, and the growth cone crawls along the laminin-coated surface, translating a chemical signal into movement. Once the axons arrive at their target in the brain—the optic tectum, a way station for visual information—the line of laminin that got them there fades. And the glia don’t bother to replace the laminin because the axons wouldn’t see it anyway; they’ve stopped making the integrins that allow them to read it.

The plan then calls for retinal axons to select partners according to their site of origin in the retina, mapping out a faithful representation of the visual field. Axons originating in the temporal portion of the retina (that closest to the side of your head) seek and synapse with neurons in the anterior portion of the tectum, while neurons originating in the nasal portion of the retina (near the bridge of your nose) home to the posterior tectum. To ensure that temporal axons stay on their side of the optic tectum and find anterior partners, posterior tectal neurons have posted “Do Not Enter” signs—signs that can only be read by the temporal axon growth cones. Like Delta (of Notch and Delta fame), these signals, ephrin A2 and A5, are intrinsically well suited to the delicate task of patterning at close quarters, for they remain membrane bound and are never secreted. Feisty ephrins also talk back. After they bind to their receptors, they don’t just sit there or fall apart—they post a letter to themselves as well, triggering a signaling relay that travels backwards into the signaling cell.

Contact between a misguided temporal axon and a posterior tectal cell is as toxic as two young children in the back seat of a car. “MOMMM! She touched me!” the axon whines and then retreats to the ephrin-free anterior tectum where its ephrin, or “Eph” receptors can avoid contact with the offending signal. “Ewww, cooties!” retort neurons of the posterior tectum when their ephrin signaling molecules alert them to an out-of-place axon, and they retaliate in some way that scientists haven’t quite figured out but suspect may be a change in adhesive properties. The axons of neurons in the nasal portion of the retina, on the other hand, are like good-natured siblings who get along with everyone. Then again, it’s easy to overlook insults when you’re deaf. Nasal axons have fewer Eph receptors than their temporal counterparts, so they never hear the posterior tectum’s ephrin insults. They sail right by the barricade, each on its way to a lifetime partnership.

A blue and white North American moving van pulls up and begins unloading couches, chairs, tables, beds, boxes of dishes and boxes of books, a cedar play set, three televisions, and a plastic dog house. The new neighbors are moving in, and like other experienced suburban home owners, they have arrived with all the baggage and modern appliances needed to get their home up and running. The axon that’s just completed its journey and the dendrite it has selected as a partner also pull up to the curb fully prepared to begin the task of setting up a new synapse. Before they even trade a handshake, the axon has already begun to assemble vesicles and is putting the final touches on its secretory apparatus, while the dendrite already has begun to stock up on receptors. Both are dying to strike up a conversation. But the words they’ll trade now will not be anything like the gene-manipulating signals that made them neurons in the first place.

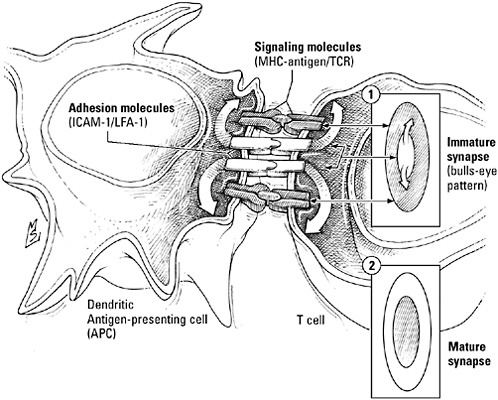

The signals that control the formation of synapses, says Joshua Sanes, a neurobiologist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, “are organizers, not inducers.” He explains: “Inducers make the cell into something it didn’t used to be by turning on a lot of genes. During synapse formation, proteins that neurons have already made—the docking mechanism for vesicles or calcium channels, for example—are being put together.” What’s more, Sanes notes, the assembly of synaptic proteins doesn’t really require formal neurotransmission, although the two neurons certainly talk to each other during the process. Once the two neurons pair off, the presynaptic neuron will install the secretory apparatus it has constructed, stock it with a supply of vesicles, and begin releasing little trial balloons of neurotransmitter. The postsynaptic neuron will follow its example, gathering receptors into clusters and fixing them in place with the protein matrix of the postsynaptic density. Finally, adhesion molecules will bind the whole structure together, securing the connection and sealing it off to keep neurotransmitters in and distractions out.

Because the connections between nerves and muscles are easier

to observe and manipulate during development, researchers who study synapse formation, like Joshua Sanes, have come to rely on the neuromuscular junction as a model system. In this case, the presynaptic element is the motor neuron, which will use acetylcholine as its neurotransmitter, and has a branching axon looking to form synapses with dozens or even hundreds of different muscle fibers. The postsynaptic element is the immature muscle fiber, or myotube. As the synapse matures, the surface of the muscle will wrinkle into a series of so-called junctional folds; the acetylcholine receptors cluster at the tops of these folds. Between axon and muscle, in contrast to neuron-neuron synapses, is a thin band of matrix proteins, the basal lamina, which runs through the middle of the synaptic cleft like a line drawn to emphasize the separation of the two elements.

The formation of the neuromuscular junction is initiated by the arrival of a motor neuron axon eager to latch on to a myotube and take charge of its life. Young myotubes have already begun making acetylcholine receptors. But without someone to explain how to gather the receptors into clusters, each has simply inserted them randomly into its membrane. With a word—agrin, a large protein encrusted with carbohydrate residues—the axon herds those receptors into the synapse and secures them with a cytoskeletal protein called rapsyn. Motor axons like their receptor clusters to be really generous, so in addition to agrin they release a signal, neuregulin, that binds to a receptor tyrosine kinase on the muscle fiber and calls for more acetylcholine receptors to fill out each cluster. Finally, when the big day arrives and the motor neuron starts firing action potentials in earnest, the acetylcholine it lobs at the muscle fibers shuts down any illicit receptor making or gathering.

The muscle fiber and the intervening basal lamina have had a few choice words for the axon as well. Some scientists say they’ve overheard cadherins, similar to those that Velcro neuron to neuron at central nervous system synapses, telling motor axon terminals to ramp up the supply of synaptic vesicles and reinforce the protein

scaffolding. Laminin, a constituent of (surprise, surprise) the basal lamina, is suspected of exhorting them to grow up and start releasing neurotransmitter. And to get axons in tip-top shape for neurotransmission, some recent studies suggest that muscles feed them a protein shake containing growth and survival factors.

Synapses in the central nervous system are made in much the same way, says Sanes, although far less is known about the identity of the organizational signals. For example, when immature neurons are maintained in tissue culture, axon terminals stimulate the clustering of receptors for glutamate and the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) in much the same way motor axons stimulate the clustering of acetylcholine receptors in muscle fibers. In the brain, however, many neurons must also perform skilled feats of receptor distribution, for their dendrites may make synapses with numerous axons, each of which uses a different neurotransmitter. Scientists don’t know what these axons say to engineer such complex receptor patterns. But they do know that neurons in the central nervous system have a protein on the postsynaptic side much like the rapsyn in myotubes, which helps stabilize the clusters once the mystery signals collect them. Conversely, on the presynaptic side, a recent study has demonstrated that the adhesion molecule neuroligin tells axon terminals it’s time to assemble synaptic vesicles.

When neuronal migration and synapse formation are done, the young brain can feel a real sense of accomplishment—it’s wired about 1015 individual connections. If anything, it has done its job a little too well. While obsessing about precision, it overlooked capacity; busy planning itineraries, it has overbooked most destinations. Many muscle fibers, for example, have been innervated by not just one axon, but several. The nervous system that has had too much of everything all along—precursors, neurons—now has too many synapses as well. The extras must be eliminated, all but one axon withdrawn. That, says Joshua Sanes, marks the beginning of a lifetime of adaptation in which alterations to synapses play a pivotal role. “The

initial contacts are the hardwiring,” he explains. “Synapse elimination is the refinement. And it probably happens in the central nervous system as well. We’re used to thinking of this incredible specificity. The final pattern does come partly from hardwiring, one on one, but also partly by rearrangement.”

A surfeit of synapses may be a fail-safe, a way of ensuring no part of the wiring pattern is accidentally left out—“like shooting at a target with a machine gun, rather than a pistol,” as Sanes puts it. Or it may be a matter of survival of the fittest: from the pool of synapses the brain selects the “best” ones. But there’s also a third explanation, Sanes adds—the extra synapses offer a way to sculpt the young brain according to its experiences. “The best way to make patterns may be to selectively eliminate the wrong possibilities. In other words, you could build only the proper synapses. Or you could build extras, stabilize the proper ones, and let the others fall away.”

Neural synapse formation can take place in the complete absence of neural activity. Synapse selection and maintenance cannot. “Activity is essential for growth and maturation,” concludes Sanes. “Experience is activity, and so experience is what shapes synapses and our nervous systems.”

SPEAK, MEMORY

A whisper of leaves, a sudden shadow, an agile duck-and-scramble under a log. A quick response has just averted certain death in the clutches of a hungry predator, but what good is such an accomplishment in the long run unless the experience can be retained for future use? A quarter-mile away my dogs and I wander along the creek bank, enjoying a languid summer afternoon. We don’t have to worry about predators. But this daydream could become an ordeal if I don’t recognize the poison ivy growing along the path or can’t find my way back to my car.

An organism’s ability to mount effective, appropriate, and adap-

tive responses depends on the brain’s skill at differentiating the essential from the irrelevant and applying lessons learned in the past to the present. Sifting through what is seen, heard, felt, read, or imagined through the filter of experience, it must correctly identify a bewildering variety of people, places, things, and events and assign each a meaning. That rustle means “Danger! Run!” A trio of shiny leaves means “avoid this plant.” The bend in the creek and a map in my head tell me how to retrace my steps to the parking lot.

The brain isn’t born with a recording of a fox’s footfall, the knowledge that certain plants irritate the skin, or a map of the nearest park. As Steven Hyman, Harvard provost and former director of the National Institute of Mental Health has put it, “Organisms need to be able to make predictions about where danger lies, where good, life-enhancing things lie. Some things—like the rewarding nature of sex—are hard wired. But there are a lot of things that evolution could not know about ahead of time.”

Behavior evolved to facilitate change. But the nervous system that coordinates behavior also includes mechanisms to facilitate continuity, to enable considered responses as well as allowing for novel ones. Taking advantage of the ability to link the binding of chemical signals to changes in proteins and gene expression afforded by the syntax of cellular language, neurons have exploited synaptic transmission to devise methods of generating connections between behaviors and outcomes—learning—and to store important associations for future reference—memory.

No doubt about it, the tree had to come down. It had passed the point of simple encroachment and annexed an entire corner of the yard, adding a swath of the deck for good measure. It swallowed the sun and regurgitated a mound of sickly yellow needles in its stead. The new neighbors contemplated the behemoth for two weeks, then called a landscaping service to cut it down.

Out with the old and in with the new—swings, the sandbox, the

wading pool. Grass sprouted. Weeds invaded. Even the climbing roses on our side of the fence, anesthetized for so long by the shadow of pine boughs, woke up and turned somersaults over the fence rail, tossing sprays of blooms as they went.

During development and throughout life, experience, that tireless gardener, tends the synapses of the brain, taking away a little here, adding a little there. “Use it or lose it” is the order of the day. Neglected, underutilized connections grow weak and are pruned. Active synapses grow stronger. Their participation in a clever association or a beneficial response is noted and encouraged. Used and reused, they sprout a memory—literally. Experiences this significant cannot be entrusted to some transient medium; to preserve them for months or years to come, they are recorded in the actual physical structure of the neuron.

The climbing roses here are the dendrites—or to be more specific, the knobs known as spines. Shaped like tiny clubs, with a bulbous head seated on top of a narrow shaft, spines are hot spots for synapses, particularly so-called excitatory synapses, in which the word spoken by the axon terminal stimulates the postsynaptic cell to action. The precursors of spines are mobile, actin-rich fingers, or filopodia, that grasp at incoming axon terminals in the earliest stages of synapse formation. But spines retain their penchant for shape shifting long after the building is over, making them a malleable medium, easily sculpted or redistributed.

“Action!” at an excitatory synapse, as noted earlier, is translated “glutamate.” Released by the presynaptic partner, it can choose between two types of glutamate receptor across the cleft, both signal-gated ion channels fashioned specifically for the speedy propagation of important messages. AMPA receptors conduct sodium and potassium ions and are incorrigible chatterboxes. NMDA receptors conduct calcium as well as sodium and potassium. Strong, silent types, they can’t talk much of the time even if they want to because their mouths are usually plugged with a fat magnesium ion. Only a com-

bination of glutamate and a conversation animated enough to activate, or depolarize, the postsynaptic cell will expel the magnesium, freeing the NMDA receptor to talk calcium to listeners inside the cell.

Cyclic AMP has the glamorous history, but no second messenger is more hard working or widespread than calcium. Within the cell, changes in calcium concentration triggered by events like the opening of NMDA receptor channels are detected and relayed to other signaling proteins by dedicated calcium-binding proteins. The most ubiquitous of these go-betweens, found in all eukaryotic cells, is called calmodulin. Calcium turns calmodulin into a social butterfly. Content to stretch out languidly to its full length when calcium isn’t around, calmodulin grabs the nearest target protein in a bear hug when calcium is present; among the favorite objects of its affection are a family of kinases that add phosphate groups to the amino acids serine or threonine, known collectively as “calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinases”—CAM kinases for short. An active CAM kinase is memory’s best friend. Thanks to its eagerness to gossip with other signaling proteins, neuronal activity can be translated into long-lasting changes in the structure and function of spines and synapses.

Even a slug can learn. With a nervous system of only 20,000 neurons, the giant marine snail, Aplysia californica, can be trained to respond to an innocuous stimulus as if it was a life-threatening event. Following a brief electric shock to its tail, the slightest touch to the overlying mantle or the siphon causes the animal to flinch and retract its gill. Neurobiologists call this exaggerated defensive reaction “sensitization,” and its duration varies according to the intensity of the noxious stimulus. The effect of a single shock lasts only a few minutes. A series of shocks, however, elicits vigorous reactions to touch for days or even weeks.

Aplysia isn’t a rocket scientist, but for neurobiologist Eric Kandel,

corecipient of the 2000 Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology for his work on the biological basis of memory, that was the appeal of its simple accomplishments. When Kandel began studying the neurobiology of learning and memory in the 1970s, trying to approach the problem by studying the sophisticated mammalian brain was as impossible as searching for the proverbial needle in a haystack. What was needed instead, he recalls, was a “radically reductionist approach” that focused on the acquisition of a simple task in a creature with a less intricate nervous system. By doing so, Kandel believed he could identify fundamental neural mechanisms common to memory storage in all nervous systems. “When I went to Aplysia I had a sense that there was a universality to biological systems,” he observes. Indeed, his studies of simple learning paradigms revealed two basic features of memory common to both this simple invertebrate and creatures like mammals, capable of mastering more difficult tasks: first, that all forms of learning, whether they involve simple associations or the retention of facts and events, occur in two phases, one transient, or short-term, and the other more enduring; second, that short-term memory requires only modifications to existing proteins, while long-term memory storage entails the synthesis of new proteins and modifications to the physical architecture of the synapse.

The synaptic changes associated with short-term sensitization to an electric shock are a metazoan adaptation of an idea known even to bacteria: a reminder can be as simple as a Post-it note slapped on a protein. To “remember” the concentration of a nutrient from one twiddle or tumble to the next, E. coli adds or subtracts methyl groups to and from its chemotaxis receptors. In the slug, news of an electric shock to the tail is transmitted from a sensory neuron in the tail to an excitatory interneuron, which in turn synapses on a sensory neuron in the siphon and regulates its activity. The exchange between the interneuron and the siphon sensory neuron results in the activation of protein kinase A. The kinase, in turn, phosphorylates calcium channels and proteins of the secretory apparatus, enabling the

sensory neuron to release more neurotransmitter—the alarm signal that activates motor neurons responsible for gill withdrawal.

Post-it notes are easily lost. Important information—like repeated electric shocks—merits a more enduring sort of record keeping. In this case, recurrent activation of the interneuron leads to persistent activation of protein kinase A. It’s so annoyed, in fact, it complains to the MAP kinase. “You’re right,” MAP kinase agrees, “the higher-ups need to know about this,” and so it scuttles off to the nucleus and pours its heart out to the transcription factor CREB. CREB talks to some genes, the genes take action, and the first thing you know, new proteins are on their way to the sensory neuron terminal, proteins that will physically reinforce this obviously important connection by stimulating the addition of new synapses.

So what if a sea slug can learn to avoid live wires, you may be thinking. A human being needs to remember more important things—the names of co-workers, how to log on to the new office computer system, how to care for a newborn baby, the dates and battles on tomorrow’s history test, lists of signaling proteins. This sort of memory, the one we associate with “book learning” or factual information, is called “explicit memory,” and for that you need a part of the brain known as the hippocampus.

The name means “sea horse”—that’s more or less what this structure looks like, curving along the inner wall of the temporal lobe, that part of the brain located just above your ear. Central to the neural circuitry responsible for explicit memory, the mammalian hippocampus, as Kandel had observed in his pre-Aplysia days, was an impenetrable thicket of crisscrossing fibers that defied researchers eager to infiltrate its archives. Then, in 1973, Timothy Bliss and Terje Lømo discovered that applying a brief train of high-frequency electrical stimuli to neural pathways in the hippocampus could evoke a striking activation of postsynaptic neurons, a phenomenon they called “long-term potentiation,” or LTP. Readily studied in the liv-

ing animal as well as in laboratory preparations, LTP made the hippocampus accessible and proved a powerful model for the study of explicit memory processes in the mammalian brain.

Like sensitization in Aplysia, Kandel and others found that LTP has two phases, an early phase and a late phase. Being excitatory neurons, the terminals of cells that make up LTP-sensitive pathways broadcast glutamate, which binds to AMPA and NMDA glutamate receptors on dendritic spines. Everyday low-frequency conversations engage only AMPA receptors, with no lingering aftereffects. But the high-frequency stimulation used in LTP triggers powerful depolarizations along with the release of glutamate. The NMDA receptor sneezes, the magnesium stuck in its channel flies out, and calcium flows into the dendrite. Once inside, it activates calcium-sensitive kinases. The kinases, in turn, phosphorylate AMPA receptors, increasing their sensitivity. In addition, the fuss draws more AMPA receptors to the synapse and encourages the expansion of the postsynaptic density. The end result is a stronger synapse, an effect that lasts two to three hours.

Once again, however, memories based on such cosmetic changes to synaptic proteins fade like a fresh coat of paint. Remembering facts and figures takes practice; in the laboratory neurobiologists replicate the beneficial effects of studying by applying several successive trains of high-frequency stimuli. Now calcium has a more interesting tale to tell, and it searches out a new confidant: adenylyl cyclase. News of the tryst reaches MAP kinase by way of that little tattletale, cyclic AMP, the kinase hurries into the nucleus to tell CREB, and CREB spreads the word to genes. Soon a construction crew of new proteins is on its way to the dendrites, ready to build a monument to high-frequency stimulation that will last at least 24 hours.

First, however, the crew has to find the construction site. “When you turn on genes, the products are sent to all of the synapses. But each neuron may make as many as 1,000 connections, involving more than 100 different cells. So the question is, are you enacting a

cellwide change or a synapse-specific change?” Kandel observes. And he found that the answer lies in some unusual furnishings of dendrites: mRNA transcripts, shipped and stored in an inactive form prior to all the excitement, and the machinery to carry out local protein synthesis. All the synapses have these materials. But only those “branded” during the short-term memory phase will now be allowed to use them. “You have a local marking signal,” says Kandel, “and the function of this is that it allows you to use the proteins made when genes are activated at that one synapse. mRNAs, shipped in dormant mode and activated locally, give rise to the growth of synapses.”

In effect, Kandel concludes, “neurons have two genomes. They have the genome that’s in the nucleus and then the machinery for expressing genes locally, a duplication essential to their ability to learn and adapt.”

People say that horses are “not smart” or that they are “flight animals.” But I think they are actually a lot like teenage girls. They like to run in herds. They pick on outsiders. They question authority figures. They think everyone and everything is out to get them. And when they’re in trouble, they can be counted on to panic.

Then again, inexperienced riders can act a lot like parents. They lecture instead of listening. They pay more attention to experts than their own intuition. They’re better at making rules than enforcing them. And they’re really, really bad at dealing with panic.

“Because I said so, that’s why!” My horse and I were locked in the same old argument about her head tossing; exasperated, confused, and shamed by advice from the more experienced to “stop letting her take advantage of me,” I had gone parental, resorting to an attitude already proven to be unsuccessful for dealing with adolescent infractions. She was returning the favor by acting juvenile: “I don’t get it! You don’t understand what it’s like to be a horse! You can’t make me!” Conditions were perfect for a panic attack. On a

calm, windless day, in a part of the world where a predator hadn’t been sighted in 50 years, carrying out a routine maneuver, she shot sideways so violently my neck snapped and began running.

The road was only a few hundred feet away and I knew—cold, sinking, panic knew—we were going to end up right in the middle of it. With my only other option a collision with a rapidly moving vehicle, I braced my hand on her neck and tugged repeatedly on one rein until I finally hauled her to a spinning stop. She bucked and I bailed. I walked away from what might have been a train wreck with nothing more than muddy clothes and a sore neck. But two days later I got back on my horse and I was afraid. A week later I was afraid. A month later I was afraid. And the fear wouldn’t go away.

A brain that can remember the birth of a child, how to play the piano, multiplication tables, the names of dozens of business associates, and the rules for filing an expense account can also learn to be afraid—and remember this lesson even longer than a sea slug remembers a series of electric shocks. Like any other high-intensity stimulus, terrifying events can remodel the brain, re-creating the traumatic event in the structure of neurons. The heavy lifting in this emotional memory is not the hippocampus, however, but an almond-shaped assemblage of cells about as big as the tip of your thumb, perched on the head of the hippocampus like a hood ornament. Known as the “amygdala” (meaning “almond,” after its shape), it is “the anatomical equivalent of city hall,” a crossroad where inputs from brain regions that traffic in sensory data, the perception of bodily sensations (like the bottom-dropping-out-of-your-stomach feeling you might get when racing toward a busy road on an out-of-control, thousand-pound animal), associations, rational thought, and other older memories (courtesy of the hippocampus) intersect. In other words, the amygdala is perfectly located and hardwired to connect the details of an event and the feelings they inspire, and it’s no surprise this structure has been linked to emotional behavior and emotional memory for more than a century.

In the laboratory, neuroscientists induce the pairing of neutral stimuli and fearful emotions using a paradigm that’s a combination of Eric Kandel’s technique for sensitizing snails to touch and Pavlov. A rat is placed in a cage with a floor that is actually an electrified wire grill. The animal’s first experience in the cage is uneventful—the only disturbance a mysterious beep coming from a speaker set into the wall of the cage. During the next visit, however, the sound is followed each time by a brief, harmless but unpleasant shock. Just a few shocks and the sound alone is enough to make the rat freeze in place, its heart pounding and its blood pressure soaring. The memories implanted by this “fear conditioning” are extremely long lived; months later a single reminder—in fact, any kind of stress—can reawaken it.

Joseph Le Doux, an expert on the neurobiology of emotional memory, and others have demonstrated that fear conditioning induces long-term potentiation in the amygdala much as high-frequency electrical stimulation induces LTP in the hippocampus. The development of ultrasensitive neural responses correlated with the emergence of the fearful response and, much like the animal’s anxiety at the sound of the tone, the sensitivity of amygdala neurons persisted long after the training period. And only rats that learned to be fearful developed LTP-like responses; no changes in neural sensitivity occurred in the brains of rats exposed to the tone but never shocked.

These observations suggest that fear persists after a traumatic experience because the chemical fireworks ignited in the neuronal pathways that converge on the amygdala set in motion the same processes—the phosphorylation of receptors, the inward flow of calcium, the generation of new synapses—that underlie learning and memory in the simple circuitry of Aplysia. Such restructuring in the wake of events important enough to elicit animated conversations between neurons evolved to promote survival, to help us recognize potentially lethal situations and take action before it’s too late. But

when fear endures long after the original danger is gone, it can become debilitating instead of advantageous.

“If you want a building to learn,” writes Stewart Brand, “you have to pay its tuition.” The price we pay for having an adaptive nervous system in which memory is possible is that memory will be too effective, that outdated, inaccurate, or misleading information will be retained along with the good and the useful. Welded to the facade of proteins or built into the membranes of dendrites, such misinformation cannot be erased quickly or easily.

Denise is another example of the grief that can ensue when neurons retain the wrong things. “I always said that if they ever came to take away my children, that would be the end of the world. I would stop,” she says. Stop abusing cocaine, she means. Too bad the experience of getting high had already written itself into her brain.

“For a while, I still used to go to work every day, cook dinner, take the kids to the mall on Friday. Then I stopped going to work. I stopped paying the bills. The car was gone, next the house was gone. And then the kids.”

“I had two at home with me, and they took them while those kids were crying and holding on to the banisters. Then they went up to the school. My daughter called me and said, ‘Mom, I’m scared. Someone’s here to take me away.’ It hurt me more than anything ever hurt me in my life. And still I couldn’t stop.”

All substance abusers take drugs. Those who become addicted, however, are changed in a fundamental physical way by the experience. As a result, they can’t stop taking drugs, even in the face of profoundly negative consequences.

Their predicament stems from the fact that cells communicate in chemicals, meaning that cellular communications, including discussions between neurons, are accessible to outside influence. A drug that looks like a neurotransmitter, socializes with its receptors, or interferes with its clearance once transmission is completed can trigger the same sequence of events as a legitimate synaptic discourse—including alterations in gene expression. As a result, neurons can

“learn” from their experiences with drugs just as they learn from other life experiences and retain this information for long periods of time.

Learning from drugs can be helpful. Antidepressant medications like Prozac and Zoloft, or the antipsychotic medications used to treat schizophrenia, for example, use their influence to calm troubled neurons. The adaptations they induce relieve symptoms, restoring patients’ ability to lead productive lives.

Addictive drugs tell beautiful lies. They also remodel the brain, but the adaptations they induce are anything but beneficial. Over time, the small changes in gene expression that follow in the wake of every exposure to the drug accumulate and lead to profound and persistent changes in the structure and function of neurons. When these changes reach a critical threshold, drug abuse slides over into addiction and drugs are no longer an option but a compulsion.

Drug-induced adaptations are concentrated in the neural circuitry governing emotion and motivation—particularly so-called reward pathways. Here, their favorite targets are the neurons that use the catecholamine dopamine as a neurotransmitter. Under normal circumstances the wavelet of dopamine these neurons emit when they want to announce a positive experience—a delicious new food, for example, or a behavior that led to praise—records the event along with the label “good,” increasing the likelihood the behavior will be repeated. Addictive drugs add bigger labels and flood the synapse with “levels of dopamine never found in nature,” according to neurobiologist Eric Nestler. The surge of dopamine masquerades as an urgent message: “This is the most important thing that’s ever happened to this brain—and don’t forget it!” Too much exposure to this noise and drugs come to seem more essential than anything else—even your children.

A nervous system built to adapt gives us the flexibility to cope with a wide range of contingencies. But when traumatic experiences or addictive drugs muscle into the signaling pathways at the heart of this

flexibility, the brain can also be waylaid by its ability to change. Or in Steven Hyman’s words, “Not all adaptations are good for the organism.”

Memories engraved in the fabric of the brain cannot be willed away, ignored, or rationalized. “If you can’t get over your fear factor, maybe you should quit riding,” one self-styled expert advised in response to my unrelenting anxiety. It’s an attitude someone like Denise would recognize all too well: “If you can’t give up drugs, you should quit raising children.” Unfortunately the brain just doesn’t work that way. The moral imperative of neurons is to ensure the survival of the body, preserving the memory of experiences that threaten or enhance life regardless of whether they conflict with social standards, circumvent the rule of law, or prove inconvenient at a later time.

The only antidote to destructive memories is constructive memories. I couldn’t erase my fear by sheer willpower. But I could learn a different style of riding, better ways to cope with an emergency, and how to spot the little cues that meant my horse was reaching the limits of her patience. And gradually, memories of good rides—a jaunt through the woods on a blue-sky autumn morning, jogging a perfect serpentine—are overwriting the memory of the accident.

I don’t know what’s happened to Denise since she left the halfway house where I met her. I hope she’s at home tonight, cooking dinner for her kids, rather than in the hospital, on the street, or in prison, knowing that like the fearful, the addicted can learn to out-wit the memory of drugs. Relapse remains an ever-present risk. But in the long run, teaching people to change is more likely to succeed than putting them in jail, for no punishment, however harsh, can reverse or negate the damage addicts have done to their own brains.

The good news for us, with our adaptable brains, is that flexibility is the agent of hope. As long as neurons converse and synapses multiply, the capacity for change will not diminish. What we learn,

we may not be able to unlearn, but we can relearn, replacing memories that have outlived their usefulness with new and better ones.

THE ART OF WAR

The phone rings as you pause to hand your secretary a draft of the new proposal en route to your 11 o’clock meeting. “Wait, it’s for you,” she says, sneezes, then hands you the phone. You’re thirsty after the conversation, so you stop for a quick drink at the water fountain—the same fountain where the receptionist rinsed out six coffee mugs a few minutes earlier. You drop your notepad on the conference table and decide to sample the doughnuts laid out on a table at the back of the room. Good, there’s still a chocolate one left. It’s the one your boss picked up, then, remembering her diet, put back before you arrived. You sit down, pull yourself up to a table touched by three other people earlier this morning, and rest your hands on the arms of a chair used by two of them as well as someone at last evening’s after-hours brainstorming session. As you’re shaking hands with the prospective vendor (and the four staff members he’s brought along), you realize that you’ve forgotten to bring a pen. Your neighbor has an extra; fortunately, he’s looking the other way when you nibble absentmindedly at the tip. When the presentation is finally over, you shake hands with everyone again, help your pen-sharing colleague collect the used napkins and empty cups, and sprint for the company cafeteria. You think of stopping to wash your hands, but you have only 20 minutes to grab lunch, check on your secretary’s progress, and hustle over to the next building for your one o’clock meeting.

Even if you’re single, celibate, and profoundly antisocial, you can still have an astonishing amount of intimate contact with your fellow human beings. If this had been an actual workday, you would have inadvertently rubbed shoulders with more than a dozen people. You would not have shared a single detail of your private life—home

phone number, shirt size, political affiliation, or the incident that precipitated your divorce—with any of them, but you would have shared something more personal and potentially more damning: their microorganisms. Given the number of bacteria and viruses you could have inhaled, picked up, or swallowed along with your chicken salad sandwich, you’re lucky that under the skin you’re defended by one of the most effective fighting forces on the planet—the human immune system.