The Language of Life: How Cells Communicate in Health and Disease (2005)

Chapter: 3 Plaiting the Net

3

PLAITING THE NET

Have you ever thought, while you’re struggling to balance a bag of groceries, the dry cleaning, the videos your kids forgot to return yesterday, a two-liter bottle of diet soda, and the car door that it would be really, really helpful to have an extra arm or two? If only you had realized how easy it would have been to create a limb when you were an inch-long embryo—all you would have needed were the right words.

Just in case you ever manage to turn back time, those words are “fibroblast growth factors.”

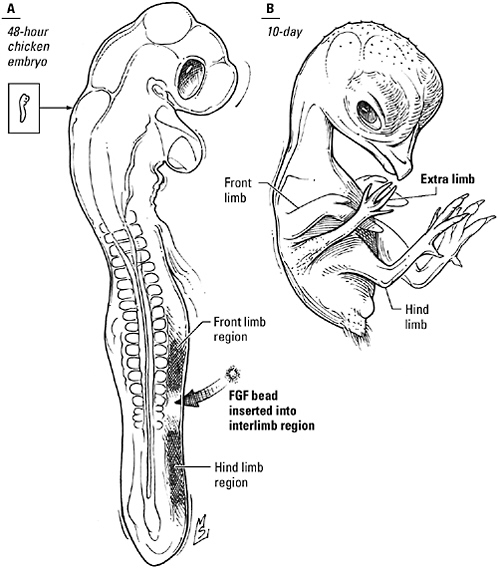

Vertebrate limbs begin as little hillocks of undifferentiated tissue known as “limb buds” that erupt at precise spots along the lateral edge of the embryo. More than 50 years ago, embryologists analyzing the development of legs and wings in the chick embryo discovered that the outgrowth of these limb buds was masterminded by a lip of tissue curving around the leading edge of the bud, the apical ectodermal ridge: If the ridge was cut away, the limb stopped growing; if it was rotated 90 degrees to the left or right, the limb grew outward from the body at right angles to its normal orientation. But it wasn’t until the 1990s that scientists learned that fibroblast growth factor, or “FGF,” was what the ridge said to the bud. A plastic bead

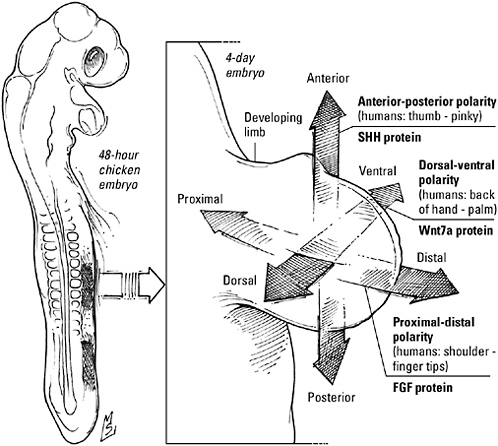

impregnated with FGF and apposed to the stump after amputation of the apical ectodermal ridge could substitute for the missing tissue, spearheading the development of a complete wing or leg indistinguishable from a normal limb. What’s more, researchers learned, a little FGF on a bead could not only rescue an established limb bud, it could also make an extra limb sprout in the space between wing and leg. “You get a complete limb,” says developmental biologist Cliff Tabin, “a humerus, a radius and ulna, a wrist, and digits.”

How to make an extra limb. A bead impregnated with fibroblast growth factor, implanted in the side of a 48-hour-old chick embryo, triggers the development of an extra wing or leg.

Prefer something a little more realistic? No problem—a pellet of FGF-secreting cells can be substituted for the bead. And don’t be concerned because you aren’t a chicken. So-called knockout mice, created by scientists wielding genetically engineered weapons that allow them to take potshots at specific genes, have shown that FGF is as important to limb development in mammals as it is in birds. Provided you’d taken care to apply FGF before your two normal arms began to develop, you would have been on your way to increased dexterity without a second thought.

Perhaps, if you have young children, you could use eyes in the back of your head, as well as an extra arm. In that case, you should have added “bone morphogenetic protein number four,” or “BMP4,” to your vocabulary. In collaboration with FGF, BMP4, secreted by the optic vesicle (a pedestal of tissue protruding from the embryonic brain), talks nearby cells into fashioning the eye’s lens; signals issued by the lens, in turn, instruct the optic vesicle to make a retina. If you had grafted a couple of these BMP4-secreting optic vesicles under your scalp, today you’d be able to keep an eye on what’s happening in the rear seat without ever taking your eyes off the road. Maybe you’re a pianist or a writer, and a few additional fingers would be more useful than another arm or a second pair of eyes. If so, the phrase you needed to know was “Sonic hedgehog.” A pellet of cells producing this signaling molecule, implanted in the head of the limb bud, would have given you a duplicate set of fingers. Or maybe you prefer brains to brawn. Provided you don’t mind people staring at you as if you had two heads—because you would have two heads—your word would have been “Cerberus.” With the correct words (“Noggin” and “Chordin”) and good timing, a truly narcissistic individual could even generate a Siamese twin—given, that is, the individual in question was a narcissistic amphibian.

Arm or eye, animal or human, house or cathedral, a building project of any complexity is necessarily a collaborative effort. As art histo-

rian J. J. Coulton puts it, “Whereas a statue can in most cases be completed by one man with his own hands, this is normally impossible in architecture.” As a result, Coulton observes, the evolution of architecture in ancient civilizations could not have occurred without the evolution of techniques for describing buildings and their construction, “to communicate the architect’s intention to the builders.” For example, builders in Egypt and Mesopotamia carved outlines of proposed structures on clay tablets or sketched them on sheets of papyrus—the earliest known examples of the architectural ground plan. Egyptian architects also pioneered the use of front- and side-view elevation drawings. What’s more, these drawings were rendered on papyrus divided into squares, evidence that their creators were already familiar with the square grid as a technique to specify proportions.

Metazoans embarked on a building program as ambitious as that undertaken by any ancient civilization and as equally dependent on effective communication. Much as the progression from tents to pyramids went hand in hand with the invention of the floor plan and the square grid, the progression from single-celled organism to a multicellular body correlated with the evolution of mechanisms for stipulating the spatial relationships between specialized tissues dedicated to the administration of distinct physiological functions. In place of brush or stylus, multicellular organisms had only chemicals; using no more than the pattern language of design elements so valuable in other contexts, they were expected to discriminate head from tail, mark the placement of limbs, ensure that the eyes were in the head and the feet on the ground.

But these enterprising creatures faced a technical challenge more formidable than any confronting their human counterparts. An architect undertaking the construction of a temple or palace began with stacks of bricks, yards of timber, and legions of slaves. A metazoan embryo began with a single fertilized egg.

“Ex ovo omnia”—all come from eggs—physiologist William Harvey

declared in 1651. But how did a large, complex creature emerge from such humble origins? The naturalists and philosophers of ancient Greece were among the first to search for an answer to this riddle. Some studied birds’ eggs and the fetuses of domestic animals and declared that a fully formed creature was present from the very beginning, only much, much smaller. For these “preformationists,” development was about growing larger, a grace period in which the youngster took shelter in the egg or the womb until it was big enough to survive in the outside world. Others, led by Aristotle, examined the same materials and reached a totally different conclusion. They claimed that the embryo began not as a miniature adult but as an undifferentiated mass. Structure and organization emerged gradually, “as we read in the poems of Orpheus, where he says that the process by which an animal is formed resembles the plaiting of a net.” Epigenesis, as this viewpoint came to be called, held that development was a time of differentiation and maturation in which the organism grew in complexity as well as size.

“If organic form is not original, but is produced, what accounts for regularity and directedness of process? And how do all individuals of the species end up with the same body plan, the same organization of the internal organs, the same proportions of each type of cell?” Epigenesis, with its insistence that living things were constructed rather than created, raised uncomfortable questions about the nature of development. What mysterious force or invisible hand guided the embryo’s journey from nonentity to individual? The shadow of heresy was not enough to deter Harvey, but most of his contemporaries were slavish devotees of preformation. Pious sorts clung to preformation because it could be reconciled with their belief in a Creator-God. And the enlightened embraced it because it appealed to their belief in an orderly universe; they saw, in the systematic appearance of generation upon generation of prefigured organisms, a scheme as law abiding as the movement of the stars or the actions of gravity.

You might think that the introduction of the microscope would

have settled the argument. It did not. If “seeing is believing,” most still wanted to believe in preformation, and so they convinced themselves that they saw little men and tiny animals when they peered into their microscopes.

Others finally dared to believe their eyes. Let those blinded by long-standing prejudices defend the faith. “What [one] does not see is not here,” insisted Caspar Friedrich Wolff, one the first of these revisionists, in 1759. Gradually and grudgingly, even the most resolute had to agree. But while the wholesale conversion to epigenesis put an end to fictitious accounts of miniature organisms, it brought biologists face to face once again with the old question of how the egg gave rise to a fully formed organism.

When preformation was the order of the day, embryologists had the easiest job in biology—if the embryo did nothing but grow, the study of development required no more than watching and waiting. But the mechanisms underlying epigenesis could not be deduced by observation alone. To solve this problem, scientists had to use their hands as well as their eyes. Wielding needles, scalpels, and dyes, they turned developmental biology, long a spectator sport, into an experimental science.

In 1901, Hans Spemann, a lecturer in zoology at the University of Würzburg and one of the new evangelists of the experiment, published a paper explaining how the tadpole got its eyes. In the frog Rana fusca, as in other vertebrates, development of the eye begins with the optic vesicles, situated on either side of the primordial brain. As the vesicles expand, they contact the overlying tissue, or ectoderm, retract, and differentiate to form the retina, while the ectoderm itself pulls away and divides to fill the cup of the developing retina; this filling becomes the lens. Spemann suspected that the vesicle somehow influenced lens development; to test his hypothesis, he used a scalpel made from a glass needle and a loop of baby’s hair to pinion the tiny embryo and excise, reposition, or exchange slivers of tissue.

Spemann reported that when he removed the entire optic vesicle early in development, neither eye nor lens developed on that side of the embryo. But if he left even a remnant of vesicle tissue in place, next to the ectoderm, an extraordinary thing happened—despite the absence of a complimentary retina, the ectoderm still developed into a lens. Furthermore, lens making was a secret peculiar to the optic vesicle. Other tissues, transplanted to the head, could not make a lens. But if the vesicle was cut free of the brain and moved so that it contacted the ectoderm of the trunk instead, why, a lens formed there, in the belly of the tadpole! Spemann concluded that lens development was directed by a very private and specific conversation, in which the optic vesicle induced the production of a lens through some sort of exchange with the receptive ectoderm.

The most obvious way for one tissue to communicate with another was by touch. At first that was the way scientists like Spemann thought embryonic induction occurred. But in 1952 another researcher—a mathematician, not an embryologist—suggested that transactions between tissues during development might also be couched in the language of chemistry. In a paper entitled “The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis,” Alan Turing (better known as one of the pioneers of computer science) proposed a model “by which the genes of a zygote may determine the anatomical structure of the resulting organism,” based on the hypothetical interactions between two substances he called “morphogens” (“form-giving molecules”). Turing’s “reaction-diffusion” model posited that these substances, when mixed together, diffuse freely and interact in two different ways. Morphogen A, which diffused more slowly than Morphogen B, was a catalyst; it enhanced not only its own production but that of Morphogen B as well. Morphogen B, on the other hand, diffused rapidly and inhibited the production of both substances. Turing’s mathematical analysis revealed that under certain conditions the interaction of Morphogen A with Morphogen B could generate recurrent spatial patterns, peaks and troughs of morphogen concentration similar to the regularly spaced patterns of leaves, pet-

als, tentacles, and stripes found in plants and animals—suggesting that the distribution of chemicals could indeed draw a “floor plan” that cells might translate into biological structure.

Floor plans and elevations gave architects of antiquity what Coulton calls “a technique of design,” a solution to the problem of how to communicate the placement of doors, the spacing of columns, or the dimensions of rooms to builders. Similarly, patterns based on the spatial localization of chemical signals represented a “technique of design” that metazoan organisms could use to solve such problems as the placement of organs, the shape of the body, and the differentiation of specialized cells. In these patterns the developing embryo could discern the fates of cells and extract the information needed to craft an entire body, step by step, from a single cell.

MEET THE CONTRACTORS

A completed arm is an alliance of nerve and muscle, skin and bone, tendons and joints. But what makes a nerve cell nervous or a muscle cell muscular? In the cellular world, personality is based on proteins. Each type of cell is characterized by the unique constellation of proteins it synthesizes: neurons make ion channels and pumps that control the concentrations of ions and the propagation of electrical impulses, muscle cells string cables of protein fibers and mount protein motors to crank them taut, red blood cells pack themselves with hemoglobin for carrying oxygen, cells lining the gut produce enzymes to break down food. Each elaborates its own protein repertoire, yet all came from an egg containing the only copy of the organism’s genes.

When embryology was a young science and developmental genetics had yet to become a recognized discipline, one popular explanation for this paradox held that the genetic material bequeathed to the egg was divided among the daughter cells in the early rounds of cell division. A cell’s fate was determined by its particular allotment:

cells that received muscle determinants gave rise to muscle cells, those that received determinants peculiar to the skin gave rise to skin cells, and so on. In modern developmental biology, the Great Partition has been superseded by the Great Decision. During development, we now know, the genome is copied and forwarded in its entirety, at every cell division, to all progeny of the original egg, not split up and parceled out. Each cell, however, actually uses only a fraction of the thousands of genes held in common. As it progresses from egg to embryo to newborn, the cell can alter its gene selections in response to external cues, including signals issued by its neighbors. At maturity a cell’s final identity is a summary of the decisions it has made regarding gene expression, culminating in the selection of a battery of genes encoding the proteins needed to perform a single specialized task.

“DNA makes RNA makes protein.” That’s the mantra you may have memorized in high school biology, but in the living cell there are a lot of “ifs,” “ands,” and “buts” in between. These contingencies enable cells to use the same genome in a multitude of ways, decisions that chart the course of embryonic development.

Manipulating the expression of genes in eukaryotic cells is so easy because transcribing eukaryotic genes is so hard. Before a gene can be transcribed at all, it must have permission. Even then, RNA polymerase, the enzyme that actually does the work, is baffled by the way DNA is twisted, scrunched, and tied up in protein in order to pack it into the chromosomes; is all thumbs when it comes to unraveling the double helix; and is clueless about the right way to straddle a strand once it’s unwound. If cells had to wait for the polymerase to figure out transcription on its own, the job might never get done.

To make proteins, DNA needs proteins, a corps of mechanics and decision makers that biologists call “transcription factors.” These proteins come in two flavors. So-called general transcription factors assemble at the promoter sequence where transcription begins; they recruit the polymerase and orient it correctly. Other transcription

factors are activators and repressors that permit or forbid gene expression. They bind to a distinct regulatory sequence that is not part of the gene itself and may, in fact, be located a considerable distance upstream or downstream. Gene activators give a thumbs up to RNA polymerase, recruit and organize the enzyme’s crew of general transcription factors, and exhort the whole conglomerate to work harder and faster. Repressors stifle gene expression by blocking the binding of activators, interfering with their recruiting efforts, or smothering the DNA in more protein.

Both activators and repressors recognize and bind to DNA regulatory sequences much as receptors recognize and bind signaling molecules or interaction domains detect consensus sequences. If the idea seems surprising that’s probably because you’re used to thinking of the DNA double helix as a ladder. In reality it’s a spiral staircase of rough-hewn stones—its constituent bases, each outlined in a characteristic pattern of chemical features more or less eager to form transient bonds with passersby. Collectively, these features generate a surface as unique as that of any protein. Just as scaffolding proteins contain interaction domains that correspond to consensus sequences, transcription factors have evolved structural motifs that “read” DNA sequences by interacting with the surface features of the bases contained in that sequence. Some sport a coil, or a loop closed with an atom of zinc that fits into a groove of the helix. Some contain a strip of adhesive amino acids that latch on to their cognate sequences like Velcro. Others grip the DNA like a clothespin or join hands with a second gene regulatory protein and encircle it.

In a classic series of experiments carried out in the 1950s, François Jacob and Jacques Monod revealed how transcription factors enable even an organism as unpretentious as E. coli to use the information stored in its genome selectively. The well-prepared bacterium has genes for enzymes that allow it to metabolize two sugars: glucose, its preferred food, and lactose. In addition, it has two regulatory proteins that allow it to change its complement of metabolic

enzymes to suit today’s menu. When lactose is unavailable—or glucose is plentiful—Jacob and Monod found that an inhibitory transcription factor, the lac repressor, shuts down transcription of the gene that encodes the lactose-processing enzyme, conserving time, effort, and raw materials that would otherwise be invested in producing an unnecessary protein. But when lactose is the only lunch option, E. coli substitutes an activator called CAP for the repressor, turning on the enzyme gene so that it can digest this sugar. No matter what the environment serves up, by micromanaging its genes, E. coli can endeavor to stay well fed while husbanding energy and resources.

Many eukaryotic genes seem to have felt transcription was too important to be entrusted to a single regulatory protein. Their expression requires the combined input of an entire consortium of transcription factors. The imposition of additional constraints not only afforded eukaryotic cells an exquisite degree of control over gene activity but also offered unlimited opportunities to customize gene expression at different times and in different places, merely by increasing or decreasing levels of the gene regulatory proteins that collectively determine whether the gene is turned on or switched off. In addition, by integrating transcription factors into signaling pathways, gene expression could be placed under the aegis of external signals, granting a cell’s neighbors the power to induce long-standing changes in its behavior, its activity, or even its identity.

Although it is often compared to a blueprint, the genome is more like a home design magazine, full of clever ideas, new products, amazing gadgets, and grand decorating schemes—only some of which are useful. Contractors and homeowners, paging through these options, must select the features best suited to the task at hand. All-white cabinets? Impractical with toddlers. Shiny chrome fixtures? Too old-fashioned—brushed nickel is what everyone’s choosing these days. A prefab shower won’t fit the space; the hand-painted ceramic tile won’t fit the budget.

Embryonic cells, committed to a building enterprise that makes a kitchen renovation look like a child’s craft project, also have choices to make—choices about genes. The dynamic control of gene expression via transcription factors and signaling pathways facilitates these decisions. During development, each cell’s contractors and homeowners—transcription factors and the extracellular signals that boss them—page through thousands of options to select the right genes, first to frame and then to finish the organism. Just as the configuration of the plumbing determines the placement of the sink, the size and shape of the sink affect cabinet selection, the finish on the cabinets determines the best tile color, and the amount still left in the bank dictates whether it will be paint or paper, the decisions cells make at one phase of development determine their options in the next phase. Today’s effect becomes tomorrow’s cause, and successive rounds of gene expression gradually partition the embryo into smaller and smaller populations of like-minded and increasingly specialized cells, each characterized by a distinctive pattern of gene activity and, as a consequence, a distinct repertoire of proteins. Manipulating genes in sequence, neighbor guides neighbor as the embryo maps out the rudiments of a body plan, then builds on that foundation to assemble a mature organism.

THIS END UP

Writers are derailed by writer’s block, musicians and actors by stage fright, but if any group of artists has a right to be paralyzed by fear of failure, it’s architects. As Coulton observes:

A man modeling a clay figure can … to a certain extent modify the part formed first in the light of what he does next, and can even reject the whole form and start over again without much loss; a painter is in much the same position. The sculptor working in marble is rather more constrained, for a serious mistake will be both irremediable and costly, but he can work gradually into the stone over the whole of his figure, so that the relation of the parts to each

other can be clearly visualized at a stage where minor changes to any of them are still possible. The architect on the other hand must always start his buildings at the bottom and cannot modify at all what he has built first in light of what follows. Mistakes made at the start can therefore not be corrected, and they will also be ruinously expensive.

A developing embryo also must start at the bottom, cannot look back, and pays a heavy price—death or disfigurement—for mistakes. To “ensure that the lower parts of the building will suit the parts to be put upon them,” the embryo’s floor plan must answer fundamental questions about orientation and layout, or its project will collapse before it ever sees the light of day.

Specifically, developmental biologist Marc Kirschner says, the nascent embryo must accomplish three critical tasks. First and foremost, it must acquire a sense of direction. “The first thing you need is some global organization, some global polarity—head-to-toe polarity, back-to-front polarity. If you had a lot of autonomy, you could easily imagine an organism sprouting multiple heads. So early on in the process of development, you have to have some sort of way of generating a polarity in the organism that will establish the early anatomy of the organism, will absolutely dictate that anatomy and not allow for deviations from that,” he says. Biologist John Tyler Bonner goes even further. “Perhaps the most fundamental property of any development—including the development of unicellular organisms—is polarity,” he writes, a feature so basic, so ancient, it can be considered a “kind of living developmental fossil.”

“The next thing would be an inside and an outside,” Kirschner continues. Sealing off the interior is an essential prelude to the acquisition of a “capacity for reliable signaling within the organism,” as Kirschner calls it, the faculty that enables the embryo to realize complete mastery over the behavior of its constituent cells. To achieve this goal, the clump of cells formed during the first cell divisions must be drawn apart, rearranged, or carved out to form a hollow sphere, in which some cells face outward and bind together to form

a secure barrier—an epithelium—while the rest retreat inward. The fastidiously composed fluids contained within the epithelium will constitute their reality, the signals dispersed within it, the voices that will guide them for the rest of their lives.

Finally, Kirschner argues, the embryo must mark out a system of compartments that will be the basis for all subsequent differentiation; having laid the foundation, it must frame out the rooms, as it were, by manipulating gene expression to subdivide the front-to-back and top-to-bottom axes specified in the first step. Embryos, he says, need “mechanisms to set up an ‘invisible anatomy’ of signaling pathways, often in a sort of segmental pattern, anterior to posterior, and another invisible anatomy to set up an invisible pattern from dorsal to ventral.” For example, patterning mechanisms might mark out 20 segments from head to tail and 10 divisions from back to front, a total of 200 individual domains. Within each of these compartments, cells share a common bond—a pattern of gene expression found only in that compartment and no others. “This allows the first major kind of modularity,” Kirschner concludes. “All those cells, they may develop into things very different within those domains, but they’re different from every other domain in that they have that special address”—and that common pattern of gene expression.

Polarity, insularity, modularity—these three properties abide in metazoan embryos. But the greatest of them is polarity.

Instant polarity—just add water. To set a course, an embryo must have a compass, and morphogens—the diffusible, form-giving substances proposed by Alan Turing—suggest one way to point the youngster in the right direction. The embryo can simply take advantage of the fact that as a diffusible chemical flows from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration, it automatically creates “a directional arrow that points down the slope of the [concentration] gradient.” To learn how far back or how close to the top

they are, cells “read” the concentration gradient; based on this information, they activate a corresponding battery of genes, translating the polarized spatial pattern formed by the chemical into a molecular pattern capable of generating a spatially organized body.

To illustrate this principle, developmental biologist Lewis Wolpert suggested how a group of patriotic cells might use “positional information” (as he called it), supplied by a morphogen gradient, to turn themselves into a replica of the French flag. Wolpert asks readers to imagine a row of cells, lined up end to end like the threads of a strip of cloth. A chemical signal, released from a reservoir on the left side of the row, diffuses from left to right, creating a concentration gradient. Each cell decides whether to activate genes for the color red, white, or blue on the basis of the concentration at its position in the gradient: cells closest to the reservoir, exposed to the highest amount of the morphogen, become blue; those farthest to the right, where morphogen levels are lowest, elect to be red; those in between, where morphogen levels are too low to turn on blue genes but too high to turn on red, become white.

On paper the morphogen gradient is a sensible candidate for an embryonic patterning mechanism; indeed, it has been one of the most pervasive models in developmental biology. In practice, identifying real morphogens has posed one of its most significant challenges. Scarce, elusive, and short lived, they slip right through the clutches of standard purification techniques. Genetics, in such cases, can often accomplish what biochemistry cannot—a rare protein that lurks in the shadows may be flushed out by a fortuitous mutation, trapped or tracked following the identification of its gene. But until the mid-1980s, every geneticist’s favorite organism, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, was hardly the ideal subject for studying the genetics of early development. Flies with odd eye colors or extra wings can survive and breed in the sheltered environment of the laboratory, but a fly embryo with a mutation in a gene critical to development—a gene, for example, that differentiates its head from

its tail—is likely to die long before it ever sees the light of day. Figuring out what went wrong with a dead embryo in a tiny opaque egg frustrated even the most resolute; as developmental biologist Scott Gilbert notes, “‘Death’ is a difficult phenotype to analyze.”

Then, in the 1980s, German embryologists Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard and Eric Wieschaus learned that a simple trick—soaking the fly’s eggs in oil—rendered their impenetrable shells transparent. Even the youngest embryos could be observed in these eggs-turned-fishbowls; once their DNA was scanned for aberrations, Nüsslein-Volhard and Wieschaus could then correlate phenotype and genotype to determine the roles played by specific proteins at every stage of development.

One of the thousands of embryos Nüsslein-Volhard, Weischaus, and their colleagues described was a monstrosity with a second tail where its head and thorax ought to have been, the product of an accident involving a gene they christened “bicoid.” Cytoplasm from the anterior end of a normal embryo could counter the mutation, further evidence that the protein product of bicoid mediated the all-important task of orienting the embryo. But the bicoid mutation wasn’t a flaw in the embryonic genome. This mistake was committed in the genome of the mother fly.

Parents everywhere want to do what they can to help their children. Detached as she may seem, the female fruit fly is no exception. She may not build a nest or fetch food, but she does make sure her off-spring will know their heads from their tails, planting clues in the egg the embryo can use to jump-start the crucial axis-building enterprise. Her gifts are mRNA transcripts and they are recipes for morphogens.

The bicoid transcript, tethered to a complex of anchoring proteins at one end of the ovoid egg encodes one of these maternal morphogens. In the dialect of Drosophila, “bicoid” means “head.” Translated into protein, bicoid yields a transcription factor that diffuses away from this end of the egg to form a concentration gradient

pointing in the head-to-tail direction.* To be sure the embryo understands, the mother fly reinforces the message: in addition to bicoid, she has secured a complementary transcript at the other end of the egg. The protein encoded by this mRNA, Nanos, diffuses in the opposite direction, generating a gradient that points from tail to head.

In contrast to the bicoid and nanos transcripts concentrated at the front and rear of the egg, respectively, two other maternal mRNAs, hunchback and caudal, are plastered more or less evenly throughout. As Bicoid and Nanos diffuse, they fiddle with the expression of these ubiquitous transcripts. Bicoid activates hunchback. As a result, the Hunchback protein, another transcription factor, is actually produced only in the anterior portion of the embryo; in more posterior regions, there’s no Bicoid to turn hunchback on. Conversely, Bicoid binds and strangles caudal mRNA, limiting translation of the Caudal protein to the tail end of the embryo. Nanos has it in for hunchback. It modifies the hunchback transcript and renders it indecipherable. Concentrations of Hunchback protein, therefore, plummet as soon as the transcript encounters the leading edge of the Nanos gradient. When all is said and done, the Hunchback protein defines a head-to-tail gradient that reinforces the polarity specified by Bicoid, while the Caudal protein forms a tail-to-head gradient that backs up Nanos.

The female fly decorates the egg with instructions for distinguishing its back from its belly as well. When the embryo is ready to work on this problem, about an hour and a half after fertilization, it opens and decodes Mother’s last mRNA transcript, spray painting

itself with a mist of Dorsal protein. Unlike Bicoid and Nanos, however, Dorsal cannot diffuse. Tethered in place to a chaperone protein, this transcription factor can’t even get into the nucleus, much less manipulate genes, until it’s liberated from its minder.

There—can you hear it, wafting up from the cells lining the base of the ovarian follicle? It’s Mother’s sweet angelic voice, crooning a lullaby that lulls the chaperone to sleep. Free of its grasp, Dorsal can gambol into nuclei. Well, some nuclei, anyway. Follicle cells have soft voices, and their song won’t carry all the way across the egg. A short distance away, receptors are already straining to hear it; back up to the equator, and it’s no more than a whisper; a little farther away, and it can no longer be heard at all. The fainter the signal, the less Dorsal liberated from the chaperone; the lower the concentration of free Dorsal, the less Dorsal-inspired gene expression. And the less influence Dorsal exerts, the closer that region of the embryo will be to the back of the fly.* Instead of a chemical gradient, the embryo reads a gradient of activity, created by a ventral-dorsal variation in the liberation and translocation of Dorsal, under the aegis of a ventral-to-dorsal variation in a maternal signal. Just as gradients of Bicoid and the others polarize the embryo in the head-to-tail direction, this gradient of nuclear Dorsal points the way from the bottom of the embryo to its back.

Using just a handful of transcription factors and RNA-binding proteins—a natal gift from its mother—the fruit fly embryo has sketched a floor plan for a body. It has marked the location of front door and back porch, calculated the depth of the cellar and the height of the roof. With the foundation completed and the framework begun, the embryo’s next task will be to add detail to the pattern, subdividing the anterior-posterior and dorsal-ventral axes to define “a

coordinate system that can be used to specify positions,” Kirschner’s invisible anatomy of compartments.

In the anterior-posterior direction, the interaction of the four products of the so-called maternal effect genes—Bicoid (front-to-back), Hunchback (front-to-back), Nanos (back-to-front), and Caudal (back-to-front)—defines a series of bands characterized by unique combinations of transcription factors. Within these crude compartments, those combinations trigger the expression of a second wave of embryonic genes, known collectively as the gap genes. New transcription factors encoded by the gap genes then diffuse and cross paths themselves, creating a series of even smaller compartments and recruiting the so-called pair-rule genes to staff them, each expressed in seven alternating stripes. Together, they partition the embryo into a total of 14 divisions, known as “parasegments,” a temporary organization reminiscent of—but slightly out of register with—the familiar segmental pattern of the fly larva. Now, after a blissful period in which diffusion knew no bounds, the developmental process introduces a new complication: cells. Fingers of plasma membrane separate and surround the nuclei, putting a stop to this nonsense of using transcription factors as morphogens. It’s time to break out the signaling proteins.

In the border country where one parasegment is to end and the next should begin, a pair of complementary signaling molecules initiates a quarrel that will establish the line dividing one from the other. At the posterior edge of each parasegment, a band just one cell wide marks its side of the boundary with the word “wingless.” When the cells on the other side of the boundary—the anterior end of the next parasegment—hear their neighbors posturing, they reply with an admonition of their own: “Hedgehog!”* “Maybe you didn’t hear us the first time,” the first cells retort, “Wingless!” “You’re the ones who can’t hear,” their antagonists counter. “Hedgehog! Take that!”

Tit-for-tat, the two carry on like a pair of fishwives, locked in a self-perpetuating tape loop that demarcates a clear and stable boundary separating each parasegment from the next in the sequence.

The final step in the construction of the anterior-posterior “invisible anatomy” is the activation of genes charged with locking in the longitudinal pattern and specifying the anatomical features characteristic of each subdivision in the mature fly, from the mouth parts in the front of its head to the segments of the abdomen. Known as the “homeotic selector” or “Hox” genes, they encode gene regulatory proteins and are arranged along chromosome 3 of the fly in the same linear sequence as the structures they specify. Heading the lineup is labial, which defines the architecture of the head. A little farther along the chromosome, Antennapedia governs the placement of a pair of legs and a pair of wings, while Ultrabithorax defines the segment responsible for the balancing organs known as halteres. Abdominal A and B take charge of the abdomen. Because they determine the identity of each segment, mutations to Hox genes scramble the head-to-tail organization of the body plan. Mistakes in Antennapedia, for example, produce flies with antennae where they ought to have legs, while misexpression of Antennapedia in head segments yields a fly with legs sticking out of the top of its head.

The maternal effect genes, the gap genes, and the pair-rule genes are transient phenomena, but once the Hox genes are activated they will not be turned off. Regulatory proteins included among their targets maintain the status quo in each segment, locking the subset associated with that segment in the “on” position and mothballing the rest. As a result, the patterns invoked by these genes are set in stone, irrevocably committing cells that express them to specific fates, appropriate to their location along the length of the embryo.

The interactions of signaling molecules and the genes they manipulate partition the embryo into smaller compartments along the dorsal-ventral axis as well. In the nether regions farthest from the maternal signal that releases Dorsal from bondage, the silence is

pierced by a childish voice chanting “Decapentaplegic. Decapentaplegic.” This immense musical word is an embryonic antonym for Dorsal, a diffusible protein signal spreading downward to form a countergradient in the dorsal-to-ventral direction. Together, the complementary gradients of Dorsal and Decapentaplegic reinforce the definition of the top and bottom of the embryo much as the complementary gradients of Bicoid and Nanos reinforce the definition of head and tail.

Time out for a vocabulary lesson.

Decapentaplegic is your introduction to another clan of signaling proteins—actually, an offshoot of the extended family headed by a patriarch called “transforming growth factor-β” (TGF-β). Numbering about 20 members altogether, they are known collectively as “bone morphogenetic proteins,” or BMPs, because of their felicitous effects on bone growth. All are actually twins (though not necessarily identical), a pair of polypeptide chains shaped “like an open hand with a pair of extended fingers.” The two live and work together, the “fingers” of one cradled in the “heel” of the other. And all 20 take similar compound verbs, a complex of two receptor kinases targeting the amino acids serine or threonine (instead of tyrosine). The bone morphogenetic protein straddles these two receptor serine-threonine receptor kinases, prompting the one called “Type II receptor” to add a phosphate group to its Type I receptor partner. Once activated, the Type I receptor kinase then phosphorylates a relay protein called “Smad.” Two Smads make a transcription factor; so the Smad decorated with phosphate by the receptor recruits a confederate—a different SMAD—and the two sashay into the nucleus, ready to translate the BMP message into changes in gene expression.

When Decapentaplegic and Dorsal are finished flipping genes on and off, the fly embryo has been partitioned into a series of compartments that run perpendicular to the compartments mapped out by the maternal effect genes and their successors. In the bottommost compartment, high concentrations of nuclear Dorsal have activated the genes twist and snail. Just a smidgen to the north, the concentra-

tion of Dorsal is no longer high enough to support snail expression; here only the Twist protein is produced. As Snail peters out and Dorsal declines, the rhomboid gene comes on. Finally, near the equator, Dorsal’s whisper activates the short gastrulation, or “sog.” For Decapentaplegic, running into the Sog compartment is like running into a brick wall—Sog hates the bone morphogenetic protein and silences it immediately. Cells able to hear Decapentaplegic give rise to the ectoderm of the fly’s back. But where the Decapentaplegic signal has been censored by Sog, cells elect a different fate: they become the fly’s nervous system. When the signal trading and gene tinkering are over, the embryo can stand back and admire the completed invisible anatomy of domains, each with a specific address defined by the intersection of anterior-posterior and dorsal-ventral gradients.

Meanwhile, subdivision of the dorsal-ventral axis has dovetailed with a dance in which the single layer of cells formed when the syncytium went cellular has shape shifted into three. Embryologists call this reel “gastrulation,” from “gastro,” meaning “gut.” Initiated when the cells representing the underside of the embryo—the cells that do the twist and snail routine in response to ear-splitting levels of Dorsal—draw together and roll inward to form a tube, gastrulation masterminds the all-important goal of differentiating inside and outside. In the process it introduces groups of cells eager to make new friends and carry on conversations, relationships that will be the takeoff point for the genesis of the nervous system, the musculature, and the internal organs.

OUTSIDE IN

It swims! It tumbles! It chases its prey! While the barely multicellular Volvox dog-paddles between sunny spots, Hydra, a minute relative of the jellyfish living in the same pond, flips and glides in pursuit of the one-celled organisms it calls dinner. Hydra can swim circles around its algal comrade because its ancestors upgraded their locomotor ap-

paratus, trading beating cilia for a new type of cell: muscle. Not that you’ll find red meaty muscles bulging under its skin. Hydra doesn’t have a skin; it’s just a pair of epithelial sheets, rolled up into a tube and crowned with a fringe of tentacles, and its muscle power doesn’t come from organized cohesive organs like our biceps but from primitive contractile cells, outfitted with elastic protein fibers able to contract and pump the animal along. These muscle-like cells are not even grouped together; they’re distributed randomly throughout the animal, both the outer epithelium, or ectoderm, and the inner layer, known as the endoderm.

Somewhere between the ancestors of Hydra and its kin and those of the flatworms—the next branch on the phylogenetic tree—evo-

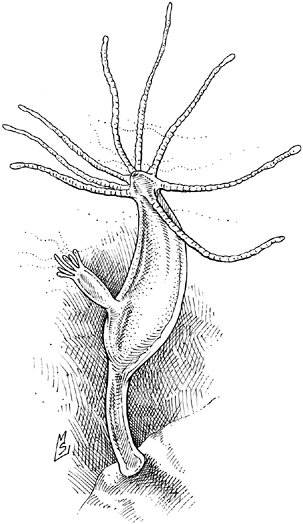

Hydra. The primitive contractile cells of this diploblastic (two-layered) organism prefigure the development of a third germ layer, the mesoderm, in larger animals.

lution took the muscle idea and expanded it into an entirely new family of tissues. This “mesoderm” (so named because it was sandwiched between the ectoderm and endoderm) gave rise not only to the musculature but also, as the metazoan lineage evolved, the digestive organs, the circulatory system, and the skeleton. An architectural innovation as significant as the post and lintel or the flying buttress, “the evolution of the mesoderm enabled greater mobility and larger bodies” and was a prelude to the evolution of such sophisticated features as a central body cavity, or coelem; a so-called through gut traversing the length of the organism; and appendages such as arms, legs, and wings.

The tripartite organization of larger metazoans is not easily appreciated in the adult, where it has been obscured by the intricacy of the mature internal anatomy but can be readily observed in the embryo—a fact that did not escape the notice of the nineteenth-century embryologists who spearheaded the acceptance of epigenesis. Indeed, the discovery of the three so-called germ layers was one of the strongest arguments in favor of progressive development, as each was found to give rise to a different set of tissues: the skin and nervous system from the ectoderm; muscles, bones, kidneys, heart, and blood from the mesoderm; and the lining of the gut, trachea, and lungs from the endoderm.

What’s more, nearly a century before Hans Spemann’s experiments with lens induction, Christian Pander, who discovered the germ layers, contemplated the possibility that the fates of the three layers might be interwoven, that “although already destined for different ends, all three influence each other collectively until each has reached an appropriate level.” Today, we know that the migration of cells and the determination of their identities that occur during the formation of the mesoderm—the central element in the dance of gastrulation—are indeed the result of intimate conversations. The induction of the mesoderm, the first steps in the construction of the head, the migration of cells, and the partitioning of the ectoderm into cells that will form skin and cells that will form brain are all

orchestrated by chemical signals exchanged between embryonic cells. Under the direction of these signals, “cells required for the formation of specific organs or body parts are physically brought together. Such juxtapositions of tissues, either transiently or permanently, facilitate inductive interactions that are critical for lineage specification and tissue patterning.”

After fertilization the amphibian egg cleaves to form a cluster of smaller cells, weighted at one end (the vegetal pole) by the bulky yolk that will nourish the growing embryo. Near the other end, the animal pole, adhesive contacts pull cells apart to create a small cavity, known as the blastocoel, creating space for the cells about to begin their great migration. Then, at a point just shy of the equator, the surface of the embryo dimples. This indentation—embryologists call it the “blastopore”—widens into a smile, a parting of the lips that invites nearby cells to explore the darkness within. Those cells—beginning with the adventurous individuals poised at the blastopore’s upper lip, dive eagerly into its maw, slide down its throat, slither along the roof of the blastocoel, and come to a stop at the far side. As they go, these adventurers pull the cells behind them down over the outer surface of the embryo like a stocking cap. In effect, the embryo swallows itself whole. The slipping and sliding transform the ball of cells into a hollowed-out plum, with the cells of the primordial endoderm lining the pit, those representing the immature ectoderm forming the skin, and, sandwiched between the two, the soft fruit of the future mesoderm, idling in anticipation of further instructions from the neighbors.

Contact with the embryonic optic vesicle could persuade cells undecided about their futures to devote themselves to forming the lens. Once they accepted the job of lens maker, however, cells lost the right to change their minds. Hans Spemann found that gastrulation was a time of equally momentous and irrevocable decisions. Cells started the dance of the germ layers open to suggestion—for example, a snippet of tissue transplanted from a region that would

normally become a tadpole’s nervous system to a region slated to become skin followed the example of its new neighbors and grew up to be skin instead of nerve:

The first experiment consisted in exchanging a portion of presumptive epidermis and neural plate between two embryos of the same age, each being at the beginning of gastrulation. The grafts took so smoothly and development proceeded so normally that their margins left no trace…. From this it was obvious that, as we expected, the portions were interchangeable.

Spemann and a student, Hilde Mangold, discovered one exception, however. Nerve and skin spent most of gastrulation deliberating before finally deciding on a fate and committing to it, but the precocious cells that formed the upper lip of the blastopore already knew what they wanted to be before the process even began:

It became apparent that a limited area, namely, the region of the upper and lateral blastopore lip did not conform. A portion of this kind, transplanted in an indifferent place in another embryo of the same age did not develop according to its new environment but rather persisted in the course previously entered upon and constrained its environment to follow it.

In one of the most celebrated experiments ever conducted by developmental biologists, Spemann and Mangold transplanted a piece of the dorsal blastopore lip taken from a newt embryo of a dark-colored species into the underside of an embryo of a light-colored species. But instead of switching gears and making belly skin (as ectoderm exposed to the optic vesicle responded by forming a lens), the blastopore transplant imposed its own agenda on its new neighbors. It ordered them to change direction, to put aside conventional ideas of becoming skin and take up the construction of a second backbone and spinal cord instead, setting in motion a sequence of events that culminated in the formation of a Siamese twin, joined

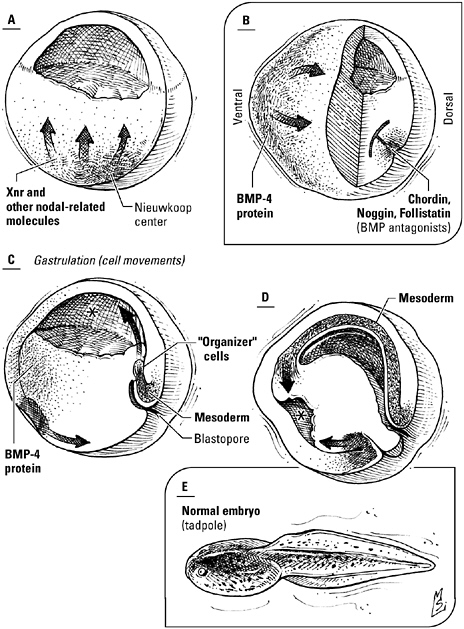

The induction of the mesoderm, the formation of the organizer, and the dance of gastrulation. A, Nodal-related proteins like Xnr, secreted by part of the primordial endoderm known as Nieuwkoop center, tell overlying cells to become mesoderm. Where concentrations of Xnr are highest—the dorsal lip of the blastopore—cells form a signaling center known as the organizer (B). The involution of the newly formed mesoderm, beginning with the cells of the organizer (C, D), segregates the three germ layers and establishes the dorsal-ventral and anterior-posterior axes, while the interaction of bone morphogenetic proteins, made by the ventral mesoderm, and BMP inhibitors, made by the organizer, differentiates the cells that will give rise to the nervous system from those that will give rise to the epidermis. E, the completed tadpole.

belly to belly with the host embryo. Because of their power to restructure the embryo, Spemann called the cells of the dorsal blastopore lip the “organizer.”

A benevolent dictator, the organizer never resorted to pushing cells around but won them over with compelling arguments. Spemann’s students Victor Twitty and M. C. Niu demonstrated that fluid drawn from a culture dish containing cells of the dorsal blastopore lip was as effective at duplicating embryos as the tissue itself, proof that the organizer’s authority resided in secreted chemical signals, not direct contact. In fact, researchers learned, the organizer itself is the product of earlier inductive interactions. The amphibian egg, it turns out, is talking from the moment it’s fertilized, conversations that not only lay the groundwork for the great migration of gastrulation but also determine the dorsal-ventral orientation of the embryo, the placement of the nervous system, and the boundaries of that all-important third germ layer, the mesoderm.

The frog embryo isn’t spoon-fed all the essentials of a floor plan like the fruit fly. Still, it is not dropped clueless into the pond. Dad offers the infant one hint: “dorsal” is the side opposite the point where the sperm pierces the egg. And Mother provides a second, in the form of mRNA encoding the gene regulatory protein β-catenin, essential confederate of transcription factors currently idling in the cell nucleus. But like Dorsal, β-catenin will never see the inside of the nucleus unless it receives explicit permission, in this case the transmembrane protein Dishevelled, implanted in vesicles sandwiched between the egg cortex—the band of cells lining the perimeter of the egg—and the yolk. Sperm entry releases microtubules stacked just under the surface of the egg’s plasma membrane like cordwood; down they slide, rotating the egg cortex so that the vesicles line up with the β-catenin protein on what fertilization has determined will be the dorsal side of the embryo. Now, Dishevelled can stabilize the transcription factor in this dorsal region, allowing β-catenin to accumulate to levels that can be heard by dorsalizing genes.

Meanwhile, under the influence of another transcription factor tucked into the egg by the mother frog, cells deep in the interior of the southern hemisphere—the primordial endoderm—establish radio station WXNR, broadcasting the same playlist around the clock: variations on the song “Xnr,” short for “Xenopus (the frog species most popular with biologists) Nodal-related” proteins. Members of the TGF-β family of signals that includes the bone morphogenetic proteins, Nodal proteins can be heard on the air in all developing vertebrate embryos; frog, fish, bird, or mammal, they send the same message: make mesoderm.

It’s easy to spot XNR’s loyal listeners. They’re the ones a little to the north, straddling the equator, particularly the cadre sitting on top of the blastopore, articulate types that entertain fond memories of Hans Spemann. Under the combined influence of stadium concert volume Xnrs and the dorsalizing influence of β-catenin, they not only agree to be mesoderm—specifically, dorsal mesoderm—but also volunteer for the all-important job of organizer. Their neighbors to either side appreciate XNR as well, although they don’t have it playing at the same volume and they don’t enjoy the simultaneous benefits of exposure to β-catenin. Still, listening to a Nodal protein is enough to convert them into lateral mesoderm, responsible for the heart, blood, blood vessels, and limbs (both naturally occurring and experimentally induced). On the side of the embryo opposite the organizer, however, XNR reception is so poor it’s barely audible. Cells here listen carefully and take the mesoderm message to heart but interpret it their own way; they become ventral mesoderm.

As gastrulation gets under way, cells appointed to the mesoderm by Nodal signaling proteins begin to dive into the blastopore and slide along the roof of the egg, beginning with those that will form the head structures. Next come the cells responsible for the connective tissues—bone, muscle, and cartilage—of the back, followed by heart and kidney mesoderm. Bringing up the rear are the cells of the ventral mesoderm. Following in their wake, the cells of the future ectoderm wrap themselves around the surface of the embryo, swad-

dling the outer surface of the embryo in tissue that will form skin and nervous system.

Every cell in that ectoderm wants to be a neuron. And theoretically it could, for that’s the default condition, the path an ectodermal cell is slated to follow at this point unless it’s told otherwise. Unfortunately, some must take the less glamorous job of skin. The ventral mesoderm, assigned the thankless job of posting the bad news, heaves buckets of the bone morphogenetic proteins BMP4 and BMP2, synonyms for “ventral” and “skin,” at the ectoderm. But if everyone changes course and follows these instructions, the embryo will be all belly skin and no brain. It’s up to the organizer to temper the situation, issuing antagonist proteins that intercept the BMPs and negate them. “Chordin!” it yells. Or “Noggin!” Or “follistatin!” Cells exposed to the highest concentration of these molecules ignore the BMP message and follow the default program, remaining dorsal and becoming neural. Cells farther from the organizer, exposed to plenty of BMP signals but little of the antagonists, form epidermis. Collectively, the intersecting gradients of BMPs and organizer antagonists partition the ectoderm, carving out one territory to be the nervous system and the other to be the skin that protects it and other underlying structures from the elements.

Creatures like birds and mammals also turn outside in during embryonic development but have altered the vertebrate developmental program exemplified by the frog to accommodate changes to the basic body plan as well as the evolution of extra-embryonic tissues of the placenta. In the chick, for example, the embryo, cramped into the limited space between the hard eggshell and the massive yolk, begins as a disc of cells, the blastoderm, instead of a ball. Selected cells of the mammalian embryo secede early in development to form the placental tissues; the embryo itself is cup or disc shaped. Cells of both migrate into the interior of the embryo through a groove known as the primitive streak, rather than a blastopore—but both still feature signaling centers that control the formation and patterning of the germ layers.

What’s more, put your ear to a hen’s egg or a mother mouse’s belly and you’ll hear familiar commands directing traffic. “Step back, please,” calls β-catenin, and you know that this will be the dorsal side of a chick embryo. Nodal proteins still induce the mesoderm. Where high levels of Nodal and β-catenin coincide, an organizing center, known as Henson’s node in birds and simply “the node” in mammals, forms and secretes signals antagonistic to bone morphogenetic proteins—a contest that still figures prominently in the decision to become neural ectoderm or epidermal ectoderm.

To the chorus of signaling molecules belting out mesoderm and migration, these embryos have added another: the voice of FGF, harmonizing with Nodal proteins, BMPs, and BMP antagonists. In the early embryo, FGF joins the call for the induction of the mesoderm. Later in development, the meaning of the FGF signal changes, from “make mesoderm” to “make nervous system.” Secreted by precursors of cells that form Henson’s node—the avian equivalent of the amphibian organizer—FGF “primes” cells of the chick embryo to respond more enthusiastically to the proneural, anti-BMP messages that will follow.

According to Lewis Wolpert, “The most important event of your life is not birth or marriage, but gastrulation”—a milestone you share with frogs and fish, the chick and the mouse. The prelude to this dance is the appointment of cells to the mesoderm; its climax, the sorting and shifting of these cells and their compatriots to form the three germ layers. Along the way, the order of migration and the interactions between signals, particularly the bone morphogenetic proteins and their antagonists, have also patterned the anterior-posterior and dorsal-ventral axes and sketched the location of the nervous system. Choreographed by signaling molecules conserved across species, the balletic movements of gastrulation, coupled with the events of earlier development, culminate in the solution of problems that confront all vertebrates and, indeed, all animals: the establishment of polarity, the isolation of an internal milieu, and the genera-

tion of an invisible grid of compartments in preparation for the next stage of development.

AN ARM AND A LEG (AND A BACK AND A BRAIN)

The foundation has been poured, the walls erected, the roof shingled. But it will take more than two-by-fours to make this skeleton of a house a home. Windows and doors must be hung. The future kitchen, bathrooms, and laundry room must be plumbed. The new owners will surely want to move around, cook, read, supervise homework, or find their kids after dark, so an electrician is in order. Someone had better grade that hillock of dirt out front, and someone else had better turn that floodplain of mud into a driveway. And that’s not even counting all of the amenities—carpets, appliances, fixtures, tile—still to be installed.

The embryo’s construction project has also made considerable progress. Signaling pathways and teams of transcription factors have decided which end will lead and which will follow as well as which side will face the sky and which the ground, assigned cells to germ layers, rearranged cells to seal off the interior of the organism from the outside world and facilitate the further exchange of chemical signals, and divided the embryo into a system of compartments, each characterized by a unique pattern of gene expression. Now these compartments can begin to interact to refine positional information, shape organs, put the finishing touches on the body, and drive the final differentiation of cells and tissues. “The initial structure is the basis for further subdividing the organism into smaller and smaller domains,” explains Marc Kirschner. “Once an embryo has mapped out the initial spatial pattern of compartments, cells within the domains can further differentiate in a variety of ways. For example, those domains can interact with neighboring domains. And as a result of those interactions, you can end up with cells that are now different because they were close to a different domain.”

In a typical vertebrate embryo, for example, the molecular

machinations of early development have defined, along the longitudinal axis, the rough outline of the torso. The embryo has a top and a bottom; clearly, the future limbs go somewhere in the middle. But while there’s a space to put an arm or a leg, it’s impossible to make out even the slightest bulge of an emerging limb bud, much less a fully jointed limb complete from shoulder to fingers or hip to toes. The mesoderm is just a layer of cells; actual bones and muscles are still in the planning stages. And the cellular territory labeled “neural ectoderm” by FGF and BMP antagonists like Chordin and Noggin doesn’t constitute a functioning nervous system any more than a stack of bricks and a pail of mortar constitute a finished wall.

The developing embryo meets the challenge of later embryonic development the same way it met earlier challenges: by talking itself along toward maturity, linking signals to transcription factors that continue the task of “compartmentalizing” the genome, as Kirschner calls it. Of course, more compartments—and more interactions between compartments—demand precise, effective communication. Some tasks will require new words and novel variations on the basic syntax of cellular communication. But familiar words and tried-and-true mechanisms, such as the morphogen gradient, can also be used in new ways; indeed, the parsimonious nature of evolution encourages such recycling. “Setting up a graded positional cue is unlikely to be simple,” according to Miriam Osterfield, Marc Kirschner, and John Flanagan, in a 2003 review published in the journal Cell. Given the time and effort needed to elaborate the morphogens themselves, the components of their signal transduction pathways, and mechanisms to control signal secretion, deposition, and action, “it is not surprising that evolution, having set up a successful gradient system … would exploit it for multiple purposes.” Hedgehog, the signaling protein that meant “posterior” in the fruit fly during the definition of the parasegment boundary, is a good example. Swap an amino acid here and there to put a vertebrate stamp on it, give it a new definition: “motor neuron” and you can use it to turn a sheet of ectoderm into the beginning of a central nervous system.

“What we actually know about Hedgehog is provocative, even if it’s not definitive,” says molecular biologist Philip Beachy. “To begin with, the signal is made in an interesting way.” Beachy explains that Hedgehog (actually, Hedgehogs, for vertebrates like us make three different varieties of Hedgehog protein: Desert hedgehog, Indian hedgehog, and Sonic hedgehog), like many other proteins, begins life as part of a larger precursor. But while the others depend on a separate protein-trimming enzyme, or protease, to liberate them, the Hedgehog precursor does the job itself. Even more curious, the knife it uses bears an uncanny resemblance to a type of protein domain more typical of bacteria. Known as an “intein,” it “carries out a splicing operation. The intein excises itself, then rejoins the two bits of the ‘host’ protein,” says Beachy. Then again, Hedgehog seems to collect heirlooms: another segment of the protein can be superimposed on a common bacterial cell wall enzyme. Hedgehog, in other words, may be a chimera, two prokaryotic enzymes fused into a single eukaryotic signaling protein. “What sort of organism this happened in or what pathway it took from primitive unicellular organism to patterned multicellularity, we don’t know,” Beachy notes. What’s important, he adds, is that the journey culminated in a protein with a topography that “is useful for binding.”

Then there’s Hedgehog’s choice of fashion accessories. It’s not unusual for eukaryotic proteins to don bits of frippery during the final stages of synthesis, typically sugar groups thought to expedite folding or discourage assaults by proteases. Hedgehog, however, believes that sugars are so last millennium. Its jewelry is made of lipids: the fatty acid palmitate and a molecule of cholesterol. Now decorating yourself with lipid might be creative, but that’s just not the way it’s done in the Fraternal Brotherhood of Secreted Proteins. Biological membranes, you’ll remember, are principally lipid themselves. A lipid-decorated molecule, therefore, is more likely to be trapped in the membrane than to be secreted. With the spare tire it’s sporting, Hedgehog ought to be about as mobile as a sumo wrestler. Instead, it’s gotten around the problem with its own personal taxi service. A

receptor-like protein, Dispatched, binds and escorts Hedgehog out of the cell, then inches along a path of sticky, sugar-coated proteins embedded in the extracellular matrix to place the signal exactly where it’s needed. “The regulation of Hedgehog movement is so important it requires a dedicated component just to release the signal,” Beachy says. “You can think of cholesterol as the ‘handle’ that directs Hedgehog to this movement machinery. It doesn’t so much restrict [Hedgehog’s] motion as facilitate its regulation.”

Finally, Hedgehog’s grammar would have your high school English teacher reaching for her red pencil. Every Hedgehog sentence contains a double negative: the signal itself is a synonym for “no,” and so is its receptor, Patched. Blame the arrangement on the chatterbox heading the signal transduction relay, a second transmembrane protein, Smoothened, which shadows the Patched receptor much as a remora shadows a shark. Smoothened loves to talk; left to its own devices, it would have the pathway’s target genes on every hour of every day. And since that would encourage not only some odd developmental decisions but uncontrolled cell division as well, Smoothened needs to be hushed unless there’s a legitimate reason for it to be active, a job that falls to Patched. In the absence of Hedgehog, the receptor whispers “No talking!” and enzymes farther down the pathway lop a bit off the transcription factor known as “Ci” (in flies, for “Cubitus interruptus”) or “Gli-1, -2, or -3” (in vertebrates, for “glioblastoma,” a kind of brain cancer), turning it into a gene repressor rather than a gene activator. When Hedgehog says “no” to Patched, Smoothened can tell the enzymes to leave the transcription factor alone; in its intact form, it can now turn genes on.

The double negative is there for a reason: it forces cells to stop, look, and listen before making a life-or-death decision. As Beachy points out, even after Hedgehog has shut Patched down, gene expression doesn’t flip from off to on immediately. “The repressor [that’s already present] must be degraded, over a period of hours, before you have full activation,” he says; as a consequence, “you have a built-in time delay in the circuit.” He speculates that this lag be-

tween pathway activation and gene activation may ensure a critical level of precision. “In these pathways you have a longer timeframe. Precision is more important than speed. You don’t want to be set up on a hair-trigger; you want to take the time to get it right, because it has such critical implications for the development and life of the organism. Make a mistake and you could end up with the wrong pattern.”

If there’s one place where a vertebrate embryo certainly doesn’t want to end up with the wrong pattern, it’s in the developing central nervous system.

Growing up is never simple. But perhaps no tissue faces a more daunting challenge than the nervous system. Beginning only with the dorsal ectoderm rescued from a life as skin by the antagonists of the organizer, the vertebrate embryo must shape a brain at the head end and run a spinal cord down the back. It must tell some cells to be informatics specialists—neurons—and others how to become the glial cells that insulate nerve fibers and assist the neurons in their work. What’s more, the decision making doesn’t stop here. A cell that has elected to be a neuron must still decide what sort of neuron—perhaps a squat, bushy Purkinje cell in the cerebellum, a willowy pyramidal cell in the cerebral cortex, or an interneuron shuttling messages over short distances—and it must be grouped with similar neurons to form collectives. Finally, the peculiar demands of information processing have made neurons very choosy about who they’ll talk to. Each must thread its axon, the fiber it will use to talk, precisely through the amorphous darkness to its appointed partner—even if that partner is located on the other side of the brain.

Thanks to the organizer’s zealous propagandizing, cells of the dorsal ectoderm have bought into the neural agenda. Now they will grow tall, into a layer of long, thin cells known as the neural plate. Pushed by the epidermis on either side, the neural plate hunches up and begins to fold in half along the midline like a book. The longer the epidermis shoves, the higher and closer the edges of the plate

grow, until they meet and merge, overrun by future skin. Fluid trapped in the anterior end strains at the walls of the tube and causes them to balloon outward in three places, forming the so-called primary brain vesicles. As neural development proceeds, two of these vesicles will be squeezed in the middle to create a total of five bulges at the anterior end of the neural tube corresponding to the five major divisions of the brain: telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon, metencephalon, and medulla.

The posterior portion of the neural tube will become the spinal cord. This part of the nervous system is home to the motor neurons that command the muscles; the way station where incoming axons of the sensory neurons, transmitting information from skin receptors mediating touch and pain, contact neurons charged with relaying the data to sensory processing centers in the brain; and the work space of a multitude of interneurons, cells that ferry information from neuron to neuron rather than from sense organ to neuron or neuron to muscle. In the mature spinal cord, these neuronal elements form a central core, the gray matter, embedded in a cocoon of insulated fibers—the so-called white matter—traversing the cord’s longitudinal axis. Viewed in cross section, the gray matter stretches out in a butterfly-shaped formation splayed across the midline: motor neurons in the so-called ventral horn (the lower wings of the butterfly), incoming terminals and sensory relay neurons in the dorsal horn (the upper wings), interneurons concentrated in the deeper layers near the center. Here in the embryo, however, the future spinal cord languishes in shapeless anticipation, while the ectoderm overhead and the mesoderm below—specifically, the notochord, a temporary stand-in for the backbone while it’s under construction—contest for the hearts and minds of immature cells.

If you detect something familiar about the notochord, you’re not imagining things; the cells of this structure are descendents of the organizer, all grown up and done with baby talk. Now their vocabulary consists of the words “Sonic hedgehog,” which they chant ceaselessly at the base of the neural tube. Cells that listen to Sonic

hedgehog and take its message to heart become the floor plate and begin to chant “Sonic hedgehog” themselves. Their signal diffuses out of the floor plate and generates a gradient, pointing in a ventral-to-dorsal direction.

At the same time, the epidermis above the neural tube is also talking. It spews a cocktail of signaling molecules belonging to the TGF-β “superfamily,” in particular the bone morphogenetic proteins BMP4 and BMP7. These signals coax cells at the top of the neural tube into becoming the roof plate and setting up their own signaling center. Roof plate TGF-β signals diffuse out of the plate region and create a second gradient, pointing in the dorsal-to-ventral direction, a mirror image of the gradient formed by Sonic hedgehog.

Depending on where they are located, cells of the neural tube are exposed to varying amounts of Sonic hedgehog and TGF-β-type signals and base their decisions on what to do next accordingly. Cells near the roof plate, where TGF-β signaling predominates, turn on transcription factors that start them down the road to becoming interneurons. Those just north of the floor plate pay more attention to Sonic hedgehog. They activate transcription factors able to help them become motor neurons eager to learn which muscle group they are to innervate—perhaps, in a hypothetical world, the muscles of your third arm.

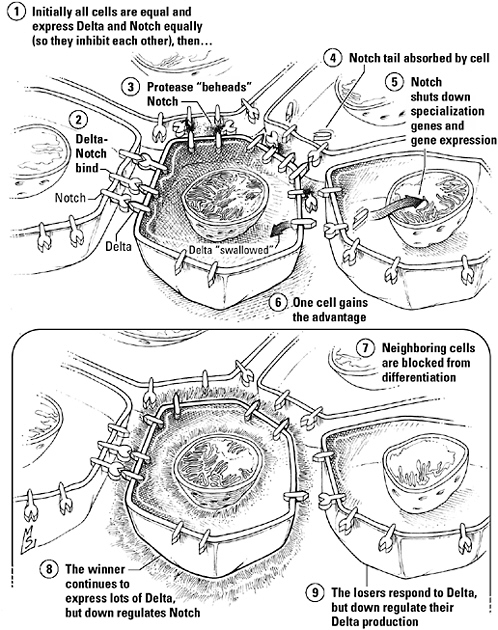

Cells can be neither motor neurons nor interneurons, however, unless they’ve committed irrevocably to the neuronal program. Membership in the neuroectoderm is a job interview, not an employment contract; to secure a permanent position in the company of neurons, a cell must first face off against any number of equally qualified neighbors. “Contingency plans are part and parcel of development,” writes developmental biologist Eric Lai. “Often, more cells than necessary have the opportunity to become a specialized cell type, a scheme that allows for backups.” But when all applicants look the same and express the same genes, how is a little embryo to decide who ought to get the job? Fortunately, cells can resolve this

issue themselves, calling up a novel signaling mechanism evolved specifically for conducting one-on-one conversations and consisting of just two words: “Notch” and “Delta.”

“Unlike other signaling pathways, which are activated by factors made elsewhere in the embryo, Notch signaling takes place right between cells,” says molecular biologist Gerry Weinmaster, an intimacy necessitated by Delta’s agoraphobia. She explains that while hormones sail the bloodstream, growth factors diffuse, and Hedgehog takes a taxi, the Delta signal stays rooted firmly in the membrane of the cell that made it, daring to expose only its head and shoulders. Notch, the receptor, is also embedded in the membrane. In order for Notch to bind Delta, therefore, the cell bearing the receptor and the cell sending the signal must be close enough to touch.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise, then, that both cells participate in the signaling process. The Notch receptor doubles as this pathway’s transducer, but before it can put on its transduction hat, it has to escape from the membrane. That’s where the Delta-bearing cell steps in to help. As soon as Notch binds Delta, the receptor stretches its neck out so that a nearby protease can behead it; the signaling cell then swallows both the signal and binding site fragment of the receptor (to which it’s still attached) in one gulp. With that mess out of the way, a second protease can swoop in and amputate Notch’s tail. This disembodied free end is the pathway’s only intracellular signaling protein, and it hikes itself off to the nucleus to negotiate the exchange of transcription factors regulating so-called proneural genes. Whispers are followed by the muffled sound of the genes being wrapped for storage. No use pining—this cell’s application to be a neuron has just been denied.

Notch and Delta’s best-known accomplishment is the sensory bristle of the fruit fly, the arthropod equivalent of the touch receptors in our skin. Each bristle is actually a cluster of four cells—a neuron, the sheath cell surrounding it, a socket cell, and a shaft cell,

Lateral inhibition mediated by Notch-Delta signaling. Cells vying to become neurons begin as equals. At this initial stage, all express the membrane-bound signal, Delta, and its receptor, Notch; as a consequence, each inhibits its neighbors but is also inhibited by them. A lucky break gives one cell an advantage; as a result, it can suppress the so-called proneural genes of those in the immediate vicinity even more effectively, while downplaying its own sensitivity to the Delta they express, weakening any attempt to retaliate.

all descendents of a single sensory mother cell, winner of a competition between two to three dozen identical prospects. At the start of this contest, all the cells of this “equivalence group” express similar levels of both Delta and Notch; each, as a consequence, blocks the differentiation of its neighbors but is blocked by them in return. Development is locked in a stalemate—until one cell loses count and finds itself with a few extra Delta molecules, allowing it to talk just a little louder than those around it. This cell can now suppress its neighbors more effectively—including their expression of Delta—and tone down its own Notch receptors in the process, so it can evade their retaliation. As a consequence, the noisy cell gains the upper hand, while those surrounding it sink lower and lower into repression. Their proneural genes are turned off, and the loudmouth becomes the mother cell.